Buddha Nature and Zen : Origin and Representation in Japanese Architecture by Prof. Wong Wah Sang

Buddha Nature and Zen :

re

By

Prof. Wong Wah Sang

Associate Professor, Department of Architecture and Centre of Buddhist Studies in the University of Hong Kong

Abstract

This presentation paper discusses the theory of Buddha nature and Zen Buddhism in Japan through a concise historical highlight. The initial dissemination of Buddhism in Japan with introduction of forms of Buddhist architecture was in the sixth and seventh centuries in the days of Prince Shōtoku. At that time the philosophy of Buddha nature (which is called Tathagatagarbha in Sanskrit) was introduced. Afterwards the focus of Buddhism was on Mahayana teaching and esoteric practices under the Japanese Buddhist masters of Saicho and Kukai in the eighth century with the dissemination of Zen Buddhism continued in low profile. Subsequently in the twelve century at the Kamakura period of Japan, an important Zen master, Eisai, brought the Zen teaching into the Shogunate government. The simple way of Zen practices and its adoption into the spirituality of everyday lives enhances the popularity of the teaching for centuries. Japanese traditional temples, tearooms and landscape gardens were representations in the meaning of Buddha Nature.

Key words : Tathagatagarbha, Buddha nature, Zen, Japanese architecture, Japanese gardens

Early dissemination of Buddha Nature in Japan

There is both theory and practice in Buddhism. Like the two sides of a hand, the palm and back, theory and practice are inseparable to form comprehensive understanding or complete realization. This can be illustrated from the introduction of Buddhism to Japan. The native religion of early Japan was Shinto as represented by Shinto Shrines. (Fig. 1) This has been deeply rooted in the early cultures of Japanese people until the arrival of Buddhism. The first formal and important dissemination was in the Asuku Period (538-710CE) and lay in the hands of Prince Shōtoku[1] (572CE to 622CE) when Buddhism was subsequently adopted as the state religion of Japan. At the same time, a Japanese Monk named Dōshō[2] learned Zen Buddhism from China and started teaching in Nara. The Prince taught on the theory of Tathagatagarbha and Dōshō gave the practice on Zen Buddhism.

Two artefacts from traditional Japanese architecture represent the first dissemination of practice and theory of Buddhism in Japan. The Zen practice can be represented by the first meditation hall built in Nara and named as the Gangoji Temple (fig.2) while the lectures of Prince Shōtoku is apparently symbolized by the Aizendo Hall (fig.3) at Shōmaninaizen-dō[3] of Osaka. Yet these two, the theory and practice, are of same origin and essence.

Prince Shōtoku is the author of the Sangyō Gisho which means the “Annotated Commentaries on the Three Sutras”. These three Sutras are the Lotus Sutra, the Vimalakirti Sutra and the Sri Mala Sutra. The Lotus Sutra is a teaching to lead Hinayana disciples into Mahayana, stating that the two vehicles in Hinayana[4] is not ultimate. The Vimalakirti Sutra tells the experience of Vimalakirti, an enlightened person practicing esoteric Buddhism and Zen meditation in the days of Buddha Shakyamuni. The inconceivable state of realization and the dharma of non-duality[5] are mentioned here. Hence we can see both Sutras point to the ultimate wisdom of the Buddha. This realization wisdom is expressed as the wisdom of the Tathagatagarbha in the Sri Mala Sutra. The term Tathagatagarbha has been commonly translated as the Buddha nature or Busshō (佛性) which is the centrality of teaching in schools[6] of Zen Buddhism. To perceive this nature through practices is the objective of Zen. This essence common among Sutras and Zen is thus apparent.

In the Commentary on the Sri Mala Sutra, Prince Shōtoku explains the essential unity of the Dharmakaya[7] (Dharma body) and the Tathagatagarbha has been addressed in the Sutra. The explanation in the Sutra[8] is that “the Dharmakaya of the Tathagata is called Tathagatagarbha when it is not separate from the stores of afflictions.” The essence of the two terms is the same except when specifically stated to be associated with afflictions or the entanglement of defilements. So what is afflictions? Afflictions are the conceptuality arisen in this conventional world caused by notions and interpretations which have been expedient means for human everyday living but at the same time they form obstruction to the natural original reality.

A modern metaphor quoted by Master Tam Shek-Wing is the analogy with the TV screen and the TV images[9]. The TV screen is itself inconceivable yet can only be seen with the TV images. The TV screen denotes the Dharmakaya while the TV images are the conventional world filled with stores of afflictions. These afflictions arise from our common consciousness while the Dharmakaya is the state of Buddha’s self-inner realization wisdom. Here are two issues on the way and goal of realization. As the Dharmakaya is not separate from afflictions, we have a way of realization to start from the afflictions. Yet this Dharmakaya is an inconceivable state, not an entity, but a pure state of experience not contaminated by afflictions like the TV screen so we have a clear goal of realization.

To explain Tathagatagarbha as Buddha nature is to emphasize the potentiality of awareness that resides naturally in human beings. However, this reality of Buddha nature is a hidden potential inside us that can only be discovered through worldly things. Hence in Zen one actually starts to practice with everyday matters or the ordinary mind until one can experience the secret meaning hidden beyond worldly phenomenon. This principle of Zen practice is called understanding the mind to see the original nature. When this is applied to the everyday life, it is like looking at the shadows of bamboo leaves to know the presence of bamboo. This is evident in aesthetics[10] of Japanese culture.

A legend about the Prince meeting Bodhidharma[11] unites the Buddhism theory and Zen practice as with same origin and essence. Bodhidharma appeared and disguised as a starving beggar. Then the Prince gave him food and his purple garment. But the next day the beggar was found dead so the Prince ordered to bury him. Later the Prince discovered the dead body was gone with the soil for burial undisturbed and only the Prince’s garment left. This event was commemorated by the building of the Darumaji Temple (fig.4) in Ōji Town, Nara Prefecture with the main hall located on the position of the tomb.

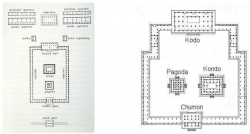

The Buddhist temples commissioned by Prince Shōtoku include the Shitennō-ji (592CE) in Osaka and the Hōryū-ji (607CE) in Nara (fig.5). The Shitennō-ji[12] as the temple for four heavenly gods was laid out in the symmetrical axial order following the Chinese tradition. However, the Hōryū-ji[13] as the temple for flourishing the Buddha’s teaching was designed to jump out of the symmetrical Chinese axial order as a symbol of Japanese culture. Hence, when one enters the main entrance one will find the main hall (kondo) on the right and the five-story pagoda on the left. This marks the distinct identity of Japanese art not restricted by the strong discipline from China.

One of the key feature in the traditional temple layout is the pagoda which stores the relics of the Buddha hence it is a representation of the presence of the Buddha. The original architectural form in India is the stupa[14] which is a half-sphere heap of earth with relics of the Buddha hidden inside and non-accessible. It bears the essential meaning of Buddha nature which is a hidden potential. However, this form of architecture has not been transmitted to China but the function of keeping the Buddha’s relics rests in the pagoda, an architectural form already existing at that time. The pagoda is a building which one can go inside and worship the relics. Thus the implied meaning of Buddha nature is not apparent in the pagoda which can be interpreted as the adaptation of the essential function to local cultural identities. However, many of the pagodas in Japan had been elegantly designed and preserved as symbol of traditional art. For example, the Yakushi-ji[15] (fig.6) in Nara was described by Ernest Fenellosa as “frozen music”.

The theory of Tathagatagarbha or Buddha nature though elucidated by Prince Shōtoku was a profound knowledge difficult to comprehend at that time. Soon after the Prince’s time, the focus of Buddhist teaching was on Mahayana teaching and esoteric practices under the Japanese masters of Saicho and Kukai in the eighth century. As such, the schools of Kegon, Hosso, Shingon and Tendai[16] were powerful in these days. On the other hand, Zen practices did not flourish much. There were occasions when Chinese monks travelled to Japanese soil to plant the seeds of Zen yet there were few fruits ripened. At the twelfth century, common people led a desperate life with frequent internal warfare and sufferings. The Amida (Pure Land) school preached the Lotus Sutra and gave hope for people. Soon, the rising class of warriors found the Zen teaching with its simple and direct teaching compatible with the way of warriors. This is the background for the rise of Zen in the centuries that followed.

Revival and Flourishing of Zen

The Kamakura Period (1185-1333) sees the establishment of shogunate that is the emergence of the class of warriors known as samurai in Japan. The shogun or general is the protector of the emperor and has the utmost power. At that time the Zen theories and practices of Zen master Eisai (1141-1215) was welcomed by the shogunate government. Determined to learn the authentic teaching from India, Eisai travelled twice to China and learned Zen under the Rinzai School master, Hsu-an Huai-ch‘ang[17], whom he obtained the lineage of Zen. He came back to Japan and wrote the work Kōzen Gokokuron (興禅護国論) or “Treatise for Promoting Zen for the Protection of the Nation” (1198) which emphasized on the moral discipline of the clergy to lead the country.

Why did the samurai affiliate with Zen? Zen is a special teaching beyond the scriptures. It started at Sakyamuni’s time when the Buddha was fiddling with a flower rather than teaching in his routine lectures yet only the disciple Kāśyapa responded with a smile. This is transmission of secret meaning from mind to mind. From a functional point of view, Zen[18] is thus a religion of will power which precisely is required by the samurai as the military mind. In the moral discipline, the Zen mind based on the training of focus onto objects will not look backward and philosophically also treat life and death as equal. Such qualities from Zen allowed a close relationship with the samurai.

Eisai founded the Kennin-ji Temple (fig.7) (1202) in Kyoto not only for Zen but for Tendai and Shingon as well. Eisai accepted and acknowledged the harmony for the different schools. As quoted by the Japanese Buddhist scholar, Suzuki, “The Tendai is for the Royal Family, the Shingon for the nobility, the Zen for the warrior classes and the Jōdō for the masses”. It is until the eleventh abbot, Lanxi Daolong (1213-1278) that Kennin-ji became a pure Zen institution.

Though destroyed by fire and re-built a few times, the Kennin-ji Temple[19] still contains quality architecture and Japanese Zen gardens[20]. The latter are set like koans or case studies for the practitioner to realize the meaning of Zen. The Chouontei or the garden of the Sound of the Tide (fig.8) contains the san-zon-seki, a display of three stones representing the Buddha and two monks in meditation and the zazen-seki, a flat stone for seated meditation. Maples are planted to change colours with seasons. This is an appreciation of the power of Dharmakaya to embrace changing forms of life which is the quality of vitality present everywhere. The stones representing the sages stand for the unchanging Buddha nature or the reality of Dharmakaya. Whatever happens to worldly things, the Buddha nature are unchanged.

There is another Zen garden (fig.9) named after Sengai Gibon’s[21] painting of a circle, a square and a triangle. The idea is that all things in the universe are included and represented by the three forms. A well stands in the garden. It is covered by a square mat. There is water hidden underneath. Some people are aware of this while others have no awareness. This is the “square” representing our conventional world. The well water as the source of life is the vitality form the power of the Dharmakaya. This is only known to some people. The dry sand forming circular pattern is the “circle”. This is the path of practices or cultivation to reach reality. The sand is ploughed and shaped as it is ploughed. It is the way to the natural wisdom-as-such. In the center of the circle rises the small tree which nourishes from the ground water and grows without obstruction. This is the “triangle” of complete enlightenment.

Triangle has three sides equal. Hence, in Mahayana teaching, enlightenment is achieved when the three doors of liberation[22] are simultaneously entered, the three kayas[23] are realized indifferently or simply the actualization of the non-conceptuality of the three aspects of nature, appearance and function. The tree represents the worldly phenomena inseparable from the Dharmakaya. This is the wisdom of Tathagatagarbha or Buddha nature.

Another feature in Kennin-ji Temple is the Heiseinochaen which is the tea garden and contains a stone tablet with inscription of tea and the name of Zen master Eisai who is also associated with the cultivation of tea in Japan. The tea seeds he brought back from China was planted in the temple grounds. He also wrote on the benefits of tea drinking. About half a century later, Dai-o (1236-1308) from the Rinzai School of Zen learned the tea ritual in China. There were several monks who subsequently became tea masters[24]. Then Ikkyu (1394-1481) taught the technique to Shuko (1422-1502) who adapted the tea to Japanese taste and soon Sen no Rikyu (1522-1591) completed the cha-no-yu or tea ceremony and designed the chashitsu or tearoom.

The art of tea is based on the spirit of “harmony (wa), reverence (kei), purity (sei) and tranquility (jaku)”[25]. “Harmony” especially refers to the construction of the tearoom (fig.10) from the blending of heaven and earth to establish universal peace. The tearoom is a simple small room in a bamboo grove or underneath trees. There is no furniture inside except the utensils to make the tea ritual. At the tokonoma (alcove), there is a scroll of painting or calligraphy and maybe also a flower arrangement. The wood, straw, paper etc to make the room is indifferent with the trees in nature. The boiling water in the kettle is indifferent with the stream in nature. The flower in the tokonoma is indifferent with flowers outside the tearoom. This harmony with nature arises from the equanimity of vitality everywhere. This vitality is the power of the Dharmakaya.

“Reverence” is experienced when one put down one’s self ego, free from self-importance to see and respect everything around one as the power of Dharmakaya to embrace all phenomena and life. The scroll may carry words like “To learn Buddhism with sincerity” or “All phenomena are embraced in unity” as a reminder to the attendants of the tea ritual.

To attain “Purity” is to be free from the afflictions which are the notions and interpretations leading to conceptuality in daily life. Hence the tea ritual is just boiling water, preparing tea and sipping tea without any intrusion from other worldly matters. Rikyu has written on his mental state in the tearoom:

“The snow-covered mountain path

Winding through the rocks

Has come to its end;

Here stands a hut,

The master is all alone;

No visitors he has,

Nor are any expected.”

This is a state of solitude in Zen meditation to abide in non-conceptuality.

“Tranquility”[26] is the fruition of the Zen practice through the tea ritual. The Vimalakirti Sutra[27] describes Vimalakirti:

“Free of worldly attachments, like the lotus blossom,

Constantly you move within the realm of empty tranquility;

You have mastered the marks of all phenomena, no blocks or hindrances;

Like the sky, you lean on nothing – we bow our heads”

When one attain this state of mind, it is the fundamental non-conceptual wisdom together with the subsequent acquired wisdom. This is the Dharmakaya together with worldly things – the wisdom of Tathagatagarbha or Buddha nature. Zen text says, “To be tranquil yet illuminating and to illuminate yet in tranquility”. From the previous metaphor, tranquility is the original unchanging nature of the TV screen and its power to manifest TV images is the illumination. The TV screen and its power are inseparable. This is the ultimate non-duality.

Epilogue

Zen master Eisai started to revive Buddhism especially through Zen practices. After his time, another great master Dōgen (1200-1253) studied in Kenninji Temple and traveled to learn from China. He founded the Sōtō School of Zen in Japan and had extensive writings on practices and enlightenment throwing light on the understanding of Buddha nature. The Eihei-ji temple he founded remains one of the head temples of Sōtō School today.

Another great Zen master was Hakuin (1685-1768) who revived the Rinzai School with traditional Zen meditation and koan studies. With deep compassion and commitment to benefit others, Hakuin taught Zen practices and wrote on satori or state of realization experience. He was also recognized as one of Japan’s greatest painter though he started to paint only at the age of sixty.

Then with the Meiji Restoration in 1868, the new government adopted a strong anti-Buddhist attitude to eradicate Buddhism as it bears a strong connection to the previous Shoguns. However, the spirit of Zen in the form of simplicity and anti-materialism still persist as an important identity of modern Japanese living (fig.11) while images of tradition in various forms of activities (fig.12) appear now and then in the Japanese cultural calendar.

Footnotes

- ↑ Early Japan adopted the religion of Shinto until Prince Shotoku introduced Buddhism to raise the level of Japanese culture providing people with spiritual fulfilment. Reference : Yoshiro Tamura, 2000, Japanese Buddhism: A Cultural History, Kosei Publishing Co., pg. 29-30.

- ↑ The Japanese monk, Dosho, learned Yogacara and Zen Buddhism in China (653CE) and subsequently disseminated to Japan. Reference : Dumonlin, 1963, “A History of Zen Buddhism”, Munshirim Manoharlal Publishers, pg.138.

- ↑ The Shōmaninaizen-dō literally means the college of “Sri Mala” which refers to the Sri Mala Sutra that the Prince was teaching.

- ↑ The two vehicles teaching the four truths, the twelve links of dependent origination and the principle of emptiness are only expedient means. The One Vehicle of the Buddha as stated in the lotus Sutra is the ultimate teaching.

- ↑ Duality is a view in our conventional world to see things from a reference point, hence things are compared so we have black and white, good and bad etc. Non-duality is to go beyond this constraint. In the Vimalakirti Sutra, Bodhisattvas took turns to explain their realization of non-duality. When it was Vimalakirti’s turn, he just remained silence and was admired by all the Bodhisattvas. It was a demonstration to be free from all notions and interpretations. The Vimalakirti Sutra was also an important text for the Zen School.

- ↑ Bodhidharma, the Indian Buddhist monk who brought Zen to China, said that “Whoever sees his nature is a Buddha; whoever doesn’t is a mortal.” (Reference: Red Pine, The Zen Teaching of Bodhidharma, 1987, North Point Press, pg.17.) The Rinzai School emphasizes on Kensho which means insight into one’s nature. The Soto School bases on Zazen (sitting meditation) to experience Buddha nature.

- ↑ Dharmakaya is the ultimate base of the Buddha to manifest other form-bodies.

- ↑ Reference ; BDK English Tripitaka, 2011 : Prince Shotoku’s Commentary on the Sri Mala Sutra, BDK America, pg. 108.

- ↑ Master Tam explained the power of the Dharmakaya is the embracing cause to arise all worldly things. It is not like a creator to make all living beings but rather like the screen of TV to allow the TV images to appear. Reference : Tam Shek-wing, 2010, Elucidating Tathagatagarbha, All Buddha Press (Taiwan)(published in Chinese), pg. 23.

- ↑ This is called yugen in Japanese aesthetics.

- ↑ Bodhidharma is known as Dharuma in Japan. Legend said that he did not return to India after his trip to China but went on to Japan and this beggar might be his reincarnation or emanated body.

- ↑ Reference: Kakichi Suzuki, 1980, Early Buddhist Architecture in Japan, Kodansha, pg. 48-49.

- ↑ Reference: Kakichi Suzuki, 1980, Early Buddhist Architecture in Japan, Kodansha, pg. 54-57.

- ↑ Reference: Wong Wah Sang, 2014, Stupa, Pagoda and Chorten – Origin and Meaning of Buddhist architecture, 4th Annual International Conference on Architecture, Athens Institute for Education and Research

- ↑ The Yakushi-ji was constructed in three stories with double-roofs that form a progressive rhythmical progression in the skyline. Reference: Kakichi Suzuki, 1980, Early Buddhist Architecture in Japan, Kodansha, pg. 89-92.

- ↑ Reference: Dumolin, 2008, Zen Buddhism: A History Volume 2 Japan, Motilal Banarsidass Publishers, pg. 6-7.

- ↑ Reference: Dumolin, 2008, Zen Buddhism: A History Volume 2 Japan, Motilal Banarsidass Publishers, pg.15.

- ↑ Reference: D.T.Suzuki, 1959, Zen and Japanese Culture, Princeton University Press, pg. 61-63.

- ↑ Online reference : http://www.kenninji.jp/english/

- ↑ Reference: Wong Wah Sang, 2013 “Seeing the Buddha Nature in Japanese Zen Gardens” , International Journal of Business, Humanities and Social Science, Vol. 1, No. 4, Jan 2013. pp. 314-320 , Vol1. no.4, 3140322

- ↑ Sengai Gibon (1750-1837) was a monk of the Rinzai School of Zen Buddhism in Japan.

- ↑ The three doors of liberation are the door of emptiness, the door without appearance and the door without aspiration.

- ↑ The three kayas are the Dharmakaya, the Sambhogakaya and the Nirmanakaya. The first kaya is the inconceivable state of Buddha’s wisdom while the other two kayas are form-bodies arisen from the first.

- ↑ Reference: D.T.Suzuki, 1959, Zen and Japanese Culture, Princeton University Press, pg. 272-273.

- ↑ Reference: D.T.Suzuki, 1959, Zen and Japanese Culture, Princeton University Press, pg. 276-289.

- ↑ Suzuki explained “tranquility”(jaku) to have same meaning as sabi or wabi which is an active appreciation of the lack of things. This is an important understanding and application on Japanese culture and aesthetics.

- ↑ Reference: Burton Watson, 1997, The Vimalakirti Sutra, Columbia University Press, pg. 25.

Source

Buddhism And Australia Conference 2015 http://buddhismandaustralia.com/