Is there anything there? – the Tibetan Rangtong Shentong debate

Introduction

During my acquaintance with Buddhism I have generally avoided the notion of emptiness, (´sûnyatâ, stong pa nyid), perhaps feeling that it was too conceptually daunting while simultaneously believing a purely intellectual understanding was of little use. However emptiness is such a central idea it has proven impossible to ignore. Firstly, in the teaching I am most familiar with, Dzogchen (rDzogs chen), it is one of the three qualities of the nature of mind, (sems nyid), and of course in this MA program it has pervaded our studies throughout. However, whilst central it has not always been very clear. As I argued in my first essay, I believe there is something elusive, slippery, about the writing on not self that finally leaves the door open on what exactly is absent – what is empty.

Even the translation of anâtman reflects this ambiguity. ‘No self’ suggesting categorically that no essential entity may be found at either the empirical or metaphysical ‘levels’. ‘Not-self’ permitting that while there may be no essential entity in the skandhas, the conditioned dharmas, it is at least possible that beyond them something unconditioned may exist. (Jiang 2006:23) Further more I have also realised that there is enough ambiguity to allow writers to interpret and present the material in such a way that it reflects their personal beliefs.

(For example Garfield 1995:98) While Western academics may strive to overcome this colouring of the material Panditâs in Asia and the Far East have taken the opposite route. They have made their individual understandings into a whole industry of ‘emptiness philosophies’, each vying with the other for the claim of definitive truth. Nowhere is this truer then in Tibet, which has a bewildering array of finely argued positions on exactly what emptiness is. Broadly speaking these deliberations may be reduced to two positions, Rangtong, the ‘self empty’ position and Shentong, the ‘other empty’ position. It is these positions that this essay intends to describe and, anticipating the argument, hopes to suggest are firstly, made possible by the ambiguity of early Buddhism, secondly, are only partially reconcilable and thirdly, that the Shentong position, true or not, is the more ‘archetypally desirable’.

Rangtong and Shentong

The term Shentong, (gzhan stong), emptiness of other, originates definitively with Dolpopa Sherab Gyaltsen, (Dol po pa Shes rab rgyal mtshan), a fourteenth century Sakya (Sa skya) Lama who later joined and much influenced the Jonangpa (Jo nang pa) school of Tibetan Buddhism. Dolpopa and the Jonang school are no longer well known because in the mid seventeenth century the school, and particularly Dolpopa’s teachings, were suppressed by the fifth Dalai Lama, Ngawang Lozang, as a consequence of the political victory of the region of Chang over Tsang and the resultant rise of the Gelugpa (dGe lug pas) school.1. Further more, much subsequent presentation of emptiness has come from writers who have continued the Gelug position on emptiness and the prejudice against Dolpopa and the Jonang tradition. (Williams 1989:107, Hookham 1991:5) Thus most Western Tibetan Buddhist’s today do not know that Dolpopa was amongst the greatest sages in his time and that his Shentong view was taken up by the nineteenth century ecumenical Rimay (Ris med) movement and is today presented in a variant form by many prominent Kagyupa (bKa’ brgyud pa) and Nyingmapa (rNying ma pa) Lamas. (Stearns 2002:77)

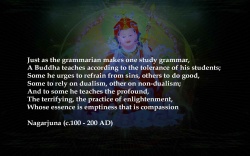

The back ground to the Rangtong/Shentong debate is that Tibet received from India and elsewhere different presentations of emptiness and these differences were taken up and argued with great intensity and often what may seem to us, disproportionate aggression. When Dolpopa enters this debate as a young man, the dominant view is that of Rangtong, emptiness of self-nature, a view that was held by the Mâdhyamikas of particularly the Sakya and Kadampa (bKa’ gdams pa) schools. The Rangtong view is ‘each empty of its own essence’ (rang rang gi ngo bos stong pa), a view presented by Nâgârjuna in his exegesis of the Prajñâpâramitâ Sûtras.

This holds that that the Sarvâstivâda Abidharma does not carry its analysis far enough because it retains the distinction between conditioned and unconditioned dharmas and even implies a kind of self in the conditioned dharmas by conceiving them as irreducible basic ‘units’. By Nâgârjuna’s logic this cannot be so. Because of the truth of dependent origination, (pratîtyasamutpâda), all dharmas are conditioned by their context and so have no discrete ‘self nature’ (bhâva) or ‘inherent existence’. Quite simply; what a dharma is is what conditions it. This is also true for even Nirvâ.na, the unconditioned dharma, without samsâra, Nirvâ.na could not exist. This absence of self nature being synonymous with dependent origination is what is understood as ‘empty of self nature’ and from this we are to understand that there is no ‘Absolute Truth’ as this would imply it possessing an inherent self nature, rather, the absolute truth is the truth of relativity and that there is nothing beyond it. Thus:

Emptiness, then, is an adjectival quality of ‘dharmas’, not a substance that composes them. It is neither a thing nor is it nothingness; rather it refers to reality as incapable of ultimately being pinned down in concepts. (Harvey 1990:99)

Dolpopa does not object to this but he finally believes it does not go far enough. Arriving at Jonang he has something of an epiphany when he sees there many realised practitioners. Subsequently he meets the Karmapa, Rangjung Dorje, a possible source for ‘proto-Shentong’ teachings, (Hookham 1991:150), and then Yonden Gyantso, from whom he receives the transmission of the Kalacakra Tantra. At Jonang he enters retreat and it is during this retreat that the realisation of Shentong occurs – although it is a further five years before he openly teaches it. This story is important because it establishes the origins of Shentong in meditative realisation. As S. H. Hookham (1991:60) repeatedly emphasises, Shentong is a view that arises from faith in the direct knowledge of the nature of mind. Logic cannot reveal it while yoga practice can.

Immediately Dolpopa started teaching he met opposition from Rangtongpas who believed his realisation was non-Buddhist. He taught that there are two expressions of emptiness, the self empty, Rangtong, and the controversial, empty of other, Shentong. These two correspond to the two levels of reality, the relative and the ultimate respectively. While the relative level of conditioned dharmas is empty of self nature, the Rangtong position, the absolute level is only empty of anything relative and conditioned, that is, the ‘empty of other’ Shentong position. Thus for Dolpopa the absolute truth is that there is indeed an Absolute Truth, that there is a true nature of reality (chos nyid, dharmatâ) which is “uncreated and indestructible, non composite and beyond the chains of dependent origination.” (Stearns 2002:82)

Dolpopa connected this knowledge of emptiness to the notion of Buddha Nature found in the Tathâgatagarbha Sûtras. Dolpopa believed the Tathâgatagarbha to be the clear light of the dharmakâya, the buddha-body of reality that is experienced as a “primordial, indestructible and eternal state of great bliss inherently present in all its glory within every human being.” (Stearns 2002:83) The Buddha Nature itself is stainless because it is unconditioned and therefore it is ‘empty of other’, that is, empty of the obscurations of the kle’sa, which are in themselves, empty of ‘self nature’.

What was shocking for those accustomed to the solely Rangtong interpretation was that Dolpopa uses language borrowed from the Mahâyâna context in such a way as to contradict the established hermeneutic. Terms such as Tathâgatagarbha, ‘Buddha Nature’, dharmadâhtu, ‘expanse of reality’, dharmakâya, ‘buddha-body of truth’, were used literally as definitive (nitârtha, nges don) rather than as provisional (neyârtha, drang don) truths. Also terms found in the Lañkâvatâra, Gandavyûha, Añgulimâliya, ‘Srîmâlâ and Mahâparinirvâna Sûtras that could be translated into Tibetan as “self”, “permanent”, “everlasting” and “eternal” were used in a way that suggests no Rangtong interpretation is necessary.

(Stearns 2002:49) Further more Dolpopa also created his own Dharma terms (chos skad) which both reflected his Shentong position and his adaptation of the existing Madhyamaka and Cittamâtra philosophies. This finally found expression in a Yogâcarâ-Madhayamaka synthesis that to this day is the Shentong School of the Mahâmadhyamaka.2. A school, Dolpopa held was founded in the works of the Indian adepts, Nâgârjuna, Asañga, Vasubandhu and Dignâga, whom he believed all held the Shentong view with the Rangtong view contained, as a ‘subsection’, within it.

The ambiguity of Early Buddhism

There is a great deal of scholarly debate concerning the origins of the Shentong view and whether it is even Buddhist. However Hookham (1991:149) argues that:

Since there are such clear Sutra and Shastra hints at a Shentong-type interpretation of Emptiness and Jnana, in Mahayana and also in Pali and other early canons – to extensive to even begin to mention here – there seems little cause to seek the source of Shentong anywhere else than in mainstream Buddhist traditions.

With this in mind, in this section I want to firstly explore some key concepts of ‘early Buddhism’ and see if they provide the seeds for both the Shentong and Rangtong positions. Secondly, I would like to suggest that, despite Buddha’s manifest teaching, there is an implicit leaning towards the Shentong view.

The empty self

While there is no categorical denial of a self, (âtman), in the early Sûtras (Harvey 1995:14.1, Gethin 1998:160), it is clear from most sources that we are not to use this as an invitation to reimport the self through the back door, (for example Harvey 1995:1.50). Thus it is plain, at least according to most readings, that the Buddha’s teaching on not-self, (anâtman), and emptiness are to be understood as affirming that the personality factors, (skandhas), are empty of any permanent, ultimately real, empirical or metaphysical self. This is clearly the precursor of the Madhyamaka understanding of emptiness and the Rangtong view.

Consciousness

In early Buddhism, consciousness, (vijñâna), one of the five personality factors, plays a central role where it both guides and is influenced by the other factors. Later, in the Yogacâra, consciousness is further differentiated. In addition to the initial six types that correspond to the consciousness of the five senses and mind, two additional consciousnesses were added. Manas, the aspect of mind consciousness that unconsciously organises the information flooding in through the first five consciousnesses. And the âlaya-vijñâna, a ‘store house consciousness’ that acts as a kind of ‘holding house’ for karmic seeds that are waiting for secondary causes to enable them to come to fruit. The âlaya may also be subdivided or split further to create a ninth consciousness, the param-âlaya, the ‘beyond consciousness’. This consciousness is non-dual and is “known as the Dharma-dâhtu, the “Dharma realm’, ‘thusness’, equivalent to emptiness and Nirvâ.na.” (Harvey1990:108). Such a definition is capable of being understood retrospectively from both a Rangtong and Shentong perspective but it is highly suggestive that Dolpopa both contrasts and links the terms kun gzhi rnam shes, (âlaya-vijñâna, universal ground consciousness) and kun gzhi ye shes, (âlaya-jñâna, universal ground wisdom). (Sterns 2002:51). He seems here to directly reflect the division of the âlaya into its compounded and more profound, non-compounded aspects. A Shentong view grown in two steps out of early Buddhist soil.

The brightly shining mind

Closely related to the understanding of consciousness is the notion that however unstable the mind, (citta, sems), might be it also has a potential for awakening. This is found in its quality of radiance and purity that may be obscured but not destroyed or damaged. Remove the obscurations and Nirvâ.na is revealed. This idea is immediately familiar to us and is strikingly similar to that of the Tathâgatagarbha – an innate Buddha Nature of timelessly pure untarnishable luminosity. This may again be interpreted retrospectively from either a Rangtong or Shentong perspective but I would suggest that while it does not affirm an inherently existing Absolute Reality it does suggest an intuition of something beyond the personality factors that is not-self in that there is nothing of the empirical personality to be found within it. Intimation, if not a confirmation, of the Shentong view.

Nirvâna

Out of all of the terms we have looked at Nirvâ.na is possibly the most ambiguous. The term ‘Nirvâ.na’ in early Buddhism is used as both a verb and a noun. (Gethin 1998:75, Williams 2000:49) Thus it is both an event and also a specific type of experience. It is the ontological status of the second use that is problematical. Williams (2000:50) says that it is vulnerable to being interpreted as an “Absolute” or a “Reality” which likens it to the concepts of Self (âtman) and Brâhman and even God. This is perilously close to identifying with the eternalist view and deviating through wrong view (d.r.s.til) from the middle way between externalism and nihilism. Williams is so concerned that he argues forcefully for a purely negative interpretation so to avoid this trap. Harvey (1995:1.15) is equally concerned and argues, using a quasi syllogism, that Nirvâ.na may not be used as a synonym for Self. He says firstly, all constructed things, i.e. dharmas, are impermanent, a pain and are not self. Secondly Nirvâ.na is also a dharma – (an unconstructed dharma). Therefore, thirdly, if Nirvâ.na is a dharma and all dharmas are not self it follows that Nirvâ.na is also not self.

However the truth is that various Buddhist schools have used both negative and positive descriptions of Nirvâ.na. These range from the absence of defilement’s, to the not nonexistent, (abhâva), to the real, (dravya), to emptiness, (´sûnyatâ), and non-duality, (advaya). (Gethin 198:78) And that it is these different descriptions that have fuelled the debate as each has seen the other deviating from their own interpretation of the middle way.

Within this spectrum Shentong, as a positive description, occupies a position that leans towards exactly what Williams criticises. It does affirm the Absolute Reality of the Buddha Nature that is realised at Nirvâ.na. However early Buddhism does appear to allow this interpretation. Harvey (1995) also argues that Nirvâ.na is an experience of consciousness once it is no longer conditioned by the skandhas. He says in Nirvâ.na, “Discernment is thus unsupported, unconstructed, infinite and radiant, beyond any worldly phenomenon.”

(Harvey 1995:14.7) Thus consciousness, normally a conditioned dharma when identified with the psychophysical phenomena of the personality factors, may also become unconditioned in the Nirvâ.na state. So how are we to understand this? Awakened consciousness is empty of self but its particular form of emptiness of self seems to be different from when it is subsumed in the ignorance of identification with the skandhas. Thus we have two types of emptiness, the emptiness of self in the skandhas that reveals the absence of an empirical and metaphysical self. And the emptiness of the self in Nirvâ.na that reveals nothing of the empirical self existing within the Nirvâ.na consciousness.

Harvey seems to confirm this view when he tells us that all conditioned dharmas are empty of self because they are impermanent and a source of suffering, while the unconditioned dharma, Nirvâ.na, is empty because it does not “support the feeling of ‘I-ness’”, that is, the impermanent skandhas. (1990:52). This is very similar to the teaching of the modern Kagyu Nyingma Lama, Tulku Urgyen Rinpoche, a Shentong exponent:

All appearances are empty, in that they can be destroyed or extinguished in some way. . . The whole universe vanishes at some point, destroyed by the seven fires and one immense deluge. In this way, all appearances are empty.

Mind is also ultimately empty, but its way of being empty is not the same as appearances. [My italics] Mind can experience anything but it cannot be destroyed. Its original nature is the dharmakaya of all Buddhas. You cannot actually do anything to mind – you can’t change it, wash it away, bury it or burn it. What is truly empty, though, is all the appearances that appear in the mind. (Tulku Urgyen 1999:53)

Finally, while it is inappropriate to retrospectively apply Rangtong and Shentong definitions to early Buddhism, it is none the less possible to see the seeds of both views in the earliest layers of teaching. Yet caution is needed because it is also very easy to project either a Rangtong or Shentong reading onto this material without recognizing one is doing it. The simple exercise of trying to intentionally do both shows how easily interpretations are made. However, this said, I think it needs more interpretation to exclusively support the Rangtong view rather than a Shentong view and therefore a Shentong view comes more naturally. Why this may be so is addressed in the final section.

The relationship of Rangtong and Shentong

Attempting to understand the relationship between Rangtong and Shentong is an enormous undertaking because of the volume and subtlety of the arguments involved. However Williams provides a good summary:

It should be clear that some of the tension between the two approaches can be traced to an opposition between the Madhyamaka view of emptiness as an absence of inherent existence in the object under investigation, and the tathâgatagarbha 3. perspective on emptiness, so influential in Chinese Buddhism including Ch’an, which sees emptiness as the radiant pure mind empty of its conceptual accretions. (Williams 1989:195)

From this we see that although there are two understandings of emptiness, emptiness for both approaches is the central concern. Further more, both approaches also hold that the Buddha delivered his teachings on emptiness in successive waves, which are described within the Mahâyâna tradition as the ‘three turnings of the Wheel of the Dharma’. However the agreement ends at this point because neither approach can agree which of the turnings represents Buddha’s definitive teaching and which his provisional.

The Rangtong view of Prâsangika Madhyamaka, which is now mainly but not exclusively held by the Gelugpas and Sakyapas, holds that the second turning is definitive. Following their reading of Nâgârjuna, everything is empty of self. Tsongkhapa, the founder of the Gelug school and fervent adversary of Dolpopa, sees the third turning, with its more positive description of how things are, as Buddha’s skilful means displaying itself through a teaching designed not to alarm those afraid of emptiness and a way to introduce the Dharma to non-Buddhists who are attached to the Hindu understanding of a self or a soul. However this is a provisional description, which if taken literally, would dangerously imply the existence of a self – which must from any perspective be avoided. Thus the Rangtong interpretation of the Tathâgatagarbha is that it is actually synonymous with dependent origination because it is this that makes it possible for things to change and this includes the ability to fully recognize emptiness, which is to enter Nirvâ.na.

The Shentong view of the Mahâmadhyamika, held largely by the Nyingmapas and Kagyupas, to the contrary, holds that the third turning is the definitive and final teaching. It takes the imbalances in the second and third turnings and sets them in correct relationship to each other. The Rangtong position is not rejected but is none the less seen as too monolithic. The emptiness of Nirvâ.na and the Tathâgatagarbha should be understood on two levels; while it is generally true that Nirvâ.na and sa.msâra are both empty, they are however empty in different ways. Sa..msâra is empty of self nature – just as the Rangtongpas rightly say. But Nirvâ.na is specifically only empty of sa.msâric concepts and entities while being not empty of enlightened qualities. To fail to make this interpretation is to fail to recognize the Buddha’s teaching on the essential difference between the conditioned and unconditioned – a difference that makes Nirvâ.na possible.

A second point of agreement is that both positions believe that having the right view is of the utmost importance because without it enlightenment will be impossible. However the Rangtongpas see in the Shentong view of the Tathâgatagarbha a falling into the wrong view of eternalism that is tantamount to accepting a self. Since the Buddha taught that grasping at a self was the cause of suffering, the Shentong position will only lead to more suffering and not the liberation of Nirvâ.na. The Shentongpas say that if both Nirvâ.na and sa..msâra are empty in the same way – devoid of self existence or intrinsic reality – then this is tantamount to nihilism. This definition of emptiness may describe samsâra but to say it also incorporates Nirvâ.na and Buddha Nature collapses one into the other and does not accord with either the teaching of the earliest Sûtras, Mahâyâna Sûtras or the Tantras.

Lastly Rangtongpas and Shentongpas each have their own view on emptiness and its relationship to ‘intrinsic purity’ – a quality of the Buddha Nature. According to the Rangtong /Gelugpas, when the mind is defiled by the kle’sas, and therefore in its unenlightened state, its potential for awakening is called ‘tathâgatagarbha’, perhaps emphasising its embryonic imagery. When the mind is purified and enlightened this is described as the union of the Buddha’s Essence Body (svâbhâvikakâya) and Wisdom Body (jñânakâya) in his Truth or Reality Body (dharmakâya), which is understood as the Buddha’s mind as a flow of empty existence. From this two things are made apparent.

Firstly that the dharmakaya and emptiness itself are both empty of self and without inherent existence because they too dependently arise from causes and conditions and therefore have no absolute existence in the sense of being an ultimate really existing entity. Secondly, our Buddha Nature is the cause of the dharmakâya – it is not the same as its result in any way other than both being the emptiness of inherent existence. Thus for the Rangtongpas we practice dharma because we must transform and purify the potential of the Buddha Nature into the realisation of how things really are – the dharmakâya.

Conversely the Shentongpas take the Tathâgatagarbha literally as an ultimate reality that possesses inherent existence. It is that in us which is eternal, unchanging and uncreated. Non-dual awareness that is empty of all conditioned dharmas, intrinsically aware and spontaneously compassionate – undivided enlightened qualities. While this may be obscured by defilement’s, the defilement’s do not truly exists and so the path is the recognition of the Tathâgatagarbha as already the dharmakâya – it requires no purification because it is the only one thing that is not conditioned nor arising from causes.4.

From the above, I think it is apparent that while the Rangtong approach precludes the Shentong, the Shentong does not preclude the Rangtong but attempts to colonise it. However this colonisation is unacceptable to the Rangtongpas because it is tantamount to a denial of the essence of their position – a position the Shentongpas could not accept on its own terms. A full description of this colonisation is provided by Hookham (1991:19), she quotes the Nyingma scholar, Kenpo Tsultrim’s ‘Progressive stages of meditation on emptiness’. He says that this progresses through six views: ‘Srâvaka, Cittamâtra, Svâtantrika Madhyamaka and Prâsa’ngika Madhyamaka, all of which are Rangtong in approach and progressively analytical. And lastly Yogacâra-Madhyamaka that is the Shentong approach realised through faith and direct experience.

Obviously such an analysis is highly partisan and open to debate but it does begin to give an insight into the highly nuanced and intricate systems of classification and sub-classification that the Tibetan pondering on emptiness has created. Perhaps finally this is a subject that can never be resolved philosophically because emotionally we need both negative and positive descriptions of reality and liberation from illusion. Each is a valuable and mutually dependent expression of the Buddhist enterprise. Kenpo Tsultrim, this time quoted by Ray (2000:445) takes this view saying that the Rangtong/Shentong debate reflects different temperaments, some more analytic and rational, some more contemplative, however, even though one approach may be preferred over the other it is important to use our investigative intelligence and reason. Finally. I would suggest, that it is impossible to know whether or not the experience of Nirvâ.na, that each approach offers and engenders, is the same or different. Nirvâ.na is at bottom inconceivable and therefore what ever we imagine the Nirvâ.na of either approach to be, that it most surely is not.

Is the Shentong position more archetypally desirable?

Within a tiny decommissioned church, that lays immediately adjacent to a Buddhist Retreat Centre in the depths of Devon, is a board on which petitioning prayers may be left. This board is covered with entreaties, mostly made by Buddhist retreatants, who are making requests, if not to a Christian Father God, then certainly to something that they feel is real and ‘there’.

This is an example of what I believe is an archetypal predisposition towards the Shentong view. That is, people instinctively, intuitively, move towards a faith in a self existing Absolute Reality that is outside of time, unconditioned and a profound source of spiritual refuge and solace. This observation is not to say that this innate inclination ‘proves’ the truth of this belief. My argument here is merely that we emotionally gravitate towards Shentong more easily, not that this makes it necessarily ontologically true.

Archetypes

One way of explaining this phenomenon is to consider it an expression of an archetypal human sensibility to the divine. Here I define an archetype as a shared experience that transcends cultural boundaries. For example, all cultures experience the mother and child relationship. Although each culture and the individuals within it will add something of their own to the ‘basic event’, the basic event – mother and child – remains the same. This is also true of non-biological archetypes. All human societies have spiritual experiences and create ‘religions’ around them that additionally reflect local individuality.

Rudolf Otto (1917) in The Idea of the Holy termed this archetypal apperception of the divine the ‘numinous’, an experience of something “totally other” which is a “higher reality” that has the effect of lifting us beyond the confines of our usual self-concept. C. G. Jung suggested that the archetype behind this was one that he called the ‘Self’. By this he meant, not the psychoanalytic notion of a personal self, but rather a Self, that like the numinous, was both the root of all images of the divine and simultaneously the source of all transpersonal experiences. Put simply, there is something in each of us that hungers for something more real than our personality and this hunger is generated by ourselves from an intuition that such a reality truly exists. I suggest it is this hunger that is attracted to the Shentong view and perhaps is also its origin.

The perennial philosophy

A further reflection of this archetypal predisposition is found in the writing on the perennial philosophy, a collection of ideas that broadly suggest that all spiritual paths are motivated by a shared vision and lead to a common experiential goal. (Huxley 1945, Wilber 1981, 1999, Ferrer 2002). Huxley defines the perennial philosophy as:

The metaphysics that recognizes a divine Reality substantial to the world of things and lives and minds; the psychology that finds in the soul something similar to, or even identical with, divine Reality; the ethic that places man’s final end in the knowledge of the immanent and transcendent Ground of all being. (Huxley 1945, quoted Ferrer 2002:74).

What I wish to emphasise here is that this notion of the perennial philosophy, whether true or not, is in itself an expression of the archetypal predisposition to create ‘spiritual’ systems that envision/evoke experience of an absolute, truly existing reality. Not established through reason but through an immediate intuition that such a reality does exist. As such, while we may not accept the historical reality of the existence of the perennial philosophy (as in fact I do not) we are compelled to accept that the belief in its existence reflects a psychological need for the experience it seeks to articulate. In much the same way as Jung’s concept of the archetype of the Self, the perennial philosophy imagines for us the existence of something we believe is eternal or beyond time, is real, may not be effected by change and is beyond suffering. In short, it is in harmony with the Shentong view. While the perennial philosophy envisions a “Ground of all being”, Dolpopa speaks of “universal ground gnosis” (kun gzhi ye shes). This is not say that the two concepts are the same, (Huxley was actually a neo-Vedantist), nor that either is ontologically true, but simply they both reflect the archetypal/emotional need for an absolute and universal truth.

The difficulty of maintaining a middle way

Buddhism, as a human endeavor, has also struggled with the archetypal predisposition towards a need for a self existent Absolute Reality. In Buddhism’s case, as we have seen, this has largely expressed itself in the conflict between, on the one hand, the philosophic need to establish a middle way between affirming or denying such a reality, and on the other, the human need to make emotionally available the Buddha as a divine ‘figure’ or ‘principle’ once his physical presence or close historical proximity had gone.

I suggest this conflict may have contributed to the many contradictions that exist in Buddhist teachings. Mahâyâna Buddhism’ attempts to reconcile these differences through its notion of the successive turnings of the ‘Wheel of the Dharma’. However this device in itself has created as many problems as it has solved because there is no universal agreement – as we have seen – on how to hierarchally arrange the teachings in terms of provisional and definitive truth. Perhaps a different approach, one not found in Buddhism as far as I know, would be to simply acknowledge that our different psychological needs have lead us to plant in the Buddha’s mouth truths that answer these needs. One such need has clearly been for the existence of an Absolute Reality that we believe truly exists. Something real and beyond our self that we feel we can depend upon and identify with. To achieve this in the Buddhist context is problematical, as it requires that we circumvent Buddha’s own teaching that the skandhas are not-self and much later, Nâgârjuna’s explication of the Prajñâpâramitâ Sûtras presentation of emptiness. Any challenge to these teachings that has seemed to deviate from the middle way, as defined by each, has been criticised for being Vedic and non-Buddhist.

However, despite the sometimes ferocity of such accusations, the urge to identify a truly existing unconditioned Absolute Reality persists. As I have argued above, early Buddhism leaves sufficient ambiguity in it’s teaching for (some of) us to project onto it our archetypal need for an Absolute Reality. And in Mahâyâna Buddhism this again is made possible in, for example, the Tathâgatgarbha Sûtras, Yogacâra philosophy and Shentong itself. I suggest this tenacity is driven by an ‘archetypal intent’, a force of nature that no amount of philosophising can quiet, and that should it be repressed it generates a ‘frustration of archetypal intent’ that signals itself firstly through a vague disquiet and finally in mental ill health. (Stevens 1982:110) In the face of this primitive instinctual juggernaut all Buddhist philosophic concerns about deviating from the middle way are swept aside by ingenious reinterpretation, ignoring them or simply being unaware of their existence. What has made the ‘Shentong spirit’ so resilient in the face of so much intellectual hostility is that it accords with the intuition of the heart. That part of us that circumambulates Stûpas, makes impromptu shrines and shivers with spiritual awe when in the presence of the numinous.

Conclusion

This essay has not been an attempt to fully explore either the Shentong/Rangtong debate or the panoply of Mahâyâna philosophy that it arises out of. Instead I have attempted a general introduction to Rangtong and Shentong, given an overview of its principle areas of debate and have also touched on how these ideas have their roots in early Buddhism. Finally I have expressed an idea, on the fringe of the essay through out, that the Shentong view, whether true or not, Buddhist or not, is the more immediately accessible because it is in accord with the way we spontaneously imagine something divine to be, while the Rangtong view – though compelling intellectually – has an emotional dryness to it that perhaps requires a more differentiated and rational palate to fully appreciate.

Notes

1. Hopkins 2007: 11, quoting the unpublished work of Gareth Sparham, suggests that this may have had more to do with the Dalai Lama’s intention to prevent further political fragmentation following a long period of discord in which all parties had suffered. A comforting interpretation.

2. I have found the exact classification of schools very difficult. For example Dolpopa speaks of an ordinary and ultimate Cittamâtra and elsewhere the Yogâcarâ-Madhayamaka synthesis is not always associated with the Shentong view despite Shentongpas using Yogâcarâ-Madhayamaka and Mahâmadhyamaka as terms for the school holding the Shentong view.

3. Even the spelling of the term Tathâgatagarbha is affected by whether we adopt the Rangtong or Shentong view. Williams is/was, I suspect, a Rangtongpa, and so must not imply that the Tathâgatagarbha is a ‘ truly established’ Absolute Reality by denoting it with a capital T.

4. An interesting fact here is that later representations of Shentong do not agree with Dolpopa on the principle by which awakening is achieved. Dzogchen’s belief that it is possible to rest in the ‘nature of mind’ directly is in disagreement with Dolpopa’s belief that awakening may not be achieved in this way but rather requires the transformation of the subtle energy body. (Stearns 1999:98)

Bibliography

Chopel, Gendun 2005 An Ornament of the Thought of Nagajuna Clarifying the Core of Madhayamaka Shang Shung Edizioni

Conze E. 1995 Buddhist Texts Through the Ages Oxford, One World

Ferrer, Jorge N. 2002 Rivisioning Transpersonal Psychology SUNY

Garfield, Jay L. 1995 The Fundamental Wisdom of the Middle Way Oxford University Press, New York, Oxford

Gethin R. 1998 The Foundations of Buddhism Oxford & New York, Oxford University Press

Gimello, Robert M. and Gregory Peter N. Ed. 1983 Studies in Ch’an and Hua-yen University of Hawaii, Honolulu

Harvey P. 1990 An Introduction To Buddhism Cambridge, Cambridge University Press

Harvey P. 1995 The Selfless Mind London and New York, Routledge

Harvey P. BUDM 4 Session Notes University of Sunderland

Hookham, S. K. 1991 The Buddha Within SUNY

Hopkins, Jeffrey1999 Emptiness in the Mind Only School of Buddhism University of California press, Berkeley, Los Angeles, London

Hopkins, Jeffrey 2006 Mountain Doctrine, Tibet’s Fundamental Treatise on Other-Emptiness and the Buddha Matrix Snow Lion Publications, Ithaca, New York, Boulder, Colorado

Hopins, Jeffrey 2007 The Essence of Other-Emptiness by Taranatha Snow lion Publications, Ithaca, New York, Boulder, Colorado

Jiang, Tao 2006 Contexts and Dialogue, Yogacara Buddhism and Modern Psychology on the Subliminal Mind University of Hawaii, Honolulu.

Kochumuttom, Thomas A. 1982 The Buddhist Doctrine of Experience Motilal Banarsidass Publishers, Private Limited Delhi

Manjusrimitra Trans. Norbu, Namkhai and Lipman, Kennard 2001 Primordial Experience -an introduction to rDzogs-chen meditation Shambhala, Boston and London

Nagao, Gadjin M. 1991 Madhayamaka and Yogacara State University of New Tork Press, Albany

Ray, Reginald A. 2002 Indestructible Truth, the Living Spirituality of Tibetan Buddhism Shambhala, Boston and London

Ray, Reginald A. 2002 The Secret of the Vajra World, the Tantric Buddhism of Tibet Shambhala, Boston and London

Reynolds, John Myrdhin 2005 The Oral Tradition from Zhang-Zhung Vajra Publications, Thamel, Kathmandu

Reynolds, John Myrdhin 2007. Private correspondence.

Sharma, T. R. 1994 Introduction to Buddhist Philosophy, Vijanavada and Madhyamika Eastern Book Linkers, Delhi India

Stearns, Cyrus 1999 The Buddha of Dolpo, A study of the Life and Thought of the Tibetan Master Dolpopa Sherab Gyaltsen Motilal Banarsidass Publishers, Private Limited Delhi

Stevens, A. 1982 Archetype, a natural history of the self. Routledge and Kegan Paul. London and Henley

Tulku Urgyen Rinpoche 1999 As It Is vol.1 Rangjang Yeshe, Boudhanath, Hong Kong & Nasby

Wilber, Kenneth 1981 Up From Eden, A Transpersonal View of Human Evolution Quest Books, Wheaton, Il, USA/Adyar, Madras, India

Wilber, Kenneth 1999 One Taste Shambhala, Boston and London

Williams, Paul 1989 Mahâyâna Buddhism, the doctrinal foundations Routledge, London and New York

Williams, Paul and Tribe, Antony 2000 Buddhist Thought- A complete introduction to the Indian Traditions Routledge, London and New York

Tags: Aldus Huxley, archetype, Buddha Nature, C.G. Jung, Consciousness, Dolpopa Sherab Gyaltsen, Dzogchen, Emptiness, Fifth Dalai Lama, Gaia House, Madhyamaka, middle way, Nâgâjuna, Nirvâ.na, other empty, perennial philosophy, Rangton & Shentong, self empty, Shunyata, Tathâgatagarbha Sûtras, The brightly shining mind, The empty self

This entry was posted on Thursday, September 22nd, 2011 and is filed under Uncategorized. You can follow any responses to this entry through the RSS 2.0 feed. You can leave a response, or trackback from your own site.

Leave a Reply

Name (required)

Mail (will not be published) (required)

Website

Articles

Book Review: Tibet, a History

Buddist Holy Wars

Do Fish See Water? Emotional currents in Buddhist evolution

Extract: Nothing To Lose, Psychotherapy, Buddhism and Living Life.

Have I experienced rigpa?

Is there anything there? – the Tibetan Rangtong Shentong debate

Mindfulness, Psyche and Soma.

On tradition and scholarship, two rivers and one sea

Shall we trance?

The Buddhist path very, very succinctly.

The Jung – Hisamatsu Conversation May 16, 1958: Further Commentary

The Nirvana Debate – Joseph Goldstein extract.

Unexpected bedfellows, analytical and transpersonal psychotherapy.

With Buddha in Mind, mindfulness based psychotherapy in practice.