DIFFERENT TYPES OF MAN

The fact that man as a concrete individual has always been of primary importance in Buddhism, has prevented it from accepting the idea that all men are equal. This, though often insisted upon with much rhetoric,

is obviously false not only where psychological aptitudes and talents are concerned but also where man's dealings with others are involved,

particularly in the field of education and learning. If equality has any meaning it only can suggest that man should act humanely, and even here a gradation in conduct is conspicuous.

Buddhism has always favoured a triple classification which has been developed on the basis of knowledge born of the desire to cultivate and

refine the personality and to achieve deliverance and spiritual freedom. It is true that the Buddhist classification seems at first glance to be of a rough and ready sort. Nevertheless its fundamental merit lies in the fact that it recognizes three main types as distinct, if not extreme, features of a continuous variable. It therefore takes into account

the rich variability and uniqueness of the human personality. Each man has an inferior, mediocre or superior nature, and each subsequent development or change from an inferior to a higher nature is evolved in the course of systematic training. 'Three types of man' is thus a term emphasizing the variability of the human individual.

Not only are there differences in intellectual capacity, the learning process itself also is not entirely a matter of intelligence as narrowly defined, for it involves emotional and social qualities of all sorts. This is particularly so in matters having to do with our symbol systems. Since these are basic to personality, it is clear that self-involvement must enter into most of our important acts, not only in the sense that it is necessary to be aware of how others see us but also of how we view our

selves. No process of learning is possible without a self-image, without the idea of how we are going to be. The triple classification evolved in Buddhism has this double aspect. In its determination of superior,

mediocre, and inferior natures it is concerned with how others see us, while regarding that which is done by each type it is concerned with how we view ourselves. Inasmuch as education and learning are graded processes, it will never do to skip any steps in them, unless one does not care whether the whole edifice that is going to be erected is shaky or not. It is here that the insistence of the Buddhists on their path being a graded course proves to be really sound. This path may be said to

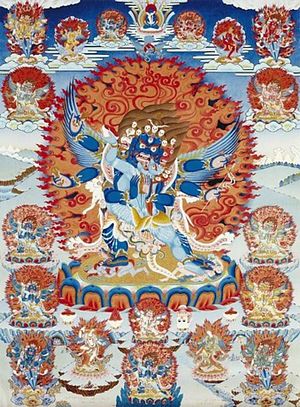

start with a few general principles and gradually, the further it goes, the more specialized it becomes until it finds its climax in what is commonly known as Tantrism. Even this latter aspect is a graded process open only to those whose intelligence and appreciation have been sharpened by the preceding courses. Therefore, if one pursues a self-determined concept of

training, and if one thinks that it will be sufficient just to pick out some item or other which suits one's momentary whim or which tickles one's curiosity, it can result only in absurd statements which, probably because of the lack of the proper perspective of the whole context, are never

theless held with authoritative fervour as valid. If a person were to practise religion on such haphazard information spiritual disaster would be bound to overtake him. At the lowest level we find the man whose sole aim is to emphasize his own happiness. Although he may adopt a sort of 'fleeting-hour' plan, in the back of his mind he is motivated by hedonistic ideas and action patterns

designed to ensure great and strong happiness for the major part of his life as opposed to long years of boredom and frustration. Since belief in the survival of the personality is common to most people, the above attitude lends itself admirably to the wish to pursue happiness after death. However, unlike most other survival theories Buddhism did not for a moment accept that survival entails the immortality of a soul. There is nothing everlasting and the fact that life continues does not prove that there must be some determinate factor which will continue unchanged.

This continual pleasure-hunting can be justified by two empirical facts: transitoriness through death and the misery of unhappy states. Transitoriness we can observe everywhere ; in the change of seasons, in the fleeting hours of day and night, in the passing away of those who are dear to us ... All this has an immediate effect on us. None of us can avoid death, which may strike at any moment.

The unhappy states, apart from that of animals, are symbolized by those who live in hell and the poor spirits. It is a fallacy to think that they are only unreal fantasies or, at best, aesthetic images. This may be

so for those of us who have developed the faculty of first speaking with

moral pathos about good and evil and then, when we ought to commit ourselves, avoiding the issues and leaping to the aesthetic, conjuring up pictures of illusory grandeur. But when and where the conception of

hells and spirits is indigenous it serves to formulate existentially experienced reality. The perception of hells and spirits means an active relation, be this a struggle against or a surrender to them. Admittedly, to us, the language which speaks of hells and spirits is for the most part outmoded, if not even meaningless, and its challenge entirely passes us by. The main objection is that the description of hells and of the spirits speaks of the transcendent in terms of an external and objective world, in which it can never be expressed adequately. The knowledge of hells and spirits can be existential only, in terms of that which is done to us and of our

responses and decisions. We do not now believe in hells and spirits and an objective revival is dangerous, but when we think deeply on matters of the spirit and of religion such expressions as 'to pass through hell' and 'to have seen a spirit' are not bad descriptions of ourselves and other people we know when in certain states. Certainly, hells and spirits

are elements of a mythic language, and we do not want to keep dead storypictures; but if they are symbols by which we can make the reality of religious experience more alive in ourselves, we cannot dispense with them. The language which refers to hells and spirits has an essentially material element in it, but its intention is not finally material. If it were so it would be mere idolatry, a sentimentality moving in aesthetic pictures. The Fifth Dalai Lama has succinctly stated the existential

significance of the idea of hells and spirits 1:

"The way of thinking which prevails nowadays consists in looking, as it were, at the misery of others from the viewpoint of an extroverted mind and in quoting a few scriptural texts; it is never a load on one's heart. For instance, when one sees the various preparations for the execution of a criminal in the king's court, it may happen that, pleased with the thought that justice

is done, feelings of disgust and thoughts of compassion arise. Usually, however, there is only joy over the spectacle. But if the man who is so pleased were to be led into court, fettered by chains, his joy would in a moment turn into thoughts of unbearable suffering and he would only think of how to become free. Hence, because of this similarity one must turn one's mind inward and meditate on this

misery of the whole world as affecting ourselves once we have been born in any form of the six kinds of life. "When the effect of evil deeds committed through hatred leads to a life in hell, there is at first the feeling of cold in the body, and when one

seeks warmth this state of feeling cold vanishes and instead one feels hot and is born in one of the fiery hells. Everywhere the ground is of glowing iron, the enclosure is red-hot iron, and in the midst of flames that leap up all around there is the so-called Reviving Hell. One has to imagine oneself as being born in such a place and one's body must feel agitated all over and one's mind frightened to excess. When one feels this one should think that many beings born there

assemble and in an orgy of hatred strike each other with various sharp weapons. One has to imagine this so clearly that one feels how one's body is cut into a hundred thousand pieces and how one is about to swoon. Revived by a voice from the sky which says : 'May you live once more', one must meditate again and again on the suffering of being pierced by swords. When this

experience is vividly felt and has a real effect on us, we lose all appetite for food and drink, we do not like idle talk and bustle, and quite naturally we set out to avoid evil and do good in all our ways of living. But if as a result the former mode of acting and behaving is not changed but remains as it was, religion and man become incompatible".

Here it clearly has been stated that the contemplation of the unpleasant states of life is not an end in itself nor a stimulus to action in the narrow sense of the word, but is something that reinforces action towards a goal which is pleasant. Two considerations enter here, man seeks certain experiences because they are pleasant and, still more so, because he needs them. Need is the key to a proper understanding of the place which the contemplation of misery occupies in the whole of man's life.

The unpleasant may be likened to a state of tension or disequilibrium which is so characteristic of the functioning of needs. Any form of tension, especially when prolonged, is decidedly unpleasant and its reduction by appropriate action is pleasant. The progress, therefore, is always in the direction of the pleasant. Similarly as the experience of hunger ('the need for food') is unpleasant, the state of a denizen of hell or a spirit deprived of anything that might end its suffering, is the recognition of a need in us, a need for peace and happiness which reinforces and supports the search for that which will fulfil the need.

The fact that the whole of mankind, as far as historical memory extends, has lived religiously, shows that religion has been a basic need and still continues to be so. Religion, as commonly understood, seems to have

I6

been intent on embodying its truth in tangible symbols and, in so doing,

upon transforming experienced reality into a system of propositions to be taken as literally true. In this development it has been contrasted with philosophy which pursues effective subjective certainty. Religion has symbolized the helpful forces and powers into gods and the evil ones into demons and the Devil, all of which for philosophy is but a medley of deceptive veils and misleading simplifications. Buddhism seems to be more on the philosophical side; it rejects the primitive belief in gods and demons, but as it developed it did not like the 'intellectual' try to kill the primitive within us.

In declaring that the helpful forces are found in The Buddha, The Dharma, and The Sangha, it does not create a new set of gods. It recognizes that man must come to terms with experienced reality by scrutinizing himself and the world much more critically and with much greater regard for facts than for the feelings tangled up with them. Taking refuge in the Three Jewels is the recognition that there is a way to secure happiness and peace, that man can take this way, and that on it he can find help as man to man. In other words, in the field of religious thinking Buddhism never loses sight of man's humanity.

It is important to note that in the whole of Tibetan literature taking refuge is linked with a critical attitude. One does not accept the Buddha or His teaching on mere credulity, but as a result of having examined critically the meaning of the term refuge. Only that which is itself not subject to fear can offer security and only that which is not harmful to others can be a reliable and satisfactory teaching leading to peace, happiness, and spiritual freedom. The [[Buddha and his

teaching]] fulfil these conditions and in this is found the root of the conception of the Buddha as an idea of man himself as he may become, rather than as an ideal which may break, and of the path becoming a self-disciplinary development of the personality towards the goal of Buddhahood. But this can be realized only at a much higher level of spiritual advancement. Therefore, the taking refuge is done at various levels of spiritual progress and each time the significance becomes more meaningful.

With the certainty that Buddhism does not demand of man that which he cannot reasonably do by himself, man has found a point of view from which he may look at himself and grasp the significance of the relation that holds between his actions and his feelings. Therefore, realizing that good or positive actions ensure happiness and that cruel deeds will bring unhappiness and suffering not only to others but to the perpetrator of the deed as well, man slowly feels the need to avoid those actions which

lead to unpleasant consequences. There are ten of them, three belonging to his body, namely murder, theft, and sexual misdemeanour; four to his speech, telling lies, slandering others, speaking words that hurt, and engaging in idle talk; and three to his thought, covetousness, wickedness, and wrong views such as those which deny the relation between the cause and effect of one 's deeds, which disclaim that by following the Buddhist path the goal is

reached, or which dismiss the idea of the Three Jewels. The avoidance of these actions is not a passive inactivity but entails a dynamic endeavour to act positively instead. Nor have these ten topics anything to do with commandments, which may or may not be broken with impunity. They are, rather, commitments based on the recognition of the dignity of the human person and deeply felt

sympathy for all living beings. Once man begins to think about the possible outcome of his actions, though it still be strongly self-centred, he has set foot on the lowest step of the ladder. He has become an 'inferior' being, inferior in the sense that he has not yet progressed far in his human enterprise.

It needs but little exertion to see that the situation which holds for ourselves can be made to account for the unsatisfactory state we observe everywhere in the world. To a sensitive person the suffering that exists in the world is almost unbearable. The picture of the world that has been developed in Buddhism, may not be 'scientifically' true. The question certainly can never be whether something is 'scientific', but only how it affects us and what is the message it wants to convey to us.

The truth to be brought home is that there is no end to suffering if we continue to be driven by our passions. The mythical language depicts in terms of the material the agonies of hell we experience when we succumb to hatred; the morbid craving for things made unattainable by depriving ourselves of the joys of what we have through our greediness and miserliness; the brutishness, ferocity and stubbornness through which we continue to plod on like beasts of burden and prey; the

demoniacalness of jealousy and the proud intoxication of godliness, which goes before a fall. This better than any other language reveals the fact that until our emotionality is tamed there will be no end to suffering and conflict. But taming one's emotionality does not mean to repress the emotions. This would only lead to a displacement of their energy and they would frustrate us in other equally destructive forms. To tame them means to recognize them for what they are, and in this

recognition they lose their power to take us unaware. Instead of being enemies they become our dearest friends. This transformation process is the theme of and the training that belongs to the period of following the graded path of Tantrism. On this lower r8

level, here, it means first of all to recognize the emotion together with that which makes it arise and then to counteract it by its opposite, the most effective one being to recognize that all emotions are ego-centred and that they become ineffective by the analysis of the nature of the 'I'. Such an analysis necessitates a higher training of the mind and it is here that the idea of interdependent origination finds its application. Just as the positive emotion of love is the best counteragent for

the negative one of hatred, so the understanding of relativity, of the concurrence of many circumstances and forces, is the best means to overcome the belief in a self as something that exists absolutely. It should be noted here that Buddhism takes a broader view of emotions than we usually do in psychology. Not only are there positive and negative emotions of

feeling, such as passion-lust and aversion-hatred, there is also an 'intellectual' emotion, an un-knowing. While for the Prasangikas every un-knowing is an emotion, the Svatantrikas distinguished between an emotionally toned un-knowing and an un-knowing not so toned. The content of the former

is the belief in the ontological status of an individual self, that of the latter of things other than the self. Belief in an individual self is, according to this distinction, plain wishfulness, that in things other than the self intellectual fog. The Prasangikas, on the other hand, considered every belief in an ontological status, be it of an individual self or of things other than the self, as wishfulness and emotivity, and that only the tendency to such a belief represented intellectual fog.

The conception of relativity is certainly an advance on the somewhat crude formulation of cause and effect as it pertains to one's actions when held on the level of the inferior person. As William S. Haas rightly remarks 1: u . .. only a superficial representation can interpret the relation between actions and their consequences, or between previous and actual existences and the succeeding ones, as determined by the law of causality. Since no soul-substance or anything else

substantial is assumed to exist, there is nothing which may be called cause, and nothing where causality could take its start. The relation between the karmatic tendencies or the erav ing which survive death and their concurrent appearances as rebirth cannot be conceived under the image of cause and effectJJ! It is with this 'world' -perspective that the status of a 'mediocre' man has been reached.

Having now emerged out of the most narrow confines of ego-centred-

1 The Destiny of the Mind. East and West. London, Faber and Faber, 1956, p. 209.

ness, man, by taking a broader view of himself in a world that owes most of its existence to his marking, can set out on the specific path of his humanity by realizing how his very nature reaches out to others. Therefore, whenever the Buddhist texts, be they those of the dGe-lugspas, bKa'-brgyud-pas, rNying-ma-pas or Sa-skya-pas, speak of the course for the superior man, they insist that the contemplation of whatever pertains to the inferior and mediocre types of man must precede any further attempt of self-development, for otherwise no solid foundation has been laid.

These four topics,

r. the uniqueness of human existence,

2. its transitoriness through death,

3· the relation between the cause and effect of one's actions, and

4- the general unsatisfactoriness of the world, serve as powerful stimulants to the practice of loving-kindness and compassion, when seen against the background of taking refuge in the Buddha as an idea of man, and in his teaching as the path of an inner spiritual development, and in the community of spiritually minded persons as friendly helpers. Indeed, if life is short and suffering is in abundance man must refrain from adding to the existing misery and do whatever

he can to alleviate and reduce it. Both loving-kindness and compassion, the one the intention that all sentient beings may feel happy and the other that all sentient beings may be relieved of suffering, serve as forces sustaining an enlightened attitude.

This enlightened attitude is more properly described as a radical change in outlook and a more marked goal-orientation, rather than a fleeting thought of enlightenment. It is usually qualified as 'supreme' or 'precious', and this determination is specifically Mayayanist. Unlike Hinayana the Mahayana always recognizes the striving of the Hinayanist, be he a pious listener or a self-

styled Buddha, and frankly admits that without them it would never have come into being. The readiness of the Mahayanist to take upon himself the responsibility of being active for others finds

its expression in the so-called 'perfections'. In a certain sense, however, the current translation by 'perfection' is wrong, because in its abstract sense of faultlessness it suggests the attainment of an ideal. There can be no doubt that ideals have been effective and have influenced our behaviour. This they have done when they were not images of fulfilment, but stimuli to man's desire to rise above himself. The original term, both

in Tibetan and Sanskrit (pha-rol-tu phyin-pa, paramita), always implies this reaching beyond ourselves and the transcending of our ego-centredness. It is therefore obvious that the development of these 'transcending' functions and operations could have originated only in the Mahayana which clearly realized that any form of self-centredness is a barrier to communication with others and, since man can find himself best through communication, it is also the greatest hindrance to gaining enlightenment as an awareness that is unbiased and unlimited in its cognition.

The 'six perfections', or, more properly speaking, the six transcending operations are closely related to each other. They are liberality-andgenerosity, ethics-and-manners, tolerance-and-patience, strenuousnessand-perseverance, contemplation-and-concentration, and discernmentand-appreciation. I have rendered each transcending operation by two related terms in order to bring out something of the

richness of its many meanings. These operations are subsumed under the two ideas of 'fitness of action' and 'intelligence', both of which must unite and constitute the Mayayanist path par excellence. In this conception we clearly recognize that consciousness is inseparable from action or attempted action. To be a thinking person is to have intentions or plans and to try to bring about an effect or achieve a goal. Inasmuch as action is connected with the development of an

enlightened attitude or marked goal-consciousness, it will be a help towards our understanding of the specific Buddhist conception when we remind ourselves that there is a kind of knowledge which is intentional and non-propositional and must not necessarily be expressed in verifiable statements. This intentional knowledge implies a certainty about the future

course of one's actions. Thus, to work for others (and to know how to go about it) is not a claim of any kind, but a declaration of one's intentions. This is the same as saying that I have made up my mind, and this implies that I have chosen between possible courses of action • 'Intelligence' - (the original term (shes-rab, pra}na) is very often translated by 'wisdom' as a sort

of wishful thinking) - which is the function which apprehends the real nature of things, always implies analysis, discrimination, appreciation, discernment, and that everything worth mentioning in the performance of an action was intended. As a consequence, 'fitness of action' (thabs, upaya) is not just expediency, that is, to do what seems easy, obvious or pleasant ; it signifies the best possible course of action in a particular circumstance because of the

knowledge of the actual situation. The unity of fitness of action and intelligence indicates integration which means that the diverse tendencies in an individual have become harmoniously united. Although it is possible to distinguish between 'fitness of action' and 'intelligence', one must not deal with them in isolation and forget the unity in experience. There is

hardly a Mahayanist text in which this union is not insisted upon: 'intelligence' alone is barren, it needs a moral frame, 'fitness of action' ; and the obverse is equally true. The development of an enlightened attitude and the practice of the six transcending operations belong to the level of the 'superior' man. It is the superior man who, if he is particularly gifted, can set out on the path of the Tantras which demand all that is in him and enjoin the strictest self-discipline. And in a certain sense he is bound to set out on this path because it is itself a necessary part of his freedom of thought.