Philosophy of Liberation according to Buddhism

General Introduction to Buddhist Schools

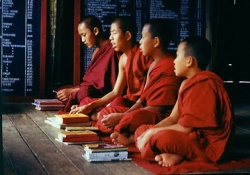

All the teachings that the Lord Buddha preached in the world are meant to be methods to lead sentient beings to ultimate state of liberation in accordance with their dispositions and individual level of mental aptitude. His scriptures were collected and came to be known as Tripitaka or Three Baskets, viz. the Vinayaka Pitaka (Basket of Ethics), Sutra Pitaka (Basket of Discourses) and Abhidharma Pitaka (Basket of knowledge). The Vinayaka Pitaka teaches and deals with the training of ethics, the Sutra Pitaka with the training of meditation and Abhidharma Pitaka with the training of transcendental wisdom. This shows that, whichever school of thought you follow, the process of practice remains the same as clarified by Acharya Vasubandhu in his Abhidharmakosa as follows: "Endowed with hearing and contemplation which are based upon moral conduct, one should thoroughly apply to oneself to meditation."

One should first have a good foundation of moral conduct, then engage in the study and contemplation of the scriptures, put them into practice through meditation and finally gain transcendental wisdom.

In accordance with the inferior and superior levels of mentality among the disciples, the above scriptures are classified under the Hinayana (Lesser Vehicle) and Mahayana (greater Vehicle0 teachings. Based mainly on the Hinayana and Vinayana scriptures, the first four divisions of Buddhism arose in the forms of Sarastivada, Mahasanghika, Sthaviravada and Sammitiya. Later, the two Hinayana schools of Vaibhashika (great exposition school) and Sautantrika (sutra school) were formed mainly on the basis of philosophical viewpoint. In the present time the Buddhist schools in Tibet and China, for instance, follow the Vinaya system of Sarvastivada, whereas their counterparts in Sri Lanka, Thailand andBurma follow the Vinaya system of Sthaviravada, which is called Theravada in Pali language. The most striking difference between the two systems is that under the Sarvastivada system a person wishing to become a novice or full monk must take the vow for entire life without any exception, but in the Theravada system one can become a monk for a limited period of time, eg. Six months, one year, etc.

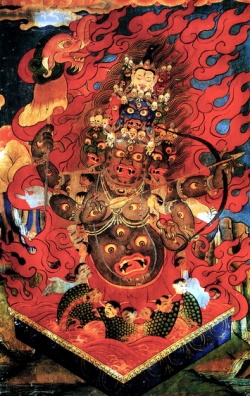

The Mahayana scriptures were further divided into that of Sutrayana or Paramitaya (Exoteric Buddhism) and Mantrayana or Vajrayana (Esoteric Buddhism). Based on the Paramityana scriptures the two Mahayana schools of Yogachara (Mind Only) and Madhyamika (Middle Way) were founded. While the whole of Tibetan Buddhist schools adhere to the Madhyamika system, some of the schools in Chinese and Japanese Buddhism follow the Yogachara system. The Vajrayana scripture is sub-divided into the four Tantras of kriya (Action), Carya (Performance), Yoga (Meditation) and Auttarayoga (Highest Meditation). Currently, one may perhaps find among the Tibetan Buddhists persons who advocate and practice Vajrayana most openly and vigorously even though Buddhism in Japan and Nepal have their share of Tantra too. The Kalachakra ceremony for world peace, which His Holiness the Dalai Lama conducts quite often in different parts of the world, is known example of Tibetan Buddhism's intense involvement with Tantra.

Meaning and Purpose of Liberation

All sentient beings equally desire happiness and do not want suffering, which is so not only for us intelligent humans, but also for the other creatures, even down to the tiniest worms and insects. Therefore, we must engage in the means which give rise to happiness and do not bring about suffering. Whatever we may do, there is no more perfect and complete means of achieving happiness and eliminating suffering than practising the Dharma, i.e. the Buddha's teaching. Relying on the Dharma we will be able to find means to generate happiness and eliminate suffering in this life as well as in future lifetimes. If the importance of Dharma is not understood and the benefits of teachings are not integrated with the mind, when there is a strong feeling of sickness in the body the mind cannot bear it. Great suffering will oppress both the mind and the body. If the importance of Dharma is understood, when the body experiences sickness, by seeing it as the result of previously accumulated wrongdoings, as being of the nature of cyclic existence and through wishing to take responsibility for the action by accepting the sickness, mental suffering will not be experienced. Consequently, external physical pain may be overcome by the inner power of mind, through which suffering will be dispelled. By putting faith in the law of cause and result and engaging only in virtuous deeds one may be able to take rebirth in the higher realms of existence and enjoy the comfort and happiness of Samsara. This can be considered as lowest level of liberation, having been liberated temporarily from the grave sufferings of the lower realms of existence.

Even though one will find means in the practice of Dharma to achieve happiness in this and other lives, one will come to realise that this happiness is not long lasting, irreversible and ultimate. As long as one is bound by delusions and karma in the cyclic existence, even though one is presently born in a happy state, one never knows when one is going to fall down in the lower realms to be oppressed by further suffering. One will also come to know that as long as one has attachment to the world of existence even though one may practice Dharma it will not lead one to the path of actual liberation. It is at this juncture that one will realise how one must become non-attached to the world of existence and generate the thought of renunciation to proceed on the way to liberation. When one attains this state of liberation one is freed from the chain of birth and death. However, it is still not considered as the highest and ultimate state of liberation because it is motivated by self interest and not supported by the accomplishment of skilful methods, such as loving kindness and compassion towards all living beings.

When one does not have attachment to one's own purpose and generates the minds enlightenment wishing to attain the state of Buddhahood for the sake of all sentient being; one has entered the path of Bodhisattava. A Bodhisattava is a practitioner who engaged in the practice of Dharma solely for the purpose of liberating all living beings from the suffering of Samsara. Such a Bodhisattava will realise that the only effective way to help all beings is for oneself to become a Buddha and attain the state of Omniscience. This is considered as the final state of liberation, since one becomes liberated from all kinds of obscuration and transcends the faults of both Samsara and Nirvana. The mere state of liberation from Samsara is called the one-sided Nirvana whereas the state of Buddhahood is referred to as the Non-abiding Nirvana. Those who abide in the one -sided Nirvana are known as Shravaka Arahat (Hearer Foe Destroyer) and Pratyekabuddha Arahat (Solitary Realiser Foe Destroyer) and those remaining in the Non- Abiding Nirvana are called Buddhas or fully-Enlightened ones. The practitioners, who do not have the capability of altruism and cannot join the Mahayana path to work for the welfare of all living beings, enter the Hinayana path and by accomplishing the practice set forth in it become a Shravaka or a pratyekabuddha. Others, who have the natural tendency to develop loving kindness and compassion to help all beings, prefer the Mahayana path and by engaging in the practice of Bodhisattva, finally become a Buddha.

Summary of Different Methods of Liberation

All the Buddhist schools based on a philosophical viewpoint are unanimous in negating the true existence of a self. They also agree that one must realise the emptiness of self in order to attain any level of Nirvana. Therefore, the main differences lie in negating the true existence of outer and inner phenomena and establishing and identification of Shunyata or emptiness. The two Hinayana schools of Vibhashika and Sautrantika base their philosophy on the so called Five Fundamentals, viz., 1) The fundamental of form-which includes the visible form, sound, smell, taste and tangible objects

2) The fundamental of mind - which consists of six consciousness, such as eye consciousness etc.

3) The fundamental of secondary mind or mental factor - which includes fifty-one types of mental factors, such as feeling, perception, desire, etc.

4) The fundamental of non-associated compositional factor-such as birth, ageing, impermanence etc. and

5) The fundamental of permanence - such as space, etc.

The Vaibhashika School believes that all these five fundamentals exist truly and substantially. What is to be negated, besides the self, are the coarse phenomena, which are, imputed by the conceptual mind, e.g. chair, table, etc. In addition to these negations the Sautrantika School negates the true existence of the last two fundamentals also. In brief, both the schools equally establish the inherent existence of a partless atom as an object of grasping and a momentless mind as a grasper. All other phenomena, including the self and other coarse objects, are merely imputed by the mind and so do not exist inherently. Therefore, a practitioner must strive to realise the selflessness of a person and the emptiness of the imputed objects, leaving aside other phenomena as truly existence. Depending on the motivation and skilful Methods to enhance this understanding of the true nature of phenomena some practitioners may attain the state of Arhatship and some may achieve the goal of Buddhahood. As far as the duration of practice is concerned, it takes at least three lifetimes for someone to reach the stage of Shravaka, one hundred aeons to attain the state of Pratyekabuddha and three countless aeons to become a Budhha.

The Yogacara School negates the true existence of all kinds of external phenomena, coarse as well as subtle. Since there isn't any object to be grasped, the mind of grasping also ceases to exist truly. So duality of the grasped and grasping is rejected. All the appearances of the grasped and grasping are delusive and they occur as a result of ripening of the Karmic imprints left in the mind from previous lifetimes. It is only the non-dual mind which they accept as the only truly existence entity. It is called the Alayavijnana (Universal Consciousness or Fundamental consciousness). Other than this consciousness all other phenomena must be rallied as empty of any inherent existence. This knowledge, supported by the methodical practices of six paramitas and so on, will lead one to the different states of liberation.

According to Madhyamika School, the three former schools are all substantialists since they accept the true existence of one or another entity. These schools assert that all phenomena, external or internal, self or otherwise, are devoid of any inherent existence. The theory of emptiness pervades all that appears to exist. Hence the emptiness is divided that of self and phenomena. The emptiness of phenomena is further divided into that of grasped object and grasping mind. By realising the emptiness of self, one will attain the state of Shravaka and by realising the emptiness of the grasped object in addition to former; one will attain the state of Pratyekabuddha. When one realises both the emptiness of self and phenomena one becomes a fully enlightened one. The period of time required for these practices is similar to what has been presented by the former schools. In Vajrayana school the theory of emptiness covering all phenomena is exactly the same as found in the Madhyamika Philosophy, but the differences are great when it comes to the application of methods. All the non-Vajrayana schools put emphasis on the training of the mind, which is sought as the focus of all the practices. Consequently, it takes a very long time for the practitioner to transform the deluded mind into pure transcendental wisdom. However, the practitioner of Vajrayana relies upon the manipulation of the physical body by dealing directly with the energy channel, wind and drops. With the help of these practices done under the proper guidance of an efficient master, it may even be possible for one to attain the blissful state of Vajradhara, i.e., the ultimate state of liberation, in this very lifetime.

System of Liberation According to Nagarjuna

Two Truths as Foundation

Since all the Tibetan Buddhists claim to follow the path of liberation expounded by Acharya Nagarjuna, an Indian master who was born four hundred years after the Mahaparinirvana of the Buddha, I will attempt to present in little more detail his views on the methods of achieving liberation. According to him, one must always remain within the aspect of middle way, whether it is in the beginning, middle or culmination of a practice. In the beginning, the foundation of Madhyamika is the unification of two truths. Before proceeding further on the path one must gain a proper understanding of the two truths, viz. The conventional truth and the ultimate truth. This is important because all teachings of the Buddha are based on these two truths one will be at loss to discern which teachings were given in the context of the conventional truth and which were taught in the purview of ultimate truth, which teachings can be considered as interpretative and which teachings as definitive.

That which is the object of a false mind is a conventional truth. This proves that whatever appears to the worldly mind is true only to that mind and so it is only conventional and not ultimate. In this case, what appears to be true to the beholder is not so in the real sense, because the object in question does not exist by its own and the mind of the beholder is tainted with delusions. By this reasoning all types of worldly mind are considered as false and whatever appears to them is not real. Within the conventional truth there are two types, the perfect and imperfect one. Whatever appears to the perfect sense organs, such as form to the eye and sound to the ear, is ascertained as perfect conventional truth, whereas the objects of the imperfect sense organs, such as yellowSnow Mountain to the infected eye, are classified as imperfect conventional truths. This distinction is necessary, because, when one engages in the accumulation of merits by performing virtuous deeds, one must take into account only the perfect conventional truth. All the practices of the method aspect, such as, taking refuge, developing enlightenment, thought and compassion and practising the six perfections, are based on this perfect conventional truth.

The ultimate truth is the object of a perfect knowledge. For the sake of explanation it is divided into two kinds, the nominal ultimate truth and the actual ultimate truth. That which is the object of analysing mind is nominal truth. In fact this is the mental image of the ultimate truth, which is projected, in the conceptual mind of the meditator. It is through image of the ultimate truth that one is trained in the study and meditation of the ultimate truth. The actual ultimate truth is said to be beyond thought and expression. It is the actual mode of being of every phenomena. It is the state of being free from all conceptualisations. In order to establish and generate conviction in the ultimate nature of all phenomena, one must apply various reasoning, such as the reasoning of negating production and that of interdependent origination. It the case of the first reasoning it is applied as follows. This appearance is not inherently existent because it is neither produced by itself, nor by others, nor by both, nor by neither. From the worldly point of view it is asserted that a sprout is produced from a seed. But when we analyse it from the ultimate point of view, we will come to know that the sprout has never been produced. When it is not produced in the first place we can easily understand that it does not disintegrate in the end. In other words, it is empty of any inherent existence and this emptiness is its actual mode of being. The same reasoning can be applied to prove the emptiness of all phenomena. In brief, a practitioner must understand the characteristics of the two truths to serve as the foundation of one's practice.

Compassion and Wisdom as Main Path

All living beings are equal in the sense that everyone cherishes oneself and wishes to gain happiness and to avoid suffering. However, within oneself one creates a variety of exaggerated reasons and makes discriminations such as "we" and "you", "my side" and "your side" and "enemy", "friend" and "neutral". One picks out those who are one's parents or relatives and whose race, nationality, language and ideologies are same as one's own. One considers them as on one's side and feels close to them. Those who are in disagreement with one's side are considered as on the other's side and one holds distant and reserved feeling against them. Thus, by separating living beings into different groups, such as enemy and friend or attractive and unattractive one engages in various physical, oral and mental acts motivated by attachment and hatred. In brief, as long as one regards the animate and inanimate phenomena as a basis of attachment and hatred and engages in acts of body, speech and mind under the influence of self-cherishing, it is impossible that the continuity of Samsara comes to an end.

Therefore, if one forsakes one's body, wealth, etc. for the happiness of others and puts oneself in the service of others, then both oneself and others will gain all the excellent happiness. On the other hand, if one commits harmful actions towards other's body, wealth, etc., for one's own sake and puts others forcibly into one's own service, then one will have to experience the sufferings, such as of being born as a serf, in future lifetimes. To be precise, all the happiness in the world has come into existence because of wishing happiness for others and working for others, motivated by the conception of cherishing others. All the sufferings have arisen from wishing happiness only for oneself as motivated by self-cherishing. Since the attitude of self-cherishing is the source of all the faults and is erroneous, one should abandon it. The conception of cherishing others should be understood as the source of all the Excellence and happiness. Therefore, those who wish to gain ultimate happiness should get accustomed to the conception of cherishing others more than oneself. To develop this attitude, the great compassion should be generated. For the generation of the great compassion, one must develop loving kindness towards all beings.

Loving-kindness is to wish happiness and causes of happiness for all beings, and compassion is the wish that all beings may be freed from suffering and causes of suffering. One of the methods to develop loving kindness and compassion is to visualise all beings as one's mother. For this, one has to realise all beings as one's mother, remember their kindness and think of repaying their kindness. In order to generate a true sense of love and compassion, one should train oneself in the practice of equanimity without being partial and attached to one's near one and hateful one to one's enemies. Another method of generating loving kindness and compassion is to contemplate the demerits of self-cherishing and the benefits of cherishing others. For this one should practice the equanimity of oneself with others and exchanging of oneself with others.

Since no phenomenon arises without cause, this Samsara too has its cause and conditions. Action and delusion are in fact the fundamental causes of Samsara. The self-grasping, which exists as inseparable from one's mind, causes the development of delusions which, in turn, motivate the good and bad actions and thus one revolves in the wheel of birth and death. Among the delusions in the self-grasping and self-cherishing are the principal causes of Samsara. The self-grasping functions as the root to all other delusions. The self-cherishing assists the self-grasping and leads one to generating attachment and hatred under the influence of which one commits all types of action, virtuous as well as non-virtuous.

Generally, the self, on which we use this designation, is an inter-dependant origination, which exists by depending on the basis of designation, i.e., the aggregates, and the designating factor, i.e., the term and thought. However, the innate self-grasping sees and grasps the self not just as imputed on the aggregates, but as naturally and ultimately existent one. This self, as grasped by the innate self-grasping, is to be negated and refuted. One should examine and come to the conclusion that there never is a self which exists by its own nature as held by the conception of the self-grasping. The self is neither same as nor separate from, the aggregates and so there does not exist a naturally formed self. In this way one must realise the selflessness. The same reasoning should be applied to all phenomena, to establish them without self - nature. When one realises the selflessness of all phenomena, one has gained the knowledge of perceiving the ultimate truth. This is the wisdom aspect of the practice. When one engages in the simultaneous practice of method and wisdom, it becomes the unification of both.

Attainment of Buddhahood as Final Liberation

One must familiarise oneself with the realisation of selflessness. This realisation should be supported with the practice of four limitless meditations and six perfections (paramita). Through these means of practice when one becomes free from the self-grasping one is said to have attained Nirvana and is called Arhat.

In order to abandon the entire obscurations of delusions and of knowledge, the Bodhisattvas realise and meditate on the selflessness through countless reasoning. They also study and practice all the sciences so that they can help sentient beings in accordance with their tastes. For instance, they make others develop faith in the true teachings. By studying the science of Medicine they can provide others with physical comfort and the happiness of being free from diseases. In addition, they train themselves in the six perfections for many aeons. These training's are reinforce with the practice of taking pleasure in doing anything and sacrificing everything for the welfare of other sentient beings through the motivation of even -mindedness and cherishing others more than oneself. By engaging in these trainings and practices for successive aeons, the Budhisattva finally attain the state of Buddhahood. After the enlightenment, a Buddha, from his own side, is capable of fulfilling the wishes of all beings, and through countless means and methods he leads countless disciples temporarily to the human and God realms and finally to the states of Nirvana and Omniscience.