Luoyang

Luoyang

洛阳市 Loyang | |

|---|---|

Top: Longmen Grottoes, Bottom left: White Horse Temple, Bottom right: Paeonia suffruticosa in Luoyang and Longmen Bridge | |

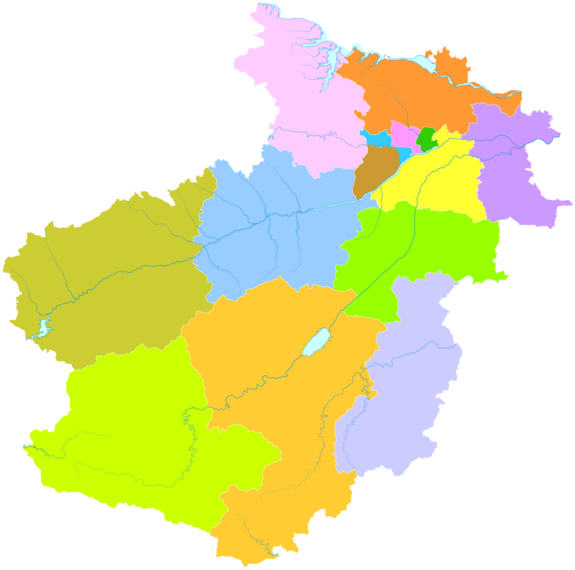

Location of Luoyang City jurisdiction in Henan | |

Location on the North China Plain | |

| Coordinates (Luoyang municipal government): 34°37′11″N 112°27′14″E / 34.6197°N 112.4539°E | |

| Country | People's Republic of China |

| Province | Henan |

| Municipal seat | Luolong District |

| Government | |

| • Party Secretary | Li Ya |

| • Mayor | Liu Wankang |

| Area | |

| • Prefecture-level city | 15,229.15 km2 (5,880.01 sq mi) |

| • Urban | 810.4 km2 (312.9 sq mi) |

| • Metro | 1,402.3 km2 (541.4 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 144 m (472 ft) |

| Population (2020 census, 2018 for otherwise)[1] | |

| • Prefecture-level city | 7,056,699 |

| • Density | 460/km2 (1,200/sq mi) |

| • Urban | 2,249,300 |

| • Urban density | 2,800/km2 (7,200/sq mi) |

| • Metro | 2,751,400 |

| • Metro density | 2,000/km2 (5,100/sq mi) |

| GDP[2][3] | |

| • Prefecture-level city | CN¥ 382.0 billion US$ 57.5 billion |

| • Per capita | CN¥ 56,410 US$ 8,493 |

| Time zone | UTC+8 (China Standard) |

| Area code | 379 |

| ISO 3166 code | CN-HA-03 |

| Ethnicities | Han, Hui, Manchu, Mongolian |

| County-level divisions | 15 |

| License plate prefixes | 豫C |

| Website | www |

Luoyang (simplified Chinese: 洛阳; traditional Chinese: 洛陽; pinyin: Luòyáng) is a city located in the confluence area of the Luo River and the Yellow River in the west of Henan province. Governed as a prefecture-level city, it borders the provincial capital of Zhengzhou to the east, Pingdingshan to the southeast, Nanyang to the south, Sanmenxia to the west, Jiyuan to the north, and Jiaozuo to the northeast. As of December 31, 2018, Luoyang had a population of 6,888,500 inhabitants with 2,751,400 people living in the built-up (or metro) area made of the city's five out of six urban districts (except the Jili District not continuously urbanized) and Yanshi District, now being conurbated.[1] By the end of 2022, Luoyang Municipality had jurisdiction over 7 municipal districts, 7 counties and 1 development zone. The permanent population is 7.079 million.[4]

Situated on the central plain of China, Luoyang is among the oldest cities in China and one of the cradles of Chinese civilization. It is the earliest of the Four Great Ancient Capitals of China.

Names[edit]

The name "Luoyang" originates from the city's location on the north or sunny ("yang") side of the Luo River. Since the river flows from west to east and the sun is to the south of the river, the sun always shines on the north side of the river. Luoyang has had several names over the centuries, including Luoyi (洛邑) and Luozhou (洛州), but Luoyang has been its primary name. It has also been called Dongdu (東都; 'eastern capital') during the Tang dynasty, Xijing (西京; 'western capital') during the Song dynasty, or Jingluo (Chinese: 京洛; lit. 'capital Luo'). During the rule of Wu Zetian, the only female emperor in Chinese history, the city was known as Shendu (神都; 'divine capital'). Luoyang was renamed Henanfu (河南府) during the Qing dynasty but regained its former name in 1912.

History[edit]

Classical era[edit]

The greater Luoyang area has been sacred ground since the late Neolithic period.[5] This area at the intersection of the Luo River and Yi River was considered to be the geographical center of China.[citation needed] Because of this sacred aspect, several cities – all of which are generally referred to as "Luoyang" – have been built in this area. In 2070 BC, the Xia dynasty king Tai Kang moved the Xia capital to the intersection of the Luo and Yi and named the city Zhenxun (斟鄩). In 1600 BC, Tang of Shang defeated Jie, the final Xia dynasty king, and built Western Bo, (西亳), a new capital on the Luo River. The ruins of Western Bo are located in Luoyang Prefecture.

In 1036 BC a settlement named Chengzhou (成周) was constructed by the Duke of Zhou for the remnants of the captured Shang nobility. The Duke also moved the Nine Tripod Cauldrons to Chengzhou from the Zhou dynasty capital at Haojing. A second Western Zhou capital, Wangcheng (also: Luoyi) was built 15 km (9.3 mi) west of Chengzhou. Wangcheng became the capital of the Eastern Zhou dynasty in 771 BC. The Eastern Zhou dynasty capital was moved to Chengzhou in 510 BC. Later, the Eastern Han dynasty capital of Luoyang would be built over Chengzhou. Modern Luoyang is built over the ruins of Wangcheng, which are still visible today at Wangcheng Park.[6]

Qin Shi Huang's chief minister, Lu Buwei, was given Luoyang. Lu began programs to develop and beautify Luoyang. It is said that Liu Bang visited Luoyang and considered making it his capital but was persuaded to reconsider by his ministers to turn to Chang'an instead for his capital.[7]

Han dynasty[edit]

In 25 AD, Luoyang was declared the capital of the Eastern Han dynasty on November 27 by Emperor Guangwu of Han.[8] The city walls formed a rectangle 4 km south to north and 2.5 km west to east, with the Gu River, a tributary of the Luo River just outside the northern eastern walls. The rectangular Southern Palace and the Northern Palace were 3 km apart and connected by The Covered Way. In 26, the Altar of the Gods of the Soils and Grains, the Altar of Heaven, and the Temple of the eminent Founder, Emperor Gao of Former Han were inaugurated. The Imperial University was restored in 29. In 48, the Yang Canal linked the capital to the Luo. In 56, main imperial observatory, the Spiritual Terrace, was constructed.[9]

For several centuries, Luoyang was the focal point of China. In AD 68, the White Horse Temple, the first Buddhist temple in China, was founded in Luoyang. The temple still exists, though the architecture is of later origin, mainly from the 16th century. An Shigao was one of the first monks to popularize Buddhism in Luoyang.

The ambassador Banchao restored the Silk Road during the Eastern Han dynasty, thus making Luoyang the eastern terminus of the Silk Road during the Han dynasty.

In 166 AD, the first Roman mission, sent by "the king of Da Qin [the Roman Empire], Andun" (Marcus Aurelius Antoninus, r. 161–180 AD), reached Luoyang after arriving by sea in Rinan Commandery in what is now central Vietnam.[10]

The late 2nd century saw China decline into anarchy:

The decline was accelerated by the rebellion of the Yellow Turbans, who, although defeated by the Imperial troops in 184 AD, weakened the state to the point where there was a continuing series of rebellions degenerating into civil war, culminating in the burning of the Han capital of Luoyang on 24 September 189 AD. This was followed by a state of continual unrest and wars in China until a modicum of stability returned in the 220s, but with the establishment of three separate kingdoms, rather than a unified empire.[11]

Wei and Jin dynasties[edit]

On April 4, 190 AD,[12] Chancellor Dong Zhuo ordered his soldiers to ransack, pillage, and raze the city as he retreated from the coalition set up against him by regional lords all over China. The court was subsequently moved to the more defensible western city of Chang'an (modern Xi'an). Following a period of disorder, during which warlord Cao Cao held the last Han emperor Xian in Xuchang (196–220), Luoyang was restored to prominence when his son Cao Pi, Emperor Wen of the Wei dynasty, declared it his capital in 220 AD. The Jin dynasty, successor to Wei, was also established in Luoyang. At the height of Jin rule, Luoyang had a population of 600,000 and was probably the second largest city in the world after Rome.[13]

During the Upheaval of the Five Barbarians in 311 AD, Western Jin was forced to move its capital to Jiankang (modern day Nanjing) and become Eastern Jin. The Xiongnu armies of Liu Cong destroyed Luoyang in the Disaster of Yongjia. Following the sack, it would take until 495 AD before the city was a major population hub again.[13] The same fate befell Chang'an in 316 AD.[14] Every single diaspora Sogdian and Indian living Luoyang at the time died due to the Xiongnu sack.[15][16][17][18][19][20][21][22][23][24][25] A large battle between the forces of Liu Yao of Former Zhao and Shi Le of Later Zhao took place outside the remnants of the city in 328, with Shi obtaining a decisive victory, capturing Liu Yao and leading to the collapse of Former Zhao.[26]

Northern Wei[edit]

| Luoyang | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

"Luoyang" in Simplified (top) and Traditional (bottom) Chinese characters | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 洛阳 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 洛陽 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Literal meaning | "Northern bank of the Luo [River]" | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||

In winter 416, Luoyang fell to Liu Yu's general Tan Daoji. In 422, Luoyang was captured by Northern Wei. Liu Song general Dao Yanzhi took the city back, but by 439 the Wei conquered the city definitively. In 493 AD, Emperor Xiaowen of the Northern Wei dynasty moved the capital from Datong to Luoyang, moving over 150,000 people to the site by 495,[27] and started the construction of the rock-cut Longmen Grottoes. More than 30,000 Buddhist statues from the time of this dynasty have been found in the caves. Many of these sculptures were two-faced. At the same time, the Shaolin Temple was also built by the Emperor to accommodate an Indian monk on the Mont Song right next to Luoyang City. The Yongning Temple (永宁寺), the tallest pagoda in China, was also built in Luoyang. The city reached a population of 600,000 at its height during the Northern Wei.[27] The city was destroyed by the warlord Gao Huan, who captured the city and forced its population to move to his capital at Ye in 534.[28] The old city was the site of numerous battles between Western Wei (and its successor Northern Zhou) and Eastern Wei (and its successor Northern Qi) between 538 and 575

Sui and Tang dynasties[edit]

When Emperor Yang of Sui took control in 604 AD he founded the new Luoyang on the site of the existing city using a layout inspired by his father Emperor Wen of Sui's work in newly rebuilt Chang'an.[29][30]

During the Tang dynasty, Luoyang was Dongdu (東都), the "Eastern Capital", and at its height had a population of around one million, second only to Chang'an, which, at the time, was the largest city in the world.[32]

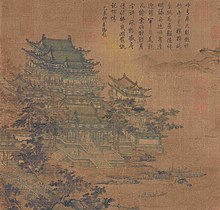

During an interval in the Tang dynasty, the first and the only empress in Chinese history – Empress Wu, moved the capital of her Zhou dynasty to Luoyang and named it as Shen Du (Capital of the God). She constructed the tallest palace in Chinese history, which is now in the site of Sui Tang Luoyang city. Luoyang was heavily damaged during the An Lushan Rebellion.[7]

Epitaphs were found dating from the Tang dynasty of a Christian couple in Luoyang of a Nestorian Christian Sogdian woman, Lady An (安氏), who died in 821, and her Nestorian Christian Han Chinese husband, Hua Xian (花献), who died in 827. These Han Chinese Christian men may have married Sogdian Christian women because of a lack of Han Chinese women belonging to the Christian religion, limiting their choice of spouses among the same ethnicity.[33] Another epitaph in Luoyang of a Nestorian Christian Sogdian woman also surnamed An was discovered and she was put in her tomb by her military officer son on 22 January, 815. This Sogdian woman's husband was surnamed He (和) and he was a Han Chinese man and the family was indicated to be multiethnic on the epitaph pillar.[34] In Luoyang, the mixed raced sons of Nestorian Christian Sogdian women and Han Chinese men has many career paths available for them. Neither their mixed ethnicity nor their faith were barriers and they were able to become civil officials, a military officers and openly celebrated their Christian religion and support Christian monasteries.[35] Central Asians like Sogdians were called "Hu" (胡) by the Chinese during the Tang dynasty. Central Asian "Hu" women were stereotyped as barmaids or dancers by Han in China. Occasionally, "Hu" women would be involved in prostitution as the "Hu" women in China were at times in occupations that doubled as illicit services.[36]

During the short Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms period, Luoyang was the capital of the Later Liang (only for a few years before the court moved to Kaifeng) and Later Tang dynasty.

Later history[edit]

During the North Song dynasty, Luoyang was the 'Western Capital' and birthplace of Zhao Kuangyin, the founder of the Song dynasty. It served as a prominent cultural center, housing some of the most important philosophers. This prosperity was mainly caused by Luoyang undergoing new developments and reconstruction during this period.[7]

During the Jurchen Jin dynasty, Luoyang was the "Middle Capital".

Since the Yuan dynasty, Luoyang was no longer the capital of China in the rest of the ancient dynasties. During the Yuan and Ming dynasties, Luoyang was razed and rebuilt twice. Its walls were destroyed by peasant rebels in the late Ming period. The city walls were then rebuilt during the Qing dynasty.[7] The population was reduced to that of an average county. However, for one last time, Luoyang city was the capital of the Republic of China for a brief period of time during the Japanese invasion. By 1949, Luoyang's population was 75,000.

People's Republic of China[edit]

After the People's Republic of China was established, Luoyang was revived as a major heavy industrial hub. In the first five-year plan of China, 7 of 156 Soviet-aided major industrial programmes were launched in Luoyang's Jianxi District, including Dongfanghong Tractor Factory, Luoyang Mining Machines Factory and Luoyang Bearing Factory. Later, during the Third Front construction, a group of heavy industry factories was moved to or founded in Luoyang, including Luoyang Glass Factory. Industrial development significantly shifted Luoyang's demographic makeup, and about half of Luoyang's population are new immigrants after 1949 from outside the province or their descendants.

UNESCO World Heritage Site[edit]

- Longmen Grottoes, added to the UNESCO World Heritage List in 2000[37]

- The Grand Canal – Huiluo Barn, Hanjia Barn, added to the UNESCO World Heritage List in 2014[38]

- Silk Roads – Han Wei Luoyang City Site, Dingding Gate Site of Sui Tang Luoyang City, Xin'an Hangu Guan Site, added to the UNESCO World Heritage List in 2014[39]

Ancient city sites[edit]

- Erlitou Site (Zhenxun) of Xia dynasty

- Yanshi Shang City Site (Xibo) of Shang dynasty

- Wangcheng Site of Eastern Zhou dynasty

- Luoyang City Site of Han and Wei dynasty

- Luoyang City Site of Sui and Tang dynasty

Administrative divisions[edit]

The prefecture-level city of Luoyang administers 7 districts and 7 counties:

- Districts

- Defunct District

- Jili District, now part of Mengjin District

- Counties

During the 2010 census, the 5 "built-up" urban districts held a population of 1,857,003, making it the fourth-largest city in Henan. The entire area of Luoyang's municipal government held 6,549,941 inhabitants total.

| Map |

|---|

2021 administrative reorganization[edit]

With the 2017 designation of Zhengzhou as a National Central City, Henan Province in 2020 proposed a new development plan for Zhengzhou Metropolitan Area, which called for the development of Luoyang as a sub-central city. As part of this development, authorities decided to expand the urban area of Luoyang. This not only facilitated planning and coordinated use of resources and infrastructure in Luoyang, but also allowed for better integration towards Zhengzhou, as Yanshi, Jili and Mengjin previously separated the Luoyang urban area from Zhengzhou.[40]

On 28 March 2021, the central government approved a major administrative reorganization of Luoyang city. Yanshi City was reorganized into an urban district (Yanshi District), while Jili District and Mengjin County were merged into Mengjin District. This reorganization effectively doubled the urban area of Luoyang.[40]

Geography[edit]

As its name states, the Old Town of Luoyang is located on the north bank of the Luo, a southern tributary of the middle reaches of the Yellow River. The districts of the modern urban center include both banks and some of the surrounding mountains.

The countryside controlled by the municipal government includes still more rugged land: mountains comprise 45.51% of the total area; hills, 40.73%; and plains, 13.8%.[41]

Climate[edit]

Luoyang has a highly continental dry-winter humid subtropical climate (Köppen climate classification: Cwa).

| Climate data for Luoyang (1981–2010 normals, extremes 1951–2000) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 22.2 (72.0) |

24.3 (75.7) |

31.2 (88.2) |

35.5 (95.9) |

40.6 (105.1) |

44.2 (111.6) |

41.9 (107.4) |

41.7 (107.1) |

38.2 (100.8) |

34.8 (94.6) |

27.0 (80.6) |

23.5 (74.3) |

44.2 (111.6) |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 5.3 (41.5) |

8.4 (47.1) |

13.8 (56.8) |

21.5 (70.7) |

26.8 (80.2) |

31.0 (87.8) |

30.9 (87.6) |

29.3 (84.7) |

25.6 (78.1) |

20.5 (68.9) |

13.6 (56.5) |

7.4 (45.3) |

19.5 (67.1) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | −3.8 (25.2) |

−0.9 (30.4) |

3.6 (38.5) |

10.0 (50.0) |

15.2 (59.4) |

20.0 (68.0) |

22.3 (72.1) |

21.2 (70.2) |

16.5 (61.7) |

10.8 (51.4) |

3.8 (38.8) |

−1.9 (28.6) |

9.7 (49.5) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −17.4 (0.7) |

−18.2 (−0.8) |

−9.1 (15.6) |

−3.6 (25.5) |

4.4 (39.9) |

12.2 (54.0) |

16.5 (61.7) |

13.5 (56.3) |

6.9 (44.4) |

−2.3 (27.9) |

−8.6 (16.5) |

−14.9 (5.2) |

−18.2 (−0.8) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 8.2 (0.32) |

12.9 (0.51) |

25.4 (1.00) |

31.1 (1.22) |

57.5 (2.26) |

64.6 (2.54) |

138.5 (5.45) |

100.2 (3.94) |

84.2 (3.31) |

43.4 (1.71) |

20.9 (0.82) |

7.8 (0.31) |

594.7 (23.39) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.1mm) | 3.5 | 5.1 | 6.2 | 7.0 | 6.9 | 8.0 | 12.2 | 10.7 | 9.4 | 7.8 | 5.0 | 3.4 | 85.2 |

| Source 1: National Meteorological Center of CMA[42] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: Weather China (precipitation days 1971–2000)[43] data.ac.cn[44] | |||||||||||||

Culture[edit]

- Sites

The Longmen Grottoes south of the city were listed on the UNESCO list of World Heritage Sites in November 2000. Guanlin—a series of temples built in honor of Guan Yu, a hero of the Three Kingdoms period—is nearby. The White Horse Temple is located 12 km (7.5 mi) east of the modern town.

The Luoyang Museum (established 1958) features ancient relics dating back to the Xia, Shang, and Zhou dynasties. The total number of exhibits on display is 1,700.[45] China's only tomb museum, the Luoyang Ancient Tombs Museum, opened to the public in 1987 and is situated north of the modern town.

The Gaocheng Astronomical Observatory (also known as the Dengfeng Observatory or the Tower of Chou Kong) stands 80 km (50 mi) south-east of Luoyang. It was constructed in 1276 during the Yuan dynasty by Guo Shoujing as a giant gnomon for "the measurement of the sun's shadow". Prior to the Jesuit China Missions, it was used for establishing the summer and winter solstices in traditional Chinese astronomy.[46]

Luoyang is the foundation of Confucianism, the birth of Taoism, the first transmission of Buddhism, the formation of metaphysics, and the origin of neo-Confucianism. All kinds of cultural thoughts are integrated and symbiosis here, and the compass, paper making and printing among the four great inventions of ancient China were born here. Luoyang is also the cultural root and ancestral lineage of the global Chinese, more than 100 million Hakka ancestral home in the world, 70% of China's clan name originated here, Heluo culture represented by "Hetu Luoshu" is the ancestral source of Chinese civilization.[47]

- Cuisine

Water Banquet, which is one of the famous banquets passed on for generations in the history of Chinese cuisine, consists of 8 cold and 16 warm dishes all cooked in various broths, gravies, or juices. The water here has two meanings: one is that all the hot dishes have soup-tang soup water; the other is that each dish is served after another smoothly just like flowing water. It comprises a wide selection of ingredients, simple and versatile, diverse tastes, sour, spicy, sweet and salty, comfortable and delicious.

- Botany

Luoyang is also celebrated for the cultivation of peonies, its city flower. Since 1983, each mid-April the city hosts the Peony Culture Festival of Luoyang. More than 19 million tourists visited Luoyang during the 2014 festival.[48]

- Music

"Spring in Luoyang" (洛阳春; Luòyáng Chūn), an ancient Chinese composition, became popular in Korea during the Goryeo dynasty (918–1392) and is still performed in its dangak (Koreanized) version Nakyangchun (낙양춘). Lou Harrison, an American composer, has also created an arrangement of the work.

- Dialect

Residents of Luoyang typically speak a dialect of Zhongyuan Mandarin. Although Luoyang's dialect was a prestige dialect of spoken Chinese from the Warring States period of the Zhou until the Ming dynasty, it differs from the Beijing form of Mandarin which became the basis of the standard modern dialect.

- Outer space

Asteroid (239200) 2006 MD13 is named after Luoyang.

Education[edit]

- Luoyang Institute of Science and Technology (洛阳理工学院)

- Henan University of Science and Technology (河南科技大学)

- Luoyang Normal University (洛阳师范学院)

- PLA Foreign Language Institute, formerly known as the Luoyang PLA College of Foreign Languages (解放军洛阳外语学院)

Transportation[edit]

The city can be reached by highways, trains or planes. Long-distance buses are also an option although they generally tend to take longer. High-speed rail is the most common way to get into the city from either Xi'an or Zhengzhou. Luoyang has a bus system of around 30+ lines. Taxis are also a common sight in the city.

Subway[edit]

Line 1 of Luoyang Subway opened 28 March 2021.[49] Line 2 opened on 26 December 2021.

Rail[edit]

- Conventional speed

The main station for conventional rail services is Luoyang railway station on the Longhai railway. Guanlin railway station on the Jiaozuo–Liuzhou railway has a far less frequent service, only seeing north–south trains or vice versa that don't stop at Luoyang railway station.

- high-speed

Luoyang Longmen railway station sees high-speed services on the Zhengzhou–Xi'an high-speed railway.

Road[edit]

- G30 Lianyungang–Khorgas Expressway

- G36 Nanjing–Luoyang Expressway

- G55 Erenhot–Guangzhou Expressway

- China National Highway 207

- China National Highway 310

Air[edit]

Luoyang is served by Luoyang Beijiao Airport.

Twin towns and sister cities[edit]

Luoyang is twinned with:

La Crosse, Wisconsin, United States

La Crosse, Wisconsin, United States Okayama, Okayama, Japan

Okayama, Okayama, Japan

Famous residents[edit]

- Laozi, legendary founder of Taoism

- The emperors of the Eastern Zhou dynasty

- Guiguzi, geomancer and numerologist

- The emperors of the Eastern Han dynasty

- Xuanzang, Buddhist monk and hero of the Journey to the West

- Liu Yuxi, poet

- Emperor Taizu of Song, founder of the Song dynasty

- Gao Hong, pipa player

- Du Wei, soccer player

- Wang Yibo, actor, singer, idol

- Chen Dong, astronaut of Shenzhou 11 and Shenzhou 14

- Meng Meiqi, singer, dancer (WJSN and Rocket Girls 101)

See also[edit]

- List of twin towns and sister cities in China

- Historical capitals of China

- Luoyang Longmen railway station

- Sino-Roman Relations

- Silk Road transmission of Buddhism

- Roman Catholic Diocese of Luoyang

- Joraku

References[edit]

- ^ a b "China: Hénán (Prefectures, Cities, Districts and Counties) - Population Statistics, Charts and Map". www.citypopulation.de.

- ^ 河南省统计局、国家统计局河南调查总队 (November 2017). 《河南统计年鉴-2017》. 中国统计出版社. ISBN 978-7-5037-8268-8. Archived from the original on 2018-11-15. Retrieved 2018-12-03.

- ^ "河南统计年鉴—2017". www.ha.stats.gov.cn. Archived from the original on 2018-11-15. Retrieved 2018-12-03.

- ^ "洛阳市2022年国民经济和社会发展统计公报". www.ly.gov.cn. Retrieved 2023-10-30.

- ^ "Far East Kingdoms". Early Chinese Cultures. Retrieved 24 January 2020.

- ^ China.org.cn, 2009

- ^ a b c d Schellinger, Paul; Salkin, Robert, eds. (1996). International Dictionary of Historic Places, Volume 5: Asia and Oceania. Chicago: Fitzroy Dearborn Publishers. pp. 538–541. ISBN 1-884964-04-4.

- ^ Robert Hymes (2000). John Stewart Bowman (ed.). Columbia Chronologies of Asian History and Culture. Columbia University Press. p. 13. ISBN 978-0-231-11004-4.

- ^ de Crespigny, Rafe (2017). Fire over Luoyang: A History of the Later Han Dynasty 23–220 AD. Leiden: Brill. pp. 16–52. ISBN 9789004324916.

- ^ Hill (2009), p. 27.

- ^ Hill (2009), p. xvi,

- ^ Cullen, Christopher (2017). Heavenly Numbers: Astronomy and Authority in Early Imperial China. New York: Oxford University Press. p. 336. ISBN 9780198733119; Twitchett, Denis Crispin; Loewe, Michael, eds. (1986). The Cambridge History of China. Volume 1: The Ch'in and Han Empires, 221 B.C.-A.D. 220. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. p. 348. ISBN 9780521243278.

- ^ a b Graff, David A. (2002). Medieval Chinese Warfare. 300 - 900. Routledge. p. 50.

- ^ Grousset, Rene (1970). The Empire of the Steppes. Rutgers University Press. pp. 56–57. ISBN 0-8135-1304-9.

- ^ Sims-Williams, N. (December 15, 1985). "ANCIENT LETTERS". Encyclopædia Iranica. Vol. II. pp. 7–9.

- ^ Keramidas, Kimon. "SOGDIAN ANCIENT LETTER II". NYU. Telling the Sogdian Story: A Freer/Sackler Digital Exhibition Project.

- ^ "The Sogdian Ancient Letters 1, 2, 3, and 5". Silk Road Seattle - University of Washington. translated by Prof. Nicholas Sims-Williams.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ Norman, Jeremy. "Aurel Stein Discovers the Sogdian "Ancient Letters" 313 CE to 314 CE". History of Information.

- ^ Sogdian Ancient Letter No. 3. Reproduced from Susan Whitfield (ed.), The Silk Road: Trade, Travel, War and Faith (2004) p. 248.

- ^ "Ancient Letters". THE SOGDIANS Influencers on the Silk Roads. Freer Gallery of Art and Arthur M. Sackler Gallery, Smithsonian Institution.

- ^ Keramidas, Kimon. "SOGDIAN ANCIENT LETTER III: LETTER TO NANAIDHAT". NYU. Telling the Sogdian Story: A Freer/Sackler Digital Exhibition Project.

- ^ "Sogdian letters". ringmar.net. History of International Relations. 5 March 2021.

- ^ Vaissière, Étienne de la (2005). "CHAPTER TWO ABOUT THE ANCIENT LETTERS". Sogdian Traders: A History. Handbook of Oriental Studies. Section 8 Uralic & Central Asian Studies. Vol. 10. Brill. pp. 43–70. doi:10.1163/9789047406990_005. ISBN 978-90-47-40699-0.

- ^ Vaissière, Étienne de la (January 1, 2005). "About the Ancient Letters". Sogdian Traders. Brill. pp. 43–70. doi:10.1163/9789047406990_005. ISBN 9789047406990 – via brill.com.

- ^ Livšic, Vladimir A. (2009). "SOGDIAN "ANCIENT LETTERS" (II, IV, V)". In Orlov, Andrei; Lourie, Basil (eds.). Symbola Caelestis: Le symbolisme liturgique et paraliturgique dans le monde chrétien. Piscataway: Gorgias Press. p. 344-352. ISBN 9781463222543.

- ^ Graff, David A. (2002). Medieval Chinese Warfare 300 - 900. Routledge. p. 58.

- ^ a b Graff, David A. (2002). Medieval Chinese Warfare, 300 - 900. Routledge. p. 98.

- ^ Graff, David A. (2002). Medieval Chinese Warfare. Routledge. p. 103.

- ^ Marks, Robert B. (2011). China: Its Environment and History. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers. ISBN 978-1442212756. p. 116

- ^ Schinz, Alfred (1996). The Magic Square: Cities in Ancient China. Edition Axel Menges. ISBN 3930698021. p. 167-169.

- ^ 《资治通鉴·唐纪·唐纪二十》:辛亥,明堂成,高二百九十四尺,方三百尺。凡三层:下层法四时,各随方色。中层法十二辰;上为圆盖,九龙捧之。上层法二十四气;亦为圆盖,上施铁凤,高一丈,饰以黄金。中有巨木十围,上下通贯,栭栌棤藉以为本。下施铁渠,为辟雍之象。号曰万象神宫。

- ^ Abramson (2008), p. viii.

- ^ Morrow, Kenneth T. (May 2019). Negotiating Belonging: The Church of the East's Contested Identity in Tang China (PDF) (PhD thesis). University of Texas at Dallas. pp. 109–135, viii, xv, 156, 164, 115, 116.

- ^ Morrow, Kenneth T. (May 2019). Negotiating Belonging: The Church of the East's Contested Identity in Tang China (PDF) (PhD thesis). University of Texas at Dallas. pp. 155–156, 149, 150, viii, xv.

- ^ Morrow, Kenneth T. (May 2019). Negotiating Belonging: The Church of the East's Contested Identity in Tang China (PDF) (PhD thesis). p. 164.

- ^ Abramson, Marc S. (2011). Ethnic Identity in Tang China. Encounters with Asia. University of Pennsylvania Press. p. 20. ISBN 978-0812201017.

- ^ "Longmen Grottoes".

- ^ "The Grand Canal".

- ^ "Silk Roads: The Routes Network of Chang'an-Tianshan Corridor".

- ^ a b "河南洛阳扩容,撤县设区还香吗?". 28 March 2021.

- ^ 洛阳市人民政府网站 [Luòyángshì Rénmín Zhèngfǔ Wǎngzhàn, Luoyang Municipal People's Government Website] op. cit. 北京2008年奥运火炬接力官方网站 [Běijīng 2008 Nián Àoyùn Huǒjù Jiēlì Guānfāng Wǎngzhàn, Beijing 2008 Torch Relay Official Website]. 〈洛阳地理及气候概况〉 ["Luòyáng Dìlǐ Jí Qìhòu Gàikuàng", "Overview of Luoyang's Geography and Climate"]. 20 Mar 2008. Accessed 16 Jan 2014. (in Chinese)

- ^ 1981年-2010年(洛阳)月平均气温和降水 (in Simplified Chinese). National Meteorological Center of CMA. Retrieved 27 November 2022.

- ^ 洛阳 – 气象数据 – 中国天气网. weather.com.cn. Retrieved 2018-08-08.

- ^ 气候资源数据库. data.ac.cn. 2018-08-08.

- ^ China Culture. "Luoyang Museum Archived 2016-02-15 at the Wayback Machine".

- ^ Needham, Joseph. Science and Civilisation in China.

- ^ "基本概况". www.ly.gov.cn. Retrieved 2023-10-30.

- ^ "河南频道_凤凰网". hn.ifeng.com. Retrieved 2023-10-30.

- ^ "官宣!洛阳地铁1号线3月28日开通 中西部非省会城市第一个". 2021-03-26.

Further reading[edit]

- Abramson, Marc. Ethnic Identity in Tang China. University of Pennsylvania Press (Philadelphia), 2008. ISBN 978-0-8122-4052-8.

- Cotterell, Arthur. The Imperial Capitals of China: An Inside View of the Celestial Empire. Pimlico (London), 2008. ISBN 978-1-84595-010-1.

- Hill, John E. Through the Jade Gate to Rome: A Study of the Silk Routes during the Later Han Dynasty, 1st to 2nd Centuries CE. BookSurge (Charleston), 2009. ISBN 978-1-4392-2134-1.

- Jenner, W. J. Memories of Loyang. Clarendon Press (Oxford), 1981.

- Yang Hsüan-chih. Lo-yang ch'ien-lan chi, translated by Wang Yi-t'ung as A Record of Buddhist Monasteries in Lo-yang. Princeton University Press (Princeton), 1984. ISBN 0-691-05403-7.

External links[edit]

- Official website of the Luoyang Municipal Government (in Chinese)

- "Wangcheng Park in Luoyang" at China.org