Notes on the Verses by Shen-hsiu and Hui-neng

According to the Platform Sutra:

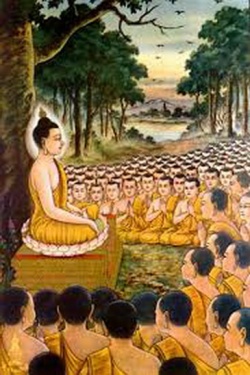

Hung-jen, the Fifth Patriarch, the Enlightened Master

Shen-hsiu, the Learned Senior Monk, experienced in gradual meditation

Hui-neng, the illiterate woodcutter from the barbarian south, suddenly enlightened

1) Shen-hsiu presents the following verse which Hung-jen characterizes as incomplete in understanding.

The body is the bodhi tree,

The mind is like a clear mirror.

At all times we must strive to polish it,

And must not let the dust collect.

(Yampolsky 130)

This can be understood as advocating a gradual process of achieving and maintaining the purity and clarity of the mirror-like mind, the mind of emptiness or empty awareness, of the oneness of reality. The emphasis is on the form of practice required of the body and the mind to cultivate and sustain this awareness.

2) Hui-neng offers the following alternative verse:

Bodhi originally has no tree,

The mirror(-like mind) has no stand.

Buddha-nature (emptiness/oneness) is always clean and pure;

Where is there room for dust (to alight)?

(Yampolsky 132)

This can be understood as advocating the sudden awakening to emptiness/oneness. The emphasis is on realizing emptiness beyond form all-at-once, instantaneously, in the here-and-now (in the moment of reading the verse).

3) Another edition of the Platform Sutra attributes the following verse to Hui-neng:

The mind is the Bodhi tree,

The body is the mirror stand.

The mirror is originally clean and pure;

Where can it be stained by dust?

(Yampolsky 132)

This appears to be a kind of combination (although not exact) of the first two lines of Shen-hsiu's verse and the last two lines of first version of Hui-neng's verse. The first half is form and the last half expresses emptiness. One must realize emptiness in the world of form, and the true nature of form is emptiness. However, one must realize emptiness in this very moment, not see it as something that one strives to achieve or keep in the future.

Hui-neng, the illiterate woodcutter who comes from outside of the rigid hierarchical structure of gradual meditation practices, achieves the instantaneous awareness of the oneness of all reality in the here-and-now. Nevertheless, he inherits the religious authority of the Fifth Patriarch Hung-jen and eventually becomes the Sixth Patriarch, the head of the Chan/Zen Buddhist order in China.

Philip Yampolsky

Dating back to the eighth century C.E., the Platform Sūtra of the Sixth Patriarch is a foundational text of Chan/Zen Buddhism that reveals much about the early evolution of Chinese Chan and the ideological origins of Japanese Zen and Korean Sŏn. Purported to be the recorded words of the famed Huineng, who was understood to be the Sixth Patriarch of Chan and the father of all later Chan/Zen Buddhism, the Platform Sūtra illuminates fundamental Chan Buddhist principles in an expressive sermon that describes how Huineng overcame great personal and ideological challenges to uphold the exalted lineage of the enlightened Chan patriarchs while realizing the ultimate Buddhist truth of the original, pure nature of all sentient beings.

Huineng seems to reject meditation, the value of good karma, and the worship of the buddhas, conferring instead a set of “formless precepts” on his audience, marked by embedded notes in the text. In his central message, an inherent, perfect buddha nature stands as the original true condition of all sentient beings, which people of all backgrounds can experience for themselves. Philip Yampolsky’s masterful translation contains extensive explanatory notes and an edited, amended version of the Chinese text. His introduction critically considers the background and historical setting of the work and locates Huineng’s place within the history and legends of Chan Buddhism. This new edition features a foreword by Morten Schlütter further situating the Platform Sūtra within recent historical research and textual evidence, and an updated glossary that includes the modern pinyin system of transcription.

About the Author

Philip B. Yampolsky (1920–1996) was professor of East Asian languages and cultures and director of the C. V. Starr East Asian Library at Columbia University. An eminent translator and scholar of Zen Buddhist texts, he edited Letters of Nichiren and Selected Writings of Nichiren and translated The Zen Master Hakuin: Selected Writings. Morten Schlütter is an associate professor at the University of Iowa. He is the author of How Zen Became Zen: The Dispute Over Enlightenment and the Formation of Chan Buddhism in Song-Dynasty China and coeditor, with Stephen F. Teiser, of Readings of the Platform Sūtra.