Jizō Bosatsu (Bodhisattva)

Origin = India / China. Savior from Hell's Torments.

Master of Six Realms of Desire & Karmic Rebirth (Reincarnation).

Patron of Children, Expectant Mothers, Firemen, Travelers, Pilgrims, Aborted / Miscarried Babies. Also guardian of children in limbo.

Affectionately known in Japan as O-Jizō-Sama お地蔵様 or Jizō-san.

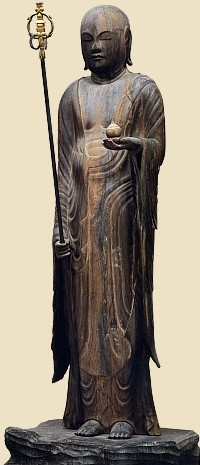

Jizō is the only Bodhisattva portrayed as a monk -- shaven head, no adornments, no royal attire, nearly always dressed in the simple robe (kesa) of a monk. A halo often surrounds the head. Jizō's customary symbols are the shakujō 錫杖 (six-ring staff) and the hōjunotama 宝珠の玉 (wish-granting jewel). When Jizō shakes the staff, it awakens us from our delusions, to help us break free of the six states of rebirth and achieve enlightenment. The jewel (Skt. = Cintamani) signifies Jizō's bestowal of blessings on all who suffer, for the jewel grants wishes, pacifies desires, and brings clear understanding of the Dharma (Buddhist law).

One of the most beloved of all Japanese divinities, Jizō works to ease the suffering and shorten the sentence of those serving time in hell, to deliver the faithful into Amida's western paradise (where inhabitants are no longer trapped in the six states of desire and karmic rebirth), and to answer the prayers of the living for health, success, children, and all manner of mundane petitions. In modern Japan, Jizō is a savior par excellence, a friend to all, never frightening even to children, and his/her many manifestations -- often cute and cartoon-like in contemporary times -- incorporate Taoist, Buddhist, and Shintō elements.

Jizō is a Bodhisattva (Jp. Bosatsu), one who achieves enlightenment but postpones Buddhahood until all can be saved. Jizō is often translated as Womb of the Earth, for JI 地 means earth, while ZŌ 蔵 means womb. But ZŌ can also be translated with equal correctness as "store house" or "repository of treasure" -- thus Jizō is often translated as Earth Store or Earth Treasury. Jizō embodies supreme spiritual optimism, compassion, and universal salvation, all hallmarks of Mahayana Buddhism.

This deity appears in numerous Mahayana texts. One of the most widely known is the Sūtra of the Fundamental Vows of Jizō Bodhisattva (Jp. = Jizō Bosatsu Hongan Kyō 地藏菩薩本願経), in which Jizō vows to remain among us doing good works and to help and instruct all those spinning endlessly in the six realms of suffering, especially the souls of the departed who are undergoing judgment by the Ten Kings of Hell (thus explaining why Jizō statues are commonly found in Japanese graveyards). Jizō promises to unceasingly fulfill these tasks in the eons-long interval between the death of the Historical Buddha and the arrival of Miroku Buddha (the Future Buddha). Miroku is scheduled to arrive, according to Japan's Shingon 真言 sect of Esoteric Buddhism (Mikkyō 密教), about 5.6 billion years from now, to bestow universal salvation on all beings.

Jizō appears in many different forms to alleviate the suffering of the living and the dead. In modern Japan, Jizō is popularly venerated as the guardian of unborn, aborted, miscarried, and stillborn babies (Mizuko Jizō). These roles were not assigned to Jizō in earlier Buddhist traditions from mainland Asia; they are instead modern adaptations unique to Japan. At the same time, Jizō serves his/her customary and traditional roles as patron saint of expectant mothers, women in labor, children, firemen, travelers, pilgrims, and the protector of all beings caught in the six realms of transmigration. Jizō is also one of the 13 Deities 十三仏 (Jūsanbutsu) of the Shingon Sect of Esoteric Buddhism in Japan. In this role, Jizō presides over the memorial service held on the 35th day following one's death. In the mandala of Japan's esoteric sects, Jizō appears as the central figure in the Jizō-in 地蔵院 section of the Womb World Mandala. In the Diamond World Mandala, Jizō appears as Kongōdō Bosatsu 金剛幢 (one of the 16 Great Bodhisattva).

Jizō is also, like Kannon (the God/Goddess of Mercy), one of Amida Buddha's main attendants and, like Kannon, is one of the most popular modern deities in Japan's Amida Pure Land (Jōdo 浄土) sects. The two share many overlapping functions -- both protect the Six Realms of Karmic Rebirth (the Six Jizō, the Six Kannon), both are patrons of motherhood & children (Koyasu Jizō, Koyasu Kannon), and both protect the souls of aborted children (Mizuko Jizō, Mizuko Kannon). In some scriptures, they even share the same Ennichi 縁日 (Holy Day). The 18th day of each month is considered Kannon's Ennichi. Jizō's Ennichi is generally on the 24th, but at many temples it occurs on the 18th.

Contents

- 1 Jizō's Origins

- 2 Male or Female or Both?

- 3 Why the Red Bib, Hat, Toys?

- 4 JIZŌ'S VARIOUS FORMS IN JAPAN

- 4.1 Aburakake Jizō 油懸地蔵

- 4.2 Agonashi Jizō 腮無地蔵

- 4.3 Ajimi Jizō 嘗試地蔵

- 4.4 Asekaki Jizō 汗かき地蔵

- 4.5 Botamochi Jizō ぼた餅地蔵

- 4.6 Chūji Jizō 忠治地蔵

- 4.7 Doroashi Jizō 泥足地蔵

- 4.8 Hadaka Jizō 裸地蔵

- 4.9 Hanakake Jizō 鼻欠け地蔵 or 鼻欠地蔵

- 4.10 Harahoge Jizō はらほげ地蔵

- 4.11 Hawaii Jizō - Guardian of Fishermen and Swimmers

- 4.12 Higiri Jizō 日限地蔵

- 4.13 Hitaki (Kuro) Jizō 火焚地蔵

- 4.14 Hōroku Jizō ほうろく地蔵

- 4.15 Hōyake Jizō 頬焼地蔵

- 4.16 Jizō Bon 地蔵盆 and Jizō Festival 地蔵祭

- 4.17 Kinomoto Jizō 木之本地蔵

- 4.18 Koyasu Jizō 子安地蔵

- 4.19 Kubifuri Jizō 首振地蔵

- 4.20 Kubikire Jizō 首切れ地蔵

- 4.21 Michibiki Jizō 導き地蔵,Guiding Jizō

- 4.22 Migawari Jizō 身代り地蔵

- 4.23 Miso Jizō みそ地蔵 (Bean Paste Jizō)

- 4.24 Misoname Jizō みそなめ地蔵 (Miso Licking Jizō)

- 4.25 Mizuko Jizō 水子地蔵 & Mizuko Ceremony in Japan

- 4.26 Omokaru Jizō おもかる地蔵尊

- 4.27 Onegai Jizō お願い地蔵

Jizō's Origins

Although of India origin, Kshitigarbha (Jizō) is revered more widely in Japan, Korea, and China than in either India or Tibet. Most scholars generally consider Jizō-related texts to be products of China rather than India, followed later by Japanese renditions and additions. Jizō's earliest association is with Prthvi (Prithvi), a Hindu goddess who personifies the earth and is associated with fertility. In the VEDAS, she is celebrated as the mother of all creatures and the consort of the sky. This association with the sky is very important, for many centuries later, in China, Jizō Bodhisattva (lit. Earth Repository) was paired with Kokūzō Bodhisattva (lit. Space Repository), with the two representing the blessings of earth and space respectively. This pairing is now almost entirely forgotten in both China and Japan. But the pairing lends strong support to Jizō's early association with the Hindu goddess Prthvi. The strongest support for the Prithvi/Jizō link, however, is the Jizō Bosatsu Sūtra (Jp. = 地蔵菩薩本願経), a 7th-century Chinese translation from Sanskrit, in which Prthivi vows to use all her miraculous powers to protect Jizō devotees.

When and how Jizō was introduced to China is unknown, but from the earliest extant texts (7th century), Jizō is already closely associated with the earth and with the Lord of Death (Skt. = Yama, Chn. = Yanmo Wang 閻魔王, Jp. = Emma-ō). Only later, in China's late Sung dynasty (960–1279), does Jizō become associated with the Taoist Ten Kings of Hell and appear in Chinese artwork surrounded by the ten. In Japan, Jizō first appears in records of the Nara Period (710 to 794 AD), and then spreads throughout Japan via the Tendai and Shingon sects. According to an old legend, the first Jizō statue was brought to Japan from China and installed at Tachibanadera 橘寺 during the reign of Emperor Shōmu 聖武 (reigned 724-49), but was later moved to Hōryūji 法隆寺 Temple in Nara.

In Japan, Jizō appears first in the Ten Cakras Sutra in the Nara period (now a treasure held by the Nara National Museum), but the height of Jizō's early popularity was during the late Heian era (794 to 1192 AD) when the rise of the Jōdo Sect 浄土 (Pure Land Sect devoted to Amida Nyorai) intensified fears about hell in the afterlife (see Age of Mappo). Due to Jizō's association with the realm of death and suffering souls, Jizō is also closely associated with Amida Nyorai and with Amida's heavenly western paradise, where true believers may seek enlightenment and avoid the torments of hell. In traditional artwork, Jizō is the only Bodhisattva commonly portrayed as a monk. Although the origins of this iconography are unclear, some scholars believe Jizō's depiction as a priest stems from a 7th-century Korean monk named Gin Chau Jue who resided for 75 years at Chiu-hua-shan in China (present day Anhui Province) and who was considered an incarnation of Jizō. When the monk died in 728 (at the age of 99), legend contents that his body did not decay, and was subsequently gilded over and venerated as an emanation of Jizō.

The Jizō cult in Japan incorporates many of the traditional characteristics of Jizō veneration in China, but the Japanese developed their own distinct variants from the Kamakura period onward, including (1) Jizō's close association with the Lotus Sutra; (2) Jizō serving the same functions and roles as Kannon Bodhisattva; (3) Jizō's very close association with Amida Nyorai and the Pure Land sect; (4) Jizō and the Six Realms and the Ten Kings; (5) Jizō as having the same body as Emma-ō, the King of Hell; (6) Jizō's association with warriors; (7) Jizō appearing as a young child or boy and; (8) many other forms of Jizō unique to Japan. Since the Kamakura period, Jizō worship has attained a tremendous following in Japan, and today Jizō remains one of Japan's most revered deities.

Male or Female or Both?

In Japan today, Jizō Bosatsu and Kannon Bosatsu are two of the most popular Buddhist saviors among the common folk. Like Jizō, Kannon is intimately associated with Amida Nyorai (Buddha), for Kannon is one of Amida's principal attendants. Statues of Kannon, moreover, often include a tiny image (Jp. = Kebutsu 化仏) of Amida in the headdress. Curiously, both Jizō and Kannon underwent a change in identity after arriving in Japan. Kannon is male in the Buddhist traditions of India, Tibet, and Southeast Asia. But in China (less so in Japan), the Kannon is typically portrayed as a female divinity.

In Japan, the male form was initially adopted, and it remains the predominant form in traditional Japanese sculpture and art. But female manifestations of Kannon are nonetheless plentiful in Japan. Indeed, a persistent femininity clings to Kannon imagery in both pre-modern and modern Japan. This holds true in Western nations as well, where Kannon is most commonly known as the "Goddess of Mercy." Conversely, Jizō was initially female, but is now portrayed almost always as male, except, perhaps, when appearing as the Koyasu (Safe Childbirth) Jizō).

Jizō in Female Form

Says The Flammarion Iconographic Guide by Louis Frederic:

- "The Chinese Ksitigarbha Sutra relates that, before becoming a Bodhisattva, Jizō was a young Indian girl of the Brahmin caste so horrified by the torment her late impious mother was suffering in hell that she vowed to save all beings from such torments."

Says Wikipedia: "In the Ksitigarbha Sutra, the Historical Buddha revealed that in past aeons, Ksitigarbha (Jizō) was a Brahman maiden named Sacred Girl. She was deeply troubled when her mother died, because her mother had often been slanderous toward the Triple Jewels (Skt. = Triratna), which refers to the Buddha himself, the Dharma (Buddhist teachings or law), and the Samgha (the Buddhist community of followers). To save her from the great tortures of hell, the young girl sold whatever she had and used the money to buy offerings which she offered daily to the Buddha of her time, known as the Buddha of Flowering Meditation and Enlightenment. She made fervent prayers that her mother be spared the pains of hell and requested the Buddha for help. One day at the temple, while she was pleading for help, she heard the voice of the Buddha advising her to go home immediately and there to sit down and recite his name if she wanted to know where her mother was. She did as she was told and while doing so, her consciousness was transported to one of the Hell Realms where she met a guardian who informed her that, through Sacred Girl's fervent prayers and pious offerings, her mother had accumulated much merit and had therefore already been released from hell and had ascended to heaven. Sacred Girl was greatly relieved and should have been extremely happy, but the sight of the great sufferings of those in the hell she had witnessed so touched her heart that she made a vow to do her best to relieve beings of their sufferings in all her future incarnations (Skt. = kalpas)."

Why the Red Bib, Hat, Toys?

Everywhere in Japan, at busy intersections, at roadsides, in graveyards, in temples, and along hiking trails, one will find statues of Jizō Bosatsu decked in clothing, wearing a red or white cap and bib, adorned with toys, protected by scarfs, or piled high with stones offered by sorrowing parents. Such symbolism is based on numerous early influences, which are presented below:

- According to Japanese folk belief, red is the color for expelling demons and illness. Rituals of spirit quelling were regularly undertaken by the Japanese court during the Asuka Period (522 - 645 AD) and centered on a red-colored fire deity. This early association between demons of disease and the color red was gradually turned upside-down -- proper worship of the disease deity would bring life, but improper worship or neglect would result in death. In later centuries, the Japanese recommended that children with smallpox be clothed in red garments and that those caring for the sick also wear red. The Red-Equals-Sickness symbolism quickly gave way to a new dualism between evil and good, with red embodying both life-destroying and life-creating powers. As a result, the color red was dedicated not only to deities of sickness and demon quelling, but also to deities of healing, fertility, and childbirth. Jizō's traditional roles are to save us from the torments/demons of hell, to bring fertility, to protect children, and to grant longevity -- thus Jizō is often decked in red. For more on Japan's "red" tradition, please see Color Red in Japanese Mythology.

- The tradition of dressing certain Buddhist and Shintō deities in red bibs first reportedly appeared in the Heian era and examples can be found in illustrated handscrolls (emakimono 絵巻物) and in the classic Tale of Genji 源氏物語. Note: I have not yet confirmed these findings.

- Perhaps the greatest influence on Japan's tradition of decking Jizō statues in hats, bibs, scarfs, and toys comes from the Sai no Kawara legend attributed to Japan's Pure Land sects in the 14th and 15th centuries. According to this legend, children who die prematurely are sent to the underworld for judgment -- like all sentient beings, their life is reviewed by the 10 Kings of Hell, judgment is pronounced, and they are reborn into one of six realms of existence. They may be pure souls, but they have not had any chance to build up good karma, and their untimely death caused great sorrow to their parents, and thus, they too, must undergo judgment. They are sent to Sai no Kawara, the riverbed of souls in purgatory, where they are forced to remove their clothes and to pray for salvation by building small stone towers, piling pebble upon pebble, in the hopes of climbing out of limbo into Buddha's paradise. But hell demons, answering to the command of the old hell hag Shozuka no Baba (also called Datsueba), soon arrive and scatter their stones and beat them with iron clubs. But no need to worry, for Jizō comes to the rescue, often hiding them in the sleeves of his robe. Even today, this horrific folklore about hell prompts Japanese parents into action. Says Kondo Takahiro (an independent Buddhist scholar from Yokohama): "They imagine their little babies lingering at the riverbed, unable to cross the river, unable to gain salvation. Japanese parents therefore feel a great need to do something to alleviate their child's suffering, to do something to improve the child's chance of redemption. Thus the great cult of Jizō Bosatsu in Japan. Parents cloth Jizō statues in hopes that Jizō will cloth the dead child in his protection. Small pebbles are piled around the Jizō statue as well, offered by sorrowing parents as a prayer to Jizō to help the suffering soul of their deceased child. Even today, Jizō statues in some places in Japan are covered -- sometimes from top to bottom -- in pebbles placed there by sorrowing parents, who believe that every stone tower they build on earth will help the soul of their dead child in performing his/her penance."

- In the Muromachi period, images of the Life-Prolonging Jizō (Enmei Jizō 延命地蔵) began appearing along with two youthful acolytes-servants known as Shōzen 掌善 (white in color, holding a white lotus, master of good, standing to the left of Jizō), and Shōaku 掌悪 (red in color, holding a vajra club, master of evil, standing to the right of Jizō). These two are seldom represented in artwork, but rather symbolized by white and red cloth attached to many Jizō statues. This Pure-Land symbolism obviously borrowed from similar iconography associated with the esoteric Shingon deity Fudō Myō-ō, who is often accompanied by two youthful acolytes-servants known as the white-skinned Kongara Dōji 矜羯羅童子 (who personifies obedience) and the red-colored Seitaka Dōji 制姙迦童子 (who personifies expedient action). Such iconography was probably of Chinese Taoist origin, but it was subsequently incorporated into Buddhism. The Pure Land sects, for example, believe in two deities of Chinese Taoist providence called Kushōjin 倶生神. These two assist the 10 Kings of Hell during the judgment of deceased souls. The pair reportedly keep a complete record of our behavior from the time of our birth to the time of our death, with one recording only our good behavior and the other only the bad.

- In modern Japan, a red hat, bib, and toys are still often found on Jizō statues, the gifts of a rejoicing parent whose child has been cured of dangerous sickness thanks to Jizō's intervention, or a gift to help the deceased child in the afterlife. These traditional practices are now combined with Japan's modern Mizuko Jizō practices (wherein bereaved parents buy tiny Jizō statues to pray for the soul of their aborted or miscarried children). Adds independent scholar Kondo Takahiro: "Some temples, without doubt, take advantage of this folklore. They tell the traumatized parents 'Your lost child will continue to suffer. Your lost child will never be saved unless you take action to soothe their troubled souls. You must buy statuettes and offer religious services to alleviate their suffering.' In Japan, the Buddhist tendency toward mercy and prolonged mourning means that many grieving parents buy expensive statuettes and pay exorbitant fees for memorial services -- the temples thus prosper from such patronage."

JIZŌ'S VARIOUS FORMS IN JAPAN

Many Japanese, even today, believe Jizō will save them at any time, in any situation, without any conditions or stipulations beyond simple faith. Even those who have already fallen into the pit of hell are promised assistance. Jizō is thus very popular and depicted in countless forms throughout Japan. Many originated in recent centuries and are unique to this island nation (not found elsewhere in Asia). It is no exaggeration to say that nearly all villages and localities have their own beloved Jizō statues, which are frequently given unique names defining their specific salvific functions. Some of Japan's innumerable Jizō emanations (both traditional and modern) include:

Aburakake Jizō 油懸地蔵

Greasy Jizō or Oil-Covered Jizō. There are various manifestations. In the Edo period, at Andōji Machi 安堂寺町 in the center of Osaka, those who suffered from intermittent fever smeared a Jizō statue with oil and prayed to it in the belief Jizō would help them recover. Today, at Saiganji Temple 西岸寺 (a Jodō sect temple) in Kyoto's Fushimi 伏見 district, there is an Aburakake Jizō reportedly dated to the Kamakura period. In olden days, Fushimi was a hub of commerce and trade. Says author Judith Clancy in Exploring Kyoto: On Foot in the Ancient Capital: "Inbound cargo was unloaded on the wharves at Chūshōjima, then carried by porters another two kilometers into Kyoto. One day, an oil vendor from Yamazaki (a place to the southwest of Kyoto known for its sesame oil) was making his way down Aburakake Dōri [lit. = oil-covered street] when he tripped and fell, spilling his precious load. He scooped up what was left and offered it to this wayside Jizō. Thereafter he prospered, and as word spread of his good fortune, others came to pray for success. When they achieved it, they gave thanks by pouring a little bit of oil over the image. Today shopkeepers and businessmen continue the tradition of pouring oil over the glistening 1.7-meter-high image, and offerings of ten-liter cans of oil are stacked inside the hall (page 274)."

Agonashi Jizō 腮無地蔵

Lit. = Jizō without a Jaw. Also known as Shitsu Heiyu 歯痛平癒地蔵 (Jizō who Heals Toothaches). Says Gabi Greve: "In the year 1870, the temple 伴桂寺 at Oki Island 隠岐島 had to close down. The last priest of the temple had been a disciple of the head prist of the Hagi Temple in Osaka, so he gave all his temple treasures to Hagi Temple, including a statue of the "Jizō without a Jaw" reportedly made by Ono no Takamura 小野篁 (802–853), a scholar and poet of Heian Japan. Two years later a special hall was built for the statue, which is now a secret (hibutsu 秘仏) statue and only shown once a year to the public." Gabi continues: "Once upon a time in the city of Kanawa in Omiya town on the island of Oki, there lived a man who had a painful toothache. For three days, he was crying all day long 'my tooth aces, my tooth aces so much!' He could not sleep at night and not eat during the day because of the pain. In the end he pulled out his jaw, threw it away - and died. But then, how wonderful, he was reborn as a Bodhisattva. The pious people of Oki Island then made a wooden statue of Jizō without a chin and prayed to it when they got a toothache. Soon people from far away also came to pray for healing, and as a gift of gratitude placed one NASHI (pear) into a nearby river or lake or the ocean. This is a pun on the word NASHI (pear) and NASHI (without, to not have) -- in this case, to not have a toothache."

Ajimi Jizō 嘗試地蔵

Also read Kokoromi. Also written 嘗試地蔵, 味見地蔵, 毒味地蔵. Lit. = Food Taster for Kōbō Daishi (Kobo Daishi) 弘法大師, the founder of Japan's Shingon Sect 真言 of Esoteric Buddhism 密教 (Mikkyo, Mikkyō). Below text courtesy of site contributor Gabi Greve: "This small statue of Jizō stands in a tiny hall in front of Oku no In 奥の院 on Mount Kōya 高野山, where the spirit of Kōbō Daishi 弘法大師, it is said, resides to this day. Every morning at six and at lunchtime Jizō gets food, prepared by monks in a special kitchen, mostly from food offerings by lay believers. Before modern times, food was brought at four and six in the morning. The food is carried in a special procession on a tray and a bit of each item placed in front of Jizō to taste, making sure that no poisoned food is presented to Kōbō Daishi."

Asekaki Jizō 汗かき地蔵

Sweating Jizō. Excretes white sweat if good things are about to happen, and black sweat when bad things are foreseen. There is also a sweating version of Fudō Myō-ō called Asekaki Fudō 汗かき不動. In the Muromachi period (1392-1568), whenever there was a major fight in the country, this wooden statue of Fudō would drip with sacred sweat 霊汗 and thus became widely revered by warriors. It also became a protector against fires for the town of Edo (modern-day Tokyo).

Daio-Cho Town, Ise-Shima Area, Mie Prefecture

The local Jizo Hall in Daio-cho Town holds one of the three great festivals in the Ise-Shima area, the Festival of the Sweating Jizo. According to local legend, a statue of Jizo was long ago caught in a fishing net off Daio Island. It took three attempts to finally retrieve the statue, as though the statue was resisting capture. The fisherman and villagers decided to build a hall and enshrine the statue there to act as a protective village deity.

Since then, local residents say this Jizo statue excretes white sweat if good things are about to happen, and black sweat when bad things are foreseen. The body of this seated stone statue of Jizo is about three feet in height. According to locals, a beautiful pearl is hidden inside the statue. When people pray to this manifestation of Jizo, some may wipe away Jizo's sweat with a purified paper. This, say believers, will bring answers to their prayers. For more on the legend of the Sweating Jizo, please see the "Izo Engibun," written in 1682 AD by the Buddhist priest Fukuju of Senyuji Temple. The festival of the sweating Jizo is held on February 24th each year.

Kaida-son Village, Nagano Prefecture

In front of the local Genryuu-ji Temple are six statues of Jizo Bosatsu, a grouping found commonly in Japan. The largest statue, the one in the middle, is known locally as the Sweating Jizo. It will sweat black to warn local farmers of a late frost or an upcoming dry spell. Forewarned about impending frost, for example, the villagers will make bonfires in the fields to protect the crops from the cold.

Funo Town, Chiba Prefecture

Located in a special Hall for the Life-Prolonging Jizo (Enmei Jizo). On a woodblock print found here, one can see the people assembling around this Jizo as the center of their worship. Local folk say this Jizo also helps to ensure easy birth and to protect the elderly. In old times, according to the legend, when someone in the village died, the neighbors gathered here to pray, only to witness sweat coming from Jizo's body -- indicating, it is said, Jizo's willingness to assume the pain and sorrow of the people.

Mt. Koya, Sacred Mountain of Shingon Sect

Many people are buried in this sacred area, and gravestones of all types can be found here. Jizo, popularly known as the protector of those serving time in the netherworld, is represented in many forms. One hall that stands near the Oku no In 奥之院 (the innermost temple of the Koyasan Monestary, which houses the tomb of Kobo Daishi) is devoted to the Sweating Jizo, who drips with sweat when taking on the pain and suffering of the people.

Choukou-Ji Temple, Inazawa Village, Aichi Pref.

This Jizo sweats to warn people that something bad is about to happen. Sometimes the villagers come with towels to dry him down, but he just keeps pouring sweat from his head down.

Nakajima-mura Village, Fukushima Prefecture

Famous since the Edo Period as the "Sweating Jizo of the Northern Province" (Ooshuu Asekaki Jizo 奥州汗かき地蔵). The Jizo Hall, where the statue is enshrined, dates from the year 1335.

Hashima, Gifu Prefrefecture

This Jizo does not sweat to warn against bad things, but sweats in the morning when the monks go begging (takuhatsu) for food and contributions.

Botamochi Jizō ぼた餅地蔵

Rice-Ball Jizō. During the spring equinox, people visit cemeteries to clean and maintain family graves. They also pray for their deceased loved ones, burning incense and offering them flowers and food. By tradition, the spirits are said to prefer round food, so botamochi ぼた餅 (round glutinous rice balls covered in bean paste) are offered to them during this period. The treat gets its name from the peony (botan 牡丹), whose round bulbs bloom in spring. The Azuki 小豆 beans used for the sweet red paste (anko 甘煮) are also used symbolically to expel evil spirits. The same type of sweet is eaten during the autumn equinox. It is then called O-Hagi 御萩, since it looks like the bush clover (hagi 萩). Some locations in Japan worship a deity named Botamochi Jizō. A story from the Edo Era (1615-1868) goes like this. At Hōzen-In Temple 宝善院 in Hiratsuka 平塚市 (modern-day Kanagawa Prefecture), the town people even today offer botamochi rice balls to Jizō. In former times, the people of this area were extremely poor and many children died of malnurishment. The temple is home to the graves of many babies and the destitute. One day the poor mothers collected money to build a statue of Jizō, and thereafter they prayed to this statue in the hope their children would at least get one good meal of mochi before dying. Elsewhere, in the courtyard of Chōenji Temple 長延寺 in Ichigaya 市谷 (Tokyo), is a statue of Botamochi Jizō dated to the Meiji Period (1868-1912). It is worshipped by new mothers hoping to get well soon after giving birth. According to local legend, Jizō once appeared here as a young monk and presented botamochi to a poor mother to help her provide milk for her baby.

Chūji Jizō 忠治地蔵

Also known as Kunisada Chūji Jizō. Cures palsy. Related to the famous Japanese "Robin Hood" and gambler named Kunisada Chūji 国定 忠治 (1810-1851), whose real name was Nagaoka Chūjirō 長岡忠次郎. Says Gabi Greve:

- "After his death, legends began to build around this 'noble yakuza' and he became more of a local hero. At the place of his execution, a Jizō statue was errected to pacify his soul. When people offered incense there, their own illness of palsy would heal (since Chūji also suffered from palsy). Or they would win in gambling (like Chūji). Songs were written about Chūji and Mount Akagi and movies were cast with the popular hero."

Doroashi Jizō 泥足地蔵

Muddy-Feet Jizō. In the Heian-era collection of setsuwa 説話 (narratives) called the Hōbutsushū 宝物集, an old woman devotee prayed to her small Jizō statue for a successful rice crop. When she awoke the next morning and walked to her rice field, she found it perfectly cultivated and noticed small footprints going back and forth. She dashed home, and as expected, she found mud on the feet of her tiny Jizō statue.

There are many such tales of Jizō taking the place of peasants to give them some respite from their toils (a type of Migawari or Substitute Jizō). In one story, this time from the Jizō Bosatsu Reigenki (a Heian-Era collection of miraculous stories about Jizō), a sick peasant who is unable to work in the fields is assisted by Jizō. Writes Buddhist scholar De Visser (1876-1930): "A peasant in Izumo, who had always had a firm belief in Jizō, had made a small image of the Bodhisattva. He had placed it in a little shrine on a board in his room, and worshipped it daily. One day a severe illness prevented him from obeying the order of the lord of his district to cultivate the lord's rice fields. According to custom, peasants had to do so gratuitously. Thus all the peasants of the village went out on the day fixed by their lord to work in his service, but the poor man could not go and in despair again and again repeated Jizō's invocation Namu Jizō Dai Bosatsu in his lonely house, his beloved wife just having died from the same disease. On the lord's fields, however, a young Buddhist monk worked in his place and fulfilled his task so well, that the lord gave him a wine cup, which he [the young priest] respectfully raised above his head and disappeared. The lord understood that this priest was a divine person and sent a messenger to the peasant's house, in order to reward him. The astonished man, convinced that this was Jizō's work, opened the shrine and saw the wine cup upon Jizō's head and mud sticking to the statue's feet. Apparently the image itself had been his substitute on the field!"

Another story, which appeared in the 1332 publication Genkō Shakusho, involved a Jizō image at Mt. Kōya (Kōya-san, the present-day headquarters of Japan's Shingon sect of Esoteric Buddhism). In those days, the governor of Shimotsuma was making a pilgrimage to the Jizō Hall (chapel) at Kōya-san, but a torrential river blocked his path. Suddenly a boy priest appeared in a boat and rowed the governor across. When the governor arrived at the Jizō Hall, he asked the head monk about the boy, but the monk had no idea. The governor then visited the chapel and was saying prayers to Jizō when he discovered tiny muddy footprints on the floor, which convinced him that Jizō had helped with the river crossing."

Farmers & Peasants Jizō There are many forms of Jizō in Japan dedicated to the concerns of poor farmers and peasant women. In most cases, these are forms of the Migawari Jizō, or Substitue Jizō, one who substitutes for our suffering, one who vicariously receives our hardship, injuries, and wounds.

- Amagoi Jizō 雨乞い地蔵. Begging the sky for rain.

- Ashi-arai Jizō 足洗い地蔵. Depicted washing feet after helping peasants in the rice paddies.

- Doroashi Jizō 泥足地蔵. Muddy-Feet Jizō. A type of Migawari Jizō.

- Hanatori Jizō 鼻取. Leads horses and cattle. A type of Migawari Jizō

- Hikeshi Jizō 火消し地蔵. Fire-Preventing Jizō. Protects houses and the harvest from fire.

- Mawari Jizō. 回り地蔵 or 廻り地蔵. Protects villages. In the mid-Edo period, a circuit of sites devoted to Jizō was established, and making the circuit was said to bring various benefits from Jizō. Hence the name "Mawari Jizō (mawari means circumambulation). One well-known Mawari Jizō statue is located at Senryūji 泉龍寺, a Sōtō Zen temple located in Komae (present-day Tokyo).

- Migawari Jizō. Helps peasants in their work. Many variations. A type of Migawari Jizō

- Mizuhiki Jizō 水引地蔵. Brings water to the rice paddies. A type of Migawari Jizō

- Tachiyama Jizō 立山地蔵. Takes the place of women peasants so they can rest once a month. A type of Migawari Jizō.

- Taue Jizō 田植地蔵. Helps farmers to plant rice. A type of Migawari Jizō

- Togenuki Jizō. Removes splinters and thorns to reduce the pain of hardworking peasants.

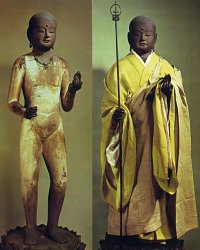

Hadaka Jizō 裸地蔵

Nude Jizō. Carved nude but dressed in clothing. Another deity sometimes carved naked is Benzaiten. The practice of carving nude statues may have originated in China, although there is scant evidence to support this claim. Such statues became popular in the Kamakura Period, but the practice was never firmly established -- only 100 or so extant statues of nude deities are known in Japan. Examples include the Hadaka Jizō of Denkōji Temple 伝香寺 in Nara, dated to 1228, a stone statue at Kokuan Enkōji Temple 国安円光 in Hyōgo Prefecture, and the nude version of the Substitute Jizō (Migawari Jizō) at Enmeiji Temple 延命寺 in Kamakura

The Hadaka Jizō wood statue at Denkōji Temple 伝香寺 in Nara is generally not open to public viewing, but each year on July 23/24 (Jizō's memorial day), the statue is dressed anew and the prior-year clothing is torn into small pieces and presented as talismans to believers. According to temple legend, the statue was commissioned by a nun and is adorned with a beautiful necklace. During the Jizō Bon Ceremony, local kindergarten children come here to pray.

Writes Zen teacher and practicing pediatrician Jan Chozen Bays:

- "Two nude statues of Jizō are in the city of Nara, one now found at Shinyakushi-ji Temple and another at Denkōji Temple. Both of these have genitalia that are neither clearly feminine nor masculine. The Shinyakushi Jizō has a simple lump groin and the Denkōji Jizō has only a line carved in a corkscrew shape. There is speculation that these are representations of the 'sheathed' or 'retractable' penis, one of the distinguishing marks of a Buddha. The ambiguous genitalia of these Jizō statues also may relect the dual male and female origin and attributes of Jizō."

The Hadaka Jizō wood statue at Enmeiji Temple 延命寺 in Kamakura is open to public viewing, but it is nearly always dressed in robes and shown standing atop a game board. According to temple records, the wife of regent Hōjō Tokiyori 北条時頼 (1227-1263) built this temple in honor of Jizō and commissioned the carving of a naked statue of Jizō depicted with female pudenda. This statue is connected to a very curious old story in which Tokiyori and his wife were playing a board game called Sugoroku 双六. They had agreed that the loser would disrobe entirely. The consort lost. Filled with shame at her predicament, she prayed to Jizō to save her. To her amazement, a naked statue of Jizō appeared on the game board in her stead. Thus this statue is popularly known as the Migawari Jizō (Substitute Jizō). The statue on display at Enmeiji is attributed to famed sculptor Unkei 運慶, but Unkei died in 1223 so this attribution must be considered false. Enmeiji is one of 24 sites on the Jizō Pilgrimage in Kamakura.

Hanakake Jizō 鼻欠け地蔵 or 鼻欠地蔵

Noseless Jizō. This curious deity is mentioned in the Honchō Zokugen Shi 本朝俗諺志 (Records on Popular Japanese Proverbs), written in 1746 by Kikuoka Senryō 菊岡沾凉. It refers to a statue of the Noseless Jizō (Hanakake Jizō 鼻かけ) carved on a stone stupa erected in 1717 at Honseiji Temple 本誓寺 in Edo's Fukagawa district, which was prayed to for recovery from all manner of diseases. Says De Visser: "After their prayers they would fill a little bamboo tube with Tamukeno Mizu 手向けの水 (the water placed before a grave as an offering to the spirit of the interred) and take this home. When their prayers were fulfilled, they filled a kawarake (unglazed earthen vessel) with salt and offered it to this Jizō as a sign of gratitude."

The curious name stems from various legends. Says site contributor Gabi Greve: At Sasaurawan Bay 楽々浦湾 is a small sanctuary for the Noseless Jizō. The statue was reportedly discovered by fishermen in the sea. As a thank you for saving him, this Jizō produced rice grains out of his nose. One greedy man in the neighborhood cut off the nose to have all the rice for himself. But afterwards the nose stopped pouring out rice grains and the statue appeared without a nose. During the annual July festival at Sasaurawan Bay, the local people pound mochi (rice cakes). Elsewhere in Japan, the residents of Yoshigawa 良川 tell a story about a man who walked in the forest alone at night in the area of Tango (Tottori) and saw a fox pulling a Jizō statue behind him. When he checked the area later, the statue of Jizō had lost its nose.

Harahoge Jizō はらほげ地蔵

Says site contributor Gabi Greve: "This is a group of six Jizo statues standing on the beach of Iki island 壱岐市 (Nagasaki Prefecture). When the tide is up, they stand in water up to their waist, and on the chest, they have a small hole (hara ga hogete iru). The holes are difficult to see because the little red aprons cover them completely. Maybe the holes were made on purpose to keep the offerings from being washed into the sea. Or to facilitate to make offerings from the boats during high tide. Or as a talisman to protect the people from smallpox. Or the Jizō were put up to pray for the safety of whalers in olden times and for the safety of the women divers (ama), who catch the local uni 海栗 sea urchins.

Hawaii Jizō - Guardian of Fishermen and Swimmers

In Hawaii's coastal areas, fishermen and swimmers look to Jizo for protection. Soon after their arrival in the late 1800s, issei (first-generation Japanese) shoreline fishermen began casting for ulua on Hawaii's treacherous sea cliffs, where they risked being swept off the rocky ledges. In response to numerous drownings, Jizo statues were erected near dangerous fishing and swimming sites, including popular Bamboo Ridge, near the Blowhole in Hawaii Kai; Kawaihâpai Bay in Mokulç'ia; and Kawailoa Beach in Hale'iwa. Guardian of the Sea tells the story of a compassionate group of men who raised these statues as a service to their communities.

Higiri Jizō 日限地蔵

Time-Limiting Jizō. A form of Jizō who listens to prayers within a set timeframe (only on specified days of the week or month). Those who visit and pray within that timeframe reportedly have their prayers answered. According to one folk story from Gunma Prefecture, a long time ago there was a weaver who was greatly troubled because a monster appeared in his house every night. One night, though, he shot a rifle at him, but the monster was not to be found, not even his shadow. When it grew light enough to see, the weaver discovered some drops of blood, but they disappeared in the garden of Kannon-In Temple (located at Kiryu, Gunma). A few nights later, the weaver saw Jizō in a dream. Jizō said to him: "I stand outside your house every night to protect you. But because I stand outdoors, the people don't believe in me. I want you to build a temple for me so that I can protect many people. Then, if you set aside a special day each month, I promise to fulfill the prayers of anyone who prays to me on that day.

Hitaki (Kuro) Jizō 火焚地蔵

Fire-Kindling Jizō. Also known as Kuro Jizō 黒地蔵 (Black Jizō) or Hifuse Jizō 火伏地蔵. This is just one of many forms of Jizō known as the Migawari Jizō or Substitute Jizō (one who vicariously receives our injuries and wounds). According to Japanese legends, Jizō descends into the infernal regions to witness the punishments and tortures of condemned souls (e.g., sinners being boiled in large pots of water). Jizō is so pained by their agony that, for a time, Jizō assumes the role of their custodian (a soldier of hell or Gokusotsu 獄卒) and greatly reduces the intense heat of the purgatorial fires to lessen their torment. The work of controlling the fires made Jizō black with soot and smoke. This Jizō is also considered the modern patron of firemen. A famous wood statue of this Jizō, dated to the Kamkura period and standing 170.5 cm in height, is housed at Kakuonji Temple 覚園寺 in Kamakura. See photo below. Kakuonji is one of 24 sites of the Jizō Pilgrimage in Kamakura. There are other similar forms of Jizō, such as the Hōyake Jizō 頬焼地蔵 (Jizō With Burnt Cheeks).

Writes KCN-NET:

- "Based on temple legends, each time the Black Jizō statue at Kakuonji was repainted to restore its original beauty, it turned black again very soon. Locals also believe the Black Jizō grants prayers for, among other things, safe birth, healthy children, recovery from illness, protection from misfortune, and happiness. A large number of small Jizō statues are positioned on both sides of the Black Jizō and are called Sentai Jizō 千体地蔵 (lit. One Thousand Jizō). When local people borrow one of these "One Thousand Jizō" to venerate at home and their prayers are answered, they paint the statue anew or have a new one made, and then return it here. It is said that if you have deep faith in Kuro Jizō, you will be able to find among the thousand statues one that resembles a person you miss and desire to see again."

Hōroku Jizō ほうろく地蔵

Earthenware Jizō. Devotees offer earthenware plates to images of this Jizō when they suffer from headaches or other head ailments. They write their prayers on the earthenware, and present the plates to Jizō, or place it atop the statue's head. One well-known Hōroku Jizō is located at Daienji Temple 大円寺 (Tokyo).

The term Hōroku 法烙 refers to flat plates used in temples. Says Gabi Greve:

- "During the ancestor festival O-Bon in August temples provide hōroku that you can place on the graves and make a little fire in them to welcome the ancestors."

Hōyake Jizō 頬焼地蔵

Jizō With Burnt Cheeks. One of many different forms of the Migawari Jizō or Substitute Jizō (one who vicariously receives our injuries and wounds). Found in various localities throughout Japan. Hōyake Jizō appears in the 1698 document Setsuyō Gundan. Using this as a reference, scholar De Visser (1876-1930) writes: "Located at the Seshuu-in 専修院 in Tanimachi Town 谷町 in Osaka, this Jizō was said to have suffered in hell as a substitute for a woman, who in this way escaped the terrible punishment of being beaten by yakekane 焼鉄 or burning irons. This image was a Reibutsu 靈佛, an idol which by much ling (Chn. = 靈 or 霊, manifestation of vital power) showed its divinity by hearing the prayers of its worshippers and performing miracles." This version of Jizō may also be compared with that of the Hitaki Jizō (Black Jizō) statue at Kakuonji Temple in Kamakura.

Another similar story appeared in the Uji Shūi Monogatari 宇治拾遺物語 (a document from the early 13th century). Writes scholar De Visser: "This work tells a story about the Buddhist priest Ganō 賀能, who one day took shelter from the rain in a Jizō chapel in in Yokogawa no Hannya-dani on Hieizan 比叡山 (near Kyoto). As the roof of the chapel was dilapidated and the rain dripped upon the Jizō image, he pitied it and covered it with his own hat. After death he fell into hell, because he had committed many evil deeds, and was thrown into an iron caldron, in which his body was burned. While he was thus suffering immensely, a priest, the Jizō of Yokogawa, appeared and pulled him out of the kettle, scalding his own forehead, foot and shoulder. Then Ganō revived and when he visited the chapel he saw that the corresponding parts of the Jizō image were burned."

Jizō Bon 地蔵盆 and Jizō Festival 地蔵祭

The 24th day of each month is considered Jizō's ENNICHI 縁日. Ennichi literally means "related day." This is translated as sacred day or holy day; it is a monthly memorial day with special significance to a particular Buddha or Bodhisattva. Saying prayers to the deity on this day is believed to bring greater merits and better results than on regular days. The Heian-era document Konjaku Monogatari 今昔物語 gives Jizō's Ennichi as the 24th day of each month.

Even today, at numerous locations throughout Japan, the annual Jizō Bon 地蔵盆 ceremony is held nationwide on August 24. Traditionally known as the Confession of Jizō Ceremony (Jizō Bon) in which people confess the faults they committed during the year in the hopes of erasing bad karma, and to pray that Jizō will grant them longevity and protect their children. Today it is often combined with a children's festival (Jizō-sai 地蔵祭) in which children gather into groups and rotate a lengthy rosary (juzu-kuri 数珠繰り) made of large beads. In some localities, children believe that tapping their forehead against the beads will bring them luck. In many areas, children are allowed to paint the faces of the local Jizō statues (Keshō Jizō 化粧地蔵, lit. Jizō with Makeup) or to wash the statues and dress them in new red bibs, hats, and robes. Red lanterns are hung at Jizō sites with the inscription "Hail to Jizō Bosatsu," and children eat red-colored festival food. Adds site contributor Gabi Greve: "Today it is customary to have the Jizō-bon on both August 23 and 24 to coincide with the Jizō-sai (Jizō fairs), but a growing number of communities have recently changed the dates to the nearest Saturday and Sunday."

Says Yuki Yamaguchi:

- "During Jizō Bon, Jizō statues are washed and decorated with red bibs and red hats. We serve meals to thank them for protecting children. Jizō-bon is traditionally held for two days (August 23- 24). Everyone gathers in a community hall to prepare for it. I would get to wear my yukata (summer kimono). Kids receive a lantern with their name on and also halloween-style snack packs. There are games and entertainment and "bon-odori" dancing. Bon-odori is a group dance. Everyone does the same dance, moving in a circle around a float where taiko (japanese drum) is played. We don't take any formal lessons but everybody knows the dance. You learn by watching the person in front of you. I like this type of group dancing. Everybody moves the same way and goes around and around and around."

Kinomoto Jizō 木之本地蔵

Kinomoto literally means "Root of the Tree, or "Origin of the Tree," or "Base of the Tree." The Jizō statue at Kinomoto Jizō-in Temple, Nagahama Town 長浜市 (Shiga Prefecture) is known for healing eye diseases. Locals call the deity Me no Hotokesama 目の仏様 (the Eye Buddha). According to Gabi Greve: "Once upon a time, there lived a frog in the temple compound, who saw countless patients with eye diseases come visiting and praying for a cure. 'Is there anything I can do to help them?' he asked. Then the frog made a vow: 'I will close one of my eyes to experience their pain and will ask the divine grace and help of Jizō Bosatsu to cure their diseases.' When all people suffering from eye afflictions are cured, this frog will once again open its eye. This temple maintains a "hidden" image of Jizō, one not shown to the public. But there is a similar large six-meter statue of Jizō in the temple compound. At its feet are countless figurines of little frogs, which are offered by devotees who hope to gain a cure for their eye ailments."

Koyasu Jizō 子安地蔵

Lit. = Easy Childbirth Jizō. This form of Jizō grants easy and safe delivery to woman, and in modern times is often depicted holding a child, or with children in his lap or at his feet. Koyasu Jizō is venerated at numerous temples throughout Japan, including Tatsueji Temple 立江寺 in Shikoku, which was built in 747 by order of Emperor Shōmu 聖武 (reigned 724 to 749). The emperor also ordered the construction of a Jizō statue, which was called the Koyasu-no-Jizō, and prayed to it to grant easy childbirth to the pregnant crown princess. The famed monk Kōbō Daishi 弘法大師 (774-835) reportedly later visited the temple and made a larger statue, which thereafter became the temple's central idol.

Another notable example is Koyasuzan Obitoke-dera 子安山帯解寺 (Temple for Loosening the Girdle, i.e. granting easy birth) in Nara. It houses a Kamakura-era statue of Koyasu Jizō, considered the oldest extant Koyasu Jizō image in Japan. This temple was built in 851 by Fujiwara no Akiko 藤原彰子, the consort of Emperor Montoku 文徳天皇, to honor Jizō for helping her survive a long and difficult pregnancy. The child later became Japan's first boy emperor.

It is quite logical that Jizō was associated early on with women, pregnancy, fertility, and children -- for Jizō can be translated literally as "Womb of the Earth" (JI 地 = earth, ZŌ 蔵 = womb). Along with Kannon Bosatsu (Goddess of Mercy), Jizō is considered a savior par-excellance for women and children, and numerous forms of Jizō are thus venerated by women praying for children, easy delivery, help with child rearing, and other female concerns. For more details on these associations, jump to Jizō, Women, & Pregnancy -- which includes a description of the Hara-Obi Jizō 腹帯地蔵 (Belly Girdle Jizō).

Additionally, Jizō incorporates many of the functions of Koyasu-sama (aka Koyasu-gami), the Shintō goddess of pregnancy, safe childbirth, and the healthy growth and development of children. Shintō shrines dedicated to Koyasu-sama still exist in modern times. These shrines are known as Asama Shrines 浅間神社 (also pronounced Sengen). More than 1,000 Asama (Sengen) shrines exist across Japan, with the head shrines standing at the foot and the summit of Mount Fuji itself. These sanctuaries are dedicated to Koyasu's namesake, the mythical princess Konohana Sakuya Hime (木花之佐久夜毘売), the Shintō deity of Mount Fuji, of cherry trees in bloom, and the patron of safe delivery. In Shintō mythology, Konohana (lit = tree flower) is the daughter of Ōyamatsumi (the earthly kami of mountains). She was married to Ninigi 邇邇芸尊 (heavenly grandchild of sun goddess Amaterasu), became pregnant in a single night, and gave birth to three children while her home was engulfed in fire -- thus her role as the Shintō kami who grants safe childbirth. In some accounts she died in the fire, and thus she is likened to the short-lived beauty of the cherry blossom.

Despite the survival of Shintō's Koyasu-sama into modern times, she has been largely supplanted by her Buddhist equivalents, known as Koyasu Jizō, Koyasu Kannon, and Koyasu Kishibojin.

Kubifuri Jizō 首振地蔵

Turn-My-Head Jizō. A statue of this Jizō is located just outside the entrance gate to Kiyomizu-dera 清水寺 in Kyoto. Devotees turn the head of this Jizō image when asking Jizō for a favor. The practice began sometime in the Edo period, and is probably a variation of the Shintō Haykudo Mairi tradition and the Jizō Wheel tradition (itself a variant of the Haykudo Mairi practice).

Kubikire Jizō 首切れ地蔵

Jizō with Head Cut Off. This Jizō is one of many different forms of the Migawari Jizō or Substitute Jizō (one who vicariously receives our injuries and wounds). The Kubikire Jizō appears in the 1698 document Setsuyō Gundan, which tells us that monk Junrei was saved by this Jizō when he was attacked at night by robbers. Jizō served as his substitute, offering his head instead of Junrei's. When the monk awoke in the morning, he discovered a bloodstained image of Jizō (at Anryu-machi, Settsu province) with its head laying on the ground. The old province of Settsu is today part of eastern Hyōgo Prefecture and northern Osaka Prefecture.

Michibiki Jizō 導き地蔵,Guiding Jizō

In Kamakura city, there is a structure close to both Gokurakuji Temple and Sakurabashi Bridge that houses a Jizō statue named Michibiki Jizō, translated as "Guiding Jizō." This form of Jizō protects children from impediments to their growth and prevents mishaps within his field of vision.

Migawari Jizō 身代り地蔵

Substitute Jizō, one who substitutes for our suffering, one who vicariously receives our injuries and wounds. There are numerous versions and stories of the Substitute Jizō. In one of many legends, this emanation of Jizō once saved a Japanese princess, who was attacked by a villain, by putting himself in front of the attacker's sword. For a time, it is said, the statue had a scar across its face where the villain's sword had fallen. This type of Jizō is known as the Substitute Jizō (Migawari Jizō 身代り地蔵), one who substitutes himself for our suffering.

Another well-known substitute is Tachiyama Jizō 立山地蔵, who takes the place of a poor peasant woman so she can rest once a month (see Farmers & Peasants Jizō for more examples involving agricultural concerns). Another interesting example comes from the Garan Kaiki Ki 伽藍開基記 (Records of the Founding of Buddhist Temples), written in 1689. It states that Emperor Shōtoku 称徳天皇 (718 - 770) ordered the construction of a temple dedicated to Jizō on sacred Mt. Ōyama 大山 (present day Tottori Prefecture) after hearing a miracle story about a Jizō image in the possession of a Jizō devotee named Toshikata, who lived at the foot of Ōyama mountain. Writes scholar De Visser: "One day, when Toshikata came home after having shot a stag in the mountains, and was about to worship Jizō, he was much frightened by seeing his arrow sticking in the image and blood flowing out of the wound. He understood that Jizō in his great compassion for all living beings had given his own body as a substitute for the stag and had been wounded in its place. This caused him to shave his head and to become a monk; he had his house pulled down and a Jizō Hall built on the spot. When the Emperor heard this story, the Emperor ordered the construction of a temple in the same spot in order to dedicate this to the miraculous image."

The temple is known at Daisenji 大山寺, but records about its origin are conflicting. The Genkō Shakusho (written before 1346) says the famous monk Ennin 円仁 (794-864; posthumous title Jikaku Daishi 慈覚大師) founded the temple. Other well-known examples of the Substitute Jizō include Hitaki Jizō 火焚地蔵 (Fire-Kindling Jizō or Black Jizō), Hōyake Jizō (Jizō With Burnt Cheeks), and Shōgun Jizō (Battlefield Jizō)

Miso Jizō みそ地蔵 (Bean Paste Jizō)

At Saizōji Temple (in Higashiyama, Hiroshima), people bring a flat pack of miso (bean paste), put it on the head of a seated Jizō statue, say a prayer, and then put the miso pack on their own head in the hopes their prayers will be answered (e.g., prayers to cure illness, to pass the school exams, to gain intellegence). In this area of Hiroshima, the Miso Jizō is even more popular than Michizane Sugawara, a courtier in the Heian period who was deified after death -- he is considered a Shintō deity and venerated as the patron of scholarship, learning, and calligraphy at Tenjin shrines throughout Japan. Miso means bean paste. It is also short for "nōmiso," the latter term meaning "brain." Thus, Miso Jizō is a play on sounds.

Misoname Jizō みそなめ地蔵 (Miso Licking Jizō)

In other locations, people worship the so-called Misoname Jizō or "Miso-Licking Jizō." According to folklore, people who are granted their wishes are supposed to visit "Miso Licking" temples and smear miso around the mouth of the Jizō statue. In other areas, people spread miso on Jizō statues to cure sickness, tooth aches, and eye diseases. The basic belief is to put miso on the statue in the same location as your ailment -- on Jizō's teeth if you have a tooth ache, on Jizō's eye if you have an eye disease, etc. This symbolism is similar to another manifestation of Jizō called the Migawari Jizō (Substitution Jizō). This latter Jizō "substitutes" himself for the suffering of the people, curing them by taking on their pain. For much more on Miso Jizō, the Miso Licking Jizō, and other unique Japanese manifestations of this beloved deity, please see Gabi Greve's Miso Jizō page. There is another version of Jizō called the Shioname Jizō 塩なめ地蔵 (Salt-licking Jizō) enshrined at Kōsokuji Temple 光触寺 (Juniso) in Kamakura, which is one of the temples on the 24-temple Kamakura Jizō Pilgrimage.

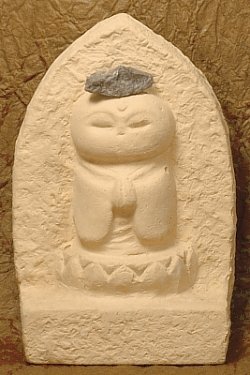

Mizuko Jizō 水子地蔵 & Mizuko Ceremony in Japan

Lit = Water-Child Jizō, guardian of aborted children and kids who die prematurely, whose souls go to a hell-realm known as Sai-no-Kawara. In modern Japan, Jizō is popularly venerated as the guardian of unborn, aborted, miscarried, and stillborn babies. These roles were not assigned to Jizō in earlier Buddhist traditions from mainland Asia; they are instead modern adaptations unique to Japan.

Excerpt from "Jizō Bodhisattva" by Chozen Roshi. The most common form of Jizō made in Japan today is the Mizuko Jizō, who is often portrayed as a monk with an infant in his arms and another child or two at his feet, clutching the skirt of his robe. [Editor's Note: Koyasu Jizō shares same iconography] The Mizuko Jizō is the central figure in a popular but somewhat controversial ceremony called the Mizuko Kuyō 水子供養.

The words Ku-yō are composed of two Chinese characters with the literal meaning "to offer" and "to nourish". The underlying meaning is to offer what is needed to nourish life energy after it is no longer perceptible in the form of a human or occupying a body we can touch. In actual use Kuyō refers to a memorial service and Mizuko Kuyō to a memorial service for infants who have died either before birth or within the first few years of life. An image of the Mizuko Jizō usually is the central figure on the altar at such a ceremony. Grieving parents may buy a small statue of Mizuko Jizō to place on the family altar or in a cemetery as a memorial for their child.

The two Chinese characters in the word mizu-ko are literally translated "water" and "baby". It is a description of the unborn beings who float in a watery world awaiting birth. The Japanese perceived that all life is originated from the sea long before evolutionary theory proposed this. Their island home and all its inhabitants float in the ocean, which is the source of much of their nutrition. In actual use, the term "mizuko" includes not only fetuses and the newly born, but also infants up to one or two years of age whose hold on life in the human realm is still tenuous.

In Japan young children are regarded as "other worldly" and not fully anchored in human life. Fetuses are still referred to as kami-no-ko or "child of the gods" and also as "Buddha". Before the twentieth century, the probability that a child would survive to age five or seven was often less than 50 percent. Only after that age were they "counted" in a census and could they be "counted upon" to participate in the adult world. Children were thought of as mysterious beings in a liminal world between the realm of humans and gods. Because of this the gods could speak through them. For centuries prepubescent children in Japan have been chosen as chigo 稚児, or "divine children", who do divination and function as oracles. Even today children below school age still are allowed a somewhat heavenly existence, indulged and protected without many expectations or pressures. They often sleep in bed with their parents and younger siblings until age seven. School entry and displacement from the parental bed can come as a rude shock.

Mizuko Jizō Book

Writes Chozen Roshi: "People in America and Europe have only recently become acquainted with Jizō Bodhisattva, but mistaken beliefs among Westerners about Jizō already exist. The Mizuko Jizō, although currently popular, revered, and omnipresent in Japan, is not an ancient Jizō. Nor is it the only form of Jizō. The term "mizuko" does not appear in Buddhist or Shintō scriptures. The mizuko kuyō is not an ancient rite nor was it originally a Buddhist ceremony. Both the Mizuko Jizō and the mizuko ceremony arose in Japan in the 1960s in response to a human need, to relieve the suffering emerging from the experience of a large number of women who had undergone abortions after World War II."

Mizuko Jizō Anticedents (Jizō Legend in Japan)

The cult of Mizuko Jizō in Japan emerged only recently (1960s), but it no doubt draws its inspiration from much earlier tales of Jizō's salvific powers. Based on legends attributed to the Jodō Sect (Pure Land Sects devoted to Amida Buddha) around the 14th or 15th century, children who die prematurely are sent to the underworld to undergo judgment. Even though they died before hearing the teachings of the Buddha, or before they could accumulate good or bad karma, they must still undergo judgment as do all people. Even the innocent souls of unborn fetuses are sent to the underworld, for folk wisdom says they are guilty of causing great sorrow to their parents. They are sent to Sai no Kawara, the river of souls in purgatory, where they pray for Buddha's compassion by building small stone towers, piling stone upon stone. But underworld demons, answering to the command of the old hag Shozuka no Baba, soon arrive and scatter their stones and beat them with iron clubs. But, no need to worry, for Jizō comes to the rescue. In one version of the story, Jizō hides the children in the sleeves of his robe. This traditional Japanese story has been adapted to modern needs, and today, children who die prematurely in Japan are called "mizuko," or water children, and the saddened parents pray to Mizuko Jizō. This form of Jizō is unique to Japan, and did not appear until after the end of World War II. See Mizuko Jizō above for details.

Mizuko, Stones, and Jizō

Even today, you will invariably find little heaps of stones and pebbles on or around Jizō statues, as many bereaved parents believe that a stone offered in faith will shorten the time their dead child suffers in the underworld and help their child in performing his/her penance in the netherworld. (See the preceding paragraph for one origin of this tradition.) You will also notice that Jizō statues are often wearing tiny garments. Since Jizō is the guardian of dead children, sorrowing parents bring the little garments of their lost ones and dress the Jizō statue in hopes Jizō will especially protect their child during their time in the netherworld. A little hat or bib (often red in color) or toy is often seen as well, the gift of a rejoicing parent whose child has been cured of dangerous sickness thanks to Jizō's intervention, or a gift to help the deceased child in the afterlife.

Omokaru Jizō おもかる地蔵尊

Omokaru-ishi literally means "heavy or light stones." There are numerous variations for these types of stones and statues. Essentially, you make a wish and try to lift the stone (or statue). If you can carry it (karui = light), your wish will be granted. If you cannot carry it (omoi = heavy), then you have to come back another day and try again. Sometimes a statue of Jizō Bosatsu is used instead of a stone.

Onegai Jizō お願い地蔵

Literally the "wish-giving" or "ask-a-favor" Jizō. At many temples, visitors can buy tiny images of Jizō, which they deposit around the main Jizō statue when praying for Jizō's help. This is probably an extension of Sentai Jizō (1,000 Jizō) traditions.