Guardian deities in Tibet

[[Category:]]

GUARDIAN DEITIES IN TIBET (author to be ascertained - Jampa Namgyal 2009 12 20) Table of Contents Acknowledgements 2 Illustrations 3 Introduction 5 First Kora: A Brief

Orientation 9 At the Threshold 14 Second Kora: The Demoness Subduing Temple 28 The Origin of Tibetan Guardians 35 Third Kora: The Ambition of Guardians 52 The Guardian Image 61 Conclusion 70 Notes 73 Glossary 78 Works Referenced 82 Credits 85 Map of Tibet 86 Acknowledgements

The production of the following essay was a defining experience for me and I would like to thank the people and organizations that made it possible. First, I am indebted to my advisors Bernard Faure and Mark Mancall, as well as to Hilton Obenzinger, all of whomwere patient with me and my ignorance. Thanks to the Undergraduate Research

Office, and the Institute for International Education for their generous funding, especially to Richard Goldie who directly sponsored my project. I would also like to thank

James Russell and Liu Zhijun, who traveled with me and shared in my experiences. I am deeply grateful to Sha Wu-tian, an archeologist who gave me free access to the

magnificent caves at Dunhuang, and to Pema Chodring, a monk at the Jokhang. I also owe much to my roommates, Ben Cain, Scott Loarie, and Tom Soule, who tolerated me while

writing this thesis. Most of all, I would like to thank the multitude of people in Tibet and in China who shared with me their kindness, and facilitated my journey and research.

Finally, I would like to thank my family both for extensive help with Indian mythology and for worrying about me while in Tibet.

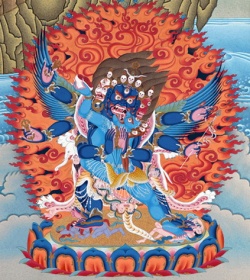

Illustrations XXXVII.Mahakala - Chakdrupa. Mahakala , 'the great black one', is a major dharmapala in Tibet. This Thangka is an 18th century Thangka from the Collection of Shelley & Donald Rubin Foundation, at www.tibetart.com. XXXVIII.Wrathful face of a Guardian. The furious face of a typical guardian, taken from a frescoe on the roof of the Jokhang.

Photograph by Kumar Narayanan XXXIX.Front Gates of the Jokhang. The Jokhang is the 'Cathedral of Lhasa', located in the Barkhor area. Photograph by James Russell.

XL.Vajrapani.The thunderbolt protector, called Channan Dorje in Tibetan, also from the third floor of the Jokhang. Photograph by Kumar Narayanan XLI.Dvarapala.A gate guardian dating from 6th century from South India, Chalukya Dynasty. These guardians of the gate typically appear in flanking position of major doorways.

XLII.Narasimhan.Line image of Narasimhan, Fifth Avatar of Vishnu. Notice how he is in between two pillars. XLIII.The Dalai Lama's camp. A beautiful picture of the Dalai Lama's traveling camp, taken in 1939 just outside of Lhasa. Notice the concentric circles, and the striking resemblance to a mandala. Taken from Rolf Stein's Tibetan Civilization, p39

XLIV.Bhavachakra. Wheel of Life from the 16th century. Yama, (or Samsara) is in the background, holding up the wheel. From www.tibetart.com. XLV.Avalokitesvara Mandala. Mandala depictingBar do, with 100 wrathful deities on the periphery,and 100 peaceful deities in the next inner layer. Avalokitesvara is the main deity. From www.tibetart.com. XLVI.Gyantse Kumbum: The Kumbum at Gyantse, looking up from below. Photograph by Kumar Narayanan. XLVII.Mandala on a Doorway. A mandala scroll on a household doorway in Gyantse. Photograph by Kumar

Narayanan. XLVIII.Household Doorway. A doorway to a Tibetan household in the town of Tsetang.

Notice the ornate scrollwork and fierce imagery that adorns the doorway. There are wrathful images on the doorframe. Photograph by Kumar Narayanan.

XLIX. Han Guardians. Two common figures on Han Chinese doorways. These two Taoist kings are clearly guardians of some sort. Photo taken in Dunhuang, Gansu,by Kumar Narayanan. L.Dunhuang Guardians.Two guardians from the magnificent caves of Dunhuang. The right guardian is a dvarapala from cave X, and the left guardian is a lokpala from cave X. Guardians are presentative of late T’ang, and S’ung dynasties. Photographs courtesy of Sha Wu-tian. LI.Jokhang Roofline. The roofline of the Jokhang, bronze spires in glistening in midday.

Photograph by Kumar Narayanan. LII.Cairn. A cairn with prayer flags at Nam Tso lake, Tashi Dor area. Notice the size of the cairn (I am seated to the right). Photograph by James Russell. LIII.Summit Cairn. A cairn above Ganden Monastery. This cairn sits at the highest point on a ridge above Ganden at some 15,000 feet. From it, you can see the entire Kyichu (Lhasa) river valley. Photograph by Kumar Narayanan.

LIV.Drukpa Kunley. A picture of the divine madman. Illustration taken from The Divine Madman, by Keith Dowman. LV.Terracotta Warrior. An member of the terracotta army of Qin Shi Huang, standing watch over his grave. LVI.Yumbulungang. Rumored to Tibet’s first castle, the Yumbulungang dominates the barley fields of the Yarlung Valley, the cradle of Tibetan

Civilization. Notice its key placement. Photography by Kumar Narayanan LVII.Guardian of a Field. A curious image from Kong-Po, taken by Sir G.Taylor, of a guardian in the

middle of a field around 1930. Image taken from David Snellgrove and Hugh Richardson s The Cultural History of Tibet. LVIII.Masks of Trandruk Monastery s Gonkhang.A host of wrathful masks that line the threshold at Trandruk Monastery, in the Yarlung Valley. These masks have little to do with Buddhism. Photograph by

Kumar Narayanan.

LIX.Our Lady of Guadoulope.A picture of the dark skinned Latin American rendition of the Virgin Mary. This major religious figure is a typical example of syncretism in Latin American Catholicism. LX.A Wrathful Dancer. Ritualistic dance during a festival, wearing the mask of a wrathful deity. This image suggests another element of the guardian deities outside of Buddhism. From Guiseppi Tucci sT ibet. LXI.Ganesa.An ivory statue of Ganesa from the Metropolitan Art Museum. LXII.Hayagriva. A picture of Hayagriva as appears in

early Indian art. From Robert Linrothe s Ruthless Compassion. LXIII.Yaksa.Image of a yaksa, the curious tutelary deities. From www.hindumythology.com LXIV.Dorje Shugden.A picture of Dorje Shugden, an ascendant protector of the Gelugpa tradition, and the center of an ongoing controversy in the Tibetan government. Picture from: http://www.shugden.com/.

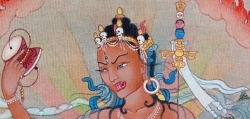

LXV.Pehar.Originally a minor protector, Pehar has rapidly ascended to position of a Yidam. Taken from Shelley and Donald Rubin Collection. Picture from: www.tibetart.com. LXVI.Palden Lhamo. Palden Lhamo appearing as a guardian in the protector s alcove of the Jokhang. Notice every one of her three sets of eyes is directed at the temple viewer. Photograph by Kumar Narayanan LXVII.Lokpala s Eyes. The gaze of a lokpala at the threshold is fixed on the temple pilgrim, establishing a transformative connection. LXVIII.Skull.A haunting skull on the third floor of the Jokhang. Photograph by Kumar Narayanan LXIX.Fire Scrollwork Detail.Section of ornate scrollwork that appears behind most guardians. Photograph by Kumar Narayanan LXX.Head of a Chinese Guardian.This is a Ming Dynasty Buddhist dvarapala cast in bronze, dating from about1600 BCE. From the collection of Sigmund Freud. Available at: http://www.kajima.co.jp/prof/culture/freud/. LXXI.Javanese Dvarapala Torso.Terracotta gate guardian dating from around the 14th Century BCE, Kingdom of Majapahit. On display at the Utah Museum of Fine Art, available at: http://www.utah.edu/umfa/panasian.html LXXII.Mahakala,Life size statue of guardian Mahakala in all his glory, at the gonkhang of Ganden Monastery. Photograph by Kumar Narayanan A Brief Orientation The classification of guardian deities in Tibet is characterized by complexity.

Both in India and in China, there are a few classes of guardians who fit neatly into categories, such as guardian of the gate , or guardian of direction . On the other hand, in

Tibet, there are not only several classes of guardians, but also numerous intersections between diverse representations of Tibetan guardians and protective deities

In my view, the definition is simple: deities that are classified as guardians are those who protect something, whether it is a person, place, idea, or doctrine.

Though such a definition might seem straightforward, there are guardians who have other roles beyond protection, as well as gods who are not guardians who confer protection.

The classification of a deity as guardian includes many rough edges. Still, I believe that there are defining features that identify as a deity as a guardian.

Guardian deities can easily be recognized by a combination of stereotypical location and wrathful features. Typically, their facial features are wrathful ,and it is possible to organize Tibetan deities strictly according to their demeanor.

In his beautiful book, Ruthless Compassion, Robert Linrothe introduces the category of krodha - vighnantaka (in Sanskrit ‘wrathful destroyer of obstacles’), or wrathful deities. Guardians are often wrathful, and share specific iconographical elements. InO r acles and Demons of Tibet, the classic compendium on the topic, Rene de Nebesky – Wojkowitz describes: The wrathful protective deities are mostly described as figures possessing stout bodies, short, thick and strong limbs and many of them have several heads and a great number of

hands and feet. The color of their bodies and faces is frequently compared with the characteristic hue of clouds, precious stones, etc…the mouth is

contorted into an angry smile, from its corners protrude long fangs…the protruding, bloodshot eyes have an angry and staring expression and usually a third eye is visible in the middle of the forehead These are some of the features that typify guardian deities of Tibet(see IV). Many others,such as their bright color, the furious dance on the back of a pathetic creature, and the fire that rages behind them, are consistent with their ferocity and fierceness. However, defining guardianship based strictly on wrathful iconography is problematic. Wrathfulness has a wide scope in Tibetan religion. All deities that manifest wrathfulness are not necessarily guardian deities; in fact, there is an entire group of

deities who display wrathfulness but who are not guardians. These deities, such as the isthadeva(tib. yidam), are important deities but they are not protectors, though they sometimes appear as guardians. Wrathfulness is a difficult concept, particularly for Westerners. In Tibet, wrathfulness is merely another side of compassion. For example,Avaloki tes var a or Manjushri might have a wrathful form just as they have a compassionate form. Though wrathfulness is not wholly unconnected from guardianship, it is perhaps a different subject entirely. The guardian image invokes the wrathful motif in particular ways, and the intersection between wrathfulness and guardians is a dimension of their complexity.

Linrothe organizes the relationship between wrathful deities into a single figure (see Figure 1). Relative status is the key dependent variable that differentiates between the

wrathful deities. Guardians are considered to be of lower status than other wrathful deities. The profane status of guardian deities is related to another distinguishing feature: their placement. Typically, guardians appear on the periphery, at thresholds,outer walls, flanking major deities, or ingonkhangs, special protector chapels. There are several

classes of guardian deities, such as lokpalas, dvarapalas, and dharmapalas. Many of them have deep roots in India (see V), which we shall see has great relevance

in thinking about guardian deities of Tibet. The Indian guardians originated from the form of ayaks a, a curious tutelary deity that predated Vedic culture.Guardian deities followed the trajectory of Buddhism as it spread to the Kushans (in present-day Afghanistan), across the expansive Silk Road and into China during the first millenium. Though a developed conception of sacred space existed in China before the arrival Buddhism, there is little question that guardians arrived in their current form along with Buddhism via the Silk Road. Whether Tibetans first encountered Buddhism and its

guardians upon their early ravages of central Asia, through intermittent

official channels

with China and India, or through a slow diffusion of ideas over the Himalayas

remains

unknown. However, there can be no mistake regarding the transformation that

Buddhism effected upon Tibet. Buddhist protective deities were central players in this fundamental societal change. As in China, the guardians of Tibet arrived with Buddhism

However, I

hope to demonstrate that the source of the current guardian image originates in

the

dialogue between Buddhism and indigenous Tibetan tradition.

Perhaps the simplest guardian in temple architecture in Asia is the dvarapala,

which means gate guardian in Sanskrit. These guardians, who appear in pairs,

are often

related in mythical origin. They stand watch over important thresholds of major

deities.

At the Jokhang, there are several sets of dvarapalas at many thresholds, in

front of a few

chapels, as well as the Jowo Lhokhang, the chapel which housesJowo, the major

deity.

Most importantly, other Tibetan protectors can act in a similar capacity as the

dvarapalas

by simply appearing at the correct places.

A second class of guardian deities that hails from India are the lokpalas, who

maintain vigil over the cardinal directions. In Sanskrit, the names of lokpalas

are: Vaisravana(North), Virupaksha(Wes t), Dhrirastra (East), and

Virudhuka(South). They demarcate the edges of mandala, and sometimes appear in

temples watching over

their respective directions. Each of the guardians of north, west, east, and

south have

independent, beautiful mythologies. For instance, Vaisravana, also called

Kubera, is the

god of the north, and the god of wealth, and also fabled to be the king of the

yaksas.

However, the classification of lokpalas is not as neat as it is with the

dvarapalas. For

instance, in addition to their post at the cardinal directions at the Jokhang,

lokpalas appear

at the main gate. The place of lokpalas at the front gates is common throughout

Mahayana temples in China, where they are called the Guardian Kings . Also, the

lokapala image in Tibet is not always wrathful. At the outermost gate of the

Jokhang,

they lack the hallmark crown of five skulls, the third eye, or the distinctive

halo of fire.

However, in other renderings of lokpalas around Tibet and particularly in

mandala, it is

possible to observe wrathful renditions of lokpalas.

A more general classification of guardians is the dharmapala (tib chos skyong),

or guardian of the Buddhistdhar m a (law). This type of guardian includes some

of the most prominent protectors in Tibet, such as Mahakala (tib. Gon po) Sri Devi (tib.Palden

Lhamo), Yama(tib Shinhe), Hayagriva(tib. Tagrin), and Yamantaka(tib. Shinje Shed). The Tibetan

dharmapalas are most divergent from other cultures, and perhaps the most

original renditions of imported ideas of guardianship. These deities are oath bound, and

though they are protectors in the fullest sense of the term, they are not constrained

explicitly by position, as the lokpalas and dvarapalas are. Though they are not subject to

a rigid pattern, their positioning follows some dominant themes. A key property of

dharmapalas is their capacity to play the role of guardians of the gate or of direction. For

instance, in the passageway that connects the inner Jokhang to the outer kora, Palden

Lhamo (san. Sri Devi) is a dvarapala, flanking a major threshold between the inner and

outer koras. Another example is the four-foot statue of Mahakala in the Sera Dhaggo

chapel at the rear of the Jokhang, who stands looking fiercely out over the rear

wall of the

temple, posing as a guardian of space as well as of Buddhist doctrine.

Both also demonstrate the complexity associated in thinking about Tibetan

guardians, and it is precisely this complexity that sustains this essay. The

multiple roles

played by dharmapalas alludes to an underlying relationship between all

guardians that

will doggedly follow our account of Tibetan protective deities. I referred

earlier to the

guardian of Tibetan Buddhism as a palimpsest, a document which has been written

on

many times, each message being written on top of others. The difficulty in the

classification of Tibetan guardians signals the existence of these multiple

layers.

Guardian deities seldom succumb to a single paradigm; as we shall see shortly,

they are

perpetually in between.

At the Threshold The house where my mother grew up, in the heart of South India,

was built nearly

a century ago. Its doorframes are made from heavy, solid timbers from forests

that have

long since disappeared in India. As a five year old, the threshold often was as

high as my

knees. I particularly remember tripping almost every time that I entered the

house. I

became convinced that threshold was a strange place, a trial to be overcome in

order to

get inside.

In the Indian view, the threshold is a singular location, in suspension between

inside and outside, as illustrated by the myth of Narasimhan (see VI), the fifth

avatar of

Vishnu. According to the myth, the king Hryanakasyipu meditated for several

years in

order to win the gods favor, and thereby everlasting life. The gods refused to

grant him

immortality; instead, they restricted the conditions on his death. He could not

be killed

inside or outside, during day or night, by man or beast, by weapon or natural

causes, and

so on. On the strength of these boons, Hryanakasyipu became arrogant and

fearlessly

terrorized his subjects. At the intense prayer of a young devotee, Vishnu

returns to earth

in the form of a man-lion, Narasimhan in order to kill the tyrannical king.

Narasimhan

cleverly takes Hryanakasyipu to the threshold at twilight, and kills him with

his nails.

The crux of the story is that Narasimhan is only able evade all the restrictions

on the

circumstances on Hryanakasyipu s death by looking in between the conventions of

night

and day, man and animal, weapon and hand, as well as inside and outside. The

threshold,

the site at which Narasihman kills Hryanakasyipu, is an interstitial place.

The point is that I was right when I was five years old; thereis something

important going on at the threshold. Though this story is Indian, it reflects a

thinking

about the threshold that is consistent in temples across Asia. Any threshold, no

matter

whether in the Jokhang or my grandmother s house, is liminal because it lies in

between

diverse conception of space. As Bernard Faure observes, from a Chinese viewpoint

of

space and place, “The threshold in many local traditions, is a dangerous place,

a focal

point where space inverts…and Turner, among others, has stressed that liminal

states and

individuals are both ambiguous and dangerous.” In Tibet, whose temples and

monasteries are, in part, inspired by both their Indian and Chinese

counterparts, the

threshold is a definitively liminal place. The placement of guardian deities at

the

threshold, then, is indicative of their peripheral status as well as their

ambivalence.

This idea is prevalent throughout the Jokhang. At the front entrance, there is a

set

of sinicized lokpalas painted upon the outer walls, as well as another full set

of four

wooden lokpalas set back in the alcove on either side of the passageway just

inside the

front gate (See Figure 3). Such a redundancy underscores the importance of the

threshold.

Other guardians stand watch over essentially every major threshold in the

Jokhang,

including the previously mentioned Mahakala and Palden Lhamo. The presence of a

ferocious guardian image at the threshold is indicative of a special

consciousness of the

spatial inversions that occur there.

How do we account for the curious juxtaposition of lokpalas, who were originally

guardians of cardinal direction, at the threshold? At the entry to the Jowo

Lhokhang four

lokpalas stand guard over the threshold to the sanctum sanctorum, backed up by two

dvarapalas (See Figure 3). The lokpalas appearance in tandem with the dvarapalas suggests that they

are of similar status. It also indicates that both guardians perform

guardian and applies to guardians as a class. Lokpalas often appear in mandala in their official

capacity, keeping watch over

the cardinal directions. Typically, they appear at the outer rings of the concentric circles

of a mandala. Only in specific wrathful mandalas would one ever see wrathful deities in

the inner ranks. Four, eight guardians, and in some cases an entire legion of wrathful

deities circumscribe mandala (see IX). The placement of lokpalas and protective figures

around mandalas is once again reflective of their liminality in Tibetan conception. Even

mandalas with no visible guardians retain the idea of a protected space. For example, the

symbolic mandalas composed of concentric geometry, a design element is often alludes

to guardians. Common representations include changes in color, or renderings of a

charnel ground.

The relationship between guardians and mandala goes much further. At their

heart, mandalas are protective structures. They makes utter sense as a

fortification; they

are the essence of a layered defense. The traveling camps and the war camps of

Tibet are

arranged in mandalaic patterns. For instance, in Stein s Tibetan Civilization,

it is possible

to glimpse the Dalai Lama s traveling camp (See VII), strikingly reminiscent of

mandala.

The similarity is no coincidence, judging from Stein s account, early Tibetan

camps are:

clearly comprised of concentric enclosures, for we are told of three successive

gateways at a hundred paces distance from on another, guarded by soldiers and

sorcerers or priestswho escorted the visitor. In the center was a great standard

with a high platform….the hierarchies lived at the center…with a throne and a statue of a

protective deity…

This description of a ninth century camp, recorded by the Chinese at the historic signing

of a treaty with the Tibetans, is shot through with mandala. Like all mandala, we see

concentric circles revolving around a clear axis. This description suggests that

mandalas

were practical protective enclosures. They also featured thresholds , gateways

between

successive enclosures, with guardians mediating each gateway. The date (around

822

CE) puts the mandala - camp on the cusp of Buddhism encroachment on Tibet and

invites

speculation about how deeply rooted mandalaic thinking is in Tibet. Regardless

of the

origins of mandalas, there is a direct connection between a military protective

space, and

the spiritual one of mandala.

"A mandala delineates a consecrated superficies and protects it from invasion by

disintegrating forces," wrote the 11th century sage Abhayakaragupta, an Indian scholar

revered by Tibetans. A demarcation between sacred and profane space, order and chaos

is clear throughout mandala iconography. Even the most simplistic renditions of mandala

manifest this concept (see IX). In line drawings of mandala from Tibet and even in

China, there often are circular patterns of lines embedded in more intricate, convoluted

patterns. Beyond the outermost rings of this mandala is a jumble of disordered, undulating lines,

in sharp contrast to the mandala itself, which is comprised of

rigid

geometry. A mandala can be a systematic representation of other elements of

religious

values, including as deities, talismans, animals, symbols, and buildings. A

mandala

integrates these diverse elements into an ordered matrix.

In some representations, the entire spectrum of life can be captured in mandala,

as

it is in thebhavachakr a (see VIII), or the wheel of life . In typical

bhavachakra

mandalas, Yama, the lord of death, is depicted as holding the mandala. Yama’s

position

is symbolic of “the inexorablity of time and process, the inescapability of

cause and

effect.’ Upon closer examination, it seems to me that it is equally likely that

the mandala

is pinning him down. At any rate, Yama, who moonlights as dharmapala, is clearly

on

the outside, in profane space, while the six phases of life are on the inside of

the mandala. In the center, the axis of the mandala is nirvana, liberation from the wheel of life.

The best example of the break between order and disorder that

I saw was in the

three dimensional mandala on display at the museum in the Potala Palace (see

Figure 2,

bottom right). In reality, all mandalas are three dimensional. Given enough

discipline,

an adept practitioner can visualize their true nature. The Potala mandalas,

beautifully

cast in bronze, were extruded into three dimensions for the benefit of common

folk.

Although there were no guardians in sight, one of the mandalas depicted hordes

of

wraiths, ghosts, demons, and other unpleasant creatures dancing on the periphery

of the

mandala. They could not enter; their dark revelry ceased at the boundary of

mandala.

The disc of the mandala marked a disjunction between two distinct conceptions of

space.

Mandalas create a polarity between protected and unprotected space (see Figure

2,

bottom left), between sacred and profane, divine and demonic, order and chaos,

tamed

and wild. It is possible to extend this polarity in several other dimensions,

such as

between heaven and earth, stillness and motion, passive and active, or masculine

and

feminine. The polarity that is set up between mandala and non-mandala space is

central

to understanding the nature of the worlds that guardians stand in between. With

one foot

in mandala space, and one foot outside of mandala, they are truly between

worlds. It is

these worlds that one crosses between when stepping over the threshold.

In most cases, the polarity of mandala is not discrete (see Figure 2). A mandala

is a set of nested concentric layers, and each layer is a progression towards

the center,

which represents one extreme of the polarity. As one moves inward in a mandala,

one

progresses in discrete increments towards sanctity, order, passivity, divinity,

or heaven,

rather like ascending a stepladder. The concept of incremental progression is

the where

guardians become paramount in mandala. Guardian deities stand watch over the

contact

points, the thresholds , between the different levels of mandala. As Ray

comments “the

integration and hierarchical arrangement of [the mandala’s] terrible deities

[indicates] not

only their fundamental importance to the Tantric process of transformation, but

also to

the different stages of awareness bound up within this process." The guardian

deities

directly catalyze the transition between different levels. You must pass through

gates

guarded by them in order to pass to the next level. This is our first glimpse,

then, of the

transformative capacity of guardianship in Tibet. By fiercely attending to

transitional

points, the guardian not only denotes the junction between different levels of

sanctity, but

also facilitates the transition. Guardians change the untamed, disordered world

to the

consecrated space of mandala.

The notion of mandala-space has broad application in Tibet, particularly with

respect to temples. The famous temple of Samye was explicitly erected as a

mandala,

fashioned after Odinpuri temple in Bihar (in Northern India). Samye was built by

the

first major king of Tibet, Trisong Detsen, and has many of the features and axes

of

mandala. In the Tibetan view, Samye “had the symbolic significance of the sacred

circle

(mandala) enclosing the temple palace and the supreme divinity at the core of

the

universe.” The central axis of the mandala, the Utse, contains yet another set

of nested,

concentric layers and is a further extension of the principles of mandala to the

heart of

temple. The construction of the mandala-temple at Samye was a precedent for

subsequent construction of temples throughout Tibet.

All temples are to some extent a mandala: The buddhas and their divine

attendants with their stylized symbolic names were

conceived as coherent units in a kind of divine pattern or mystic circle

(mandala).

This pattern, usually drawn on the ground for the purpose of the rite, served as

a

means toward psychological reintegration of a suitably instructed pupil, who

received consecration from his master in the actual center of the diagram. In

some cases, temples were built asmandalas, thus serving as permanent places of

consecration.

The organization of the Jokhang is very similar to the rendering of a cosmos as

appropriated by a mandala. In both structures, there are ‘layers’, and a central

figure or

axis. In the case of the Jokhang, the central axis is the deity Jowo, around

whom the

entire temple revolves. Pilgrims in their circumambulation around the periphery

during a

kora are quite literally in orbit around the center of the world.

An examination of the floorplans of temples all over Tibet makes it apparent

that

there is a close connection between mandala and temple. Both entail ordered,

nested

layers of consecrated space, both are sacred demarcations from the world around

them.

This symmetry between temple and mandala is clearly derived from a unified

concept of

cosmos appropriated both in the construction of temples and in the crafting of

mandala.

Most important to our discussion is the presence of guardians at transitional

points of

both mandalas and temples.

I experienced these ideas first hand at the magnificent Gyantse Kumbum (see X),

located a day s journey south of Lhasa. This structure is at oncechor ten,

temple, and

mandala. From the nearby Gyantze Dzong (fort), from where you can look down on

the

temple and the entire valley, the Kumbum looks much like a squat chorten. At the

same

time, the roofline of the Kumbum has the nested geometric architecture of

mandala: if it

were somehow ‘flattened’, a mandalesque pattern would result. It is also clearly

a

temple, chock full of deities and altars. A visit to the Kumbum is in every

sense a

journey that engages mandalaic polarities. As you moveinwar d, or closer to

central axis,

you moveupwar d as well. There are drastic changes in the demeanor of the

deities as

you ascend. Guardians stand watch over the lower levels in hordes, while other

deities

are enshrined at the higher levels. As in mandala, the guardians are peripheral,

standing

watch over the levels closest to the profane, disordered worlds outside. As you

wind up

through the stairways of the Kumbum, in transit between discrete layers,

guardians again

make their ferocious appearance. Such stairways are transitional points between

discrete

levels of sanctity. The stairways are as interstitial as the threshold of

temples, and require

guardians to facilitate the transformation from one level to another.

Protective deities commonly appear at a few other special locations, such as on

the outer walls of a temple or monastery, or in the gonkhang. Typically, the

gonkhang

chapels are small dark, and otherworldly, tucked in one corner of an outer kora.

Set back

from the rest of the monastery, the atmosphere of the gonkhang is distinct from

the rest of

the temple. They are filled with a different lighting, a different paint scheme

(I noticed

walls of red or black), and a distinctly wrathful subset of deities. There are

also special

restrictions on who can enter. The gonkhang is in a world of its own. There is a

parallel

between the threshold and the gonkhang, both are set apart from the rest of

temple, both

are liminal, and both are the realm of guardian deities. Though the gonkhang is

not

located at an explicit spatial transition, it is located in the periphery. As we

shall see in

our later discussion, it has its own transformative function.

The positioning of guardian deities reflects the greater polarity of mandala

from

profane to sacred, from active to passive, wrathful to compassionate. Guardians

are

undoubtedly profane. They have demonic roots, and come equipped with unsavory

features such as freshly severed heads, corpses, and a horde of attendant

demons.

Furthermore, a defining feature of the guardian image is motion. The long, bold

diagonals

that cross guardian images and sculptures facilitates the impression of motion.

Most

guardian deities are captured in mid-stride, as if the guardian is in the

process of dancing.

Several other cues connote motion. The grain of a guardian s hair is swept back

and

away, almost as if thrown back by the fury of their dance. The ornate flames

that rage

behind the guardian seem to be reacting to the energy of the dancing deity,

flaring in

opposition to step of the dance. The fiery scrollwork and inlays that surround

them are

perhaps a reference to their wild and chaotic origins. Though the fire or cloud

scrollwork

behind them is highly ordered, I suggest that it is meant to leave the viewer

with a feeling

of disorder. Another feature that has a disorienting effect is the long,

undulating sash that

appears (typically in green) around many guardians. Its flowing line, while

fairly

constant between guardians, also alludes to chaos. If a temple is a mandala, it

makes

sense that guardians who are active, demonic, wrathful, and profane creatures,

remain on

the periphery.

In contrast, towards the center of a temple, one is more likely to find calm,

peaceful imagery, figures that are passive, ordered, subdued, and divine. The

significance of motion can only be seen in contrast to other members of the

Buddhist

pantheon, most of them sitting peacefully, hands resting in comfortable mudras.

Others

may be standing, or have a cocked head. Major deities, such as Padmasabhava,

Buddha,

or Tsongkhapa are subdued when compared to the guardian image, which is alive

with

consummate energy. Even the Dunhuang guardians are at best posturing; they

seldom

have the motion that characterizes Tibetan guardians.

The motion that is present in the guardian image suggests that they are active

deities; indeed, they create sacred space. Without the presence of guardians, a

consecrated space either in mandala or in temple cannot exist. Their very

presence

converts an ordinary space into a sacred one. As in mandala, they need not be

explicitly

present. Upon the many doorways and thresholds of Tibet, I saw myriad charms,

decorations, and ornamentation that invoked guardians. The presence of such

deities at

the threshold indicated a cognizance of the liminality of the threshold, and the

transition

that occurred there. These protective designs included a mandala upon the

doorway, a

yak skull, or simply wrathful faces on the doorways (see XI, XII). Each home is

a

protected, sacred space, distinct from the profane world outside. Without

guardian

deities or markings that refer to them, there would be no difference between the

two

worlds. These ideas are intimately related both to the Indian conception of

threshold, as

well as to the Taoist kings (see XIII) who appear in tandem upon posters

throughout Han

China.

Excepting the gonkhang, the placement of guardian deities is consistent with

ideas

of space in India and China. Consequently, we are left with a mystery: though

Tibetan

guardians appear in roughly the same marginal places as their counterparts at

Dunhuang,

and throughout India and China, they are iconographically distinct. How do we

account

for the divergent guardian image in Tibet?

One approach to this question is from a materialist viewpoint. In Tibet, perched

at 10,000 feet, life is difficult, particularly if you are a nomad, at the mercy

of the weather

and the seasons. On the vast high plains, unfurling above 15,000 feet, resources

upon

which to live are scarce, to say nothing of desolation of western Tibet or high

mountains.

Though Tibetan culture has beautifully evolved to thrive in its surroundings, a

materialist

might put together a story about how the perils of the Tibetan environment

engendered a

‘protective impulse’. This impulse, perhaps tucked deep in human psyche, is

ultimately

codified in Tibetan religion. To understand guardians, we might take a page from

an

early field anthropologist, Bronislaw Malinowski, who accounted for the

ritualistic magic

of the Trobriand Islanders by looking to the unexplained:

There is first the well known set of conditions....On the other hand, there is

the

domain of the unaccountable and adverse influences , as well as the great

unlearned increment of fortunate coincidence. The first conditions are coped

with

by knowledge and work, the second by magic.

According to Malinowski, the islanders dealt with forces over which they had no

control,

such as the weather, by magic. Applying this logic, the Tibetans might confront

the harsh

reality of the landscape, the severe winters, roving bandits, and the

uncertainties of living

at high altitude by inventing guardian deities as protectors to tame the

landscape. In

such a model, the mythical weaponry, the wrathful countenance, and other aspects

of the

guardians are responses to Malinowski s unaccountable and adverse influences .

As a

kind of control, one might look to the caves of Dunhuang in China’s Gansu

province,

which contain many guardians that are explicit likenesses of military figures

(see XIV),

complete with armor, real weapons, and militaristic expressions. Though set in

the

desert, Dunhaung is a fertile oasis with trade routes that have flourished for

thousands of

years, and its landscape poses few threats. On other hand, its position at a

vital

crossroads made it a ripe target for millennia of marauding barbarians, bandits,

and a

strategic prize for imperial armies. The military is the entity that the

citizens of Dunhuang

turned to for protection; consequently, it is not surprising that guardians of

Dunhuang

lokpalas and dvarapalas look like soldiers and generals. The differences in

physical and

historical context may in part account for diverse manifestations of the same

office of guardian in Tibet and in Dunhuang. Nonetheless, I believe that

applying materialistic thinking to the guardians of Tibet only accesses a small

part of their story, the first layer upon our palimpsest of guardianship. The

Tibetan rendition of guardian deities goes farther than a simple response to

factors beyond Tibetan control. To visualize these underlying layers of guardianship, we must look

deeper at the Jokhang, not in space, but in time. Throughout this essay, I have alluded to many

iconographic elements that are part

of the iconography of transformation. These include the activity and motion that

are part

of the guardian image as well as the wrathful visage of guardians. Many of these

features, help establish the link between guardians and temple patrons by

drawing the

viewer in. The long diagonals, brilliant color, and nested scrollwork are

examples of this

telescoping effect that captures the attention of the temple patron.

The eyes of guardian deities and protectors who are not located at the threshold

often are not directed at temple patrons. Instead, they are looking down and

away, fixed

on the task at hand, which is most often their impassioned dance on the back of

some

hapless victim. This image is still directed at the temple patron. We as temple

goers are

witnesses to the transformative, or subjugative, power of the guardian image.

This

connection between the guardian image can be modulated in the gonkhang, where a

thin

sheet can veil the guardian statues, shielding the eyes of the pilgrims. In this

situation,

the horror of the guardian deities is only magnified by the imagination of the

pilgrim.

The veil that hides guardians at the gonkhang suggests that the mechanism of

transformation that is operative on the temple patron is fear. Though many

Tibetans do

not directly admit that they are scared of the protectors that proliferate

Tibet, it is difficult

to imagine these images, which contain dead creatures torn limb from limb,

bristling

teeth and mystical weapons, as placid. Imagine the reaction of children,

uninitiated in

culture and the society of religion, to Tibetan guardians -- their reaction

cannot be

anything but fear. The guardians send almost universal messages of ferocity and

wrath,

despite the philosophical protestations of the monks that I have talked to.

However, those

who are sacred and pure have nothing to fear, and therefore need not be scared

of the

wrathful deities. To those who follow Buddhist dharma, the guardians are welcome

friends. It is as if the guardians, with their penetrating eyes, are asking each

viewer a

difficult question: "What are you hiding that you should be afraid of me?" The

wrathful

gaze of the guardian then, is the analog of yaksa s riddle. It is the guardian s

way of

testing the temple patron.

This interface between human and deity is at the crux of understanding the

wrathfulness that manifests itself in Tibetan guardians. I believe that the

connective

faculty of the guardian image stands apart from most of Tibetan religious art.

As

mentioned before, central deities are often larger than life, and look off into

space. Their

attention is not directed at the temple patron. Their purpose is to establish a

sense of awe.

Another genre of Tibetan art depicts a process, a story, or an event. Other

images, such

as of Tsongkhapa or Padmasabhava, do establish connections with the viewer, but

on a

more serene level. Their gaze conveys peace and compassion. Still, I contend

that

guardian images are particularly designed to connect with the temple patron on

two

further counts. First, guardians are more mundane than most deities, and remain

uniquely

accessible to the general Tibetan populace. Additionally, because they are more

mundane, they are placed on the periphery, and become the first deities the

temple goer

sees.

The logic of syncretism comes into focus. As I pointed out in the last section

guardian deities lend themselves to change because they are on the periphery,

and are

easily modified without affecting the core of a religion. However, if a religion

seeks to

remain connected with its people, it makes beautiful sense to put indigenous

elements on

the periphery because these are the deities who are familiar to the local

populace. With a

foot in both worlds of sacred and mundane (or profane), guardians are a bridge

to the local populace. Their position on the front lines of Buddhism is not to

be underestimated. The guardian deity’s purpose is to ‘remove obstacles’ to

Buddhism. The primary

traffic through the threshold is not the forces of nature, or hordes of local

gods. It is

simply a stream of temple goers. The enemies of the Buddha come packaged in the

hearts and minds of the temple pilgrims. These mundane, impure elements in

temple

patrons constitute the primary threat to Buddhism, and it is against the profane

forces

within each person that the guardian’s energy and ferocity are directed. If

these impure

elements are the vestiges of indigenous Tibetan tradition, guardians ease the

transition

from this religion to Buddhism. The obstacles to Buddhism might also impious

thoughts

and feelings, as well as ignorance. As pilgrims cross the threshold and survive

the gaze

of the guardians, they enter the temple changed for the better.

Thus nature of the transformation is symmetric with other transformations that

permeate guardianship in Tibet. In what has to be seen as a compassionate

gesture, the

pilgrims who enter the temple are not repelled, rather, they are allowed egress,

albeit

transformed. The many levels of transformations that are localized at the

guardian deity

all have one, common output via the connection with the temple patron. The

temple

patrons are transformed along the exact axes of mandala: from profane to sacred,

impure

to pure, passive to active, motion to stillness, feminine to masculine,

indigenous tradition

to Buddhist.

Transformation is the central thesis of Marilyn Rhies book, Worlds of

Transformation. She argues, through a series of beautiful images, that Tibetan

culture places great emphasis on personal evolution: …during the last few

centuries, any Tibetan, even the unwashed, vicious bandit chief galloping around

in the mountains from victim to victim, could turn in his saddle and see a giant buddha carved on a

cliff...and be reminded of his own evolutionary potential and the help everywhere available to him

for achieving this.

The metaphors for evolution and journey have seeped through many aspects of

Tibetan

culture. Both mandala and temple are spatial representations of a reality that

progresses ,

and the pilgrimage as a journey and an evolution is an important motif in Tibet.

If we

accept Rhies argument, then guardian deities take on an entirely new

psychological

value. They stand watch over the difficult parts of the journey, over the

threshold

between stages, at transitional points. Thinking back to the Gyantse Kumbum, the

concept of a journey becomes a beautiful metaphor for enlightenment. If

transformation

is a driving force in Tibet, the prevalence of guardian deities makes sense.

It is eminently possible that my own Westernized viewpoint has led me astray.

To think of the guardian as menacing is a categorical mistake, my Tibetan

friends might

say, in part because their wrathful energy is not directed against Tibetan

people, but the

enemies to Buddhism. In this sense, they are friendly spirits who manifest

wrathful

energy. Once again, perhaps the Tibetans view guardian deities like the owner of

the

dangerous Doberman might view his dog; a powerful, but essentially faithful

companion.

Still, I consider the problem of the perspective of their guardian images rather

intractable.

It is a problem that has persisted in generations of scholars, and one that I

cannot avoid. I

can only see the guardians from my own context and go from there.

Even in Tibet, the opinion that one has of the guardian image is, like anything

else, contingent on history, perspective and position. In my discussions with

contemporary Tibetan monks, some of Western origin, I found that many of them

cast

the wrathful energy of dharmapalas and dvarapalas as philosophical devices,

expressing

compassion through their wrathful energy. While such an interpretation might be

valid in

from a monastic standpoint, it is probably divergent from a nomad s view of the

guardian

image, or even a westerner that writes about them. Still, from each of these

vantage

points, I believe that the guardian image manifests transformation, whether it

is from

ignorance to enlightenment, from profane to sacred, or from demonic to divine.

Pehar:Major Gelug protector and Yidam. Originally was the guardian of Samye.

Princess Wencheng: The second wife of Songsten Gampo, and one of the major

players in the demoness subduing temple myth. Also known as Kong Jo in Tibetan.

Samye: A monastery built in the shape of mandala, after Odinpuri temple in

Bihar. Siva:Major Indian god is the destroyer, or transformer. The iconography

of Siva is important for thinking about guardian deities. Songtsen Gampo: Major

ninth century king of Tibet. His rule saw the maximum extent of Tibetan

influence in Central Asia. He presided over the Great Debate, and was

responsible for building the Jokhang Srin Mo: The name of a demoness is fabled

to have inhabited Tibet. The features of the demoness are deeply symbolic,

including ties to chthonic / telluric roots. Stupas:A Buddhist funerary or

commemorative mound. The architectural precursor for many extant Buddhist

architectural motifs, such aschor tens and temples. Terma:One of the oldest

lineages of Tibetan Buddhism Thankgas:Embroidered paintings of religious value,

typically depicting deities or important personages. Trandruk Monastery: One of

the demoness subduing temples located in the Yarlung Valley, built at the same

time as the Jokhang. Tsongkhapa:Also known as Je Rinpoche, a seminal teacher in

Tibetan Buddhism.

Vaisravana: Guardian of the north, king of the yaksas, and the god of wealth.

Vaikuntha:Heavenly abode of Vishnu.

Vajrapani:Boddhisatva, known for his Powerful Thunderbolt". He also appears as

a

protector, appearing in a characteristic blue and holding a thunderbolt.

Tib:Channan Dorje Vishnu:Major Hindu god who has many incarnations on earth.

Yaksas:A curious tutelary deity with ties to fertility and trees. These spirits

also were the iconographic basis for later Buddhist and Hindu art, including the

guardian image. Yarlung Valley: The cradle of Tibetan civilization, and the location of

some of her oldest structures. It is located about three hundred kilometers to the

southwest of Lhasa. Yumbulungang: The first castle of Tibet, located in the Yarlung Valley.

Yama:The Hindu god of death, who has been ported to Tibet as a demon and guardian.

Tib:Shinhe Yidam: Major tutelary deities in Tibetan Buddhism, such as Pehar. Often have a

wrathful iconography. Works Referenced Bonavia, Judy.The Silk Road. Lincolnwood, Il:

Passport Books, 1995. Booz, Elizabeth. Tibet: Roof of the World. New York, NY: Passport Books,

1994. Bernet-Kemper, AJ.Ancient Indonesian Art. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1959

Tryngpa, Chogram.Orderly Chaos: The Mandala Principle. Boston, MA: Shambala, 1991.

Chandra, Lokesh.Buddhist Iconography. New Delhi : Aditya Prakashan,1988. Chandra, Lokesh.Tibetan

Mandalas. New Dehli, India: Aditya Prakashan, 1995. Chan, Victor. Tibet Handbook Chico, Calif. :

Moon Publications, 1994. Conze, Edward.A Short History of Buddhism. London, England: Unwin 1981.

Corless, Roger. The Vision of Buddhism. New York, NY: Paragon House Publishers, 1989. Desai,

Vishakha N. and Mason, Darielle, Gods, guardians, and lovers : temple sculptures from North India.

New York, NY : Mapin Publishing, University of Washington Press, 1993. Dreyfus, George. The

Shuk-Den Affair: The Origins of a Controvery. Available at

http://www.tibet.com/dholgyal/shugden-origins.html. Dowman, Keith. The Divine Madman. London, UK:

Rider and Co., 1980.

Dunham, V. Carroll.Tibet : Reflections From the Wheel of Life. New York NY: Abbeville Press

Publishers, 1993. Evantz - Wentz, W.Y.The Tibetan Book of the Dead. Oxford, UK: Oxford

University Press, 1974. Faure, Bernard. "Space and Place in Chinese Religious Traditions". In

History of Religions. University of Chicago Press. May 27, 1987. Getty, Alice.The Gods of

Northern Buddhism; their History, Iconography and Progressive Evolution through the Northern

Buddhist Countries. Rutland, VT: C. E. Tuttle Co, 1962 Goswami, Niranjan. A study of the

Ugra-Murtis of Siva. PhD. Dissertation, University of Pennsylvaina, 1972. 99-100

Gyatso, Janet. "Down With the Demoness: Reflections on a Feminine Ground in Tibet". In Feminine

Ground; Essays on Women and Tibet. Ed by Janice D. Willis. Ithaca, NY: Snow Lion Publications,

1989. Hallade, Madeleine.Gandharan Art of North India and the Graeco-Buddhist tradition in

India, Persia, and Central Asia.New York, NY: H.N.Abrams, 1968. Harvey, B. Peter.An Introduction

to Buddhism : Teachings, History, and Practices. New York, NY: Cambridge University

Press, 1990 Heidegger, Martin. Poetry, Language, Thought. Trans. Albert Hofstadter New York, NY:

Harper Row, 1975. Lansing, Stephen. Priests and Programmers: Technologies of Power in the

Engineered Landscape of Bali.Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1991. Linrothe,

Robert. Ruthless

Compassion: Wrathful Deities in early Indo-Tibetan Esoteric Buddhist Art.London

Serindia Publications, 1999. Lopez, Donald.Buddhism in Practice. Princeton,

N.J. : Princeton University Press, 1995. Lopez, Donald.Religions of Tibet in

Practice. Princeton, N.J. : Princeton University Press, c1997. Madsen, William.

"Religious Syncretism". In Handbook of Middle American Indians, vol. 6 Austin,

TX: University of Texas Press, 1987. Marshall, John Hubert, Sir,The Buddhist Art

of Gandhara : The Story of the Early School, its Birth, Growth, and Decline. New Delhi, India :

Oriental Books Reprint Corp., 1980. Murthy, Krishna.Iconography

of Buddhist Deity Heruka. New Delhi, India: Sundeep Prakashan, 1988. de

Nebesky-Wojkowitz, ReneOracles and Demons of Tibet: The Cult and Iconography of

Tibetan Protective Deities. Gravenhange: Mouton, 1956. Pal, Pratapaditya.On the

Path To Void : Buddhist Art of the Tibetan Realm. Mumbai, India: Marg

Publications, 1996. Ray, Reginald A.Mandala Symbolism in Tantric Buddhism. PhD

Dissertation, University of Chicago, 1973. Rhies, Marylin M.Wisdom and

compassion : the sacred art of Tibet New York, NY: Abrams, 1991. Rhies, Marilyn.

Worlds in Transformation: Tibetan Art of Wisdom and Compassion. New York : Tibet House in

association with the Shelley and Donald Rubin Foundation : Distributed

by Harry N. Abrams, 1999. Ricard, Robert.The Spiritual Conquest of Mexico.

Trans. by Lesley Simpson. Berkeley, CA:University of California Press, 1966.

Snellgrove, David and Richardson, Hugh.A Cultural History of Tibet. New York, F.

A. Praeger, 1968. Stein, Rolf. "The Guardians of the Gate." FromMythologies, ed. Yves Bonnefoy.

Chicago, Il: University of Chicago Press, 1991. Pg 896-910.

Taylor, Chris. The Lonely Planet Guide to Tibet. Hawthorn, Australia: Lonely

Planet Publications 1995. Tucci, Giuseppe.The Theory and Practice of the

Mandala. trans. Alan Houghton Brodrick. London: Rider, & Co, 1961. Whitfield

Roderick.Dunhuang, Caves of the Singing Sands : Buddhist art from the Silk Road.

London, England: Textile & Art Pubs., 1995 Walshe, Maurice O C.Pathways of Buddhist Thought: Essays

from The Wheel. New York NY: Barnes & Noble, 1971. Van Bemmel, Helena.Dvarapalas in Indonesia :

Temple Guardians and Acculturation. Rotterdam Brookfield, VT : Balkema, 1994. Van Oort, H. A..The

Iconography of Chinese Buddhism in Traditional China. London, England: E.J. Brill, 1986 Volkmann,

Rosemarie. "The Genetrix/Progentress as the Exponent of the Underworld." in .Female Stereotypes

in Religious Traditions. ed. By Ria Kloppenborg and Wouter J. Hanegraaff. Leiden, NY: E.J.

Brill, 1995. Credits This

essay would not have happened without the kindness and help of many people. Below are a few of the

people who have major contributions to this project. Advisors: Bernard Faure, Professor,

Religious Studies Mark Mancall, Professor, History Essay Feedback and Project Development:

Hilton Obenzinger, Writing and Critical Thinking Ardel Thomas, Writing and Critical Thinking

Program Director:

Monica Moore, Interdisciplinary Program in the Humanities Paul Robinson, Director,

Interdisciplinary Program in the Humanities Traveling Partners: James Russell, sophomore in Civil

and Environmental Engineering

Liu Zhijun, doctoral student, South-Central Institute of Nationalities, (Wuhan, China).

Translation and Lhasa Support: Qiong Da, postgraduate student, Central Institute