Buddhist monastic education: Myanmar

Before British colonial rule, Buddhist monasteries were the main education institutions in Burma/Myanmar. Until today, monastic schools, or monastic education centres as they are often called, have been the most important civil-society institutions bridging the accessibility gap in the state-run education system in government-controlled areas. While public schooling is not available in many rural regions, there is a monastery in nearly every village (UNESCO 2002). Monastic schools cater particularly to poor children, are free of charges such as enrolment fees and usually provide teaching materials such as books for free. Moreover, many monasteries serve as schools and orphanages at the same time.

Traditionally, monastic education is characterised by non-formal and lifelong learning. In this sense, it can be said to represent the unity of life and religion, which still exists in many rural regions of Buddhist Burma/Myanmar. In its pure and traditional form, monastic education can thus be considered fundamentally different from the formal secular education system, which considers education as a preparation for life rather than a form of life itself (Tin 2004). In British colonial times, the fight for the right to a distinctively Buddhist education—as opposed to the secular education system imposed by the British—constituted a significant part of the anti-colonial struggle (Zoellner 2007a). Contrary to pre-colonial times, however, in present-day Burma/Myanmar, a secular national education system exists, but fails to provide adequate services. In this context, monastic schools often provide not only parallel but complementary education models, and the line between informal religious and formal secular education has become blurred to some extent. Besides non-formal and religious education, a growing number of monastic schools have started to also teach children basic skills needed for secular life; some of them have meanwhile even become (partly) incorporated into the formal education system.

Today, three main categories of monastic schools can be seen: the first confines itself to imparting Buddhist teachings; the second is made up of monastic schools that consider it their main task to impart Buddhist teachings but which, at the same time, also teach children basic literacy skills (although these second-category monastic schools are unable to hold exams or to award their pupils certificates that are recognised by the government); the third are those that adopt the government curriculum, which means that they engage in formal education. According to official government figures, 1183 of these third-category monastic schools are recognised by the government in a kind of coeducation system. They seem to be registered with the MOE and the Ministry of Religious Affairs (MRA). According to the same source, these 1183 schools reached 158 040 pupils in the 2003–04 academic year (MOE 2006). If monastic schools are recognised by the government, their pupils also have the possibility of acquiring an officially recognised degree. They can do their final exams either at a government school or at their respective monastic school, which then, however, has to send the exams to the ministry responsible for marking and issuing the certificates.[12] For officially recognised monastic schools, a kind of bridging system makes it possible for pupils to change from monastic to government schools. If, for example, pupils complete the primary level at an officially recognised monastic school, they are sometimes allowed to do a special test. If they pass this test, they can gain acceptance to a government middle school. According to other official statistics obtained from a UN agency active in the country and which are largely consistent with the official source (MOE 2006) cited above, the majority of all officially recognised monastic schools teach at the primary or post-primary levels. Some, but much fewer, teach at the middle level.[13] Furthermore, two to five officially recognised monastic schools were reported to teach at the high-school level.[14] Moreover, various monastic education centres also engage in vocational skills training such as computer training activities. The figures cited here are likely to be incomplete due to the lack of reliable data, but they point to a remarkable tend: by providing secular education and professional skills to poor children, some Buddhist monks seem to deliberately try to bridge the accessibility gap that exists in the state-run education system.

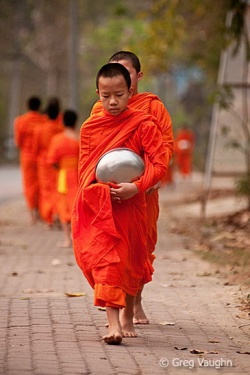

It should also be noted, however, that in terms of quality, monastic schools tend to show the same deficits as the state-run education system. For instance, learning is mostly by rote even though there are some important exceptions. Most monastic schools teach novices and lay children together and provide their educational services regardless of race and religion. Moreover, monasteries sometimes serve as protective umbrellas for more secular educational initiatives run by lay professional teachers or other lay volunteers (who may or may not have been trained). There are, however, also monastic schools whose main purpose is to counter similar efforts by the Christian churches and to prevent people converting from Buddhism to Christianity. This pattern is especially relevant with regard to those monastic schools that are also orphanages. Even though not all of the children they care for are Buddhist, some monastic orphanages require every child who wants to live in their compound to wear a Buddhist novice’s robe. Even in orphanages where this is not the case, Christian or Muslim children are sometimes encouraged to convert to Buddhism. Asked about the religion of his students, one monastic schoolteacher said that after living in the monastery for a while the boys normally became Buddhist. Another more critical dimension of monastic education relates to gender. Monastic schools cater mainly to boys (UNESCO 2002), especially those that, at the same time, serve as orphanages.[15] The author also visited some monastic orphanages that were run by Buddhist nuns and catered to girls, but these did not provide secular education such as literacy and numeracy. Moreover, most of them faced even more economic hardship than those monastic orphanages visited that catered to boys.

Monastic education centres vary in size and in the degree to which they are coopted by the regime. While some have only a few dozen pupils, others have between 100 and 800 (some big monastic schools have even more pupils, but they are exceptions to the rule). As a basic principle, the bigger an institution is, the more coopted by the State it tends to be. Small and rural monastic schools often centre on one individual monk and are more or less independent from government interference. Their capacities, however, are also often limited and their teaching materials quite basic (South 2004). In constrast, large monastic schools often have quite reasonable facilities and offer a number of secular subjects, sometimes even including foreign languages, particularly English. Some of the big monastic education centres visited could even afford to hire university students or professional teachers to give courses and had their own professional skills training centres or income-generating facilities such as tailor or carpenter shops. Such relatively large-scale functions come, however, mostly with a certain degree of cooption. For example, a general pattern seems to be that government officials pay public visits to the monastery and give (largely symbolic) donations in order to take some of the credit for themselves. Another aspect of cooption is that many of the monks who run big monastic schools have received their own education at the state-run Theravada Buddhist University, which operates under the MRA and which the government considers a tool to promote but also to ‘purify’ and control the Buddhist faith.

According to one expert on Buddhism in Burma/Myanmar,[16] the young monks who led the 2007 uprising came predominantly from the private monk schools, a specific type of monastery. Monk schools are purely religious education institutions, which cater to adult monks and impart Buddhist teachings on a tertiary—that is, college or university—educational level. They thus constitute a subtype of the first category of monastic schools depicted above. State-run and private monk schools exist, and the young monks who played a leading role in the 2007 demonstrations came predominantly from the latter. Nevertheless, by protesting against the government’s welfare policies and the fuel-price hike, these young monks certainly expressed the socioeconomic and political grievances of the whole Sangha and the population at large. (According to the same source, the demonstrations were so well organised because monks who belonged to the same monk school usually marched together in one block. Different monk schools could, in turn, coordinate their actions because young monks from different monk schools knew each other from their home villages and, before the demonstrations, called each other up.) In the aftermath of the uprising, the private monk schools have faced a harsh government crackdown and many of them have been abandoned or closed down.

Monastic schools, including orphanages, that cater to children are run mostly by a single monk or sometimes by a few (two to five) monks; they usually teach a certain number of young novices and an often larger number of lay children together. (In contrast, the monk schools usually host a fairly large number of already ordained monks.) To the author’s limited knowledge, these monastic schools did not play a role in the 2007 uprising. Nevertheless, as some academics and a local aid consultant from within Burma/Myanmar suggested, some of them might have been affected by the subsequent government crackdown. This is particularly likely for monastic orphanages that cater to older boys and that resemble the monk schools in their organisational structures and beneficiaries, especially as they often require all boys in their compound to wear a Buddhist novice’s robe.

So far, the role of the international donor community in promoting monastic education has been limited at best. While some monastic schools do receive funds and donations from international friends, such as travellers or small foreign NGOs, this happens largely on an individual basis. Except for a few notable exceptions, the cooperation is usually not institutionalised. The fact that hardly any Burma/Myanmar observers foresaw the 2007 uprising of the monks provides evidence that there is still a huge lack of information about the Buddhist monasteries and monastic schools and that further research is needed in order to assess their overall social and political impact.

[12] In the summer of 2006, several experts and monastic schoolteachers interviewed said that officially recognised monastic schools were registered with the MOE and that it was also the MOE to which all officially recognised monastic schools had to send their pupils’ final exams for marking. During another research trip in 2007, officials from the MOE itself claimed that all monastic schools were under the MRA. Contrary to that, a publication of the MOE itself claims the MOE and the MRA are in charge of the officially recognised monastic schools (MOE 2006:25).

[13] According to this second official source, there are 1158 officially recognised monastic schools, which altogether reach 161 492 children. According to the same source, 144 008 of these children are taught at the primary or post-primary level and only 17 484 are taught at the middle level.

[14] This information is based on various interviews conducted in Burma/Myanmar in the summer of 2006. While some of the people interviewed claimed that five monastic schools taught at the high-school level, others said there were only two. The author was able to visit one of them and read the funding proposal of a second one.

[15] There seem to be almost no mixed monastic orphanages in Burma/Myanmar. Of the ones I visited, only one catered to both boys and girls.

[16] The expert cited here specialises in Buddhism in Asia and is a lecturer at a European university, but has studied at a government university in Yangon for one year, still visits Burma/Myanmar frequently and maintains contacts with a number of monks and monastic education centres.