James Carter. Heart of Buddha, Heart of China: The Life of Tanxu, a Twentieth-Century Monk.

James Carter’s Heart of Buddha, Heart of China: The Life of Tanxu, a Twentieth-Century Monk is focused, as the subtitle suggests, on the life of the prominent Republican-era master Tanxu 倓虛 (1875-1963; not to be confused with his more famous contemporary Taixu 太虛). Yet it is not a conventional biography, nor is it an entry in the “life and thought” genre once so common in the study of Chinese Buddhism. Rather it is what Carter terms a “micro-history,” an attempt to reveal the historical forces of an era as they intersect in the life of an individual. Carter proceeds by tracing the course of Tanxu’s life, enriching it with a thick description not only of the “great events” but also of the details and textures of social custom and everyday life. As a historian of China, Carter’s core concern is not with Buddhism as such but with its role in certain nationalist projects in the foreign concessions (extraterritorial micro-colonies extorted by imperial powers from the weakened Chinese state). His aim is to enrich our understanding of Chinese nationalism with the inclusion of religiously based contributions such as Tanxu’s and to cast the currents and developments of the day in the more immediate light of one person’s experience.

As explained in the prologue, Carter was led to this project and his methodological approach by a serendipitous encounter with living memory. Originally interested in writing a more conventional monograph on the Buddhist contribution to Chinese nationalism through the medium of architecture, Carter was offered an entrée into the life of Tanxu through an unexpected opportunity to meet with one of his disciples, Lok To 樂都 of the Young Men’s Buddhist Association in New York. This led Carter to shift his focus to Tanxu. In addition to conducting interviews with Lok To and others, Carter traced Tanxu’s peregrinations through China guided by Tanxu’s memoir, Carter’s primary written source. Carter’s tone in the prologue is quite personal as he provides brief vignettes of his travels and encounters and also describes his methodological discomfort over his feelings of “intimacy” with his subject as well as with the presence of the miraculous in Tanxu’s recollections. This more personal voice returns in the epilogue in which he revisits the key themes illustrated by Tanxu’s life and relates the unfortunate end of his relationship with Lok To and his group, who feared that the explicit connection he drew between Tanxu and politics would hamper their renewed activity in the People’s Republic.

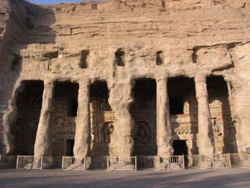

In ten core chapters, Carter traces Tanxu’s life, augmenting the narrative throughout with explanations of his historical and cultural context. Carter devotes the first two chapters to his secular life, for unlike many major monastics of his day Tanxu did not become a monastic until well into middle age. Born near Tianjin and buffeted from his youth by the wars and unrest of his time, he eventually settled in Yingkou 營口 where he raised a family and became a rather successful practitioner of Chinese medicine and fortune telling. At this time he also became deeply concerned with both nationalism and Buddhism. Convinced that China’s survival could be secured only through religious revival, he abandoned his family to become a monk. He traveled south to study under the Tiantai master Dixian 諦閑 at his seminary in Ningbo 寧波, but left after just a few years in order to begin his public life (chapter 3). After an attempt to reconcile with the family he abandoned and a brief stint of famine relief (chapter 4), Tanxu embarked on the work for which he is best known, reviving Buddhism in northern China by establishing and restoring a series of temples across the region in Yingkou (chapter 5), Harbin 哈爾濱 and Changchun 長春 (chapter 6), Xi’an 西安 (chapter 7), and Qingdao 青島 (chapter 8). These activities were what initially sparked Carter’s interest in Tanxu and these chapters are the richest and most interesting of the book. Each of these cities, with the exception of Xi’an, bore the impress of imperial powers due to their history as foreign concessions. In this context, the establishment of a monastery meant not only the creation of infrastructure for the revival of the religion but also the erection of a visible symbol of Chinese identity. The Japanese invasion of 1937 left Tanxu in occupied territory. Though he did not “collaborate” with the new regime in Carter’s estimation, he did reach an “accommodation” that allowed him to continue his activities (chapter 9). Anticipating Communist victory in the civil war that followed the Japanese defeat, Tanxu fled to Hong Kong where he played a leading role in establishing Buddhism in the colony until his death in 1965 (chapter 10).

Carter assembles his microhistory from an abundance of revealing details, some drawn from Tanxu’s memoir or the recollections of his descendants, others drawn from the historiography of the period. The results are often vivid and illuminating. The account of the establishment of Paradise Temple (Jile si 極樂寺) in Harbin is among the strongest examples. A former Russian concession, the city had no Buddhist monastery prior to Tanxu’s arrival. Tanxu sought not merely to establish a beachhead for Buddhism but also to inscribe a Chinese identity at the heart of the city by locating his new temple so as to compete with the local landmarks of foreign architecture. Pursuing these intersecting projects involved negotiating with different constituencies: officials eager for an emblem of Chinese culture; the Christian head of the powerful railroad administration; and local laity who hoped for a more open, informal institution than what Tanxu’s strict, orthodox vision allowed. Carter paints a picture, in short, of religion and nationalism at their most concrete and local. At the same time, he speaks to broader issues, for Carter argues that Tanxu’s project represents a form of nationalism founded on tradition that is still comparatively neglected in the study of Chinese nationalism. Carter’s account is similarly rich in a number of other topics, from the perils of bandits to the plight of a woman abandoned by her husband.

His footing is less sure, however, in dealing with issues of Buddhist doctrine, such as emptiness and the Buddhist view of materiality. He addresses the doctrine explicitly in the final chapter in a discussion of the Heart Sutra. Apparently due to Tanxu’s rather abstruse commentary translated by Lok To’s Sutra Translation Committee of the United States and Canada, he identifies it with the non-materiality of functions such as sight, if I read him correctly, and understands it to be identical to form insofar as they are both alike in having arisen from causes and conditions. Although this does not hinder Carter’s central points, this identification of emptiness with non-materiality does lead him to see materiality as problematic in itself for Buddhism and as an impediment to be transcended in almost Gnostic fashion. This renders Tanxu’s work in the service of nationalism, temple construction, and famine relief appear oddly paradoxical.

The approach adopted by Carter, while often illuminating, is not without inherent limitations. Tanxu, for Carter, is “a means to the end of understanding China’s recent history” (p. 2). As a result, though Tanxu is the central figure throughout the narrative, he is only seldom an object of consideration in his own right. For the reader who does have an intrinsic interest in modern Chinese Buddhism, this can be frustrating at times. This is exemplified by the issue of Tanxu’s rise to prominence. Carter first refers to Tanxu as prominent on page 104. Yet it is not at all clear how the relatively junior monk--at this point, a seminary dropout who had done a bit of relief work--had achieved this prominence. Did he have some signature idea? A particular skill in preaching? A special charisma based on cultivation? A degree of inattention to some aspects of Tanxu’s uniqueness is understandable as Carter primarily wishes to use Tanxu to illustrate larger issues. Yet the paradoxical result is that the man at the heart of his book remains somewhat enigmatic.

In conclusion, Heart of Buddha, Heart of China enriches our understanding of Chinese nationalism and brings the great events and issues of the day into immediate focus through the lens of an individual life. For scholars of Republican China it poses a challenge to further consider the important role that religion frequently played in Chinese nationalism. For scholars of modern Buddhism, it offers an introduction to a significant figure almost unknown in English-language scholarship. More important, it suggests the possibilities that micro-history might offer, especially to the study of modern Buddhism. For the modern period, the resources are available to draw rich portraits of Buddhism on the ground through tight focus on particular individuals, localities, or institutions. Hopefully, Carter’s work will encourage others to exploit these opportunities. Finally, despite the issues with the treatment of Buddhist doctrine, teachers who may be considering offering a course on modern Chinese religion, or specifically Buddhism, will find Heart of Buddha, Heart of China a useful book with which to set the stage, as the thorough contextualization provides an accessible introduction both to the particularities of Chinese religious culture and to the challenges it faced in the twentieth century.

Source

Justin Ritzinger. Review of Carter, James, Heart of Buddha, Heart of China: The Life of Tanxu, a Twentieth-Century Monk.H-Buddhism, H-Net Reviews.August, 2011.

h-net.org/reviews