A Critical Genealogy of Shamanism in Tibetan Religions - PART VI

Mirroring and Intercultural Mimesis in Discourse about Bon Shamans

My line of argument in this article has involved criss-crossing back and forth between western representations of Tibetan religion and common Tibetan representations of the "other."

My intent is to emphasize how the discourse of Tibetologists repeats (consciously or unconsciously) Tibetan polemics.

In his pioneering study on Orientalism, Edward Said sought to grasp the "sheer knitted together strength of Orientalist discourse, its very close ties to the enabling socio-economic and political institutions and its redoubtable durability."[1]

What Said failed to appreciate in that work is the extent to which Orientalist discourse may be knitted out of strands found in Asian text(ile)s.

By criss-crossing back and forth between western scholarship and Tibetan polemical literature, some of their common discursive strands may come unraveled, revealing that the images of Tibetan religion found in recent scholarship are not fantasies or demonic delusions that western scholars alone have invented.

The point of this exercise is to recognize how western representations of Tibetan religion took form, informed at times by Tibetan descriptions of the other religion.

I do not intend either to place blame or excuse earlier scholars for their representations.

Rather than assuming the moral high ground and criticizing earlier stereotypes of Tibetan religion, my intent is to problematize an assumption made by some Orientalist critics that western scholars and missionaries have invented a discourse unconnected to native representations.

The dialogical reading technique promoted here relativizes the cultural identities of Tibet and the west. The technique of criss-crossing pursued here also relies on metaphors of mirroring and mimicry.

The reduplicated term "criss-crossing" itself, suggests a reflexive movement.

It involves moving betwixt and between the hierarchies and histories of Tibet and the west, showing that the mirror of alterity present in western images of the Tibetan others picks up reflections found in the mirroring historical narratives of Buddhism and Bon.

I have focused on the mirror image in particular as an ambivalent trope with its own agency, not because the mirror image functions as a universal archetype, or because it serves as a key to the psychic unity of mankind.

Mirror images are deceptive, never identical or fixed.

Just as mimicry in the Tibetan context often creates something novel and unusual, so too does the western discourse that mirrors Tibetan polemical categories produce new effects.

As we have seen, Waddell is instrumental in codifying the category of "Lamaism" to describe Tibetan Buddhism, while Hoffmann plays a similar role in the codification of the category of "shamanism" to describe Bon.

Both of these categories have been appropriated by some Tibetans as legitimate (and legitimating) terms to describe and authenticate their own traditions.

Yet once again, these terms are transformed in the process.[2]

Many more examples could be cited to illustrate the "elective affinities" between the historiography of western Orientalists and Tibetan styles of self-representation.

But the above examples are sufficient for my purpose of demonstrating how criss-crossing between the iconic extremes found in Tibetan polemics and western interpretations illustrates a form of "intercultual mimesis."[3]

By reading certain regnant images of the other cross-culturally, we begin to delineate more clearly the intersection of western and Tibetan forms of history.

Criss-crossing is a technique which can illuminate this complex process of intercultural borrowing, bringing out the local flavors and particular cultural culinary genius behind the celebrated "pizza effect."

Much of what follows in this style of analysis is indebted to the insights of the post-colonial theorist Homi Bhabha.

Mimicry is a common ploy used to incorporate the other as almost the same, but not quite, resulting in a stereotype of the aping other as derivative and partial.

Bhabha aptly characterizes this effect of mimicry in the western colonial construction of the other as "not quite/not white".[4]

The racist stereotypes found in colonialist discourse about the Simian Black, whose mimicry of the White Man's manners only makes him more akin to the monkey, or the Lying Asiatic, whose essential duplicity makes him a shady figure according to the white standard of truth, always makes the other recognizable, yet not-quitewhite.

Such stereotypes appropriate the native into a sub-class only to show how inappropriate he or she really is.

Yet what Bhabha explores is not how crude and simplistic these stereotypes are, but rather their dynamic and ambivalent qualities, which produce some anxiety for those who use them.

Aping stereotypes present the other as partial, a somewhat grotesque distortion which, when the mimicking other returns its gaze, is distinctly unsettling to the self-same identity of the stereotyper.

Herein lies the menacing side of mimicry.

The mimic man inadvertently undermines the authority of the original, and the fixity of the white standard of normality starts to slip.

Mimicry always makes a difference that threatens to be total, but not quite, so it must be disavowed, only to bring the other disturbingly close into the presence of the colonialist.

As Bhabha puts it, the discourse of mimicry is constructed around an ambivalence; in order to be effective, mimicry must continually produce its slippage, its excesses, its difference.

The authority of that mode of colonial discourse that I have called mimicry is therefore stricken by an indeterminacy: mimicry emerges as the representation of a difference that is itself a process of disavowal.[5]

The ambivalence of mimicry leads to a kind of double-trouble, or better yet, a double agent.

Situated in a shifty position between difference and sameness, mimicry assumes an agency all its own, without a subject.

As a form of imperfect repetition, mimicry seems to produce unanticipated effects: "the whole question of agency gets moved from a fixed point into a process of circulation.... Mimicry at once enables power and produces the loss of agency."[6]

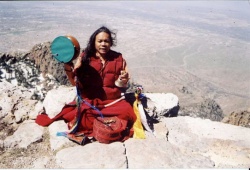

The ambiguous nature of mimetic agency can be illustrated in the latest manifestation of Tibetan and Bon "shamanism" to appear in the west.

With the anthropological studies of Nepali and Tibetan religion, shamanism appears to have earned a widespread currency in academic circles. Yet its value is even more inflated in popular spiritual circles, especially among American New Age adherents.

Evidence for the commodification of shamanism can be found on the Internet, where one can buy shamanic paraphernalia, and in the popular spiritual literature that has flooded the American market for consumption by new-age enthusiasts.

In magazines like Shaman's Drum and in popular do-it-yourself shamanic guidebooks, the experiential benefits of shamanic techniques are touted, and the ancient wisdom of the shaman, who is in contact with another "separate reality," is pursued.

The connection between the anthropologist's fascination with shamanic experience and the New Age participant in shamanic vision quests is no mere coincidence.

Many neo-shamans read ethnographic accounts of shamanic experience as a script for enactment.

Indeed, it was Eliade's proposal that students of religion practice "creative hermeneutics," meaning that they ought to strive towards reliving and recreating the sacred experiences and events of the past.

This message has been adopted wholeheartedly among the contemporary apologists of shamanism, who read Eliade's study of Shamanism as a guidebook for their own ecstatic vision quests.[7]

Understandably, savvy American fashion designers have sought to cash in on this opportunity to sell Tibetan shamanic exotica as the "latest" in primitive chic.

In a 1995 J. Peterman Company Catalogue, one can find a "Tibetan Shaman's Jacket and Cap" for sale, advertised in the section called "Booty, Spoils & Plunder:" It's official. Crystals are out, Tibetan Buddhism is in.

The monasteries are springing up across America; stars of Hollywood, Rock, and Wall Street are chanting Om mani padme hum.

But why play catch-up when you can be a jump ahead? Long before Buddhism came to Tibet, native Bon shamans were doing quite nicely without having to give up (as good Buddhists must) a belief in one's personal existence.

Empowered by ceremonial jackets like the one you see here, they focused on practical matters like curing toothaches and assuring a bumper crop of Hordeum vulgare.

They could fly through the air, communicate by telepathy (cheaper than MCI), do interesting things to their enemies. Isn't there someone you'd like to torment, perhaps launching nine kinds of destructive hailstorms against? Authentic Bon shaman's jacket, handmade in northern India by Tibetan refugees who know how.... Price: $175.

What is striking about the J. Peterman image of the Bon "shaman" is that he is less a master of ecstatic trance and a spiritual healer than a powerful magician whose jacket represents "booty, spoils and plunder."

We might recall that according to Bon histories, the exotic emblems (including the tiger and leopard fur-lined capes and jackets) worn by the Bon priests in ancient times were granted as gifts by the Tibetan kings, in reward for their role in suppressing demonic enemies.

The kings decorated the bodies of their Bon priests with the booty and spoils from the defeated countries, and their bold display of these emblems was meant to embellish the priest's power as a form of metonymic domination.

Today, the Bon "shaman" jacket is less a reward for power than a symbol of the aspiration to power. The advertisement even proclaims "You bet you'll get the table you want when you wear this one."

What makes the J. Peterman advertisement even more revealing is its suggestion that Tibetan refugees, who fabricate "authentic" Bon jackets, are now active participants in the western consumer's appropriation of Bon shamanism.

Today one can read notices in Shaman's Drum or attend New Age institutes for retreats with authentic Tibetan masters, where "the ancient shamanic techniques of Bon" are taught.[8]

Following in the footsteps of Carlos Castenada, people sign up for Tibetan Bon seminars on Shamanism hoping to meet the Tibetan Don Juan. These examples illustrate how "shamanism" has become commodified into a popular image of Bon, not only for western consumers, but for Tibetan Bonpos who participate as well.

The Tibetan Bon teachers have discovered their own identity as "shamans" by looking into the mirror of alterity that western disciples hold up to them.

Continue Reading

- A Critical Genealogy of Shamanism in Tibetan Religions PART I: Introduction

- A Critical Genealogy of Shamanism in Tibetan Religions - PART II

- A Critical Genealogy of Shamanism in Tibetan Religions - PART III

- A Critical Genealogy of Shamanism in Tibetan Religions - PART IV

- A Critical Genealogy of Shamanism in Tibetan Religions - PART V

- A Critical Genealogy of Shamanism in Tibetan Religions - PART VI

Footnotes

- ↑ Edward Said, Orientalism (New York: Vintage 1978), p. 6.

- ↑ Two well-known Tibetan scholars in exile, Samten Karmay and Tsultrim Kelsang Khangkar, have accepted the term "Lamaism" as an appropriate term for describing the Lama-based Buddhism of Tibet. See K. Dhondup's interview of Tsultrim Kelsang appearing as "‘Lamaism' is an Appropriate Term" in Tibetan Review, 13.6 (June 1978), pp. 18-19. Likewise, Tenzin Namdak, the leading scholar of Bon living in exile, has come to embrace the term "shamanism" to describe Bon, as has his student Tenzin Wangyal, who leads weekend retreats on Tibetan shamanic practices.

- ↑ I borrow the phrases "elective affinities" and "intercultural mimesis" from Charles Hallisey's article "Roads Taken and Not Taken in the Study of Theravada Buddhism" in Curators of the Buddha: The Study of Buddhism Under Colonialism, ed. by Donald Lopez (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1995), pp. 31-61. Hallisey defines intercultural mimesis as "when some aspect of a culture of a subjectified people influenced or otherwise enabled the investigator to represent that culture." (p. 34). For a recent application of this model to Buddhist studies, see Richard King's Orientalism and Religion: Postcolonial Theory, India and ‘The Mystic East' (London: Routledge, 1999), and especially his section on "Intercultural Mimesis and the Local Production of Meaning," pp. 148-160.

- ↑ Homi Bhabha, "Of Mimicry and Man: The Ambivalence of Colonial Discourse" in The Location of Culture (London: Routledge, 1994), p. 92.

- ↑ Bhabha, "Of Mimicry and Men," p. 86

- ↑ Robert Young, "The Ambivalence of Bhabha" in White Mythologies: Writing History and the West (London: Routledge, 1991), p. 148.

- ↑ For a very insightful analysis of western neo-shamanism or parashamanism, see Ronald L. Grimes chapter on "Parashamanism" in the revised edition of Beginnings in Ritual Studies (Columbia: University of South Carolina Press, 1995), pp. 253-268.

- ↑ For other examples of New Age appropriations of Tibetan religion, see Frank J. Korom "Old Age Tibet in New Age America" in his edited volume Constructing Tibetan Culture: Contemporary Perspectives (Quebec: World Heritage Press, 1997), pp. 73-97. Another version of Korom's essay appears as "The Role of Tibet in the New Age Movement" in Imagining Tibet: Perceptions, Projections and Fantasises ed. by Thierry Dodin and Heinz R鋞her (Boston: Wisdom Publications, 2001), pp. 167-182.

Source