Amitabha practice across traditions

Amitabha practice across traditions

Part of a series of short commentaries on the Amitabha sadhana given in preparation for the Amitabha Winter Retreat at Sravasti Abbey in 2017-2018.

- The front-generation Amitabha is suitable for all to do

- Some background on the Amitabha practice

- How to create the causes to be reborn in Amitabha’s pure land

Before going into the Amitabha sadhana in more detail, I want to talk a little bit more generally about the practice and where it fits in.

It’s usually considered a sutra practice, although I think it’s also tantra because there is an initiation into it. But when we do the front generation Amitabha practice, then everybody can do that. It’s good when you do it to have some basis in the determination to be free from samsara, bodhicitta, and the correct view of emptiness. In other words, it’s not a practice that you walk into as a baby beginner, not understanding the Buddhist worldview of the Buddhist idea of how spiritual transformation occurs. If we just walk into it straight off the street, especially people who had theistic religions when they were little, then it looks like you’re just substituting Amitabha for God. Then because you lack the whole philosophical underpinnings and the Buddhist perspective then you don’t get the same result and it can even become more confusing for you. You’re wondering, “Maybe if I practice Amitabha, God is isn’t happy. And if I practice my theistic religion, Amitabha isn’t happy.” People’s minds can get quite confused, so it needs some basis so that you know what Buddhist practice is about.

This practice of Amitabha is in all the Mahayana countries: Tibet, China, Japan, Vietnam, Taiwan, and so forth. It’s a very popular one and it’s done slightly differently in the different countries, according to their usual philosophical perspective and so on.

For example, in Japan there’s much emphasis on Amitabha as an external being. They talk about liberation due to self-effort and liberation due to the effort of others. In Japan it’s very much doing this practice with the attitude of liberation from others, meaning that by relying on Amitabha, Amitabha will liberate you.

Whereas in Tibetan Buddhism, and I think more so in Chinese Buddhism, it’s very much we have to do the transformation ourselves. The practice is a help, and Amitabha’s enlightening activities benefit us, but the effort, the transformation, comes mostly from ourselves.

It’s just different emphases, and some of these emphases depend on the historical period when the Amitabha practice was brought into a particular country. In China, and especially in Japan, it was brought in at times of great difficulty, with a lot of social upheaval. When you bring it into a population where there isn’t widespread literacy, then the people need something to sustain them through those difficult historical times and you need to make it simple so that they can remember it because they can’t read. In ancient times this was the case not only in Asia but all throughout the world. There were certain classes of people that read but not others.

It’s quite different now, but I think to some extent it was very simplified in those difficult times so that it could be become a very widespread practice, which helped people.

This practice you don’t need to be some high level bodhisattva to do. It’s something that we ordinary beings can do.

A lot of this practice involves creating the cause to be reborn in Amitabha’s pure land, which is called Sukhāvatī, or in Tibetan “Dewachen,” it means “the land of great bliss.” The idea of getting reborn there is that all the circumstances for Dharma practice are very conducive in Sukhāvatī. You don’t have to go to work. You don’t have to pay taxes. There are aren’t problematic family situations because nobody’s born in a family, you’re born in lotuses instead. Then the whole environment is very conducive. There are buddhas all around. They say that the wind that blows through the trees teaches the Dharma. Amitabha’s there. You have everything you could possibly need. You don’t have to go looking for food or clothing or medicine or shelter.The environment’s very hospitable. The ground is soft. No thorns. They’re not building a smelter. There’s no climate change. You don’t need to get involved in a lot of social activities. You can really focus on your practice. That’s the benefit of being reborn there.

His Holiness really emphasizes that the motivation to be reborn there must be a bodhicitta motivation. If your motivation to be reborn there is just so *I* won’t go to the lower realms, because if you’re born in Sukhāvatī, although you aren’t free from samsara yet, you also aren’t in samsara and you can’t get reborn in the lower realms after that. But if that’s your motivation for being reborn there—”I don’t want to be reborn in the lower realms and I’m just looking out for me”—then His Holiness is not at all in approval of that kind of attitude and motivation for doing the practice.

Similarly, thinking that if you do powa, and that doing powa and getting some signs on the top of your head and things like that, that just doing that is enough to secure a good rebirth, you don’t have to do anything else, also His Holiness does not have much respect for that kind of attitude. His attitude is very much what he always says, “We’re the ones who created the problem, so we’re the ones who have to change and fix our problems.” It’s our responsibility to take care of ourselves and to take care of other sentient beings, and not to just look for a quick, cheap, and easy way to our own personal enlightenment sot that we can have a nice nap afterwards.

He often says that, how he thought when he started practicing: “Oh, I’ll attain awakening and then I can have a nice sleep and relax.” No, this is not the attitude that he advocates.

In relation to our world, Sukhāvatī is in the west. Akshobhya’s pure land is in the east. They say it’s very, very far away. I haven’t heard the distance in light years so please don’t ask me that question. And it also isn’t perceivable by our eyes or our gross senses. It is perceivable by the mind, because it’s the mind that takes rebirth in Sukhāvatī. We start that process by visualizing Amitabha’s pure land and visualizing being in it now because what we aspire to and what we familiarize ourselves with now creates our experience in the future. In the same way that our actions create our experience in the future, generating the intention, the aspiration to be reborn in Sukhāvatī repeatedly puts that in our minds in a very deep way, and then, hopefully, when we die—since we’re creatures of habit—aspiration will again arise very strongly at the time of death and that will propel us into rebirth in Sukhāvatī.

The realization, or the actualization, of any pure land—Sukhāvatī or any other—is not without causes. It’s not just magic. Like everything else it’s a dependent arising. Here in particular one of the chief causes is Amitabha’s unshakable resolve to establish this kind of pure land. Before he was Amitabha buddha, he was a bodhisattva monk named Dharmakara. As all bodhisattvas do, he thought about how best to benefit sentient beings, and what he thought was there are so many pure lands that exist but they can’t be reached by people unless they abandon nonvirtue. You have to somehow be an above-average person to be born in these other pure lands. You have to have created a great deal of merit, assiduously studied the Dharma, done a lot of purification. Otherwise you can’t reach those other pure lands. So Dharmakara was very concerned about this. What about the average Joe Blow who has negativities and hasn’t done that much practice and still needs some help? With a lot of compassion for ordinary beings he made these unshakable resolves. Remember when we make the six perfections into ten, one of them is unshakable resolve. He made these unshakable resolves. Depending on those unshakable resolves he was able to create this pure land, because a lot of those resolves have to do with who can be reborn in his pure land, what the pure land is going to be like, and so forth.

It’s not just Amitabha’s unshakable resolves that established it, it’s also due to his accumulation of merit and accumulation of wisdom. Those two collections of merit and pristine wisdom are also essential for a buddha in order to create this kind of place where we ordinary beings can be reborn.

He had such a strong intention to liberate living beings by creating a pure land where ordinary beings—instead of aryas—can be reborn.

There are some aryas born in Sukhāvatī. The hearer aryas are born there. Many of them, they attain arhatship. That is nirvana with the remainder of their coarse body. Then when they pass away they have nirvana without the remainder of their afflictive body. Many of them are born at that time in Sukhāvatī. I don’t know if all of them are born there. I think just some of them are born there. But there are nine different kinds of lotuses in Sukhāvatī. What kind of lotus you’re born in and how soon that lotus opens depends a lot on your mental state. The srāvakas—the hearer arhats—are born in lotuses that are closed because they lack the bodhicitta. They’re in their meditation on nirvana and the emptiness of all phenomena, but the buddhas have to wake them up and tell them to generate bodhicitta, and then after they generate bodhicitta their lotuses will open.

In the same way there can be some people…. If you create very heavy negative actions like the five heinous actions, usually that’s a direct ticket to the hell realms. But if somebody engages in Amitabha practice and practices very well, and does a lot of purification, they can still be reborn in Sukhāvatī, but again not in a fully open resplendent lotus because they still have a lot to do, a lot of purification.

Similarly, people who have doubt. They pray to be reborn in Sukhāvatī, but “does this really happen,” then they can be reborn there, but again, in a lotus that isn’t completely, fully open and radiant.

Even if you’re born in a closed lotus, you’re there. It’s like getting on the last plane out of Iraq before something happening. The people fleeing Vietnam, getting on the last plane out of Vietnam before everything fell apart. You’re still there. You still got born in Sukhāvatī. But there’s some work to do and things to happen first before you can benefit as much as you want to from it.

I think I’ll stop there for right now and then continue later. It gives you some idea of the practice.

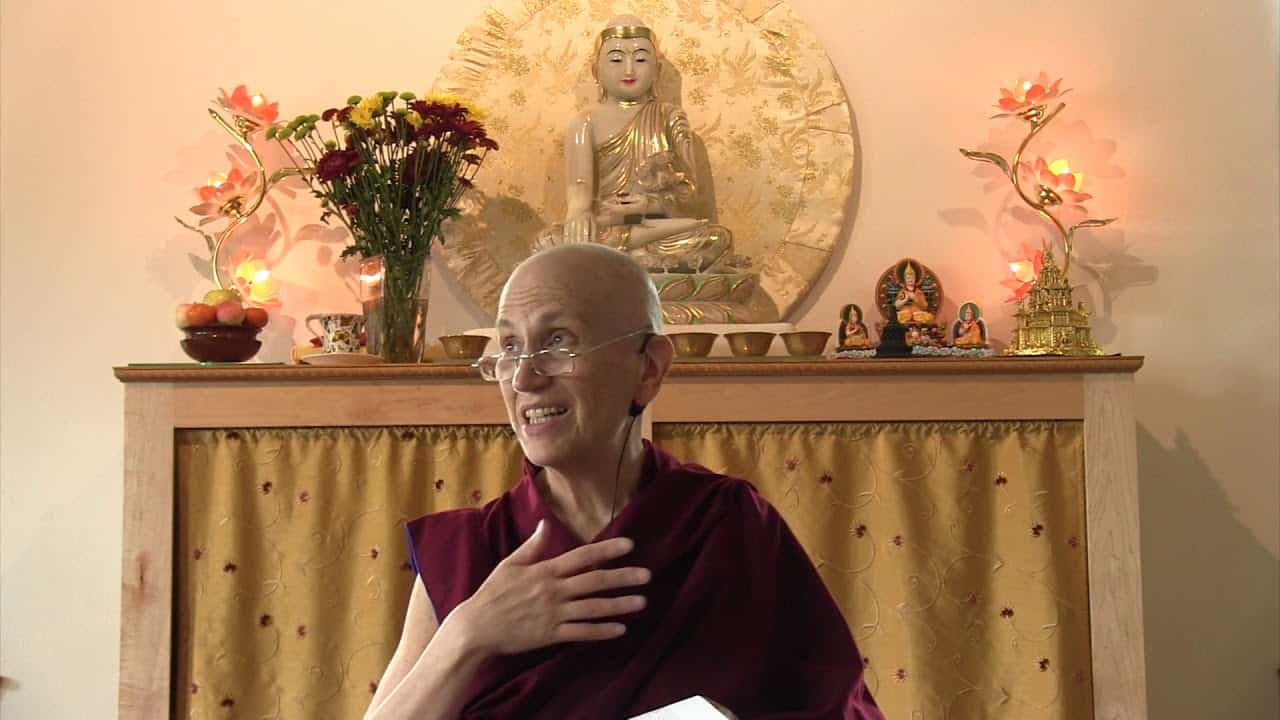

Venerable Thubten Chodron

Venerable Chodron emphasizes the practical application of Buddha’s teachings in our daily lives and is especially skilled at explaining them in ways easily understood and practiced by Westerners. She is well known for her warm, humorous, and lucid teachings. She was ordained as a Buddhist nun in 1977 by Kyabje Ling Rinpoche in Dharamsala, India, and in 1986 she received bhikshuni (full) ordination in Taiwan. Read her full bio.