Invoking New Mindsets for Peace – The Kalachakra as a Transformational Practice

by Kathryn Goldman Schuyler,

Alliant International University

What does Tibetan Buddhism have in common with the sociological imagination? One might think very little, since Buddhism is perceived as being focused on the individual. I propose there is much in this ancient Tibetan practice that may be of interest to practicing sociologists. This spring in Toronto,

Canada, I joined many thousands of people from all over the world for the twelve-day Kalachakra Initiation, a unique Buddhist event offered periodically by the Dalai Lama. We studied the nature of the mind, of time and space, and received instruction on how to generate peace within ourselves. Many of us enter

our profession wanting to assist people who are suffering, and we think in terms of social systems and their impact on individuals when we formulate questions and programs. In that regard, I want to share the implications and the 'feel' of the Kalachakra experience, as I believe it has intriguing implications for our field and our thinking.

The story of the ceremony The Kalachakra Initiation has been given since the 11th century and used to be kept relatively secret, because it was felt that if it were to be experienced by people who were unprepared, the contents wouldn't make sense and might be misused. After the Dalai Lama was exiled from

Tibet, he began to offer this teaching to large groups of people, and he has taught it nine times in the west. While most of Buddhist "highest yoga tantra" cannot be experienced without years of prior study, this teaching is offered publicly to all who are interested, so as to help bring peace to the world. The Tibetan term for 'initiation' literally means "giving permission" permission to practice the rituals which one learns in the process and from

which one learns thereafter. The Dalai Lama wrote, "in this era when there is so much social tension on the earth, when the nations of the world are themselves so intensely concerned with competition and efforts to overpower one another—even at the threat of nuclear devastation—it is most urgent for us

to try to develop spiritual wisdom." (2004) The teachings he gave at this ceremony covered both the Kalachakra itself and even older Indian texts that discuss the nature of the self and phenomena, the meaning of emptiness, and the way a person moves from delusion toward enlightenment.

At the beginning of the twelve-day cycle, the site is prepared with special rituals that contact the spirits of the place, to ensure that they will allow the ritual to be given as it should. Then the master (in this case the Dalai Lama) leads several monks in reconstructing a very intricate mandala out of

colored sand that represents the palace of a being named Kalachakra. The monks reconstruct the mandala entirely from memory to create a sand 'painting' of great beauty and incredible detail that is then used in the ceremony itself. Using visualization, participants enter the palace (the mandala) and move

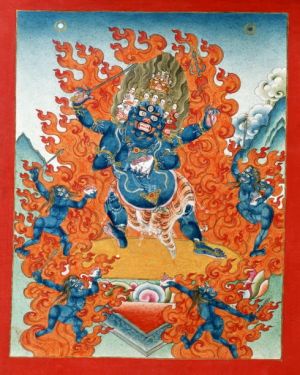

through all of its floors and rooms; in the process, they are reborn as members of a larger family than their physical family - the family of all who have ever used these teachings to understand reality and their place within it. One not only visits the palace; one also imagines becoming Kalachakra (whose

name literally means 'cycles of time'), a 'deity' who lives within it, in eternal embrace with his consort, Vishvamata, the mother of Diversity in all beings and things. A deity in Tibetan Buddhism is not an object of worship. Instead, the term refers to beings that exist in a different way from that of

physical beings. They are mind-created and, in a sense, can exist forever, because they are not born and do not die. There are a great many such deities who represent all different aspects of being and forces that support enlightenment. We view ourselves as deities in order to remember the part of

ourselves that is beyond living and dying and that partakes of the huge complex system that is life in our universe. During the ceremony, each person imagines him or herself becoming Kalachakra and going back and forth between being Kalachakra and being one's ordinary self. The mandala represents both

the palace and the body, mind, and spirit of any being, as well as the entire universe, including representations of the stars, planets, and constellations. According to stories, the palace of Kalachakra is located in a special kingdom known as Shambala, which exists on earth but can only be

seen or visited by those whose hearts and minds are pure. When I was a child, I saw the 1930s movie, "Lost Horizons", modeled on the story of this kingdom hidden by high ice mountains. It left me with compelling memories of wise teachers living in high, inaccessible, snow-covered mountains. Although it was

fiction, it was one of those fictions that I wanted to see become manifest in life.

Implications Over the course of the twelve days, roughly 7,000 people participated, from as far away as Siberia and Taiwan and from all parts of Canada,

the US, and Europe. Most participants seemed to have a depth of spiritual interests and experience, which probably impacted the atmosphere. There was a sense of genuine gemeinschaft: it was always easy to get back and forth from the hotel to the teaching site by the chartered bus, and people were friendly

and easy to talk with at a personal level. As sociologists, we often try to shift people's ways of thinking, from focusing only on the concrete 'things' they see (separate individuals) towards acting as though there are entities we call societies and organizations. We help people perceive the ways that

people's weltanschaungen (world-views) change as the world and the qualities of social life change. We cause people to step outside of the views in which they were socialized as children so that they see a larger view. We help them see that there are societal issues that can best be addressed when they are

understood systemically. Similarly, the Dalai Lama uses the Kalachakra Ceremony to teach people to transcend the mindset and beliefs about themselves in which they were born. The ceremony helps them decide to be born into a global community of people seeking to understand themselves at deeper levels and to

work cooperatively towards peace. This is an approach that believes that outer work in the world starts with inner work but does not end there. It is not what I was taught as a child, that meditating meant gazing at your navel. It instead uses meditation to enable people to become genuinely altruistic and

able to help one another in ways that cause less harm than well-meaning actions often do. What I find important about the way the Dalai Lama teaches about meditation, peace, and ethics is that he emphasizes the importance of developing a sense of universal responsibility and the possibility of creating a nonreligious ethic of peace—and that is what the Kalachakra can help to forge in today's world. Participating in the Kalachakra and other teachings given

by the Dalai Lama opens doors to an understanding of the nature of mind and ourselves that is different from anything in sociology, yet can be seen as being a friendly 'cousin' intellectually. Both encourage us to look beyond physical appearances at the subtle interplay of systems, both appreciate that

our identities are forged through interaction with other beings, and both are nourished by the human desire to make the world a better place for all. What endures through cycles of time? At the end of the ceremony, Dalai Lama carefully removed the symbols that stood for each of the deities who live in

the palace, one by one, by picking up small bits of sand and placing them on a golden plate. With a sweep of his arm, he cut the mandala, and the monks quickly swept the entire brilliantly colored, highly complex design into a small pile of sand, which was then was placed in an urn and thrown into a nearby river, to keep it within the cycle of life. For me, this conclusion epitomized and brought together the entire experience. The moment reminded me of how I

felt when we scattered my mother's ashes to the wind and the earth. At that moment, I had felt that she was free, and that she was home where she wanted to be. I had not expected to feel that, but I did. The sweeping away of the mandala that had been so carefully crafted for days was like a speeded-up

microcosm of our lives: We work carefully to create things (institutions, art, cities, cultures), and then they gradually fall apart. Here, both the creation and the destruction took days instead of years, decades, or centuries. But the process is the same, from the perspective of cycles of time (which

is the literal meaning of the word 'Kalachakra'.) The question raised by all of this is: What remains? What can we create that endures though all of these cycles? And how can we genuinely help the individuals living on our planet today and ease their suffering? My mother taught me the phrase known to

many of us, that the road to hell is paved with good intentions. What are the actions that can help individuals, tribes, religions, and nations to see beyond their own self-interests toward something larger than themselves so that we do not continue to take actions "with good intentions" that create a living hell for others?

The Dalai Lama (2004) “Concerning the Kalachakra Initiation,” in Kalachakra for World Peace Programme, Toronto. The most straight-forward introductory book on the Kalachakra Ceremony for those new to it is Barry Bryant’s (1992) The Wheel of Time Sand Mandala, Snow Lion. The most accessible book on Shambala is Edwin Bernbaum’s (1980, 2001) The Way to Shambala, Shambala Publications.