Deity Meditation

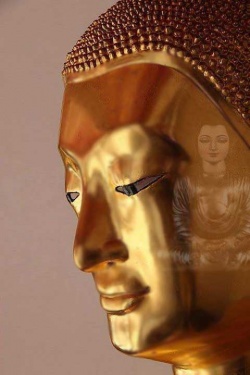

Sadhana practice is one of the most common and important forms of Tantric Buddhist ritual practice. It was practiced at the height of Tantric Buddhism in India and is practiced in all schools contemporary of Tantric Buddhism, Tibetan Vajrayana, Korean Milgyo and Japanese Shingon.

A Sadhana is a ritualised meditation on a chosen deity, or ishta-deva (yi dam); its mantra and the liturgy that goes with it.

Whilst there is a great variety of Sadhanas practiced, depending on factors such as lineage and classification of Tantra, they all are fairly similar in terms of contents and method.

This paper aims to explore how Sadhana is practiced in the Tibetan Vajrayana tradition. The basic premise of Tantric deity meditation is that it is a method for transforming ones ordinary perception of reality and ultimately experience and understand the nature of reality, or become enlightened.

Here it is useful to briefly mention a couple of doctrines which are essential to understanding Vajrayana practices.

Emptiness and Buddha Nature

Mahayana, and consequently Vajrayana, Prajnaparamita or perfection of wisdom literature, such as the Heart Sutra, The Diamond Cutter Sutra and other texts expound the teachings on emptiness or Shunyata (stong pa nyid).

The teachings on emptiness were codified and propagated by scholars such as Nagarjuna and others in the Madhyamika (u ma) philosophical school. A necessarily simplified explanation of Emptiness is that all phenomena are ‘empty’ of inherent independent existence and as such only exist in interdependence on other factors and phenomena.

This emptiness is not a simple nihilistic absence of anything whatsoever as clearly phenomena do exist on a conventional or relative level according to our everyday sensory experience.

This everyday experience of the world could be said to have its basis in conceptual and dualistic intelligence.

With this conceptual and dualistic approach to the world comes suffering in all its forms. Once ultimate reality is understood on a deep level, rather than a purely intellectual one, suffering ceases.

The enlightenment of the Buddha is simply understanding things how they actually are, rather than how they appear, whilst at the same time not being separate from it.

This ultimate non-differentiation between Buddha and seemingly unenlightened beings is essential to Vajrayana, as it gives a doctrinal basis for Buddha Nature.

The Buddha has said that all beings possess the essence of Buddhahood because the buddhajnana has always been present in all beings, the immaculate nature is non-dual and the Buddha-potential is named after its result. Asanga

Buddha Nature is the belief and doctrine that all sentient beings have the potential to become Buddha. So key to Vajrayana practice is this doctrine, that Gampopa entirely devotes the first chapter of the Jewel Ornament of Liberation to it, describing it as the ‘Primary cause’ of enlightenment.

Considering the importance of Asanga in the Karma Kagyu (karma bka' brgyud), it is interesting to note that he quotes from a number of Sutras to support his argument, but does not quote Asanga in this chapter.

The potential to become enlightened as espoused by the doctrine of Buddha Nature is understood somewhat differently depending on the tradition, where many Mahayanist would see the path to enlightenment as being a very long process, whereas Vajrayanists believe enlightenment can be realised in a single lifetime through the utilisation of methods such as deity Sadhana practice.

The theory behind deity meditation in Vajrayana is that the yogi can access his true nature, thus understanding the nature of reality and be freed from the dualistic ignorance which keeps him in conditioned existence or samsara ('khor ba).

Misunderstanding this reality, we wander endlessly in the cycle of existence.

The disciple must be introduced to the realisation of the true nature of his or her mind by a competent master, and then must meditate. When the disciple effectively reaches this recognition, the waves of the mind are reabsorbed in the immensity of primordial awareness.

It is realisation of Mahamudra ([[phyag rgya [chen po]]) or Maha-Ati (rdzogs pa chen po), the union of intelligence and emptiness, to which the phase of completion leads. Kalu Rinpoche

It is very important to note that the level of ‘reality’ accredited to Yidams varies depending on the practitioners level of experience and understanding.

The Vajrayana pantheon serves as a focus for hope and devotion for thousands, few of whom are likely to have the time and resources to engage in the meditational approach that a yogi will take.

The cross-cultural devotion to Avalokiteshvara (spyan ras gzigs), the Buddha of compassion, across the parts of Asia where Vajrayana and Mahayana Buddhism are practiced is testament to this. Avalokiteshvara is found in many forms, including two armed, four armed, eight armed and thousand armed.

In Vajrayana countries this deity is seen as male, whilst in parts of China and Japan it is more commonly depicted as female and is known as Guan Yin or Kannon. Devotees of the Dalai Lamas and Karmapas view them as incarnations of Avalokiteshvara.

Preparation for Sadhana

Before the yogi can engage in the Sadhana fully there are a number of factors that have to be in place.

Firstly, he needs to have a Guru (bla ma) who can initiate and instruct him, and secondly he may have to complete various preliminary practices known as Ngondro (sngon 'gro), although some of the practices of the Ngondro, such as Vajrasattva (rdo rje sems pas) and Guru Yoga (bla ma'i rnal 'byor) are no different from the Yidam deity meditation that shall be discussed in detail later.

Ngondro varies slightly between the different lineages of Tibetan Vajrayana, but generally consists of performing 100,000 prostrations with taking refuge and generating Bodhicitta, 100,000 Vajrasattva 100 syllable mantras, 100,000 Mandala offerings and 100,000 Guru Yoga.

Whilst the teacher is important to varying degrees in most schools of Buddhism, in Vajrayana Buddhism he is a key figure, without whom practice is impossible for the yogi. In Vajrayana the Guru is seen as a Buddha.

Although in their realization they are Buddhas, in their actions they are attuned to how we are. With their skilful means they accept us as disciples, introduce us to the supreme authentic Dharma, open our eyes to what we should do and what we should not do, and unerringly point out the best path to liberation and omniscience.

In truth, they are no different from the Buddha himself; but compared to the Buddha their kindness in caring for us is even greater. Always try, therefore, to follow your teacher in the right way, with the three kinds of faith Patrul Rinpoche

The reason for the centrality of the Guru in Vajrayana lies in the difficult concept of the transference of ‘chinlap’ (byin rlabs), which is varyingly translated as grace, empowering energy, inspiration or blessing.

It is difficult not only due to the lack of a perfect translation, but also because it is something which is difficult to study academically as an outsider to a tradition.

Kalu Rinpoche compares it to electric power in that it flows from the Buddha, through the lineage of transmission to the yogi. Consequentially the Yidam is seen as inseparable from the Guru, in fact the Sadhana liturgical text used for this paper sees the deity addressed as Lama.

Assuming the Guru has this ‘empowering energy’, the yogi has to have certain corresponding qualities for the transference to work. There exists a great deal of writing, both Tibetan and Indian on the requirements of both Tantric Gurus and their disciples, Jamgon Kongtrul devotes several chapters of his encyclopaedic Treasury of Knowledge to exploring these qualities as well as how the yogi should follow his Guru as well as how the process of finding a suitable Guru should be undertaken, similarly Patrul Rinpoche has a whole chapter on the topic in Words of My Perfect Teacher.

Ashvaghosa’s Fifty Stanzas of Guru-Devotion is a more condensed and poetic description, which Jamgon Kongtrul extensively quotes from and comments on. In brief, the qualities required of the Guru are summed up as being honest, compassionate and loving towards all sentient beings, having a tamed mind and being knowledgeable about the tantras, sutras and shastras.

Kongtrul also talks about the different types of Guru in terms of whether or not they are a layperson or ordained to novice level (dge tshul) or have full ordination (dge slong), where he concludes by saying that a fully ordained Guru is best, unless he or she is someone who has reached the first bodhisattva Bhumis as the realisation that goes with this supersedes any issues of which vows they have as ‘support’.

The aspiring yogi must have certain qualities which Jamgon Kongtrul lists as: devotion, ability to understand the ‘profound view’ or pure view (dag snang), confidence or faith in Tantric practice and the ability to keep pure samaya (dam tshig).

It is generally accepted that keeping a pure view of the Guru is essential to the maintenance of samaya, and that samaya is established once a connection is made between a Guru and a yogi.

As Tantric commitments and samaya are seen as extremely serious business, it is important that the Guru and prospective disciple examine each other very closely rather than immediately rushing into a relationship which could be detrimental to both of them. Patrul Rinpoche quotes Padmasambhava:

Not to examine the teacher, is like drinking poison. Not to examine the disciple is like leaping from a precipice.

Once the basis for a proper Guru disciple relationship has been established, the Guru can then empower the yogi to practice.

According to Stephan Beyer there are five types of “transmission of lineage and authority”, ranging from the more fantastical “revelatory” and the hidden treasure (gter ma) tradition of Padmasambhava to the more commonplace “lineage of initiation, textual transmission and instruction”.

When discussing Sadhana in a general sense it is most expedient to focus on the latter, although there are many Sadhana practices that come from the hidden treasure tradition of the Nyingma lineage.

Vajrayana empowerments have three parts: the actual empowerment ritual (dbang), the reading transmission of the liturgical Sadhana text (lung) and the actual meditation instructions (tri) for the deity. The empowerment ritual itself can be more or less elaborate, but always contains the vase empowerment, secret empowerment, knowledge-wisdom empowerment and speech empowerment.

Irrespective of how elaborate the initiation ritual itself is, it can be summed up as giving the aspiring yogi the permission and ability to meditate on himself as the deity in order to understand the union of appearance and emptiness, the permission and ability to meditate on the union of sound and emptiness through receiving and reciting the mantra of the deity and also to meditate on the union of emptiness and compassion through the mind of the deity being given.

In order for the empowerment ritual to be successful, the Guru must be motivated by love and compassion, as well as having some experiential meditational accomplishment of both the development (bskyed rim) and completion (rdzogs rim) stages of the deity of whom the empowerment that is being given.

The aspiring yogi must also trust the specific ritual and the Guru, and the symbolic ritual objects must be in place. Refuge and Bodhisattva vows are also included in all empowerments. After being initiated and receiving instructions the yogi is then ready to start practicing the Sadhana of the particular deity in question.

Structure of a Sadhana.

The ritualised structure of most Sadhana practices is pretty similar, so for the sake of simplicity I will illustrate by primarily focusing only on one relatively common Sadhana, All-Pervading Benefit of Beings,

The Meditation and Recitation of the Great Compassionate One. This is a short Avaloketishvara (spyan ras gzigs) Sadhana by the ‘renaissance man’ figure of Tangtong Gyalpo9 (thang stong rgyal po), which is practiced across Kagyu, Nyingma and Shakya (sa skya) lineages.

It belongs to the Kriya class of Tantra.

Like all Vajrayana rituals the Sadhana starts with taking Refuge and generating Bodhicitta (byang chub kyi sems). Taking Refuge in the Three Jewels, is what makes this meditation specifically Buddhist, whilst the generation of Bodhicitta is what marks it as a Mahayana practice. Vajrayana Buddhism has Mahayana philosophy and ethics as its foundation, the techniques and practices described in the Tantras are what make it different from other the other Mahayana traditions.

Depending on time and the elaborateness of the ritual, after this there may be inserted various other prayers of aspiration such as the Four Immeasurables (tshans pa'i gnas bzi) or various lineage prayers, either to the general lineage of the yogi or the lineage of transmission of the particular practice.

There may also be offering prayers or some sort of Mandala offering. However in this particular Sadhana there is not. During this part of the Sadhana the deity, in this case Avaloketishvara, is visualised as appearing in space in front and above the yogi, thus the deity is supplicated for Refuge as well as being an object of offering.

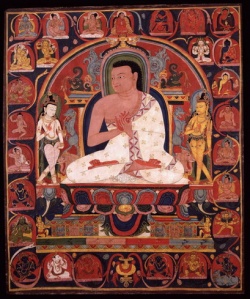

From the HRIH, appears noble and supreme Avalokita. He is brilliant white and radiates the five lights. Handsome and smiling, he looks on with eyes of compassion.

He has four hands: the first are joined in anjali; the lower two hold a crystal mala and a white lotus. Adorned with ornaments of silk and jewels, he wears an upper garment of deerskin. Amitabha ('od dpag med) crowns his head. His two feet are in the vajra posture. His back rests against a stainless moon. He is the embodiment of all objects of refuge Dzogchen Ponlop Rinpoche

The syllable HRIH is the seed syllable of Avalokiteshvara. When meditating, the yogi will visualise radiating lights from this syllable, which is standing on a lotus and moon.

These lights are seen as going in two directions: Firstly the lights go ‘down’ to relieve the suffering of sentient beings in samsara, they do this by taking the suffering and bringing it back to the HRIH. Then the lights go ‘up’ to all the Buddhas and Bodhisattvas carrying offerings, the lights return then return carrying the blessing of these deities which transforms the HRIH into Avalokiteshvara.

The physical features relate to various Buddhist teachings or have other symbolic meaning, in some cases multiple meanings. The four hands correspond to the Four Immeasurables; the joined hands are holding a jewel which is representative of Bodhicitta.

The mala represents the drawing of beings towards liberation, whilst the white lotus is symbolic of purity and working in the world without being tainted by it. Sitting in the vajra posture symbolises the union of compassion and emptiness, the deer skin represents the legendary kindness of the deer. Amitabha is visualised on top of Avalokiteshvara as he is his teacher in the traditional mythology of Avaloketishvara.

After this the liturgy contains a short supplication of verbal prostration to Avalokiteshvara. In the fasting ritual of the thousand armed Avalokiteshvara (smyung gnas), physical prostrations are performed whilst chanting this particular supplication prayer.

Next comes the seven branched prayer, various versions of which are found in most Sadhanas, it is also found in all Mahayana Buddhist schools. In this Sadhana text the words are given, but this is not always the case.

The act of homage functions to reduce pride and foster a sense of devotion, whilst offering is intended to generate merit (bsod nams), whilst also being an expression of the Bodhisattva perfection16 of generosity (sbyin pa) and a way of reducing greedy tendencies.

Confession, if done sincerely and in conjunction with Four Powers, is believed to reduce the effects of negative karma, or even purify it completely.

Rejoicing in the virtues of others is a way of generating merit, habituating oneself to valuing virtue, effectively functioning as mind training.

Requesting the teachings generates merit and also serves to express and develop further appreciation for the teachings. Requesting the Buddhas to not enter Nirvana is similar to requesting the teachings and dedicating the merit makes the whole practice a Mahayana practice and aids the development of Bodhicitta.

Whilst the above order is generally how the seven branch prayer is performed, the 9th Gyalwa Karmapa Wangchuk Dorje (dbang phyug rdo rje) states that Refuge is occasionally added between making offerings and confession.

After the seven branched prayer there is a supplicatory prayer called, “The supplication of calling with longing”, where the relationship between negative emotions and their corresponding samsaric realm is laid out.

This reminds the yogi to be mindful of these emotions, develops renunciation by contemplating the suffering of samsaric existence and develops compassion as each verse ends with a supplication that beings from the realm mentioned be born in the presence of Avalokiteshvara, which can be taken literally or as an aspiration that all beings develop the non-dual compassion embodied in Avaloketishvara.

This part of the liturgy concludes with aspirations to carry out the activities of Avaloketishvara, as up until now the visualisation has been of the deity as something external ‘in front’ of the yogi. This changes during what could be considered the main part of the visualisation.

The main visualisation is done according to the description in the first part of the liturgy, however the radical difference is that the yogi is now identifying himself with the deity.

The initial stage of the visualisation, with the syllable HRIH transforming is done exactly as before this visualisation is known as the ‘pledge being’ (dam tshig pa), this is a complicated concept, but basically means it’s created purely by the yogi, who after receiving initiation is a holder of a pledge, or samaya (dam tshig), with the deity in question.

The yogi then visualises lights emanating from a HRIH in his heart, which summons the wisdom deity (ye she pa) who effectively consecrates the initial visualisation.

The visualisation is now seen as more ‘alive’, and at this point the yogi will remain in this state whilst reciting the mantra of the deity, which in this case is the six syllables OM MA NI PAD ME HUNG18.

This mantra is then visualised as circling the white HRIH inside the yogi visualised in the form of the deity.

Each syllable emits lights which pacify a corresponding negative mental state and realm of existence.

The 15th Gyalwa Karmapa, Khakhyab Dorje (mkha' khyab rdo rje), lists them in the following way: OM is white, and purifies pride and karma associated with the gods realm. MA is green, and purifies jealousy and karma associated with jealousy.

NI is yellow, and is associated with the human realm and purifying desire. PAD is blue, and purifies the karma associated with ignorance and the animal realms. ME is red, and purifies the negative emotion of greed which is associated with the hungry ghosts (yi dags), whilst HUNG is black, and associated with purifying aggression and hatred in the hell realms.

All beins are transformed into the deity and all realms are transformed into Sukghavati (bde ba can), the land of bliss.

All of this is a rather complicated process of multitasking and simplified versions are encouraged until the yogi is able to carry out the whole process.

This part of the meditation is what is known as the creation stage (bskyed rim).

As mentioned this is quite an all encompassing process, however it is essential that the yogi keeps a view of emptiness during the process, as to avoid simply replacing the samsaric ignorance driven reality with another, perhaps seemingly more pleasant one. According to Padmasambhava:

Do not regard the Yidam deity as a form body; it is a Dharmakaya.

The meditation on this form body as manifesting from Dharmakaya and appearing with colour, attributes, ornaments, attire, and major and minor marks should be practiced as being visible while devoid of a self-nature.

It is just like the reflection of the moon in water.

When you attain mental stability by practicing like this, you will have a vision of the deity, receive teachings, and so forth. If you cling to that you will go astray and be caught by Mara. Do not become fascinated or overjoyed by such visions since they are only the manifestations of your mind.

The yogi will do this part of the practice for a certain period of time, which is not specified, although some Sadhanas specify a certain number of mantra recitations for each session.

After this the yogi will begin to dissolve the visualisation as part of beginning the completion stage (rdzogs rim).

The process of dissolving the deity, much like the creation stage, can be done in a number of ways, but they are either gradual or instant. If it is done gradually, the deity is visualised as melting into the mantra, which melts into the seed syllable, in this case a HRIH, which is then dissolved in stages, until it dissolves into emptiness.

Once the visualisation is dissolved, the yogi rests in the natural state into which the Yidam deity has dissolved.

According to Vajrayana, this natural state of mind is Mahamudra (phyag rgya chen po) or Dzogchen (rdzogs pa chen po), and is no different from Buddhahood itself. This is effectively a ‘formless’ meditation as there is nothing to cling to and is simply experiencing reality as it is, free from dualistic fixation.

Free from intellectual speculation, it is Mahamudra. F

ree from extremes, it is the great middle way. Being the totality of everything, it is also called the great perfection (Dzogchen). May I gain conviction that to know this one thing is to understand all. From Rangjung Dorje's "Aspiration of Mahamudra"

Becoming accustomed to, or familiar with this state, is really what Mahamudra and Dzogchen meditation is and as such Yidam deity meditation is an effective way of practicing. How long the yogi rests in this state will depend on his level of experience, although it is probably not very long for most practitioners as any conceptualisation. According to Jamgon Kongtrul this part of the practice lasts while there are no “discursive pursuits of altering, accepting or rejecting”.

For the reasons described above there is no liturgical commentary in the practice text, apart from “rest evenly in your own nature”. The secondary reason for this is that Mahamudra and Dzogchen are not general and open teachings, but are traditionally taught from Guru to disciple only after a proper relationship has been established and trust has been established.

As such, the next part of the text concerns keeping pure perception (dag snang) and the pride of the deity, which was developed during the creation phase.

These are basically keeping a view of the world as the pure land of the deity, oneself and all beings are the deity and all sound are the mantra. This is not a visualisation, rather an attitude or ‘view’, continuing what has been experienced and learnt during meditation:

During meditation you rest in the inconcrete essence of Dharmata, cognizant but without conceptual thinking. During post-meditation, you realise everything to be empty, without self-nature. Free from attachment to or fascination for the experience of emptiness, you will naturally progress beyond meditation and post-meditation and be free from holding a conceptual focus or conceiving of attributes, just as clouds and mist spontaneously clear in the vast expanse of the sky MahaGuru Padmasambhava

The liturgy then goes into the sealing of the practice with the dedication of merit, which should be done with a continuing understanding of emptiness. After this comes an aspiration prayer for oneself and all others to achieve rebirth in Sukhavati as well as other aspiration prayers for the development and spread of Bodhicitta.

Benefits of this practice

The various commentaries on this practice go into some degree of detail as to the benefits of this practice, and on various other aspects of it. The mantra of Avaloketishvara is ubiquitous anywhere Tibetan Vajrayana is practiced, recited by everyone, painted on rocks, prayer flags and over doors.

Bokar Rinpoche points out that Tibetans recite the mantra without having received the initiation and without doing the visualisation, but purely out of “faith and devotion acquired since infancy”. In his commentary, the 15th Gyalwa Karmapa, Khakhyab Dorje, quotes from the "Root Tantra of the Lotus Net":

The Mandala of body that accomplishes meditating on all Buddhas combined is the body of the protector. Through meditating on or even recalling it, the actions of immediate retribution and all obscurations are purified.

His teacher, Jamgon Kongtrul, finishes his commentary on the practice of Avaloketishvara by saying that the benefits of it “cannot be properly conveyed using words” and that it benefits “all those whom it comes into contact (with)”.

As if to highlight the importance of impartial compassion, he encourages the sound of the mantra to be shared with animals “from ants upward” and ends by an exhortation for everyone to practice.

Functions of the meditation.

Buddhist meditation can be classified as either calming, or Shamatha (zhi gnas) meditation, which lays the foundations for insight or Vipassana (lhag mthong) meditation.

Whilst these can, and are practiced separately in the Tibetan tradition, they are combined within the practice of Yidam deity meditation.

During the development stage the details of the appearance of the deity and the mantra serve as a focus for the mind which, with sufficient practice, leads to a gradual calming of the mind. Insight is developed by keeping the visualisation light and non solid as mentioned previously.

The union of calm and insight is Mahamudra:

The deity is, therefore, appearance-emptiness. But it is not, on the one hand, appearance and on the other hand, emptiness, sometimes appearance or sometimes emptiness.

Being an appearance it does not lose its emptiness; being empty it does not lose its appearance. It is the union of appearance and emptiness, not with the meaning of two things placed side by side, but with the meaning of the two things forming the same indissociable reality.

To dwell without distraction in this state of union is the simultaneity of mental calm and superior vision. This is also called Mahamudra and more precisely in this case, the Mahamudra of the deity’s body. Bokar Rinpoche

Earlier it was mentioned how the yogi in post-meditation should keep the view and pride of the deity. This in itself will serve as an exercise in mindfulness as well as further developing devotion and compassion.

By doing this it is possible to use “all the circumstances of existence” as part of the yogi’s spiritual practice.

When walking the yogi will visualise the deity over his right shoulder so as to transform the walk into a devotional circumambulation, when sitting the deity is visualised seated above his head.

When the yogi eats he will imagine the food as an offering to the deity, which he will visualise in his throat, whilst at the same time seeing the food itself as amrita (bdud rtsi).

When going to sleep the deity is visualised at the heart emitting light. There are variations on these practices as well as lots of others serving similar functions, the main point is that the “view” is maintained. According to the 9th Karmapa Wangchuk Dorje, appearances are like a “mirage” in post-meditation.

Technical points of meditation.

As we have seen, Yidam deity meditation can be extremely complex, and so far this is without the inclusion of additional factors that may be included in particular Sadhana practices, such as playing ritual music, making physical offerings in the forms of torma (gtor ma) offerings. As such there are a few points which are crucially important to note.

Meditation is often portrayed as a way to relax, and whilst relaxation and calming are effects of successful meditation, it is also important to relax before meditating.

Rather than worrying about whether or not the whole deity is visualised in glorious three dimensional form, the aspiring yogi should relax and take an approach of focussing on specific parts of the deity in turn, rather than trying to see everything at the same time.

Bokar Rinpoche advices against approaching the process in a “rigid and too structured way”, suggesting instead that one begins with simply adopting the thought of being the deity, before moving on to specific parts of the visualisation once one feels more confident. This way, the whole process is gradually built up in a relaxed and natural way.

When a little child is seated in the middle of many toys, he does not consider playing with them all at once. He takes one toy and plays with it for awhile, then when he has had enough, he takes another that he in turn puts away to play with a third, and so on. He has many toys but he does not worry about being able to play with them at the same time. He knows they are there, that one toy is enough and when he is bored with it, he can take another. Bokar Rinpoche

Whilst taking a gentle relaxed approach, it is also important that the yogi does not let the mind wander completely, so a typically Buddhist “middle way” approach is generally recommended. Kagyu Lamas often talk of "little and often" when it comes to formal sitting, not just in relation to yidam practice, so it might be a good approach.

Conclusion.

We have seen that Yidam deity meditation is a ritual practice which covers many areas of the yogis training. Yidam meditation allows the yogi to engage in the ‘two accumulations” (tshogs gnyis), the accumulation of conceptual merit by offering the seven branch prayer, and engaging in the Bodhisattva perfections, whilst accumulating non-conceptual wisdom by keeping a view of emptiness both when engaged in the actual visualisation and in the post-meditation. Both relative, and ultimate, Bodhicitta are also developed.

Relative Bodhicitta, in the form of dualistic compassion is developed through the recitation of the Bodhicitta prayers, the visualisation of lights liberating the suffering of others and by the dedication of merit, whilst ultimate Bodhicitta is developed by seeing the Yidam deity as the union of appearance and emptiness, as ultimate Bodhicitta is emptiness or the direct experience and understanding of it. The practice simultaneously develops calm and insight,

the union of which is considered to be the fruition of Mahamudra or Dzogchen practice. From the Mahamudra point of view, nothing has then been achieved in terms of creating something new, rather what is naturally there has been realised directly and spontaneously as it is, rather than through conventional dualistic mind.

The present mind having been released freely into the state of naturalness, the unmodified spontaneous perfection of whatever arises, there is no attachment towards external and internal phenomena. (

In the present mind,) as there are not thoughts of rejecting or accepting, the state of non-duality of the mind remains ceaselessly.

As there are no gross thoughts, the wildly roaming mind has been liberated from the thoughts of the desire (realm). As the projecting thoughts have arisen in naturalness, the mind has transcended all diversion to the form and formless realms.

Having no apprehension as “this”, the tranquillity has been accomplished spontaneously. As the naturalness (so ma) (of the mind) has arisen spontaneously, the insight has been accomplished spontaneously. As there is no separate and projecting and dwelling, their union has been accomplished spontaneously.

As it has been liberated in the instantaneous state itself (or instantaneously in its own state), the wisdom has been accomplished spontaneously.

As there is no dwelling, the absorption has been accomplished. As there is no apprehension of liberation-upon-arising (of intrinsic awareness), the primordial wisdom has been accomplished spontaneously. As all the faults are present through the aspect of apprehension, they are liberated in freedom from apprehension and hindrances.

As all the virtues arise in the awareness wisdom, they are progressing. It is the mind perfected in its own naturalness, and it is the supreme accomplishment of the Great Seal (Mahamudra), in this very lifetime.

Longchenpa

To conclude, the yogi, through the practice of the Yidam deity meditation, simply comes to see himself, and the world as they are. According to Vajrayana Buddhism, ultimately everything is pure, but through dualistic thinking, rooted in a belief in a separate and inherently existent self, things appear and are experienced as impure and painful, as such the Yidam meditation becomes the yogis corrective glasses.

This is a rehash of an acadmic essay I wrote, minus the footnotes and bibliogrpahy. Should any merit have been generated, may all beings benefit from it.

Posted by Karma Phuntsok