We are very pleased to share a guest blog by Ayesha Fuentes based on a presentation given at the International Association of Tibetan Studies 15th Triennial Seminar in Paris, July 2019.

How can prayer wheels, gtor ma (barley flour cake offerings), thang ka (meditational paintings) or skull bowls be understood as technological innovations? What is the relationship between how they were made and their cultural history, social value and/or ritual function? Tibetan ritual object types represents the transmission of uniquely conditioned material knowledge and skill, yet in both general and academic discourse technology is often placed in opposition to tradition when discussing culture: Where the former is perceived as forward-looking and experimental, the latter is assumed to be local, conservative or obsolete. Tradition, as an idiosyncratic expression of cultural identity, for example, needs protection and interpretation to be made a part of the modern world, whereas technology is often understood as scientific and universally accessible. Through a study of the facture and functions of Tibetan ritual objects, it can be demonstrated that tradition and innovation are in a continuous and dynamic relationship, and that what can be discussed as cultural technology is a material lineage of inventions, design, skills, construction and activation strategies that perform both social and ritual functions, and express the cultural tradition in which they have been designed and maintained.

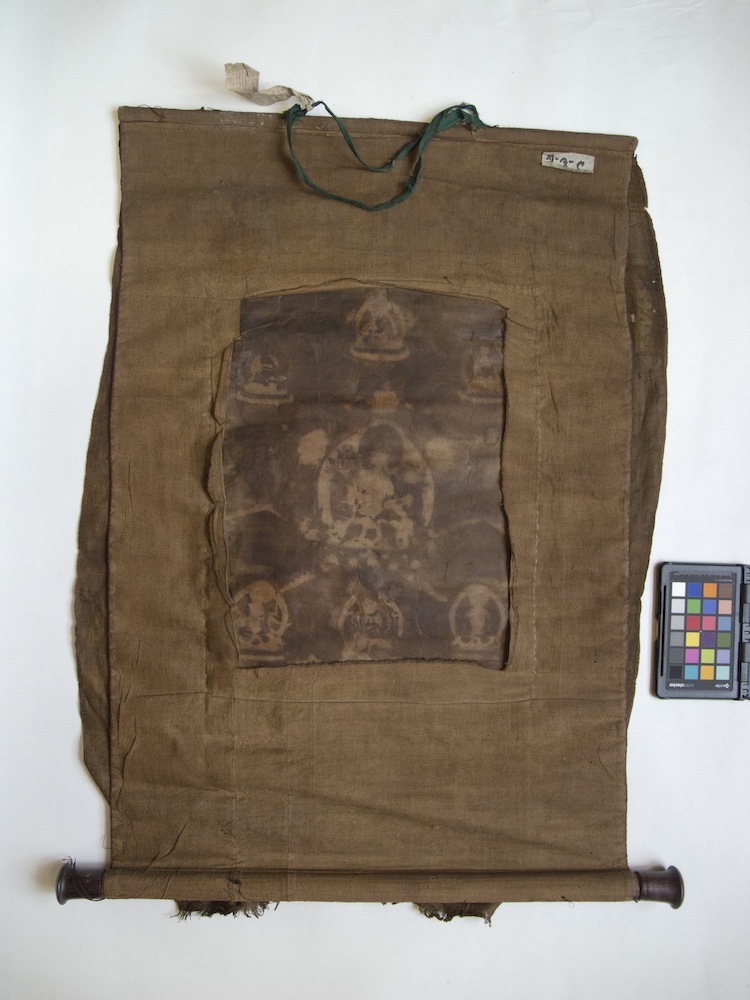

To date, the thang ka has been documented pre-dominantly as a representational object, and its technology is largely described in terms of its pictorial strategies though pigments, archaeometry or iconography. But the display and maintenance techniques of thang ka, and the history of their design and circulation in the Tibetan cultural region are less well explored. These objects are vulnerable to decay through pest activity, fire, water damage, smoke staining, and mechanical failure, but the material evidence for construction, alteration and use to which we have access in these objects is also valuable. For example, the flexible, composite nature of thang ka — where the painted central window is stitched between two layers of supporting textile, effectively framing it — facilitates the longevity of the image and its social and physical mobility. Thang ka moreover represent accumulated material and intellectual wealth; a long-term standard and program for visual literacy within the region; a tradition — as a lineage or continuity — of technical knowledge in the skills of thang ka construction; cycles for display, storage and even disposal in patterns often specific to idiosyncratic or regional traditions; and living objects with a modularity that facilitates their religious communal and social function through opportunities for material investment and the cultivation of merit through patronage, trade, gifting, and, once consecrated, as a platform for the presentation of offerings. As a scroll on a flexible substrate that is easily collapsed or expanded, thang ka are transportable and its mechanical components are relatively easy to repair: this is textile, not metal – stitching is not a specialist skill; there’s a bar for rigidity in storage and to provide weight on display. This portability and storability facilitates the circulation of religious information and pedagogical method, and also invites an interactivity common to tantric materials and Tibetan religious life. The thang ka is meant to be used and its logic of activation is relatively straightforward: the curtain, for example, closes and opens to protect the surface and cover the figure, when needed, and ribbons can be used to secure the object during storage or transport. These are functions obvious to anyone who has used a thang ka, but, as a cultural historian we can ask what is the longevity of those strategies and materials? What is the tradition of that design as a material strategy and what is its relationship to other ritual technologies?

Moreover, the activity inherent to the setting for the use of thang ka and other painted surface on display causes deterioration in certain patterns which are changing as new technologies and materials are integrated into production and display, and new functions for these objects develop. The historical precedent of using matte paint with gold highlights — for example here in a related tradition of wall painting — has been adjusted to incorporate new, brighter acrylic colors which are (at least initially) more vibrant under the electrical lighting increasingly used in both public and private religious spaces. These innovations in both infrastructure and pictorial technologies represent a potentially significant change in the consumption and production of the region’s material religion.

Alternatively, the use of human remains in Tibetan ritual objects — the subject of my doctoral research at SOAS University of London — can also be interpreted as a form of cultural technology, albeit one with very different narratives, technical accessibility and social value. The hypothesis of a “cultural ecology” for the relationship between the natural environment of the Himalayan plateau, the burial practice of scattering to the birds (bya gtor) and the incorporations of human remains into Tibetan religious life is an elegant frame for exploring the relationship between resources, ritual and cultural identity through material religion (Martin 1996).

This model can be expanded to consider regional variations in burial practices, the Buddhist valorization of physical evidence of saintly death, and the regional importance of tantra as a ritual strategy and relational vocabulary between humans and the landscape. Through my own research, for example, it can be seen that despite the introduction of modern incinerators, rural to urban migration and restricted trade, human remains are a vital and almost ubiquitous part of the region’s ritual vocabularies and daily religious life. At the same time, the commercialization of these objects — largely initiated by their exhibition in the mid-nineteenth century by British imperial cultural officers — has endangered them and made them difficult to obtain for practitioners and communities in the region.

The use of human remains in Tibetan religious life — both historically and at present — represents the accumulation of cultural narratives and a unique tradition in the creation of material culture. Even the collection and preparation of raw materials — that is, obtaining the bones from corpses — is marked by specialist training and a well-cultivated motivation, whether performed by a ritual specialist, monastic representative, or financial opportunist. Moreover, the techniques of shaping these materials reflect the diverse settings for these ritual practices, as well as the flexible social value of corpses in Tibetan and Buddhist communities as both a source of impurity and as platforms for the cultivation of religious knowledge or merit. In most communities, where a skull or thigh-bone is donated for use as a ritual instrument, it is subject to approval by a religious authority and judged according to a number of potential criteria: Was the donor an active Buddhist? Does the family of the donor approve? Are there any features of the skull which might disqualify it or enhance its value, such as self-arisen image, a fine color, or holes from the successful performance of pho ba? These are some of the various specifications suggested to maintain the techniques for ritually activating these objects.

Where ornamentation is added, on the other hand, this suggests a social economy through the introduction of other skills sets like shaping metal or carving bone. Material wealth is another indication of function, where a heavily ornamented object may be a gift or associated with a large monastic institution, whereas a simple bowl may be used daily to make offerings. Many other forms and functions are described in my forthcoming dissertation.

This suggested vocabulary of cultural technology is meant in part to address discrepancies in the interpretation and care of these objects in museums and collections, where I first encountered them. In my experience as a conservator, I saw in most cultural institutions an artificial distinction between representational objects as art and ritual instruments as ethnographic. Moreover, there is a tendency to interpret objects as demonstrations of material and intellectual wealth, rather than as examples of living social relationships and technological innovation. The two ritual material strategies discussed briefly here — thang ka and the use of human remains — are meant to suggest two possible categories of Tibetan cultural technology; several others could be suggested as well. My hope is that this perspective provokes a more rigorous conversation about the dynamic materiality of objects in Tibetan religious and social life, both historically and in terms of its continued innovation.

Ayesha is an objects conservator and PhD candidate at SOAS University of London, where she is writing her dissertation on the use of human remains in Tibetan ritual objects. For more information see www.ayeshafuentes.com.