Advice on Practicing Buddhism in the West

Alexander Berzin

Moscow, Russia, November 2005

Unedited Transcript

How I Came to Buddhism

Sasha asked me to speak this evening about Buddhism in the West, and to start it with a little bit about myself as an introduction to how I came to Buddhism, as a way of illustrating Buddhism in the West.

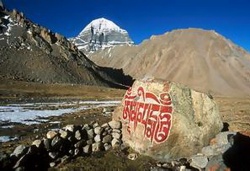

I was born in United States in New Jersey in 1944, and from a very early age I was very interested in Asian things. So I started doing yoga with a friend when I was thirteen and read whatever was available in the 1950s in English about Buddhism, which wasn’t very much. And then in university, although I started studying chemistry, I took a subject on the culture of Asia. I was 17 years old and it spoke about how Buddhism went from one civilization to another in Asia, and how it was adopted and translated to each culture. And after hearing that lecture, everything was clear to me: this was exactly what I wanted to do. And I’ve been doing that ever since, working on the whole process of how do you transform and bring Buddhism, in this case, to non-traditional societies outside of Asia. So I basically then changed my major topic and I started studying Chinese and that led to Japanese and that led to Sanskrit and that led to Tibetan.

So this was before there were Dharma centers in the West, so it’s a very different situation from the way it is now. I think that people in those days who were drawn to Dharma were drawn to it primarily for karmic reasons; it just sort of came up from, the only way to describe it is past karma. And I did meet Geshe Wangyal, the great Kalmyk Mongol Lama who was in United States at around the time that I started to study Tibetan. But at that point my university was not very close to where he was living, and I was only able to visit him sometimes, but I didn’t really have the opportunity to study with him.

But Robert Thurman was in all of my classes at Harvard. We were very good friends. And he had been in India with His Holiness the Dalai Lama, and he told me about Tibetans and that it was possible to go there and study with them. So, I applied for a Fulbright Fellowship, which is a scholarship to study in foreign countries, and I went to India to do my doctorate dissertation research. So that was in 1969, I was 24.

Now, the approach to Buddhism in those days in the universities and elsewhere in the West was that, basically, Tibetan Buddhism was dead. It was like ancient Egyptian studies. And I was always wondering what it could possibly be like to think like this, think in terms of the Buddhist teachings. But when I went to India and I met His Holiness the Dalai Lama very shortly after I arrived, I soon learned that it was all for real. It was still alive, and that it was actually possible to practice Buddhism. And here were people who actually knew what the texts meant; they weren’t like professors in universities who were basically guessing, like doing a crossword puzzle in a newspaper. So I started to do meditation practice and I studied with a teacher there, Geshe Ngawang Dhargyey. And His Holiness the Dalai Lama built the Tibetan library a few years later in Dharmsala, and he asked Geshe Ngawang Dhargyey to be the teacher there for Westerners, and I asked, “Could I be a help as well?” And His Holiness said, “Yes, but go back, hand in the dissertation, get your degree and come back.” So I went back to Harvard, handed in my dissertation, said “no thank you” to a teaching job that they had found me at another university and went back to India. Of course my professors all thought I was absolutely crazy.

And I lived in India for 29 years, working with the Tibetans, helping to establish the Translation Bureau at the Library. And I studied primarily with Serkong Rinpoche, one of the teachers of His Holiness. And I was very fortunate I was able to be trained by him in a very traditional type of way, like a medieval apprentice. Basically, he recognized that we had the karmic relation for that and he just started to train me from the very beginning to be his translator, and eventually to be able to translate for His Holiness the Dalai Lama. So I was Rinpoche’s secretary for English, and disciple and translator, travelled around the world with him, and basically had unbelievable opportunity for nine years to be with him before he passed away.

And then after he passed away, I started to be invited around the world to teach as well, and I was also doing some translations for His Holiness the Dalai Lama by this point. And I helped to do many projects for His Holiness around the world, to make arrangements, and wrote many books. And then I decided that in order to be able to do a large website which I now have and more books and have easier communication, [it would] be easier to move to the West, and so I moved to Berlin, Germany.

So I’ve been living there for the last seven years and teach a little bit. But mostly I work on this big website, www.berzinarchives.com, because I have about thirty thousand pages of my manuscripts, things I have written and translated, and I don’t want them thrown in the garbage when I die. And I’m having it translated into other languages as well: Russian, Mongolian, German, etc., and soon they will be online as well.

So, that’s what I do and what I’ve done; I suppose it’s not terribly typical of how Western people get involved with Buddhism and how their life unfolds. But I’ve always seen my position as that of a bridge. In order to be a bridge you have to have two foundations, one on each side of the river or whatever it is the bridge is going over. So I had one foundation in the West and I was able to travel to so many countries all over the world, so I got to know the different cultures that would be areas that people are interested in Buddhism – where they were wanting to have Buddhism come. So I have one foundation in the countries that I was going to, but then I have the other foundation very firmly planted with the Tibetans and traditional Buddhist culture.

Understanding Traditional Tibetan Culture

And I think that for us Westerners to be able to become involved with Buddhism – particularly Tibetan Buddhism – it’s very important to have some appreciation of the traditional culture that it’s coming from. Because without understanding the context within which Buddhism arose and from which it’s coming to us, and particularly without understanding the culture of the Tibetan Lamas that are coming to us, we just open ourselves up to a tremendous amount of misunderstanding. You see what I did was I basically fit myself into Tibetan culture, traditional culture.

What was the traditional role for a foreigner who came to Tibetan culture and wanted to study? Well, that position was one of a translator. So I asked them to train me to be a translator. And with that role, Tibetans knew how to relate to me, and I accepted that and they accepted that, and so it worked. But if we don’t fit to a traditional way of thinking, particularly in the beginning, then it’s very difficult to really get into Buddhism. I think nowadays, it’s certainly not necessary first to adopt Tibetan culture, or Oriental culture, or any traditional Asian culture ourselves; we don’t have to be like monkeys imitating another culture. We don’t have to change our diet and change our clothes: that’s certainly not necessarily. But at least if we understand where it’s coming from, we’ll have less projections and less confusion.

So, in traditional Tibetan culture, people are born into certain cultural sets of beliefs. So people take totally for granted things like karma, rebirth, that there’s such a thing as enlightened beings. There’s an appreciation of the value of becoming a monk or a nun and great respect for that. And if you wanted to actually study and practice Buddhism, you have to become a monk or a nun. And when you became a monk or a nun, then you devoted absolutely full-time to the Dharma – studying, practicing – and of course we should not discount the fact that there are people who have to cook the food and collect the firewood and collect the water and so on. Obviously, one has to maintain the monastery as well. But being a monk or a nun, you didn’t have to go out and get a job, and you didn’t have to support a family. And the men and women were separate.

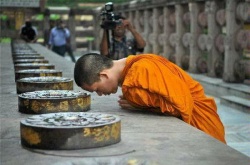

Lay persons really didn’t have very much opportunity to study Buddhism. Lay persons would go and say mantras, for example, circumambulate. They would support the monasteries, and maybe get long life initiations and things like that, and ask monks to come to their house and maybe do some rituals. But everybody accepted the fact that if you really wanted to study, you had to devote full-time to that and become a monk or a nun. Totally accepted. So, when we invite a traditional monk from a Tibetan community, for example, this is where they’re coming from.

Western Cultural Perspective

And here we are in the West and we have none of these things. We have been brought up in different cultures, and we certainly don’t believe in rebirth, most of us, or in karma; or we would say we that believe in karma, actually we just make karma into fate, which is not what karma is all about. And do we really believe that there are enlightened beings? Well, some of us, if we think that there is a Buddha, we might confuse Buddha with God, which he certainly is not. And when we come across figures like Chenrezig, and Tara, and these sort of Buddha figures, many people in the West make them into saints – so it’s Saint Tara and Saint Chenrezig, and offer prayers and light candles to them as if they were an icon in the church.

Certainly most of us do not want to become a monk or a nun. And in fact, people in the West don’t seem to have terribly much respect for those Westerners who do become monks and nuns, which is really a shame. In fact, it’s really very strange that everything gets reversed. In Dharma centers in the West where there are monks and nuns, instead of the lay people serving and helping them, the monks and nuns become the people who are the servants who serve the lay people, and basically run a hotel for lay people who come for weekend retreats. And instead of the monks and nuns even being able to go to the teachings, they have to stand outside and collect the money and make sure that all the administration is running smoothly.

And as lay persons we certainly expected we’re going to be able to get the major focus of study, practice and teachings. But the big problem is we don’t have time. We are very busy. Some of us work, some of us go to school, some of us have families. If we come after work we’re tired, and we have to go through a big traffic jam for instance, like here in Moscow, to get here. And even if we want to listen and want to learn, when we come to some teaching in the evening, we’re so tired that we fall asleep. And maybe we can spare one night, maybe at the most two nights a week, but no more than that. We have other obligations. So, really, this is a problem.

Approaching Dharma Practice with Realistic Expectations

And a lot depends on what do we realistically expect. Now, this is not a very pleasant pill to swallow, but Dharma practice involves basically working on our personalities, and trying to get rid of our negative habits like selfishness, anger, greed – this sort of nasty things. His Holiness the Dalai Lama calls them “trouble makers.” These are the things that make the most problems for ourselves and for others. And Dharma practice involves training ourselves to develop better and more constructive and positive habits. And the difficult pill to swallow is that these are very difficult things to do. Our selfishness and anger don’t go away just like that, going to a couple of lectures once a week or sitting down every day for even a half hour or an hour, which for most of us is a lot of time to sit down and try to meditate and practice. So, our negative habits aren’t going to go away so easily. So, when we come to the Dharma in the West, I think that it’s very important to have a realistic attitude toward it.

Many people come to Buddhism for reasons that aren’t most conducive for progress. Some people come because it’s fashionable, it’s the latest fad. But like fashion in the clothing world, it changes every year or two, so that’s not a very lasting reason for coming to Buddhism. Other people come to Buddhism because they are attracted to exotica, really exotic, far out things, like looking for flying saucers. They’ve read some strange novels that talk about how Tibetans drill holes in people’s foreheads to open the third eye and so on, and they are attracted to such things.

Once I was translating for a Tibetan Lama in New York, Nechung Rinpoche was his name. And in the audience somebody who was looked as though he was on some sort of drug got up and asked a question. He said, “I understand that Atlantis is underneath the earth and the flying saucers are there and they come out from the center of the earth through volcanoes, and my question is ‘Is the earth hollow?’” And the Lama looked at him, very, very seriously and said, “No, actually the earth is flat and square, next question.” So that I thought was the most skilful answer for that because it was even more weird than the question. If we’re looking for exotica, after a while we’re going to be quite disappointed; although the Tibetan culture might be very different from ours in Europe, there’s nothing mysterious about it.

Other people come to the Dharma basically because they’re desperate and they are looking for a miracle cure for either some physical problem or some emotional problem. And that’s very dangerous, to come with that expectation, because with that expectation and hope, we open ourselves up to abuse. Basically people come and say, “Lama, Lama just tell me the magic words, the magic mantra to say. Tell me, I’ll do anything!” And often they are quite abused. But even if we come with these types of motivations in the beginning, motivation can be changed. But a lot of us come just because of curiosity or maybe, as in my case, some sort of karmic thing that sort of drives unconsciously.

Proper Attitude and Approach to the Dharma

Now if we look at some of the traditional texts, we find descriptions of what is the proper attitude, best attitude, for someone to have if they want to approach and study the Dharma. So, an Indian master, Aryadeva, said that first of all, a potential disciple needs to be someone who is impartial. That means without preconceptions. They need to be open-minded. It’s not helpful to come and think “Well, I read a couple of books and I know everything already, so just give me the little icing on the cake to finish it up.” Or having really strange ideas about Buddhism and thinking that this is it, and then we really don’t want to hear anything more, or a very sectarian, like a football-team-mentality, that “This is going to be my sect, my tradition, and everybody else is wrong.” So basically impartial, open-minded, “I’m coming, I want to learn.”

Then the second thing Aryadeva said we need is common sense. In other words, we need to be able to see what is reasonable, what is unreasonable in the teachings. The traditional example that’s given is if you read in one text you need to wear warm clothing and in another text that you need to wear very light clothing – common sense, you understand that in the winter you wear warm clothing and in the summer you wear the light clothing.

Buddhism is intended to help us to think for ourselves. We don’t have the army mentality in Buddhism that the teacher tells us to what to do and we say, “Yes sir!” and just don’t question at all. That’s not the Buddhist way. We can read about the qualifications of a spiritual teacher, how a spiritual teacher needs to act, and so on. And when we see somebody who’s supposedly teaching and is not acting like that, common sense tells us something’s wrong here. And you ask, investigate, what’s going on.

Then the third qualification was to take interest, sincere interest in the Dharma. So what does that mean? For that, we can look at another text by a Tibetan master from the Sakya tradition, by a great lama named Sonam-tsemo. He wrote a text called The Gateway to the Dharma, and he said that there are three things that we need in order to get into the Dharma, which basically elaborate this point from Aryadeva. We need to recognize and acknowledge the suffering in our lives. In other words why we are taking interest in the Dharma? Is it just out of curiosity, to be able to say interesting things to our friends over a cup of coffee? Or is it because we’ve been thinking about our lives, and “I recognize and acknowledge that I have problems, things are difficult – difficult in terms of how I deal with other people, I get angry, things don’t go my way and I don’t deal with it well, and it’s difficult for me to get along with my parents, my society.”

So, first we have to recognize and acknowledge them. And then have the sincere wish to get out of it, not just to make the best of it. There are many approaches in psychology which say, “Well, life is tough, and your situation is difficult, and just learn to live with it and don’t complain too much,” just sort of “Keep quiet and don’t get angry.” But that’s not what Buddhism is aiming for. We want to get out of this!

And then the third thing – in addition to recognizing the suffering and the sincere wish to get out of it – the third thing is to have some knowledge of the Dharma so that we have some conviction that the Dharma shows us the way out of it. So we need to know something about the Dharma in order to take interest in it, and we’re taking interest in it in terms of following the Dharma as a way to help us get out of our difficulties. Then we have interest in actually applying the Dharma to our lives, which is the whole reason to get involved with the Dharma.

And that’s really what renunciation is all about. We call that “renunciation.” We basically renounce, want to get rid of, our suffering and its causes; and we’re willing to give it up. And we are looking then to the Dharma as a way to help us out of that, which is basically what refuge is all about, isn’t it? And that’s what refuge is all about. Refuge is putting this direction in our life.

So, even if we are Western people who are not able to put our full time into Dharma practice, we’re not able to become monks and nuns and give up everything and we don’t have monasteries that are going to support us financially. And even if we have to deal with the realities of work, and school, and family, and traffic and so on, then still if we have all of these points that these great Indian and Tibetan masters have mentioned, then we can benefit a great deal from the Dharma. We find that so many different masters have said the same thing, basically.

Now, the amount of time that we are able to devote to the Dharma is basically a function, I think, of how much we understand. You know, to practice the Dharma doesn’t really mean to take out a half-hour or however long we want to take out, and just sit quietly, and recite something, and go off into some sort of dream world. Many people do that, but basically it’s an escape. And although it might relax them, which would be helpful of course, they don’t really understand how to apply Dharma to their daily lives. So they become quite schizophrenic – their practice is one thing and the daily life is another thing. The classic example is somebody meditating and somebody comes over to them and asks them a question, and he get angry, you know, “Don’t bother me. Go away, I’m meditating on love!”

Applying Dharma to Our Daily Lives

But the more that we understand the Dharma, then the more we can understand how it really does apply to our daily lives. And to apply Dharma to our daily lives requires, first of all, listening to the Dharma, learning it. Now we have to understand the method with which Buddhism is taught. It’s a little bit like trying to put together a jigsaw puzzle – we get a little piece here, another little piece there, and another little piece there, and it’s our responsibility, our job to put it together. And all these pieces fit together in many, many ways, not just in one way. Also, life is very complicated, and because life is complicated, the Dharma teachings and practices are also very deep and very extensive and very complex. So we have to hear a lot of teachings or read a lot of books, and try to use our common sense to put it together. And be open-minded – as Aryadeva said, if we don’t understand something, don’t immediately say, “Well, this is stupid,” and reject it just because I don’t understand it. But have that open attitude which says, “I don’t understand this, it seems very difficult” – let’s say the teachings on the hell realms, which most Western people really don’t want to deal with at all – and say, “OK, I don’t understand this. I’ll leave it for a while and maybe later I’ll understand what they’re talking about.” You know, these teachings on rebirth and all the different life forms – these things are very difficult for us as Westerners to relate to. But it’s not fair to the teachings to just say, “Well, this is just some psychological thing,” or “It’s stupid and you can do without it.”

Then, when we get some pieces of the puzzle together from listening, then we have to think about it. And the whole process of thinking about it is basically to try to understand it. And for that we use common sense. And if something is really, really strange, ask – ask questions. And if we don’t have a teacher available to ask questions to, ask our fellow students, read more. Certainly, so many things that are also available now in books and on the Internet; none of these were available when I was a young person. Now, in the modern world, a lot of things are available. The problem with the Internet, of course, is that there’s a lot of garbage in the Internet as well, so we need to use common sense. And anything that makes Buddhism into some sort of weird occult thing is usually garbage. After living with the Tibetans for twenty-nine years, I can tell you that it’s not this occult, mystical people flying through the air and stuff like that. They are just human beings, like everybody else. Many of them are very, very highly developed – this I can say for sure – but they’re not flying through the air and performing miracles.

An Open-Minded Approach

So we need to keep our feet on the ground when approaching Buddhism. Even when the forms that we will meet when we study the traditional Tibetan Buddhism might be very alien to us, that doesn’t mean that they are occult and weird; they’re just different. My main teacher, Serkong Rinpoche, used to scold me all the time – it was very helpful for me, actually. And I remember once I was translating for him and he was explaining the way that Tibetans do arithmetic. They add and subtract and it’s different from the way we do it in the West. And my remark about it, I said to him, “Wow, this is really strange,” and he yelled at me. He said, “Don’t be so arrogant. It’s not strange, it’s different.” To call it strange is just a sign of your arrogance. And this is very true.

So, once we have understood something of the teachings, then meditation is what we do to build it up as a beneficial habit. By practicing, for instance, being patient. And meditation isn’t something that we do only sitting on a cushion in our room, but we can do this all day long. In fact, we can do thinking about the Dharma teachings all day long as well. But if we haven’t really heard many teachings and we haven’t thought about them and tried to understand them, then we are just going to be filled with indecisive wavering, doubt, and how can we make any progress?

Overcoming Discouragement

Now, one of the most important things to remember in doing Dharma practice is that the nature of samsara is that it goes up and down. And that’s true not only of rebirth and this type of larger samsaric vistas, but it is very, very true in terms of our daily practice. Some days our practice goes well, some days it doesn’t; some days we don’t even feel like practicing, other days we are very enthusiastic. That is totally normal.

And when things don’t go well, what do you expect from samsara? That it’s going to be paradise? It’s samsara. So no way that our practice is going to be linear and every day is going to get better and better and better, and eventually we’ll live happily ever after like in a fairytale. After many years, we might still get upset about certain things. But the point is not to get discouraged.

Well, even if we are not able to put in full-time practices as a monk or a nun – and mind you most monks and nuns aren’t able to put in full-time practice anyway; they drink a lot of tea and do all sorts of other things as well – but no matter how much time we’re able to put into it, don’t expect instant results. Our selfishness and negative habits are very strong, but the point is to work on them. As Shantideva, a great Indian master, said, “The time when my disturbing emotions could defeat me is over. Now I am going to get rid of them, and I’m not going to give up.”

And His Holiness the Dalai Lama said, “Don’t look in terms of short term practice to see whether or not we have made any progress; look over the last five years, if you’ve been practicing that long. And even though, day to day, they’ll go up and down; if after five years you find that you don’t get as upset as you used to get, and you’re able to deal with life’s difficulties a little bit more calmly, then you’ve had some progress.

And don’t be satisfied with just a little bit of progress, you know, and say, “Oh, well, now it’s enough.” But if we really think about the nature of the mind, which is not an easy thing to understand, then we will get confidence that it is possible to actually get rid of all this junk that’s causing us our problems. And when we have living examples of His Holiness the Dalai Lama and others that can inspire us by their example of what is possible to achieve – whether they’re enlightened or not, who am I? I’m not qualified to be able say – but look at the way they are able to handle difficulties. Can you imagine being like His Holiness the Dalai Lama, and how many hundreds and millions of people in China and elsewhere consider him the worst person in the world, and yet it doesn’t bother him, he is able to deal with that. I mean if one person thinks we’re terrible, we get all upset and we cannot deal with it.

And even if we’ve never met him, even if we’ve never seen him in person, still, we’ve read about him, having seen videos and things with him – they’re inspiring. And that inspiration keeps us going even when times are difficult and we’re experiencing the down phase of samsara’s up and downs.

Inner Transformation without a Costume

One final point about the practice of the Dharma – not just in the West, but in general – is one of the pieces of advice that we find in the lojong, the mind training teachings, which is to transform ourselves inside but outside remain normal. That means the main work that we do is on our personalities. We don’t have to go around wearing twenty red strings around our neck and with the rosary and strange clothes and stuff like that, because when people see us they think that we are really weird, something really is wrong with this person. And if they think that, how can we help them? They’re not receptive to us at all. There’s nothing wrong with red strings and rosaries if that’s what you find helpful, but you can keep your red string in your pocket, in your wallet; you can keep your rosary also in your pocket or elsewhere, you don’t have to show them around to everybody. In fact, in the tantra teachings they emphasize very much keeping all these things private. If you show them around to people, people laugh at you; they make fun of you; you have to defend it and so on, which takes away any sort of feeling of holiness or sacredness to it. When it’s private, when it’s personal, special to us, that’s all that it needs to be. But externally, we are normal and in this way people will be open to us. We can relate to other people, they can relate to us, and this is very important.

Conclusion

So if we understand the culture that Buddhism is coming from, then we are not going to make unreasonable demands and expectations on ourselves. And we’re not going to make unreasonable demands on the teachers either. It enables us to be more humble. I understand, “I don’t have the advantage of automatically believing in rebirth and automatically having respect for various things. But I have Western education, so that gives me some tools to think about these things. And I may not be able to give full time to Dharma study and practice; I have to lead a practical life in the West.” And so we are not over demanding: “Well, give me everything but I don’t have to listen to it, so give it me instantly in a pill.” But “I have only this amount of time, this is realistic, and so I’m going to practice and do my best with what I have available.”

You see it’s a very fine balancing in the end between not being arrogant on the one hand and not being discouraged and saying, “Oh, I don’t have any possibilities because I don’t have time and so on, so why even bother.” It’s very important not to go to either of these two extremes. But if we’re free of those two extremes, of arrogance and being discouraged, then we just do our best. That is all that we can do without too high of an expectation – be realistic.

And remember, in traditional societies, there was no such thing as Dharma centers. This is a totally a Western invention. People got together, monks and nuns got together to do rituals, but nobody got together to meditate together. That was something you did privately. So we have Dharma centers for lay people – very good. But again, we have to try to avoid two extremes: one is making it into a social club. By that extreme I mean only a social club and nothing more. Or the other extreme which we find in some centers, which is that nobody even knows each other’s names, and you just come in and sit there very formally, and then you don’t talk, and you go out and nobody knows anybody.

What is very helpful with Dharma centers is that we have a group of people who are like-minded in similar interest. So, this is very important to be able to then be friendly with each other, practice the Dharma in terms of being tolerant and patient and kind and so on with each other. Learn each other’s names at least. And when new people come, make them feel welcome, make it a little bit personal. It doesn’t have to be a group therapy session where everybody tells about all their problems. But we can get a lot of support in our practice from each other. And that I think is an important feature in Western Buddhism that can be very helpful. And of course with respect – respect for each other, respect for what we’re doing. And in this way, we can be reasonable and follow the Dharma path with our feet on the ground.

Questions

So, do you have some questions?

Question: Don’t you think that some aspects of the Protestant culture are basically contradictory to certain base forms of main world religions and in particular Buddhist religion?

Alex: I think that when we approach Buddhism we have to be very mindful of what is the cultural baggage that we carry with us that might confuse us in our practice. Remember, the first criterion that Aryadeva mentioned for a proper disciple was that he needs to be impartial, in other words come to Dharma without preconceptions. So whether or not we are speaking about coming to the Dharma from another religious background or from a non-religious background, a cultural background, very often we bring inappropriate attitudes toward the Dharma that cause a lot of obstacles in our practice. And often this is reflected even in the translation terms with which we learn the Dharma. So if we think in terms of virtue, non-virtue, and merit and sin, and good and evil, and all these sort of things, then we bring in from many Western religions the whole concept of guilt, because we are basically bad if we’re not practicing, and that really causes problems in the practice. When we bring in that type of material, this is coming basically from religions that are based on laws which are given from a higher authority. And ethics are based on obedience, and if you don’t obey then you are bad and you get punished, and when you do obey then you are rewarded – although that higher authority that gives those laws we have to obey may be either a heavenly authority or could be a legislative authority, legal laws. We have the same thing in our culture. Or you are a good communist party member or a bad member; it’s the same thing, same mentality.

Whereas in Buddhism, basically when we act destructively we’re doing so not because we’re bad people and we’re guilty, but we do that basically because we’re confused. So we’re confused; we don’t know that acting this way is just going to cause a lot of problems. So the response to someone like that is not, “You’re guilty and you’re going to go to hell,” but compassion. And likewise if we bring in from certain foreign religions or ways of thinking which are not necessarily religions, of the One Truth – that this is the one way and everything else is wrong – that also is going to cause problems in our practice. Whereas the Buddha taught many, many different methods for many different people, and this is very helpful and necessary.

So I don’t think that it’s so helpful to point and say, “Coming from this background is worse and more difficult than coming from that background, this religion or that society or that culture.” I think the main point is to try to be aware of certain ways of thinking which are culturally limited – it’s just coming from one culture, one religion – and not to project it onto Buddhism.

Yeah.

Question: Personally I observe that the Western mind or European mind is more curious and asks more questions w en he studies Dharma than Tibetan or Oriental or Asian mind. So is it somehow at least a bit helpful to ask h more questions or is it an obstacle?

Alex: Actually, asking questions can be very helpful if they’re asked at the proper time. In other words, first we need to get the information and be patient. Let’s say, for instance in a lecture, to wait until the end and then ask the questions. Whereas if you just hear one sentence and then, you know, immediately you jump up and ask a question about what is going to immediately follow, then that’s a little bit interruptive.

But if we look at the traditional Tibetan Buddhism, it is true that the monks don’t ask so many questions directly to the teacher. But what they do do is they debate with each other, and they’ll debate with the teacher as well if it’s just a small number people. And the debate is filled with questions, as if we are intended to question everything in our minds, in our understanding, and then question each other’s understanding, and try to work out the solution ourselves. And the debate is intended to help each other to understand.

The importance of the debate is that we would never question our own understanding as much as somebody else will. We’ll give up much more quickly. If the other person who’s debating against us won’t leave us alone, “You didn’t get that straight, you don’t really understand,” then you ask another question.

And at the end of the debate process, what we are left with is that we actually understand something and don’t have any more questions or any more doubts. And it’s only then that we can really meditate on the topic and really digest it. When we don’t have any more questions, we are sure of our understanding.

So our way of questioning in the West actually is not so helpful for personal development, because what we expect is you just ask the question and you get the answer and that’s it, and maybe, maybe you write it down. And of course you never look at what you wrote again.

And I must say that most Western teachers, myself included, from our Western training we tend to give the answer. But that’s not really the Buddhist method. The Buddhist method is to leave the students to try to figure it out themselves so that they develop their minds.

And again the problem is that we don’t have so much time to spend a whole day or a whole week debating something. We want the instant answer – you type it into a computer and micro seconds later there’s the answer. So the way that we question and the way that traditional Tibetan Buddhists question are quite different.

This is why I said from the very beginning that what I found very helpful for being able to help make the bridge for people is to see, “Well, how do the Tibetans do it?” And then see is there some comparable way that we can do that given our culture, and not just assume that our way of doing things is right.

So whether we do formal debate, whether we just have discussions with each other in a much more informal way, I think that this can be very helpful to discuss Dharma points with each other. And then, if there is something that we really don’t understand and really can’t figure it out, then ask the teacher. But if we do this, we need to also be willing to have the teacher question us and question our understanding, and many people in the West don’t like that because it sounds as though they’re getting an examination and going to be graded like in school.

You see, the debates are done in a very energetic way, it’s true, but it’s also a lot of fun. And so when somebody doesn’t know the answer and says something wrong, everybody laughs at them. And it’s a very good exercise to get over a big ego. And there’s so much debate going on that everybody says something stupid at some point, so it evens out. But for us in the West, if everybody in the class started to laugh when we said something incorrect or stupid, many of us would have our low self-esteem reinforced, which is not so helpful.

You see, most of us Westerners suffer from low self-esteem and most Tibetans at least don’t suffer from low self-esteem. If anything, they suffer from the opposite, which is a little bit too high self-esteem. And so we’re approaching things from a very different background, and this is again our cultural baggage that we bring with us.

And so for Tibetans, you know, a very proud mountain people who think, “I’m correct” and so on, the debate with everybody laughing and so on helps to bring them down. Whereas for us coming with low self-esteem, it makes us just feel worse about ourselves. So what I do with my class is, I wait for a long, long time, many years, until there’s enough of a trust and friendship and warmth within the group for people to feel comfortable enough to then have this type of discussion. But with people who are new and feel insecure in a group, it could be very devastating.

So maybe we should end here for this evening. We end with a dedication. And it’s very important to understand why we have a dedication. If we do something positive like listen to a Dharma talk as we’ve done this evening, it builds up some positive force and understanding. But if we don’t have a dedication, then that’s just positive force for samsara. And so it ripens into maybe being able to have a nice conversation with other people about what you listened to and nothing special. But what we need to do is like with the computer: you have to save the positive force into the folder which is for enlightenment. If you don’t save it in the enlightenment folder, it just automatically goes into the samsara folder. So the dedication is saving it in the enlightenment folder. And backing it up, yes.

So, what we say is, “Whatever positive force has come from this, whatever understanding, may it act as a cause for reaching enlightenment for the benefit of all.” And then really mean it. Then it acts as a cause for enlightenment which is that we want is to be able to benefit everyone. You just do it in your mind; you don’t have to recite some special words. The main thing is the thought. And best to do it is in some words that are meaningful to you. If you like to do it in a ritual way, there’s nothing wrong with the ritual. But do your own ritual, not just “bla bla bla,” which does not mean anything to you.

OK, thank you very much.