On equivalencies and a new dharma center…

Lately I find myself reflecting on equivalence. Yet before I share my thoughts I would like to dedicate this blog post to Lizette, a hospice resident that I had visited who died yesterday. May her experience of the bardo be one of restful ease!

As a chaplain the notion of the possibility of equivalence helps to bridge the differences between myself and others- between what might be expressed, or needed, by someone other than myself. Ascertaining equivalence, a necessary act of juggling, forces us to examine our orthodoxies. It opens the door to the barn where we keep all of our sacred cows, our assumptions, and very often, all of the ways that we lazily forego really examining how we are with others, especially in relation to our larger belief systems, and all of the other spheres that we occupy. When I can find the points of connection that I share with people with whom one would assume there is no connection, I am usually left with an understanding of just how similar I am to others. Equivalence helps to reduce the promotion associated with self-elevation might make me say, “As a Buddhist, I am different from you in that I believe….”, or, “As a Vajrayana Buddhist I feel that my path is better because….”

The word equivalence has its root in the early 15th century middle French word equivalent, which is a conjunction of the prefix equi meaning equal, and valent (as in valence) and valiant, which at that time period referred to strength, bond, and a “combined power of an element“. I am reminded of the importance of valence electrons in chemistry and physics- specifically how the balance of electrical charges between atoms necessitate a sharing of electrons thus creating bonds between atoms. From these bonds everything around us arises; indeed, through the play of interdependence everything that we know can come into being.

I find this metaphor helpful as it involves stepping out of the traditional norms of Buddhist language. Of course, one might ask, “what language isn’t Buddhist?” In this question is a profound point. If our approach to Buddhist practice, whatever form that may take, or for example my chaplaincy informed by my practice of Buddhism, cannot interpenetrate other forms of language, other modalities of thought, or other creative models, it lacks the ability to maintain equivalency. In this manner it ends up lacking the ability to be itself while remaining fluid; it remains separated and isolated, at odds with whatever other it may encounter. In this way I know that I run the risk of falling into a discursive self vs. other perspective when I feel a lack of openness, fluidity, and ability to be at ease with whatever arises.

It can be easy to feel self-conscious within, and around, our belief system which if one is Buddhist, often undermines our very ability to be Buddhist. Indeed sometimes we try to be “Buddhist” as a way to distinguish oneself from others. This kind of separation is a terrible violence- an awful form of self-inflation and spiritual self-destruction that seems to miss the larger point.

And yet, if we explore the possibility that no language can be found that exists outside of the framework of Buddhism in its pure natural manner of expressing itself then it is easy to appreciate true natural arising equivalencies. We are no longer “Buddhist”, we just are, which I suspect was what Shakyamuni came to value within his spiritual quest.

Over the past two weeks I have had the fortune to visit two women who were actively dying at two different hospices in the New York City area. Two very different women, going through different experiences of similar processes: dying. Both of these women had strong spiritual paths- unique paths of self-taught wisdom borne through the constancy of the repeated trials and tribulations that only a full life can bring. In their own ways, as self-taught “outsiders” they were Christ-like, and Buddhistic, and spoke of pure a basic expansive being without necessarily referencing any particular Buddhist vocabulary. Indeed it appeared that the slow fading of the flickering flame of their life allowed them to rest in a peaceful alert awareness that was a real joy to experience. Here I was, a chaplain, asked to come visit these two women who in that moment expressed a depth of view that I could do nothing but rejoice in and admire. I left feeling very confident in their process- they were touching a nearly inexpressible beauty. The visits with both women were punctuated by long silences with much eye contact- with simply being together, with a basic human connection.

Language, with its structural intricacies, its variegated forms, and kaleidoscopic ability to transform, often acts as a buttress in relation to our habitual referential reactions. It allows for, and instills, comparison -creating an endless system of distinctions. A literary color wheel, language runs the risk of pinning everything around us down; leaving us with a sense of knowing. And yet I wonder, where and when, does knowing intersect with being- with the quiet awareness from just being? What is the nature of their relationship within us?

My experience with Lizette, one of the two hospice patients described above, was that whenever I tried to use language and vocabulary to capture what she told me that she was experiencing a clumsy formalism ensued. The beauty and power of her experience of being was made overly solid, overly distinct and “other” by trying to define it. The only thing that kept this feeling alive was to join with it; to sit with her; and to not “know” it, but to be it.

What is the difference between discerned knowledge and knowing borne from resting within the moment? Where, or perhaps more importantly, when, do our assumptions, our knowledge, or our better sense and logical mind of discernment (a deep and satisfying place of self-importance) get in the way of simple being? How does language and knowing try to contain the simple being that is needed to allow us to rest in all of the equivalencies around us?

I am currently working on establishing a Dharma center here in Brooklyn called New York Tsurphu Goshir Dharma Center. This center is the only center of His Eminence the 12th Goshir Gyaltsab Rinpoche, Regent of the Kamtsang Kagyu Lineage. Just yesterday we received our 501 c 3 status as a church! It is a great honor and joy to co-Found and Co-Direct a Dharma center headed by a mahasiddha, and amidst all of the uncertainty and fears of failure, or that this will be a complete disaster, I keep coming back to memories of ngondro and the trials that Milarepa, our not so distant father, underwent.

Rob Preece, in his book Preparing for Tantra: Creating the Psychological Ground for Practice, offers a compelling argument for equivalency as it arises between aspects of the hardship and challenge created by undergoing ngondro and other hardships that may share a contextual similarity. Preece describes how all of the work and hard physical labor that he put into helping to build a center that Lama Yeshe was establishing was a prime ground for focusing the mind around dharma practice, planting aspirational seeds that would doubtlessly blossom into mature trees that provide support, shelter and benefit for others. Indeed, I know that as I challenged my body by carrying hundreds of pounds of building materials, the back pain and discomfort of refinishing the floors in 100 degree heat lead me to feel closer to Milarepa than I have felt in a long time. The practice of demolishing old structures, hanging sheetrock and cutting my hands while rewiring the shrine room allowed me to appreciate Preece’s point that ngondro was a creation meant to challenge, to purify, and to create gravity around dharma practice. My seemingly small daily endeavors, in reality, connect me to my spiritual lineage which allows me to feel close to Naropa, Marpa and Milarepa.

Ngondro is one thing- a practice that I value and feel is too often treated as just a preliminary that is to be rushed through, but how is chaplaincy different? Can it be any different? When we really look, can there even ever be a difference?

Milarepa never did ngondro, nor did Naropa- they had the benefit of having their teachers skillfully put them in difficult circumstances. At first glance it could be thought that it’s just hardship and difficulty that is implicit in these kinds of challenges; but when you look a little closer, it looks more like what is happening in through these experiences is that the view is being clarified.

What is being clarified, or purified? How is it really purified? These questions are both rhetorical and actual and beg to be asked. Blindly following through a ngondro pecha may be better than killing insects, but perhaps only in that it plants seeds that one day one may actually practice ngondro. And when we actually practice ngondro, where is there anything that exists outside of that practice? Refuge is everywhere. The experience of Vajrasattva’s non-dual purity of unmodulated mind is everywhere. The accumulation of merit arises with every breath. The lama is everywhere. Yet when we don’t “practice” ngondro what happens to refuge, the essence of purity, the accumulation of merit, and the blessings of the lama and the lineage?

I feel that there is a lot of wisdom in being able to rest into the awareness that accompanies being. It acts as a reset button of sorts that allows us the ability to see things more clearly, to appreciate the richness of whatever arises without creating conflict, and to meet others where they are without needing to change them. In this way, and with this perspective as a motivational factor, the world around us has infinite potential as a ground for practice. New York Tsurphu Goshir Dharma Center becomes as meaningful as Bodh Gaya in India, Tsari in Tibet, and yet is no different from sitting on the subway of being surrounded by the overwhelming bustle of Times Square, as everywhere can be the center of the mandala of the experience of reality as it is. It’s impossible for everywhere and everything to no longer function as the ground for practice.

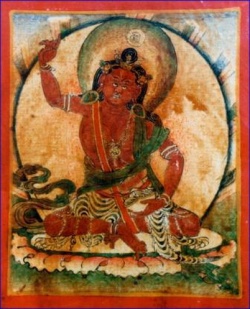

This is the wish-fulfilling jewel quality that can be associated with resting in being with all of the equivalencies that surround us. This is an expression of the multi-valent interconnected relationships that imbue our experience of reality with all of the qualities associated with pure appearance as described in dzogchen, mahamudra, the pure view or sacred outlook associated with yidam practice, and quite possibly the experience of grace in Christianity, or wadhat al-wujud, the unity-of-being as described by Sufi master Ibn ‘al Arabi.

So whether you are helping to renovate a place of dhrama practice, or simply liking it on Facebook, or enduring trials similar to those of Naropa, Marpa and Milarepa, or laying in a hospice bed in Queens, New York, who is to draw distinction between the type of, or depth of experience that we undergo?

Can we quiet our mind of endless comparisons? Or allow for the mind of analytic distinctions to settle itself?

In doing so, perhaps the simplicity of being that arises reveals a constant soft rain of blessings and opportunities for authentic clear being. May all beings taste this ambrosial nectar expressed by the blissful knowing glance of all of the mahasiddhas of all traditions in all world systems. Gewo!