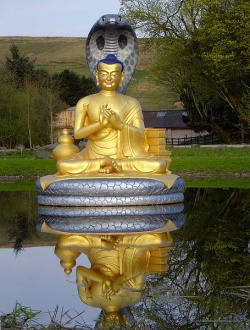

Nāgārjuna — the second buddha

Acharya Nagarjuna (slob dpon klu sgrub). A great Indian master of philosophy. He was named "Naga Master" because he taught the beings in the naga world and returned with the extensive version of Prajnaparamita left in their safe keeping. [RY]

klu grub - Nagarjuna, a great Indian Buddhist master and the chief expounder of Madhyamaka philosophy [RY]

klu grub - Nagarjuna. An Indian master of philosophy and a tantric sid dha. One of the Eight Vidyadharas; receiver of the tantras of Lotus Speech such as Supreme Steed Display. He is said to have taken birth in the southern part of India around four hundred years after the Buddha's nirvana. Having received ordination at Nalanda Monastery, he later acted as preceptor for the monks. He knew alchemy, stayed alive for six hundred years and transformed ordinary materials into gold in order to sustain the sangha. At Bodhgaya he erected pillars and stone walls to protect the Bodhi Tree and constructed 108 stupas. From the realm of the nagas he brought back the extensive Prajnaparamita scriptures (for example the 'The Perfection of Wisdom in 25,000 Lines {or, Verses}). He was the life pillar for the Mahayana, but specifically he was a major exponent of the Unexcelled Vehicle of Vajrayana. Having attained realization of Hayagriva, he transmitted the lineage to Padmasambhava [RY]

Works

The South-Indian sage and philosopher Nāgārjuna was pivotal to the growth of Mahāyāna Buddhism, and, even more than Siddhattha Gotama, is the subject of rich mythology . Known as The Second Buddha, he lived about six centuries after Gotama. His writings form the basis of Mādhyamika philosophy, on which Tibetan tantrism is based. Legend has it that he retrieved the Mahayana sutras, lost shortly after Gotama’s death, from the subterranean world of the nāgas (a snake kingdom); hence his name.

Nāgārjuna elaborated three key teachings: prajñāpāramitā, (the trancendance of wisdom), śūnyatā (emptiness) and pratītyasamutpāda (dependent origination). By referring closely to the Mahāyāna sutras and maintaining a broad compatibility with early Buddhism, he gained a widespread following that to this day constitutes the principal schism in the Buddhist world, between Northern and Southern Buddhists.

The Southern school refers to itself as the Theravāda, teachings of the Elders, and is also called Hīnayāna, the lesser vehicle, by the Northern school (Mahāyāna means greater vehicle). Although this occasionally creates ill feeling, the distinction is generally held to be philosophical rather than qualitative — mahāyāna shifts the primary focus of Buddhist practice from personal liberation to the full awakening of all sentient beings. Also, Nāgārjuna’s core teaching is the emptiness (śūnyatā) of all phenomena, as opposed to early Buddhist emphasis on non-self (anātman). The philosophies are compatible, but the mahāyāna scope is broader, hence greater vehicle.

The Southern (Theravada) school of Buddhism accepts only the Pali Canon as authentic teachings of the historical Buddha.

On a less religious note, Thomas McEvilley’s groundbreaking book The Shape of Ancient Thought traces parallels and probable exchanges between Greek and Indian philosophy, in particular by Sextus Empiricus who, like Nāgārjuna, advised that we should suspend judgment about virtually all beliefs.

Nāgārjuna is famous for such uncompromising paradoxes as “Samsâra equals nirvana,” (entrapment equals freedom), R.C. Jamieson says about them:

“At first sight, The Perfection of Wisdom is bewildering, full of paradox and apparent irrationality. Yet once one accepts that trying to unravel these texts without experiencing the intuitions behind them is not satisfactory, it becomes clear that paradox and irrationality are the only means of conveying to the reader those underlying intuitions that would otherwise be impossible to express.” (The Perfection of Wisdom NY : Penguin Viking, 2000. ISBN 0-670-88934-2 pp. 8)