Turning the Body into Food - The Secret Treasure of the Dakini.

Extract from Chapter 15 by James Low of The Yogins Of Ladakh: A Pilgrimage Among The Hermits Of The Buddhist Himalayas. By John Crook and James Low (Motilal Banarsidass, Delhi, 1997) IBSN 81-208-1462-2. Republished 2007.

One of the Chod texts that I used in my practice in Ladakh was written by Nuden Dorje Dropen Lingpa Drolo Tsal in the latter part of the nineteenth century in East Tibet.

It is entitled "The Brief Practice for Turning the Body into Food taken from the Secret Treasure of the Dakini."

As the colophon at the end of the book tells us, he wrote it at the request of one of his disciples while he was staying at Tsone which was the retreat centre linked to his own monastery of Khardong.

Only that part of the text which is specifically the Chod practice is considered here. The complete text also includes all the elements present in a tantric preliminary practice.

Doing the chod practice

In the cemetery, Chod is performed six times a day; twice in the morning, once at noon and three times in the evening and night. I used this Chod twice a day, Jigmed Lingpa's practice text Khandro Gadjang twice and Gonpo Wangyal's practice text Tharpa Go Je twice. The first part of the text is a reminder of how rare is the opportunity to practise the Dharma. This is followed by taking refuge in the usual tantric fashion with a particular focus on Machig Labdron, and a request for blessing. After this an offering is made of all that is deemed precious in order to lessen attachments and increase merit.

The main practice follows, in which the yogin visualises his awareness leaving his body through the top of the skull and transforming into a wrathful goddess who then chops up the body and piles it into the top of the skull. This then becomes a great offering bowl filling the universe. All the beings of samsara and nirvana, ranked according to their spiritual realisation, are invited to feast on the mangled remains of the body which transform into whatever the guests desire.

Text

"Hri. This arrangement of the outer, inner and secret mandalas is offered to the unfailing Three Jewels. Using my intellect to remove my belief in a truly existing self, may my mind arise free from desire. May I quickly realise my mind to be unborn."

"Phat! My awareness leaves my body via the central channel. It becomes the fierce dakini who then cuts off my corpse's cranium with her curved knife. Set up on a tripod of skulls,

it pervades the entire Universe and contains the undefiled desirable qualities of the various constituents of the body."

"Phat! I give this to all those to whom I have owed services in my lives throughout beginningless time, and who have now become the sickness-causing demons and -- obstructers. All debts and help unrepaid are thus paid off. I offer this to the guests who arrive suddenly for the remainders, those of the intermediate place, the weak and those of little power."

"Phat! With this great wealth displaying whatever splendid qualities the guests desire - all beings must gain Buddhahood. With all the hosts of thoughts of samsara and nirvana being liberated in their own place, the original nature must be fully realised in the experience of direct understanding." "Phat! Phat! Phat!"

When the guests have finished, the three loud cries of PHAT are made cutting through all thoughts grasping at embodied identity. The yogin then abides in the resultant open awareness for as long as possible sounding off further PHATs to cut through the seductive web of reification.

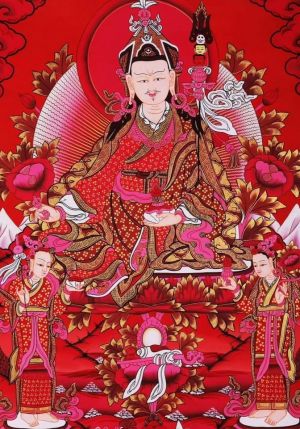

Brief practices to accumulate merit and purify error follow and then a long meditation on one's guru in the form of Machig Labdron. This involves an elaborate visualisation of the deities of her mandala and the recitation of the lineage prayer linking the original inspiration of the Buddha down through all the teachers to one's own lama. After praying as follows the practitioner finally receives the initiation of the guru's enlightened being and then merges in emptiness.

"Please bless us so that our difficulties can be used as the path.

Please bless us with the power of experiencing the equal taste of the dual ideas of happiness and sadness and so forth

Please bless us that unhelpful bad conditions may become our helpers.

Please bless us with the power to benefit the local gods and demons, and all beings.

Please bless us with the completion of ego-cutting by severing the root of confusing dualistic thoughts

Please bless us that in this very life we may gain the supreme real attainment of radiant clarity."

The body, focus of our attachment, sensual pleasure and fear of death, is transformed into food to benefit others. Attachment and self-centredness are replaced by a profound sacrifice, ultimate altruism. This gift of oneself for the benefit of others also, perhaps

paradoxically, frees the practitioner from the illusion of false identification. The meditation provides a practical experience of the mystical commonplace that one finds oneself by losing oneself.

Commentary

The practice is a ritual enactment which uses identification with the symbolic to shift experience in the perceptual field. Faith is a very powerful and important driving force here for it both opens the practitioner's heart, making him softer, more fluid and able to let go and change, and mobilises the will through a longing aspiration which permits the reframing of ordinary obstacles into ornaments on the spiritual path.

The way of engagement, of participation, that is recommended is one of openness and generosity. In particular we are enjoined to think first of those we might wish to deny and exclude, our demons, those who make trouble for us. By this gesture, demons and enemies are included rather than excluded, the 'shadow' is owned and given a place in the developing field of wisdom and compassion. Refuge is open to all and the price of entry is not adherence to a dogma but rather an attitude of openness to change grounded in a phenomenological acknowledgement of one’s present situation; “I am in pain I am lost I need help.” And help is there for the asking, gurus, Buddhas, deities are forces in play, not separate ‘others'.

Phat

The practice offers a powerful means of shifting habitual patterns of identification and reflex response. The cry "Phat’' cuts through the chain of thought construction that holds the ordinary world in place. There is a gap, a moment of possibility - like using the clutch to disengage gear before changing it. Awareness is relocated around the image of the fierce dakini who then destroys the line of retreat by cutting up the body one has just left, and transforming it into an offering suitable for the gurus and higher deities. The lines have been sung to the accompaniment of the large drum (damaru) and handbell. With ‘Phat’ the meditator cuts off thought, letting go of reliance on ‘good’ images and fear of ‘bad’ images. This is the heart of the

meditation, the gap in the practice which opens up and widens the gap between thoughts; cutting off thought, cutting out distraction, cutting through to the experience of integrated presence. By cutting out frightening images as they arise, the meditator uses the power of the practice to expose the essential emptiness of the danger. When this experience is deeply felt it gives rise to the realisation that there is no danger. The yogin becomes fearless through an ability to see the essential emptiness in the moment of experiential arising.

Identifications. Being is always becoming

During the course of the practice the meditator takes on a series of identifications, becoming a wrathful goddess, a calm purifying god, the fearless yogi. In longer texts there may be over a hundred shifts of personal identification. In this manner the selfreferencing function of the practitioner is put into question, for the usual identification

with the subjective sense of self, the felt sense of 'I', is clearly undermined by the experience of being 'another'.

The deity is not a play acting role or alternative self. The deity is the presence of the radiance of the symbolic which permeates the manifestation that, in our dullness, we take to be the real world of ordinary reality, things as they are. To identify with the deity is to enter another mode of the same dance. It is not to become somebody else but to realise that one never becomes anybody per se. Being is always becoming, always in play, in display, in the presence of the dance. And the identification with the deity permits a moment of recognition; there is nowhere to leave and nowhere to arrive. Nothing, nothing doing, nothing doing everything. Nothing exists, and it's fine.

Everything that appears, good or bad, pleasant or unpleasant, is located within the presence of the Buddha.44 Then with nothing to defend and nothing to gain the yogin is free to experience things as they are, in the simplicity of their presentation. Machig Labdron, once human now divine, or always divine and sometimes human, is an ideal representation for this process.

The Guru offers the reliance of non-reliance

The practice ends with an intensification of devotion, calling on the guru never to forget us. Out in the cemetery in the dark night and the howling wind, who will help us? In tragedy and terror, who can help us? Those who distract us with kind words and helpful concepts may be doing their best - and it may appear to help - but what such well meant help sets in play is only another fantasy of reliance. The guru, by contrast, offers only the reliance of non-reliance, of a certainty that opens up the splendours of the sky, the profound safety net of emptiness that catches us as we fall towards the living death of reification.

"In accordance with what I have prayed for, may the natural condition be realised just as it is with the symbol of rainbow light manifest, aware, clear and empty. -- May we all realise this pure spontaneous original display."

Once the transmission of this awareness has been received through the four initiations, the form of the guru dissolves into light and flows into us so that we also dissolve in light that gently fades like a rainbow, leaving us safe in the open expanse of presence. Within this our lives continue, getting up, making a cup of tea, nothing special.