Establishment of the Buddhist Monastic Code

By Khai Thien

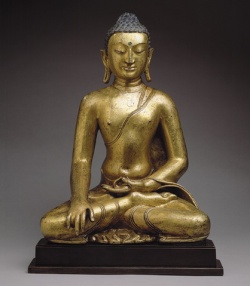

Vinaya texts, the Buddhist moral code from the Tipitaka (Sutta, Vinaya, and Abhidhamma), are always considered the most important to the system of any organization or group of sangha (monks and nuns). Without Vinaya established as the Buddhist disciplinary rules—the foundation for the life of Buddha-dharma—the house-structure of sangha and even Buddhism cannot exist. In order to trace the history of the establishment of the Buddhist monastic code as well as Buddhist training rules in general, this paper will explore the status of the sangha order in the Buddha’s lifetime, including the early years of the Buddha, the early Buddhist ordination with three refuges, the establishment of Pratimoksa, the contents of Pratimoksa, the Uposadha day, and the first Council of Vinaya.

I. The Early Years of the Buddha’s Career

According to Pali chronology, Buddhist moral codes for both monastic and lay people were established gradually according to various conditions and situations throughout the Buddha’s life. Upon the Buddha’s achievement of enlightenment, no sangha (monastic community) existed. Thus, the Buddha’s first monastic disciples were the five brothers of Kondanna, who took refuge in the Buddha and his dharma after listening to his first sermon, theFour Noble Truths—Dhammacakkappavattana (turning the wheel of dharma)—at Deer Park, near Benares. This special event marked the first time in human history that Buddhism contained the Buddha, dharma, and sangha—otherwise known as the Triple Jewels. The next twenty years of the sangha developed primarily according to dharma, the Buddha’s teachings. As Pali canons tell us, at that time, the community of bhikkhunis (nuns) had not yet been founded within the community of sangha; only bhikkhus (male) existed, and they had all achieved high personal attainments with great insight and direct knowledge of dharma. They were the noble ones and Arahants “who had succeeded in subduing many or all of the defilements of their minds. They knew his teachings well and behaved accordingly.”[1] As such, there was no need to formulate disciplinary rules for those who lived in the sangha directly under the instruction of the Buddha. The texts tell us that, Thera Sariputta once requested the Buddha to formulate the monastic rules for the sangha members, but the Buddha replied, “Wait, Sariputta. The Tathagata will know the right time for that. The Teacher does not make known, Sariputta, the course of training for disciplines or appoint the Patimokkha until some conditions causing the pollutions (asava) appear here in the Sangha.”[2] The Buddha himself confirmed the status of his monastic system in the early period by saying that “In former times, you know, bhikkhus were fewer in number but those possessed of supernormal powers.”[3] Ultimately, during this perfect period of the sangha, Buddha and dharma served as the two refuges for the entire community of monastic monks.

II. The Early Buddhist Ordination

Early in the Buddha’s career, the procedure to ordain a person who wanted to become a monk was quite simple. According to the Vinaya texts, “those who were convinced and/or asked to join with him, He allowed them to be bhikkhu by saying that, ‘Ehi bhikkhu, svakkhato dhammo caro brahmacariyam samma dukkhassa antakiriyaya’ (Come bhikkhu, well-expounded is the Dhamma, live the brahmacariya for the complete ending of dukkha).”[4] This “procedure,” called Ehi-bhikkhu upasampada (acceptance by saying “Come bhikkhu!”) became the official words of ordination used for those who wanted to join the sangha during the Buddha’s early years.

The Mahāvagga, in Vinaya Pitaka, further informs us that the first Buddhist mission was sent to various places to propagate the dharma. The mission included sixty-one monks from the sangha (the first sixty-one bhikkhus), who went forth to preach the dharma to the world following the encouragement of the Buddha:

Freed am I, O Bhikkhus, from all bonds, whether divine or human. You, too, O Bhikkhus, are freed from all bonds, whether divine or human. Go forth, O Bhikkhus, for the good of the many, for the happiness of the many, out of compassion for the world, for the good, benefit, and happiness of gods and men. Let not two go by one way: Preach, O Bhikkhus, the Dhamma, excellent in the beginning, excellent in the middle, excellent in the end, both in the spirit and in the letter. Proclaim the Holy Life, altogether perfect and pure. There are beings with little dust in their eyes, who, not hearing the Dhamma, will fall away. There will be those who understand the Dhamma.[5]

In carrying out this mission, the missionary monks faced new difficulties, particularly when new aspirants wanted to become bhikkhu officially as well as join the sangha. At that time, the missionary monks had to present newcomers to the Buddha for acceptance. Realizing this difficulty, the Buddha allowed the savakas (bhikkhus) themselves to ordain those who wanted to join the sangha without presenting them to the Buddha. However, the procedure changed in such situations. Whenever a person sincerely wanted to become a Buddhist or adopt the monastic life, he had to say the solemn words for taking refuge in the Triple Jewels three times:

Buddham Saranam Gacchami – I take refuge in the Buddha.

Dhammam Saranam Gacchami – I take refuge in the dharma.

Sangham Saranam Gacchami – I take refuge in the sangha.

After saying these verses three times in front of a preceptor, he would officially become a Buddhist. Although the procedure initially applied to new monastic persons called Pabbajja (novice monk), it later applied to lay persons as well. This method of acceptance is called Tisarnagamamupasamda (acceptance by taking refuge in the Triple Jewels).

Soon the sangha’s members increased remarkably. Consequently, the Buddha wanted to establish a firm foundation for the sangha in which each group of bhikkhus was required to have at least four members. This resulted in a new procedure called the Nati-catutthakamma-upasampada (bhikkhu assembly). From this point, the approval of becoming a bhikkhu required being conducted in front of four monks in a limited area, called sima. This ordination remains today, leading to the three procedures of the Buddhist monastic ordination: Ehi-bhikkhu upasampada, Tisarnagamamupasamda, and Nati-catutthakamma-upasampada. Two kinds of ordination are mentioned in the time of the Buddha: the Pabbajja used for monks under twenty years old (samanera) and the Upasampada used for bhikkhu, a man who takes ordination after he has turned twenty. When a samanera receives ordination, the Tisarnagamamupasamda applies.

III. The Establishment of Pratimoksa

According to Caturvarga-Vinaya (Four Divisions of Vinaya) as recorded in Vinaya Tipitaka, the Buddha did not immediately set up a comprehensive moral code for either the monastic or laity; rather, he formulated disciplinary rules one at a time according to specific occasions and/or in response to the nature of each matter. It is possible to say that each rule of Vinaya had its own story, as evidenced in both the Mahāvagga and Cullavagga.

As discusses, the sangha developed quickly; consequently, some entered the sangha with their karmic habits, weaknesses, and even felonies, diluting the quality of the entire family of sangha compared to its absolutely pure realm initially. To address this impurity, Thera Mahakassapa once said to the Buddha, “What are the conditions now Lord, what is the cause that formerly there were both fewer precepts and more bhikkhus were established in profound knowledge (arahantship). What are the conditions and cause that now there are more precepts and fewer bhikkhus established in profound knowledge?” In addition, some bhikkhus committed serious mistakes that had never happened in sangha. For instance, the bhikkhus who lived in Sarali forest and practiced asubhasmrti visualization gradually became disgusted with the existence of their own impure bodies and ultimately committed suicide in various ways. Some killed themselves, but others requested the Brahmin who lived nearby to kill them with a knife. When the Buddha heard of this, he formulated the third Parajika (prohibiting the killing of a human being, be it oneself or another). Similarly, the first Parajika (prohibiting sex with a human, non-human, or anything down to an animal) arose from the story of bhikkhu Sudinna, who had sexual intercourse with his ex-wife three times in the forest. In response to this matter, the Buddha laid down the training rule prohibiting the monastic order from having sex. It is crucial to note that, when the Buddha rebuked Ven. Sudinna, he said, “Foolish man, you are the first doer of many wrong things.”[6] Such words obviously indicated that the Buddha believed such serious offenses would only increase as time passed. After this serious rebuke to Ven. Sudinna’s mistake, the Buddha proclaimed:

In that case, bhikkhus, I will formulate a training rule for the bhikkhus with ten aims in mind: the excellence of the Community, the peace of the Community, the curbing of the shameless, the comfort of well-behaved bhikkhus, the restraint of effluents related to the present life, the prevention of effluents related to the next life, the arousing of faith in the faithless, the increase of the faithful, the establishment of the true Dhamma, and the fostering of discipline.[7]

Following such serious problems among the bhikkhus, the basic rules of monastic code was established. In such a way, the Buddha formulated more than 200 major and minor rules, establishing the Patimokkha, which was recited twice a month in each community of bhikkhus. Generally speaking, the modern monastic code emerged in response to various matters of reality, developing over time until the day the Buddha left the Saha world and entered the Great Nirvana.

IV. Contents of the Pratimoksa

According to Dr. W. Pachow, “Pratimoksa is one of the oldest text in Buddhist canon and the oldest text also in Vinaya-Pitaka…Primarily, it is a collection of liturgical formularities governing the conduct of bhikkhus and bhikkhunis.”[8] Pachow’s research provides several important definitions of Pratimoksa:[9]

Patimokkha ti adim etam mukham etam pamukha etam kusalanan dhammanam tena vuccati patimokkhan ti patimokkham (It is the beginning, it is the face (mukham), it is the principle (pamukham) of good qualities; therefore, it is called Patimokkham).

Yo tam patirakkhati tam mokkheti moceti apayikadidukkhehi tasma patimokkha ti vuccati (Whosoever observes [the rules of Patimokkha), him it releases, delivers from sufferings such as of the inferior states, and so it is called Patimokkha).—from an old Tika quoted by Subhuti.

Patimokkha ti atimokkha patippamokkham atisettham atiuttanam (The Patimokkha is that which is the highest, the extraordinary high, the very best and very highest).

This discussion will first examine the meaning and contents of Pratimoksa (Pali: Patimokkha) as well as how it has been defined in Vinaya texts, particularly in Pali canon.

The content and number of training rules in Pratimoksa are particularly significant in Buddhist chronology according to the Pali canons and other sources from various schools. According to Pachow, the Milindapanha (Nikaya) and Agama (Chinese translation) provide the exact numbers of Pratimoksa; the Pali canon gives 150 rules whereas other sutras in Agama (such as Samyktagama sutras, cf. A. III.87 Sadhika; A. III. 85-86 Sekha; and, A. III. 83 Vajjputta) give 205 rules. However, both the numbers and documents provide an important connection by stressing that the rules have been recited every half month during Uposatha days. Another source, the Pali Text Society’s translation, noted precisely 150 rules; the 75 Sekhiyas and 2 Aniyata were subsequently, creating 227 total rules for bhikkhus’ training.[10] The basic training rules for bhikkhus and bhikkhunis, however, are summarized as we see today in Pratimoksa: 227 rules for bhikkhus and 311 for bhikkhunis. The Patimoksa rules are grouped as follows:

1. Parajika—rules entailing expulsion from the sangha (defeat) (4 for bhikkhus, 8 for bhikkhunis)

2. Sanghadisesai—rules entailing an initial and subsequent meeting of the sangha (13 and 17, respectively)

3. Aniyata—(indefinite) rules (2 and 0, respectively)

4. Nissaggiya pacittiya—rules entailing forfeiture and confession (30 each)

5. Pacittiya—rules entailing confession (92 and 166, respectively)

6. Patidesaniya—rules entailing acknowledgement (4 and 8, respectively)

7. Sekhiya—rules of training (75 each)

8. Adhikarana samatha—rules for settling disputes (7 each)

It is crucial to note that the rules of Patimoksa are divided into two parts: the major and the minor. Although the Buddha enabled the sangha to change and/or remove the minor rules over the course of time, both major and minor rules remain respectfully protected and unchanged, except among a few new schools of Buddhism in the current era. In almost all schools, the major rules (such as the four Parajika, the thirteen Samghavasesa, and the two Aniyata) remain totally the same. Pachow completed a very helpful comparative study of the Vinaya rules, discovering no difference among major rules in Sarvastivadin, Vinayanidava Sutra, Sarvastivada Vinaya, Sarvastivada Vinaya-vibhasa, Mulasarvastivadin, Tibetan, Mahavyutpatti, Dharmagupta, Mahisasaka, Kasyapiya, etc.[11]

V. The Patimoksa and the Uposatha

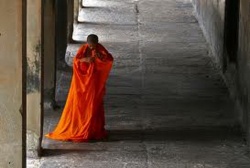

Uposatha is the special day for sangha members, both male and female, to come to together to recite the Patimoksa rules. It is said that Uposatha falls on the eighth and fourteenth (or fifteenth) of every half month. The Buddha allowed monks and nuns to follow this sangha meeting after accepting a suggestion from King Bimbisara at Magadha that groups of monks and nuns should come together on such days to improve their practice.

The custom of Uposatha existed long before the time of the Buddha as the special time when Vedic priests offered their sacrifices. However, the Buddha took this holy day for a new purpose. As described in Mahāvagga[12], the members of sangha initially gathered together in the same place to sit down and meditate in silence. Gradually, their formal meetings became a silent assembly of the sangha. King Ajatasattu once approached 1,250 bhikkhus headed by Lord Buddha and stated, “No sound at all, not a sneeze or cough…would that my son Udayibhadda might enjoy such calm as this assembly has.”[13] This peaceful way of the Uposatha, however, could not benefit many other householders. Some persons complained such silence to be that of “dumb pigs.” Consequently, the Buddha allowed bhikkhus to give dharma talks during such opportunities on Uposatha days.

The next phase of the Uposatha is said to have developed when the Buddha decided to allow bhikkhus to recite the Pratimoksa rules on the Uposatha days after a thought arose in his mind: “What now if I were to allow those rules of training, laid down by me for bhikkhus, (to form) a recital of Patimoksa for them? It would be an act of observance (uposathakamma) for them”. The tradition of reciting Patimoksa was started by the Buddha’s statement “I allow you, O bhikkhus, to recite the Patimoksa.” Thus, during this period in the Buddha’s life, certain training rules had been set out as the official Patimoksa.

Furthermore, the Cullavagga (IX) indicates that the Buddha himself joined the sangha to recite the Ovada Patimoksa. It is extremely important to note that the purity of the sangha became a particularly essential element in performing the Uposatha ceremony. During one occasion when the Buddha was staying at Savatthi in the Eastern Vihara with bhikkhus on the Uposatha day, Ven. Ananda three times requested that the Buddha recite the Ovada Patimoksa. The Buddha replied only after the third request: “The assembly, Ananda, is not entirely pure.” Later, the Buddha said, “Nor, O bhikkhus, should the Patimokkha be heard by one who has an offence.” On another occasion, the Buddha refused to recite the Ovada Patimoksa because the assembly was not entirely pure. Some bhikkhus tried to hide their offenses, but the Buddha had the power to read their minds. Therefore, the Buddha decided to hand over the task of Patimoksa recital to the sangha: “Now, O bhikkhus, henceforth I shall not carry out the Uposatha, nor shall I recite the Patimokkha; you should recite the Patimokkha. It is impossible, O bhikkhus, and it cannot come about that the Tathagata should carry out the Uposatha or recite the Patimokkha in an assembly not entirely pure.”[14] In such ways, the tradition of the recital the Patimokkha in Buddhist sangha began.

VI. The First Council of Vinaya

The Vinaya rules were transmitted orally from time to time, including at the first council held by the sangha after the Buddha’s Great Nirvana. The real status of the Vinaya rules at the time of the Buddha is said to have been “memorized by those of his followers who specialized in the subject of discipline, but nothing is known for sure of what format they used to organize this body of knowledge during his lifetime.”[15]

After the Buddha’s Great Nirvana, the sangha, led by Thera Mahakassapa, made an effort to recite all the rules of Vinaya and dharma and established the contents of dharma-vinaya in Pali canon. Consequently, the Vinaya of today was organized into two main parts: 1) the Sutta Vibhanga, the “Exposition of the Text,” containing Vinaya texts dealing with the Buddhist monastic rules, and 2) the Khandhakas (Groupings), containing material organized by subject matter. The Khandhakas are divided into two parts: the Mahāvagga (Greater Chapter) and Cullavagga (Lesser Chapter). Bhikkhu Thanissaro noted in his Vinaya translation that “Historians estimate that the Vibhanga and Khandhakas reached their present form no later than the 2nd century B.C.E., and that the Parivara, or Addenda—a summary and study guide—was added a few centuries later, closing the Vinaya Pitaka, the part of the Canon dealing with discipline.”[16]

Conclusion

Examining the subjects from the early years of the Buddha—the early Buddhist ordination with three refuges, the establishment of Pratimoksa, the contents of Pratimoksa, the Uposatha days, and the first Council of Vinaya—provides a brief overview of the establishment of the Buddhist monastic code. A more intensive study of Vinaya Tipitaka would require delving deeper into the nature and various situations of each single rule. Clearly such a task would be extremely interesting for those interested in the Buddhist monastic code and Buddhist morality.

[1] Thanissaro Bhikkhu, trans. and ed., The Buddhist Monastic Code: The Patimokkha training rules translated and explained (Valley Center, CA: Metta Forest Monastery, 1998) 10.

[2] Phra Sasana Sobhana, “Introduction to the Patimokkha”; see Nanamoli Thera, trans., Patimokkha: The rule for Buddhist monks (Bangkok: King Maha Makuta’s Academy, 1969) 3.

[3] Sangarava Sutta, in Anguttara Nikaya; see Thera 7.

[4] H.R.H. Prince Vajirananavarorasa, The Entrance to the Vinaya (Bangkok: King Maha Makuta’s Academy, 1969) 2.

[5] Mahāvagga, Vinaya Pitaka, Ch. II.

[6] Sobhana; see Thera 11.

[7] Bhikkhu 13.

[8] W. Pachow, A Comparative Study of The Pratimoksa: On the basic of its Chinese, Tibetan, Sanskrit and Pali versions (Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass Publishers, 2000) 4.

[9] Ibid. 4.

[10] Sobhana; see Thera 13.

[11] Pachow 11.

[12] This includes several texts and stories of great disciples who joined the sangha as well as the rules for ordination, the reciting of the Patimokkha during Uposatha days, and various procedures that monks are to perform during formal gatherings of the community. See Bhikkhu.

[13] Sobhana; see Thera 4.

[14] Sobhana; see Thera 9.

[15] Bhikkhu 13-14.

[16] Ibid. 14.