An inquiry into Master Xuyun’s experiences of long-dwelling in samādhi

An inquiry into Master Xuyun’s experiences of long-dwelling in samādhi

By Huimin Bhikṣu

President, Dharma Drum Buddhist College

Professor, Taipei National University of the Arts

Abstract

According to The Chronicle of Master Xuyun, the Master had three experiences of long dwelling in samādhi—one for eighteen days, and two of nine days’ duration.

Master Xuyun has remarked that his eighteen-day samādhi experience on (Zhungnan mountain (Dec. 1901- Jan. 1902) at the age of 62 was not intentional, as one cannot enter samādhi with such an intention; but neither was it unintentional.

He used the Chan practice of ‘Observing the Head Phrase’ to answer questions about how to enter samādhi, but he did not address the issue of surviving long-dwelling experiences without sustenance.

According to the Abhidharma- mahā-vibhāṣā-śastra, beings in the desire realm require ‘sequential physical food’ to sustain the existence of the bodily elements.

The Cheng weishi lun liaoyideng 成唯 識論了義燈 asserts that when long-dwelling in the ‘concentration of cessation’, life is sustained by the three kinds of spiritual food, namely ‘consciousness’, ‘sensory food’, and ‘volition’.

But both the Abhidharma-mahā-vibhāṣā-śastra and the Tattva-siddhi-śāstra presume the absence of all the four foods (‘sequential physical food’, ‘consciousness’, ‘sensory food’, and ‘volition’) during ‘concentration of cessation’. This article will discuss Master Xuyun’s long-dwelling from an historical perspective and investigate the practical considerations of surviving so long in such a state.

虛雲和尚長時住定經驗之探索

釋惠敏

法鼓佛教學院校長國立台北藝術大學教授

摘要

根據《虛雲和尚年譜》,虛雲和尚一生中有三次(十八、九日、九日)長時「住定」 時間記錄。虛雲和尚談到,1901年底(62歲) 至1902年初(63歲) 在終南山入定十八天不是有 心入定,因為有心一定不能入定;也不是無心入定,並以「看話頭」的禪法,答覆如何入定 的問題。但他沒有提到在此長時間的禪定中沒有飲食卻能維生的問題。根據《大毘婆沙論》 認為,欲界眾生的身體成份(諸根大種)須由飲食養分來維持;而《成唯識論了義燈》討論 長時安住於「滅盡定」時,是以識、觸、思等三種精神性的食物來維持生命。但是《大毘婆 沙論》與《成實論》則認為安住於「滅盡定」者,段、識、觸、思等四種食物皆無。這篇文 章將從歷史的角度及研究維持生命的實際考量,探討虛雲和尚的長時住定經驗。 關鍵字: 虛雲、禪定、四食、彌勒、識智

Foreword

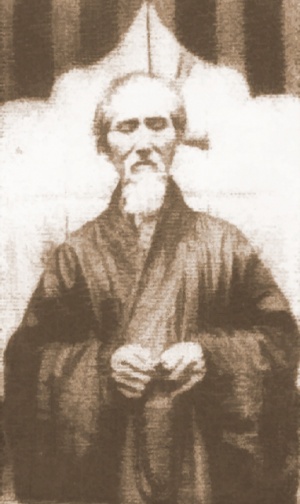

According to The Chronicle of Master Xuyun, (hereafter abbreviated as Chronicle) compiled by Cen Xuelu, Master Xuyun (1840-1959) was born in the city of Xiang in Hunan with the secular name Xiao.

He was fully ordained at the age of 20 by Master Miaolian of Gushan, the Drum Mountain, and was given the ordination names Guyan and Yanche as well as the alias, Dechin.

In fits and starts for six years he practiced the austere life and carried out repentance ceremonies in mountain caves; for four in-between years he took labored in Yongquan temple.

During the ages of 31 to 43 he paid visits to virtuous friends, did physical work, and studied Chan and other Buddhist teachings.

At the age of 43, Xuyun made a resolve to go on a pilgrimage from Putuo Mountain to Wutai Mountain, prostrating himself at each third step, as repayment to his parents’ kindness.

This took three years of hardship to accomplish, in the face of cold weather and deprivation.

From the age of 46 to 48, he lived in a hut in Zhungnan Mountain 終南山 practicing Chan with a few companions.

From the age of 49 to 50, he visited various Buddhist holy sites, traveling through Sechuan, Xikang, Tibet, India, Sri Lanka, Myanmar, and so on.

From 51 to 55, he studied Buddhist doctrines in Jiangsu 江蘇 and at the Cuifeng hut 翠峰茅蓬 of Jiuhua Mountain 九華山, Anhui province 安徽省.

One day in the year 1895 (aged 56) while practicing Chan teachings at Kaomin temple 高旻寺 in Jiangsu province, it is said that he splashed hot water on his hand and dropped his cup.

At that sound, he suddenly awoke from delusion and attained to a kind of enlightenment.

At age 61, he undertook a second pilgrimage journey to Wutai Mountain 五 臺山, then secluded himself in Zhungnan Mountain, at which point he changed his name to Xuyun 虛雲.

From the age of 63 until the end of his life (at the age of 120), the Master traveled throughout Yunnan 雲南, South-East Asia, Fujian 福建, Guangdong 廣東, and Jiangxi 江西 to advocate the protection of Buddhism and the establishment of the sangha, to disseminate and expound Buddhist teachings, invigorate monasteries, and renovate old temples.

He also revived and transmitted the lineages of the five major Chan schools: Caodung 曹洞, Linji 臨濟, Yunmen 雲門, Fayan 法眼, and Wuiyang 溈仰.

His major writings—the Lenyanjin-Xuanyao 楞嚴經玄要, Fahuajin-lueshu 法華經略疏, Yijiaojinzhushe 遺教經註釋, Yuanjuejin-xuanyi 圓覺經玄義, Xinjin-jie 心經解 and others—were all inspired by the Yunmen incident.

A miscellaneous few categories of works—such as dharma talks, doctrinal elucidation, letters, notes, stipulations, verses, and eulogies—were compiled by his disciples into Master Xuyun’s Dharma Collection 虛雲和尚法彙.

During his life, Master Xuyun practiced the compassionate deeds of charity, morality, patience, effort, meditation and wisdom to fulfill self-cultivation inward and conduct propagation of Buddhism outward, all of which no doubt made him a Buddhist paragon.

This rest of this article will discuss some ramifications of one his most renowned and unusual accomplishments: long dwelling in samādhi.

Duration, Method and Experience

According to the Chronicle, Master Xuyun had three experiences of long dwelling in samādhi, the duration and details of which are reported as follows:

1. For a period of 18 days. From the end of 1901 to the beginning of 1902, at the age of 63 the Master,living alone in his hut in Zhongnan mountain.

While sitting cross-legged waiting for his meal of taro to be well cooked, he entered into samādhi and remained therein for half a month.

2. For a period of nine days. In 1907 (age 68), at Thailand’s Longquan Temple, while delivering discourse on Pumenpin (the Universal Gate Chapter of the Lotus Sūtra) following his discourse on Dizang-jing (the Earth Repository Sūtra), the Master entered into samādhi, forgetting about his speech.

He stayed in concentration for nine days, which made a stir in the capital city of Thailand.

The king and ministers as well as ordinary men and women believers all came to pay their worship.

3. For a period of nine days (the Yunmen incident).

In the year 1951 (when the Master was aged 112), the Yunmen Chan temple in Guangdong Qujiang was accused of hiding weapons and treasure.

Twenty-six monks were arrested and tortured. Some were tortured to death or suffered broken bones.

The Master also endured several savage beatings. On the third day of the third lunar month, the Master, now seriously ill, sat crosslegged and entered into samādhi.

He closed his eyes and would not talk, eat, or drink, while only his attendants Fayun and Kuanchun waited on him day and night.

In this manner he stayed in the samādhi for nine days.

From the traditional Buddhist viewpoint, how are such instances of long-dwelling in samādhi possible?

What are the relevant issues for the tradition regarding the study of samādhi?

Are other, similar cases, found in the Buddhist literature?

These issues among others are the focal themes of this article.

Let us first discuss dwelling in samādhi.

Entering, Dwelling in, and Emerging from Samādhi

In Buddhist literature, the development of samādhi is divided into entering, dwelling and emerging.

For example, in the Dazhidu lun (Treatise on the Great Perfection of Wisdom), the samādhi power—one of the five powers of faith, effort, mindfulness, concentration, and wisdom—is defined as:

“the power of concentration which manifests as a bodhisattva being accomplished at perceiving the signs of samādhi, being able to achieve all kinds of samādhis, and having complete understanding of the approaches to samādhi.

He knows well the entering in, dwelling in, and emerging from samādhi, but does not attach to, indulge in, or rely on it.

He knows well the meditative object, knows well when it is ended, freely riding through all samādhis;

he also knows the unconditional samādhi, not to follow others’ opinions.

Not entirely relying on the practice of samādhi, he acts freely without hindrances when in and out of samādhi.

This is named Samādhi Power.”

In the Samāhita Ground chapter of the Yuqieshi di lun, during discussion of meditative objects, the three stages of entering in, dwelling in, and emerging from samādhi are included within the 32 signs (i.e., 32 characteristics of a meditational object).

There, it is described as follows: “What is the sign of entering into samādhi?

It is when, because of the meditated object, one enters into samādhi; or when, samādhi being attained, the object manifests in front.

What is the sign of dwelling in samādhi?

It is when one skillfully takes in those signs. Being skillful in attaining the signs, he tranquilly dwells in samādhi whenever he wishes. And he attains to non-retrogression in the attainment of samādhi.

What is the sign of emerging from samādhi? It is when one cognizes the nonconcentration state that is not involved in samādhi.”

Thus we can see that according to the Samāhita Ground chapter the sign of dwelling-in samādhi is to skillfully grasp the meditative object of samādhi, fully following one’s own will, and to be capable of dwelling in it stably:

this is the attainment of non-retrogression in samādhi.

In the southern branch of Buddhism, the Visuddhimagga (the Path of Purification) describes five kinds of capabilities involved in the development of samādhi regardless of place and time: in terms of entering, dwelling, emerging, turning, and observing.

Long-dwelling on Zhongnan Mountain

From the end of 1901 to the beginning of 1903 (when the Master was aged 63), during the New Year’s festival, Xuyun lived alone in his hut on Zhongnan Mountain.

He unintentionally entered into samādhi and dwelled for 18 days while sitting cross-legged, waiting for his meal of taro to be well-cooked.

The relevant account in the Chronicle states: In the 28th year of emperor Guangxu, Qing dynasty [1901 CE] … near the year’s end, with all mountains heavily covered with snow, and the weather frigidly cold, I lived alone in the hut, pure and serene physically and mentally.

One day while cooking taro and waiting for it to be well-done, sitting cross-legged, I unintentionally entered and dwelled in samādhi.

Guangxu 29th year [1902 CE]: at the beginning of the New Year, I dwelled in samādhi and was not aware of the passage of time.

Fucheng and other Venerables living nearby wondered, for a long time, why I did not show up.

They came to extend their New Year’s greetings, and saw the ground outside the hut full of tiger’s footprints but without any sign of a human.

They entered and saw me in samādhi.

After ringing me to awake, they asked, “Have you eaten or not?” I said: “Not yet.

I guess the taro in the pot is well-cooked now.”

After removing the pot lid, we found mold had grown for more than an inch, frozen and hard as rock.

Fucheng was surprised and said, ‘You have been in samādhi half a month!’

We together heated up snow and cooked taro.

They all ate and left. A couple of days later, monastic and lay people near and far all came to see me.

I was tired of telling them about the event, and therefore left at night quietly.

With bag on shoulder, I left for a place where no inhabitants would be seen within ten thousand miles.

The Chronicle mentions that while Master Xuyun was in samādhi, Venerable Fucheng (who lived in a nearby hut) rang the yinqing, a ceremonial instrument, for the Master to emerge; and remarked that the Master had dwelled for around half a month.

However, after the Master’s passing away, Venerable Chunguo, who was a monastic member of the Gushan temple in Fujian province, wrote A Brief Biographical account of Old Master Yun, a memorial article, in which he mentioned this event’s record of 18 days.

Moreover, in The Grandmaster’s Teachings (included in Master Xuyun’s Dharma Collection), taken down by Venerable Lingyuan—a disciple of Master Xuyun—the account states that Master Xuyun had dwelled in samādhi for 18 days.

A conversation between the grandmaster and the disciple regarding the event was also included as follows:

Q: I heard that Grandmaster had an experience of samādhi for 18 days. Was that an intentional one? Or an unintentional one?

A: One cannot enter samādhi intentionally; but neither can one enter unintentionally as one is not insentient like a stone or statue. Rather, it is concentration that brings success to whatever the mind aims at.

Q: I would like to learn from Grandmaster. Please teach me. A: You must observe the origin of the Head Phrase.

Q: What is the origin of the Head Phrase, please?

A: The phrase is but illusory thought, which you talk to yourself. At the point when the talking is about to arise, watch and observe, see what the original face is like.

That is the what it means ‘to observe the origin of the Head Phrase’.

At the arising of illusory thought, continue to set up your right mindfulness, and the ill thought will subside by itself.

If you have been pulled away by illusory thought, it brings you no benefit to sit meditating.

Even when you are mindful again, but if you are not sincere and earnest, the Head Phrase being weak, the illusory thought will certainly arise.

Therefore you should be brave and diligent in your efforts, as if you had lost your parents.

Learning the Way is like standing guard over a forbidden city, on the wall of which one should be attentive and alert; without going through the season biting cold, the plum tree will not blossom and deliver strong fragrance (these words the Grandmaster would always mention on Chan-week).

Sitting with empty mind, not observing illusory thought and the Head Phrase, is as futile as soaking a stone in cold water: it brings no benefit even if one keeps sitting for eons.

For Chan-practice, once you are determined, the only way is to do it with diligence and effort.

As if one man stood against ten thousand enemies, one should go ahead and never retrogress, taking no opportunity to relax.

It is also applicable to the practice of mindfulness by reciting a Buddha’s name or holding a mantra.

Be earnest to get out of the cycle of birth and death, and work harder and harder day after day.

This way, progress is assured.”

In this account by Venerable Linyuan, two issues related to samādhi are worth further discussion:

- (1) concentration brings success and

- (2) entering into samādhi by way of a head phrase. Let us look at each of these issues in turn.

Concentration Brings Success

Master Xuyun said he did not enter into samādhi and dwell for 18 days intentionally, since samādhi cannot be attained with such intention. Neither did he enter samādhi unintentionally, for one is not as insentient as a statue.

That is, he did it neither intentionally nor unintentionally. Intention or its lack is not the issue: rather, ‘it is concentration that brings success to whatever the mind is determined on.’

The Fo chuiboniepan lueshuo jiaojie jing 佛垂般涅槃略說教誡經(Sūtra of the Summary Instructions Given by the Buddha at the Great Nirvāṇa, also known as Fo yijiao jing 佛遺教 經) states:

“You monks, who are able to abide in precepts, should control the five sense organs, restraining them from involvement in the five desires... Mind is the master of the five organs;

therefore you should control well the mind...subdue it urgently and do not let it get out of control.

One who indulges the mind loses good deeds. Concentrating it at one place brings success to whatsoever is aimed at.

Therefore monks, you should strive in effort and diligence to subdue the mind.”

The original text reads as “One who indulges the mind loses good deeds. Concentrating it at one place brings success to whatsoever is aimed at.”

Later texts cite this passage as, “Concentration of the mind brings success to whatsoever is aimed at.”

The Buddha admonishes his monks to control their five faculties not allow them to indulge in the five desires of form, sound, odor, taste, and touch.

He also points out that the mind is the master of the faculties. Therefore, one should diligently subdue the mind to succeed in one’s

Entering into Samādhi by Way of a Head Phrase

Master Xuyun’s suggested method for entering samādhi is ‘to observe a Head Phrase 話 頭’.

The practice of observing a Head Phrase in meditation originated with Tong dynasty Chan- master Xiyun 希運(? -849) of Huangbo 黃檗 mountain.

Xiyun referred to Zhaozho 趙 州 Chan-master Cungshen’s 從諗(778-897) phrase, ‘Dogs have no buddha-nature,’ as recounted in Huangbo duanji chanshi wanlinglu 黃檗斷際禪師宛陵錄:

One day the master was in the lecture hall. He taught the audience and said: “If you cannot realize it beforehand, when the end of life comes, you will definitely be afflicted. A non-Buddhist sneered when hearing of others’ hard work, doubting all this. I asked, ‘if you were dying all of a sudden, with what would you fight the crisis…?’ Be a man, and observe this case (gong-an): A monk asked master Zhaozho,

‘Do dogs have buddha-nature or not?’ Zho said: ‘No.’ The monk left and observed the word ‘no’ all day long. He observed the word day and night, whether walking, living, sitting, lying down, changing (clothes), eating, or answering calls of nature; taking care of it wholeheartedly with effort and diligence. He observed the word ‘no’ for such a long time that he completely forgot himself, and all of a sudden his mind burst into development and he was enlightened to the essence of Buddhism. No more would he be deceived by the opinions of old masters around the world, and he would dare to say:

The coming of Patriarch Bodhidharma from the west would be just like waves that arise without wind, like the Blessed One picking up a flower but with nothing to prove. A thousand saints will not help, not to mention the King of Hell. He would not believe in the Way that is really so wondrous. And why? The person who makes the resolve will accomplish the task. A verse says: To liberate from the defiled world is no easy thing, and one should hold tight the rope-head and endeavor on it. Without enduring through the season of biting cold, how can the plum tree send out strong fragrance in its blossom?”

Chan-master Huangbo taught his students to concentrate on the word ‘no ‘for a lengthy period of time, until one became fully absorbed in it. At which time one would attain enlightenment and be liberated from the delusions and defilements of birth and death. Huangbo encouraged his students, citing the verse: “To liberate from the defiled world is no easy thing, and one should hold tight the rope-head and endeavor on it. Without enduring through the season biting cold, how can the plum tree send out strong fragrance in its blossom?”

These particular lines were often referred to by Master Xuyun, as can be seen in this remark by Venerable Linyuan: ‘These words the Grandmaster would always mention on Chan-week’ (see above). The same reference here ascribed to Chan-master Huangbo also appears in Master Xuyun’s discourse, Shanghai yufosi chanqi kaishi (Talks During Chanweek at Shanghai Yufo Temple) delivered February 25, 1953, and compiled by Cen Xuelu. Interestingly, the Master changed the first two lines to, ‘Learning the Way is like guarding over a forbidden city, on the wall of which one should be very attentive and alert’, possibly due to the similarity of the pronunciations of rope-head (shento) and city-wall (chento). He interpreted them in this way: “To work hard, we should guard over this phrase as if we were guarding over the forbidden city, so strictly that no one is allowed entry.” The simile of ‘Learning the Way like guarding over a forbidden city’ was also used by Shi Miaopu 釋妙普 in his poem collected in Daming gaosen zhuan 大明高僧傳 and Xu chuandenglu 續傳燈錄: ‘Learning the Way is like guarding over a forbidden city, in the way that one attentively guards against the six thieves day and night. The general in chief, who can send commands, brings peace without arousing a war.’

The citation of Chan-master Zhaozho’s gong-an by master Huangbo teaches meditators ‘to observe the word ‘No’. Chan-master Dahui-zunggao 大慧宗杲(1089-1163) of Song dynasty, in his Dahui pujue chanshi yulu 大慧普覺禪師語錄, also strongly urges meditators ‘to observe the Head Phrase’ until the point where illusory thoughts arise and cease:

At the arising of illusory thoughts, one should not stop the mind, since the thoughts being stopped will become even more active. Just observe the Head Phrase for its arising and ceasing. Even if the Honorable Sākyamuni or the master Dharma came forth again, the answer would remain the same.

A monk once asked Zhaozho: ‘Do dogs have buddha-nature or not?’ Zho said, ‘no.’ All of you like to repeat what others say about the Way, saying that it does not refer to the nothingness as related to somethingness, and that it rather refers to the absolute nothingness that is not equivalent to worldly nihilism. By saying this, can one overcome birth and death or not? If not, it is not the point. Since it is not the point, one should bring it [the Head Phrase) up all the time.

Whether walking or sitting, whether feeling joyful, angry, sorrowful or happy or even when engaged in social activities, always bring it to mind. Bring it this way and that way until it gets dull and as if boiling a ball of hot iron in the mind. That moment is just the right time when one should not give up. Stick to it and all of a sudden the mind will develop and illuminate, shining on realms in all the ten directions. One will then be able to manifest the Treasure-king’s realm on a hair’s tip, and turn the Wheel of Dharma while sitting in a dust mote.

Boiling a Ball of Hot Iron in the Mind

As we have seen, the advice of the Chan masters is that the meditator should always keep the ‘Head Phrase’ in mind. One is advised to consider it this way and that way until it gets dull, and as if one is “boiling a ball of hot iron in the mind.” By “boiling a ball of hot iron in the mind”, Chan master Dahui refers to the state of ‘no discrimination’. He states, “Since one has resolved to fight the sudden and unexpected arrival of death and rebirth, one should straightforwardly aspire for the Utmost Bodhi. As for the illusory things of the world, give them up right away. Just focus at the point where you can neither take nor give, and watch to see whether there is something or not. At the moment when there is no use of mind and speech, when there seems to be a hot ball of iron in the mind, at that moment hold on and observe the origin of the Head Phrase.”

What is the meaning of “boiling a ball of hot iron in the mind”? This phrase would probably be easier to understand if we refer to the simile of “swallowing a hot iron ball” used in Wumenguan (written by Wumen-huikai Chan master in the Song dynasty and compiled by Miyian-zungshao): “Observe the word ‘no’. Bring it to mind day and night, and do not interpret it as nihilism or as nothingness relative to somethingness. As if swallowing down a hot iron ball, which one feels in vain to vomit out, one feels all mistaken cognitions and awarenesses being swept up. Practice for a long time until skillful, and there will be no boundary between the inner mind and the external world. The feeling will be left to oneself like a dumb person’s dream.”

Biting a Raw Iron Bar

On other occasions, the master Dahui compared the state “inaccessible by thought and speech”—reached by constantly bringing up the Head Phrase—to “biting a raw iron bar”. He remarked that, “When getting skillful at considering the Head Phrase—at the point which thought and speech cannot access—the mind being unsettled, it feels as boring as biting a raw iron bar. Do not give up. This moment is actually when the good result will come.” Dahui also said, “In studying the teachings in the Scriptures on how ancient sages entered the Path, the moment when one feels bored and dull as if biting an iron bar is just the point one should focus on. The most important thing is to persevere, for one has reached the place where consciousness fails to work, which thought fails to reach, and where discrimination is cut off and reasoning is destroyed. What one can reason about and where discrimination can be exercised are all but things concerning emotion and consciousness. In those circumstances, one usually takes thieves for sons. This should be well known.”

Like a Conflagration

Chan-master Dahui also offered meditation advise to county magistrate Luo-mengbi: “In daily life, whenever possible, to stay in quietude. When distracting thoughts arise, just bring the Head Phrase to mind, for the Head Phrase is like a conflagration that does not allow mosquitoes or ants to rest upon it. Bring it to mind all the time, dwelling on it at length, and then all of a sudden the mind, having nothing to lean on, will burst into development. At that right moment, there is no need of asking about what is birth, what is death or what is neither-birth-nor-death. No need of asking about who says so, and no need of asking about who hears the saying, either. It is like not wanting to eat when already full.”14 In the above simile, the mosquitoes and ants of Chan-master Dahui refer to ‘distracting thoughts,’ which cannot rest upon a fire.

Master Xuyun spoke to the relationship between ‘Head Phrase’ and ‘distracting thoughts’. He pointed out that, “when the Head Phrase is weak, illusory thoughts will surely arise”, and described the observation of a Head Phrase in three steps:

- (1) understand that the ‘phrase’ is but illusory thought, a speech one talks to oneself,

- (2) watch where the illusory thought is about to arise, and

- (3) observe the original face (true nature). Thus the observation of a Head

Phrase follows three steps.

According to Master Xuyun’s ‘The Prerequisite for Chan Meditation’ (collected in the chapter ‘Teaching’ in Master Xuyun’s Dharma Collection), “Mental speech arises from the mind, so the mind is the origin of speech; thought arises from the mind, so the mind is the origin of thought. The mind gives birth to everything and it is the origin of everything. In fact, the origin of speech is the origin of thought. The place before thought is the mind. To put it straightforwardly, where a thought is not yet to arise is the origin of speech. Thus we know the observation of the origin of speech is the observation of the mind. The original face before our birth is the mind. And to see the original face before our birth is to observe the mind.”

In this statement the Master explains that, ‘the observation of the Head Phrase’ is equivalent to ‘the observation of the mind.’

Nine days Long-dwelling, Aged 68

In the year 1906, when Xuyun was aged 67, the Qing emperor had not yet awarded the ‘Dragon Canon’to the Yunnan area. Master Xuyun consulted with a few supporters to request the emperor for an award of the Canon to Yingxiang temple at Jizu Mountain, Yunnan. Consequently, the Master sailed for Yunnan. Mid-way, he gave a discourse on Pumenpin (the Universal Gate chapter of the Lotus Sūtra) at Longchuen Temple in Thailand.

One day the Master entered into samādhi, sitting cross-legged, abandoning the thread of his speech. He stayed in samādhi for nine days, which caused a stir in the capital city of Thailand. The king and his ministers, as well as ordinary male and female believers, all came to pay their respects. After emerging from samādhi and finishing his lecture, he was invited to the palace for a sūtra recitation ceremony, and there received numerous offerings. The king, ministers and ordinary people asking for Buddhist refuge numbered many thousands.

The Master recounted in the Chronicle that, for more than twenty days after emerging from samādhi, he had the following physical symptoms:

My feet became numb, which initially caused inconvenience in walking and finally a complete paralysis in the whole body. I could not hold chopsticks and relied on others to feed me. Devotees kindly brought doctors for both Chinese and Western treatments but in vain. I could not even talk or see, and all the doctors were at their wit’s end. Nonetheless, I remained calm and clear without feeling any pain, letting go of everything except one matter: I had a money order sealed in my collar that nobody knew about. I was afraid that without being able to talk and write, the money order would be burned at my cremation and the construction of the temple at Jizu Mountain would fail. How could I endure the causal result? I burst into tears (thinking) about that, and prayed silently to Mahākāśyapa for blessing.

At that time Venerable Miaoyuan, who used to live at Zhungnan mountain as I did, seeing me in tears and attempting to talk, leaned forward. I asked him to prepare some tea and to pray for Mahākāśyapa’s blessing. After taking the blessed tea, I felt calm and cool in my mind and had a dream. In the dream I saw an old monk resembling Mahākāśyapa sitting at my side, rubbing my head and saying: ‘Monk! Do keep your robe and bowl close with you. There is no need to worry. Pillow your head on the robe and bowl, and everything will be fine.’

I followed his advice and put my robe and bowl under my head as a pillow. In an instant the Venerable Arhat left my sight. Sweating all over, I felt unspeakably joyful. As soon as I could talk a little, I had Miaoyuan pray to the medicine god Huatuo for a cure. After taking his prescription—mujie and yiemingsha—I was able to see and talk. I prayed for another prescription, which turned out to be just adzuki beans. After taking the cereal made of adzuki beans for two days, I was able to move my head. I prayed again and was still prescribed adzuki beans. From then on I took the beans for food, and later passed stool dark as pitch. Gradually I could feel itching and pain, and I could get up and walk. The treatment lasted for over 20 days.”

The physical impact caused by long-time dwelling in the samādhi can be compared to similar examples in Buddhist literature concerning the ‘concentration of cessation’ (nirodha samāpatti),.although it is not certain that Master Xuyun had cultivated the ‘concentration of cessation’

How Long Can One Dwell in the Concentration of Cessation?

The time one can dwell in the ‘concentration of cessation’ and the physical effects of long-time dwelling in samādhi are discussed in Da piposha lun 大毘婆沙論(Abhidharmamahāvibhāṣā- śastra) :

Q: How long should one dwell in the concentration of cessation?

A: Sentient beings of the Desire Realm rely on physical food for nourishing theelements of their organs. During long dwelling, the body seems not to be harmed in samādhi. However, one collapses physically after emerging from it. Therefore, one should only dwell for a short time, within seven days and nights, due to the exhaustion of nutriment.

The treatise makes the obvious scientific point that beings of the Desire Realm rely on nutriments to sustain their bodies. During long dwelling, though the body appears unharmed while in samādhi, physical collapse occurs following emergence. Therefore one who dwells in the concentration of cessation should not abide beyond seven days and nights due to a dangerous lack of nutriment from physical food. Two examples are given in the treatise for illustration:

Example one: subject dwelled in a concentration of cessation for three months and died at emerging from it. The treatise reports:

It was heard that in a monastery there was a bhikṣu who had attained the samādhi of Cessation. At dinner time, he wore his robe, took his bowl and headed for the dining room. That day dinner was a little late, so the diligent monk thought to himself:

‘Why do I let the time pass without doing any good?’ He thus vowed to enter a concentration of cessation and emerge from it at dinner time. However, a calamity happened to the monastery and all the monks scattered to other places. The calamity was cleared up three months later when all the monks returned to the monastery. At dinner time, the monk emerged from samādhi and died soon after.

Example two: Subject dwelled in concentration of cessation for a half or full month and died at emerging from it. The treatise reports:

Another bhikṣu who had attained the Samādhi of Cessation used to beg for food regularly. One early morning, wearing his robe and bringing his bowl, he was bound for the village, when there was a downpour. Afraid of spoiling his robe, the monk thought to himself: ‘Why do I let the time pass without doing any good?’ He vowed to enter a concentration of cessation and not emerge until it stopped raining. It rained for half a month, or some say an entire month. The monk emerged from samādhi and died.

The situation whereby these two monks decided to make good use of time by entering the samādhi of cessation is reminiscent of Master Xuyun entering unintentionally into samādhi while waiting for his taro to cook, except for the important fact that Master Xuyun did not die.

He almost died in 1907 at Thailand’s Longquan Temple, however, where he suffered from paralysis for more than twenty days after emerging from his samādhi. Therefore the advice given in the Da piposha lun—based on the examples of the two monks who died— that the time for dwelling in samādhi should not last beyond seven days and nights, does not seem an absolute rule. It seems that the dwelling time can be extended, if the dwellers’ physical constitution allows, to nine days or even longer.

Another statement in the [[Da piposha [un]] describes the tolerance to long-dwelling of form-realm beings: “Because the gross elements of the organs need not rely on coarse food for sustenance, sentient beings of the Form Realm can dwell in samādhi for a halfkalpa, a kalpa, or even longer.” According to the tradition, a kalpa is about 16,800 thousand years.

Sustenance for Dwellers in the Samādhi of Cessation

For a meditator long-dwelling in the concentration of cessation, adequate nutrition by taking physical food is impossible. What then does the tradition assert sustains the life of the practitioner? The Cheng wueishilun liaoyideng states:

Q: What does the meditator rely on for sustenance while [long-] dwelling in the samādhi of cessation?

A: Consciousness, touch, and volition.

Consciousness, touch, and volition are the three kinds of spiritual food that sustain and cultivate sentient beings. Here, consciousness refers to the mental consciousness that sustains the fundamental life-functions; this type of consciousness is a composite function of organ and object (e.g., the consciousness of joy or pleasure that arises when the eye beholds a pleasing form).

However, Da piposha lun holds a different view than Cheng wueishilun liaoyideng: Dwelling in ‘the tainted and mind-possessing [i.e., non-cessational] states of concentration’, the meditator—though cut off from physical food—is sustained by tainted touch, volition and consciousness. While dwelling in ‘the concentration of taintlessness’, the meditator though cut off from the four kinds of food, survives on nutriments similar to touch, volition and consciousness. Dwelling in ‘the concentration of cessation’, the meditator is cut off from physical food and spiritual foods of consciousness, touch and volition as well.

The relationship between the three kinds of samādhi and the four kinds of food is shown in the table below:

| Food: samādhi | Physical Food | Tainted Touch, Volition and Consciousness |

Similitude of Touch, Volition and Consciousness |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tainted & Mind-possessing States | No | Yes | |

| Taintlessness | No | No | Yes |

| Cessation | No | No | No |

The Chengshi lun (Treatise on the Establishment of Truth) holds a similar view: “While all living beings are sustained by the four kinds of food, the meditator dwelling in the concentration of cessation does not take any food. Why is it thus said? The meditator does not take physical food. Nor does he take such nutriments as touch and so on (volition, consciousness). So we say he takes no food.”

Another Buddhist legend about how a meditator in the concentration of cessation survives without taking any (physical food) was recounted by Master Xuangzhang after returning from his famous journey to India. On his way home he heard the following tale in Wusha:

Hundreds years ago, a monk was found following a mountain landslide caused by a thunder storm. The man was sitting, his eyes closed, his hair so long as to cover his face and shoulders. The king wondered who this man was, and a monk gave the answer that it was an arhat who had dwelled long in the concentration of cessation. The king asked if there was a way to make him emerge [from concentration). The monk replied that the body [normally] sustained by physical food would collapse on the monk’s emerging. He advised that they first pour cream [into his mouth] to moisten his skin, and then ring a bell in the hope that he might emerge.

The above-mentioned theories and examples concerning how meditators dwelling long in samādhi sustain their bodies might be compared to methods used in modern medical science to sustain the lives of patients in comas or in vegetative states. This is only one of many interesting points of reference to inspire dialogue between the traditions of Buddhism and the practitioners of Life Science.

Nine-days Long-dwelling, Aged 112

In the year 1951, Master Xuyun was aged 112. The Yunmen Chan temple in Guangdong Qujiang was accused of hiding weapons and treasure. Twenty six monks were arrested and tortured. Some were tortured to death or suffered having their arms broken. The Master also endured several savage beatings. On the third day of the third lunar month, the Master, now seriously ill, sat cross-legged and entered into samādhi. He closed his eyes and would not talk, eat, or drink, while only his attendants Fayun and Kuanchun waited on him day and night. In this manner he stayed in samādhi for nine days. The compiler of The Chronicle of Master Xuyun recounts in a supplement how the Master endured his travails through samādhi:

First, on the first day of the third lunar month, they imprisoned the Master separately in a room and locked the door and windows, prohibiting him from eating, passing, or leaving, providing no light, day or night.

The situation was like hell. Then, on the third day of the month, ten husky men entered the room and tried forcing the Master to hand over gold, silver, and weapons. When he denied having such items in his possession, the Master was beaten savagely, first with wooden staves and then with iron rods. They beat him until he bled from his head and face and some of his ribs were broken. They beat him during interrogation, at which time the Master assumed the cross-legged posture and entered into samādhi. Thumping sounds of wooden staves and iron rods could be heard one after another but the Master, eyes closed and keeping silent, appeared to be in samādhi.

That day they beat him four times and tossed him on the floor. Seeing him in danger, they thought he would die. They went out in roars, and all the guards left too. The Master’s attendants waited until nightfall, then helped him to sit on the bed.

On the fifth day of the month, the perpetrators heard that the Master was still alive. They entered the room again and saw the old man sitting properly in samādhi as usual. Angrily, they beat him again with big wooden staves, dragging him to the floor. A dozen people wearing leather shoes kicked him until he bled from the five apertures prostrate on the floor. Thinking he was dead, they left in roars again. At nightfall, the attendants helped the Master to sit on the bed properly as before.

The morning on the tenth day of the month, the Master gradually changed his position to the auspicious reclining posture [like the Buddha at his Parinirvāna), and remained motionless for one day and night. Testing his breathing with a straw to his nose and seeing no movement, the attendants thought the Master had passed away. However, since his body was still warm and his complexion pleasing, the two attendants kept serving him.

Not until the morning of the eleventh day of the month (April 16th), hearing the Master groan slightly, did the attendants help him up. They told him how long he had been in samādhi in his bed, and the Master slowly told his attendants that while in samādhi he travelled to Tuṣita Heaven to hear the Dharma. [He also explained that] in very deep samādhi there is neither pain nor pleasure. In the past, the masters Hanshan and Zibo also experienced the same samādhi state [while being tortured], unconceivable by anyone who has not yet attained samādhi.

During the entire incident, the perpetrators of the violence—having seen the Master’s unusual manifestations—began to wonder and fear. They whispered to one another about it. A man who seemed to be their ringleader asked one of the monks, “why the old guy would not die after such serious beatings?” The monk answered him: “The old Master suffers for living beings’ sake, and for bestowing blessings upon you all. He would not die no matter how bitterly you beat him, which you will realize someday.” The ringleader was so terrified that he did not dare to impose more violence on the Master. However, events had unfolded and their aims were not fulfilled. Fearing that this [embarrassing] news might get out, they continued to besiege and search the temple. All monks were prohibited from talking or leaving, being monitored even during mealtimes, for over a month.

By then his wounds had made the Master so ill that he could not see and could hardly hear. His disciples were afraid that anything unexpected might happen. They urged the Master to recount his biography verbally. These accounts eventually were composed as the Chronicle.

After emerging from the nine-day samādhi, Master Xuyun told his attendants about his experience of visiting the Inner Court of Tuṣita Heaven in a dream, to attend Bodhisattva Maitreya’s teaching of the Dharma:

“I dreamed of paying a visit to the Inner Court of Tuṣita Heaven, the magnificence and beauty of which cannot be found in this world. I saw Bodhisattva Maitreya giving discourse on the dais along with a large assembly of listeners. Among them were more than a dozen acquaintances of mine: namely Master Zhishan of Jiangxi Haihui Temple, Venerable Rongjing of Tiantai Mountain, the Elder Hengzhi of Qishan, Master Baowu of Baisui gong, Master Shengxin of Baohua Mountain, Vinaya Master Duti, Master Guanxin of Jinshan, the Honorable Zibo, and so on. I joined my palms to pay respect, and they showed me to a seat in the third row of the east side. The Honorable Ananda, who led the chanting of the ceremony, sat near me.

In the middle of his lecture on ‘Samādhi of Consciousness-only’, Bodhisattva Maitreya pointed to me and said: ‘You must go back.’ I said: ‘I do not want to go back, as the karmic hindrance on me is deep and heavy.’

Bodhisattva Maitreya said: ‘You have to go back to complete the causation of your life. Come back some other time.’ And he gave me an advisory verse:

Consciousness is not different from wisdom,

As wave and water are but one.

Do not be deceived by the forms of vase and pot,

As the material is exactly the same gold.

By the three natures and three cognitions,

To perceive rope as snake, snail with horns,

Or mistaken reflection of a bow,

Is only because of sickness with delusion.

The body is like a house in dream,

Which is illusory without any substance.

One quits the illusion at the knowledge of it being illusory

And at the quitting from it one thus awakes.

The awakening to the great enlightenment is perfect and illuminating.

The state like a mirror reflecting myriad phenomena

From which are derived sky-flowers, ordinary men and sages,

Good and evil—both are peace and pleasure.

Because of the compassionate vow to save beings

Are these dreamy images made.

Of the unceasing karmic sufferings in the current kalpa,

Vow to warn and cause all to awake.

Sailing with loving-kindness in the bitter sea,

Do not think of retrogressing.

The lotus flower emerges from the muddy water

And the Buddha will be seen to sit erect on it.

There were more sentences, but I do not remember well. Also other advice I will not tell you now.”

In the supplementary account in the Chronicle, the experience of Master Xuyun’s visit in samādhi to Tuṣita Heaven during his torture is compared to the experiences of Hanshan and Zibo. These men, when tortured, also gave up both pain and pleasure while dwelling in deep concentration. According to Qian qianyi’s Daming haiyin hanshandashi lushan wurufeng taming 大明海印憨山大師廬山五乳峰塔銘, Master Hanshan, ‘when tortured during interrogation, entered into samādhi promptly and bore the whipping and burning as if he were a piece of wood or rock.’

While the Zibo laoren ji 紫柏老人集 relates that Master Zibo, ‘during interrogation, endured those tortures with an old and weak body, which made all his attendants brokenhearted. But the Master seemed as peaceful as leisurely-floating cloud and calm water.’

These examples demonstrate how (according to the traditional accounts) the great Masters manifested their samādhi states under political persecution.

Dreaming of Tuṣita Heaven

Bodhisattva Maitreya is known to Buddhists as the future Buddha, presently preaching the Dharma in Tuṣita Heaven. Various examples of entering into samādhi and arising in Tuṣita Heaven to hear Maitreya teach Dharma can be found in the literature. For instance, Master Xuanzhang, in his Datang xiyuji 大唐西域記, recounts an event that took place in Ayodhyā, in central India.

Five or six miles to the southwest of the capital city, in a woods of mango trees, there is an old monastery. This was where Bodhisattva Asaṅga asked for advice to guide sentient beings. At night, Bodhisattva Asaṅga ascended to Heaven and received such treaties as Yogācāra-bhūmi, Mahāyāna-sūtrālaṃkāra, Madhyānta-vibhāga, and so on; by day he preached these wondrous doctrines to the assembly.”

Moreover, quite a few accounts are found in the literature concerning meditators in the countries of Kashmir and India in the 4th and 5th centuries, who also ascended to Tuṣita Heaven in samādhi to beg doctrines from bodhisattva Maitreya. Some examples can be found in The Biographies of Eminent Monks

Buddhabhadra (Juexian 覺賢) was learned and accomplished in the Scriptures, and famous for his mastery of mediation and Vinaya teachings at an early age. He often paid visits to Kashmir along with his colleague Saṃghadatta, and they stayed together for years. Although Saṃghadatta admired Buddhabhadra for his talent and knowledge, he had not yet verified his attainment. One day, while sitting in meditation in a secluded room, he saw Buddhabhadra enter and asked in surprise why he was there. Buddhabhadra answered: ‘I entered Tuṣita Heaven for the moment, to pay homage to the bodhisattva Maitreya.’ He faded away after saying that.’

Another account is about Venerable Zhiyan 智嚴, who traveled far to Kashmir to engage Buddhabhadra to teach the Dharma in China. The text states that “prior to renunciation, (Zhiyan) had received the Five Precepts and committed offenses once in a while. Then after receiving the Full Precepts, he often doubted and worried that he had not have obtained the essence of the precepts. Even with years of practice in meditation he was still unable to determine it by himself. Hence he went overseas again to Tianzhu (India) to consult learned masters. He encountered the venerable arhat and asked him about the matter. The arhat was not certain of the answer. He entered into samādhi for Zhiyan and ascended to Tuṣita Heaven to consult Maitreya. Maitreya replied: ‘Yes, he obtained [the essence of the precepts).’ Zhiyan was so pleased that he walked back to Kashmir and, although not ill, passed away. At that time he was seventy-eight.

Another account: Shi huilan 釋慧覽, worldly name Cheng, hailed from Jiuquan. Like Xuangao 玄高, he was famous for his achievement in the practice of meditation at an early age. Shi huilan visited the western land in search of the Dharma, and acquired the essentials for meditation from the monk Dharma. Dharma entered into samādhi and ascended to Tuṣita Heaven to receive the Bodhisattva Precepts from Maitreya, then imparted them to Shi huilan. Shi huilan journeyed to Yutian to impart the precepts to the local monks and then returned home.

Master Xuyun’s Verses

According to the legend, the Bodhisattva Maitreya bestowed dharma verses on Master Xuyun during the Master’s visit to the Inner Court of Tuṣita Heaven. Analysis of these verses yields the following points:

1. ‘Consciousness is not different from wisdom, as wave and water are but one; Do not be deceived by the forms of vase and pot, as the material is exactly the same gold.’

These lines discuss the relationship between ‘consciousness and wisdom’, comparing them to ‘wave and water’, which are the same in nature. ‘Consciousness and wisdom’ are also compared to vase and pot, both of which use the same material (denoting the same nature). The theme here is similar to a teaching in the Zungjing lu 宗鏡錄: ‘If Suchness does not maintain its self-nature when [undergoing the] transformations of consciousness, it will go with the conditions of the eight consciousnesses. ...For the unchanged nature always goes [unchanged] with every condition, and all conditional phenomena will remain unchanged in their nature, just as the water that generates the waves and the waves derived from the water, both of which are the same in their nature of moisture, although one stirs and the other remains still.”

Citing a verse in Miyan jing 密嚴經(the Ghanavyūha Sūtra), a passage in Qingliang ji 清 涼記states: “The pure Tathāgatagarbha is the worldly ālaya, just like the gold and the ring that have no difference after all. That means the essence of ālaya is the tathāgatagarbha itself.

When tainted by deluded thoughts, it is called ālaya, which has no other self. Likewise, the golden ring is still the gold in essence.”

2. ‘By the three natures and three cognitions, to perceive rope as snake, [anything small like] the snail’s tentacles, or the mistaken reflection of the bow, is only due to the sickness of delusion.’

This passage may refer to the line in Bashi guiju sung 八識規矩頌(Verses on the Structure of the Eight Consciousnesses): ‘Three natures, three cognitions correspond to the three realms’ illustrates that the sixth consciousness is universally involved in the three natures of moral qualities (good, evil, and neutral), three types of valid cognition (direct cognition, inferred cognition, and cognition through teachings of sages) and three object realms (of true manifestation, subjective manifestation and related manifestation).

The ‘rope’ here may refer to the simile in She dasheng lunshi 攝大乘論釋 (Mahāyāna - saṃgaraha-bhāṣya): In the dark a rope manifests seemingly as a snake, by the simile of which the correspondence to the three kinds of nature is held true.31 Accordingly, ‘the three natures’ in the above-mentioned sentence ‘by the three natures and three cognitions’ should be understood as the nature of existence produced from attachment to illusory discrimination (parikalpita), the nature of existence arising from causes and conditions (paratantra), and the nature of existence being perfectly accomplished (pariniṣpanna).

‘[...anything small like] the snail’s tentacles’ is probably cited from the story in Zhuangzi 莊子: ‘A country at the left snail-tentacle named Chushi and the other country at the right tentacle named Manshi often fight each other for the occupation of the land.’ To ‘mistake the reflection of the bow’ refers to the Chinese story known as ‘Sea- Serpent’s Image in Wine Cup, Atmosphere of Fear and Admonition’.

Some usages of the same simile can also be found in Hungzhi chanshi guanglu 宏智禪 師廣錄, namely, ‘A second meditation free of suspicion and the reflection of the bow shows in the cup.’ And ‘Under deluded thought, a rock may be mistaken as a tiger at the hill’s foot. After enlightened, one realizes the reflection of the bow was mistaken as a snake in the wine. No matter how cold or dry, just keep on straightforwardly practicing, for the buddhaseed to sprout from now on.’

3. ‘The body is like a house in a dream, which is illusory without any attachment. One quits the illusion at the knowledge of it being illusory; and at the quitting from it one thus awakes.’

This passage is probably a citation from Yuanjue jing zhuangzi 圓覺經講記(Commetary on the Complete Enlightenment Sūtra): ‘Good sons, at the knowledge of it being illusory one quits the illusion, without need of expedients. At the quitting from illusion one thus awakes, without any sequence.’

4. ‘The awakening to the great enlightenment is perfect and illuminating, the state like a mirror reflecting myriad phenomena. From which are derived sky-flowers, ordinary men and sages, Good and evil: both are peace and pleasure.’

These lines are also related to a teaching in the Complete Enlightenment Sūtra: “Good sons, as all the illusions and transformations of all beings arise from the complete and enlightened wondrous mind of the Tathāgata, so are the sky-flowers derived from the sky. Though the illusory flowers may fade out, the nature of emptiness will not be destroyed. The illusory minds of sentient beings will eventually turn to cessation. After all the illusions have ceased, the enlightened mind remains undisturbed.”

5. ‘Because of the compassionate vow to save the beings, these dreamy images are made.

Vow to warn beings of the unceasing karmic sufferings in the current kalpa, and cause all to awake. Sail with loving-kindness in the bitter sea. Do not think of retrogressing. The lotus flower emerges from the muddy water, and the Buddha will be seen to sit erect on it.’

This passage is meant to encourage meditators to assist their compassionate vows of saving sentient beings and never to retrogress in spite of the karmic hardship and difficulties of the degenerate era. Thus, samādhi is not only for meditators to develop inner peace, as in the sarcastic phrase, ‘taochan’ 逃禪(Chan getaway), but also to generate spiritual strength to establish the pure land on Earth.

Therefore, in his later life (ages 63 to 120 years), for the purpose of establish temples and settling the sangha, Master Xuyun revived six sangha gatherings and reconstructed more than 80 monasteries and nunneries. In the decline of Buddhism and a chaotic world, he stood as a tower of strength.

His life serves the Buddhist tradition as an example of displaying the power of samādhi to rectify and benefit this sorrowful world. Just as importantly, his spirit of ‘getting stronger in old age’ can inspire ‘senior citizens’ to arrange a second career, so crucial to a society faced with an aging population.

Abbreviations

T Taisho Tripitaka. Tokyo: Daizo Shuppansha.

X Shinsan Dainihon Zokuzokyo. Tokyo: Kokusho Kankokai.

References

- Citations from the Taisho Tripitaka and Shinsan Dainihon Zokuzokyo taken from CD 2008 version of Chinese Buddhist Electronic Text Association (CBETA)

- Citations from Master Xuyun’s collection comes from On-line Collection of Master Xuyun 虛雲老和尚網路專集 http://www.bfnn.org/hsuyun.

- Cen Xuelu 岑學呂. 1953. Master Xuyun’s Dharma Collection 虛雲和尚法彙.

- Cen Xuelu 岑學呂. 1978. The Chronicle of Master Xuyun 虛雲和尚年譜. Taipei: Buddhist Publisher 佛教書局.

- Cen Xuelu 岑學呂. 1987. The Chronicle of Master Xuyun and his Dharma Collection 虛 雲和尚年譜暨法彙. Taipei: Buddhist Publisher 佛教書局.

- Ven. Chunguo 純果. 1976. A Brief Biographical Account of Old Master Yun 虛雲老和尚 見聞事略.

- Yinshun 印順. 1968. A Study of Śastras and Śastra-masters Belonging Primarily to the

- Sarvāstivāda 說一切有部為主的論書與論師之研究. Taipei: Zhengwen Publisher.

- Huimin Bhikṣu. 2003. The Characteristic of Buddhist Meditation From the Three Kinds of Meditative Objects in Liumen Jiaoshou Xiding Lun 六門教授習定論. Religious Studies

- 6:117-134. Taipei: Department of Religious Studies, FJCU.

Source

Chung-Hwa Buddhist Journal (2009, 22:45-68) Taipei: Chung-Hwa Institute of Buddhist Studies

中華佛學學報第二十二期頁45-68 (民國九十八年),臺北:中華佛學研究所

ISSN:1017-7132

chibs.edu.tw