INTRODUCTION TO TANTRA ŚĀSTRA

INTRODUCTION TO TANTRA ŚĀSTRA

SIR JOHN WOODROFFE

MOUNT KAILĀSA

THE scene of the revelation of Mahānirvāna-Tantra is laid in Himālaya, the “Abode of Snow,” a holy land weighted with the traditions of the Āryan race. Here in these lofty uplands, encircled with everlasting snows, rose the great mountain of the north, the Sapta-KulaParvata. Hence the race itself came, and there its early legends have their setting. There are still shown at Bhimudiyar the caves where the sons of Pāṇ ḍ u and Draupadi rested, as did Rama and his faithful wife at the point where the Kosi joins the Sitā in the grove of Aśoka trees. In these mountains Munis and Ṛ ṣ is lived. Here also is the Kṣ etra of Śiva Mahādeva, where his spouse Parvatī, the daughter of the Mountain King, was born, and where Mother Ganges also has her source. From time immemorial pilgrims have toiled through these mountains to visit the three great shrines at Gangotri, Kedarnath and Badrinath. At Kangri, further north, the pilgrims make the parikrama of Mount Kailāsa (Kang Rinpoche), where Śiva is said to dwell. This nobly towering peak rises to the north-west of the

sacred Manasarowar Lake (Mapham Yum-tso) from amidst the purple ranges of the lower Kangri Mountains. The paradise of Śiva is a summerland of both lasting sunshine and cool shade, musical with the song of birds and bright with undying flowers. The air, scented with the sweet fragrance of Mandhāra chaplets, resounds with the music and song of celestial singers and players. The Mount is Gaṇ a-parvata, thronged with trains of Spirits (devayoni), of which the opening chapter of Mahānirvāṇ a-Tantra speaks. And in the regions beyond rises Mount Meru, centre of the world-lotus. Its heights, peopled with spirits, are hung with clusters of stars as with wreaths of Mālati flowers. In short, it is written: “He who thinks of Himācala, though he should not behold him, is greater than he who performs all worship in Kāśi (Benares). In a hundred ages of the Devas I could not tell thee of the glories of Himācala. As the dew is dried up by the morning sun, so are the sins of mankind by the sight of Himācala.” It is not, however, necessary to go to the Himālayan Kailāśa to find Śiva. He dwells wheresoever his worshippers, versed in Kula-tattva, abide, and His mystic mount is to be sought in the thousand-petalled lotus (sahasrarapadma) in the body of every human jīva, hence called Śiva-sthana, to which all, wheresoever situate, may repair when they have learned how to achieve the way thither.

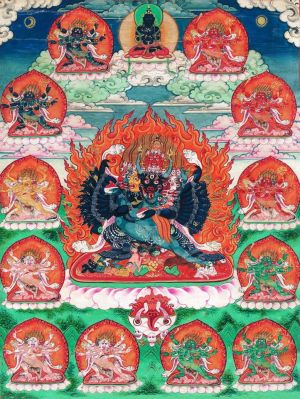

Śiva promulgates His teaching in the world below in the works known as Yāmala, Dāmara, Śiva-Sūtra, and in the Tantras which exist in the form of dialogues between the Devatā and his Śakti, the Devī in Her form as Pārvatī. According to the Gāyatri-Tantra, the Deva Gaṇ eśa first preached the Tantra to the Devayoni on Mount Kailāsa, after he had himself received them from the mouth of Śiva. After a description of the mountain, the dialogue opens with a question from Parvati in answer to which and those which succeed it, S’iva unfolds His doctrine on the subjects with which Mahā-nirvāṇ a-Tantra deals.

ŚIVA AND ŚAKTI

THAT eternal immutable existence which transcends the turiya and all other states in the unconditioned Absolute, the supreme Brahman or Para-brahman, without Prakṛ ti (niṣ kala) or Her attributes (nir-guṇ a), which, as being the inner self and knowing subject, can never be the object of cognition, and is to be apprehended only through yoga by the realization of the Self (ātma-jñāna), which it is. For, as it is said, “Spirit can alone know Spirit.” Being beyond mind, speech, and without name, the Brahman was called “Tat,” “That,” and then “Tat Sat,” “That which is.” For the sun, moon, and stars, and all visible things, what are they but a glimpse of light caught from “That” (Tat)? Brahman is both niṣ kala and sakala. Kalā is Prakṛ ti. The niṣ kala-Brahman or Para-brahman is the Tat when thought of as without Prakṛ ti (Prakṛ teranyā). It is called sakala when with Prakṛ ti.1 As the substance of Prakṛ ti is the three guṇ as It is then sa-guṇ a, as in the previous state It was nir-guṇ a. Though in the latter state It is thought of as without Śakti, yet (making accommodation to human speech) in It potentially exists Śakti, Its power and the whole universe produced by It. To say, however, that the Śakti exists in the Brahman is but a form of speech, since It and Śakti are, in fact, one,

̣ 1 Śārada-tilaka (chap. i), and chap. i. of Śāktānanda-tarangini (“Waves of Bliss of Śaktas), both Tantrika works of great authority.

and Śakti is eternal (Anādi-rūpā).1 She is Brahma-rūpā and both viguṇ a (nir-guṇ a) and sa-guṇ ā; the Caitanyarūpiṇ i-Devī, who Manifests all bhūta. She is the Ānandarūpiṇ ī Devī, by whom the Brahman manifests Itself,2 and who, to use the words of the Śārada, pervades the universe as does oil the sesamum seed. In the beginning the Niṣ kala-Brahman alone existed. In the beginning there was the One. It willed ̣ ̣ and became many. Aham-bahu-syām—“may I be many.” In such manifestation of Śakti the Brahman is known as the lower (apara) or manifested Brahman, who, as, the subject of worship, is meditated upon with attributes. And, in fact, to the mind and sense of the embodied spirit (jīva) the Brahman has body and form. It is embodied in the forms of all Devas and Devīs, and in the worshipper himself. Its form is that of the universe, and of all things and beings therein. ̣ As Śruti says: “He saw” (Sa aikṣ ata, aham bahu syām prajāyeya). He thought to Himself “May I be many.” “Sa aikṣ ata” was itself a manifestation of Śakti, the Paramāpūrva-nirvāṇ a-śakti of Brahman as Śakti.3 From the Brahman, with Śakti (Parahaktimaya) issued Nāda (Śiva-Śakti as the “Word” or “Sound”), and from Nāda, Bindu appeared. Kālicharana in his commentary on the Ṣ aṭ cakra-nirūpaṇ a4 says that Śiva and Nirvāṇ a- Śakti bound by a māyik bond and covering, should be ̣ thought of as existing in the form of Param Bindu.

̣ ̣ 1 Pranamya prakṛ tim nityam paramātma-svarūpinim (loc. cit. Śāktā-nanda-tarangiṇ i).

2 Kubjika-Tantra, 1st Patala.

3 Ṣ aṭ-cakra-nirupaṇ a. Commentary on verse 49, “The Serpent Power.” 4 Ibid., verse 37.

The Sāradā says: Saccidānanda-vibhavāt sakalāt parameśvarāt āsicchaktistato nādo, nadad bindusamudbhavah. (“From Parameśvara vested with the wealth of Saccidananda and with Prakṛ ti (sakala) issued Śakti; from Śakti came Nāda and from Nāda was born Bindu”). The state of subtle body which is known as Kāma-kalā is the mūla of mantra. The term mūlamantrātmikā, when applied to the Devī, refers to this subtle body of Hers known as the Kāma-kalā. The Tantra also speaks of three Bindus, namely, Śiva-maya, Śakti-maya, and Śiva-Śakti maya. ̣ The param-bindu is represented as a circle, the centre of which is the brahma-pada, or place of Brahman, wherein are Prakṛ ti-Puruṣ a, the circumference of which is encircling māyā. It is on the crescent of nirvāṇ a-kalā the seventeenth, which is again in that of amā-kalā, the sixteenth digit (referred to in the text) of the moon-circle

(Candra-maṇ ḍ ala), which circle is situate above the ̣ Sun-Circle (Sūrya-maṇ ḍ ala), the Guru and the Hamsah, which are in the pericarp of the thousand-petalled lotus (saharārapadrna). Next to the Bindu is the fiery Bodhinī, or Nibodhikā (v. post). The Bindu, with the Nirvāṇ a-kalā, Nibodhikā, and Amā-kalā, are situated in the lightning-like inverted triangle known as “A, Ka, Tha” and which is so called because at its apex is A; at its right base is Ka; and at its left base Tha. It is made up of forty-eight letters (mātṛ kā); the sixteen vowels running from A to Ka; sixteen consonants of the kavarga and other groups running from Ka to Tha; and the remaining sixteen from Tha to A. Inside are the remaining letters (mātṛ kā), ha, la (second), and kṣ a.1 As the substance of Devī is matṛ ka (mātṛ kāmayī) the triangle represents the “Word” of all that exists. The triangle is itself encircled by the Candra-maṇ ḍ ala. The Bindu is symbolically described as being like a grain of gram (caṇ aka), which under its encircling sheath ̣ contains a divided seed. This Param-bindu is prakṛ tiPuruṣ a, Śiva-Śakti.2 It is known as the Śabda-Brahman (the Sound Brahman), or Apara-brahman.3 A polarization of the two Śiva and Śakti-Tattvas then takes place in Paraśakti-maya. The Devī becomes Unmukhī. Her face turns towards Śiva. There is an unfolding which bursts the encircling shell of Māyā, and creation then takes place by division of Śiva and Śakti or of ̣ “Ham” and “Sah.” 4 The Śārada says: “The Devatāparaśakti-maya is again Itself divided, such divisions being known as Bindu, Bīja, and Nāda.5 Bindu is of the nature of Nāda of Śiva, and Bīja of Śakti, and Nāda has

1 Ṣ aṭ-cakra-nirupaṇ a. 2 Ṣ aṭ-cakra-nirupaṇ a, Commentary, verse 49. 3 Śārada-tilaka, (Chap. i): Bhidyamant parad bindoravyaktatmaravo’bhavat ̣ Śabda-brahmeti tam prāhuh. ̣ “From the unfolding Parambindu arose an indistinct sound. This bindu is called the Śabdu-brahman.”

4 Ṣ aṭ-cakra-nirupaṇ a, verse 49.

5 That is, tese are three different aspects of It.

been said to be the relation of these two by those who are verse in all the Āgamas.”1 The Śārada says that before the bursting of the shell enclosing the Brahmapada, which, together with its defining circumference, constitutes the Śabda-brahman, an indistinct sound arose (avyaktātmā-ravo’ bhavat). This avyaktanāda is both the first and the last state of Nāda, according as it is viewed from the standpoint of evolution or involution. For Nāda, as Rāghava-bhaṭ ṭ a 2 says, exists in three states. In Nāda are the guṇ as (sattva, rajas, and tamas), which form the substance of Prakṛ ti, which with Śiva It is. When tamo-guna predominates Nāda is merely an indistinct or unmanifested (dhvanyatmako’vyaktanādah3) sound in the nature of dhvani. In this state, in which it is a phase of Avyakta-nāda, it is called Nibodhikā, or Bodhinī. It is Nāda when rajo-guna is in the ascendant, when there is a sound in which there is something like a connected or combined disposition of the letters.4 When the sattva-guna preponderates Nāda assumes the form of Bindu.5 The action of rajas on tamas is to veil. Its own independent action effects an arrangement which is only perfected by the emergence of the essentially manifesting sattvika-guṇ a set into play by it. Nāda, Bindu, and Nibodhikā, and the Śakti,

1 Chapter 1:

Paraśaktimayah sākṣ at tridhāsau bhidyate punah. Bindurnādo bījam iti tasya bhedāh samīritah. ̣ Binduh Śivātmako bījam Śaktirnādastayormithah. Samavāyah samākhyatāh sarvāga-maviśaradaih. 2 See Commentary on verse 48 of the Ṣ aṭ-cakra-nirupaṇ a. 3 Tamo-guṇ ādhikyena kevala-dhvanyātmako’vyakta-nādah. Avyakta is lit. unspoken, hidden, unmanifest, etc. ̣ 4 Raja’adhikyena kimcidvarṇ a-nyāsātmakāh. 5 Sattv dhikyena bindurūpah.

of which they are the specific manifestations, are said to be in the form of Sun, Moon and Fire respectively. Jñāna (spiritual wisdom ) is spoken of as fire as it burns up all actions, and the tamo-guṇ a is associated with it. For when the effect of cause and effect of action are really known, then action ceases. Icchā is the Moon. The moon contains the sixteenth digit, the Amā-kalā with its nectar, which neither increases nor decays, and Icchā or will is the eternal precursor of creation. Kriyā is like Sun for as the Sun by its light makes all things visible, so unless there is action and striving there cannot be realization or manifestation. As the Gitā says: “As one Sun makes manifest all the lokas.” The Śabda-Brahman manifests Itself in a triad of energies—knowledge (jñānaśakti), will (icchā-śakti), and action (kriyā-śakti), associated with the three guṇ as of ̣ Prakṛ ti, tamas, sattva, and rajas. From the Param Bindu who is both bindvātmaka and kalātma—i.e., Śakti—issued Raudri, Rudra and his Śakti, whose forms are Fire (vahni), and whose activity is knowledge (jñāna); Vāmā and Viṣ ṇ u and his Śakti, whose form is the Sun and whose activity is Kriyā (action): and Jyeṣ ṭ ha and Brahma and his Śakti, whose form is the

Moon and whose activity is desire. The VāmakeśvaraTantra says that Tri-purā is three-fold, as Brahmā, Viṣ ṇ u and Īśa; and as the energies desire, wisdom and action;1 the energy of will when Brahman would create; the energy of wisdom when She reminds Him, saying “Let this be thus,” and when, thus knowing, He acts, She becomes the energy of action. The Devī is thus Icchā-śakti-jñāna-śakti-kriyā-śakti svarūpiṇ i.2 Para-Śiva exists as a septenary under the form, firstly, of Śambhu, who is the associate of time (Kālabandhu). From Him issues Sadā-Śiva, Who pervades and manifests all things, and then come Iśāna and the triad, Rudra, Viṣ ṇ u and Brahma, each with His respective Śakti (without whom they avail nothing3) separately and particularly associated with the guṇ as, tamas, sattva and rajas. Of these Devas, the last triad, together with Iśāna and Sadā-Śiva, are the five Śivas who are collectively known as the Mahā-preta, whose bīja is “Hsauh.” Of the Mahā-preta, it is said that the last four form the support and the fifth the seat, of the bed on which the Devī is united with Parama-śiva, in the room of cintāmani stone;4 on the jewelled island clad with clumps of kadamba and heavenly trees set in the ocean of Ambrosia.5

̣ 1 See Prāṇ a-toṣ ini (pp. 8, 9). Goraksha Sanmita and Bhuta-shuddhiTantra. See also Yoginī-Tantra, Part I, chap x. 2 Lalitā, verse 130 (see Bhāskararāya’s Commentary). 3 And so the Kubjika Tantra (chap. i) says : " Not Brahma, Viṣ ṇ u, Rudra create, maintain or destroy; but Brahmi, Vaiṣ navi, Rudrāni. Their husbands are as but dead bodies.”

4 The “stone which grants all desires” is described in the Rudrayāmala and Brahmānda-Purāṇ a. It is the place of origin of all those Mantras which bestow all desired objects (cintita). ̣ 5 See Ānandalahari of Samkarācarya, (verse 8), and Rudrayāmala. According to the Bahurpastaka and Bhairavayāmala, the bed is Śiva, the pillow Maheśana, the matting Śadaśiva, and the four supports Brahma, Hari, Rudra and Iśāna. Hence Devi is called Pancha-preta-mancādhisāyini (verse 174, Lalit sahasran āma).

Śiva is variously addressed in this work as Śambhu, ̣ Sadā-śiva, Śamkara, Maheśvara, etc., names which indicate particular states, qualities and manifestation of the One in its descent towards the many; for there are many Rudras. Thus Sadā-śiva indicates the predominance of the sattva-guṇ a. His names are many, 1,008 being given in the sixty-ninth chapter of the Śiva-Purāṇ a and in the seventeenth chapter of the Anuśāsana-Parvan of the Mahābharata.

Śakti is both māyā, that by which the Brahman creating the universe is able to make Itself appear to be different from what It really is, and mūla-prakṛ ti, or the unmanifested (avyakta) state of that which, when manifest, is the universe of name and form. It is the primary so-called “material cause,” consisting of the equipoise of the triad of guṇ a or “qualities” which are sattva (that which manifests), rajas (that which acts), tamas (that which veils and produces inertia). The three gunas represent Nature as the revelation of spirit, Nature as the passage of descent from spirit to matter, or of ascent from matter to spirit and nature as the dense veil of spirit. The Devī is thus guṇ a-nidhi (treasure-house of guṇ a). Mūla-prakṛ ti is the womb into which Brahman casts

the seed from which all things are born. The womb thrills to the movement of the essentially active rajo-guṇ a. The equilibrium of the triad is destroyed and the guṇ a, now in varied combinations, evolves under the illumination of Śiva (cit), the universe which is ruled by Maheśvara and Maheśvari. The dual principles of Śiva and Śakti, which are in such dual form the product of the polarity manifested in Parāśakti-maya, pervade the whole universe and are present in man in the Svayambhū-Linga of the muladhara and the Devī Kuṇ ḍ alinī, who, in serpent form, encircles it. The Śabda-Brahman assumes in the body of man the

form of the Devī Kuṇ ḍ alinī, and as such is in all prāṇ is (breathing creatures) and in the shape of letters appears in prose and verse. Kuṇ ḍ ala means coiled. Hence Kuṇ ḍ alinī, whose form is that of a coiled serpent, means that which is coiled. She is the luminous vital energy (jīva-śakti) which manifests as prāṇ a, She sleeps in the mūlādhāra and has three and a half coils corresponding in number with the three and a half bindus of which the Kubjikā-Tantra speaks. When after closing the ears the sound of Her hissing is not heard death approaches. From the first avyakta creation issued the second mahat, with its three guṇ as distinctly manifested. ̣ Thence sprung the third creation ahamkāra (selfhood), which is of threefold form—vaikārika, or pure sāttvika ̣ ̣ ahamkāra; the taijasa or rājasika ahamkāra; and the ̣ tāmasika or bhūtādika ahamkāra. The latter is the origin of the subtle essences (tanmātrā) of the Tattvas, ether, air, fire, water, earth, associated with sound, touch, sight, taste, and smell, and with the colours— pure transparency, śyāma, red, white, and yellow. There is some difference in the schools as to that which each of the three forms produces but from such threefold ̣ form of Ahamkāra issue the indriyas (“senses,” and the Devas Dik, Vāta, Arka, Pracetas, Vahni, Indra, Upendra, Mitra, and the Aśvins. The vaikārika, taijasa, and bhūtādika are the fourth, fifth, and sixth creations, which are known as prākrita, or appertaining to Prakṛ ti. The rest, which are products of these, such as the vegetable world with its upward life current, animals with horizontal life current and bhūta, preta and the like, whose life current tends downward, constitute the vaikrta creation, the two being known as the kaumāra creation. The Goddess (Devī) is the great Śakti. She is Māyā ̣ for of Her the māyā which produces the samsāra is. As Lord of māyā She is Mahāmāyā. Devī is avidyā (nescience) because She binds and vidya (knowledge) because ̣ She liberates and destroys the samsara. She is Pra kṛ ti, and as existing before creation is the Ādyā (primordial) Śakti. Devī is the vācaka-śakti, the manifestation of Cit in Prakṛ ti, and the vāchya-Śakti, or Cit itself. The Ātmā should be contemplated as Devī. Śakti or Devī is thus the Brahman revealed in Its mother aspect (Śri-māta) as Creatrix and Nourisher of the worlds. Kālī says of Herself in Yogini-Tantra:6 “Sacciḍ

ānanda-rūpāham brahmai-vāhām sphurat-prabham.” So the Devī is described with attributes both of the qualified Brahman and (since that Brahman is but the manifestation of the Absolute) She is also addressed with epithets, which denote the unconditioned Brahman. She is the great Mother (Ambikā) sprung from the sacrificial hearth of the fire of the Grand consciousness (cit); decked with the Sun and Moon; Lalitā, “She who plays”; whose play is world-play; whose eyes playing like fish in the beauteous waters of her Divine face, open and shut with the appearance and disappearance of countless worlds now illuminated by her light, now wrapped in her terrible darkness.

The Devī, as Para-brahman, is beyond all form and guṇ a. The forms of the Mother of the Universe are threefold. There is first the Supreme (para) form, of which, as the Viṣ ṇ u-yāmala says, “none knows.” There is next her subtle (Sūkṣ ma) form, which consists of mantra. But as the mind cannot easily settle itself upon that which is formless, She appears as the subject of contemplation in Her third, or gross (Sthūla), or physical form, with hands and feet and the like as celebrated in the Devīstotra of the Purānas and Tantras. Deṿ ī, who as Prakṛ ti is the source of Brahma, Viṣ ṇ u, and Maheśvara, has both male and female forms.1 But it is in Her female forms that she is chiefly contemplated. For though existing in all things, in a peculiar sense female beings are parts of Her.2 The Great Mother, who exists in the form of all Tantras and all Yantras,3 is, as the Lalita says, the “unsullied treasure-house of beauty”; the Sapphire Devī, whose slender waist, bending beneath the burden of the ripe fruit of her breasts, wells into jewelled hips heavy with the promise of infinite maternities.

As the Mahadevi She exists in all forms as Sarasvatī, Lakṣ mi, Gāyatrī, Durgā, Tripurā-sundarī,

1 Ibid., chap. iii, which also says that there is no eunuch form of God. 2 So in the Candi (Mārkandeya-Purāna) it is said:

Vidyah samastastava devī bhedah Striyah samastāh sakalā jagatsu.

See author’s “Hymns to the Goddess.” The Tantrika more than all men, recognises the divinity of woman, as was observed centuries past by the Author of the Dabistān. The Linga-Purāna also after describing Arundhati, Anasūyā, and Shachi to be each the manifestation of Devī, concludes: “All things indicated by words in the feminine gender are manifestations of Devī.” 3 Sarva-tantra-rūpā; Sarva-yantrātmikā (see Lalitā, verses 205-6). Annapūrṇ ā, and all the Devīs who are avataras of the Brahman.

Devi, as Sati, Umā, Parvati, and Gaūrī, is spouse of Śiva. It was as Sati prior to Dakṣ a’s sacrifice (dakṣ ayajna) that the Devī manifested Herself to Śiva in the ten celebrated forms known as the daśa-mahāvidya referred to in the text—Kālī, Bagalā, Chinnamastā, Bhuvaneśvarī, Mātanginī, Shodaśi, Dhūmāvatī, Tripurasundari, Tārā, and Bhairavī. When, at the Dakṣ ayajna She yielded up her life in shame and sorrow at the treatment accorded by her father to Her Husband, Śiva took away the body, and, ever bearing it with Him, remained wholly distraught and spent with grief. To save the world from the forces of evil which arose and grew with the withdrawal of His Divine control, Viṣ ṇ u with His discus (cakra) cut the dead body of Sati, which Śiva bore, into fifty -one fragments, which fell to earth at the places thereafter known as the fifty-one mahāpītha-sthāna (referred to in the text), where Devī, with Her Bhairava, is worshipped under various names.

Besides the forms of the Devī in the Brahmāṇ ḍ a, there is Her subtle form Kuṇ ḍ alinī in the body (piṇ ḍ āṇ da). These are but some only of Her endless forms. She is seen as one and as many, as it were, but one moon reflected in countless waters. She exists, too, in all animals and inorganic things, the universe with all its beauties is, as the Devī Purāṇ a says but a part of Her. All this diversity of form is but the infinite manifestation of the flowering beauty of the One Supreme Life, a doctrine which is nowhere else taught with greater wealth of illustration than in the Śākta-Śāstras and Tantras. The great Bharga in the bright Sun and all devatas, and indeed, all life and being, are wonderful, and are worshipful but only as Her manifestations. And he who worships them otherwise is, in the words of the great Devī-bhāgavata, “like unto a man who, with the light of a clear lamp in his hands, yet falls into some waterless and terrible well.” The highest worship for which the sādhaka is qualified (adhikāri) only after external worship and that internal form known as sādhāra, is described as nirādhārā. Therein Pure Intelligence is the Supreme Śakti who is worshipped as the very Self, the Witness freed of the glamour of the manifold Universe. By one’s own direct experience of Maheśvari as the Self She is with reverence made the object of that worship which leads to liberation.

GU Ṇ A

IT cannot be said that current explanations give a clear understanding of this subject. Yet such is necessary, both as affording one of the chief keys to Indian philosophy and to the principles which govern Sādhana. The term guṇ a is generally translated “quality,” a word which is only accepted for default of a better. For it must not be overlooked that the three guṇ as (Sattva, rajas, and tamas) which are of Prakṛ ti constitute Her very substance. This being so, all Nature which issues from Her, the Mahākāraṇ asvarūpa, is called triguṇ ātmaka, and is composed of the same guṇ a in different states of relation to one another. The functions of sattva, rajas, and tamas are to reveal, to make active, and to suppress respectively. Rajas is the dynamic, as sattva and tamas are static principles. That is to say, sattva and tamas can neither reveal nor suppress without being first rendered active by rajas. These guṇ as work by mutual suppression.

The unrevealed Prakṛ ti (avyakta-prakṛ ti) or Devī is the state of stable equilibrium of these three guṇ as. When this state is disturbed the manifested universe appears, in every object of which one or other of the three guṇ as is in the ascendant. Thus in Devas as in those who approach the divya state, sattva predominates, and rajas and tamas are very much reduced. That is, their independent manifestation is reduced. They are in one sense still there, for where rajas is not independently active it is operating on sattva to suppress tamas, which appears or disappears to the extent to which it is, or is not, subject to suppression by the revealing principle. In the ordinary human jīva considered as a class, tamas is less reduced than in the case of the Deva but very much reduced when comparison is made with the animal jīva. Rajas has great independent activity, and sattva is also considerably active. In the animal creation sattva has considerably less activity. Rajas has less independent activity than in man, but is much more active than in the vegetable world. Tamas is greatly less preponderant than in the latter. In the vegetable kingdom tamas is more preponderant than in the case of animals and both rajas and sattva less so. In the inorganic creation rajas makes tamas active to suppress both sattva and its own independent activity. It will thus be seen that the “upward” or revealing movement from the predominance of tamas to that of sattva represents the spiritual progress of the jīvātmā. Again, as between each member of these classes one or other of three guṇ as may be more or less in the ascendant.

Thus, in one man as compared with another, the sattva guṇ a may predominate, in which case his temperament is sāttvik, or, as the Tantra calls it, divyabhāva. In another the rajoguṇ a may prevail, and in the third the tāmoguṇ a, in which case the individual is described as rājasik, or tāmasik, or, to use Tantrik phraseology, he is said to belong to virabhāva, or is a paśu respectively. Again the vegetable creation is obviously less tāmasik and more rājasik and sāttvik than the mineral, and even amongst these last there may be possibly some which are less tāmasik than others.

Etymologically, sattva is derived from “sat,” that which is eternally existent. The eternally existent is also Cit, pure Intelligence or spirit, and Ānanda or Bliss. In a secondary sense, sat is also used to denote the “good.” And commonly (though such use obscures the original meaning), the word sattva guṇ a is rendered “good quality.” It is, however, “good” in the sense that it is productive of good and happiness. In such a case, however, stress is laid rather on a necessary quality or effect (in the ethical sense) of ‘sat’ than upon its original meaning. In the primary sense sat is that which reveals. Nature is a revelation of spirit (sat). Where Nature is such a revelation of spirit there it manifests as sattva guṇ a. It is the shining forth from under the veil of the hidden spiritual substance (sat). And that quality in things which reveals this is sattva guna. So of a pregnant woman it is said that she is antahsattva, or instinct with sattva; she in whom sattva as jīva (whose characteristic guṇ a is sattva) is living in a hidden state. But Nature not only reveals, but is also a dense covering or veil of spirit, at times so dense that the ignorant fail to discern the spirit which it veils. Where Nature is a veil of spirit there it appears in its quality of tamoguṇ a.

In this case the tamoguṇ a is currently spoken of as representative of inertia, because that is the effect of the nature which veils. This quality, again, when translated into the moral sphere, becomes ignorance, sloth, etc. In a third sense nature is a bridge between spirit which reveals and matter which veils. Where Nature is a bridge of descent from spirit to matter, or of ascent from matter to spirit there it manifests itself as rajoguṇ a. This is generally referred to as the quality of activity, and when transferred to the sphere of feeling it shows itself as passion. Each thing in nature then contains that in which spirit is manifested or reflected as in a mirror or sattvaguṇ a; that by which spirit is covered, as it were, by a veil of darkness or tamoguṇ a, and that which is the vehicle for the descent into matter or the return to spirit or rajoguṇ a. Thus sattva is the light of Nature, as tamas is its shade. Rajas is, as it were, a blended tint oscillating between each of the extremes constituted by the other guṇ as.

The object of Tantrik sādhana is to bring out and make preponderant the sattva guṇ a by the aid of rajas, which operates to make the former guṇ a active. The subtle body (lingaśarīra) of the jīvatma comprises in it ̣ buddhi, ahamkāra, manas, and the ten senses. This subtle body creates for itself gross bodies suited to the spiritual state of the jīvatma. Under the influence of prārabdha karma, buddhi becomes tāmasik, rājasik, or sāttvik. In the first case the jīvatma assumes inanimate bodies; in the second, active passionate bodies; and in the third, sattvik bodies of varying degress of spiritual excellence, ranging from man to the Deva. The gross body is also triguṇ ātmaka. This body conveys impressions to the jīvātma through the subtle body and the buddhi in particular. When sattva is made active impressions of happiness result, and when rajas or tamas are active the impressions are those of sorrow and delusion. These impressions are the result of the predominance of these respective guṇ as. The acting of rajas on sattva produces happiness, as its own indepen-

dent activity or operation on tamas produces sorrow and delusion respectively. Where sattva or happiness is predominant, there sorrow and delusion are suppressed. Where rajas or sorrow is predominant, there happiness and delusion are suppressed. And where tamas or delusion predominates there, as in the case of the inorganic world, both happiness and sorrow are suppressed. All objects share these three states in different proportions. There is, however, always in the jīvātma an admixture of sorrow with happiness, due to the operation of rajas. For happiness, which is the fruit of righteous acts done to attain happiness, is after all only a vikāra. The natural state of the jīvātma—that is, the state of its own true nature—is that bliss (ānanda) which arises from the pure knowledge of the Self, in which both happiness and sorrow are equally objects of indifference. The worldly enjoyment of a person involves pain to self or

others. This is the result of the pursuit of happiness, whether by righteous or unrighteous acts. As spiritual progress is made, the gross body becomes more and more refined. In inanimate bodies, karma operates to the production of pure delusion. On the exhaustion of such karma, the jīvātma assumes animate bodies for the operation of such forms of karma as lead to sorrow and happiness mixed with delusion. In the vegetable world, sattva is but little active, with a corresponding lack of discrimination, for discrimination is the effect of sattva in buddhi, and from discrimination arises the recognition of pleasure and pain, conceptions of right and wrong, of the transitory and intransitory, and so forth, which are the fruit of a high degree of discrimination, or of activity of sattva. In the lower animal, sattva in buddhi is not suficiently active to lead to any degree of development of these conceptions. In man, however, the sattva in buddhi is considerably active, and in consequence these conceptions are natural in him. For this reason the human birth is, for spiritual purposes, so important. All men, however, are not capable of forming such conceptions in an equal degree. The degree of activity in an individual’s buddhi depends on his prārabdha karma. However bad such karma may be in any particular case, the individual is yet gifted with that amount of discrimination which, if properly aroused and aided, will enable him to better his spiritual condition by inducing the rajoguṇ a in him to give more and more activity to the sattva guṇ a in his buddhi.

On this account proper guidance and spiritual direction are necessary. A good guru, by reason of his own nature and spiritual attainment and disinterested wisdom, will both mark out for the śiṣ ya the path which is proper for him, and aid him to follow it by the infusion of the tejas which is in the Guru himself. Whilst sādhana is, as stated, a process for the stimulation of the sattva guṇ a, it is evident that one form of it is not suitable to all. It must be adapted to the spiritual condition of the śiṣ ya, otherwise it will cause injury instead of good. Therefore it is that the adoption of certain forms of sādhana by persons who are not competent (adhikāri), may not only be fruitless of any good result, but may even lead to evils which sādhana as a general principle is designed to prevent. Therefore also is it said that is it better to follow one’s own dharma than that, however exalted it be, of another.

THE WORLDS (LOKAS)

THIS earth, which is the object of the physical senses and of the knowledge based thereon, is but one of fourteen worlds or regions placed “above” and “below” it, of which (as the sūtra says1) knowledge may be obtained by meditation on the solar “nerve” (nāḍ i) suṣ umṇ ā in the merudaṇ ḍ a. On this nāḍ i six of the upper worlds are threaded, the seventh and highest overhanging it in the Sahasrāra-Padma, the thousand-petalled lotus. The sphere of earth (Bhūrloka), with its continents, their mountains and rivers, and with its oceans, is the seventh or lowest of the upper worlds. Beneath it are the Hells and Nether World, the names of which are given below. Above the terrestrial sphere is Bhuvarloka, or the atmospheric sphere known as the antarikṣ ā, extending “from the earth to the sun,” in which the Siddhas and other celestial beings (devayoni) of the upper air dwell. “From the sun to the pole star” (dhruva) is svarloka, or the heavenly sphere. Heaven (svarga) is that which delights the mind, as hell (naraka) is that which gives it pain.2 In the former is the abode of the Deva and the blest.

These three spheres are the regions of the consequences of work, and are termed transitory as compared

̣ ̣ 1 Bhuvanajnānam sūrye samyamāt, Patanjali's Yoga-Sutra (chap. iii, 26). An account of the lokas is given in Vyāsa’s commentary on the sūtra, in the Viṣ ṇ u-Purāṇ a (Bk. II, chaps. v-vii): and in the Bhāgavata, Vāyu, and other Purāṇ as.

2 Viṣ ṇ u-Purāṇ a (Bk. II; chap. vi). Virtue is heaven and vice is hell, ibid, ̣ Narakamināti = kleśam prāpayati, or giving pain.

with the three highest spheres, and the fourth, which is of a mixed character. When the jīva has received his reward he is reborn again on earth. For it is not good action, but the knowledge of the Ātmā which procures Liberation (mokṣ a). Above Svarloka is Maharloka, and above it the three ascending regions known as the janaloka, tapoloka, and satyaloka, each inhabited by various forms of celestial intelligence of higher and higher degree. Below the earth (Bhah) and above the nether worlds are the Hells (commencing with Avichi), and of which, according to popular theology, there are thirty-four though it is elsewhere said there are as many hells as there are offences for which particular punishments are meted out. Of these six are known as the great hells. Hinduism, however, even when popular, knows nothing of a hell of eternal torment. To it nothing is eternal but the Brahman. Issuing from the Hells the jīva is again reborn to make its future. Below the Hells are the seven nether worlds, Sutala, Vitala, Talātala, Mahātala, Rasātala, Atala, and Pātāla, where, according to the Purāṇ as, dwell the Nāga serpent divinities, brilliant with jewels, and Dānavas wander, fascinating even the most austere. Yet below Pātāla is the form of Viṣ ṇ u proceeding from the dark quality (tamoguṇ ah), known as the Seṣ a serpent or Ananta bearing the entire world as a diadem, attended by his Śakti Vāruṇ ī, his own embodied radiance.

INHABITANTS OF THE WORLDS

THE worlds are inhabited by countless grades of beings, ranging from the highest Devas (of whom there are many classes and degrees) to the lowest animal life. The scale of beings runs from the shining manifestations to the spirit of those in which it is so veiled that it would seem almost to have disappeared in its material covering. There is but one Light, one Spirit, whose manifestations are many. A flame enclosed in a clear glass loses but little of its brilliancy. If we substitute for the glass, paper, or some other more opaque yet transparent substance, the light is dimmer. A covering of metal may be so dense as to exclude from sight the rays of light which yet burns within with an equal brilliancy. As a fact, all such veiling forms are māyā. They are none the less true for those who live in and are themselves part of the māyik world. Deva, or “heavenly and shining one”— for spirit is light and self-manifestation—is applicable to those descending yet high manifestations of the Brahman, such as the seven Śivas, including the Trinity (trimūrti), Brahma, Viṣ ṇ u, and Rudra. Devī again, is the title of the Supreme Mother Herself, and is again applied to the manifold forms assumed by the one only Māyā, such as Kālī, Sarasvatī, Lakṣ mī, Gaurī, Gāyatrī, ̣ Samdhyā, and others. In the sense also in which it is said, “Verily, in the beginning there was the Brahman. It created the Devas”; the latter term also includes lofty intelligences belonging to the created world intermediate between Īśvara (Himself a Puruṣ a) and man, who in the person of the Brāhmaṇ a is known as Earthdeva (bhūdeva). These spirits are of varying degrees. For there are no breaks in the creation which represents an apparent descent of the Brahman in gradually lowered forms. Throughout these forms play the divine currents of pravṛ tti and nivṛ tti, the latter drawing to Itself that which the former has sent forth.

Deva, jīva and jada (inorganic matter) are, in their real, as opposed to their phenomenal and illusory being, the one Brahman, which appears thus to be other than Itself through its connection with the upādhi or limiting conditions with which ignorance (avidyā) invests it. Therefore all being which are the object of worship are each of them but the Brahman seen though the veil of avidyā. Though the worshippers of Devas may not know it, their worship is in reality the worship of the Brahman, and hence the Mahānirvāṇ a-Tantra says that, “as all streams flow to the ocean, so the worship given to any Deva is received by the Brahman.” On the other hand, those who, knowing this, worship the Devas, do so as manifestations, of Brahman, and thus worship It

mediately. The sun, the most glorious symbol in the physical world, is the māyik vesture of Her who is “clothed with the sun.” In the lower ranks of the celestial hierarchy are the Devayonis, some of whom are mentioned in the opening verses of the first chapter of the text. The Devas are of two classes: “unborn” (ajāta)—that is, those which have not, and those which have (sādhya) evolved from humanity as in the case of King Nahusa, who became Indra. Opposed to the divine hosts are the Asura, Dānavā, Daitya, Rākṣ asa, who, with other spirits, represent the tamasik or demonic element in creation. All Devas, from the highest downwards, are subordinate to both time and karma. So it is said, “Salutation to Karma, over which not even Vidhi

(Brahmā), prevails” (Namastat karmabhyovidhirapi na yebhyah prabhavati). The rendering of the term “Deva” as “God” has led to a misapprehension of Hindu thought. The use of the term “angel” may also mislead, for though the world of Devas has in some respects analogy to the angelic choirs, the Christian conception of these Beings, their origin and functions, does not include, but in fact excludes, other ideas connoted by the Sanskrit term.

The pitṛ s, or “Fathers,” are a creation (according to some) separate from the predecessors of humanity, and are, according to others, the lunar ancestry who are addressed in prayer with the Devas. From Brahma, who is known as the “Grandfather,” Pitā Mahā of the human race, issued Marichi, Atri, and others, his “mental sons”: the Agniṣ vāttāh, Saumsaya, Haviṣ mantah, Usmapāh, and other classes of Pitṛ s, numbering, according to the Mārkaṇ ḍ eya Purāṇ a, thirty-one. Tarpaṇ am, or oblation, is daily offered to these pitṛ s. The term is also applied to the human ancestors of the worshipper generally up to the seventh generation to whom in śrāddha (the obsequial rites) piṇ ḍ a and water are offered with the mantra “svadhā.”

The Ṛ ṣ is are seers who know, and by their knowledge are the makers of Śāstra and “see” all mantras.

The word comes from the root ṛ ṣ ;1 Ṛ ṣ ati-prāpnoti sar-

̣ ̣

vam mantram jnānena paśyati sangsārapārangvā, etc. The seven great Ṛ ṣ is or saptaṛ ṣ is of the first manvantara are Marīcī, Atri, Angiras, Pulaha, Kratu, Pulastya, and Vaśiṣ ṭ ha. In other manvantaras there are other saptaṛ ṣ is. In the present manvantara the seven are Kāśyapa, Atri, Vaśiṣ tha, Viśvāmitra, Gautama, Jamadagni, Bharadvāja. To the Ṛ ṣ is the Vedas were revealed. Vyāsa taught the Ṛ gveda so revealed to Paila, the Yajurveda to Vaisampayana, the Sāmaveda to

Jaimini, Atharvāveda to Sumantu, and Itihāsa and

Dogm, tom. III. The cabalistic names of the nine orders as given by Archangelus at p. 728 of his “Interpretationes in artis Cabalistice scriptores“ 1587). 1 Śabdakalpadruma.

Purāṇ a to Sūta. The three chief classes of Ṛ ṣ is are the Brahmaṛ ṣ i, born of the mind of Brahma, the Devaṛ ṣ i of lower rank, and Rājaṛ ṣ i or Kings who became Ṛ ṣ is through their knowledge and austerities, such as Janaka, Ṛ tapārṇ a, etc. The Śrutaṛ ṣ i are makers of Śastras, as Śuśruta. The Kāndaṛ ṣ i are of the Karmakānda, such as Jaimini.

The Muni, who may be a Ṛ ṣ i, is a sage. Muni is so called on account of his mananam (mananāt munirucyate). Mananam is that thought, investigation, and discussion which marks the independent thinking mind. First there is Śravanam, listening; then Mananam, which is the thinking or understanding, discussion upon, and testing of what is heard as opposed to the mere acceptance on trust of the lower intelligence. ̣ These two are followed by Nididhyāsanam, which is attention and profound meditation on the conclusions (siddhānta) drawn from what is so heard and reasoned upon. As the Mahabharata says, “The Vedas differ, and so do the Smṛ tis. No one is a muni who has no inde- ̣ pendent opinion of his own (nāsau muniryasya matam na bhinnam).” The human being is called jīva —that is, the embodied Ātmā possessed by egoism and of the notion that it directs the puryaṣ taka, namely, the five organs of action (karmendriya), the five organs of perception (jnānendriya), the fourfold antahkarana or mental self (Manas, ̣ Buddhi, Ahamkāra, Citta), the five vital airs (Prāṇ a), the five elements, Kāma (desire), Karma (action and its results), and Avidyā (illusion). When these false notions are destroyed, the embodiment is destroyed, and the wearer of the māyik garment attains nirvāṇ a. When the jīva is absorbed in Brahman, there is no longer any jīva remaining as such.

VARṆA ORDINARILY

there are four chief divisions or castes (varṇ a) of Hindu society—viz.: Brāhmaṇ a (priesthood; teaching); Kṣ attriya (warrior); Vaiśya (merchant); Śūdra (servile) said to have sprung respectively from the mouth, arm, thigh, and foot of Brahma. A man of the first three classes becomes on investiture, during the upanayana ceremony of the sacred thread, twice-born (dvija). It is said that by birth one is sūdra, by ̣ samskāra (upanayana) dvija (twice born); by study of the Vedas one attains the state of a vipra; and that he who has knowledge of the Brahman is a Brāhmaṇ a.1 The present Tantra, however, speaks of a fifth or hybrid class (sāmānya), resulting from intermixture between the others. It is a peculiarity of Tantra that its worship is largely free of Vaidik exclusiveness, whether based on caste, sex or otherwise. As the Gautamiya-Tantra says, “The Tantra is for all men, of whatever caste, and for all ̣ women” (Sarvavarṇ ādhikāraśca nāriṇ ām yogya eva ca).

1 Janmanā jāyate Śūdrah ̣ Samskārād dvija ucyate Veda-pāthat bhavet viprah Brahma jṇ ānāti brāhmaṇ āh.

ĀŚRAMA

THE four stages, conditions, or periods in the life of a Brāhmaṇ a are: first, that of the chaste student, or brahmacāri; second, the period of secular life as a married house-holder or gṛ hastha; third, that of the recluse, or vānaprastha, when there is retirement from the world; and lastly, that of the beggar, or bhikṣ u, who begs his single daily meal, and meditates upon the Supreme Spirit to which he is about to return. For the Kṣ attriya there are the first three Aśramas; for the Vaiśya, the first two; and for the Śūdra, the gṛ hastha Āśrama only. This Tantra states that in the Kali age there are only two Āśramas. The second gṛ hasthya and the last bhikṣ uka or avadhūta. Neither the conditions of life, nor the character, capacity, and powers of the people of this age allow of the first and third. The two āśramas prescribed for Kali age are open to all castes indicriminately. There are, it is now commonly said, two main divisions of avadhūta—namely, Śaivāvadhūta and Brahmāvadhūta—of each of which there are, again, three divisions. Of the first class the divisions are firstly, Śaivāvadhūta, who is apūrṇ a (imperfect). Though an

ascetic, he is also a householder and like Śiva. Hence his name. The second is the wandering stage of the Śaiva (or the parivrājaka), who has now left the world, and passes his time doing pūjā, japa, etc., visiting the tīrtha and pīṭ ha, or places of pilgrimage. In this stage, which though higher, is still imperfect, the avadhūta is competent for ordinary sādhana with a śakti. The third is the perfect stage of a Śaiva. Wearing only the kaupīna,1 he renounces all things and all rites, though within certain limits he may practise some yoga, and is permitted to meet the request of a woman who makes it of him.2 Of the second class the three divisions are, firstly, the Brahmāvadhūta, who, like the Śaivāvadhūta, is imperfect (apūrṇ a) and householder. He is not permitted, however, to have a Śaiva Śakti, and is restricted to svīyaśakti. The second class Brahmaparivrājaka is similar to the Śaiva of the same class except that ordinarily he is not permitted to have anything to do with any woman, though he may, under the guidance of his

Guru, practise yoga accompanied by Śakti. The third or

̣

highest class—Hamsāvadhata—is similar to the third Śaiva degree, except that he must under no circumstances touch a woman or metals, nor may he practise any rites or keep any observances.

1 The exiguous loin cloth of ascetics covering only the genitals. See the ̣ kaupīnapañcakam of Śamkarācāryā, where the Kaupīnarān is described as the fortunate one living on the handful of rice got by begging; ever pondering upon the words of the Vedānta, whose senses are in repose, who ever enjoys the Brahman in the thought Ahambrahmāsmi. 2 This is not, however, as some may suppose, a peculiarly “Tāntrik” ̣ precept, for it is said in Śruti “talpāgatām na pariharet” (she who comes to your bed is not to be refused), for the rule of chastity which is binding on him ̣ yields to such an advance on the part of woman. Śamkarācāryā says that ̣ talpāgatām is samāgamarthinim, adding that this is the doctrine of Ṛ ṣ i Vāmadeva.

MACROCOSM AND MICROCOSM

THE universe consists of a Mahābrahmāṇ ḍ a, or grand Cosmos, and of numerous Bṛ hatbrahmāṇ ḍ a, or macrocosms evolved from it. As is said by the Nirvāṇ aTantra, all which is in the first is in the second. In the latter are heavenly bodies and beings, which are microcosms reflecting on a minor scale the greater worlds which evolve them. “As above, so below.” The mystical maxim of the West is stated in the Viśvasāra-Tantra as follows: “What is here is elsewhere; what is not here is nowhere” (yadhihāsti tadanyatra yannehāsti na tatkvacit). The macrocosm has its meru, or vertebral column, extending from top to bottom. There are fourteen regions descending from Satyaloka, the highest. These are the seven upper and the seven nether worlds (vide ante). The meru of human body is the spinal column, and within it are the cakras, in which the worlds are said to dwell. In the words of the Śāktānanda-Tarangiṇ ī, they are piṇ ḍ amadhyesthitā. Satya has been said to be in the sahasrārā, and Tapah, Janah, Mahah, Svah, Bhuvah, Bhūh in the ājnā, viśuddhi, anahata, maṇ ipūra, svādhiṣ ṭ hāna, and mūlādhāra lotuses respectively. Below mūlādhāra and in the joints, sides, anus, and organs of generation are the nether worlds. The bones near the spinal column are the kulaparvata. Such are the correspondences as to earth. Then as to water. The nadis are the rivers. The seven substances of the body

(dhatu) are the seven islands. Sweat, tears, and the like are the oceans. Fire exists in the mūlādhāra, suṣ umṇ ā, navel and elsewhere. As the worlds are supported by the prāṇ a and other vāyus (“airs”), so is the body supported by the ten vāyus, prāṇ a, etc. There is the same ākāśa (ether) in both. The witness within is the puruṣ a without, for the personal soul of the microcosm corresponds to the cosmic soul (hiraṇ yagarbha) in the macrocosm. THE AGES

THE passage of time within a mah ā-yuga influences for the worse man and the world in which he lives. This passage is marked by the four ages (yuga), called Satya, Treta, Dvāpara, and Kali-yuga, the last being that in which it is generally supposed the world now is. The yuga is a fraction of a kalpa, or day of Brahmā of 4,320,000,000 years. The kalpa, is divided into fourteen manvantaras, which are again subdivided into seventyone mahā yuga; the length of each of which is 4,320,000 human years. The mahā-yuga (great age) is itself composed of four yuga (ages)—(a) Satya, (b) Treta, (c) Dvapara, (d) Kali. Official science teaches that man appeared on the earth in an imperfect state, from which he has since been gradually, though continually, raising himself. Such teaching is, however, in conflict with the traditions of all peoples—Jew, Babylonian, Egyptian, Hindu, Greek, Roman, and Christian—which speak of an age when man was both innocent and happy. From this state of primal perfection he fell, continuing his descent until such time as the great Avatāras, Christ and others, descended to save his race and enable it to regain the righteous path. The Garden of Eden is the emblem of the paradisiacal body of man. There man was one with Nature. He was himself paradise, a privileged enclosure in a garden of delight —gan be Eden. Et eruditus est Moyse omni sapientia Ægyptiorum.

The Satya Yuga is, according to Hindu belief, the Golden Age of righteousness, free of sin, marked by longevity, physical strength, beauty, and stature. “There were giants in those days” whose moral, mental, and physical strength enabled them to undergo long brahmacārya (continence) and tapas (austerities). Longevity permitted lengthy spiritual exercises. Life then depended on the marrow, and lasted a lakh of years, men dying when they willed. Their stature was 21 cubits. To this age belong the Avatāras or incarnations of Viṣ ṇ u, ̣ Matsya, Kūrma, Varāha, Nṛ -simha, and Vāmana. Its duration is computed to be 4,800 Divine years, which, when multiplied by 360 (a year of the Devas being equal to 360 human years) are the equivalent of 1,728,000 of the years of man. The second age, or Treta (three-fourth) Yuga, is that in which righteousness (dharma) decreased by onefourth. The duration was 3,600 Divine years, or 1,296,000 human years. Longevity, strength, and stature decreased. Life was in the bone, and lasted 10,000 years. Man's stature was 14 cubits. Of sin there appeared onequarter, and of virtue there remained three-quarters. Men were still attached to pious and charitable acts, penances, sacrifice and pilgrimage, of which the chief was that to Naimiśāraṇ ya. In this period appeared the avatāras of Viṣ ṇ u as Paraśurāma and Rāma. The third, or Dvāpara (one-half) yuga, is that in which righteousness decreased by one-half, and the

duration was 2,400 Divine, or 864,000 human years. A further decrease in longevity and strength, and increase of weakness and disease mark this age. Life which lasted 1,000 years was centred in the blood. Stature was 7 cubits. Sin and virtue were of equal force. Men became restless, and though eager to acquire knowledge, were deceitful, and followed both good and evil pursuits. The principal place of pilgrimage was Kurukṣ etra. To this age belongs (according to Vyāsa, Anuṣ tubhācaryā and Jaya-deva) the avatāra of Viṣ ṇ u as Bala-rāma, the elder brother of Kṛ ṣ ṇ a, who, according to other accounts, takes his place. In the samdhya, or intervening period of 1,000 years between this and the next yuga the Tantra was revealed, as it will be revealed at the dawn of every Kali-yuga.

Kali-yuga is the alleged present age, in which righteousness exists to the extent of one-fourth only, the duration of which is 1,200 Divine, or 432,000 human years. According to some, this age commenced in 3120 B. C. on the date of Viṣ ṇ u’s return to heaven after the eighth incarnation. This is the period which, according to the Purāṇ as and Tantras, is characterized by the prevalence of viciousness, weakness, disease, and the general decline of all that is good. Human life, which lasts at most 120, or, as some say, 100, years, is dependent on food. Stature is 3½ cubits. The chief pilgrimage is now to the Ganges. In this age has appeared the Buddha Avatāra. The last, or Kalki Avatāra, the Destroyer of sin, has yet to come. It is He who will destroy iniquity and restore the age of righteousness. The Kalki-Purāṇ a speaks of Him as one whose body is blue like that of the

rain-charged cloud, who with sword in hand rides, as does the rider of the Apocalypse, a white horse swift as the wind, the Cherisher of the people, Destroyer of the race of the Kali-yuga, the source of true religion. And Jayadeva, in his Ode to the Incarnations, addresses Him thus: For the destruction of all the impure thou drawest thy scimitar like a blazing comet. O how tremendous! Oh, Keśava, assuming the body of Kalki; Be victorious, O Hari, Lord of the Universe!” With the satya-yuga a new maha-yuga will commence and the ages will continue to revolve with their rising and descending races until the close of the kalpa or day of Brahma. Then a night of dissolution (pralaya) of equal duration follows, the Lord reposing in yoganidrā (yoga sleep in pralaya) on the Serpent Śeṣ a, the Endless One, till day-break, when the universe is created and the next kalpa follows.

THE SCRIPTURES OF THE AGES

EACH of the Ages has its appropriate Śāstra or Scripture, designed to meet the characteristics and needs of the men who live in them. The Hindu Śāstras are classed into: (1) Śruti, which commonly includes the four Vedas (Ṛ g, Yajur, Sāma, Atharva) and the Upaniṣ ads, the doctrine of which is philosophically exposed in the Vedānta Darśana. (2) Smṛ ti, such as the Dharma Śastra of Manu and other works on family and social duty prescribing for pravṛ ttidharma. (3) The Purāṇ as, of which, according to the Brahma-vaivarta Purāṇ a, there were originally four lakhs, and of which eighteen are now regarded as the principal. (4) The Tantra.

For each of these ages a suitable Śāstra is given. The Veda is the root of all Śāstras (mūla-śāstra). All others are based on it. The Tantra is spoken of as a fifth Veda. Kulluka-Bhatta, the celebrated commentator on Manu, says that Śruti is of two kinds, Vaidik and Tāntrik (vaidiki-tāntriki caiva dvi-vidha śrutihkīrtitā). The various Śāstras, however, are different presentments of śruti appropriate to the humanity of the age for which they are given. Thus the Tantra is that presentment of śruti which is modelled as regards its ritual to meet the characteristics and infirmities of the Kali-yuga. As men

have no longer the capacity, longevity, and moral strength necessary for the application of the Vaidika Karma-kāṇ ḍ a, the Tantra prescribes a special sādhana, or means or practice of its own, for the attainment of that which is the ultimate and common end of all Śāstras. The Kulārṇ ava-Tantra says1 that in the Satya or Kṛ ta age the Śāstra is Śruti (in the sense of the Upaniṣ ads); in Tretā-yuga, Smṛ ti (in the sense of the Dharma-Śāstra and Śrutijīvikā, etc.); in the Dvāpara Yuga, the Purāṇ a; and in the last or Kali-yuga, the Tantra, which should now be followed by all orthodox Hindu worshippers. The Mahānirvāṇ a 2 and other Tantras and Tāntrik works3 lay down the same rule. The Tantra is also said to contain the very core of the Veda to which, it is described to bear the relation of the Parāmātmā to the Jīvātmā. In a similar way, Kulācāra is the central informing life of the gross body called vedācāra, each of the ācāra which follow it up to kaulācāra, being more and more subtle sheaths.

̣ ̣ 1 Kṛ te śrutyukta ācāras Tretāyām smṛ ti-sambhavāh, Dvāpare tu purā- ̣ ̣ ṇ oktam Kālau āgama kevalam.

2 Chapter I, verse 23 et seq. 3 So the Tārā-Pradipa (chap. i) says that in the Kali-yuga the Tāntrika and not the Vaidika-Dharma is to be followed (see as to the Śāstras, my Introduction to “Principles of Tantra”).

THE HUMAN BODY

THE human body is Brahma-pura, the city of Brahman. Īśvara Himself enters into the universe as jīva. Wherefore the mahā-vākya “That thou art” means that the ego (which is regarded as jīva only from the standpoint of an upādhi) is Brahman.

THE FIVE SHEATHS

In the body there are five kośas or sheaths—annamaya, prāṇ a-maya, mano-maya, vijnāna-maya, ānandamaya, or the physical and vital bodies, the two mental bodies, and the body of bliss. In the first the Lord is self-conscious as being dark or fair, short or tall, old or youthful. In the vital body He feels alive, hungry, and thirsty. In the mental bodies He thinks and understands. And in the body of bliss He resides in happiness. Thus garmented with the five garments, the Lord, though all-pervading, appears as though He were limited by them.

ANNA-MAYA KOŚA

In the material body, which is called the “sheath of food” (anna-maya kośa), reign the elements earth, water,

and fire, which are those presiding in the lower Cakras, the Mūlādhārā, Svādhiṣ ṭ hānā and Maṇ i-pūra centres. The two former produce food and drink, which is assimilated by the fire of digestion, and converted into the body of food. The indriyas are both the faculty and organs of sense. There are in this body the material organs, as distinguished from the faculty of sense. In the gross body (śarīra-kośa) there are six external kośas—viz., hair, blood, flesh,1 which come from the mother, and bone, muscle, marrow, from the father. The organs of sense (indriya) are of two kinds—viz.: jnānendriyas or organs of sensation, through which knowledge of the external world is obtained (ear, skin, eyes, tongue, nose); and karmendriya or organs of action, mouth, arms, legs, anus, penis, the functions of which are speech, holding, walking, excretion, and procreation.

PRĀṆ A-MAYA KOŚA

The second sheath is the prāṇ a-maya-kośa, or sheath of “breath” (prāṇ a), which manifests itself in air and ether, the presiding elements in the Anāhata and Viśuddha-cakras.

There are ten vāyus (airs) or inner vital forces of which the first five 2 are the principal—namely, the sapphire prāṇ a; apāna the colour of an evening cloud; the silver vyāna; udāna, the colour of fire; and the milky samāna. These are all aspects of the action of the one Prāṇ a-devata. Kuṇ ḍ alinī is the Mother of prāṇ a, which

̣ 1 The Prapānca-Sara (chap. ii) gives śukla (semen) instead of māmsa (flesh). 2 See Sārada-tilaka. The Minor vāyus are nāga, kūrma, kṛ karā, deva- ̣ datta, dhanamjayā, producing hiccup, closing and opening eyes, assistance to digestion, yawning, and distension, “which leaves not even the corpse.” She, the Mūla-Prakṛ tī, illumined by the light of the Supreme Ātmā generates. Prāṇ a is vāyu, or the universal force of activity, divided on entering each individual into five-fold function. Specifically considered, prāṇ a is inspiration, which with expiration is from and to a distance of eight and twelve inches respectively. Udāna is the ascending vāyu. Apāna is the downward vāyu, expelling wind, excrement, urine, and semen. The samāna, or collective vāyu, kindles the bodily fire, “conducting equally the food, etc., throughout the body.” Vyāna is the separate vāyu, effecting division and diffusion. These forces cause respiration, excretion, digestion, circulation.

MANO-MAYA, VIJNĀNA AND ANANDA-MAYA KOŚAS

The next two sheaths are the mano-maya and vijnāna kohas. These coustitute the antah-karaṇ a,

which is four-fold-namely, the mind in its two-fold

̣

aspect of buddhi and manas, self-hood (ahamkāra), and

̣

citta.1 The function of the first is doubt, samkalpavikalpātmaka, (uncertainty, certainty); of the second, determination (niscaya-kāriṇ i); of the third (egoity), of the fourth consciousness (abhimana). Manas automatically registers the facts which the senses perceive. Buddhi, on attending to such registration, discriminates, determines, and cognizes the object registered, which is set over and against the subjective self by

̣

Ahamkara. The function of citta is contemplation

(cintā), the faculty 2 whereby the mind in its widest

̣ 1 According to Samkhya, citta is included in buddhi. The above is the Vedantic classification. 2 The most important from the point of view of worship on account of mantra-smaraṇ a, devatā-smaraṇ a, etc. sense raises for itself the subject of its thought and dwells thereon. For whilst buddhi has but three moments in which it is born, exists, and dies, citta endures. The antah-karaṇ a is master of the ten senses, which are the outer doors through which it looks forth upon the external world. The faculties, as opposed to the organs or instruments of sense, reside here. The centres of the powers inherent in the last two sheaths are in the Ājnā Cakra and the region above this and below the sahasrāra lotus. In the latter the Ātmā of the last sheath of bliss resides. The physical or gross body is called sthūla-śarira. The subtle body (sūkṣ maśarīra also called linga śarīra and kāraṇ a-śarīra) comprises ̣ the ten indriyas, manas, ahamkāra, buddhi, and the five functions of prāṇ a. This subtle body contains in itself the cause of rebirth into the gross body when the period of reincarnation arrives.

The ātmā, by its association with the upādhis, has three states of consciousness—namely, the jāgrat, or waking state, when through the sense organs are perceived objects of sense through the operation of manas and buddhi. It is explained in the Īśvara-pratya-bhījnā as follows—“the waking state dear to all is the source of external action through the activity of the senses.” The Jīva is called jāgari—that is, he who takes upon himself the gross body called Viśva. The second is svapna, the dream state, when the sense organs being withdrawn, Ātmā is conscious of mental images generated by the impressions of jāgrat experience. Here manas ceases to record fresh sense impressions, and it and buddhi work on that which manas has registered in the waking state. The explanation of this state is also given in the work last cited. “The state of svapna is the objectification of visions perceived in the mind, due to the perception of idea there latent.” Jīva in the state of svapna is termed taijasa. Its individuality is merged in the subtle body. Hiraṇ ya-garbha is the collective form of these jīvas, as

Vaiśvānara is such form of the jīva in the waking state. The third state is that of suṣ upti, or dreamless sleep, when manas itself is withdrawn, and buddhi, dominated by tamas, preserves only the notion: “Happily I slept; I was not conscious of anything” (Pātanjala-yoga-sūtra). In the macrocosm the upādhi of these states are also called Virāṭ , Hiraṇ yagarbha, and Avyakta. The description of the state of sleep is given in the Śiva-sūtra as that in which there is incapacity of discrimination or illusion. By the saying cited from the Pātanjala-sūtra three modifications of avidyā are indicated—viz., ignorance, egoism, and happiness. Sound sleep is that in which these three exist. The person in that state is termed prājna, his individuality being merged in the causal body (kāraṇ a). Since in the sleeping state the prājna becomes Brahman, he is no longer jīva as before; but the jīva is then not the supreme one (Paramātmā), because the state is associated with avidyā. Hence, because the vehicle in the jīva in the sleeping state is Kāraṇ a, the vehicle of the jīva in the fourth is declared to be mahā-kāraṇ a. Īśvara is the collective form of the prājna jīva.

Beyond suṣ upti is the turīya, and beyond turīya the transcendent fifth state without name. In the fourth state śuddha-vidya is required, and this is the only realistic one for the yogī which he attains through samādhiyoga. Jīva in turīya is merged in the great causal body (mahā-kāraṇ a). The fifth state arises from firmness in the fourth. He who is in this state becomes equal to Śiva, or, more strictly tends to a close equality; for it is only beyond that, that “the spotless one attains the highest equality,” which is unity. Hence even in the fourth and fifth states there is an absence of full perfection which constitutes the Supreme. Bhāskararāyā, in his Commentary on the Lalitā, when pointing out that the Tāntrik theory adds the fourth and fifth states to the first three adopted by the followers of the Upaniṣ ads, says that the latter states are not separately enumerated by them owing to the absence in those two states of the full perfection of Jīva or of Śiva.

NĀDI

It is said that there are 3½ crores of nāḍ is in the human body, of which some are gross and some are subtle. Nāḍ i means a nerve or artery in the ordinary sense; but all the nāḍ is of which the books on Yoga speak are not of this physical character, but are subtle channels of energy. Of these nāḍ is, the principal are fourteen; and of these fourteen, iḍ a, pingalā and suṣ umnā are the chief; and again, of these three, suṣ umnā is the greatest, and to it all others are subordinate. Suṣ umnā is in the hollow of the meru in the cerebro-spinal axis. It extends from the Mūladhara lotus, the Tattvik earth centre,

to the cerebral region. Suṣ umnā is in the form of Fire (vahni-svarūpa), and has within it the vajrininādi in the form of the sun (sūrya-svarūpā). Within the latter is the pale nectar-dropping citrā or citrinī nāḍ ī, which is also called Brahma-nāḍ ī, in the form of the moon (candra-svarūpā). Suṣ umnā is thus triguṇ ā. The various lotuses in the different Cakras of the body (vide post) are all suspended from the citra-nāḍ ī, the cakras being described as knots in the nāḍ ī, which is as thin as the thousandth part of a hair. Outside the meru and on each side of suṣ umnā are the nāḍ īs iḍ ā and pingalā. Iḍ ā is on the left side, and coiling round suṣ umnā, has its exit in the left nostril. Pingalā is on the right, and similarly coiling, enters the right nostril. The suṣ

umnā, interlacing iḍ ā and pingalā and the ājnā-cakra round which they pass, thus form a representation of the caduceus of Mercury. Iḍ ā is of a pale colour, is moonlike (candra-svarūpā), and contains nectar. Pingalā is red, and is sun-like (sūrya-svarūpā), containing “venom,” the fluid of mortality. These three “rivers,” which are united at the ājnā-cakra, flow separately from that point, and for this reason the ājnā-cakra is called mukta triveni. The mūlādhāra is called Yuktā (united) triveni, since it is the meeting-place of the three nāḍ īs which are also called Ganga (Iḍ ā), Yamunā (Pingalā), and Sarasvati (suṣ umnā), after the three sacred rivers of India. The opening at the end of the suṣ umna in the mūlādhāra is called brahma-dvāra, which is closed by the coils of the sleeping Devī Kuṇ ḍ alinī.

CAKRAS

There are six cakras, or dynamic Tattvik centres, in the body—viz., the mūlādhāra, svādhiṣ ṭ hāna, maṇ ipūra, anāhata, viśuddha, and ājñā—which are described in the following notes. Over all these is the thousandpetalled lotus (sahasrāra-padma).

MŪLĀDHĀRA

Mūlādhara is a triangular space in the midmost portion of the body, with the apex turned downwards like a young girl’s yoni. It is described as a red lotus of four petals, situate between the base of the sexual organ and the anus. “Earth” evolved from “water” is the

Tattva of the cakra. On the four petals are the four

̣ ̣ ̣ ̣

golden varnas—“vam,” “śam,” “ṣ am” and “sam.” In the four petals pointed towards the four directions (Īśāna, etc.) are the four forms of bliss—yogānanda (yoga bliss), paramānanda (supreme bliss), sahajānanda (natural bliss), and virānanda (vira bliss). In the centre of this

̣

lotus is Svayambhū-linga, ruddy brown, like the colour of a young leaf. Citriṇ ī-nāḍ ī is figured as a tube, and the opening at its end at the base of the linga is called the door of Brahman (Brahma-dvāra), through which the Devi ascends. The lotus, linga and brahma-dvāra, hang downwards. The Devi Kuṇ ḍ alinī, more subtle than the fibre of the lotus, and luminous as lightning, lies asleep coiled like a serpent around the linga, and closes with Her body the door of Brahman. The Devī has forms in the brahmānda. Her subtlest form in the piṇ ḍ āṇ ḍ a, or body, is called Kuṇ ḍ alinī, a form of Prakṛ ti pervading, supporting, and expressed in the form of the whole universe; “the Glittering Dancer” (as the Śaradatilaka calls Her) “in the lotus-like head of the yogī.” When awakened, it is She who gives birth to the world made of mantra. A red fiery triangle surrounds

̣

svayambhū-linga, and within the triangle is the red Kandarpa-vāyu, or air, of Kāma, or form of the apana vāyu, for here is the seat of creative desire. Outside the triangle is a yellow square, called the pṛ thivi-(earth) maṇ ḍ ala, to which is attached the “eight thunders”

̣

(aṣ ṭ a-vajra). Here is the bīja “lam” and with it pṛ thivi on the back of an elephant. Here also are Brahmā and

Sāvitrī, and the red four-handed Śakti Dākinī.

SVĀDHI Ṣ Ṭ HĀNA

Svādhiṣ ṭ hāna is a six-petalled lotus at the base of the sexual organ, above mūlādhāra and below the navel. Its pericarp is red, and its petals are like lightning.

“Water” evolved from “fire” is the Tattva of this cakra.

̣ ̣ ̣

The varṇ as on the petals are “bam,” “bham,” “mam,”

̣ ̣ ̣

“yam,” “ram,” and “lam.” In the six petals are also the vṛ ttis (states, qualities, functions or inclinations)— namely, praśraya (credulity) a-viśvāsa (suspicion, mistrust), avajnā (disdain), mūrchchā (delusion, or, as some say, disinclination), sarva-nāśa (false knowledge), and krūratā (pitilessness). Within a semicircular space in the pericarp are the Devatā, the dark blue Mahāviṣ ṇ u, Mahālakṣ mī, and Saraswatī. In front is the blue fourhanded Rākinī Śakti, and the bīja of Varuṇ a, Lord of

̣

water or “vam.” Inside the bīja there is the region of Varuṇ a, of the shape of an half-moon, and in it is Varuṇ a himself seated on a white alligator (makara).

MAṆ I-PŪRA

Maṇ i-pūra-cakra is a ten-petalled golden lotus, situate above the last in the region of the navel. “Fire” evolved from “air” is the Tattva of the cakra. The ten

petals are of the colours of a cloud, and on them are the

̣ ̣ ̣ ̣ ̣

blue varṇ as—“dam,” “dham,” “nam,” “tam,” “tham,”

̣ ̣ ̣ ̣

“dam,” “dham,” “nam,” “pam,” “pham” and the ten vṛ ttis (vide ante), namely, lajjā (shame), piśunata (fickleness), īrṣ ā (jealousy), tṛ ṣ ṇ ā (desire), suṣ upti (laziness), viṣ āda (sadness), kaṣ āya (dullness), moha (ignorance), ghṛ ṇ ā

(aversion, disgust), bhaya (fear). Within the pericarp is

̣

the bīja “ram,” and a triangular figure (maṇ ḍ ala) of Agni, Lord of Fire, to each side of which figure are attached three auspicious signs or svastikas. Agni, red, fourhanded, and seated on a ram, is within the figure. In front of him are Rudra and his Śakti Bhadra-kāli. Rudra is of the colour of vermilion, and is old. His body is smeared with ashes. He has three eyes and two hands. With one of these he makes the sign which grants boons and blessings, and with the other that which dispels fear. Near him is the four-armed Lākinī-Śakti of the colour of molten gold (tapta-kāncana), wearing yellow raiments and ornaments. Her mind is maddened with passion (mada-matta-citta). Above the lotus is the abode and region of Śūrya. The solar region drinks the nectar which drops from the region of the Moon.

ANĀHATA

Anāhata-cakra is a deep red lotus of twelve petals, situate above the last and in the region of the heart, which is to be distinguished from the heart-lotus facing upwards of eight petals, spoken of in the text, where the patron deity (Iṣ ṭ a-devatā) is meditated upon. “Air” evolved from “ether” is the Tattva of the former lotus. On the twelve petals are the vermilion varnas—“Kam,” ̣ ̣ ̣ ̣ ̣ ̣ ̣ ̣

“Kham,” “Gam,” “Gham,” “Nam,” “Cam,” “Cham,” "Jam",

̣ ̣ ̣ ̣

“Jham,” “Ñam,” “Ṭ am,” “Ṭ ham,” and the twelve vṛ ttis

(vide ante)—namely, āśa (hope), cinta (care, anxiety),

̣

ceṣ ṭ ā (endeavour), mamatā (sense of mineness), ḍ ambha

̣

(arrogance or hypocrisy), vikalatā (langour), ahamkāra (conceit), viveka (discrimination), lolatā (covetousness), kapaṭ ata (duplicity), vitarka (indecision), anutāpa (regret). A triangular maṇ ḍ ala within the pericarp of this lotus of the lustre of lightning is known as the Trikona Śakti. Within this maṇ ḍ ala is a red bānalinga called Nārāyaṇ a or Hiraṇ yagarbha, and near it Īśvara and his Śakti Bhuvaneśvarī. Īśvara, who is the Overlord of the first three cakras is of the colour of molten gold, and with His two hands grants blessings and dispels fear. Near him is the three-eyed Kākinī-Śakti, lustrous as lightning, with four hands holding the noose and drinking-cup, and making the sign of blessing, and that which dispels fear. She wears a garland of human bones. She is excited, and her heart is softened with

wine. Here, also, are several other Śaktis, such as

̣

Kala-ratri, as also the bīja of air (vāyu) or “yam.” Inside the lotus is a six-cornered smoke-coloured maṇ ḍ ala and the circular region of smoke-coloured Vāyu, who is seated on a black antelope. Here, too, is the embodied ātmā (jīvātmā), like the tapering flame of a lamp.

VIŚUDDHA

Viśuddha-cakra or Bhāratisthāna, abode of the Devī of speech, is above the last and at the lower end of the throat (kaṇ ṭ ha-mala). The Tattva of this cakra is “ether.” The lotus is of a smoky colour, or the colour of

fire seen through smoke. It has sixteen petals, which

̣ ̣ ̣ ̣ ̣ ̣

carry the red vowels—“am,” “ām,” “im,” “īm,” “um,” “ūm,”

̣ ̣ ̣ ̣ ̣ ̣ ̣ ̣

“ṛ m,” “r¯̣ m,” “ḷ m,” “l¯̣ m,” “em,” “aim,” “om,” “am,” “aḥ ”; the seven musical notes (niṣ ada, ṛ ṣ abha, gāndhāra, ṣ adja, madhyama, dhaivata and pañcama): “venom” (in the

̣

eighth petal); the bījas “hum,” “phat,” “vauṣ at,” “vaṣ at,” “svadhā,” “svāhā,” “namah,” and in the sixteenth petal, nectar (amṛ ta). In the pericarp is a triangular region, within which is the androgyne Śiva, known as Ardhanārīśvara. There also are the regions of the full moon

̣

and ether, with its bīja “ham.” The ākāśa-maṇ ḍ ala is transparent and round in shape. Ākāśa himself is here dressed in white, and mounted on a white elephant. He has four hands, which hold the noose (paia), the elephant-hook (aṇ kuśa), and with the other he makes the mudras which grant blessing and dispel fear. Śiva is white, with five faces, three eyes, ten arms, and is dressed in tiger skins. Near Him is the white Śakti Śākini, dressed in yellow raiments, holding in Her four hands the bow, the arrow, the noose, and the hook.

Above the cakra, at the root of the palate (tālumula) is a concealed cakra, called Lalanā and, in some Tantras, Kalā-cakra. It is a red lotus with twelve petals, bearing the following vṛ ttis:—śraddhā (faith), santosha (contentment), aparādha (sense of error), dama (self-command), māna (anger), sneha (affection), śoka (sorrow, grief), kheda (dejection), śuddhatā (purity), arati (detachment), sambhrama (agitation), Urmi (appetite, desire).

ĀJÑĀ

Ājñā-cakra is also called parama-kula and muktatri-venī, since it is from here that the three nāḍ is—Iḍ ā, Pingalā and Suṣ umnā—go their separate ways. It is a two petalled lotus, situate between the two eyebrows. In this cakra there is no gross Tattva, but the subtle Tattva mind is here. Hakārārdha, or half the letter Ha,

̣

is also there. On its petals are the red varṇ as “ham”

̣ ̣

and “kṣ am.” In the pericarp is concealed the bīja “om.” In the two petals and the pericarp there are the three guṇ as—sattva, rajas and tamas. Within the triangular maṇ ḍ ala in the pericarp there is the lustrous (tejō-

maya) linga in the form of the praṇ ava (praṇ avākṛti),

̣

which is called Itara. Para-Śiva in the form of ham sa

̣

(ham sa-rūpa) is also there with his Śakti—Siddha-Kāli. In the three corners of the triangle are Brahma, Viṣ ṇ u, and Maheśvara, respectively. In this cakra there is the white Hākini-Śakti, with six heads and four hands, in which are jñāna-mudra, a skull, a drum (damaru), and a rosary.

SAHASRĀRA PADMA

Above the ājñā-cakra there is another secret cakra called manas-cakra. It is a lotus of six petals, on which are śabda-jñāna, sparśa-jñāna, rūpa-jñāna, āghraṇ opalabhi, rasopabhoga, and svapna, or the faculties of hearing, touch, sight, smell, taste, and sleep, or the absence of these. Above this, again, there is another secret cakra, called Soma-cakra. It is a lotus of sixteen petals, which are also called sixteen Kalas. These Kalas are called kṛpā (mercy), myduta, (gentleness), dhairya (patience, composure), vairāgya (dispassion), dhṛti (constancy), sampat (prosperity), hasya (cheerfulness), romānca (rapture, thrill), vinaya (sense of propriety, humility), dhyāna (meditation), susthiratā (quietitude, restfulness), gambhirya (gravity), udyama (enterprise, effort), akṣ obha (emotionlessness), audarya (magnanimity) and ekāgratā (concentration).

Above this last cakra is “the house without support”