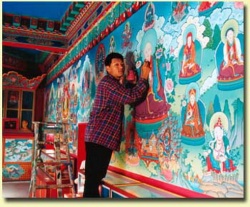

Buddhism During the Song Period

There were many reasons for the decline of Buddhism (Fojiao 佛教) after the Tang period 唐. The most apparent factor destroying the eminent position of Buddhism in Chinese society, economy and politics were the several persecutions of Buddhism and other religions during the 8th and 9th centuries. It was in first place economical reasons for these persecutions - monasteries were tax-free units, and monks were not obliged to pay taxes or labour corvée. The more people were "hiding" inside the ranks of the clergy, the less people were tax-liable and could be mobilized for official works or military service. The Song Dynasty government developed a regular tool to increase state revenues by selling certificates (dudie 度牒 - a practice already begun during Tang) to ordained monks by which they could prove that they were exempted from tax and labour services. But as soon as buying such a certificate was enough for being tax-exempted there was no further duty for a Monk to exert the life of a Monk as he was expected to do. People wealthy enough to buy a Monk certificate could enter any monastery. This practice lowered the quality of the monasterial community (Sanskr. Sangha, Chin. seng 僧) and discredited moral integrity and the reputation of Buddhist sanghas, even the highest dignitaries by selling their titles (shihao 師號) and their privilege to wear the purple robe of a patriarch (ziyi 紫衣). During the Southern Song, the sales of Monk certificates were abolished, and a poll tax imposed upon clergymen was introduced.

The rise of Neo-Confucianism (often equalized with the School of Principles, lixue 理學 which is actually only one branch of Neoconfucian theoreticians) with its interest in metaphysical discussions became a far more attractive ideology for the scholar-officials of the Song period than the purely religious Buddhism. Neo-Confucian theoreticians incorporated Buddhist problems into the framework of traditional Chinese, especially Confucian, thinking, and made it obsolete for the scholars to be a true Buddhist believe - the study of Buddhism and the adaption of some of its ideas was sufficient, and Neo-Confucians produced their counter-theories against Buddhist doctrines, like the emptiness (Sanskr. śūnyatā, Chin. kong 空) of the phenomenal world as opposed to the Neo-Confucian ether-essence qi 氣 that is incorporated in every substantial and non-substantial phenomenon through an immmanent principle of "order" li 理. The emergence of Neo-Confucian ideas experienced an intensive support by government with the introduction of the state examinations that required the studies of the Confucian Classics (Five Classics and Four Books Wujing Sishu 五經四書) and totally neglected Buddhis sutras.

While some Tang period monks undertook long journeys to go to India and to bring back sutras and other Buddhist writings in the Sanskrit original to translate them into Chinese when back, the occupation of the gateway to the west by the Uighurs and the Tangut empire of Western Xia (Xixia 西夏) as well as the decline of Buddhism in its home country in India also contributed to the stagnation of Buddhism in China. Here, the old traditional schools or sects (Tiantai 天台宗, Huayan 花嚴宗, Consciousness-Only-School (Weishizong 唯認宗], Vinaya School (Lüzong 律宗)) were gradually replaced by new sects that became much more popular and are often equalized with Buddhism itself: The Chan Sect (Chanzong 禪宗; in the West better known with its Japanese name Zen, Zenshū 禅宗) and the Pure land Sect (Jingtuzong 淨土宗). Both sects disregarded the study of sutras and the observation of monastic rules (Sanskr. Vinaya, Chin. lü 律) and emphasized instead intuition, simple faith and the mechanical recitation of formulas. Such simple types of beliefs were very attractive for the broad masses but they did not lead to a productive development of religious scholarship. Nonetheless these two sects were a very handsome tools for the Song period emperors who wanted to control the Buddhist communities and who founded many Chan monasteries throughout the country and bestowed the highest titles of Buddhist clergy through imperial order (hence called Monk-officials sengguan 僧官). It was easier to cope with one single sect and its representants than with many different concurring streamings. Taxation of monasteries became more and more the regular case during the Song period. Persecutions of Buddhism did never occur after the Tang period, and the only attempt to attack Buddhism by Emperor Huizong 宋徽宗 was rather an experiment to dao-ise Buddhism by changing terms and titles.

State sponsoring of Buddhism began early in Song, when Emperor Taizu 宋太祖 dispatched an envoy of monks to India (Tianzhu 天竺), had printed the Buddhist canon in Chengdu 成都/Sichuan, contemporary center of printing technology and had insiced Buddhist writings - including imperial prefaces - into stone slabs. Emperor Taizong 宋太宗 had erected several large pagodas in the largest cities of the empire. The most important editions of the Buddhist Tripitaka during Song were the Kaibao Tripitaka 開寶藏 from 983, Chongning Tripitaka 崇寧藏 from 1103 and the Pilu Tripitaka 毗盧藏 from 1151, the first printed in Chengdu, the others in Fuzhou 福州/Fujian.

The Chan Sect

Chan Sect monasteries and temples were points of attraction, they were centers of social life within the large cities of the Song empire. Bustling with life and acting as economic units (storehouses, shops, mills, guesthouses etc.), they totally contradicted the original intention of Chan Buddhism that was introvertive and retrogressive, avoiding the large cities. Although Chan monks disregarded the study of sutras they collected many intellectual discussions made among the monks by which they attemped to gain sudden elightening (Chin. wu 悟, Jap. Satori; Sanskr. Bodhi). The senior Monk asked the adept a problem (called "legal case" gong'an 公案, Jap. Kōan) he had to resolve or at least to answer in his own way, often in an unexpected or unconventional way. The most important types of these "Enlightenment riddle" collections are yulu 語錄 "recorded sayings" and denglu 燈錄 "lamp records", two very important writings are Biyanlu 碧巖錄 "Records of the Jadegreen Cliff" and Wumenguan 無門關 "Gateless Passage". The name of the Chan Sect is derived from the Sanskrit word for meditation (Dhyāna) which is corrupted to chan in Chinese pronunciation. Meditation was thus another important tool for attaining Enlightenment or event the buddhaship.

The Song period Chan sect can be divided into seven different schools and five houses (wujia qizong 五家七宗) that each emphasize different methods to attain buddhaship. To the most important schools belongs the Gui-Yang School 溈仰宗, founded by two different monks during late Tang. Gui-Yang teaching stresses the mystery of the Dharma (fa 法 "teachings" of The Buddha) that can not be expressed by words, particularly because every being stores in it the nature of The Buddha. The Fayan School 法眼宗 was represented by the Monk Yanshou 延壽 who wrote the treatise Zongjinglu 宗鏡錄 "The Mirror of Schools/the Patriarch" that tried to exchange thoughts and theories with the Tiantai School in a movement for the reapproach of Chan and traditional schools (Chan jiao he yi 禪教合一). A similar attitude can be observed with Qisong 契嵩 (wrote Fujiaopian 輔教篇 "Assisting the teaching/religion") from the Yunmen School 雲門宗, one of the most important persons working for the harmonization of China's philosophies and religions. The most important Chan school even outside China was the Linji School 臨濟宗 that institutionalized the intuitive teaching of the Chan sect, a process that can be observed in the vast treasure of Chan writings that were published by Linji monks who collected the enlightenment riddles (gong'an, jifeng 機鋒), created exemplarious answers (daiyu 代語) or alternative answers (bieyu 別語), interpreted examples of the first decades of Chan activities (songgu 頌古, niangu 拈古). Analyzing (jijie 擊節) and rearranging the Chan teachings in a critical literary style (pingchang 評唱), they published annotated collections of Chan teachings, like Biyanlu, Jijielu 擊節錄 "Record of Ingressive Analysis", or Wudeng huiyuan 五燈會元 "Assembling the Origins from the Five Lamps". Less important for the history of religions was the Cao-Dong School 曹洞宗 and the two minor groups of the Huanglong School 黃龍派 and the Yangqi School 楊岐派.

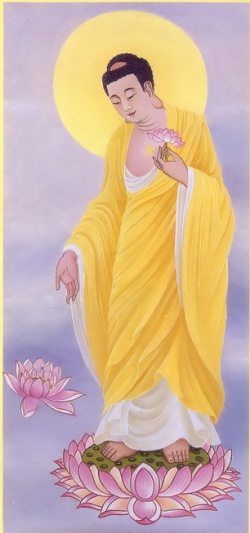

The Pure land Sect and the Amitabha Buddha

The Pure land Sect belongs to the oldest Mahayana Schools in China. The most important deity of this sect is the transcendent Amitābha Buddha (Chin. Amituofo 阿彌陀佛, Jap. Amida Butsu 阿弥陀佛; also called Amitāyus), The Buddha reigning the Pure land "paradise" in the west (Sanskr. Sukhāvatī). The believer is simply required to recitate mechanically the name of the Amitābha (an activity called nian fo 念佛 "reciting The Buddha"), like a mantra verse. Repeating often enough, salvation for oneself of a deceased person can be expected. Jingtu Sect and Chan Sect patriarchs (fashi 法師) tried to approach each other and to establish a more harmonious relationship to each other than schools of previous school had exerted. The Pure land Sect is today the most important Buddhist school, a position that it had acheived through the simplification of Buddhist practice from that of a clerical religion to a popular religion. Redemption was seen now in the entry into The Western Paradise after death, rather than attempting into Nirvana after a sophisticated and pretentious process of Enlightenment. The most important Song period representants of this "mind-only" religion (weixin 唯心, the Buddha-nature is implicitly buried in everyone, and salvation will thus be come upon everyone - a deceased person becomes automatically a Buddha, or Hotoke in Japanese) were the monks Shengchang 省常 and Zongze 宗賾.

The Bodhisattva Guanyin

A second deity being highly venerated since the Song period was the Bodhisattva Avalokiteśvara, companion of the Amitābha and a deity that - although having attained buddhaship - refrains from entering the nirvāna for his compassion (Sanskr. karuņā) for other beings that he wants to support during their search for salvation. Originally a male, the Avalokiteśvara transforms into a female being from the 10th century on and was in his Chinese shape called Guanyin 觀音 (Jap. Kannon 観音; short for Guanshiyin 觀世音 or Guanzizai 觀自在) "Observing the Sounds of the World". Basic Sutra for the belief in the Avalokiteśvara is the Lotus Sutra (Miaofa lianhua jing 妙法蓮花經; Sankr. Saddharmapundarīka-Sūtra). The most popular form of Guanyin is the White-Robed Guanyin (Baiyi Guanyin 白衣觀音), mother deity and patron saint for everyone in danger and distress, thus a kind of Buddhist Mother Mary.

The Tiantai Sect

The Tiantai Sect 天台宗 experienced new impulses by the monks Zhili 知禮, Zunshi 遵式 and Wu'en 悟恩. In his book Fahuaqian 法華懺 "Confessions of the Flower of the Dharma" Zhili explains the one-ness of mind (xin 心), shape (se 色) and The Buddha (Fo 佛), 一念三千, 圓融三諦,一乘圓教. Zunshi, talking about the nature of the dharmas (fa 法), the appearances of all Sentient beings, declared that nature (xing 性) and the mind are one and the same.

The Laughing Buddha

A very Chinese transforming of the Maitreya Buddha (Milefo 彌勒佛), Buddha of the future, was the Laughing Buddha (Hafo 哈佛), also called "Bigbelly Buddha" or "Potbelly Buddha". The Maitreya was a common deity of the early Tang sculptures but was replaced from the 7th century on by the Amitābha Buddha and the Bodhisattva Avalokiteśvara. Only in the 10th century the Maitreya again became the focus of Buddhist veneration. The Milefo with his hempen bag is a mere representation of Chinese life ideals: the big belly symbolizes wealth and prosperity, his reclining pose shows spiritual contentment and relaxation, and the many children surrounding him reflect the wish for a great family. He can thus be almost identified as member of a group of popular deities that are invocated when looking for health, long life, prosperity and many descendants.

Popular Buddhist Sects

The White Cloud Sect (Baiyunzong 白雲宗) was a popular type of Buddhism that became prevalent during Song and still survives today. Reciting the name of The Buddha, renouncing meat (chisu 吃素) and studying are three factors that can bring salvation. The founder, Qingjue 清覺, has written the encyclopedia Chuxueji 初學記 "First Step of Learning" and the collection Zhengxingji 正行集 "On the Right Conduct", two kinds of literature that rather fit into the pattern of scholarly Confucian writings and thereby show the integration of the two doctrines of Buddhism and Confucianism.

- A second popular sect was the White Lotus Sect (Bailianzong 白蓮宗 or Bailianjiao 白蓮教), founded by Mao Ziyuan 茅子元, that was very popular in the region of Jiangsu and Zhejiang. The simply form of religious performance without monastic life and intensive rituals or practices was so attractive that the White Lotus Sect received so many members that it became an important political factor during peasant unrests of the Southern Song and especially at the end of the Yuan Dynasty 元.