Buddhist Ceremonies in the Mongolian Capital City Before the Communist Repression and After the Revival by Krisztina Teleki

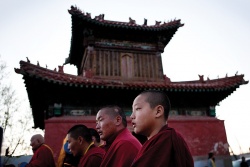

Editor’s introduction: Buddhism in Mongolia has had dramatically different turns of fortune during the last century. Buddhism was firmly entrenched and expanded significantly during the decade of Mongolian independence beginning in 1911; it was severely repressed, with tens of thousands of monks and lamas executed and temples destroyed, during the late 1930s; and then, since the early 1990s and the end of Soviet socialist influence, it has significantly resurfaced and been reasserted. Remarkable in this context has been the post-socialist occurrence of elderly monks of 70, 80, or 90 years of age teaching from memory near-forgotten Buddhist texts and practices to post-socialist teenagers and young adults 50 years or more their junior.

Given this context, the present findings of Dr. Teleki concerning the continuity of pre-repression and post-repression Buddhist rites and ceremonies in Mongolia is extraordinary. Her detailed archival, oral history, and contemporary ethnographic investigation here reveal the great extent to which the large and complex calendrical corpus of Buddhist liturgical rites, commemorations, and festivals that were evident in the capital’s monasteries and elsewhere until the late 1930s are now to a surprising degree re-established and reasserted in the capital’s monasteries, often with great exactitude.

This accomplishment is underscored and thrown into relief by the challenges that Mongolian Buddhism presently faces, both economically and in its relatively small number of monks and lamas, as well as by religious competition from Christianity and from increasing secular and/or capitalist values. While these challenges are often large, the ability of Mongolian Buddhism to re-establish its key rites and practices following seventy years of anti-Buddhist socialist repression is testament to the dedication and devotion of core practitioners, old and new, and to the deep-seated cultural significance of Buddhism in Mongolia.

The aims of Mongolian Buddhist ceremonies are to pray for the benefit of the Buddhist faith and all sentient beings, to annihilate their internal and external obstacles, and to help achieve a favorable rebirth and enlightenment. The aim of my present paper is to portray Buddhist ceremonies that were held in Ulaanbaatar until 1937, as well as ceremonies that were revived after 1990.[1]

Destruction and Revival

In Mongolia prior to the systematic destruction of monasteries during the late 1930s, approximately 1,000 monastic sites were in existence. Urga – also called Ikh khüree, Daa khüree, Bogdiin khüree, or other names – was the biggest monastic camp (khüree) and was the centre of the Bogd (or Jawzandamba khutagt, T. rje btsun dam pa) lineage until 1924. Gelukpa (Yellow Stream) teachings dominated in its temples, of which there were approximately 100. The eastern monastic district had approximately 45 temples, Gandan had ten temples, and there were two large monasteries (Dambadarjaa and Dashchoinkhorlin) and a meditation retreat (Shaddüwlin) to the north. In the quarters serving the lay population, Gelukpa and Nyingmapa (Red Stream) temples were located.[2]

Concerning Buddhist ceremonies, the descriptions of A. M. Pozdneev,[3] archival materials, photos, and oral history offer invaluable sources. Daily chanting was held in the main assembly hall and monthly and annual festivals made religious life eventful. All ceremonies were brought to a halt in 1937. Although Gandan was partially reopened in 1944, the majority of the old religious practices could be revived only after the democratic changes of 1990. The old monks, some from before the purges, fulfilled a principal role in the revival through the teaching of texts, music, offerings and monastic rules to disciples. Today more than 40 temples are functioning in Ulaanbaatar, of which more than 30 follow Gelukpa teachings.[4] Among them Gandan, Züün Khüree Dashchoilin, and Betüw monasteries are the largest with a large variety of ceremonies. Small temples do not have such expansive ceremonial life; they have fewer monks, and devotees and donations or revivers of tradition are sparse.

Daily Chanting and Annual Festivals, Once and Again

Though Mongolian ceremonial language and ceremonies originated in Tibet, the daily chanting of prayers has differed from the Tibetan practice, as it consists of several prayers, including ones written by eminent Mongolian lamas. The daily chanting of prayers has been revived in almost all monasteries.[5] The 8th, 15th and 30th days once had great importance in the monthly ceremonial system of the old main assembly hall. Today monthly ceremonies are held on the 8th, 15th, 29th and 30th days.

As for annual ceremonies, the biggest festivals historically attracted numerous laypeople to Urga. The great Maitreya Festival, celebrating the future Buddha, Maidar (T. byams pa), which is now held in the first summer month, was one of the most spectacular events of Urga according to Pozdneev (1971, pp. 54-55.). The ceremony itself is called Maidariin chogo, or Jambiin chogo (T. byams pa’i cho ga). All the lamas and the lay population gathered in a procession around the monastic quarter following the statue of Maidar, carried on a huge cart with a green horse head. This festival was called Maidar ergekh (“circumambulation with Maitreya’s statue”). There was another kind of recitation dedicated to Maidar (Maidariin düitsen ödör) on the 6th of the last summer month with a Jasaa Jambiin chogo ceremony. Today, it is performed, again in Gandan and in Züün khüree Dashchoilin monasteries, as well as in some rural monasteries, to hasten the coming of the future Buddha.

Another significant event has been the Tsam (T. ‘chams) religious dance, performed in summer with the participation of nearly 100 lamas. The aim of the dance is to conquer the enemies of the Buddhist faith, as well as to bring prosperity and wellbeing to the spectators. The monks of Züün khüree Dashchoilin monastery in Ulaanbaatar have been successful in reviving this demanding tantric practice.

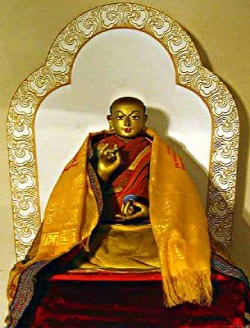

The Danshig (or bat orshil, T. brtan bzhugs) ceremony was held for the longevity of the Bogd (the c. Today, it is performed only on special occasions, such as the commemoration festival of Öndör gegeen Zanabazar (1635-1723), or acknowledgements of young reincarnations of famous saints (khutagt khuwilgaan). Preceding the Lunar New Year, Tsagaan sar, ceremonies lasting for three days were held in the main assembly hall to honor the wrathful deities, and the Sor (T. zor) fire offering was performed to remove harmful forces and prevent natural disasters. Tsederlkham (T. tshes gtor lha mo), the yearly ceremony of Baldanlkham goddess (T. dpal ldan lha mo, Skr. Çrídeví), was performed in all temples at the dawn of the New Year to pray for favorable circumstances for the coming year. Though today the three-day long ceremonies called Khuuchin khural are performed only in a few locations, the Tsederlkham ceremony is held in each temple of the capital city as well as in the countryside to greet the Lunar New Year.

The four great festivals of Buddha, the commemoration of Tsongkhapa (1357-1419), the founder of the Gelukpa tradition, and that of Öndör gegeen Zanabazar, the key figure responsible for the diffusion of the Gelukpa tradition in Mongolia, were held in nearly every temple. This is also the case today.[6] Today four ceremonies are held as “great days” of the Buddha (Burkhan bagshiin ikh düitsen ödör), called Tüwiin chogo (T. thub pa’i cho ga) or Burkhan bagshiin chogo. All of them bear individual names referring to their purposes. In Urga, the New Year started with a special ceremonial period called the Great Prayer Festival (Yerööl chenbo khural, T. smon lam chen mo; or Tsagaan sariin doodbii/dudba(i) T. bstod pa; or shortly, Yerööl, T. bstod pa; or Choinpürel jonaa, T. chos ’phrul bco lnga). These ceremonies lasted for 15 days in the datsans, in some aimag temples, and in the main assembly halls of Gandan, Dambadarjaa, and Züün Khüree.

Another great festival day of the Buddha is on the 15th day of the first summer month, which commemorates his birth, the day he reached enlightenment and became a Buddha, and the day when he passed away (T. mngon par byang chub pa’i dus chen). The third festival of the Buddha is held on the 4th day of the last summer month. It commemorates the day when Buddha first preached the Dharma, often referred to as “the festival of his first turning of the wheel of Dharma” (Choinkhor düitsen, T. chos ’khor dus chen). Both of these ceremonies must have been held in the main assembly hall of Züün Khüree. Pozdneev mentions one of the Choinkhor düitsens (1971, pp. 54-55.) that was held on the 4th of the last summer month. The next festival on the 22nd day of the last autumn month is called Lkhawawiin düitsen (yerööl) (T. lha las babs pa’i dus chen). It is the day when Buddha descended from the Gods’ realms, where he had spent ninety days teaching and spending the Khailen (T. khas len, “oath-taking”) retreat. In the monastic schools, Lkhawawiin dom (T. lha las babs pa’i ston mo) was held on exactly the same day, and this event was also commemorated in some aimag temples. On the 25th day of the first winter month, the anniversary of Tsongkhapa’s passing, called Bogd lamiin düitsen yerööl, Bogd Zonkhowiin düitsen yerööl, or Zuliin düitsen, was held. Today it is called Zonkhowiin düitsen, Bogd lamiin düitsen or, as often referred to, Zuliin 25, “the 25th day of butter lamps,” reflecting the tradition of lighting butter lamps and burning incense sticks in honour of Tsongkhapa.

One of the longest celebrations was the oath-taking retreat period (Khailen or Yar khailen, T. (dbyar) khas len, “(summer) oath-taking,” also called Yarnai, T. dbyar gnas, “summer retreat”), which began on the 15th of the last summer month and lasted for 45 days. Only fully-ordained monks and novices were allowed to take part in this retreat, during which they read the Vinaya, confirmed their vows, confessed their possible mistakes and amended them. Today, it requires the participation of at least four fully ordained monks. Sojin (T. gso sbyong, confession of sins, purifying and confirming vows) was a part of this ceremony. On the 15th and 30th day of every month Sojin was held in the main assembly hall of Dambadarjaa monastery. Today, the practice of Sojin has hardly been revived, as fully ordained lamas are few in number. Circumambulation of the volumes of the Kanjur (Ganjuur, T. bka’ gyur) and worship of owoo mounds were held near Urga. These traditions have been revived on a smaller scale.

Sources of Ceremonies held in 1937, and Present-day Practices

Sources of information on ceremonies held in Mongolian monasteries are extremely rare. However, the National Archives of Mongolia preserves lists of ceremonies of Urga’s 28 Gelukpa temples.[7] They were all compiled in 1937 on the order of the Religious Authority (Shashnii zakhirgaa), including the names, dates, duration, number of required monks and actual participants of 623 ceremonies, which were held in and until that year. These valuable documents are unique sources not only because they indicate how many monks belonged to certain temples before the closure of the monasteries but because they also demonstrate the lively religious life of the temples. According to our present knowledge, such sources are quite rare in the history of Ulaanbaatar, reaching back over 300 years.

Among the data concerning the 28 temples one can find descriptions of the main assembly hall (Gandantegchenlin) of Gandan monastery and its three relic temples (total 31 ceremonies) and two philosophical schools: Güngaachoilin datsan (42 ceremonies) and Idgaachoizinlin datsan (35); Khailan jas (3); the medical monastic school (17) of Züün Khüree as well as its 22 aimag[8] temples, namely Jadar (10), Toisamlin (23), Tsetsen toin (23), Dashdandarlin (17), Jas (20), Nomch (15), Sangai (16), Zoogoi (29), Dugar (14), Mergen khamba (12), Biziyaa (11), Khüükhen noyon (10), Darkhan emch (16), Erkhem toin (23), Wangai (48), Barga (7), Namdollin (26), Bandid (13), Jamiyaansün/Choinsün (25), Lam nar (17), Mergen nomon khan (15), Örlüüd (25) as well as the ceremonies of Dambadarjaa monastery (90). From these data we can gain a complex picture of Gelukpa religious life in the city. What follows here are a few examples of these ceremonies.

As for everyday practice, Tsogchin (T. tshogs chen) recitation was held in the main assembly halls, while in other temples the regular service of Jasaa was read by a few monks. (Jasaa means temporary service, family adoration, or regular activity.) Today Tsogchin has been revived almost everywhere, and in the biggest monasteries Jasaa consists of four lamas who do the recitals requested by individuals every day. In several temples in Urga, Jasaa Sakhius, Jasaa Tsedew, or other Jasaa ceremonies related to the cult in the given temple were performed daily by pairs of lamas (two, four, eight, and so on). San (T. bsangs) incense offering, a purification ritual, was performed every day in a few temples, sometime with dallaga practice (T. g.yang gugs, ritual for summoning the forces of prosperity). Moreover, in certain temples there were daily rituals such as Namsrain san (T. rnam sras bsangs), Maidariin san, often with sacrificial cake offerings (dorbul, T. gtor ‘bul) and demberel (T. rten ‘brel). These rituals exist today as well.

Apart from Buddha Çākyamuni and Tsongkhapa, the highest religious dignitaries such as the eight Bogds were commemorated annually. This kind of Düitsen yerööl (düitsen, T. dus chen, “great day, festival”) or Daichid/Daichod yerööl (T. ‘das mchod, “death anniversary, commemoration”) ceremonies took place in each temple. The two terms are used inconsistently in the texts. These ceremonies consisted of praises and eulogies (yerööl, magtaal). Concerning the local dignitaries, on the 14th of the first spring month, the great feast day of Öndör Gegeen Zanabazar (today known as Öndör gegeenii ikh düitsen ödör) and the ceremony called Öndör bogdiin düitsen yerööl or Öndör gegeenii düitsen yerööl, Tsagaan sariin 14-nii yerööl, or Tsagaan sariin yerööl, or simply Yerööl was held. The lamas commemorated his beneficial deeds and his passing away.[9] As for his further incarnations the great feast day commemorating the 2nd Bogd, called 2-r bogdiin düitsen yerööl was performed on the 17th day of the last winter month. The commemoration of the 3rd incarnation was held on the 21st day of the last autumn month, whilst that of the 4th incarnation took place on the 16th day of the middle winter month. The 5th Bogd was commemorated on the 3rd day of the first winter month. The 6th incarnation’s ceremony was held on the 20th day of the first winter month, and the 7th incarnation was worshipped on the 12th day of the middle winter month. Apparently these ceremonies were held only in Wangain and Lam nariin aimags, whereas the commemoration of the 8th Bogd was held in several temples on the 17th day of the first summer month.

Today, only Öndör gegeen’s prayers are recited on the 14th day of the first spring month, the others’ cults have not been revived.[10] Furthermore, some other dignitaries’ commemorations were held in few temples, such as that of Khachin lam (T. mkhan chen bla ma), which was held on the 7th day of the middle winter month in Süngiin aimag. The ceremony honouring Jalkhanz khutagt (T. rgyal khang rtse, one of the main incarnation lineages in Mongolia) was recited on the 9th day of the middle summer month in Wangain aimag, and the ceremony in honour of Yonzon khamba was held on the 7th day of the middle winter month in Wangain and Erkhem toinii aimags. The commemoration of the 8th Bogd or Bogd khaan (1870-1924) was held in several temples. Today this ceremony is held only in Gandan.

Ceremonies to worship the wrathful protectors were held often during the year. Each temple had an image or a sculpture representing its own tutelary deity (yadam, T. yi dam), and protector (sakhius, T. bstan bsrung). Nowadays, on the 29th day of each month the protectors are worshipped in the framework of a ceremony, called Sakhius or Khangal. In Urga various rituals were held for their worship such as the ceremony dedicated to all the ten wrathful protectors, called Arwan khangal. The ceremony is held to protect all sentient beings and the lama community from any hindrance.

Ceremonies were performed in honour of the nine protectors (9 khangal), the six protectors (6 khangal), or only one or two of them such as Lkham or Gombo, Gongor and Namsrai. On some of these occasions, called Sakhius danragt or Khangaliin danragt, thanksgiving offerings (danrag, T. gtang rag) was made to the deities, sometimes together with dügjüü offerings (T. drug bcu). Among them, Choijal dügjüü or Choijoo dügjüü was and still is the most famous one dedicated to Choijal (T. chos rgyal, Skr. Yama), the Lord of Death. An important ceremony to worship the wrathful deities was Danshig(iin) khangal (T. brtan bzhugs) held for 3-4 days in the middle winter month in several aimags of the city. Furthermore, Dergediin khangal additional and/or assistant protector ceremonies were held in a few aimags. Tümed khangal or Tümed sakhius was another type of ceremony performed for the protectors. As it is clear from the archival material this ceremony was surely held in Güngaachoilin datsan. Ikh sakhius (“Great Protector”) ceremony was held in almost every temple on different dates that related to their protectors and traditions.

Tutelary deities (mainly Buddhas and Bodhisattvas) such as Avalokiteçvara, the Bodhisattva of compassion, and Tārā, the saviouress, served as a basis for several practices of lamas. In a few temples sand maóðala (dültson, T. rdul tshon) of their tutelary deities were prepared. Today, only the Kālacakra maóðalas is prepared every year in Gandan. Chogo (T. cho ga) meaning “ritual, ceremony, way of performance” is a collective name for certain kinds of bigger ceremonies dedicated mainly to Buddhas, Bodhisattvas, and other tutelary deities. These rituals required initiation in the cult and practices of the given deity. As for the Buddhas, Awidiin chogo with the aim of clearing away all sins and praying for the deceased to gain rebirth in the paradise of Amitābha Buddha, was performed, as well as Ayuushiin chogo, worshipping Amitāyus, the Buddha of Boundless life. As for the Bodhisattvas Dar’ ekhiin chogo honouring Tārā, and Janraisegiin chogo (T. spyan ras gzigs kyi cho ga), the worship of Avalokiteçvara were performed. The ceremony in honour of the sixteen arhats or main disciples of Buddha (Naidan chogo) was also held. Today it is a usual ceremony held on the 30th day of each month.

Apart from the festivals described above, there were numerous other religious practices and events. As it is evident from the sources Nünnai or Nügnee/Nügnei (T. smyung gnas, “fasting ritual”) was held from time to time by a small number of lamas. This was a fasting ritual, fasting practice or retreat lasting for 3-15 days focusing on Avalokiteçvara, Vajrapāói, Akåobhya (Mintügwa yadamiin nünnai) or the Medicine Buddha (Manaliin nünnai). Dörwön tsagiin nünnai (“seasonal fasting”) and Jasaa nünnai were also held in few places. Today, if they wish, monks may fast individually. Fire-offering, called Jasiin galiin takhil(ga) was held in almost each temple on the 24th, 25th, or 26th day of the last winter month by two, four, or more appointed lamas. Its aim was to purify the financial unit and the treasury.

On the 25th day of the last summer month, the ceremony called “Consecration on the fortunate day” (Dashnyam arawnai, T. bkra shis nyi ma rab gnas) was held in Wangain aimag. Today, this is called ‘the Great Consecration’ (Ikh arawnai), and on this day all the objects of worship, statues, painted scrolls, and the shrines are re-consecrated in Gandan with the aim of renewing the effects of the original consecration.

Khajid (T. mkha’ spyod) ceremony was held on the 10th day of each month by four appointed lamas in the relics temple of the 5th Bogd. Today, in a few Mongolian monasteries, including Gandan, the Khajidiin chogo ceremony is held only once a year. However, in some temples, especially in Red Stream temples, it is held monthly on the 25th and the 10th days of the month. Narkhajid (T. na ro mkha’ spyod, Skr. Sarvabuddha dākini) was the main tutelary deity of the 5th Bogd. It is said that when he was meditating on this goddess, he saw a red light above the Bogd Khan Mountain and the River Tuul. Thus, this ceremony has been held ever since then.

Ündes (T. rgyud, ‘tantra’) ceremony was held not only for the wrathful deities, but for Tārā, and other deities as well, and sacrificial cake offering (dordow, T. gtor sgrub) could be made to them (e.g. Gürgüliin dordow). The ceremony of Günreg (shortly for Günreg Nambarnanzad, T. kun rig(s) rnam par snang mdzad, Skr. Sarvavidyā Vairocana) for the deceased was held regularly at the request of individuals.

In Toisamlin aimag on the 15th day of every month the Guhyasamāja tantra (Sanduin jüd, T. gsang ’dus rgyud) was recited. Today, in almost each temple Guhyasamāja tantra is recited on this day. (Gandan lamas preserved the ceremonial rules of the old Jüd datsan.) The Mongolian Sandui was recited in Gandantegchenlin twice in winter until 1937 according to the text.

A special practice called Bumbiin takhilga (“vase offering”) such as Gongoriin bumba, Namsrain bumba, Jambaliin bumba, Manaliin bumba was performed in a few temples. Ganjuur ceremonies were held infrequently and only in a couple of temples.[11] Tsogchid offering ceremonies (T. tshogs mchod, Skr. ganapūjā, “accumulation of offerings,” feast offering) were also performed to honour wrathful deities. Donchid (T. stong mchod, “thousand-fold offering”) was performed for several deities. Büteel is a ceremony with the recitation of the magic formula of a given deity several times. In philosophical monastic schools Migzemiin büteel (T. dmigs rtse ma) and Janraisegiin büteel were held for six days in the middle summer month with the participation of hundreds of lamas, whilst in other places these were recited randomly for a day by a few of lamas. Today, this ceremony is called Maaniin büteel. It is dedicated to Janraiseg and to achieve a healthy and peaceful life. In Urga Dar’ ekhiin büteel, Choijingiin büteel, and Gürgüliin büteel were held as well. Ceremonies of the Medicine Buddha (Manal) were mostly held in the Medical monastic school. There were several types of ceremonies related to Manal.

The Gürem (T. sku rim) ceremony (today called also as zasal) was a usual practice including healing or protective rituals. Günreg ceremonies were held to elevate sentient beings from unfavorable rebirth to a better one, and to save them from any inauspicious rebirth. Jadamba (T. brgyad stong pa, Eight thousand verses version of Prajñāpāramitā) was read in Dugariin aimag.

In philosophical monastic schools several dom (T. sdom) were held in winter: four ikh dom and four baga dom. Their names refer to the day when they were held, such as 18-nii dom, 19-nii dom, 20-nii dom, 21-nii dom, 25-nii dom. Their majority was held on great days of the Buddha. Moreover, Gawjiin damjaa (T. dka’ bcu’i dam bca’), (Parchin) Domiin damjaa (T. phar phyin ston mo’i dam bca’) were held there as well as debates on the five volumes of philosophy (Tawan bot’, or Daj ergekh). Joroo,[12] Jüshii/Züshii dom (T. bcu bzhi) are also mentioned as well as Lkhawawiin düitsen yerööl or Lkhawawiin dom, and Lyankha dom or Lyankhiin dom. According to Soninbayar[13] before the dom exams (domiin damjaa), the lamas who studied in the dom classes were ordered to participate in the given feasts of the four great dom (ikh) and the three small dom (baga).[14] Today, philosophical exams can be taken only in the Dashchoimbel monastic school of Gandan monastery.

Seasonal ceremonies were held in some temples as well, such as Namriin dund sariin khural (“ceremony of the middle autumn month”), Khawriin süül sariin khural (“ceremony of the last autumn month”), Öwliin tergüün sariin khural (“ceremony of the first winter month”), Öwliin dund sariin khural (“ceremony of the middle winter month”), Öwliin tergüün sariin 25-nii yerööl (Yerööl ceremony on the 25th day of the first winter month), and Arwan tawnii danrag (“thanksgiving offering on the 15th of the month”). Sariin chogo or Sariin khural (“ceremony lasting for a month”) or Namriin neg sariin khural (“ceremony for a month in autumn”) were also held in some temples.

Although the archival sources do not include data about Nyingmapa temples, we can assume that their practices were similar to the present-day temples (about ten in number) which practice worship to Padmasambhava and the dākinis, thus, on the 10th and 25th day of the month, ceremonies are held in their honor.

Connections with Devotees

There is an important issue that is not mentioned in the written sources. From the archival sources we can see how busy religious life was in temples in the city until the beginning of the massive persecutions in the late 1930s, and in the 1990s we could witness its revival personally. Thanks to the enthusiastic old lamas and pious devotees we can again see the Maitreya procession, the Tsam masked dance, and several other ceremonies. At present we can observe how temples maintain their traditions and develop ritual practices. Apart from the large variety of ceremonies that are performed once again in temples, efforts made by monks in various other fields to support the everyday life of faithful devotees must be emphasized as well. Although in the recent years the reputation and number of monks has decreased in Ulaanbaatar, it now seems that monks who have remained in the community are making a tremendous contribution to the Buddhist faith and to the wellbeing of the community. Monks can meditate at home, receive more initiations, listen to religious teachings, and develop their personal knowledge as originally established by their old masters who have since passed away. Meanwhile, devotees can visit monasteries, give alms and offerings to monks, perform virtuous deeds, make prostrations, feed pigeons, light butter lamps, recite mantras with their their rosaries, turn prayer wheels, and express their gratitude in several other ways. Monks and devotees consecrate stūpas and worship owoos together. Devotees invite monks to their homes to perform rituals to liberate them from illness, bad fortune, hardship, and natural diseases. Monks also perform blessing of devotees’ new homes, in order for life to prosper there, animate new religious objects to protect them, and give advice concerning weddings, house moving, and other life-issues.

Though ceremonies have not been revived at such a large scale in the countryside as in Ulaanbaatar, the conduct of the monks is similar, and their reputation is generally better there. Apart from daily chanting, they have hardly been able to revive other ceremonies and cannot educate their disciples properly, as even the maintenance of their community is not ensured, due to the lack of constant income and the need to pay taxes.

The cooperation of monasteries seems to have been revived in a small scale, which is adequate in the development of religious practices. At the beginning of the 20th century Mongolian and Tibetan lamas of the capital city made short visits to rural monasteries to give teachings and support new practices. This occurs as well today, but only rarely. In recent years, reincarnations of Mongolian saints (khutagt khuwilgaan) have been acknowledged, which is also very important in supporting the faith of the lay public. We can conclude that due to the small number of monks, the reintroduction of all the old ceremonies is not possible. Religious practices will have to be developed one step at a time.

Bibliography

- Diwaasambuu, G., Gandantegchenlin khiid dakhin sergesen tüükh. Ulaanbaatar 2009 [History of the Revival of Gandantegchenlin Monastery].

- Jambal, B. – Mönkhsaikhan, D., Tsogchin unshlagiin zereg tus amgalan garakhiin oron orshwoi. Ulaanbaatar 2004 [Order of the Texts of the Daily Chanting Ceremony, The Source of Benefit and Happiness].

- Majer Zs., A Comparative Study of the Ceremonial Practice in Present-day Mongolian Monasteries. PhD thesis, Eötvös Loránd University, Budapest 2009.

- Pozdneyev, A. M., Mongolia and the Mongols, edited by Krueger, J. R., translated by Shaw, J. R. and Plank, D., Bloomington, Indiana University 1971.

- Pozdneyev, A.M., Religion and Ritual in Society: Lamaist Buddhism in late 19th-century Mongolia. ed.: Krueger, J.R. The Mongolia Society. Bloomington 1978.

- Soninbayar, Sh. (ed.), Gandantegchinlen khiid, Shashnii deed surguuliin khurangui tüükh Tsagaan lawain duun egshig khemeekh orshiwoi. Ulaanbaatar 1995 [Gandantegchinlen Monastery, Short History of the Religious College: The melody of the White Conch Shell].

- Teleki, K.: Monasteries and Temples of Bogdiin Khüree. Ulaanbaatar 2011.

- www.mongoliantemples.net/English

Sources of the National Archives of Mongolia’s Modern Collection (keeping their spelling)

- Kh193/42 without title [Annual ceremonies of the medical monastic school]

- Kh196/8 Gandantegčinling-yin dangsa [List of Gandantegchenlin]

- Kh199/55 Barγa-yin ayimaγ-un toγtamal qural-ud [Regular Ceremonies of Bargiin aimag]

- Kh200/21 Wanggai ayimaγ-un qural-ud nersiin bürtgel dans [List of Wangai aimag’s Ceremonies]

- Kh208/73 Duγar-yin ayimaγ-un nigen ĵil-dü toγtamal qurdaγ qural-yi todorqailaγsan küsünügtü [Data Sheet of Dugariin aimag’s Regular Ceremonies]

- Kh211/18 Ĵamyangsüren-yin ayimaγ-un nigen ĵilün toγtamal qural-ud-un neres [Names of Regular Ceremonies held in

Jamiyaansürengiin aimag]

- Kh216/44 Toyisamling ayimaγ-un büküi qural-un dangsa [List of all Ceremonies of Toisamlin aimag]

- Kh218/18 Mergen q.ambu-yin ayimaγ-un qural-un ungsilγ-a-un dangsa [List of Ceremonies held in Mergen khambiin aimag]

- Kh224/9 Örligüd-ün ayimaγ-yin 27 on-u toγtamal qural-un bürgüdel-e [Regular Ceremonies in Örlüüdiin aimag held in 1937]

- Kh240/1/2 27 on-u Dambadariĵiya keyid-ün toγtomal qural-un dangsa [List of Permanent Ceremonies held in Dambadarjaa monastery in 1937]

- SKh188/144 Güngaachoilin datsangiin neg jild khurdag khurliin nersiig todorkhoilson dans [List of Annual Ceremonies held in Güngaachoilin datsan]

- SKh189/2 Yidgg.ačoiĵingling dačan-un nigen ĵilün toγtamal quridaγ qural-un küsünüg-tü: [Data Sheet of Regular Annual Ceremonies of

Yidgaachoinzinlin datsan]

- SKh209/66 Ĵooγai ayimaγ-un toγtamal qural-un dangsa [Regular Ceremonies in Zoogoi aimag]

- SKh212/38 Namdolling ayimaγ-un toγtamal qural-ud [Regular Ceremonies in Namdollin aimag]

- TsKh227/48 without title [Regular Ceremonies of Erkhem toinii aimag]

Footnotes

- ↑ The present paper was written within the frame of OTKA PD 83465 project, which documents the Mongolian monastic capital city’s heritage.

- ↑ For details of the monastic capital’s monasteries and temples see www.mongoliantemples.net/English; Teleki K., Bogdiin Khüree: Monasteries and Temples of the Mongolian Monastic Capital (1651-1938). PhD thesis, Eötvös Loránd University, Budapest 2009; Teleki, K., Monasteries and Temples of Bogdiin Khüree. Ulaanbaatar 2011.

- ↑ Pozdneyev, A.M., Religion and Ritual in Society: Lamaist Buddhism in late 19th-century Mongolia. ed.: Krueger, J.R. The Mongolia Society. Bloomington 1978; Pozdneyev, A. M., Mongolia and the Mongols, edited by Krueger, J. R., translated by Shaw, J. R. and Plank, D., Bloomington, Indiana University 1971.

- ↑ For details of Ulaanbaatar’s present-day temples see www.mongoliantemples.net/English; Majer Zs., A Comparative Study of the Ceremonial Practice in Present-day Mongolian Monasteries. PhD thesis, Eötvös Loránd University, Budapest 2009.

- ↑ The texts of the daily chanting of Züün Khüree Dashchoilin Monastery were published in 2004. Jambal, B. – Mönkhsaikhan, D., Tsogchin unshlagiin zereg tus amgalan garakhiin oron orshwoi. Ulaanbaatar 2004.

- ↑ For details of the present-day festivals and ceremonies see Diwaasambuu, G., Gandantegchenlin khiid dakhin sergesen tüükh. Ulaanbaatar 2009; Majer Zs., A Comparative Study of the Ceremonial Practice in Present-day Mongolian Monasteries. PhD thesis, Eötvös Loránd University, Budapest 2009.

- ↑ For the title of the texts, see the Bibliography.

- ↑ Züün khüree had 30 aimags, i.e. districts inhabited by monks. All aimag had an own temple.

- ↑ Today, this ceremony is known as Dawkhar yerööl, “double prayer” referring to the fact that apart from the usual prayers of the Lunar New Year’s 15 prayers, on this day that of Öndör gegeen is also recited.

- ↑ In the present-day Gandan monastery on this day there is a ceremony called Uuliin lamiin chogo, when the ritual text for the 8th Bogd, written by Luwsan (T. blo bzang, known as Uuliin lam, ‘the lama from the mountain’), is recited.

- ↑ Today, on the 5th day of the last summer month, the Jasaa Ikh Ganjuur or Altan Ganjuur ceremony is held as one of the annual ceremonies performed only in Gandan.

- ↑ Exact meaning unknown. M. Ĵoroo, T.

- ↑ Soninbayar, Sh. (ed.), Gandantegchinlen khiid, Shashnii deed surguuliin khurangui tüükh Tsagaan lawain duun egshig khemeekh orshiwoi. Ulaanbaatar 1995, pp. 66-67.

- ↑ According to Soninbayar the four great feasts were the following: Lyankh dom which was held on the 4th day of the last summer month, on the festival day when Buddha turned the wheel of Dharma; 22-nii dom was held on 22nd day of the last autumn month; 25-nii dom was celebrated on the annual commemoration day of Tsongkhapa, and Jüshii dom was held on the 14th day of the middle winter month.

Source

Author: Krisztina Teleki

academia.edu