The Hemis Festival

Introduction

The Hemis monastery was established in 1672 AD by the then king Senge Nampar Gyalva. Hemis monastery lies in the foothills on the southside of the Indus approximately at a distance of 42 km from Leh, and is reached by a motorable road. Crossing the river at a cantilever bridge, the road skirts up towards the village of Chushod. Then it passes over to a green oasis in the middle of rugged mountains and high altitude desert plains, lined with poplar and willow trees. As one nears the adjoining hills, the Hemis gompa, comes in view. Across the stillness of the wide expanse, the Hemis gompa stands upright built in Tibetan style, jutting out of the mountain top.

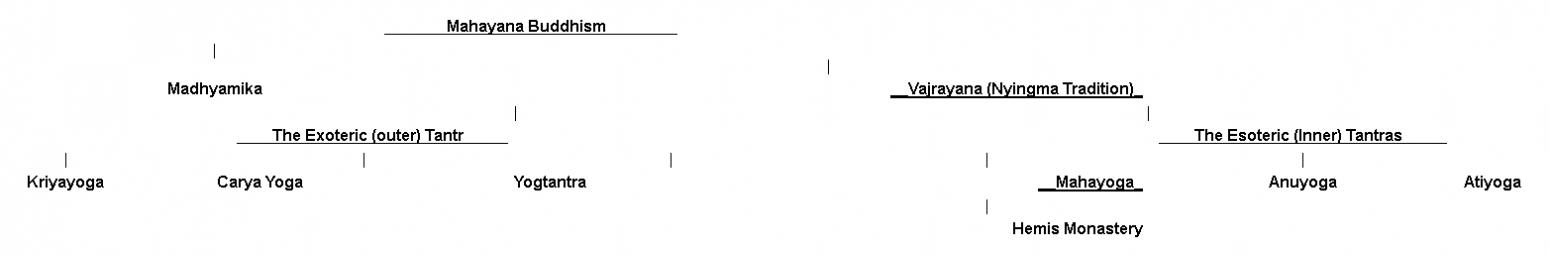

The Hemis monastery traces its intellectual lineage to the nyingma or the ancient tradition of the vajrayana school of Tantric Buddhism. The Tibetan nyingma tradition is divided into several sects : The kargyu founded by Marpa (1012), sakya, founded by Khon Kon Chang Yal Po (1034-1102), and gelug, founded by Je Tsong Kha Pa (1357-1419). The Hemis monastery finds place in the drukpa - kargyu tradition. Their authoritative texts are the Mahayoga Tantras which expound the teachings of the esoteric inner Tantras as opposed to the exoteric ones. These works have a different flavour from the sutra texts of early Buddhism. Buddhist works after the 11th Century are known as the New Tradition. The Vajrayana expounds a Tradition of Empowerment, wherein the goal of enlightenment is reached in a short period of time. The outer and the inner Tantras though one in their goal, differ in the means of spiritual enlightenment. The practices at the Hemis monastery are a direct lineal descent of the teachings expounded in the Mahayoga Tantra school, or the esoteric school of Vajrayana.

Space and Setting

The Hemis festival takes place in the rectangular courtyard in front of the main door of the monastery. The space is wide and open save two raised square platforms, three feet high with a sacred pole in the centre. The platforms mark out the centre of the performance space, in front of the main door to the monastery. A raised dias with a richly cushioned seat with a finely painted small Tibetan table is placed with the ceremonial items - cups full of holy water, uncooked rice, tormas made of dough and butter and incence sticks. A number of musicians play the traditional music with four pairs of cymbals, large-pan drums, small trumpets and large size wind instruments. Next to them, a small space is assigned for the lamas to sit.

Time, Date and Objective

According to the Tibetan calendar, the great annual festivals held in the villages of Ladakh takes place in winter, with the exception of thseshu held at Hemis in summer. This is one of the most important events of the valley, its chief feature being the presentation of a mask dance-drama for two days at a stretch. From the time of Rgyalsras Rinpoche around the year 1730, the Hemis Festival has been observed year after year without break and has now become well known the world over. The festival commemorates the birthday of Guru Padmasambhava, the celebrated founder of the Lama tradition and the presiding authority of Tibetan Buddhism. According to the records in Sikkim, Padmasambhava came northward and convinced the Lamas of Tibet that he was sent to Tibet as an incarnation of Buddha. The festival both eulogises the great deeds of Padmasambhava and reiterates the victory over evil for the protection of Buddha dharma. Guru Padmasambhava is the founder of the Tibetan tradition and the source of the Terma tradition of the nyingma. He is popularly known as Rinpoche, the precious teacher. Nyingmas honour him next to Buddha and refer to him as the second Buddha. It is believed that guru Padmasambhava descends as a representative incarnate of all the Buddhas, to bestow grace and improve the conditions of living. He does so on the 10th day of each month and all of the 10th dates which come in a year or the most important of the 10th of the Monkey year in a cycle where the thangka of the guru is exhibited. Each year, the Hemis Festival is observed. The purpose of this sacred performance and the dances is to bestow good health, subjugate disease and conquer evil spirits. Guru Padmasambhava is regarded as one of the most extraordinary teachers in the history of Buddhist sages, a possessor of enlightened power. He was a great esoteric practitioner, said to have been born in a lotus, led an ascetic life and taught numerous followers about the esoteric approach to enlightenment and had the distinction of assuming different forms at different places.

Introduction to Chams Performance

The Mask Dances of Ladakh are referred collectively as chams Performance. Chams performance is essentially a part of Tantric tradition, performed only in those gompas which follow the Tantric vajrayana teachings and the monks perform tantric worship. The chams are performed in strict adherence to the prescribed texts orally transmitted, from generation to generation. Chams are performed with masks, and costumes of various meditative and protective deities. Each monk assumes the personage and personality of the deity he is meant to characterize. They then come out into the open courtyard and dance around the central pole with slow and solemn movements of legs and hands to the special music of drums, cymbals and wind-instruments. Tibetan ritual music played during chams performance contains a variety of protean forms. Tibetans believe that religious music has its origin in the teachings of the dakinis. Legend also holds that a lama named Takpo Dorjechang (1543-1588), transmitted the most complex and beautiful music the yang (olbyangs) through dakinis. Within the ritual context, the main function of music as described by Chogyam Trungpa Rinpochey, is to act as an accompaniment to the general psychological process of the rite. Music is looked upon as a sacred offering to the deities. Aurally beautiful, it enhances the dance-drama by sustaining and lending the whole performance an orderly rhythmic element. The music that is played in monasteries is often categorized in terms of the deity to whom the offerings are made. The musical offerings are often suited to express the nature of the deity.

Tsamchot Dance: Dance of The Black Hat (Janaka) Dancers

After the preliminary preparations, the show gains momentum. Thirteen dancers with large black hats with wide round rims enter the scene. From the back of these hats coloured ribbons stream down. Their robes are heavy and made of rich Chinese silk with brocade. They wear rich capes and aprons and a necklace with a skull emblem, which is a potent symbol to remind the viewers of the impermanence and brevity of life. They slowly dance their way round the courtyard, clock wise. Each dancer is given a few sprigs of dried sacred herb by a lama, and then they slowly make their way to the exit. The purpose of this tantric dance is to dispel evil forces and mark out the exterior limits of the performance space and ‘bind’ the quaters by their sacred movements. The number thirteen is identified with the thirteen yugas of the Cosmos and thirteen rings of the chorten.

Dance of The Sixteen Serbak / Zangbak : Compassionate Dakinis

Sixteen males dressed as compassionate dakinis with metal masks enter the arena of the performance. Each of these dakinis hold a damaru and a bell in their hands. They dance in slow steps around the sacred pole to the chant of cymbals and drums chanting in a low melodious voice the mantra of Padmasambhava : Om Vajra Guru Padma Siddhi Hum.

They chant the mantra four times and offer their benediction. Their task is to purify the sacred space, the objects of worship, the lineage of teachers, as well as the disciples.

Dance Honouring the Eight Aspects of Padmasambhava

This is the most spectacular aspect of the whole performance, infact, the centre-point of the ritual dance. The great guru Padmasambhava, in whose honour the festival is performed makes a dramatic entry with his entourage. The guru Padmasambhava wears a golden mask with benign countenance, and a serene Buddha like face found so often in the sculpture of South East Asia. The guru is led by a procession of musicians, some masked and otherwise, to the resounding sounds of music : two lamas hold incense pots (phoks) and two blow wind-pipes (rgya gling), two play long trumpets (dugchen). They enter the arena in rows. Then follows guru Padmasambhava accompanied by a disciple who carries a parasol for the guru. Padmasambhava is accompanied by his seven more personifications. It is interesting to observe that the bodily size of Padmasambhava is nearly one and a half times more than his other incarnations. Their details are given in the chart below :

Eight Aspects of Guru Padmasambhava

| Name | Colour of Mask | Attributes in hand | Aspects |

| 1. Padmavajra | Gold | Bell & Skull | Preached Dakinis |

| 2. Padmasambhava | Blue | Vajra & Skull | Moved the wheel Dharma and subjugated evil |

| 3. Lolden Mchhog | Flesh-coloured | Damru & Incense | A Great teacher |

| 4. Padmar Gyalpo | Flesh-coloured | Damru & Incense | A Great teacher |

| 5. Niyama Odzer | Yellow | Sun symbol & Trident | Showed miracles |

| 6. Shakiya Singe | Yellow | Bowl & Meditational Mudra | Received teaching of Mahayoga Tantra |

| 6. Senge Dadoks | Blue-Black | Vajra & Scorpian Mudra | Destruction of heretics & their conversion |

| 7. Dorje Tolod | Reddish-brown | Vajra & Iron | Subjugated all the evil spirits of Nepal, Tibet and Bhutan. Revealed the truth for the people. |

The layout of the Performance Space. 1 & 2 Central altar with flagstaff, 3. Dais for head lama, 4. Seats of the musicians and other lamas, 5. Space for the sponsors, 6. Space where the eight aspects of Padmasambhava receive worship, 7. Space where 16 forms of katichan or dakinis sit during the worship of Padmasambhava. All the characters take their respective place in the courtyard (indicated in the diagram).

The four masked heroes praise the qualities of body, speech and mind of Padmasambhava and dance before him. Then the five heroines, who represent the five skandhas, the five senses, the five elements, the universe of five Buddhist categories, dance in front of Padmasambhava and praise the three bodies of the guru. Then each of the incarnations of Padmasambhava wearing masks of different colours, dance one after another and display their majesty and prowess to protect and bless humankind by articulating their qualities by their gestures. A group of sixteen dakinis pay homage to the guru for his kindness and compassion for humankind. They praise him for descending on earth by riding the rays of the sun. They recall his deeds and entreat him to come again in the future.

The Dance of The Protectors of Dharma

After the guru Padmasambhava is propitiated the second most important part of the performance takes place. Concerned mainly with the protection of Buddha dharma and banishment of evil, so that Dharma retains its unshakable strength at the face of destructive forces and obstacles that lie in its path. Twelve Dharmapalas who are especially assigned the task to protect the teachings of Buddha now emerge wearing their colourful masks, and holding their respective weapons. They dance in ecstasy to protect the teachings of Buddha.

Dance of Turdag: Masters of the Graveyard

Four dancers emerge wearing white masks representing graveyard ghouls with sunken cheeks, gaping mouths and protruding fanged teeth. They are the masters of the graveyard. Their task is to locate evil and carry those evil and demonic entities to higher deities who have the power to destroy them. Their bodies are covered with white cloth on which skulls and ribs are depicted by red streaks.

Dance of The Four Protectors of Dharma

Four figures with ogre-type masked faces with a third eye on their foreheads appear. Their mouths are open with a protruding tongue curled upwards. Each holds a weapon with which the demonic and evil forces can be combatted. They dance for nearly ten minutes, then symbolically cover the object of their weapons. The evil spirits who pose a threat to dharma are caught by the ‘hook’, tied with the ‘rope’, rolled with the ‘iron chain’ and paralysed by the resounding sound of the bell.

Dance of The Herukas

Another procession of dancers come down the steps. They are the four herukas or the wrathful forms of Buddha. These forms of Buddha dance and put an end to evil. They transform the negative traits of the psyche into pure nectar of enlightenment.

Dance of Tsoglen Na, Who Puts an End to Evil

Five dancer-deities enter with grotesque masks, in red, white, yellow, green and brown. One among them who leads, wears a big devil mask, with curled tongue and tusks. Monks enter and hold out the offering, which is sprinkled, the remainder is placed by the uncovered effigy made of dough. The leader with a demon - mask, approaches the effigy and cuts it into two. This signifies the ultimate death of the evil spirit. The monks remove the remnants of the figure. In the final episode of the performance, five heroes, (saking) who belong to the earth and five from the heavens (namking), appear with masks amid the drum beats, demonstrating their triumph at the destruction of the enemy. The common people of Ladakh refer to them as the heroes of the sky and earth. In the final act, the thangka of the guru is rolled back to the resonance of the music.

The next day the first act of devotion consists of preparation of the high altar and the seat for the incarnate lama. Seven cups full of water, grains and butter tarmas are kept in position. The ceremony begins by unrolling the thangka of silk patch-work of the great Lama Rgyalsras Mipham Rinpoche, the great teacher and guru who established this monastery. Thangka is unrolled to the music played by lamas with yellow robes and red hats, who stand in a row in front of the small altar. Thirteen, dancers enter the performance arena. They are led by lamas playing instruments and two hatuks, who play the role of police-jesters. The dancers carry dried barley sprigs. And as they go out they throw the sprigs all around. Then a young lama walks in with an incense pan and fumigates the place of performance. After the dance, the stage is cleared. The focus of worship shifts inside into the prayer hall to offer worship to the deities who protect the land of Ladhak.

Worship of Rgyalpo Pehar: The Protector Deity

The monks assemble in the hall and ‘recreate’ the altar of Rgyalpo Pehar, the protectress of Hemis monastery. The Rgyaplo’s body is decorated with textiles, silk cloth, flags, streamers, ornaments and various weapons. Thangkas of Avalokets Vara goddess Tara, the sages and Padmasambhava are displayed. A long wooden altar with fine carvings is constructed and various offerings are placed in a row. A skull cup containing chang, drink made with fermented barley, is placed in the centre with cups full of water. On the right side of the altar, rows of lamas sit on the floor unrolling their manuscripts, while opposite them a raised altar is placed where the young incarnate lama witnesses the ceremony. Rgyalpo Pehar is the Tibetan form of goddess Kali, the protectress deity of the monastery. This worship is performed solely for protection of the monastery, the people, the land, the animals and the ecology of the area. The worship goes on for one hour till Rgyalpo Pehar is propitiated and satiated.

Dance of Maha Dongchen: The Bison/Buffalow Masked Deity

The Maha Dongchen, with a Bison faced Mask, and his entourage come and dance in a group, encircling the flag-staff. Two monks inscribe a triangle-mandala in blue with white and red outline. Another lama walks in with an effigy made of dough concealed with a veil. The effigy is placed in the centre of the mandala on which a mantra is inscribed. The Bison Masked figure emerges from the hall. He dances with his troupe with symbols of death and destruction. He is accompained by eight dancers. The gruesome group in succession dance around the mandala. Four figures appear carrying a bell and a dorje accompanied by two lamas, one carries a samovar, the other four holy cups. These lamas make offerings of chang and barley grains to the four demon-deities. While the music plays on these four, empty the cups and chant the mantras, ringing their bells and swinging their dorjes. The ceremony of filling and emptying the cups is performed four times. The final episode of the dance drama displays the interplay between the teacher and the disciple. Once the ego, represented by the effigy is slain by the demon-deity with horned mask, all acts of reverence come to finality. It is now left for the tradition to remind the audience of the ‘eternal’ quality of the message sustained and preserved through a reverential teacher-pupil lineage.

Conclusion

The clam dances performed at the Hemis festival, embody a host of implicit meanings. Firstly, there is no concept of a dancer, as a dancer. The dancer is an empowered deity in the body of the human. Seen from this perspective, the monk dancer is a dancer-deity, whose human character undergoes a significant transformation through the masking process. The use of masks while it veils the immediate and mundane reality, simultaneously reveals another dimension of the divine, mythical beings and supersensible forces. The shifting of the boundaries between the sacred and the mundane and the transformation of the players from ascetic monkhood to the plane of the deity, reflects certain meaningful categories of Vajrayana Buddhism. The mask retains its significance as an image of transformation, whereby the dancer assumes the nature, posture and the very character of the deity. The most outstanding feature of the masked dance is their emphasis on the ideal of Bodhisattva represented by Padmasambhava, and the opposition between dharma and adharma. The origin of the cham dances goes back to year 811 AD when the guru Padmasambhava performed the black-hat chams to banish evil spirits who were an obstacle for building the Samaye monastery. Both these motifs, of the enlightened Boddhisattva as Padmasambhava, who had mastered the ten stages of Dharmameghabhumi by which he spreads the saddharma to wipe out the turbidities of beings, and the slaying of the enemies represented by the effigy are the two key motifs of the performance. The performance aims to bring out the grandeaur and majesty of Padmasambhava and the necessity of continuous renewal and reaffirmation of the Buddhadharma. Chams performance is characterized by nine dance movements, postures and gestures, and each of these has to be performed by every dancer-deity. Outside the scope of ritual, the monastic masked dance can be seen to reflect a certain social process. In the Hemis festival, the lamas and the lay people meet for a common aim of accumulating merit and resisting evil. The festival is a transmitter of this basic truth on which the foundation of Buddhism is based. The dance interprets some significant values that enshrine monastic life. When Lama Tashi Rabgias was questioned on the inner meaning of the horrific, leering, and ghoulish masks, he said:

"At death they will reappear again. The person will not be afraid of them. Having seen these dances year after year, one understands the nature of life and the meaning of death."

Thus, impermanence and death, are both transcended.