Buddhism in China by Jeffrey Hays

China was the only Buddhist country that possessed a civilization before the introduction of Buddhism. For over a thousand years Buddhism dominated religious life in China, having both a profound impact on China and Buddhism and producing a great body of literature and art. China was the conduit through which Buddhism reached Korea, Japan and Vietnam. The Buddhism found in China is almost exclusively Mahayana.

Buddhism in China has gone through cycles of rising, flourishing and declining. Over the centuries it has been shaped by the tensions between the Indian-influenced traditions and Chinese traditions. In the eyes of many scholars the tension is what kept Buddhism alive and relevant. When the tensions waned so too did the religion. At its peak Buddhism had hundreds of millions of followers and deeply shaped Chinese culture and thought.

Buddhism entered China mostly in the Mahayana form as it was going through many changes in India. Each major change resulted in a new school in China. Chinese Buddhism evolved through the study of sutras in Chinese. Doctrinal issues were addressed using different sutras than those used in India. The various schools tended to differ from each other and from those in India based on the sutras they emphasized as being truest.

Buddhism is regarded as the largest religion in China today, with 100 million followers, or about 8 percent of the Chinese population, including Tibetans, Mongolians and a few other ethnic minorities like the Dai. There is roughly around the same number of Christians and Muslims. According to the State Administration for Religious Affairs there are about 13,000 Buddhist temples and about 200,000 Buddhist monks and nuns. Still, it can be argued that Buddhism is not embraced with the same enthusiasm and devotion as it is in other Asian countries and in Tibet. Many Buddhist temples in China are watched over by caretakers not monks. In Japan and Korea, many people are buried according to Buddhist rites, but that is not usually the case in China.

When Buddhism reemerged after the Cultural revolution it was simpler and more influenced by the West. While Tibetan Buddhism encourages lamas to counsel students individually, Chinese Buddhism puts more emphasis on teaching monks in groups in monasteries.

Buddhist Printing in China

Buddhist monasteries were instrumental in the development of the world’s first block printing in China in the A.D. 7th century. Buddhists believe that a person can earn merit by duplicating images of Buddha and sacred Buddhist texts. The more images and texts one makes the more merit one earns. Small wooden stamps—the most primitive form of printing—as well as rubbings from stones, seals, and stencils were used to make images over and over. In this way printing developed because it was "the easiest, most efficient and most cost effective way" to earn merit.

The world's oldest surviving book, the Diamond Sutra, was printed in China in A.D. 868. It consists of Buddhist scriptures printed on 2½-foot-long, one-foot-wide sheets of paper pasted together on one 16-foot-long scroll. Because virtually all original Indian scriptures have been lost Chinese translations of Indian scriptures have been invaluable in trying to figure out what the original Indian texts said.

Buddhist Art in China

As Buddhism, took root in China, it became a major cultural force, inspiring some of China’s most brilliant paintings and sculptures.

Buddhists filled caves throughout China with sculptures and murals. In the cliffs of the Tian Shan mountains in the Kumtura and Kizil regions of Xinjiang province in western China, for example, there are hundreds of caves adorned with Buddhist painting that date as far back as the A.D. 5th century. Scholars believe the paintings—many depicting episodes from the lives of the Buddha Siddhartha Gautama, painted using paint made from ground minerals such as malachite for green and iron oxide for red—were commissioned by lay people and painted by local artists

Early Buddhist art from the A.D. 5th century was influenced by the Hellenized Central Asian cultures of Kushen and Ganden and embellished with Chinese ornamentation. This art was mostly in form of Buddha statues and stelae, some of them dated and inscribed with their donor’s name, carved out of rocks in caves such as those in Yungang near the Great Wall.

The periods of Chinese Buddhist art closely parallel the phases the Buddhist religion was going through in China . Works that appeared in the 5th and 6th centuries were very free and individualistic. In the Tang period the art became more mature and robust, with Buddhist figures featuring graceful lines and curves. In the 10th to 13th century it became more refined. After that it was rooted in tradition and lacked innovation.

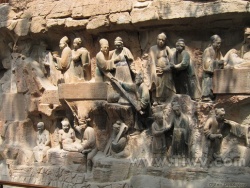

Buddhist Sculpture in China

The most well known sculptures to come out of China are the images of Buddhas found in caves and sculptures unearthed from tombs.

Some of the most exquisite Chinese sculpture was discovered at Qingzhou in Shandong in 1996 by workers leveling a sports field at a school. First the stone head of a Buddha was uncovered. Underneath that was pit were 188 heads and 200 virtually intact torsos, and some monumental steles with Buddhist triads, and clay figures that were once brightly painted, some of them with “ash and burnt bones.” The pieces were quickly excavated and stored in a museum without serious archeological work being done. They were of varying styles and time periods, and seemed like someone's private collection.

Wonderful 6th and 7th century Buddhist sculptures have been unearthed in northern China along the [[Silk Road]] in Gansu and Ningxia. These include a big-nosed clay representation of a Buddha disciple, a granite carving of Avalokitesvara, a popular Buddhist deity; and a bronze figure of a dancing Sogidian. Many of the work bear influences from Persia and Central Asia. The Sogdians were a Persian culture centered around Samarkand

A relief a Buddha flanked by two bodhisattvas and a life-size bodhisattva feature extraordinary detail and expression. Souren Melikian wrote in the International Herald Tribune, “A seated Buddha that was once enthroned represents a classical moment of its art. The perfect proportions project a sense of harmony and the expression of imperious illumination speaks of a powerful, self confident art. A figure in motion is unique in the art of China, with its knees very slightly flexed lifting the light drape adhering to the body.”

Chinese Buddhists Texts and Deities

The Chinese Tripitaka contains both Indian writing and Chinese contributions. Each school selects two or three sutras as its basic authority. Versions vary often based on the decisions of editors rather than religious councils. The entire Tripitaka is a massive. An effort to print the entire thing in 980 required 130,000 printing blocks. A modern version published in Japan in the 1920s is comprised of 55 volumes. They largest sections are Mahayana sutras and Chinese commentaries on them.

Important Buddha images in Chinese Buddhism include the

- 1) Sakyamuni Buddha (historical Buddha), associated with the Tien-tai and Ch’an sects and the Saddharmapundarika sutra, the most popular sutra in China;

- 2) Amitabha Buddha (Amit’o, Buddha of the Western Paradise), associated with the Pure Land sect;

- 3) Maitreya (Milo), the Future Buddha;

- 4) Bhaisajyaguro Buddha (Yao-shih), “The Master of Healing,” who presides over the Eastern Paradise and us often sought by worshipers with troubles.

Important Bodhisattvas in Chinese Buddhism include:

- 1) Avalokitesvara Bodhisattva (Guanyin, Kuan-yin), who possesses the power to help all those suffering from a number of troubles including fire, poison and wild beasts

- 2) Kshitigarbha Bodhisattva (Ti-sang), who specializes in rescuing beings from hell. Chinese Buddhist seek help from these Bodhisattvas as well as the Buddhas Tao-shih and Amit’o in personal matters.

Chinese Buddhist Schools and Sects

As Buddhism developed it splintered into many schools and sects, each with its own distinctive traditions, doctrines and practices. Sub-sects—representing lineages of disciples that split off from the main schools often over minor doctrinal differences—and cults—that conducted special observances and rituals often focused on a particular sutra and kept alive by a lineage of masters—also developed. Despite the large number of groups and subgroups monks tended to be initiated into the general Buddhist community rather than into a particular school, sect or cult.

School and sects in China generally fall into one of three categories:

- 1) classical schools, which are based on a particularly sutra and trace their origin back to India;

- 2) catholic sects, based on different sutras, often ones oriented toward reaching enlightenment selected by the founder of the sect

- 3) exclusive sects, which advocate a single path and select the systems and sutra to suit that purpose.

The two exclusive sects are:

The four principal classical schools are : 1) the Kola School, based on doctrines from India translated by Hsuan Tsang;

- 2) the Satyasiddho School, based on Kumarajiva’s translation of the Satyasiddhi sutra;

- 3) the San-Lun (Three Treatises) School;

- 4) the Fa-hsiang School, founded by Hsuan Tsang.

The three primary Chinese Buddhist sects are:

- 1) Tien-tai (T'ien-t'a), founded by Chih-I (A.D. 538-97) and oriented around the Lotus sutra and a system of meditative exercises;

- 2) Hua-yen, founded by Tu-Shan (A.D. 557-640), refined by Fa-tsang (643-712) and based on the Avatamsaka (Hua-yen) sutra

- 3) Chen-yen (True Word), introduced by Indian missionaries about A.D. 720.

The Tien-tai school has its own liturgy. Followers believe that the secret of enlightenment lay in a balance of meditation, moral discipline, rituals and study of scriptures. The Hua-yen sect emphasizes a step-by-step approach to enlightenment, featuring meditation exercises aimed at discovering the Realm of Essence.

Members of the Chen-yen Schools use secret ceremonies, mime and spells to achieve salvation. It features a ten-stage system of religious life, a baptism-like consecration and meditation exercises based on contemplating symbolic representations of the five chief Buddhas using certain spells and chants and ritual gestures repeated again and again.

Ch'an Sect of Buddhism

The Ch'an (or Ching’T’u) Sect has been described as a religion of “wisdom or intuitive insight” and is the inspiration for the Zen school of Buddhism in Japan. Ch'an means mediation. Its key elements are summed up by the four phrases:

- 1) “A special transmission outside of doctrines”;

- 2) “Not setting up the written word as an authority”;

- 3) “Pointing directly at the heart of man”;

- 4) “Seeing one’s nature and becoming a Buddha.”

The Ch'an sect’s origins are obscure. It is it not clear whether its early patriarchs were legendary or real. Under the leadership of its sixth patriarch Hui-neng (A.D. 637-723) it grew from a cult with around 500 members to a distinct sect after Hui-neng spent 15 years meditating in the hills.

Zen Buddhism evolved out of the Ch'an School, which was introduced to Japan from China during the Chinese Sung Dynasty in the 10th century by a Chinese monk named Huineng. Zen initially had a relatively small following and didn't take hold and flourish in Japan until the 12th century.

Ch’an aesthetics had a great impact on Chinese and Japanese art. Ch’an artists rejected the symmetry and iconography of the Sino-Indian tradition. They aimed for extreme economy and means by trying to get the most meaning possible out of each line and shade to suggest a maximum of intensity, rhythm, special counterpoint and tonal harmony. For artists painting became a contemplative exercise; for viewers it became a form of meditation.

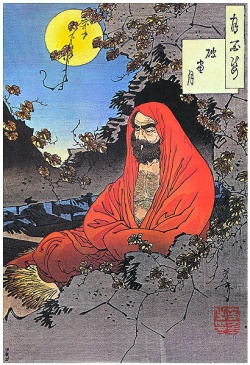

Bodhidharma

The Ch’an school is said to have been founded by Bodhidharma, a south-Indian prince who became a monk and traveled to China around A.D. 520. It is not clear whether he was a real person or not.

According to legend, when Bodhidharma arrived in the Chinese capital of Nanking, the devout Chinese Emperor asked him how much merit he had earned building temples and copying scripture. Bodhidharma replied: “No merit at all...All these are inferior deeds, which would cause the doer to be born in heaven or earth again. They will show the traces of worldliness. They are like shadows following objects. A deed of true merit is full of pure wisdom and is beyond the grasp of conceptual thought. This sort of merit is not found in any worldly works.” The Emperor then asked what is the holy truth? Bodhidharma replied: “Great Emptiness, and there is nothing in it to be called holy.’ The emperor then asked him who was. Bodhidharma said; “I do not know.”

After this sharp condemnation of the pursuit of merit as basically selfish and self-indulgent, Bodhidharma left for northern China and meditated for nine years by staring at the wall of a cave. He sat there so long in meditation it is said that his legs fell off. To battle his occasional bouts of drowsiness he cut off his eyelids so his eyes wouldn't close.

While Bodhidharma was meditating a monk named Hui Ko came to visit him and seek the answer to troubling questions and calm his mind. Initially Bodhidharma was so absorbed in mediation that he did not notice the monk. Hui Ko waited in snowdrifts for some time but received no response. Finally he cut off his arm and gave it to Bodhidharma who at that point gave his attention to the monk. Hui Ko received the advise he sought and later became the second patriarch.

Bodhidharma is associated with ascetic discipline, serious mediation, yoga, psychic power and the Shaolin school of martial arts. He said: “A special tradition exists outside the scriptures, not dependent on words or letters; pointing directly into the mind, seeing into one’s own nature and the attainment of Buddhahood.”

Ch'an Sect Beliefs

Ch'an Buddhism teaches that salvation comes from inner enlightenment, something that happens in a brief instant, often through meditation. It also emphasizes concrete thought over metaphysical speculation, often with lofty, paradoxical statements, and views teaching as something beyond the written and spoken word that is best transmitted directly from master to disciple. The use of images and sacred texts is frowned upon by the Ch'an School.

Ch’an gets most of its ideas directly from Mahayana sutras but is regarded as unique with it sharp, unwavering positions and emphasis on realization through insight. It has its own monastic system, which requires monks to do manual labor, and emphasizes the use of special training exercises in which disciples are peppered with questions and given metaphysical riddles or questions—such as whether dogs can become Buddhas or bricks can be polished into mirrors—by the their masters who attempt to develop the disciple's reasoning, insight and wisdom.

Summing up the philosophy of the sect the third Ch’an patriarch Seng-tsan said: “The more words, the more reflection, the less you understand the way; Cut off words, cut off reflection, and you penetrate everywhere. Events in the void before you all spring from mistaken notions; It’s useless to seek for the true—you must just quiet your notions.”

School of Pure Land

The School of Pure Land (known is Japan as the School of Pure Thought) is another important Chinese school of Buddhism. It emerged about A.D. 500 as a form of devotion to Amitabha, the Buddha of the Western Paradise, and differs from the Ch'an school in that it encourages idolatry. The School of Pure Land is not nearly as strong in China as it once was but it remains one of the largest Buddhist sects in Japan.

The School of Pure Land takes the Mahayana belief in Buddhas or Bodhisattvas a step further than Buddhist traditionalists want to go by giving Bodhisattvas the power to help people attain enlightenment that they otherwise would be unable to attain it on their own. The emphasis on Bodhisattvas is manifested in the numerous depictions of Buddhas and Bodhisattvas in Pure Land temples and caves.

Some historians believe the School of Pure Land originated in India but there is no definitive proof of this because the oldest known texts are in Chinese not Sanskrit. Others say the sect was founded by the Chinese monk Hui Yuan (A.D. 334-417). In any case as the school became popular in China, images of Buddha and Bodhisattvas acquired Chinese names and statues of the sitting Buddha (in meditation) and the sleeping Buddha (asceticism) were raised all over the country.

School of Pure Land Beliefs

The purity referred to in the School of Pure Land is the state a Bodhisattva attains upon achieving enlightenment. Followers of the school believe that impure people can attain their own personal enlightenment by linking themselves with a Bodhisattva, notably Amitabha/Amida, the Buddha who set up and rules over the Western Paradise. Pure Land followers believe that no matter how wicked a person is they can attain a form of enlightenment with simple faith, that is some cases is manifested simply by murmuring a few phrases.

The idea is that rather than striving for enlightenment by the accumulation of merit through good deeds and morality an individual can be transported with the help of a Bodhisattvas to a “Pure Land”—the Western Paradise of Amitabha—in his or her next life where attaining enlightenment is profoundly easier than on earth. Amitabha is said to have the power to grant salvation to all those who have faith in him. The moment a believer places his faith in Amitabha he or she is said to have attained a measure of enlightenment.

In the school of Pure Land there is a strong emphasis on devotion. Monks are required to go through a head-shaving ceremony. Followers are expected to abandon all desire, even the desire for enlightenment, and entrust themselves totally to the power of Amitabha. Other practices associated with the school are the chanting of the nembutsu, a simple mantra that goes “Namu Amida Butsu” (“Adoration of the Buddha Amitabha”)

The religious scholar Richard Robinson wrote that Pure Land and Cha’an. sects “differ markedly in several ways: one is pietist, the other is mystic; one stresses faith, the other insight; one requires absolute reliance on the word of a Scripture, the other relies not on Scriptures but on a special transmission from mind to mind...The Pure Land devotee commonly belongs to the Buddhist typology, to the ‘tribe of lust,’ while the Ch’an devotee belongs to the ‘the tribe of wrath’...But both reject the gradual course and...are essentially ‘sudden’ teachings...Both claim a way to infinite merit.”

Chinese Buddhist Temples

Buddhist temples are generally a cluster of buildings—whose number and size depends on the size of the temple—situated in an enclosed area. Large temples have several halls, where people can pray, and living quarters for monks. Smaller ones have a single hall, a house for a resident monk and a bell. Some have cemeteries.

Temples can be several stories high and often have steeply sloped roofs that are supported on elaborately-decorated and colorfully-painted eaves and brackets. The main shrines often contain a Buddha statue, boxes of sacred scriptures, alters with lit candles, burning incense and other offerings as well as images of Buddhas, Bodhisattvas and devas. The central images depends on the sect.

Buddhist temples usually have red pillars while Taoist temples have black ones. Just inside a Buddhist temple gates are statues or images of the Four Heavenly Kings of the Four Directions and Maitreya, the chubby laughing Buddha. The main hall features three large statues seated on lotus flowers: the Buddhas of the past, present and future. Behind them is often a statue of Guanyin, the multi-armed Goddess of Mercy.

Some Chinese Buddhist temples invite Tibetan monks in an effort to attract to more followers.

Many temples are funded by donations with large amounts of money for prestigious temples coning from Buddhists in Hong Kong and Taiwan and elsewhere around the world.

Chinese Buddhist Monks

Chinese Buddhist monks usually have shaved heads and wear grey robes.

Monks in Shanghai are learning foreign languages, improving their computer skills and taking classes in financial management as part of their effort to keep Buddhism modern and relevant.

A monk at Shanghai’s Jade Buddha Temple told the Los Angeles Times, “Some people think monks should do nothing but sit around and read scriptures. The times have changed—we have to change too, If we stay the same, we can’t survive.”

Another monk at the Jade Buddha Temple told Reuters, “The first thing I do in my daily work is open the laptop and check e-mails and surf the Internet. Everything in the temple is now processed online. No paperwork. Those who failed the computer test were laid off and reassigned nonoffice jobs."

Describing the routine at Jade Buddha Temple he said, “We are very busy, no weekends or vacation. Interacting with the outside world occupies most our time, so many monks have to use the noon break if they want to do meditation...Before everyone including the abbot had to clean the temple, and old monks were assigned to check tickets and guard the temple. But they often smoked and fell asleep, causing bad influences, Now we have hired professional service companies to be responsible for temple security and cleaning. This works very well.”

Chinese Buddhism Today

Beijing generally feels less threatened by Buddhism than it does Christianity because of its homegrown roots, but t does maintain control over monasteries, especially in Tibet. Buddhism strong association with Tibet doesn’t make it making it very popular with the Communist regime.

In August 2004, a U.S.-based Buddhist leader was detained and dozens of his American followers were forced to leave the country. The leader and his group has spent $3 million renovated a 800-year-old temple in Inner Mongolia. The leader, who is regarded as a “living Buddha,” was charged with “promoting superstition” and taking control of the temple.

In March 2006, China hosted its first major international forum on Buddhism since 1949. About 1,000 monks and scholars from 10 countries, including Hong Kong and Taiwan attended. The theme of the forum was “a harmonious world begins in the mind.” The 16-year-old Panchen Lama showed up at the event and gave a scripted, pro-Beijing speech. Human rights groups called the meeting “cynical propaganda aimed at drawing attention away from China’s repressive policies in Tibet."

Business-Minded Chinese Buddhist Monks

Several monks at Jade Buddha Temple have gotten MBAs, with special classes in temple management, at the Antai School of Management. The temple’s manager Chang Chun told the Times of London, ‘We live in the metropolis of Shanghai and need to find a way to interact between Buddhism and society. This requires a different management style.’ A monk taking the course said, ‘We have a strong sense of faith but our commercial knowledge is weak. Now we have many more opportunities to meet people from the secular world and need to understand how o deal with and negotiate with outsiders.’

Behind Jade Buddha Temple is a glass-and-marble building where its business-minded monks work and figure out ways to make money and better manage their temple. Jane MacCartney of the Times of London wrote, ‘In temple offices, shaven-headed monks dressed in saffron robes sit in cubicles like those fond in London banks. Some peer at computer screens and answer telephone calls; others monitor visitors by walkie-talkie.]

Entrance to the temple is $1.35. Bunches of incense sticks are sold for about $5 at the temple shops. Around the temple are boxes for donations. For $1,360 one can buy a gilt Buddha statues with a plaque bearing the owner’s names at the temple entrance. For a fee one can also get their car, home, or jewelry blessed or have prayers said for good health and wealth.

Shaolin Business Deals

In the late 2000s, Guandu, a town that has been absorbed by Kunming city, spent $3 million to rebuild the four temples to draw tourists but no one came. To draw visitors, Guandu officials struck a deal with business-savvy warrior monks of Shaolin. In exchange for managing the Guandu temples for 30 years, the monks will keep all proceeds from the donation boxes and gift shops. [Source: Andrew Jacobs, New York Times, January 1, 2009]

Andrew Jacobs wrote in the New York Times, “ Guandu officials say they will get no money from the deal, but they hope the Shaolin mystique will pull in the kind of crowds that have turned Shaolin monastery into one of China’s most popular tourist destinations. On Guanda official said the government would save the $88,000 once spent on temple maintenance each year. They are also counting on the tax revenue from a vast new mall that is nearing completion next to the temple complex.”

“The management deal has provoked howls among some Chinese, with many critics decrying the commercialization wrought by the Yongxin. Shaolin Chain Store, read the headline of one recent posting written on Sina.com, a popular Web site. There’s nothing wrong with chasing profits and fame, but they can’t use the name of Buddha.”

“Such sentiments are hard to find in Guandu, where people seem to enjoy the sudden uptick in tourism...A squadron of incense vendors surged around visitors, and the Liu family noodle shop was doing a brisk business feeding the famished. Before the monks came, the only people who came were old, and they didn’t spend any money, said Cao Jinbu, the shop’s owner. Wan Liqiong, who runs a trinket stand across from the temple gate, said she would probably have to switch some of her stock to include Shaolin-oriented souvenirs.”

“After reading about the Shaolin deal in his local newspaper, Ying Daojin made the eight-hour journey by bus just to catch a glimpse of the monks. A 30-year-old corn farmer from northeast Yunnan, Ying described himself as a nonbeliever but seemed willing to give religion a try. I’ve heard Buddhism can open your mind, he said wide-eyed as a monk glided by. Kung fu is also good for your health.”

“The Shaolin monks were decidedly unapproachable. The young men waved away inquiries. When one bespectacled monk found himself the subject of a photographer’s interest, he grabbed the camera and then offered a menacing martial arts pose when his demand to have the picture erased went unmet. Negotiations proved fruitless, and the pictures were deleted. The monk bowed, smiled and walked away. Others were busy helping to renovate the gift shop while another group of monks was handling the bequest of an adherent who had stopped by bearing gifts.

A few days after their arrival, the monks taped a handwritten poster at the temple entrance advertising kung fu lessons. The cost: $44 for a month of instruction, nearly a full month’s wage for some Chinese workers. The security guard at the front gate said the classes were selling well, with more than 100 people already signed up. He showed off the student roster, most of them children and teenagers. Everyone loves the Shaolin monks, he said with a smile.” Yongxin, who drives a Land Rover and has established Shaolin branches in Italy, Germany and Australia.