Nāgārjuna

Nāgārjuna (Devanagari:नागार्जुन, Telugu: నాగార్జున, Tibetan: ཀླུ་སྒྲུབ་ klu sgrub, Chinese: 龍樹, Sinhala නාගර්පුන) (ca. 150–250 CE) was an important Buddhist teacher and philosopher. Along with his disciple Āryadeva, he is credited with founding the Madhyamaka school of Mahāyāna Buddhism. Nāgārjuna is credited with developing the philosophy of the Prajñāpāramitā Sūtras—even, in some sources, with having (re)revealed these scriptures in the world, having recovered them from the realm of the nāga-s (snake/dragon spirits)—and is also sometimes associated with the Buddhist university of Nālandā.

History

Very little is reliably known of the life of Nāgārjuna, since the surviving accounts were written in Chinese and Tibetan, centuries after his death. According to some accounts, Nāgārjuna was originally from Southern India. Some scholars believe that Nāgārjuna was an advisor to a king of the Sātavāhana Dynasty. Archaeological evidence at Amarāvatī indicates that if this is true, the king may have been Yajña Śrī Śātakarṇi, who ruled between 167 and 196 CE. On the basis of this association, Nāgārjuna is conventionally placed at around 150–250 CE.

According to a 4th/5th-century biography translated by Kumārajīva, Nāgārjuna was born into a Brahmin family, and later became a Buddhist.

Some sources claim that Nāgārjuna lived on the mountain of Śrīparvata in his later years, near the city that would later be called Nāgārjunakoṇḍa ("Hill of Nāgārjuna"). Nāgārjunakoṇḍa was located in what is now the Nalgonda/ Guntur district of Andhra Pradesh. The Caitika and Bahuśrutīya nikāyas are known to have had monasteries in Nāgārjunakoṇḍa.

Writings

There exist a number of influential texts attributed to Nāgārjuna though, as there are many pseudepigrapha attributed to him, lively controversy exists over which are his authentic works. The only work that all scholars agree is Nagarjuna's is the Mūlamadhyamakakārikā (Fundamental Verses on the Middle Way), which contains the essentials of his thought in twenty-seven chapters.

According to one view, that of Christian Lindtner, the works definitely written by Nagarjuna are:

- Mūlamadhyamaka-kārikā (Fundamental Verses of the Middle Way)

- Śūnyatāsaptati (Seventy Verses on Emptiness)

- Vigrahavyāvartanī (The End of Disputes)

- Vaidalyaprakaraṇa (Pulverizing the Categories)

- Vyavahārasiddhi (Proof of Convention)

- Yuktiṣāṣṭika (Sixty Verses on Reasoning)

- Catuḥstava (Hymn to the Absolute Reality)

- Ratnāvalī (Precious Garland)

- Pratītyasamutpādahṝdayakārika (Constituents of Dependent Arising)

- Sūtrasamuccaya

- Bodhicittavivaraṇa (Exposition of the Enlightened Mind)

- Suhṛllekha (Letter to a Good Friend)

- Bodhisaṃbhāra (Requisites of Enlightenment)

In addition to the above, there are many other works attributed to Nāgārjuna, and lively controversy over which are authentic. In particular, several important works of esoteric Buddhism (most notably the Pañcakrama or "Five Stages") are attributed to Nāgārjuna and his disciples. Contemporary research suggests that these works are datable to a significantly later period in Buddhist history (late eighth or early ninth century), but the tradition of which they are a part maintains that they are the work of the Madhyamaka Nāgārjuna and his school. Traditional historians (for example, the 17th century Tibetan Tāranātha), aware of the chronological difficulties involved, account for the anachronism via a variety of theories, such as the propagation of later writings via mystical revelation. A useful summary of this tradition, its literature, and historiography may be found in Wedemeyer 2007.

Lindtner considers that the Māhaprajñāparamitopadeśa, a huge commentary on the Large Prajñāparamita, not to be a genuine work of Nāgārjuna. This work is only attested in a Chinese translation by Kumārajīva.There is much discussion as to whether this is a work of Nāgārjuna, or someone else. Étienne Lamotte, who translated one third of the work into French, felt that it was the work of a North Indian bhikṣu of the Sarvāstivāda school, who later became a convert to the Mahayana. The Chinese scholar-monk Yin Shun felt that it was the work of a South Indian, and that Nāgārjuna was quite possibly the author. Actually, these two views are not necessarily in opposition, and a South Indian Nāgārjuna could well have studied in the northern Sarvāstivāda. Neither of the two felt that it was composed by Kumārajīva which others have suggested.

Philosophy

From studying his writings, it is clear that Nāgārjuna was conversant with many of the Śrāvaka philosophies and with the Mahāyāna tradition. However, determining Nāgārjuna's affiliation with a specific Nikaya is difficult, considering much of this material is presently lost. If the most commonly accepted attribution of texts (that of Christian Lindtner) holds, then he was clearly a Māhayānist, but his philosophy holds assiduously to the Śrāvaka canon, and while he does make explicit references to Mahāyāna texts, he is always careful to stay within the parameters set out by the Śrāvaka canon.

Nagarjuna may have arrived at his positions from a desire to achieve a consistent exegesis of the Buddha's doctrine as recorded in the āgamas. In the eyes of Nagarjuna the Buddha was not merely a forerunner, but the very founder of the Madhyamaka system. David Kalupahana sees Nagarjuna as a successor to Moggaliputta-Tissa in being a champion of the middle-way and a reviver of the original philosophical ideals of the Buddha.

Sunyata

Nāgārjuna's primary contribution to Buddhist philosophy is in the use of the concept of śūnyatā, or "emptiness," which brings together other key Buddhist doctrines, particularly anātman (no-self) and pratītyasamutpāda (dependent origination), to refute the metaphysics of Sarvastivāda and Sautrāntika (extinct non-Mahayana schools). For Nāgārjuna, as for the Buddha in the early texts, it is not merely sentient beings that are "selfless" or non-substantial; all phenomena are without any svabhāva, literally "own-being" or "self-nature", and thus without any underlying essence. They are empty of being independently existent; thus the heterodox theories of svabhāva circulating at the time were refuted on the basis of the doctrines of early Buddhism. This is so because all things arise always dependently: not by their own power, but by depending on conditions leading to their coming into existence, as opposed to being.

Two truths

Nāgārjuna was also instrumental in the development of the two truths doctrine, which claims that there are two levels of truth or reality in Buddhist teaching, the ultimate reality (paramārtha satya) and the conventionally or superficial reality (saṃvṛtisatya).

In articulating this notion, Nāgārjuna drew on an early source in the Kaccāyanagotta Sutta, which distinguishes definitive meaning (nītārtha) from interpretable meaning (neyārtha):

- By and large, Kaccayana, this world is supported by a polarity, that of existence and non-existence. But when one reads the origination of the world as it actually is with right discernment, 'non-existence' with reference to the world does not occur to one. When one reads the cessation of the world as it actually is with right discernment, 'existence' with reference to the world does not occur to one.

- By and large, Kaccayana, this world is in bondage to attachments, clingings (sustenances), and biases. But one such as this does not get involved with or cling to these attachments, clingings, fixations of awareness, biases, or obsessions; nor is he resolved on 'my self.' He has no uncertainty or doubt that just stress, when arising, is arising; stress, when passing away, is passing away. In this, his knowledge is independent of others. It's to this extent, Kaccayana, that there is right view.

- "'Everything exists': That is one extreme. 'Everything doesn't exist': That is a second extreme. Avoiding these two extremes, the Tathagata teaches the Dhamma via the middle..."

Relativity

Nagarjuna also taught the idea of relativity; in the Ratnāvalī, he gives the example that shortness exists only in relation to the idea of length. The determination of a thing or object is only possible in relation to other things or objects, especially by way of contrast. He held that the relationship between the ideas of "short" and "long" is not due to intrinsic nature (svabhāva). This idea is also found in the Pali Nikāyas and Chinese Āgamas, in which the idea of relativity is expressed similarly: "That which is the element of light ... is seen to exist on account of [in relation to] darkness; that which is the element of good is seen to exist on account of bad; that which is the element of space is seen to exist on account of form."[12]

Nagarjuna as Ayurvedic physician

According to Frank John Ninivaggi, Nagarjuna was also a practitioner of Ayurveda, or traditional Indian Ayurvedic medicine. First described in the Sanskrit medical treatise entitled Sushruta Samhita (of which he was the compiler of the redaction), many of his conceptualizations, such as his descriptions of the circulatory system and blood tissue (described as rakta dhātu) and his pioneering work on the therapeutic value of specially treated minerals knowns as bhasmas, which earned him the title of the "father of iatrochemistry.

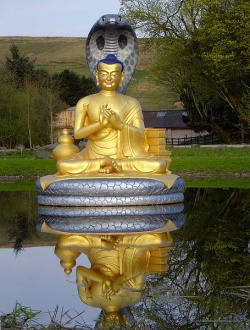

Iconography

Nāgārjuna is often depicted in composite form comprising human and naga characteristics. Often the naga aspect forms a canopy crowning and shielding his human head. The notion of the naga is found throughout Indian religious culture, and typically signifies an intelligent serpent or dragon, who is responsible for the rains, lakes and other bodies of water. In Buddhism, it is a synonym for a realized arhat, or wise person in general. The term also means "elephant".

English translations

Mulamadhyamakakarika

See also: Mulamadhyamakakarika

Other works

| Author | Title | Publisher | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Loizzo, Joseph | Nagarjuna's Reason Sixty (Yuktisastika) with Candrakirti's Commentary (Yuktisastikavrrti) | Columbia University Press, 2007 | Standing midway between his other masterpieces on philosophy and religion, in the Reason Sixty Nagarjuna describes the central thrust of his therapeutic philosophy of language - the elimination of cognitive bias and affective resistances to the gradual cultivation of nondualistic wisdom and compassion. |

| Kawamura, L. | Golden Zephyr | Dharma, 1975 | Translation of the Suhrlekkha with a Tibetan commentary |

| Bhattacharya, Johnston and Kunst | The Dialectical Method of Nagarjuna | Motilal, 1978 | A superb translation of the Vigrahavyavartani |

| Lindtner, C. | Master of Wisdom: Writings of the Buddhist Master Nāgārjuna | Dharma, 1986 | An excellent introduction to Madhyamika, Master of Wisdom contains two hymns of praise to the Buddha, two treatises on Shunyata, and two works that clarify the connection of analysis, meditation, and moral conduct. Includes Tibetan verses in transliteration and critical editions of extant Sanskrit.

Tibetan Translation (product ID: 0-89800-286-9) |

| Lindtner, C. | Nagarjuniana | Motilal, 1987 [1982] | Contains Sanskrit or Tibetan texts and translations of the

Shunyatasaptati, Vaidalyaprakarana, Vyavaharasiddhi (fragment), Yuktisastika, Catuhstava and Bodhicittavivarana. A translation only of the Bodhisambharaka. The Sanskrit and Tibetan texts are given for the Vigrahavyavartani. In addition a table of source sutras is given for the Sutrasamuccaya. |

| Komito, D. R. | Nagarjuna's "Seventy Stanzas" | Snow Lion, 1987 | Translation of the Shunyatasaptati with Tibetan commentary |

| Tola, Fernando and Carmen Dragonetti | Vaidalyaprakarana | South Asia Books, 1995 | |

| Jamieson, R. C. | Nagarjuna's Verses on the Great Vehicle

and the Heart of Dependent Origination |

D.K., 2001 | Translation and edited Tibetan of the Mahayanavimsika and the Pratityasamutpadahrdayakarika, including work on texts from the cave temple at Dunhuang, Gansu, China |

| Hopkins, Jeffrey | Nagarjuna's Precious Garland: Buddhist Advice for Living and Liberation | Snow Lion Publications, 2007 | |

| Brunnholzl, Karl | In Praise of Dharmadhatu | Snow Lion Publications, 2008 | Translation with commentary by the 3rd Karmapa |

| Jones, Richard | Nagarjuna: Buddhism's Most Important Philosopher | Booksurge, 2010 | Translation into plain English with commentaries of the Mulamadhyamikakarikas, the Vigrahavyavartani with Nagarjuna's commentary, and part of the Ratnavali. |

References