Difference between revisions of "Tibetan medicine in Buryatia"

(Created page with " {{Wiki|Folk}} medicine of the {{Wiki|Mongolian}} people as a legacy of their traditional {{Wiki|culture}} is traced back to deep antiquity. Most likely, the...") |

|||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| + | <nomobile>{{DisplayImages|2424|2443|2089|2893|4316|3119|205|3867|1578|1474|135|3072|3804|2668|3608}}</nomobile> | ||

| Line 5: | Line 6: | ||

| + | {{Wiki|Folk}} [[medicine]] of the {{Wiki|Mongolian}} [[people]] as a legacy of their [[traditional]] {{Wiki|culture}} is traced back to deep antiquity. | ||

| − | + | Most likely, the [[healing]] [[art]] of the [[nomadic]] peoples is first referred to in the {{Wiki|Chinese}} treatise “Nei [[Ching]]” of the third century B. C. It says: “In the [[north]] there lies a remote, lonely and almost inaccessible country. | |

| − | + | The [[air]] is very cold there. Its dwellers keep herds of livestock and feed on dairy products. They [[suffer]] mostly from cold disorders, treated with cauterization. Thus, cauterization has emerged from the [[north]]” (See 40, p.5). | |

| − | According to the {{Wiki|data}} from the “{{Wiki|Encyclopedic}} | + | From the sixteenth century onwards, the [[Tibetan]] branch of [[Buddhism]] of the [[gelugpa sect]] had been spreading throughout [[Mongolia]]. |

| + | |||

| + | The Danjur comprising larger treatises on [[Ayurvedic medicine]] as well as the [[rGyud bzhi]] (The [[Four Tantras]]) (30, 31) and other {{Wiki|medical}} texts were translated into {{Wiki|Mongolian}}. | ||

| + | |||

| + | {{Wiki|Medical}} {{Wiki|colleges}}, similar to [[Tibetan]] [[sman-pa datsan]], were opened at [[monastic]] centers. | ||

| + | |||

| + | As a result of many-year experiment on the {{Wiki|medicinal}} arsenal used by {{Wiki|Mongolian}} practitioners of [[traditional]] [[medicine]], imported raw material was supplanted by local substitutes. | ||

| + | |||

| + | According to the {{Wiki|data}} from the “{{Wiki|Encyclopedic}} Dictionary of {{Wiki|Chinese Medicine}}”, in contemporary Inner Mongolia ([[China]]) 50% of raw material is of local origin, about | ||

40% is brought from the {{Wiki|Chinese}} provinces {{Wiki|Yunnan}}, Xi — chuan, Guandung, Kuku-nor, Xinjan, and [[Tibet]], and around | 40% is brought from the {{Wiki|Chinese}} provinces {{Wiki|Yunnan}}, Xi — chuan, Guandung, Kuku-nor, Xinjan, and [[Tibet]], and around | ||

| Line 16: | Line 26: | ||

10% only is imported from [[India]], Tailand, and {{Wiki|Malaysia}} | 10% only is imported from [[India]], Tailand, and {{Wiki|Malaysia}} | ||

| − | (40, p. 12). The authors of the {{Wiki|monograph}} “[[Plants]] of | + | (40, p. 12). The authors of the {{Wiki|monograph}} “[[Plants]] of Tibetan [[Medicine]]” believe that [[plants]] of local origin in [[Mongolian]] [[medicine]] make 57%, [[Tibetan]] and [[Indian]] ones 11.6% and 11.25% correspondingly, and {{Wiki|Chinese}} ones 9.56% (27, p.92). |

| + | |||

| + | While estimating the {{Wiki|data}}, one has to take into ac — count that {{Wiki|Chinese}} authors are confined within the boundaries of [[Inner Mongolia]] only, without considering the flora of the more northern Peoples’ {{Wiki|Republic}} of [[Mongolia]] and [[Buryatia]]. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Upwards along the meridian, naturally, the percentage of southern {{Wiki|species}} {{Wiki|diminishes}}, what is convincingly illustrated by the {{Wiki|medicinal}} assortment used by [[Buryat]] healers. | ||

| − | + | [[Zabaikalye]] flora accounts for 85.06%, [[Indian]] {{Wiki|species}} | |

| − | |||

| − | + | 3.64%, and [[Tibetan]] ones 3.46% (27, p.92). {{Wiki|Data}} of the ethnofloral analysis of the "{{Wiki|medicinal}} flora" allow the authors of the “[[Plants]] of [[Tibetan Medicine]]” to come to a conclusion about [[uniqueness]] of the three “[[strands]]” of [[Tibetan medicine]] under study – [[Tibetan]] proper, {{Wiki|Mongolian}} and [[Buryat]]. | |

| − | + | Only the {{Wiki|principles}} of treatment, [[perception]] of [[unhealthy]] [[body]], specifics of administering remedies, and others were ob — viously common for them. The {{Wiki|medicinal}} means assortment was sharply different and was most likely created de novo so far [[traditional]] [[medicine]] of [[Tibet]] was penetrating into the ad — jacent countries (27, p.93). | |

| − | + | According to [[Buryat]] historical chronicles, the [[Khori]] and [[Selenga]] [[Buryat]] tribes gravitated to [[Zabaikalye]] in the late sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries, having converted to [[Buddhism]]. | |

| − | + | The introduction of [[Tibetan medicine]] among the [[Buryats]] is related by these chronicles with the date of the official adoption of [[Lamaism]] as a [[state religion]] of the {{Wiki|Mongols}} in 1576. | |

| − | + | Since the last quarter of the seventeenth century, several travelers either with diplomatic or [[scientific]] purposes passed through the [[Buryat]] lands, among them [[Nikolai Spafary (1675), Izbrant Ides (1693), Lorents Lange | |

(1716), Johan Georg Gmelin (1735), Piotr Simon Pallas | (1716), Johan Georg Gmelin (1735), Piotr Simon Pallas | ||

| − | (1772) and others, who recorded valuable [[information]] in their diaries and reports regarding {{Wiki|economy}}, household and [[habits]] of the [[Buryats]]. But, no [[doubt]], Johan-Georg | + | (1772) and others, who recorded valuable [[information]] in their diaries and reports regarding {{Wiki|economy}}, household and [[habits]] of the [[Buryats]]. But, no [[doubt]], Johan-Georg Gmelin was the pioneer to describe [[Tibetan medicine]] in Zabaikalye. |

| + | |||

| + | Crossing Zabaikalye in 1735, on the Onon-river he encountered a lama-healer; the [[latter]] showed him his [[own]] treatises, {{Wiki|medicines}}, and instruments and demonstrated some techniques of preparing {{Wiki|medicines}} and therapies. | ||

| − | + | According to Gmelin, this [[lama]] practiced bloodletting, moxabustion, applied cupping-glasses, and owned a significant set of surgical instruments. It was noted, that he was reckoned locally a “superb” oculist. | |

| − | + | Noteworthy, Gmelin’s descriptions of [[Tibetan]] medicine among the [[Buryats]] almost coincides in time with the first reports on this [[medicine]] by Dominican Ippolit Dezideri who visited [[Lhasa]] in 1716 and stayed there several years, and by doctor Saunders accompanying the [[British]] Embassy to [[Tibet]] in 1783 (30, p. 2). | |

| − | + | The [[Buryat]] {{Wiki|clergy}} had widely used the medicine for strengthening its [[own]] influence and attempted to assemble lamas-healers in [[monasteries]]. It is known that Agvan-Puntsok, [[Tibetan]] by origin, the leading [[lama]] of the day in [[Buryatia]], was highly esteemed as a [[physician]]. And the first [[physician]] among the [[Buryats]] was Zhimba Akhaldayev who went in 1721 for {{Wiki|training}} to [[Mongolia]], and then to [[Tibet]]. According to one of poorly known chronicles, he was a “prominent healer and a man of [[fortune]]” (48 p.69). It was he who established the first [[datsan]] in Gusinoozersk in | |

| − | [[ | + | 1741. After Akhaldayev, Damba-Dorji Zayayev was educated in [[Tibet]]; he also became a known healer (48, p.57). |

| − | + | [[Tibetan medicine]] was extensively practiced in Zabaikalye in the eighteenth century; this was reflected in special articles of the so-called “Common Code of [[Buryats]]”. | |

| − | The new stage of the [[Tibetan medicine]] [[development]] in Zabaikalye was the official establishment of {{Wiki|medical}} | + | The new stage of the [[Tibetan medicine]] [[development]] in Zabaikalye was the official establishment of {{Wiki|medical}} colleges – [[smanba datsans]] in [[monasteries]]. |

| − | + | In 1869 the school of [[Tibetan medicine]] was opened at the [[Tsugol datsan]]. | |

| − | + | Soon, similar establishments were appended to other [[datsans]], like [[Aginsky]], [[Egitui]], [[Atsagat]], [[Tugnugaltai]], [[Jida]], [[Yangazhin]], [[Kyren]], and others. | |

| − | 4.6% from the total number of [[lamas]]. Figures for 1923 | + | Training at the {{Wiki|medical}} {{Wiki|colleges}} was modeled after the [[smanba datsan]] [[traditions]] of [[Lavran monastery]] at [[Amdo]] ([[Tibet]]). |

| + | |||

| + | The courses lasted five years, and [[disciples]] were expected to memorize the canonic classics of [[Tibetan]] medicine [[rGyud bzhi]], to familiarize with its commentaries, formulas, and to become able of compounding remedies. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The title [[smanramba]] was conferred upon these [[disciples]] who completed the five year course (29, p. 63-64). | ||

| + | |||

| + | The number of [[disciples]] at the largest school of [[Tibetan medicine]] at the [[Atsagat datsan]] reached 50-60 (29). | ||

| + | |||

| + | According to the approximate {{Wiki|data}}, by the end of the nineteenth century in Zabaikalye lamas-physicians totaled 700 whereas the overall numbers of [[lamas]] by the {{Wiki|First World War}} had risen to about 15 thousand (31, p. 15). Thus, their correlation was | ||

| + | |||

| + | 4.6% from the total number of [[lamas]]. Figures for 1923 specify the same proportion: the number of [[lamas]] decreased to | ||

9134 (31, p.151), among whom about 500 continued their | 9134 (31, p.151), among whom about 500 continued their | ||

| Line 60: | Line 85: | ||

For the entire period of [[Tibetan medicine]] [[existing]] in | For the entire period of [[Tibetan medicine]] [[existing]] in | ||

| − | [[Buryatia]], local [[datsans]] printed about 20 most significant {{Wiki|theoretical}} and {{Wiki|practical}} manuals on [[Tibetan medicine]] in the [[Tibetan]] and {{Wiki|Mongolian}} [[languages]]. By its value, the | + | [[Buryatia]], local [[datsans]] printed about 20 most significant {{Wiki|theoretical}} and {{Wiki|practical}} manuals on [[Tibetan medicine]] in the [[Tibetan]] and {{Wiki|Mongolian}} [[languages]]. By its value, the [[Vaidurya-sngonpo]] is the most impressive [[xylograph]] [[printing]], comprising 1284 folios of an average format. |

| − | After the October {{Wiki|Revolution}} of 1917 efforts were made to reorganize the [[datsan]] {{Wiki|medical}} {{Wiki|colleges}} into | + | After the October {{Wiki|Revolution}} of 1917 efforts were made to reorganize the [[datsan]] {{Wiki|medical}} {{Wiki|colleges}} into “secular” schools for [[laymen]] and [[monks]] and to introduce classes in {{Wiki|anatomy}}, [[physiology]], diagnostics of {{Wiki|diseases}} according to [[western]] [[scientific]] [[medicine]]” (31, p.7l). In 1924 under the supervision of Prof. [[G. Tsybikov]], famous for his trip to Ti — |

| − | bet, there was established the [[Center]] of [[Tibetan medicine]] and the first school of a new type opened at the [[Atsagat datsan]]. In the early 40s the [[Center]] was closed, and the la — mas underwent repressions. As a result of the elimination of the [[Buryat]] {{Wiki|clergy}} as the estate, [[Tibetan medicine]] was neglected and forgotten in [[Buryatia]] for many years. | + | bet, there was established the [[Center]] of [[Tibetan medicine]] and the first school of a new type opened at the [[Atsagat datsan]]. In the early 40s the [[Center]] was closed, and the la — mas underwent repressions. |

| + | |||

| + | As a result of the elimination of the [[Buryat]] {{Wiki|clergy}} as the estate, [[Tibetan medicine]] was neglected and forgotten in [[Buryatia]] for many years. | ||

However, the “dark period” in the history of [[Tibetan medicine]] in [[Buryatia]] did not result in the complete loss of this important constituent of the [[traditional]] {{Wiki|culture}}. In | However, the “dark period” in the history of [[Tibetan medicine]] in [[Buryatia]] did not result in the complete loss of this important constituent of the [[traditional]] {{Wiki|culture}}. In | ||

| Line 70: | Line 97: | ||

1968 a group of research fellows of the [[Buryat]] [[scientific]] | 1968 a group of research fellows of the [[Buryat]] [[scientific]] | ||

| − | center was commissioned [[scientific]] research on the theme “Description of [[healing]] properties of {{Wiki|medicinal}} means of [[Tibetan medicine]]” | + | center was commissioned [[scientific]] research on the theme “Description of [[healing]] properties of {{Wiki|medicinal}} means of [[Tibetan medicine]]”. |

| − | + | Since that time, regular studies in the field of [[Tibetan medicine]] in [[Russia]] have been carried out aimed towards introduction of its many-century positive [[experience]] and expertise into practice of {{Wiki|modern}} public [[health]] care. | |

| − | + | Further, on the basis of this group, there was organised the laboratory of physiologically active substances, and in 1975 the Department of [[Tibetan medicine]] established. Since the very beginning, practitioners of Tibetan [[medicine]] were involved in research programs of the Department. | |

| − | + | Nowadays the Department of [[Tibetan Medicine]] of the [[Buryat]] Institute of {{Wiki|Biology}} under {{Wiki|Siberian}} [[Division]] of the {{Wiki|Russian Academy of Sciences}} is divided into the laboratory of chemical and {{Wiki|pharmaceutical}} studies, the laboratory of experimental {{Wiki|pharmacology}} and pharmacotherapy, | |

| − | + | the laboratory of {{Wiki|toxicology}} of {{Wiki|medicinal}} means, and one minor sector of [[information]] supply, all staffed with forty-three researchers, [[including]] three researchers with {{Wiki|doctorate}} degrees and nineteen candidates of {{Wiki|sciences}}. Internship on profile [[disciplines]] is also [[offered]]. | |

| − | + | The [[staff]] has accomplished several [[scientific]] and research themes, [[including]] the [[development]] on applied problems. | |

| − | + | {{Wiki|theoretical}} aspect, is the [[development]] of recommendations on the {{Wiki|principles}} of translation and [[adaptation]] of [[ancient]] {{Wiki|medical}} [[manuscripts]]. | |

| − | + | Within the series of the “[[Tibetan Medical Literature]]”, the [[Atlas of Tibetan Medicine]], the complete version of the canonic treatise [[rGyud-bzhi]], the [[Kun gsal nan zod]], and the [[mNgon mtshar dg’a ston]] were translated into {{Wiki|Russian}} and published. {{Wiki|Monographs}} on discrete treatises and [[sections]] of [[Tibetan medicine]], numerous collected [[scientific]] articles and abstracts, {{Wiki|bibliographical}} catalogues, preprints, and newsletters have been published. | |

| − | + | In the {{Wiki|practical}} aspect, the most substantial results are: the [[elaboration]] of methods of identifying names of medicinal raw material; selection of potentially useful formulas, methods of deciphering and interpreting names of diseases; the patented methods of simulating {{Wiki|diseases}} of the {{Wiki|stomach}} and gall-bladder based on new {{Wiki|data}}. | |

| − | + | The methods for obtaining thirty-nine new means and {{Wiki|substances}}, which possess higher {{Wiki|pharmacological}} value as compared to analogues, have been patented; forty-nine kinds of thans (fine ly powdered compounds) have been worked out and introduced into practice. | |

| − | + | Research will be continued in these three [[directions]]: source studies, translation and publication of [[Tibetan]] medical works; creation and introduction of new highly effective preparations based on [[Tibetan]] sources; approbation and introduction of [[rational]] methods and technologies of treatment and prophylaxis of widely-spread {{Wiki|diseases}} (35, p. | |

| − | + | 163-167). | |

| − | + | The theme of {{Wiki|folk}} [[medicine]] in the context of [[Buryat]] [[traditional]] {{Wiki|culture}} exceeds the scope of applied {{Wiki|medical}} problems. It can be epigraphed with the citation by great humanist [[Nikolai Roerich]] regarding the [[Buryats]]’ attidues towards their [[traditional]] [[medicine]]: “Fortunately, familiarizing with peoples, one can {{Wiki|witness}} sensitivity retained as a | |

| − | + | derly [[Buryats]]. They brought the sole [[extinct]] copy of the Buryat {{Wiki|dictionary}}, very important in a {{Wiki|medical}} [[sense]], too. It was [[touching]] to see their [[crave]] for it to be republished. | |

| − | + | They would say: “Without this [[book]], youngsters have nothing to be educated with; there is so much beneficial information in it”. So, in distant {{Wiki|yurts}} they cared for [[knowledge]]. | |

| − | + | There they would not be opposed to newest [[forms]] of perfection, but would cherish remnants of old [[wisdom]] with the most cordial [[devotion]]” (36, p.63). | |

| − | + | The complex research in objectivation and automation of the {{Wiki|diagnostic}} techniques of [[Tibetan medicine]] was first begun at the Laboratory of Radiobiophysics (LRBPh) of the [[Buryat]] Institute of Natural {{Wiki|Sciences}} (BINS) of the Russian {{Wiki|Academy}} of {{Wiki|Sciences}} (RAS) in 1983 under the leadership of Doctor Ch. Ts. Tsydypov as a priority project. | |

| − | This | + | The {{Wiki|distinctive}} feature of the approach which is being devel oped at the LRBPh is its clear inter-science [[character]]. This approach combines the {{Wiki|solution}} of mathematic and technical problems for designing the {{Wiki|diagnostic}} complex with the profound [[investigation]] of [[Tibetan]] original texts, the {{Wiki|theory}} of [[Tibetan]] pulse diagnostics in particular. |

| − | + | This is be cause the [[Tibetan medical literature]] at our disposal de scribing various types of pulse, supplied with graphical illustrations, presents the [[Tibetan]] pulse diagnostics as an elaborate {{Wiki|diagnostic}} method which is based on the comparison of {{Wiki|data}} obtained from different parts of the [[body]]. | |

| − | + | The frequency of the pulse, the strength of the pulse beating, the [[degree]] of the pulse filling, the [[character]] of the interchange of strong and weak tones, the [[character]] of the rhythm breaks all these must be taken into account and all these can be registered with the help of {{Wiki|modern}} equipment. Thus, registering pulse signals and their subsequent processing and deciphering will make it possible to translate the objective contents of the [[Tibetan texts]] into the [[language]] of modern [[science]], which will permit correlating this or that type of pulse with a certain disfunction of the {{Wiki|organism}} or with a certain {{Wiki|disease}} according to the {{Wiki|classification}} of {{Wiki|modern}} {{Wiki|European}} [[medicine]]. | |

| − | + | Now a number of problems concerning the development of a device registering pulse waves six zones on the radial {{Wiki|arteries}} of [[human]] wrists, the methods of processing pulsograms and the ways of their [[interpretation]] are being partially solved. That is why in the near {{Wiki|future}} we plan to | |

| + | improve the {{Wiki|diagnostic}} complex, the techniques of processing and interpreting pulse waves, i. e. further broadening {{Wiki|diagnostic}} capacity of the complex. | ||

| + | |||

| + | This level of solving the problem of the [[Tibetan]] pulse diagnostics permits the {{Wiki|diagnostic}} complex to work effectively in the clinic [[conditions]]. However the [[physical]] and physiological [[nature]] of pulsation and the ways of interpreting it in [[Tibetan medicine]] remain insufficiently investigated. Understanding its meaning is a key to mastering pulse diagnostics as well as the {{Wiki|theory}} and practice of [[Tibetan medicine]] as a whole system. | ||

This problem comes from the depth of the [[Buddhist]] | This problem comes from the depth of the [[Buddhist]] | ||

| − | {{Wiki|world view}} where the primary “bricks” of the [[Universe]] are | + | {{Wiki|world view}} where the primary “bricks” of the [[Universe]] are “the [[great elements]]” (mahabhuatas): “[[earth]]”, “[[water]]”, “[[fire]]”, “[[air]]” and “[[space]]”. Combinations of these [[elements]] determine the pulsation in a [[human]] {{Wiki|organism}}, and [[form]] what is called, from the view point of [[Tibetan medicine]], [[energy]] levels or [[essences]]. |

| + | |||

| + | That is why the problem of investigating the features of pulsations and of the “[[great elements]]” as well as the study of their outer and inner interrelations and interconnections is, in our opinion, of fundamental [[nature]]. | ||

| − | + | The {{Wiki|solution}} of this problem will be a greatest contribution to the [[development]] of our [[physical]] and [[philosophic]] concepts of [[nature]] and the [[characteristics]] of the [[Universe]] and will become the basis for true [[comprehension]] of the real application of the achievements of [[Tibetan medicine]] on | |

[[scientific]] basis in the fields of diagnostics and treatment. It will be a valuable contribution to our [[understanding]] of a different ([[Buddhist]] and [[Indian]]) {{Wiki|culture}}. | [[scientific]] basis in the fields of diagnostics and treatment. It will be a valuable contribution to our [[understanding]] of a different ([[Buddhist]] and [[Indian]]) {{Wiki|culture}}. | ||

| − | We have plenty of [[information]] at our disposal which is contained in [[Tibetan medical]] treatises. This [[information]] presents very specific material difficult for a contemporary {{Wiki|European}}. It requires more effective and convenient [[forms]] of presenting the [[knowledge]] contained in it. For the | + | We have plenty of [[information]] at our disposal which is contained in [[Tibetan medical]] treatises. This [[information]] presents very specific material difficult for a contemporary {{Wiki|European}}. It requires more effective and convenient [[forms]] of presenting the [[knowledge]] contained in it. For the theoretical analysis and the {{Wiki|practical}} application of the know ledge [[information]] of the [[Tibetan]] original {{Wiki|medical}} texts (especially for the objectivisation of the main {{Wiki|diagnostic}} methods of [[Tibetan medicine]] — questioning and [[physical]] observation) an expert system is being developed. This expert system is able to make diagnosis and prescribe the treatment on the basis of the [[information]] of [[Tibetan medicine]]. |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | Objectivation and the subsequent automation of the third {{Wiki|diagnostic}} method ([[feeling]] the pulse) also has difficulties associated with the necessity to create mathematic simulation of the pulse wave, methods of its processing and reading,. The {{Wiki|movement}} of {{Wiki|blood}} in the vessels is a case of a complicated hydrodynamic process the study of which is impossible without mathematic simulation. | |

| − | + | The effectiveness of {{Wiki|computer}} application in {{Wiki|medical}} {{Wiki|diagnostic}} systems depends on how adequate the mathematic simulations are to the {{Wiki|biological}} systems (MSBS), because the [[state]] of [[health]] of a {{Wiki|patient}} is estimated in the values of these simulation. The difficulty of this problem is in insufficient [[development]] of the techniques of the MSBS projecting and of the criteria of their adequacy level. That is why the major part of the MSBS, due to the low adequacy level, find no use, like the models based on the linear {{Wiki|theory}} of the pulse wave [[transmission]] in the artery. | |

| − | + | Another problem is finding the [[physical]] and physio — [[logical]] {{Wiki|mechanism}} of interconnection of palpation zones on the radial artery with the inner {{Wiki|organs}} of a {{Wiki|patient}}. | |

| − | + | We also work at the problem of objectivation the biologically active points (BAP) of [[Tibetan]] and {{Wiki|Mongolian}} [[medicine]] (TMM) for the electrometric {{Wiki|diagnostic}} method. The {{Wiki|matter}} is that these points do not coincide with the BAP of {{Wiki|Chinese medicine}}. [[Tibetan]] and {{Wiki|Mongolian}} [[medicine]] does not speak of the [[meridians]] and its {{Wiki|diagnostic}} methods differ. It is necessary to find the connections between the BAP and the inner {{Wiki|organs}} or functional systems of the organism. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | We also work at the problem of objectivation the | ||

Thus, the aims of the research are the following: | Thus, the aims of the research are the following: | ||

| Line 152: | Line 178: | ||

The {{Wiki|Modern}} Level of Solving the Problem: | The {{Wiki|Modern}} Level of Solving the Problem: | ||

| − | Nowadays in {{Wiki|France}}, Southern [[Korea]], CPR, [[Japan]], [[Taiwan]] and [[Russia]] work is in progress at objectivation and automation of {{Wiki|diagnostic}} methods of {{Wiki|Oriental}} [[medicine]] (of pulse {{Wiki|diagnostic}} in particular). In this research the main | + | Nowadays in {{Wiki|France}}, Southern [[Korea]], CPR, [[Japan]], [[Taiwan]] and [[Russia]] work is in progress at objectivation and automation of {{Wiki|diagnostic}} methods of {{Wiki|Oriental}} [[medicine]] (of pulse {{Wiki|diagnostic}} in particular). In this research the main attention is devoted to the technical problems, first of all to the [[development]] of pulse sensors. |

| − | The {{Wiki|diagnostic}} {{Wiki|computer}} complex which is being developed, whose {{Wiki|methodological}} basis consists in | + | The {{Wiki|diagnostic}} {{Wiki|computer}} complex which is being developed, whose {{Wiki|methodological}} basis consists in diagnostic methods of [[Tibetan medicine]], has no analogues in the [[world]]. |

The research is undertaken in three detections: | The research is undertaken in three detections: | ||

| − | a) The [[development]] of [[information]] and expert | + | a) The [[development]] of [[information]] and expert systems of [[Tibetan]] and {{Wiki|Mongolian}} [[medicine]]; |

| − | b) The objectivation and automation of pulse | + | b) The objectivation and automation of pulse diagnostics of [[Tibetan]] and {{Wiki|Mongolian}} [[medicine]]; |

c) The objectivation of {{Wiki|biologically}} active points of [[Tibetan]] and {{Wiki|Mongolian}} [[medicine]] and the [[development]] of the methods of diagnosing {{Wiki|diseases}}. | c) The objectivation of {{Wiki|biologically}} active points of [[Tibetan]] and {{Wiki|Mongolian}} [[medicine]] and the [[development]] of the methods of diagnosing {{Wiki|diseases}}. | ||

| − | These points of the project can be [[realized]] within 5 | + | These points of the project can be [[realized]] within 5 years. |

| − | |||

| − | years. | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | The research will be done with the help of {{Wiki|linguistic}}, mathematic and experimental methods using our {{Wiki|computer}} pulse {{Wiki|diagnostic}} complex of [[Tibetan medicine]], the expert system “[[Emchi]]” and doctors-specialists in pulse diagnostics – all this will be done in cooperation with the Republican | |

| − | [[Republic of Buryatia]]. | + | Hospital of the [[War]] Invalids of the Ministry of [[Health]], of the [[Republic of Buryatia]]. |

The expected [[scientific]] results: | The expected [[scientific]] results: | ||

| − | a) [[Philosophic]], {{Wiki|medical}} and [[physical]] | + | a) [[Philosophic]], {{Wiki|medical}} and [[physical]] interpretation of the [[mahabhutas]] and the three {{Wiki|principles}} will be proposed; |

| − | + | b) a version of the expert system for diagnosing diseases will be developed. It will include the method of questioning and the method of [[physical]] observation of [[Tibetan medicine]]. | |

| − | |||

| − | b) a version of the expert system for diagnosing | ||

The new approach to the [[comprehension]] of the basic text "[[rGyud bZhi]]" will allow to create a flexible, [[self]] — developing {{Wiki|diagnostic}} system; | The new approach to the [[comprehension]] of the basic text "[[rGyud bZhi]]" will allow to create a flexible, [[self]] — developing {{Wiki|diagnostic}} system; | ||

| − | c) a mathematic simulation of the pulse wave will be developed, 2 or 4 types of pulse will be deciphered, the pulse | + | c) a mathematic simulation of the pulse wave will be developed, 2 or 4 types of pulse will be deciphered, the pulse catalogue will start to be created, the [[physical]] {{Wiki|mechanism}} of the connection of palpation zones with the inner {{Wiki|organs}} and (or) functional systems; |

| − | |||

| − | catalogue will start to be created, the [[physical]] {{Wiki|mechanism}} of | ||

| − | |||

| − | the connection of palpation zones with the inner {{Wiki|organs}} and | ||

| − | |||

| − | (or) functional systems; | ||

d) 2 or 3 groups of the {{Wiki|biologically}} active points of the TMM will be objectivated. Electropunctural {{Wiki|diagnostic}} | d) 2 or 3 groups of the {{Wiki|biologically}} active points of the TMM will be objectivated. Electropunctural {{Wiki|diagnostic}} | ||

Latest revision as of 13:05, 22 January 2016

Folk medicine of the Mongolian people as a legacy of their traditional culture is traced back to deep antiquity.

Most likely, the healing art of the nomadic peoples is first referred to in the Chinese treatise “Nei Ching” of the third century B. C. It says: “In the north there lies a remote, lonely and almost inaccessible country.

The air is very cold there. Its dwellers keep herds of livestock and feed on dairy products. They suffer mostly from cold disorders, treated with cauterization. Thus, cauterization has emerged from the north” (See 40, p.5).

From the sixteenth century onwards, the Tibetan branch of Buddhism of the gelugpa sect had been spreading throughout Mongolia.

The Danjur comprising larger treatises on Ayurvedic medicine as well as the rGyud bzhi (The Four Tantras) (30, 31) and other medical texts were translated into Mongolian.

Medical colleges, similar to Tibetan sman-pa datsan, were opened at monastic centers.

As a result of many-year experiment on the medicinal arsenal used by Mongolian practitioners of traditional medicine, imported raw material was supplanted by local substitutes.

According to the data from the “Encyclopedic Dictionary of Chinese Medicine”, in contemporary Inner Mongolia (China) 50% of raw material is of local origin, about

40% is brought from the Chinese provinces Yunnan, Xi — chuan, Guandung, Kuku-nor, Xinjan, and Tibet, and around

10% only is imported from India, Tailand, and Malaysia

(40, p. 12). The authors of the monograph “Plants of Tibetan Medicine” believe that plants of local origin in Mongolian medicine make 57%, Tibetan and Indian ones 11.6% and 11.25% correspondingly, and Chinese ones 9.56% (27, p.92).

While estimating the data, one has to take into ac — count that Chinese authors are confined within the boundaries of Inner Mongolia only, without considering the flora of the more northern Peoples’ Republic of Mongolia and Buryatia.

Upwards along the meridian, naturally, the percentage of southern species diminishes, what is convincingly illustrated by the medicinal assortment used by Buryat healers.

Zabaikalye flora accounts for 85.06%, Indian species

3.64%, and Tibetan ones 3.46% (27, p.92). Data of the ethnofloral analysis of the "medicinal flora" allow the authors of the “Plants of Tibetan Medicine” to come to a conclusion about uniqueness of the three “strands” of Tibetan medicine under study – Tibetan proper, Mongolian and Buryat.

Only the principles of treatment, perception of unhealthy body, specifics of administering remedies, and others were ob — viously common for them. The medicinal means assortment was sharply different and was most likely created de novo so far traditional medicine of Tibet was penetrating into the ad — jacent countries (27, p.93).

According to Buryat historical chronicles, the Khori and Selenga Buryat tribes gravitated to Zabaikalye in the late sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries, having converted to Buddhism.

The introduction of Tibetan medicine among the Buryats is related by these chronicles with the date of the official adoption of Lamaism as a state religion of the Mongols in 1576.

Since the last quarter of the seventeenth century, several travelers either with diplomatic or scientific purposes passed through the Buryat lands, among them [[Nikolai Spafary (1675), Izbrant Ides (1693), Lorents Lange

(1716), Johan Georg Gmelin (1735), Piotr Simon Pallas

(1772) and others, who recorded valuable information in their diaries and reports regarding economy, household and habits of the Buryats. But, no doubt, Johan-Georg Gmelin was the pioneer to describe Tibetan medicine in Zabaikalye.

Crossing Zabaikalye in 1735, on the Onon-river he encountered a lama-healer; the latter showed him his own treatises, medicines, and instruments and demonstrated some techniques of preparing medicines and therapies.

According to Gmelin, this lama practiced bloodletting, moxabustion, applied cupping-glasses, and owned a significant set of surgical instruments. It was noted, that he was reckoned locally a “superb” oculist.

Noteworthy, Gmelin’s descriptions of Tibetan medicine among the Buryats almost coincides in time with the first reports on this medicine by Dominican Ippolit Dezideri who visited Lhasa in 1716 and stayed there several years, and by doctor Saunders accompanying the British Embassy to Tibet in 1783 (30, p. 2).

The Buryat clergy had widely used the medicine for strengthening its own influence and attempted to assemble lamas-healers in monasteries. It is known that Agvan-Puntsok, Tibetan by origin, the leading lama of the day in Buryatia, was highly esteemed as a physician. And the first physician among the Buryats was Zhimba Akhaldayev who went in 1721 for training to Mongolia, and then to Tibet. According to one of poorly known chronicles, he was a “prominent healer and a man of fortune” (48 p.69). It was he who established the first datsan in Gusinoozersk in

1741. After Akhaldayev, Damba-Dorji Zayayev was educated in Tibet; he also became a known healer (48, p.57).

Tibetan medicine was extensively practiced in Zabaikalye in the eighteenth century; this was reflected in special articles of the so-called “Common Code of Buryats”.

The new stage of the Tibetan medicine development in Zabaikalye was the official establishment of medical colleges – smanba datsans in monasteries.

In 1869 the school of Tibetan medicine was opened at the Tsugol datsan.

Soon, similar establishments were appended to other datsans, like Aginsky, Egitui, Atsagat, Tugnugaltai, Jida, Yangazhin, Kyren, and others.

Training at the medical colleges was modeled after the smanba datsan traditions of Lavran monastery at Amdo (Tibet).

The courses lasted five years, and disciples were expected to memorize the canonic classics of Tibetan medicine rGyud bzhi, to familiarize with its commentaries, formulas, and to become able of compounding remedies.

The title smanramba was conferred upon these disciples who completed the five year course (29, p. 63-64).

The number of disciples at the largest school of Tibetan medicine at the Atsagat datsan reached 50-60 (29).

According to the approximate data, by the end of the nineteenth century in Zabaikalye lamas-physicians totaled 700 whereas the overall numbers of lamas by the First World War had risen to about 15 thousand (31, p. 15). Thus, their correlation was

4.6% from the total number of lamas. Figures for 1923 specify the same proportion: the number of lamas decreased to

9134 (31, p.151), among whom about 500 continued their

practice (19, p. 12), namely a bit more than 5%.

For the entire period of Tibetan medicine existing in

Buryatia, local datsans printed about 20 most significant theoretical and practical manuals on Tibetan medicine in the Tibetan and Mongolian languages. By its value, the Vaidurya-sngonpo is the most impressive xylograph printing, comprising 1284 folios of an average format.

After the October Revolution of 1917 efforts were made to reorganize the datsan medical colleges into “secular” schools for laymen and monks and to introduce classes in anatomy, physiology, diagnostics of diseases according to western scientific medicine” (31, p.7l). In 1924 under the supervision of Prof. G. Tsybikov, famous for his trip to Ti —

bet, there was established the Center of Tibetan medicine and the first school of a new type opened at the Atsagat datsan. In the early 40s the Center was closed, and the la — mas underwent repressions.

As a result of the elimination of the Buryat clergy as the estate, Tibetan medicine was neglected and forgotten in Buryatia for many years.

However, the “dark period” in the history of Tibetan medicine in Buryatia did not result in the complete loss of this important constituent of the traditional culture. In

1968 a group of research fellows of the Buryat scientific

center was commissioned scientific research on the theme “Description of healing properties of medicinal means of Tibetan medicine”.

Since that time, regular studies in the field of Tibetan medicine in Russia have been carried out aimed towards introduction of its many-century positive experience and expertise into practice of modern public health care.

Further, on the basis of this group, there was organised the laboratory of physiologically active substances, and in 1975 the Department of Tibetan medicine established. Since the very beginning, practitioners of Tibetan medicine were involved in research programs of the Department.

Nowadays the Department of Tibetan Medicine of the Buryat Institute of Biology under Siberian Division of the Russian Academy of Sciences is divided into the laboratory of chemical and pharmaceutical studies, the laboratory of experimental pharmacology and pharmacotherapy,

the laboratory of toxicology of medicinal means, and one minor sector of information supply, all staffed with forty-three researchers, including three researchers with doctorate degrees and nineteen candidates of sciences. Internship on profile disciplines is also offered.

The staff has accomplished several scientific and research themes, including the development on applied problems.

theoretical aspect, is the development of recommendations on the principles of translation and adaptation of ancient medical manuscripts.

Within the series of the “Tibetan Medical Literature”, the Atlas of Tibetan Medicine, the complete version of the canonic treatise rGyud-bzhi, the Kun gsal nan zod, and the mNgon mtshar dg’a ston were translated into Russian and published. Monographs on discrete treatises and sections of Tibetan medicine, numerous collected scientific articles and abstracts, bibliographical catalogues, preprints, and newsletters have been published.

In the practical aspect, the most substantial results are: the elaboration of methods of identifying names of medicinal raw material; selection of potentially useful formulas, methods of deciphering and interpreting names of diseases; the patented methods of simulating diseases of the stomach and gall-bladder based on new data.

The methods for obtaining thirty-nine new means and substances, which possess higher pharmacological value as compared to analogues, have been patented; forty-nine kinds of thans (fine ly powdered compounds) have been worked out and introduced into practice.

Research will be continued in these three directions: source studies, translation and publication of Tibetan medical works; creation and introduction of new highly effective preparations based on Tibetan sources; approbation and introduction of rational methods and technologies of treatment and prophylaxis of widely-spread diseases (35, p.

163-167).

The theme of folk medicine in the context of Buryat traditional culture exceeds the scope of applied medical problems. It can be epigraphed with the citation by great humanist Nikolai Roerich regarding the Buryats’ attidues towards their traditional medicine: “Fortunately, familiarizing with peoples, one can witness sensitivity retained as a

derly Buryats. They brought the sole extinct copy of the Buryat dictionary, very important in a medical sense, too. It was touching to see their crave for it to be republished.

They would say: “Without this book, youngsters have nothing to be educated with; there is so much beneficial information in it”. So, in distant yurts they cared for knowledge.

There they would not be opposed to newest forms of perfection, but would cherish remnants of old wisdom with the most cordial devotion” (36, p.63).

The complex research in objectivation and automation of the diagnostic techniques of Tibetan medicine was first begun at the Laboratory of Radiobiophysics (LRBPh) of the Buryat Institute of Natural Sciences (BINS) of the Russian Academy of Sciences (RAS) in 1983 under the leadership of Doctor Ch. Ts. Tsydypov as a priority project.

The distinctive feature of the approach which is being devel oped at the LRBPh is its clear inter-science character. This approach combines the solution of mathematic and technical problems for designing the diagnostic complex with the profound investigation of Tibetan original texts, the theory of Tibetan pulse diagnostics in particular.

This is be cause the Tibetan medical literature at our disposal de scribing various types of pulse, supplied with graphical illustrations, presents the Tibetan pulse diagnostics as an elaborate diagnostic method which is based on the comparison of data obtained from different parts of the body.

The frequency of the pulse, the strength of the pulse beating, the degree of the pulse filling, the character of the interchange of strong and weak tones, the character of the rhythm breaks all these must be taken into account and all these can be registered with the help of modern equipment. Thus, registering pulse signals and their subsequent processing and deciphering will make it possible to translate the objective contents of the Tibetan texts into the language of modern science, which will permit correlating this or that type of pulse with a certain disfunction of the organism or with a certain disease according to the classification of modern European medicine.

Now a number of problems concerning the development of a device registering pulse waves six zones on the radial arteries of human wrists, the methods of processing pulsograms and the ways of their interpretation are being partially solved. That is why in the near future we plan to improve the diagnostic complex, the techniques of processing and interpreting pulse waves, i. e. further broadening diagnostic capacity of the complex.

This level of solving the problem of the Tibetan pulse diagnostics permits the diagnostic complex to work effectively in the clinic conditions. However the physical and physiological nature of pulsation and the ways of interpreting it in Tibetan medicine remain insufficiently investigated. Understanding its meaning is a key to mastering pulse diagnostics as well as the theory and practice of Tibetan medicine as a whole system.

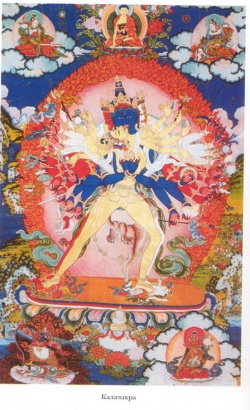

This problem comes from the depth of the Buddhist

world view where the primary “bricks” of the Universe are “the great elements” (mahabhuatas): “earth”, “water”, “fire”, “air” and “space”. Combinations of these elements determine the pulsation in a human organism, and form what is called, from the view point of Tibetan medicine, energy levels or essences.

That is why the problem of investigating the features of pulsations and of the “great elements” as well as the study of their outer and inner interrelations and interconnections is, in our opinion, of fundamental nature.

The solution of this problem will be a greatest contribution to the development of our physical and philosophic concepts of nature and the characteristics of the Universe and will become the basis for true comprehension of the real application of the achievements of Tibetan medicine on

scientific basis in the fields of diagnostics and treatment. It will be a valuable contribution to our understanding of a different (Buddhist and Indian) culture.

We have plenty of information at our disposal which is contained in Tibetan medical treatises. This information presents very specific material difficult for a contemporary European. It requires more effective and convenient forms of presenting the knowledge contained in it. For the theoretical analysis and the practical application of the know ledge information of the Tibetan original medical texts (especially for the objectivisation of the main diagnostic methods of Tibetan medicine — questioning and physical observation) an expert system is being developed. This expert system is able to make diagnosis and prescribe the treatment on the basis of the information of Tibetan medicine.

Objectivation and the subsequent automation of the third diagnostic method (feeling the pulse) also has difficulties associated with the necessity to create mathematic simulation of the pulse wave, methods of its processing and reading,. The movement of blood in the vessels is a case of a complicated hydrodynamic process the study of which is impossible without mathematic simulation.

The effectiveness of computer application in medical diagnostic systems depends on how adequate the mathematic simulations are to the biological systems (MSBS), because the state of health of a patient is estimated in the values of these simulation. The difficulty of this problem is in insufficient development of the techniques of the MSBS projecting and of the criteria of their adequacy level. That is why the major part of the MSBS, due to the low adequacy level, find no use, like the models based on the linear theory of the pulse wave transmission in the artery.

Another problem is finding the physical and physio — logical mechanism of interconnection of palpation zones on the radial artery with the inner organs of a patient.

We also work at the problem of objectivation the biologically active points (BAP) of Tibetan and Mongolian medicine (TMM) for the electrometric diagnostic method. The matter is that these points do not coincide with the BAP of Chinese medicine. Tibetan and Mongolian medicine does not speak of the meridians and its diagnostic methods differ. It is necessary to find the connections between the BAP and the inner organs or functional systems of the organism.

Thus, the aims of the research are the following:

1. To determine the meaning of the main concepts of Tibetan medicine: "wind", "bile" and "phlegm";

2. To develop mathematic simulation of the pulse wave and methods of deciphering it;

3. To create the pulse catalogue;

4. To make clear the nature of the connections be — tween the palpation zones, BAP and the inner organs;

5. To create, in this basis, an integral diagnostic

computer complex of Tibetan medicine.

The Modern Level of Solving the Problem:

Nowadays in France, Southern Korea, CPR, Japan, Taiwan and Russia work is in progress at objectivation and automation of diagnostic methods of Oriental medicine (of pulse diagnostic in particular). In this research the main attention is devoted to the technical problems, first of all to the development of pulse sensors.

The diagnostic computer complex which is being developed, whose methodological basis consists in diagnostic methods of Tibetan medicine, has no analogues in the world.

The research is undertaken in three detections:

a) The development of information and expert systems of Tibetan and Mongolian medicine;

b) The objectivation and automation of pulse diagnostics of Tibetan and Mongolian medicine;

c) The objectivation of biologically active points of Tibetan and Mongolian medicine and the development of the methods of diagnosing diseases.

These points of the project can be realized within 5 years.

The research will be done with the help of linguistic, mathematic and experimental methods using our computer pulse diagnostic complex of Tibetan medicine, the expert system “Emchi” and doctors-specialists in pulse diagnostics – all this will be done in cooperation with the Republican

Hospital of the War Invalids of the Ministry of Health, of the Republic of Buryatia.

The expected scientific results:

a) Philosophic, medical and physical interpretation of the mahabhutas and the three principles will be proposed;

b) a version of the expert system for diagnosing diseases will be developed. It will include the method of questioning and the method of physical observation of Tibetan medicine.

The new approach to the comprehension of the basic text "rGyud bZhi" will allow to create a flexible, self — developing diagnostic system;

c) a mathematic simulation of the pulse wave will be developed, 2 or 4 types of pulse will be deciphered, the pulse catalogue will start to be created, the physical mechanism of the connection of palpation zones with the inner organs and (or) functional systems;

d) 2 or 3 groups of the biologically active points of the TMM will be objectivated. Electropunctural diagnostic

methods of the corresponding diseases will be suggested.

Материал взят из: Abaev N. V., Dr. Ph. Buddhism in Central Asia and Trans-Sayania