From Hinayana to Theravada: Ven. Alubomulle Sumanasara’s Mission to Japan

From Hinayana to Theravada: Ven. Alubomulle Sumanasara’s Mission to Japan

Dr. Kieko Obuse

Department and Affiliation

College of Religious Studies

Mahidol University, Thailand

Abstract

This paper examines introductory works on Theravada Buddhism by the Sri Lankan-born Ven. Alubomulle Sumanasara (1945- ), who has recently enjoyed considerable popularity in Japan. It discusses how he has dealt with the task of creating a positive interest in Theravada Buddhism in a society where it has long been regarded as ‘hīnayāna.’ It highlights that this goal has been achieved through a gradual process, in which he has constantly renegotiated his rhetoric and terminology in response to the changes in Japanese awareness of Theravada Buddhism.

Keywords: Theravada Buddhism, Japan, Alubomulle Sumanasara, Hinayana

Introduction: Promoting Theravada Buddhism in a Mahayana Society

The past few decades have seen an enormous increase in interest in Buddhism outside Asia. The active interest in Buddhism found in ‘New Lands’ has elicited the keen attention of scholars, who are now investigating how Buddhism has been received by, and adopted to these new host societies.[1] Attempts have also been made by countries possessing a longstanding tradition of Buddhism to ‘export’ their brands of Buddhism to other parts of Asia. As the host society is already familiar with Buddhism of some kind, these initiatives involve a different set of challenges from that faced by those promoting Buddhism outside Asia.[2] The present paper discusses the attempt made by the popular author Sri Lankan-born Ven. Alubomulle Sumanasara (1945- ) to promote Theravada Buddhism in Japan.[3] Through analyzing the ways he presents Theravada Buddhism in his introductory books on the tradition, the paper highlights how he has dealt with the task of creating a positive interest in Theravada Buddhism in a society where it has long been regarded as ‘hīnayāna’ (J: shōjō, the small, or lesser, vehicle). It is virtually the first academic attempt to examine Ven. Sumanasara’s works, and is intended to provide foundations for more comprehensive research on his activities, and on the Theravada Buddhist presence in Japan.[4]

1. The Limited Nature of the Japanese Involvement with Theravada Buddhism

Japanese involvement with Theravada Buddhism has historically been limited. Although some ethnic Japanese have taken up robes in Sri Lanka, Thailand, and Burma, they have not succeeded in establishing a solid indigenous Sangha in Japan.

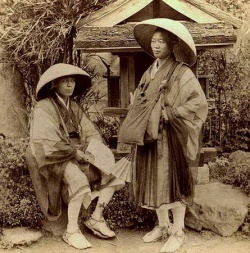

The first proper attempt to introduce Theravada Buddhism in Japan dates back to the late nineteenth century, over a millennium after Buddhism was first introduced to Japan. The first Japanese Theravada Bhikkhu was Kōnen Shaku (1849-1924) from the Shingon tradition. He travelled to Sri Lanka in 1893 to start his training.[5] He was ordained in Kandy in 1890, with the ordination name Gunaratana. Back in Japan, Kōnen founded the Shakuson Shōfū Kai (lit: the Society of the Right Wind, i.e. Way, of Śākyamuni) in 1893, in order to introduce Theravada Buddhism to Japan. To establish an ethnic Japanese Sangha, he also sent a few more Japanese monks to Sri Lanka to be ordained. However, Kōnen’s attempt to maintain the Theravada monastic lifestyle met with strong resistance from his (former) master in the Shingon tradition.[6] Although his enterprise gained some momentum when he was invited to Thailand (then Siam) in 1907, returning in the following year with a copy of the Thai Tipitaka and over fifty Buddha statues, it never came to fruition.[7]

One of the major factors in the frustration of Kōnen’s project seems to have been the traditional Japanese perception of Theravada as ‘Hīnayāna.’[8] The sense of superiority towards Theravada Buddhists was indeed not unusual among Japanese Buddhists around this time. The Rinzai Zen master Sōen Shaku (1860-1919), who also trained in the Theravada tradition in Sri Lanka for three years from 1887,[9] claimed to have refrained from conveying his understanding of Zen to his fellow ‘Hīnayāna’ monks, deeming it beyond their capacity.[10]

The nomenclature ‘Hīnayāna’ has continued to be employed in contemporary Japan to refer to Theravada Buddhism. Despite the scholarly consensus that it is a pejorative term coined by Mahayanists, the transition from using Hīnayāna to using Theravada has just only begun to take effect in popular understanding.[11]

Contemporary Japanese involvement with Theravada Buddhism takes place both in and outside Japan.[12] The country now has a number of organizations and temples related to the Theravada tradition. However, these tend to either cater for migrant Buddhists from South and Southeast Asia, or function as meditation centers, which do not usually aim to promote the Theravada Buddhist tradition as a whole.[13] Notable Japanese Bhikkhus active outside Japan include Phra Mitsuo Kavesako (1951-) of Wat Sunandavanaram, and Phra Yuki Narathevo (1962-) of Wat Pa Sukhato, both ordained in Thailand. They operate in a traditional Thai Theravada context, although they regularly receive visitors seeking spiritual guidance from their homeland.[14] Their influence on the spread of Theravada Buddhism in Japan is still limited, in part at least because they are not based in the country, which in itself suggests the difficulty in maintaining a traditional Theravada monastic life in Japan.[15] This makes the activities of Ven. Sumanasara those most clearly geared towards the promotion of Theravada Buddhism to the Japanese, among Theravada organizations and individuals originating from or present in Japan.

2. Ven. Sumanasara’s Involvement with Japan

Ven. Alubomulle Sumanasara was born in 1945 in Sri Lanka. He became a novice at the age of thirteen, and received full ordination in 1965. He studied at the Kelaniya University, and taught Buddhist philosophy there after graduation. When he came to Japan as a national scholarship student in 1980, he did not know much about Japan or Japanese Buddhism. After studying Japanese for a year, he enrolled at Komazawa University as a doctoral student. There he conducted research on Dōgen (1200-1253), the founder of the Soto Zen tradition. Upon completing his doctorate in 1988, he decided to focus on the teachings of the Buddha.[16] After teaching in both Japan and Sri Lanka for a few years, Ven. Sumanasara returned to Japan in 1991 to start teaching regularly. He established the Japan Theravada Association in 1994 (later renamed the Japan Theravada Buddhist Association). His initiative has also been acknowledged by the Sangha back in Sri Lanka. In 2005, Ven. Sumanasara was appointed Thera of the Japan Mahasanghanakaya at the Asgiriya temple, the headquarters of the Siam Nikaya.[17]

The Japan Theravada Buddhist Association is located in the Shibuya district of Tokyo. It is registered as a Religious Cooperation (J: shūkyō hōjin). The Association is housed on the Gōtami Vihara, where regular meditation sessions and study groups take place.[18] While these events are free and open to the public, the Association also provides a paid membership to interested individuals. Members receive a monthly copy of the Patipadā, the first journal dedicated to Theravada Buddhism, founded in 1995.[19]

The exact number of ethnic Japanese Theravada Buddhists is not known. It was reported that the Association had 1,500 members in 2008.[20] The figure must have grown since then, given the recent popularity of Ven. Sumanasara’s publications. While his activities with a group of Japanese ‘converts’ are certainly noteworthy,[21] it is primarily through his publications for general readership that he is known to the Japanese.

Ven. Sumanasara is an extremely prolific writer. He has published over 100 books in Japanese since the mid-1990s. Some are collections of short Dhamma talks, in which he quotes teachings of the Pali Canon, such as the Dhammapada, applying them to contemporary social life. Others deal with meditation, mainly the Vipassana meditation of the Mahasi strand, which focuses on labeling. Combined with this, the practice of compassion (J: jihi, Pali: metta) is also often introduced.[22] The popularity of his books is remarkable, considering the literature on Theravada Buddhism in Japanese is extremely limited. Nowadays, major bookshops keep a few shelves belonging to the section on religion or on Buddhism just for his publications.[23]

The main focus of Ven. Sumanasara’s writings is on managing one’s life, work, and human relationships. Presented as practical guides, they are written in an accessible style, although the content can sometimes be technical, drawing, for example, on the Abhidhamma. The most successful of his works is Okoranaikoto [On Not Being Angry, or No Anger), which is a work in two volumes (2006 and 2010). It has sold over half a million copies (counting both books separately).[24] This best-seller explains how one can manage the difficulty in one’s life by understanding how the mind functions. Identifying anger to be the root of one’s life, hence of all its problems, the author encourages the reader to understand and overcome it with the practice of metta.[25]

3. From Hinayana to Theravada

There are various possible reasons for the popularity of Ven. Sumanasara’s books, for example his command of Japanese language and communication skills, or his ‘exotic’ background. It is also possible that those dissatisfied with religious traditions already present in Japan are turning to Theravada Buddhism as a potential alternative. However, what appears to be his essential achievement is addressing the negative connotation of the label ‘Hīnayāna,’ presenting Theravada Buddhism as having special significance to people with a Mahayana centered perception of Buddhism, thereby making Theravada Buddhism accessible to the Japanese.

Among the numerous publications of Ven. Sumanasara, only three of them carry the term ‘Theravada Buddhism’ (J: Jōzabukkyō or tērawāda bukkyō) in the title. However, they reveal clearly how Theravada Buddhism has been (re-)introduced through his publications. The first two were published in the late 1990s during the early stage of his career, and the third in 2010, after he had achieved publicity in Japan. That these three books were all published by Daihōrinkaku, a leading Japanese publisher specializing in Buddhism, also indicates that there has been a substantial willingness among Japanese Buddhists to disseminate information about Theravada Buddhism through Ven. Sumanasara’s writings amongst a wider Japanese Buddhist readership.[26]

Ven. Sumanasara’s first introductory book on Theravada Buddhism is The First Book [of] Jōzabukkyō: Life-Changing Teachings of the Buddha (1998).[27] The wording of the main title suggests that the author regards the work as the first book to properly explain the teachings of Theravada Buddhism to the Japanese. It is not simply ‘an introduction’ to Theravada Buddhism amongst many others. It opens by warning against the danger of blind belief and conformity to social conventions, arguing for the importance of critical thinking and independent judgment. Resonating with the message of the Kalama Sutta, Ven. Sumanasara quotes the Buddha: ‘Don’t just believe everything, even if it is what your teacher says.’[28] The book is primarily about mind, with its five chapters discussing how the mind functions and produces suffering, and how one can cultivate one’s mind to attain a happier life. In the end of the book, the practice of Vipassana meditation is introduced as a means to remove one’s ego-centeredness and to attain an objective perspective on the world.[29]

Although the book claims to provide the teachings of the Buddha, hence of Theravada Buddhism, it does not clarify how they differ from those of Japanese Buddhism. The introduction begins with a declaration that ‘ninety percent of the Buddhism that was taught by Oshakasama (i.e. Śākyamuni) deals with matters concerning mind.’[30] This implies that the Buddhism known in Japan is different from the Buddhism taught by Śākyamuni. However, the position of Theravada Buddhism vis-à-vis the Mahayana traditions of Japan is not fully articulated.

Ven. Sumanasara’s second book, Jōzabukkyō: Towards an Enlightened Life, immediately followed his first, being published in 1999.[31] Co-authored by Issei Suzuki (1947-), the founder and first president of the Japan Theravada Buddhist Association, it seems to attempt to rectify the lack of clarity the previous work suffered concerning the significance of introducing Theravada Buddhism to the Japanese, thereby setting a clearer agenda for the reader. Like its predecessor, this book claims to provide a completely different perspective on life. The content is slightly more practical, with more concrete suggestions on how to deal with challenges of life. The potentially life-changing effect of the book is amply suggested by the use of the word ‘Satori’ in the sub-title, which is a generic term to refer to enlightenment, or realization of the truth.[32] The simplicity of the main title Jōzabukkyō helps make a direct connection between Theravada Buddhism and enlightenment. Thus, the title can be said to be intended to imply that Theravada Buddhism provides the path towards enlightenment par excellence.

The authors’ willingness to establish the ‘correct’ understanding of what Theravada Buddhism is and to clarify its significance, is clear from the manifesto-like statement placed at the very beginning of the book. The importance of this statement is also evident from the way it is presented in horizontal writing in order to catch the attention of readers, with bold lines placed both on top and at bottom of the text (while the rest of the book is in vertical writing). For the purpose of simplicity and convenience, what follows discusses it in four parts (my translation).

1. Jōzabukkyō represents the teachings that Oshakasama left about 2,500 years ago. They have been passed down by many Bhikkhus, renunciation monks who practice his teachings. This tradition is called tērawāda in Pali, and is known in Japan by such names as Konpon bukkyō (fundamental Buddhism), or shoki bukkyō (early Buddhism), or genshi bukkyō (original/primitive Buddhism).

It is emphasized throughout the statement that the teachings of Theravada Buddhism are identical to those of Śākyamuni Buddha, and hence are the ‘genuine’ Buddhism. This challenges the popular Japanese perception of Theravada Buddhism as ‘Hīnayāna.’ However, the authors employ an indirect approach to rectifying this ‘misperception.’ They simply introduce its name in Pali, followed by various Japanese terms for it. The omission of the most commonly used term, Hīnayāna, is striking, and clearly deliberate.[33] This may suggest the authors’ firm refusal to acknowledge any connection with what is called Hīnayāna, although the absence of reference to the term would certainly seem odd to any Japanese reader with some knowledge of Buddhism. The omission may be a deliberate strategy employed by the authors to make the reader question their self-representation, thereby heightening the impact when they finally reveal their stance concerning the term. It is also possible that they are cautious not to criticize Japanese Buddhism or the Japanese view of Theravada Buddhism early on in the work, for fear of discouraging the reader.[34]

2. As you know, Buddhism was originally taught by Oshakasama. However, his teachings were divided into many different strands over the course of time, and have had an evercontinuing history of development. They were introduced to Japan in the form of Daijō bukkyō in the Asuka period,[35] which points to the fact that Buddhism developed after Oshakasama’s demise (J: nyūmetsu, Pali: parinibbāna), moving in various directions, some of which are not necessarily congruent with his authentic teachings. This fact is evidenced, for example, by the distinction made between Daijō bukkyō and Shōjō bukkyō.

In the second part, it is argued again, through a brief historical account, that Buddhism derives from the teachings of Oshakasama, which have gone through various developments, resulting traditions being eventually called either Mahayana or Hīnayāna. The main point, which is repeated more explicitly later, is that the Buddhism introduced to Japan does not represent the genuine teachings of the Buddha.[36]

3. Jōzabukkyō is neither daijō or shōjō. It has transmitted the teachings and practices as taught by Oshakasama in their original forms in unbroken lineage until today. There is not a single modification, [ungrounded] inference or interpretation added to them. In other words, they are the genuine teachings of Oshakasama. 1,500 years on from the arrival of Buddhism in Japan, why have these teachings not been introduced to Japan, a nation with a highly developed Buddhist tradition?!

What follows is a simple declaration that Theravada Buddhism is neither Mahayana nor Hīnayāna. The authors attempt to substantiate this claim by repeating that their tradition represents the unmodified teachings of Śākyamuni. It is only at this point that they insist that the Japanese have missed out on the genuine message of the Buddha. Again, they are fairly careful not to offend their Japanese readers. The fact that the Japanese have not received Theravada Buddhism is presented as an unfortunate accident, and not due to their misjudgment or closed-mindedness. The authors also express their appreciation for Japanese Buddhism, calling it ‘highly developed’ (J: kōdona, lit: of high level).[37] The message is that Japanese Buddhism has much to offer, but Theravada Buddhism offers even more!

4. Oshakasama’s teachings and his method of practice, i.e. Vipassana meditation, provide a path, a method to attaining happiness. They can be practiced by any human being, regardless of sect or religious affiliation. It is our wish that the readers will understand the truth of the universe and life through these teachings, and so live happily in the forthcoming millennium.

The authors finally introduce what they view as the main content of their tradition, Vipassana meditation, in the last part of the statement. That the Buddha’s teachings provide a method of generating a proper understanding of the world and of realizing happiness in life is the point Ven. Sumanasara makes repeatedly in his works.

The statement amply reflects the sensitive nature of the authors’ project to introduce Theravada Buddhism to a predominantly Mahayana readership. It is rather repetitive at times, showing the authors’ struggle to clarify the position and significance of Theravada Buddhism without discouraging their Japanese audience. As if to compensate for the lack of information the manifesto has about the possible impact of Theravada teachings and practices, a tagline is placed after the table of contents, right before the main text, warning readers of the radical, transformative nature of the information to follow. It reads: ‘What you are from today on will be different from what you were up to yesterday.’

The third introductory book on Theravada Buddhism by Ven. Sumanasara is entitled Theravada Buddhism: Seeing [lit. Confirming] the Buddha’s Teachings [to be the Case] for oneself (2010).[38] It provides a more comprehensive account of the Theravada tradition, articulating what the author regards the main aspects of Theravada Buddhist practice. By this time, Ven. Sumanasara had established his career as a Theravada teacher in Japan. Published in 2010 amidst the popularity of his Okoranaikoto, it is highly possible that this work was a renewed attempt to introduce his tradition properly. For the first time, the Pali term Theravada (J: tērawāda) is used in the title of the book, instead of jōza. Perhaps the time had come when he felt it possible to present Theravada Buddhism more on its own terms, needing fewer adaptations to make it accessible to a Japanese audience.[39]

Like the previous works, his third book begins by emphasizing that the Buddha’s teachings have scientific validity, being ‘a science of mind.’ Its chapters discuss central teachings and practices associated with Theravada Buddhism. The topics range from the importance of seeing things for oneself, practical advice on lay life and how to improve a society, to more ‘classic’ themes such as the Noble Eightfold Path, the Four Noble Truths, and even to monastic life. Particularly remarkable is the work’s focus on the five precepts, the discussion of which takes up seven out of the twenty-four chapters, presenting them as vital components of the tradition. In this volume Theravada Buddhism has finally received a comprehensive treatment as a religious tradition[40] rather than being treated simply as a method of understanding the world and getting most out of life, or as ‘Hīnayāna.’[41] As such, this book signals a milestone achievement in Ven. Sumanasara’s mission to Japan.

4. Conclusion

This paper has examined how Ven. Sumanasara dealt with the task of correcting the traditionally negative Japanese perception of Theravada Buddhism as ‘Hīnayāna’ and set about creating a more positive understanding of the tradition. This goal has been achieved through a gradual process, in which he has constantly renegotiated his rhetoric and terminology in response to changes in Japanese awareness of Theravada Buddhism. It may now be possible to say that Ven. Sumanasara’s works have laid a foundation for the Japanese to accept Theravada Buddhism more on its own terms. It remains to be seen if and to what extent this increased appreciation of the Theravada worldview will lead to an active interest in establishing a Theravada Buddhist community centered around a monastic Sangha.[42]

Bibliography (books and articles only)

Alubomulle Sumanasara. Kokoroga Futto Karukunaru Budda no Meisō, Daiwashobō, 2010.

―― Tērawāda Bukkyō: Mizukara Tashikameru Budda no Oshie, Daihōrinkaku, 2010.

―― Hajimete no Hon Jōzabukkyō: Jōshikiga Ippensuru Budda no Oshie, Daihōrinkaku, 1998.

Alubomulle Sumanasara and Issei Suzuki, Jōzabukkyō: Satorinagara Ikiru, Daihōrinkaku, 1999.

Fields, Rick. How the Swans Came to the Lake: A Narrative History of Buddhism in America, 3rd edition, Shambala, [1981, 1986] 1992

Fujimoto, Akira. Satori no Kaitei: Tērawādabukkyō ga Akasu Satori no Kōzō, introduction by Alubomulle Sumanasara, Samgha, 2009.

Gakken Mook, Budda no Okurimono (The Gift from Buddha): Sumanasārachōrō to Shokibukkyō no Sekai, Gakken Publishing, 2011.

Higashimoto, Keiki. “Shakuson Shōfukai no Hitobito” [On the Buddhist Monks of the Shaku-Son-Sho-Fu-Kai] Journal of the Faculty of Buddhism of the Komazawa University 40, 1982-3: 51-61.

McRae, John R. “Oriental Verities on the American Frontier: The 1893 World’s Parliament of Religions and the Thought of Masao Abe” Buddhist-Christian Studies 11, 1991: 7-36.

Morrow, Avery. “The Past and Present of Theravada Buddhism in Japan” (unpublished paper, 2008) ‘Essays – Unpublished papers’ < http://avery.morrow.name/studies/ >.

Narathevo, Phrayuki. Kurushimanakute Īndayo: Kokoro Yasurakani Ikirutameno Budda no Chie, PHP, 2011.

―― Kidzuki no Meisō” o Ikiru: Tai de Shukkeshita Nihonjinsō no Monogatari, Kōsei Shuppansha, 2009.

Samgha Publisher, “Special Feature: Jōzabukkyō to Daijōbukkyō” Samgha Japan 9, March 2012.

Sato, Tetsuo. Daiajia Shisō Katsugeki: Bukkyō ga Musunda, Mouhitotsu no Kindaishi, Samgha, 2008.

Footnotes

- ↑ The panel “Teaching Dhamma in New Lands,” convened for this year’s International Association of Buddhist Universities conference, is a good example of this inquiry.

- ↑ Thus, it does not deal with those catering for the migrant community of their own tradition abroad.

- ↑ The recent publication of journals featuring Ven. Sumanasara and Theravada Buddhism clearly demonstrates the growing interest in them in Japan. See “Special Feature: Jōzabukkyō to Daijōbukkyō” Samgha Japan 9 (March 2012); Gakken Mook, Budda no Okurimono: Sumanasārachōrō to Shokibukkyō no Sekai (Tokyo: Gakken Publishing, 2011).

- ↑ His publications have so far not been translated into English nor examined properly by academic scholarship. Avery Morrow, “The Past and Present of Theravada Buddhism in Japan” (unpublished paper, 2008) ‘Essays – Unpublished papers’ < http://avery.morrow.name/studies/ > [accessed 25/03/2012], 17.

- ↑ The possibility of sending Japanese monks to Sri Lanka to study the Theravada tradition materialized through the initiative of Jodo-Shin monk-scholars who visited the island as part of their journey to Great Britain. Tetsuo Sato, Daiajia Shisō Katsugeki: Bukkyō ga Musunda, Mouhitotsu no Kindaishi (Tokyo: Samgha, 2008), 208-9. Keiki Higashimoto, “Shakuson Shōfukai no Hitobito” [On the Buddhist Monks of the Shaku-Son-Sho-Fu-Kai] Journal of the Faculty of Buddhism of the Komazawa University 40 (1982-3): 51-61. See 52.

- ↑ Higashimoto, “Shakuson Shōfukai,” 57-58.

- ↑ Higashimoto, “Shakuson Shōfukai,” 59.

- ↑ Sato, Daiajia Shisō Katsugeki, 222.

- ↑ He gave a speech at the World’s Parliament of Religions in Chicago in 1893, laying foundations for the introduction of Zen Buddhism to the West, through his disciple Daisetz Suzuki (1870-1966).

- ↑ John R. McRae, “Oriental Verities on the American Frontier: The 1893 World’s Parliament of Religions and the Thought of Masao Abe” Buddhist-Christian Studies 11 (1991): 7-36, see 25, quoting Rick Fields, How the Swans Came to the Lake: A Narrative History of Buddhism in America, 3rd edition (Boston and London: Shambala, [1981, 1986] 1992), 110. However, he was impressed by the way ‘the monks keep the Precepts strictly and act as examples of the ethical life for the rest of the people,’ adding that he was ‘ashamed’ when he thought ‘of the Japanese Buddhists, both priests and adherents.’ McRae, ibid, quoting Fields, 112.

- ↑ See, for example, Encyclopedia of Buddhism, ed. Robert E. Buswell (New York: Macmillan, 2004), s.v. “Hīnayāna” (vol.1: 328). Moreover, the majority of Japanese scholars of Buddhism focus on Mahayana Buddhism. Those who read Pali tend to conduct philological studies of early sources, showing very little interest in Theravada Buddhism as practiced in contemporary times.

- ↑ The author is grateful to Miss Kanae Kawamoto for providing initial information for this section.

- ↑ For example, see Japan Vipassana Association, < http://www.jp.dhamma.org/index.php?id=1164&L=12 > [accessed on 19/04/2012].

- ↑ The activities of Phra Yuki are now known to the Japanese through his publications, in which he explains Thai Buddhism and its meditation practices. See Phrayuki Narathevo, “Kidzuki no Meisō” o Ikiru: Tai de Shukkeshita Nihonjinsō no Monogatari (Tokyo: Kōsei Shuppansha, 2009), and Kurushimanakute Īndayo: Kokoro Yasurakani Ikirutameno Budda no Chie (Tokyo: PHP, 2011).

- ↑ One interesting exception is Ven. Ryodo Yamashita (c.1960-), who is ordained in both Theravada (Burmese) and Soto Zen traditions. He takes an ecumenical approach, teaching meditation drawing on both Theravada and Mahayana perspectives. Ippōan: One Dharma Forum < http://www.onedhamma.com/ > [accessed on 19/04/2012].

- ↑ Gakken Mook, “Special Interview: Sumanasāra Chōrō, Hansei to Bukkyō o Kataru” Budda no Okurimono, 59.

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ It also functions as a residence for Japanese Theravada monks, who have been ordained in South Asia. They also have a few other Viharas in Japan now, inhabited by immigrant Theravada monks. Morrow, “Theravada Buddhism in Japan,” 10. For a brief English account of the Gotami vihara, see < http://www.jtheravada. net/gotami.html > [accessed 02/04/2012].

- ↑ It features dhamma talks by Ven. Sumanasara, Japanese translations of the Pali Canon, and information on events organised by the Association. For more on their activities, see Japan Theravada Buddhist Association, < http://www.j-theravada.net/index.html > [accessed 02/04/2012]. Most of the information on their webpage, unfortunately, is only available in Japanese.

- ↑ Morrow, “Theravada Buddhism in Japan,” 10.

- ↑ One of the rare research papers on Japanese converts to the Theravada tradition is Naoko Takahashi, “Nihonni okeru Terawada Bukkyo Jissensha no Kaishin Purosesu to Shiseikan” Shiseigaku Kenkyu [Construction of Life and Death Studies] 7 (2006), 487-482.

- ↑ See, e.g. Alubomulle Sumanasara, Kokoroga Futto Karukunaru Budda no Meisō (Tokyo: Daiwashobō, 2010), 44.

- ↑ One of the few books written by a Japanese author on Theravada Buddhism is Akira Fujimoto, Satori no Kaitei: Tērawādabukkyō ga Akasu Satori no Kōzō, introduction by Alubomulle Sumanasara (Tokyo: Samgha, 2009). That the book is introduced by Ven. Sumanasara suggests that the publication of a book on Theravada Buddhism is deemed marketable only when authenticated by him.

- ↑ Alubomulle Sumanasara, Okoranaikoto (Tokyo: Samgha, 2006) and Okoranaikoto 2 (Tokyo: Samgha, 2010).

- ↑ Sumanasara, Okoranaikoto 2, 226f.

- ↑ Their catalogue has a section on Theravada Buddhism. Five of the six items listed there are written by Ven. Sumanasara, while the sixth is a book on the Pali Canon authored by a Japanese scholar. This suggests that Ven. Sumanasara has been regarded as the foremost, if not the only, contemporary authority on Theravada Buddhism in Japan. See Daihōrinkaku, Bukkyōsho Bunyabetsu Risuto (Japanese only), < http://www.daihorin-kaku.com/book/index.html > [accessed on 19/04/2012].

- ↑ Alubomulle Sumanasara, Hajimete no Hon Jōzabukkyō: Jōshikiga Ippensuru Budda no Oshie (Tokyo: Daihōrinkaku, 1998).

- ↑ Sumanasara, Hajimete no Hon, 2.

- ↑ Ibid., 233.

- ↑ Ibid., 1.

- ↑ Alubomulle Sumanasara and Issei Suzuki, Jōzabukkyō: Satorinagara Ikiru (Tokyo: Daihōrinkaku, 1999).

- ↑ It can denote the perceptional breakthrough experienced in Zen traditions, as well as the nirvana of the historical Buddha. While it may be used in mundane everyday contexts, it is widely recognized as a term for the highest spiritual attainment in Buddhism. The sub-title literally means ‘living while progressing towards enlightenment’ or more idiomatically ‘living on the path to enlightenment.’

- ↑ None of the terms listed denotes the Theravada tradition as such, but is a more general category referring to the Buddhism practiced after the time of the Buddha. However, Theravadins tend to claim their tradition to be ‘original Buddhism,’ preserving faithfully the teachings of the Buddha. Ven. Sumanasara’s stance is no exception. Encyclopedia of Buddhism, s.v. “Theravada,” esp. 837.

- ↑ The use of the Japanese name Oshakasama (lit: honorable shaka, i.e. Śākyamuni) to refer to the historical Buddha, Gotama also suggests the authors’ attempt to make their message accessible to Japanese readers, who tend to only know the Buddha by that term.

- ↑ The Asuka period is 592-710.

- ↑ It is interesting that, in trying to dismiss the Mahayana/hīnayāna distinction, the authors do not say that these categories were propounded by Mahayanists in establishing their own stance vis-à-vis the traditions that had been mainstream. It may be that they regarded such details as too technical to be included.

- ↑ Given the sharp criticism that Ven. Sumanasara makes elsewhere of Japanese and Mahayana Buddhism, he is clearly merely paying lip-service here, as a strategy to encourage interest in Theravada Buddhism. See, for example, Morrow, “Theravada Buddhism in Japan,” 12-13. Also see note 40 below.

- ↑ Alubomulle Sumanasara, Tērawāda Bukkyō: Mizukara Tashikameru Budda no Oshie (Tokyo: Daihōrinkaku, 2010).

- ↑ Perhaps for the same reason, he openly criticises Japanese Buddhist monks in the book, especially for their failure to observe the five precepts. Sumanasara, Tērawāda Bukkyō, 40, 116.

- ↑ Although he often argues that Buddhism is not a religion, in that it is radically different from other religious traditions, this paper regards (Theravada) Buddhism as a fully-fledged religious tradition.

- ↑ It is, however, to be noted that certain aspects of the tradition, such as the idea of karma and rebirth and the practice of merit-making, which assume much importance in South and Southeast Asian Theravada societies, are rarely mentioned. This is perhaps because they are deemed less appealing to the Japanese and hence not so conducive to the promotion of the tradition in Japan. This selective approach also seems to be found among those teaching Theravada Buddhism in the West.

- ↑ In the meantime, more detailed research is needed to paint a comprehensive picture of Ven. Sumanasara’s teachings, especially his views of Mahayana Buddhism, and to critically evaluate them. It is also essential to examine how his writings have been received by both lay and ordained Buddhists in Japan. Investigation also needs to be conducted on the nature of the ethnic Japanese Theravada community, and what connections they have with Theravada communities outside Japan in order to maintain and develop their practice.

Source

Dr. Kieko Obuse

Department and Affiliation

College of Religious Studies

Mahidol University, Thailand

academia.edu