Buddha and the Snake-king

Whenever a new religion appears it must find a way to cope with the old religions that surround it.

Buddhism is no exception.

We all know that the religion practiced in India during Buddha’s life time was as it is today Hinduism. Today Hinduism is said to be the third largest religion in the world.

But Hinduism does not have a "unified" system of belief encoded in declaration of faith or a creed but is rather an umbrella term comprising the plurality of religious phenomena originating and based on the Vedic traditions.

Various schools of Hinduism may adopt beliefs spanning monotheism, polytheism, pantheism, monism, and atheism.

One of the oldest “denominations” of Hinduism is what we would call snake or serpent worship.

It is known in fact to predate the Aryan culture on the Indian continent.

I think it would surprise many folks to know that the worship of snakes and/or Naga arose in India over 500 years before Buddha’s birth and is still alive and well all over India today.

This cult of the serpent has been shown to have existed over the entire continent and in fact from around 1250 BC until around 550 AD Snakes were worshiped in Persia and what is now called Arabia and Egypt.

It would appear that snake worship originated in India and spread across both the near, middle and Far East.

As in all religions there were different types of serpent worship in India.

In Northern India, a version of the serpent worship evolved around the Naga called Vasuki and known as the “king of the serpents” was worshipped.

These were the Naga of both Buddhist and Hindu religion.

Innumerable shrines containing images of the snake king Vasuki bear testimony to the influence of serpent on the social and spiritual fabric of India.

In southern India the serpent cults had a tendency to simply worship actual live snakes.

In Sanskrit the world naga simply means serpent or snake.

But in both Hindu and Buddhist writings and art the nagas are serpent creatures that are depicted as having human upper torsos but are snakes from the waist down.

In Buddhist iconography, nagas sometimes are giant cobras, and sometimes they are more like dragons, but without legs.

They are shape sifters who can take on the form of large snakes or even humans.

It would appear that just as there was one kind of serpent worship in northern India and another in southern India.

Buddhism itself divided in what was for years called Northern Buddhism and Southern Buddhism;

Mahayana in the north and Theravada in south.

The way each of these schools chose to deal with the snake cults is significant and may in fact reflect one of the causes of schism between the two schools of Buddhism.

It is clear that the Mahayana schools chose to adopt and assimilate the northern Hindu system of serpent worship into their own beliefs and myths.

In Mahayana Buddhist sutras and myths, nagas usually are wise and beneficent.

While one Theravadin story recounts that Sanghamitra, daughter of king Ashoka, had once to assume the form of Garuda (a bird deity and enemy to the Naga) to counteract the magic power of the Nagas who tried to snatch the branch of the Bodhi tree she was carrying with her on her way to bring Buddhism to Ceylon, now Sri Lanka.

Most Theravadin stories about snakes are ways of warding off snake bites and other more particle issues.

In Mahayana Buddhism, nagas often are depicted as water deities who guard the sutras in their palaces.

For example, it is said the Wisdom Sutras were given to the nagas by the Buddha, who said the world wasn't ready for their teachings.

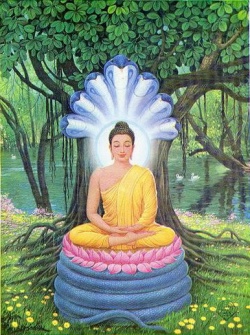

In Mahayana Mythology it is the Naga-King Vasuki known as the “king of the serpents”

That comes to Buddha in the form of a giant Cobra under the Bodhi tree and spreads his hood like an umbrella over the Buddha for seven days and nights to protect him from the monsoon rains.

The Lotus sutra is said to be the primary Mahayana sutra and key to its development across Asia.

In the Lotus sutra eight great Nagas come to hear the Buddha teach and are converted on the spot.

From that day on words the Nagas were said to be the protectors of the Dharma.

Perhaps the first Buddhist female hero was the daughter of the Naga-King whose story is recounted in the Lotus Sutra.

She is said to have come to the Buddha and to have given him the famous “Wish Fulfilling Jewel” said to be more valuable than the entire earth.

That Mahayana Buddhism was still dealing with the serpent cult’s years after Buddha’s death is clear in the story of Nagarjuna.

This sage who is sometimes called the second Buddha is said to have been given his name because of his relationship with the Naga.

The story goes that “Two youths, who were emanations of the sons of the naga king, came to Nalanda.

They had about them the natural fragrance of sandalwood.

Nagarjuna asked how this was so and they confessed to him who they were.

Nagarjuna then asked for sandalwood scent for a statue of Tara and the nagas’ help in constructing temples.

They returned to the naga realm and asked their father, who said he could help only if Nagarjuna came to their realm beneath the sea to teach them. Nagarjuna went, made many offerings, and taught the nagas.”

The legend goes that when Buddha taught the great perfection of wisdom teachings his cousin Ananda gave a copy to the Naga king for safe keeping.

The Buddha said that the people of his day were not ready for those teachings.

It was Nagarjuna that requested a copy from the Naga and brought back with him The Hundred thousand verse sutra on the Prajna Paramita.

It is said that once while he was teaching the prajna Paramita six Naga came and sheltered him from the rain much as the Naga-King had done Buddha.

From these stories it is said, he got the name Naga.

And from the fact that his skill in teaching Dharma went straight to the point, like the arrows of the famous archer Arjuna (the name of the hero in the Hindu classic, Bhagavad Gita), he got the name Arjuna.

Thus, he became called “Nagarjuna.”

Historically speaking at some point the myths of the Naga and the serpents clearly allowed Buddhist to assimilate local snake cults into Buddhism and allowed the two belief systems to coexist.

In most of the Mahayana stories the Nagas are either converted to Buddhism or seen as protectors of Buddha and the Dharma.

When Buddhism made the trip through China the Naga became dragons as well as snakes and once again were incorporated in the Buddhist belief system.

The Shinto shrines to the Dragon spirits or Kami were easily incorporated into a long established mythology of the Naga.

This certainly eased the relationship between the Shinto priests and the Buddhist priests.

I will end this essay with a nice little tale from Tibet about the Naga.

“According to the Vinaya or Buddhist Monastic Rule, an animal cannot become a monk.

At one time, a Naga was so desirous of entering the Order that he assumed human form in order to be ordained.

"Shortly after, when asleep in his hut, the naga returned to the shape of a huge snake.

The monk who shared the hut was somewhat alarmed when he woke up to see a great snake sleeping next to him!

The Lord Buddha summoned the naga and told him he may not remain as a monk, at which the utterly disconsolate snake began to weep.

The snake was given the Five Precepts as the means to attaining a human existence in his next life when he can then be a monk.

Then out of compassion for the sad snake, the Lord Buddha said that from then on all candidates for the monkhood be called 'Naga' as a consolation.

They are still called 'Naga' to this day."