Rinchen Terdzö (5)

At dinner tonight, Alexandra Kalinine described a bit of sunset chaos that erupted in the monastery courtyard in the late afternoon. A cow had found its way past the outer gate, through the courtyard, and made it as far as the steps up to the main shrine room doors. A number of young monks tried to chase it out, but the cow proved a worthy adversary, dodging the boys and some monastery dogs quite successfully. Alexandra spotted the cow from the terrace near the door to the second floor public bathroom. She was contemplating going down the steps when she saw the cow below trying to come up. Today we received all the empowerments of the last two Logos, Worldly Offerings and Praises, which was transmitted to Padmasambhava by Rambuguhya, and Wrathful Mantras, which was transmitted by Shantigarbha. There were about ten empowerments in the last two Logos. They were all brief. These two Logos are only performed by practitioners who have attained accomplishment in one of first five Logos, the transcendent group of practices.

The aim of Buddhist practice is to attain realization first and foremost, so it makes sense that the transcendent practices are the focus of the Eight Logos. The last two are rarely done. For the second day in a row we closed a little early, before seven in the evening. Usually we ended seven-thirty and sometimes after eight. It made me a little sad when we stopped the empowerments while there was still sun outside. Even after five hours of empowerments in a row, if we stop early there’s a slight feeling of loss when His Eminence leaves. I had the strangest thought yesterday, I could do this again. I shared this with someone else who said she felt the same way: “When’s the next Rinchen Terdzö?”

Jinpa, Shambhala’s monastic at the Rinchen Terdzö, has risen further up the ladder in the maroon and yellow world at the monastery. A few weeks ago he played the gyaling at the side of the room as the rinpoches and lamas made their way through the crowd with the empowerment articles in the evening at the conclusion of the empowerments. Today at one o’clock, he played the gyaling as part of the trio of monks who led His Eminence to and from the shrine room. Only ordained monastics can perform this function and they get to wear the dignified yellow hat. Jinpa and the rest of today’s procession was top notch.

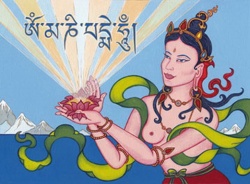

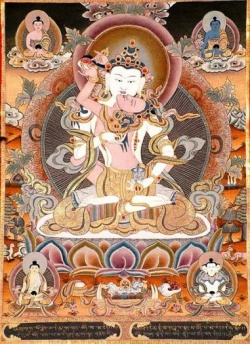

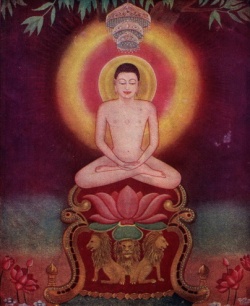

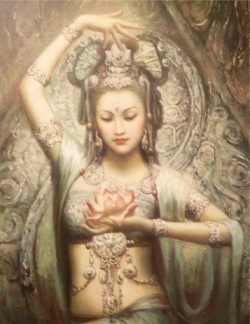

The conclusion of the Eight Logos empowerments yesterday meant that we had finished a major section of the Rinchen Terdzö, the yidam practices. His Eminence immediately started the empowerments of the next section, called the dakini, the root of activity. The dakini empowerments began with three abhishekas of Vajrayogini, the most famous type of dakini practice. Dakinis are feminine deities. The word dakini can also refer to a woman who manifests enlightened or worldly feminine energy in a powerful or extraordinary way. In tantric literature, it is explained that women are the embodiment of prajna, transcendent knowledge, and that men are the embodiment of upaya, the skillful means of benefitting others. Several years ago I was on pilgrimage with friends in Tibet, hiking the hills of Samye Chimpu, near Samye, Tibet’s first monastery.

The brush-covered, winding ridges of Samye Chimpu are pocketed with retreat caves where a great number of termas have been discovered. For example, Jigme Lingpa’s famous cycle of termas, the Longchen Nyingtik, was discovered at Samye Chimpu in a cave that is one of the blackest places I have ever ‘seen’ (when the butter lamps are out). There were many miraculous things to discover at Samye Chimpu, such as Padmasambhava’s head-print in rock, and the self-arisen stone dais that manifested beneath King Trisong Detsen’s daughter Pemasal when Padmasambhava brought her back to life in order to teach her the Pema Nyingtik before she went on to her next birth. When we walked down one of the ridges at Samye Chimpu at the end of the afternoon, I thought I spied another cave entrance hidden in the brush. Our interpreter Dorje, a Tibetan from Amdo who’d been with us for a month and with whom we’d become quite close, heard me wondering aloud what lay beyond the path through the bushes. In his early twenties, Dorje was discovering his Buddhist roots and was eager to help us connect in whatever way he could to the dharma. Without warning, he scrambled through the brush to toward the cave and began calling out a greeting before anyone could protest that he might disturb a retreatant.

A moment later he emerged from the brush saying that it was a nice cave and he’d met a yogini that we should come meet. A yogini is a female tantric practitioner; a yogi is a male tantric practitioner. Sometimes these terms are used loosely in the West, but the basic meaning is honorific. A yogini or a yogi is someone who is genuinely practicing yoga, union with the ultimate nature of reality. In classical texts the words refer to people who are realized. The essence of the yogini principle is embodied in the sadhanas of Vajrayogini, the indestructible yogini. Getting back to the story… When we entered the cave we were introduced to an extraordinarily peaceful and kind nun with a shaven head and a simple shrine beside her. We were a bit shocked to learn that she’d been in retreat there for eleven years. After finding out that it was ok we’d just popped in, a bit of conversation ensued and she offered us tea while we talked. For me, the quality around this yogini was that nothing extra was happening. She was plainly who she was and there was no detectable neurosis around that.

I have experienced this with other people who’ve spent long periods in retreat. It’s like they aren’t experiencing discursive thoughts; there’s no echo of mental speed in what they say or how they act. The space around people like this feels somehow cleaner and saner than what’s generally accepted as normal. I don’t know how it came up, but at some point she told us that three different rinpoches had said she was a real dakini and asked her to marry them. With each one she said no, and told them she preferred to remain in retreat. At that point I asked her to tell us what it meant to be a dakini. She replied that it meant your mind was inseparable from Guru Rinpoche, Padmasambhava. We stopped the empowerments today part-way through a series of ten related Vajrayogini abhishekas found in the rediscovered termas of Jomo Menmo, a 13th century yogini who was an emanation of Yeshe Tsogyal, Padmasambhava’s Tibetan consort.

Jomo Menmo’s presence in the Rinchen Terdzö was inspiring; female tertöns are rare. Vajrayogini herself gave Jomo Menmo the terma called The Gathering Of All The Secrets Of The Dakinis when Jomo Menmo was twelve years old. Jomo Menmo, then a sheepherder, had been awakened from a nap she was taking near the entrance to one of Padmasambhava’s caves of attainment, a place where practice could be very strong. Inside the cave, a secret door opened and she joined a feast with Vajrayogini and many other dakinis. Jomo Menmo was told to practice The Gathering Of All The Secrets Of The Dakinis, but to keep it secret. Jomo Menmo was an amazing practitioner with wonderful qualities, but the majority of people where she lived believed she’d been possessed by a mountain spirit, so she took to wandering the country with no fixed destination. This style of practice was not uncommon in Tibet. Later she met Guru Chökyi Wangchuk who understood that she was Yeshe Tsogyal. For a short while she and he were consorts. Guru Chökyi Wangchuk advised her that it was not the time to reveal The Gathering Of All The Secrets Of The Dakinis, so Jomo Menmo continued to wander Tibet accompanied by two accomplished female practitioners.

Then, when she was 35, having secretly benefitted many beings, she and her two companions performed a feast on a mountaintop in central Tibet, flew off into the sky like birds, and entered Padmasambhava’s pure realm without relinquishing their bodies. Jamyang Khyentse Wangpo rediscovered Jomo Menmo’s terma in the 19th century. Jamyang Khyentse Wangpo had been Guru Chökyi Wangchuk at the time of Jomo Menmo. The Jomo Menmo empowerments were among the most elaborate and complex we received during the Rinchen Terdzö. As they were bestowed, a large group of dark skinned Indian women appeared at the door near the side of the stage. Their saris were bright solid colors: red, white, blue, yellow, green, and so on. They looked extremely shy. There were tiny girls and tall women, and they stood clustered together in a group. At first none of them even dared to step over the threshold into the shrine room.

They seemed awed by His Eminence, and most all of them had their palms pressed together at their hearts. He looked over to the group and gave them several beaming smiles as he continued the empowerments. The dakini empowerments continued today with the conclusion of Jomo Menmo’s Vajrayogini abhishekas and an empowerment of a Vajrayogini yangter from Rigdzin Gökyi Demtruchen. Vajrayogini is ‘the anthropomorphic form of shunyata,’ as Chögyam Trungpa Rinpoche once put it. She is how emptiness might look if one were to actually meet it. As a deity, she is visualized as a dancing, wrathful goddess surrounded by the flames of wisdom. She holds a knife that cuts conceptuality in one hand and a skull cup filled with the amrita in the other. Vajrayogini practice is special to the Shambhala community because it was the sadhana that Chögyam Trungpa Rinpoche taught in the most depth. Many of the students of the Mandarava, Padmasambhava’s Indian consort Vidyadhara have practiced Vajrayogini intensively at some point. It was poignant to witness such a wide variety of Vajrayogini abhishekas. It continued to be eye opening to see that there were so many ways to present the each of the practices in the collection.

Following the Vajrayogini empowerments we received two empowerments for practices of Tara, Drölma in Tibetan. Tara is sometimes translated as, ‘She Who Liberates’. Tara is sometimes described as compassion embodied in a human form. One of her principal expressions of compassion is to liberate beings from fear. The great Indian teacher Nagarjuna wrote a praise to the twenty-one forms of Tara. Most, if not all, of the lineages of Tibetan Buddhism have a wide range of Tara practices. Sakyong Mipham Rinpoche has written a short Tara practice and there is at least one short Tara supplication in the collected Tibetan works of Chögyam Trungpa Rinpoche. Tara’s story is relevant to all of us. Khenpo Tsültrim Gyamtso Rinpoche explains that kalpas ago Tara was born as a virtuous and gifted being with great faith in the dharma and the Buddha of that era. At that time she was a princess named Yeshe Dawa, Moon of Wisdom. She had an enormous ability to practice the dharma and through this had a glimpse of supreme bodhicitta, the heart of enlightenment. At that time, all the ordained monks around urged her to pray that she to be born as a man through the power of her merit so that she could accomplish great benefit for the teachings.

The story continues:

This seemed a mistaken understanding to Princess Yeshe Dawa. So, she replied: “Here, there are no men, there are no women, There is no self, no individual, and no perception. These labels of ‘male’ and ‘female’ are meaningless, They are the utter confusion of weak-minded worldly beings.” Thus she taught the equality of all things. “Many are those who wish to attain enlightenment with a male body, But no one wishes to do so with a female body. Therefore, with a female form, till samsara is emptied, I will vastly accomplish the benefit of beings.” Thus she vowed.9 And so Tara has continued to benefit beings to this day in a female form. Tara’s two most popular practices are White Tara and Green Tara. White Tara is known for conferring vitality, healing, and also fertility. In a monastery near Swayambunath Stupa in Kathmandu there is a 9 Khenpo Tsültrim Gyamtso Rinpoche composed these two verses in 1997. They are part of his text, The Origin Of Tara In Brief, translation by Chryssoula Zerbini, copyright 2010, Marpa Foundation.

White Tara statue that has actually spoken on occasion. The statue wears many jeweled necklaces that were given to her by women who’d been unable to conceive until they came and made prayers before her. There is a speaking Tara at the Mahabodhi Stupa in Bodhgaya too. Green Tara is associated with protection and activity. People often practice Green Tara when travelling. The 16th Karmapa practiced Tara when taking off and landing in airplanes. As for what Tara protects us from, there are lists of 21, 16, and 8 kinds of fears. The eight fears to be protected from are the fears due to lions, wild elephants, fire, snakes, thieves, imprisonment, floods, and demons.

Some of these fears are more rare in the modern world than they were in ancient India. However, Orissa is still a place where cobras, tigers, and elephants roam wild, and Shambhala Mountain Center is sometimes host to rattlesnakes, mountain lions, and bears. These eight fears are sometimes connected with eight negative states of mind: pride, delusion, anger, jealousy, wrong views, avarice, desire, and doubt. Tara’s vow is that she will manifest to those who sincerely request her help during times of great distress.

Shambhala and Padma Ling students again joined together for Padmasambhava feast in the old monastery this evening. Yesterday there was a minor controversy about when the actual feast day was. Several Westerners were adamant it was on the 4th of February. However, the chöpöns at the monastery, who very kindly make extra tormas for us on feast days, were firm in their position that today was the day and therefore would not make us a torma on the 4th. So, we did the feast on the 10th lunar day, as it was perceived in Orissa. The lunar calendar is used to reflect the interrelationship between the flow of energies in the body and the movement of outer energies like the sun and the moon. The Westerns students decided to do a single feast with one of His Eminence Namkha Drimed Rinpoche’s termas of Padmasambhava rather trying to do two simultaneous feast practices the way we did last month. This suited our international group well because we could sing the liturgy together in Tibetan.

At one point, we came to what is known in Shambhala as the Jigme Lingpa Feast Offering. This we did three times in Tibetan and then three times in our own languages, all at once—French, Spanish, German, and English. Feast again included arak, the locally brewed hard alcohol, which some of us mixed with orange soda. After the practice, a few well-behaved dogs that sleep in the trees next to the old monastery gobbled up the leftovers. Earlier in the day I met with the Sakyong. He had been very busy writing during the breaks in the empowerments and this was the first meeting with him in several weeks. The

Sakyong was relaxed and happy. He remarked that this event was somewhat historic in that it may have been the first time a Western audience has really been let in at the Rinchen Terdzö. He pointed out that in the early years, Westerners would never be allowed to ask the chöpöns questions. To be able to walk into the chöpön’s room and ask how to read the abhisheka outlines, and be able to check over what happened at the end of each day, has been a real blessing. Our own three-year retreatant, Kristine McCutcheon, has made some of the tormas used in the abhishekas, which is another sign of our ability to meet the tradition. Today we continued with the dakini empowerments. These alternated between different forms of Vajrayogini and Tara. We also received the Taksham terma practice of Yeshe Tsogyal. This empowerment was lengthy and, of course, a special moment for the monastery. Tomorrow we will we start with Dechen Gyalmo, the famous dakini practice from the Longchen Nyingtik, which was bestowed by His Holiness Dilgo Khyentse Rinpoche at Karmê Chöling, in Boulder, and in Halifax in 1987.

[This letter was sent from the Sakyong Wangmo, Dechen Choying Sangmo to the Shambhala Community during the Rinchen Terdzö.]

Dear Subjects of Shambhala, ! Even though I am far away from many of you, you are in my heart. I am constantly thinking of you all and wondering how you are doing. !My husband, the Sakyong, jokes that this is the marathon of abhishekas, and having entered the dakini section, in the third month of the Rinchen Terdzö Empowerment, completing about five hundred abhishekas, I am beginning to agree with him. !

The days are passed essentially in group retreat, much like the dathüns in Shambhala. Every day is basically the same, and every evening, with a large gathering of lamas, monastics, and lay people, we all do aspiration prayers dedicated to all sentient beings. ! Here in Orissa, we have both the monastic community of monks and nuns, and the lay people attending from the five main Tibetan refugee camps as well as from all over India and the Himalayan region. There are also many adventurous students from Shambhala and Ripa (students of my brother, Jigme Rinpoche, from Europe and the U.S.) It is amazing to see these different cultures gathering together under one mandala, devotedly receiving the abhishekas.

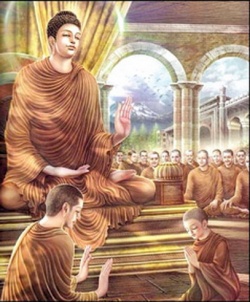

This reminds me of what the Buddha said, about how the dharma would gather together all races and all cultures. !I am very moved by how my father, His Eminence, Tertön Namkha Drimed Rinpoche, is taking such care in passing the lineage on to the Sakyong. And I am delighted that there have been fundraising parties and gatherings to support this. For those of you who could not be here, this is a wonderful way to contribute and participate from afar in the Rinchen Terdzö empowerments. I hope that in the future, many of you will be able to come and visit the monastery and see the surrounding community. !I cannot express how meaningful the Rinchen Terdzö is for our community.

Many local people see His Eminence putting so much time and effort into this, and they have told me—especially some of the older ones who escaped from Tibet—how fortunate they feel that such a major teaching is taking place. The community members often thank me, saying how grateful they are that the Sakyong requested and is sponsoring this historic event. Everyone is benefiting tremendously whether near or far, and to think, all this is happening because of our marriage! How amazing! Ki Ki So So! ! Yours in the vision of the Great Eastern Sun, ! The Sakyong Wangmo, Dechen Choying Sangmo !

Jamgön Kongtrül Lodrö Thaye didn’t create the Rinchen Terdzö alone. His main inspiration and guide was his guru, Jamyang Khyentse Wangpo (1820-1892). In an interview last week, Jigme Rinpoche stressed how crucial Jamyang Khyentse was in the development of the collection. He said: Jamgön Kongtrül’s source of authenticity and approval for the termas was Jamyang Khyentse, Pema Ösel Do Ngag Lingpa (Jamyang Khyentse’s tertön name.] He was also Jamgön Kongtrül’s teacher. For Jamgön Kongtrül, the only person who could definitely authenticate was Khyentse. Jamgön Kongtrül did more work on the Rinchen Terdzö, but the actual source was Khyentse.

This is because so many of the termas teachings included in the Terdzö were almost extinct, and some were actually extinct. Somehow, Do Ngak Lingpa, Khyentse, brought these back to life through his visions of the earlier tertöns. Jamyang Khyentse Wangpo was born in Derge, eastern Tibet. He was an exceptional rebirth who even as a child had a strong motivation to help others and a desire to become a monastic. In his youth he could recall his previous lives. The presence of the protectors Mahakala and Ekajati seemed to accompany him and, on some occasions, they were actually visible to people with him. He was like many other tertöns described in this blog, a brilliant scholar who was a voracious learner.

From an early age, Jamyang Khyentse Wangpo had many visions of teachers and deities. His termas, based on his clear recollections of previous lives, and his pure visions are voluminous. We received empowerments related to his discoveries at least every other day during the Rinchen Terdzö. One reason for the large number of his discoveries was that when he was forty, after being supplicated repeatedly by Jamgön Kongtrül for help in recovering the ancient termas, Jamyang Khyentse Wangpo was blessed in an extraordinary way by Padmasambhava during a pure vision. As a result, Jamyang Khyentse Wangpo was able to see all the tertöns and terma teachings from the past, from his time, and from the future that would arise in Tibet. Even with all these accomplishments and the ability to see all tertöns and termas, Jamyang Khyentse Wangpo still continued to study impartially with teachers from all lineages, 150 different teachers in total. This led him to study or receive the transmissions of over 700 volumes of teachings. This kind of manifestation is inconceivable from the standpoint of ordinary academic ambition. It absolutely does not make sense that someone of such realization would so diligently continue on the path of study.

The only way to understand what Jamyang Khyentse Wangpo did is to see it from the point of view of helping others by gathering, preserving, and spreading the teachings. Khyentse Wangpo said that he’d made no more progress on the realization of mind’s nature after receiving a particularly profound set of teachings at the age of nineteen. This might sound like he is being humble somehow, but it actually shows that he was already completely realized at the start of his brilliant and magnificent life. This is how he accomplished so much. Besides preserving the dharma through teaching, explanations, and practice, Jamyang Khyentse built many libraries, constructed and restored numerous monasteries, and he commissioned a large number of statues as well as many woodblock and handwritten editions of scriptures. Printing was very important in 19th century Tibet, a place with relatively poor means and still using woodcuts for printing texts.

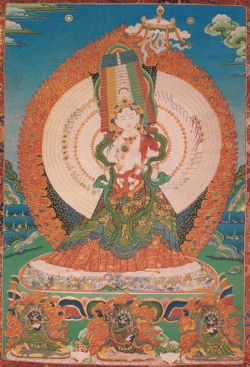

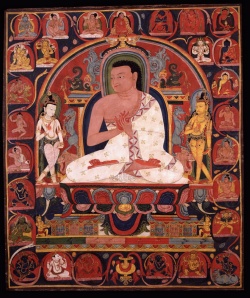

Although miracles are not the point, it’s both poetic and inspiring that the rice Jamyang Khyentse threw in offering to the principal statue of the Buddha in all Tibet, the Jowo in Lhasa, spontaneously turned into white flowers. Rice tossed in offering is a substitute for flowers. At the age of 72 Jamyang Khyentse Wangpo passed away. At the time of his passing there were gentle earthquakes and his face was said to be as radiant as that of the moon. His body became as light as cotton. This sign is in an indication of the attainment of rainbow body, the exhaustion of the coarse and subtle defilements and fixations in a great meditator. Cynthia writes: In this painting, Jamgön Kongtrül turns to his right and bows his head towards the flaming jewels in front of his seat. With this simple direct gesture, he is exemplifying to us the honor to be given to the Buddha, his teachings, and the community of practitioners, and to the consequent realized masters over time, the personal yidams, the dakinis and dakas, and all the protectors of their mandalas. Kongtrül holds his hands in the dharmachakra mudra at his heart level. It is the gesture of turning the wheel of dharma thus activating the teachings in our world system.

Two lotus flowers are seats for the purity and liberating capacity of Kongtrül’s enlightened qualities, which are symbolized by the flaming sword rising above the Perfection Of Wisdom10 text on his right, and the auspicious vase topped by a symbol of tendrel chingwa, the interdependent relationship that is the nature of all phenomena. This symbol—derived from the Sanskrit root sv-asti, meaning well-being and good fortune—also indicates prosperity. Turning in a clockwise direction, the reverse swastika symbol is considered the seal of the Buddha’s heart, expressing the powerful illuminating radiance that the Enlightened One extends to all, like the rays of the golden sun.

The fullness yet emptiness of the gold vase to his left indicates Lodrö Thaye’s embodiment as the union of wisdom and compassion. The sun and moon circles in the sky represent the red and white bindus fully mature. This is another visual sign of the inseparability of absolute and relative bodhicitta, which is the vital heart essence of Jamgön Kongtrül Lodrö Thaye’s manifestation. I painted this image many years ago, while Kyabje Kalu Rinpoche was living in this world. The composition wasn’t complete with landscape and a few other details until recently. When Kalu Rinpoche saw the image, he blessed it by writing in his own hand the seed syllables for the three chakras on the back of the work. He mentioned some of the enlightened qualities of the Great Lodrö Thaye as kind and gently refined with great humility. In our lifetime, His Eminence Kyabje Jamgön Kongtrül Rinpoche is considered the mind emanation of Kongtrül Lodrö Thaye, Dzigar Kongtrül Rinpoche is considered the speech emanation, and Kyabje Kalu Rinpoche is recognized as the activity emanation.

Maggie Smith arrived with Allya and Paul Burke today. Their jeep pulled into the small parking lot in front of the guesthouse at teatime. At that moment, most of the lay people attending the empowerments had also arrived in the parking lot. They were on their way home because the rest of the day’s empowerments were restricted. The dusty white four-byfour carrying the new guests had to creep through a crowd of a few hundred Tibetans who were on foot or revving motorcycles in front of the guesthouse. A cow relieved herself in front of the jeep as it finally rolled to a stop. Asked later if the crowd had slowed their arrival, Maggie cheerfully replied, “No more than anything else on the way here.” Today we completed the dakini section of the Rinchen Terdzö, the section devoted to the feminine deities that are the root of enlightened activity. We finished with a flourish of 10 Prajnaparamit practices for Tara, Vajravarahi, Guhyajnana (Secret Wisdom, a deity mentioned in Jamgön Mipham’s Great Clouds Of Blessing), Mandarava, and Yeshe Tsogyal. The very last empowerment in this section was for a chöd practice in the Mindroling tradition. Chöd practice is interesting.

Generally speaking, the main part of the chöd practice begins with the ejection of consciousness. One visualizes that one’s consciousness leaves one’s body of flesh and blood through the crown of the head, and one arises in a form of Vajrayogini, the embodiment of wisdom. Then one imagines offering one’s ordinary body, blessed as divine food, to all enlightened beings, all suffering beings, those with whom one has karmic debts, and all spirits and demonic forces who want to do harm to others. This kind of visualization develops insight into emptiness along with strength of compassion, and it helps one to relate more sanely to fear and death. Sometimes advanced practitioners deliberately practice chöd in frightening places like charnel grounds where corpses are cremated or fed to vultures. The Asian belief is that ghosts lurk in charnel grounds, so practice in such places gives one greater opportunities to work directly with fear and confusion. Ultimately, all appearances in life and death are manifestations of the mind. The idea of a ghost or demon vanishes with the genuine realization of this insight.

For the best practitioners, chöd practice in a charnel ground can be a fast track to that realization. The word chöd means to severe or cut. One cuts one’s idea of there being a self. Selflessness is an unfamiliar concept in the greater Western world. We aren’t used to entertaining the idea that beneath our day-to-day thoughts and activities, the underlying assumption of a ‘me’ being there is an unnecessary addition. However, it’s not that absolutely nothing is happening, that there’s absolutely nothing and nobody there. Selflessness means that our assumption of a ‘me’ (or for that matter, something outside called an ‘it’) as an unchanging, permanent thing separated from everything else in the world is a form of confusion. The teaching of selflessness points out that what we think of as the ‘me’ is not there. Even though the ‘me’ can’t be found, we function anyway. We don’t need to rely on the idea of ‘me’ in order to function in life.

The cause of our suffering turns out to be thoughts and actions attached to the idea of a ‘me’ as being something real we have to defend. If this understanding is brought to bear both on the ‘me’ as well as on the rest of our experience, insight and the capacity to help others will blaze like a bonfire. Chöd practice became popular because of Machig Labdrön (1031-1129), the most famous female practitioner in Tibet after Yeshe Tsogyal. Her name means Only Mother, Lamp of Dharma. It is said that when she was a baby, a third eye visibly emanated from her forehead. This was not like a normal eye, but a sign of divinity, and people had great faith in her. Machig Labdrön was very, very intelligent. One sign of this was that she had an incredible ability to read. A good reader can read one volume of Tibetan text aloud in a day. An exceptional reader can read aloud three volumes in a day. Machig Labdrön was able to read twelve volumes in a day. They say she could see the back and front of several pages at once. When she spent a month reciting the twelve-volume, 100,000 verse Prajnaparamita Sutra thirty times in succession she gained complete enlightenment.

The Prajnaparamita sutras are the most thorough presentation of selflessness spoken by the Buddha in the mahayana tradition. Machig’s achievement was unique in Tibetan history because it is difficult to attain complete realization in one life through recitation of Prajnaparamita, a mahayana method, as opposed to relying on the vajrayana methods of visualization, mantra recitations, inner yogas, and so on. Mahayana methods are said to be gradual and can take many lifetimes to perfect; vajrayana methods are explained to be much faster. Machig later combined her realization of Prajnaparamita with the chöd practice that she’d received from the Indian siddha Padampa Sangye. Her teaching became so popular that it was even brought to India. It was the only practice from the Tibetan tradition that was certified as valid by the Indian panditas, the most learned practitioner-scholars of that era. Following our afternoon tea break, His Eminence began the empowerments of the protector section of the Rinchen Terdzö. Protectors are the embodiment of the environment of awareness that surrounds and protects the dharma. Chögyam Trungpa Rinpoche gave his students a practice called kasung to train people in embodying the protector principle.

Ka means command or teachings, and sung means to protect. Kasung is one of the Tibetan words for protector. What protects the dharma, what protects goodness and sanity, is awareness, not weapons or aggression. For example, during a formal teaching, a few people doing kasung practice will sit on the perimeter of the shrine room while maintaining awareness of the overall situation as opposed to taking notes or exclusively listening. One of the mottos of the kasung is, “Victory Over War.” The focus of kasungship is creating and protecting an environment of warmth and decency. The protector principle, besides being a practice, is also an experience. While usually gentle, sometimes the experience of protector principle can be sharp. One of the most direct experiences I’ve had of this occurred in 1987 while I loaded food cartons into Karmê Chöling’s basement during the visit of His Holiness Dilgo Khyentse Rinpoche.

I was distracted and making up a loud, senseless rhyme as I stood receiving boxes part way down a storm door stairwell into the basement. I was near enough to Khyentse Rinpoche’s window to be heard by His Holiness or anyone is his room, but I was oblivious of that. Suddenly one of the steel storm doors became unbalanced and slammed straight down on the top of my head. I was not hurt, but my energy was cut completely. It felt like being slapped awake. While the door falling on my head was pure coincidence, the message was clear, ‘Watch your mind.’ Protector practice makes us more sensitive and available to making that kind of connection. Such sensitivity is particularly important on the contemplative path. One wants to avoid the sidetracks of aggression, self-absorption, grasping, and other neuroses because they can upset stabilization of compassion and insight.

Working with protector principle guards one’s development and sustains the general environment of the teachings. There are many different types of protectors just as there are many different gurus and yidams. Different termas have different protectors, as do different lineages, teachers, places, and types of teachings. There are many stories of realized teachers actually meeting the protectors and yidams as if in person. These kinds of stories are beyond our everyday experience and are provocative to think about. My personal feeling about this is that if someone completely realizes and embodies the teachings, the energy around them becomes quite intense. Chögyam Trungpa Rinpoche’s poem titled, Meetings With Remarkable People, gives some insight into an enlightened being’s experience of the deities. The poem begins a vivid description of meeting with three protectors and concludes with: I witnessed these extraordinary three friends in the flesh. Surprisingly, they all spoke English. They had no problem communicating in the midst of American surroundings.

What do you say about this whole thing? Don’t you think meeting with such sweet friends is worthwhile and rewarding? Moreover, they promise me that they will protect me all along. Don’t you think they are sweet? And I believe them, that they can protect me. I would say meeting them is meeting with remarkable men and women: Let us believe that such things do exist. p. 125 The word ‘protector’ is a short way of saying dharma protectors, or chökyong in Tibetan. They carry out the four enlightened actions of pacifying, enriching, magnetizing, and destroying. They can be divided according to whether they are a wisdom, action, and worldly protector. Wisdom protectors or dharmapalas can be male or female and are known as ‘great black ones’, or mahakala and mahakali in Sanskrit. These are fully enlightened beings sometimes indivisible from a deity like Avalokiteshvara. Action protectors carry out the wishes of the wisdom protectors and are part of their retinue. Worldly protectors (Skt. lokapala) are not fully enlightened, but have taken an oath to protect the teachings and practitioners.

The protector section of the Rinchen Terdzö is divided into a section for the mahakalas THE GREAT RIVER OF BLESSINGS 172 and action protectors, and a second section for various other protectors, principally the female wisdom protectors. The second section includes, for example, mahakali like Ekajati and lokapalas like Magyal Pomra. A short section related to Bön deities and protectors follows the protector section of the Rinchen Terdzö. ;4C,/'%E,/%;+F),-)% =)@.C#.N%X$"% This morning it was still dark when I started work on the blog. Outside, there was a steady soprano chorus of crickets chirping. In the distance an overtaxed radio blared Hindi music at the other end of camp four. Occasionally, the sound of a ritual bell made its way over from the monastery to the bathroom window where I quietly typed as Patricia slept.

On the rare mornings when I got up around four o’clock, I heard the gyalings accompanying His Eminence from his bedroom in the monastery to the shrine room for his morning practice. With the coming of dawn around six o’clock, the ravens started their array of calls from the mango trees in our neighbor’s yard. Some people thought they were mina birds because their calls were so varied, like little children playing with sounds for fun. Then, small twittering birds that looked like finches added a high background chorus to the backyard symphony that accompanied the coming daylight. About this time, the human sounds started. First, a day helper at the neighbor’s house shouted to wake someone to inside to unlock the door. Then, a calling gong rang from the monastery, and at around 6:20 the first bus from the other camps in the Tibetan settlement bugled and grinded its way towards the monastery gates. In the guesthouse, one or two alarm clocks beeped and were swiftly silenced. At 6:30, the voice of the umdze leading morning chants was broadcast from the loudspeakers perched on the monastery roof, and afterwards the sounds of the reading transmission filled the valley with Lhunpo Rinpoche’s powerful staccato.

The lung soon became the main aria for the morning, surrounded by the occasional themes of motorcycle engines, barking dogs, and mooing cows. This all continued until around 8:00, when the first part of the day eased into breakfast in the monks’ dining room, the canteen, the guesthouse, and the various houses around the village. The protector empowerments turned out to have a different atmosphere than the empowerments for the guru, yidam, and dakini. All the protector empowerments were restricted to monastics and people who’d completed ngöndro and could keep the commitment of either daily protector practice or attending a feast that included a protector sadhana at least once a month. Along with the monastics, the group remaining in the shrine room included fifteen or twenty Tibetan and Bhutanese tantrikas (non-monastic vajrayana practitioners, all wore robes), a handful of lay people, and most, if not all, of the Westerners who’ve completed ngöndro.

Since the size of the assembly had reduced itself by half, the doors to the huge shrine room could be shut instead of being left open to the veranda. The environment was considerably more quiet and grounded. Over the last two days we moved quickly through the list of protector empowerments. Some of the abhishekas were skipped because we had already received them during the guru or yidam section. This was the result of the 15th Karmapa’s ordering of the Rinchen Terdzö. Many protector empowerments were quite short, which also sped up our pace. Today we also learned that the official conclusion of the Rinchen Terdzö was now set for just after the start of the New Year. At that time His Eminence would formally enthrone the Sakyong and Lhunpo Rinpoche as holders of the Rinchen Terdzö lineage. I thought it would be interesting to list some of the protectors we were introduced yesterday and today because many are already practiced in Shambhala. The first was Ganapati, who is mentioned in The Invocation for Raising Windhorse. Ganapati is an emanation of Avalokiteshvara.

We also received the rest of the five Ekajati empowerments in the Rinchen Terdzö. Ekajati is one of the main protectors of the Nyingma teachings, and is practiced at several different centers in Shambhala. Ekajati practice began at Karmê Chöling because Chögyam Trungpa Rinpoche said that eventually the dzogchen teachings would be given there. Next we received empowerments for Achi Chökyi Drölma (practiced during the Söpa Chöling three-year retreat), and for Dorje Yudrönma, the protector associated with the Vidyadhara’s mirror divination practice. Many of the protectors were guardians of specific terma cycles. Some of the protectors were connected to the kama, the oral lineage of the Nyingma that has come down uninterruptedly from the time of Padmasambhava.

Many of us enjoyed watching a particularly little monk. He was among the youngest monks living at Rigön Thupten Mindroling. Watching him prostrate was entertaining and sweet because it was a bit of a battle between him and his robes. He and another monk about his age often hid near the shrine room door to get a close look at His Eminence’s arrival in the afternoon.xtremely young children come to a monastery it is sometimes due to family misfortune. I remember a very young monk at Benchen Monastery in Kathmandu several years ago. He would wait near the shrine room door at the end of the teachings every day so that he could be sure to have a place beside Tenga Rinpoche at afternoon tea. He was so small that even standing he was barely taller than an adult sitting on the floor. Both of this monk’s parents had died suddenly in a car crash. At two years of age he had been placed in the care of Tenga Rinpoche and the monastery. However, the little monk in Orissa had a different story.

The Sakyong Wangmo told us that his name was Dorje and that his parents were allowed to give him to the monastery at an extremely young age because even as a baby he displayed many habitual tendencies towards practice. The Sakyong Wangmo added that several of the older monks who have remained at the monastery after finishing their education have a similar story. I am pleased to present the first in a two-part post from Acharya Fenya Heupers. Fenya was following the blog and sent a compilation of her notes from a seminar given by the Vidyadhara Chögyam Trungpa Rinpoche in 1974. The seminar focused on three different Jamgön Kongtrüls. The first, Jamgön Kongtrül Lodrö Thaye (also known as Jamgön Kongtrül the Great), lived in the 19th century and compiled the Rinchen Terdzö. He was a guru to many great teachers, including Chögyam Trungpa Rinpoche’s prior incarnation, the 10th Trungpa, Chökyi Nyinche. After Jamgön Kongtrül passed away he had two simultaneous rebirths. Having multiple rebirths is not uncommon for great teachers. Both of these rebirths counted the 10th Trungpa among their gurus. The first rebirth of Jamgön Kongtrül Lodrö Thaye was Jamgön Kongtrül of Shechen, meaning Shechen Monastery.

He was one of Chögyam Trungpa Rinpoche’s root gurus and he bestowed the Rinchen Terdzö upon Chögyam Trungpa Rinpoche. The second rebirth of Jamgön Kongtrül was Jamgön Kongtrül of Palpung (Palpung Monastery) who gave Chögyam Trungpa Rinpoche his monastic vows. Although Acharya Heuper’s notes and quotations are not the exact words of Chögyam Trungpa Rinpoche, they have the raw feeling of his teachings. The quotations in the notes are Stories of the Kongtrüls from the Vidyadhara Chögyam Trungpa Rinpoche By Acharya Fenya Heupers On the joyous occasion of transmission of the Rinchen Terdzö, when Sakyong Mipham Rinpoche becomes the lineage holder of this tradition of his father, the Vidyadhara Chögyam Trungpa Rinpoche, through the tremendous kindness of his father-in-law, His Eminence Namkha Drimed Rinpoche, I remembered teachings of the Vidyadhara on Jamgön Kongtrül.

In November and December 1974, Chögyam Trungpa Rinpoche gave a seminar in Boulder on Jamgön Kongtrül Lodrö Thaye. He taught about his root guru Jamgön Kongtrül of Shechen and what it means to study with an authentic teacher. He also talked about Jamgön Kongtrül Lodrö Thaye, who collected endangered teachings and empowerments in various collections, the Rinchen Terdzö being one of these collections. Jamgön Kongtrül Lodrö Thaye was part of a renaissance of Tibetan Buddhism in the 19th century, known as the Rime, or nonsectarian, movement because this group of teachers did not want to fixate on sectarian differences between the various schools. In those days the Vidyadhara used the word ‘ecumenical’ for Rime, a word that Westerners were familiar with from the Christian tradition. The Vidyadhara explained the difference: “Rime is not as naive as the 20th century ‘ecumenism’. That ecumenism says: we are brothers and sisters, why do we fight? There is good intention in that, but the reality is that we, as human beings, are all brothers and sisters, and that’s why we fight.

There is no reason for fighting if there is no communication. The biggest problem is trying to unify the cosmos and to structure it so that everybody eats jellyfish and everybody drinks milk. If we give up hope of unifying the world, and accept chaos as it is, there is a possibility, then there might be peace. It is uncertain whether harmony is the answer to develop peace. Jamgön Kongtrül accepted chaos as well as orderliness. He was able to find profundity within complication.” Chögyam Trungpa Rinpoche also explained how sectarianism came into existence: “The teachings originate from experience, and are expressed in words, then the words are recorded and become doctrines. Logic is needed to prove the validity of these doctrines and then there is a battlefield and clashes between the doctrines because they cannot understand each other’s language. Finally there is complete confusion; intoxicated in their own doctrine, they cannot see the other doctrines.” The Rime movement brought back the contemplative tradition, which is a complete approach to buddhadharma, including both learning and practice, understanding and intuition. Sitting without learning is like wandering blindly; learning without sitting practice is like trying to climb a rock with crippled arms.

The understanding of buddhadharma is experiential; it is not rejecting scholarship, but including it. That demands dedication and devotion. Without those we are working only on the surface. So Jamgön Kongtrül had two approaches: to conquer the ocean of learning and to conquer the space of practice. In order to do so, one has to commit oneself 200%. Not that you do not eat or sleep, but they are included in that commitment. Bringing learning and practice together is not difficult. It is like stepping on dog shit; you know what you’ve done, you smell it, experience it, so there is a complete experience of intellect and intuition at the same time. Jamgön Kongtrül of Shechen used to ask, “How do you feel about it?” instead of asking about facts and figures. The contemplative tradition is personal living experience. So he seemed to be more pleased with Trungpa Rinpoche’s critical attitude than with acceptance. Jamgön Kongtrül the Great first trained himself thoroughly in the Kagyü tradition; he was a fully ordained monk. He had to live very humbly, had to beg. He learned basic solid Buddhism, about mind and emotions according to the hinayana, about bodhisattvas in the mahayana, and about the play of phenomena of tantra.

Jamgön Kongtrül established himself in Palpung, at Jewel Rock, home of devis and dakinis. He studied texts very arduously to the light of a butter lamp or just the red glow of an incense stick. He practiced meditation with stinging nettles around his meditation box. If he fell over to sleep he woke up by the stinging. He was very austere, but loved metaphysical jokes. He was a great punster. After a solid training in one tradition, he studied under 100 masters of various schools. After him these schools faded out. In this way he revived the contemplative tradition. He worked together with the tertön Chogyur Lingpa, with Patrül Rinpoche from the Nyingma tradition, and with Khyentse Rinpoche from the Sakya tradition. He brought together teachings from the eight Buddhist traditions in Tibet, and brought them into the contemplative tradition.

The 10th Trungpa was a student of Jamgön Kongtrül the Great. Frustrated by spiritual materialism he suddenly decided to escape from his monastery and studied with Jamgön Kongtrül the Great. Then he returned to his monastery (Surmang) and realized that it was not so evil, that he did not have to become a mendicant monk. He was planning to visit his guru again; then he heard that his guru had died. He continued his life of practicing meditation.”

This is the second and final installment of the post from Acharya Fenya Heupers, Stories Of The Kongtrüls From Chögyam Trungpa Rinpoche. We pick up with Chögyam Trungpa Rinpoche’s description of the two rebirths of Jamgön Kongtrül Lodrö Thaye. Jamgön Kongtrül had two incarnations: Jamgön Kongtrül of Palpung and Jamgön Kongtrül of Shechen. Jamgön Kongtrül of Palpung was a son of the 15th Karmapa. The 15th Karmapa was a student of Jamgön Kongtrül the Great, and had decided to follow his discipline and tradition in the Kagyü order as a married man. This created an uproar. One Kagyü khenpo teacher had wept for seven days when he learned that the Karmapa had married and taken off the monastic robes. The Karmapa proclaimed that his marriage was in keeping with the Kagyü tradition.

Then the Khenpo had a vision of the 15th Karmapa in Vajradhara costume with a black hat.11 The 15th Karmapa’s son turned out to be the first incarnation of Jamgön Kongtrül. Jamgön Kongtrül of Palpung also found everyone very materialistic and felt that the monastic people wanted to use him to get gifts from benefactors and disciples of Jamgön Kongtrül the Great. So he also decided to escape as the 10th Trungpa had done earlier. He went to the 10th Trungpa and demanded ordination. The 10th Trungpa hesitated because he did not want to make enemies with Palpung, but finally he gave him ordination and Jamgön Kongtrül became his student. The other incarnation, Jamgön Kongtrül of Shechen, wanted to be a student of the 10th Trungpa as well as another Rinpoche from Shechen.

He had hardships and he camped around monk’s houses until the abbot of Shechen monastery created headquarters for him with a tutor and attendant. As a teenager Jamgön Kongtrül of Shechen was very stern and he did not talk very much. Once he warmed up he was very verbal. He was extraordinarily dedicated to learning. The Vidyadhara heard 11 The black hat is a symbol of the Karmapa’s lineage. from an older disciple of the 10th Trungpa that when he visited the room of Jamgön Kongtrül of Shechen there were books all over the place. He was sleeping on them, there were pages all over, but he could find the right page. He had extremely bad eyesight from straining too much to read. His guru sent him up to a cave to meditate for several years at a time. The Vidyadhara Chögyam Trungpa Rinpoche was ordained by Jamgön Kongtrül of Palpung, and received meditation instruction from Jamgön Kongtrül of Shechen. In working with Shechen Kongtrül, Trungpa Rinpoche “felt paranoid because you cannot fool him with being well-behaved. His main approach is how you carry yourself as a sane person. He could have outbursts with sticks and fists on students to break their stubbornness and aggression.

When you work with someone who is not really in the teachings, everything can be very smooth. But if you work with someone who is really connected with the teachings, then you find yourself in contact with reality, with more sharp edges and you become 100% more sensitive. “Jamgön Kongtrül and I had a small but neat world, so much power in the whole cosmos to conquer. They were the good old days. Don’t give up hope in the bad new days, which will become then good old days. We appreciate Kennedy because he was killed; Martin Luther King was a great man. If you’d meet Naropa or Tilopa on the spot you’d be pissed off. History is very deceptive, reality is more important. There is a piece of philosophy for you.” “When you meet your guru, your spiritual friend, there is uncertainty.

It is like the nature of a mirror, a reflection between you and guru that is so intense that you think you make the whole thing up. The function of a guru is on different levels: acting very compassionate as an enlightened nanny; as a very efficient accommodating garbage bin; very learned wise in philosophy and wisdom. There is an atmosphere where things are percolating and established.” Trungpa Rinpoche was nine years old when he first met Jamgön Kongtrül of Shechen. The day before his head was shaved again with a blunt razor and sulphur instead of soap, an excruciating experience. After this ordeal there was a sense of relief and expectation. At the welcome ceremony Jamgön Kongtrül seemed a kind old monk, nothing extraordinary. He was spontaneous and somewhat sloppy. Trungpa Rinpoche was accused by his tutors of being sloppy, so he expected that they correct Jamgön Kongtrül’s sloppiness as well.

When everything is valid, well trained, well disciplined there is room for craziness. Jamgön Kongtrül’s eyesight was very bad, but sometimes he would spot people from miles away. He did not behave according to what a guru should look like. He embarrassed people, he was spontaneous not impulsive. I (Trungpa Rinpoche) felt for the first time: ‘My hang-ups are okay.’ There was some human quality and all his attendants were very gentle and sane. Chögyam Trungpa Rinpoche recounted learning about meditation from Shechen Kongtrül at Surmang Monastery’s retreat center. In retreat in Dorje Khyung Dzong there was the first meditation instruction. I (Trungpa Rinpoche) expected an extraordinary experience. There were beams of sunlight and he would talk about mind. [This next section is from Chögyam Trungpa Rinpoche’s perspective.] !“Do you have a mind?” Shechen Kongtrül asked. ! “I can think so many things, I must have a mind.” Trungpa Rinpoche replied. “That’s intelligent. Let’s sit together and do nothing.” Shechen Kongtrül responded. ! I expected something extraordinary. Nothing happened. He is pleased. I am confused. Why is he pleased with nothing that happened? At the second meeting nothing happened, but something happened. A feeling of the room very light, sun, old incense, sense perceptions. Then he instructed me in shamatha-vipashyana, that was a great help. Something happened, nothing happened.

Your breath makes something and nothing together. At the fourth meeting I was excited and asked, “What about enlightenment?” Lots of silence, which was slightly threatening. “There is no such thing as enlightenment, this is it.” Jamgön Kongtrül is so solid there is no question of labeling, just tuning into atmosphere. Later, the experience is that as soon as you are going to see Jamgön Kongtrül, there is a radiation. Things get more and more intense, a feeling of fear and uncertainty, also a feeling in the bottom of your heart that you are tickled. There is doubt and uncertainty for some time, is this sanity possible? It proves to be possible. Later the Vidyadhara Chögyam Trungpa Rinpoche studied with Jamgön Kongtrül Rinpoche in Shechen monastery for several years and was confirmed as a lineage holder. When Chögyam Trungpa wanted to meet him again, Jamgön Kongtrül had been arrested by Chinese troops and put into prison. He died there. The Vidyadhara escaped and came to the West. [This all comes from notes of this seminar of Fenja Heupers. Any errors in this are mine. (Fenja) I hope it will inspire someone to transcribe the whole seminar and make it available.]

Before the closing chants last night, His Eminence Namkha Drimed Rinpoche gave a short dharma talk to the people attending the protector empowerments. His Eminence gave an explanation of the basic elements of liturgical practice with an emphasis on visualization and dissolving a visualization. It was clear to everyone that His Eminence was giving his heartfelt, direct advice to the younger monks about how to develop their practice and understanding. After breakfast this morning, the knowledgeable Russian translator, Nickolai Almerov gave the Westerners a synopsis of what he’d heard His Eminence teach. The key point in His Eminence’s remarks seemed to be that it easy to memorize the chants and do the rituals, but if that is not joined with real contemplation of the meaning or doing the practice from the inside, then there is not much benefit. At the end of empowerments yesterday, it was announced that today was a break for everybody. It was good to catch our breath before the concluding month of abhishekas and the coming New Year. A lot of laundry got done while people attended to various projects. In the afternoon, several of us walked to the tiny restaurant-shack built on the shore of the little lake ten minutes walk from the monastery. It stood under some shady trees just down the embankment of the road to the camp. The dirt road on the embankment had rows of vertically hanging prayer flags, more like dozens of fluttering banners, forming a colored wall on either side. The prayer flags were strung from steel frames.

The frames were Jigme Rinpoche’s inspiration. He saw that cutting down trees to put up flags was a bad idea in our era. The metal frames were constructed with tie-holes put in at six-inch intervals along the top and bottom edges. The bottom edge was constructed about two feet up from the ground. People then could use the frames to hang lots of six-foot prayer banners and the effect was that hundreds of white, red, yellow, blue, and green bands of fabric fluttered in the wind on either side of the road. The walls of color were soothing to look at and delightful to walk between. Prayer flags have mantras written on them so that the wind can carry the prayers out into the world. There were some tables set up in the shade outside the lakeshore restaurant, and a couple more tables were set up inside the slightly dilapidated hut. The energetic Tibetan woman who ran the little restaurant was cheerful and kind. She sometimes went about her work with a slumbering infant tied on her back with a red and white shawl. About seven or eight of us spent the late afternoon eating deep-fried chicken and potatoes pies while sipping India’s famous Kingfisher beer under the trees.

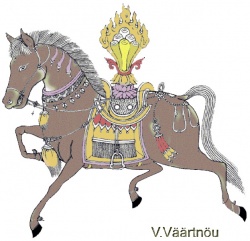

We concluded the section of the Rinchen Terdzö devoted to the protector empowerments today, ending with an abhisheka for a Magyal Pomra practice discovered by Rigdzin Mingyur Dorje. Magyal Pomra is a lokapala, a worldly rather than transcendent protector, who is associated with Machen Pomra, a high mountain and its connecting range in the Golok region of Tibet. One can see this mountain in the distance from a high pass on the way to Surmang monastery from Xining. Gesar of Ling, the enlightened warrior-king of Tibet was born and raised near Machen Pomra. Magyal Pomra protected and sustained him as a child, sometimes even bringing him chang to drink. Magyal Pomra is one of the most powerful nyen or mountain deities in the Tibetan Himalayas. The nyen existed in Tibet before the arrival of Padmasambhava. Magyal Pomra and many other indigenous deities took oaths before Padmasambhava and other greatly realized teachers to protect the Buddhist teachings. He is also one of the 13 dralas who vowed to protect the kings of Tibet. Nyen are more powerful than human beings and some are highly realized on the path. Magyal Pomra, for example, is seen as an 8th or 10th level bodhisattva.

In less technical language, his meditation is the same as a completely enlightened buddha’s, and his time off the cushion is so permeated with virtue and previous positive aspirations that he is moving rapidly and inexorably towards complete enlightenment. Because nyen are like the lords of their particular areas, offerings are made to them in order to keep harmony with the governing forces of the region. Magyal Pomra is described as an armored warrior on a white horse and holding the three jewels (of the Buddha, the teachings, and the sangha) in one hand while raising a whip in the other. Chögyam Trungpa Rinpoche once said, ‘Gentleness is the best whip.’ I strongly suspect that Magyal Pomra carries this kind of whip. Sometimes a white horse will be set free at the foot of Machen Pomra as an offering to Magyal Pomra. One account I read of such an offering said the horse ran straight up the mountain until it was completely out of sight. Through his relationship with Gesar of Ling, Magyal Pomra cares for those in Gesar’s bloodline, such as the Mukpo clan.

The Mukpo family lineage includes Sakyong Mipham Rinpoche and his father, Chögyam Trungpa Rinpoche. Magyal Pomra was chosen by the Vidyadhara to be the protector for two mountain retreat places, Shambhala Mountain Center and the wild and delightful southern Colorado retreat, Dorje Khyung Dzong. Magyal Pomra’s Tibetan home is in an area called the Blue Lake Province, which is known for its especially pure blue waters. Therefore, Chögyam Trungpa Rinpoche chose Magyal Pomra as a protector for the blue watered region of Nova Scotia, the center of the Shambhala community.12 After the protector empowerments concluded, we received empowerments for four related Bön practices, one of which was a combined supplication to a Bön deity named Bönse Wangdrak Barwa and Magyal Pomra, who is a figure both in the Bön and Buddhist traditions.

Jamgön Kongtrül Lodrö Thaye grew up in an area where many people practiced Bön. In his youth, he meditated at a nearby Bön center and knew the rituals and practices well. Because of his knowledge of Bön and the clarity of his vision, Jamgön Kongtrül chose to include Bön termas in the Rinchen Terdzö. There was some dispute with this decision during his life, but Jamgön Kongtrül proved that the termas were authentic and said they must be included in the collection. The Bön tradition is much smaller than the Tibetan Buddhist tradition. This was also true in Jamgön Kongtrül’s day. The religions endured an uneasy relationship during different periods of Tibetan history. Before the arrival of Padmasambhava, Bön was the main religion in Tibet and practiced by many people in King Trisong Detsen’s court. When Padmasambhava 12 The protector empowerments are introductions to specific deities in the context of specific terma practices.

The short protector chants done at the different Shambhala centers need no empowerment. arrived, he spoke with the Bön practitioners, learned their views, and conferred with the king. The Bön practices that brought good fortune and were powerful in strengthening one’s energy, healing the sick, prolonging life, and so forth were kept. However, King Trisong Detsen banned the Bön practices that were not in harmony with the dharma, such as animal sacrifice. I recently heard that some Nepalese shaman say they are the descendents of the Bön practitioners who were driven from Tibet at that time. King Trisong Detsen’s ban resulted in periods of serious conflict between the two traditions. The worst of it occurred two generations after King Trisong Detsen, when King Langdarma aggressively punished the Buddhist community and nearly destroyed the tradition of monastic ordination.

A monk named Palkyi Dorje, who was a previous birth of Chögyam Trungpa Rinpoche, later assassinated King Langdarma. Overall, Bön can be said to have three forms: a white Bön related to the life enhancing practices, a black Bön that employed more negative elements like animal sacrifice, and the Bön that is most prominent in our modern era. The latter form of Bön has an elaborate nine-stage progression of teachings remarkably similar to the Nyingma presentation of the nine yanas leading to dzogchen practice. Many contemporary Bön practices are identical to those presented in dzogchen although the lineage and deities are different from those presented in Buddhism. The lhasang, popular in the Tibetan tradition and in Shambhala, has its roots in Bön. It is characteristic of Jamgön Kongtrül Lodrö Thaye’s non-sectarian vision that Bön was presented in the context of the Rinchen Terdzö so that everyone’s mind could open toward all the spiritual wealth Tibet has to offer.

This afternoon, Sakyong Mipham Rinpoche received his usual list of the abhishekas scheduled for the day along with a tally of how many empowerments had passed, and how many we estimated might be ahead. Along with that, Patricia added the following estimates: Approximate number of times the Sakyong has stood up: 5,980 (10 times per empowerment times 598, the number of empowerments received so far by our count). Distance the Sakyong has travelled between his seat and His Eminence’s throne during the empowerments thus far: 6.8 miles (5980 times 1 yard each way).

Today we started an important new section of empowerments called the auxiliary sadhanas, more formally known as the auxiliary sadhanas of activity rituals. The auxiliary sadhanas are the second major section of the sadhana section empowerments in the mahayoga section of the Rinchen Terdzö. As you may recall, we started with the empowerments in the tantra section and then moved to the sadhana section, whose first division was the root sadhanas practices, which are the sadhanas for the guru, yidam, dakini, and protector. Many of the deities in the auxiliary sadhanas section are found in the root sadhanas section too, but in this case the practices are used in context of a ritual for a specific enlightened activity, such as the pacification of suffering, the enrichment of health, and so on. The auxiliary sadhanas were also the final block of empowerments in the sadhana section, and therefore the conclusion of the mahayoga empowerments altogether. In a sense, they also marked the beginning of the end because the two final sections of the Rinchen Terdzö, the abhishekas of the anuyoga and atiyoga, were very brief in comparison to the mahayoga section.

By this time, most of the Westerners who’d been in Orissa for more than a few weeks were talking about plane tickets along with sharing rumors of who might arrive for the final days of this extraordinary event. It was sad to think of the end, but it was nice to know that unlike a movie, which climaxes in the middle, the Rinchen Terdzö would climax during the final days of empowerments with the profound atiyoga section and the enthronement of the new lineage holders. This was somewhat like the path of awakening itself because realization is both the release of suffering and the time one can really appreciate the dharma and be of benefit to others. The auxiliary sadhanas section lasted several days, and had two main divisions: rituals or liturgical practices of a general nature and rituals for specific activities. All the practices presented in the auxiliary sadhanas section were still for practices used in specific contexts, however the practices of a general nature were somehow more generic, such as rituals for setting up a retreat.

The practices in the rituals for specific activities were for very specific contexts, such as pacifying an epidemic. The word ‘activities’ refers to virtuous or enlightened activities as opposed to actions without virtue, actions that are either meaningless or harmful. The first division, the rituals of a general nature, was short and completed during the early part of the afternoon. It contained, for example, in the subcategory of rituals for intensive retreat, two empowerments for the wrathful deity, Amritakundalin whose chief function is to remove obstacles. The rituals of a general nature also contained empowerments for the deity Agnideva, the deity related to the element of fire and practiced in the context of a fire offering. The four separate empowerments in this sub-section were related to the different enlightened activities that can be demonstrated by fire: pacification, enrichment, magnetization, and fire’s wrathful aspect of destruction. These empowerments came from termas revealed by Mingyur Dorje. Some rituals of a general nature didn’t need an empowerment.

These included practices like ceremonies for the benefit of the dead, and certain kinds of feast and torma offerings. After the rituals of a general nature, His Eminence began the empowerments for sadhanas related to specific activity rituals. This category had two parts: the supreme activity rituals, which were the activities focused on liberation, and the ordinary activity rituals, which were activities focused on creating harmonious conditions for the benefit of others and the continuance of the teachings. There were only three supreme activity empowerments, all of which had to do with ‘liberation through wearing.’ Liberation through wearing involves wearing a particular sort of intricate, mantra-filled diagram or text. Specific calligraphies or texts of this type are created so that someone can wear the item either throughout her or his life or at the time of death. Wearing something in this manner is done in order to achieve realization more easily. In many ways, it is an extended meditation on the meaning of something. Our awareness becomes much stronger at death and therefore, with the right conditions, it can be easier to key into the meaning behind a mantra diagram or another distillation of the teachings.

This has the function of helping liberate a practitioner, of helping her or him to realize buddha nature directly. An image of a mantra-diagram for liberation through wearing can be found in some editions of Chögyam Trungpa Rinpoche and Francesca Fremantle’s translation of The Tibetan Book Of The Dead, The Great Liberation Through Hearing in The Bardo. The second section of the specific ordinary activity rituals had a large number of subdivisions. One of the practices presented in this section was to bring blessings down on sacred places.

There were also empowerments for practices to reverse or to turn back obstacles related to the elemental factors of earth, water, wind, and so on. In this and the previous section, there were subsections that contained no empowerments, for example the section on prognostication. The specific ordinary activity rituals broke into five major sections: protection, pacification, enrichment, magnetizing, and wrathful action. Several of the ordinary activities sounded pretty flashy. However, vajrayana teachers say these kinds of practices are not to be hankered after. Fixation on worldly powers can turn into a potentially dangerous sidetrack. Besides creating obstacles for oneself, practice with a worldly motivation can have negative results for others. The practices of the ordinary activities are performed by realized meditators or practitioners who have been instructed to so by a realized teacher.

The ordinary activities, when performed with great compassion, are highly effective in clearing away obstacles and increasing positive circumstances for all beings. Generally speaking, it is best to focus first on the attainment of wisdom and love for all beings, and then build out from there. Dorje Lingpa, the third Kingly Tertön, was the third of the five tertöns who were direct reincarnations of King Trisong Detsen, the ruler who firmly planted the dharma in Tibet with the help of Padmasambhava during the 8th century. Dorje Lingpa was in 1346 in central Tibet, the region where the Tibet’s ancestral rulers lived and where the Tibetan dharma first flourished. At the age of seven Dorje Lingpa took monastic vows and studied the sutra and tantra teachings thoroughly. At the age of 13, after having seven visions of Padmasambhava, Dorje Lingpa found his first set of termas by following a terma inventory that had belonged to the second of the Kingly Tertöns, Guru Chökyi Wangchuk, who had passed away about 80 years earlier.

Dorje Lingpa discovered his first set of termas in the Tara shrine room at the Tradruk temple in central Tibet. This temple was one of the earliest Buddhist structures in Tibet and was built by the seventh century Tibetan king, Songtsen Gampo. Songtsen Gampo, Trisong Detsen, and Tri Ralpachen were the three ancestral kings who actively propagated Buddhism in Tibet. Presently, a Tara thangka that was embroidered in pearls by Songtsen Gampo’s Chinese wife, Princess Wengchen, hangs in the reconstructed upper shrine room at Tradruk temple. When Dorje Lingpa was 15, he went on retreat in one of Padmasambhava’s caves of attainment. During the retreat, Padmasambhava appeared to Dorje Lingpa, constructed a mandala, and gave Dorje Lingpa empowerment.

During that retreat, Dorje Lingpa also discovered a large number of terma cycles along with sacred substances, ritual objects, and four volumes of texts that had belonged to King Trisong Detsen. These events were just start of Dorje Lingpa’s activity. He was quite prolific, if that is the right word, and discovered 43 major terma troves and many other minor ones. There are about 20 different termas associated with him spread throughout the entirety of the Rinchen Terdzö, including one Bön terma. Dorje Lingpa discovered many Bön termas during his career, along with termas on medicine and astrology. Dorje Lingpa was one of the first tertöns to extract termas in public. In one of the most astonishing demonstrations of his miraculous power, Dorje Lingpa emanated two bodies, extracted termas from two places simultaneously, and left impressions of his feet that plunged about forearm’s length into solid rock. This occurred at the Chuwori mountain cave complex southwest of Lhasa. Padmasambhava, Yeshe Tsogyal, and Vairocana, the great early translator of whom Jamgön Kongtrül is an emanation, appeared to and taught Dorje Lingpa on several occasions. He also taught and gave empowerments to the many gods and demons of Tibet who came to visit him.

Dorje Lingpa passed away at the age of 65, but his corpse did not decay for three years. This phenomenon still occurs in our era. Today in Thailand, several realized practitioners’ bodies remain without decay at their monasteries. What is surprising in the case of Dorje Lingpa is that his body would sometimes speak, give teachings, and recite dedications of merit. After three years his body was finally cremated with many amazing signs. His family lineage still exists in southern Tibet, near Sikkim. Today we continued the empowerments for the auxiliary sadhanas related to various ordinary activities, the enlightened activities of awakened mind in this world. One series of empowerments was for a group of deities called the Four Kings. This empowerment was part of the section of empowerments related to the activity of protecting a region.

The Four Great Kings are usually described as worldly protectors who have vowed to protect the teachings. They are regularly supplicated to protect ‘sealed’ or closed retreats, and are painted outside the main temple doors of every Tibetan monastery. The Four Kings are also visible on the walls of the post-meditation hall outside the main shrine room of the Boulder Shambhala Center in Boulder. Iconographically, each of the Four Kings has a place in one of the four directions at base of Mount Meru, a mountain that sits in the center of the world according to one of the main Buddhist cosmologies. On and above this mountain are the abodes of progressively more powerful and sublime gods. The Four Kings have rulership over several different types of beings that are ordinarily imperceptible and can sometimes interfere with the lives of humans. Dhritarashtra, the Great King of the East Through making a positive relationship with the Four Kings one gains a more positive relationship with everybody in their domain. Sometimes the Four Kings are described as the lowest level of the desire realm gods. Below these gods are everyone else in the desire realm including people, animals, and a variety of beings usually not accepted as real by most scientists.

The Four Kings are ‘gods’ because they enjoy a more refined level of experience than we do, but they are part of the desire realm because they still desire objects of the five outer senses, such as beautiful forms, pleasing sounds, and so on. The higher the god in the desire realm, the more subtle the god’s relationship with the objects of the five senses. Above them, in the god realms of form and formlessness, the deities only have interest in mental objects of pleasure, such as experiences of pure joy or of limitless consciousness. It’s worth a brief digression here to say that rebirth as a god is not the liberation from suffering famous in Buddhist practice. What liberates us from suffering is a direct experience of the absence of a sufferer.

If we have confidence and stability in the recognition that there is actually no sufferer, we are able to deal with our obstacles in any realm more skillfully and we can be of real help to everybody else. At the same time, it is important to train the mind towards the level of mental stability prevalent in the more refined states of existence because a stable mind provides the support for contemplation and insight into profound topics like the absence of a sufferer. Other empowerments today included those for types of reversals, meaning turning back or averting obstacles, and empowerments for protection from obstacles in general, protection from illness, and so on.

I have been reflecting that the auxiliary sadhanas express the powers one would need in order to properly rule the world as an enlightened monarch. A Sakyong, as the ruler of Shambhala world and as an example of joining the vision and practicality, needs to be able to enact all kinds of enlightened actions for the benefit his or her kingdom. A general description of an enlightened ruler’s activities in the form of the four dignities is presented in Sakyong Mipham Rinpoche’s book, Ruling Your World, and in Chögyam Trungpa Rinpoche’s seminal text, Shambhala, The Sacred Path Of The Warrior.

The fastest Rinchen Terdzö we’ve heard of took a month and a half. It was given by the previous incarnation of Dudjom Rinpoche at Rewalsar, the little lake town that Tibetans call Tso Pema, in foothills of the Indian Himalayas. I think this amazing event might have occurred at Dudjom Rinpoche’s lakeside monastery, Orgyen Herukay Podrang. This monastery is home to a round stupa designed by Chögyam Trungpa Rinpoche. During that extremely fast Rinchen Terdzö, Dudjom Rinpoche bestowed both the empowerments and the reading transmissions. In fulfillment of a prophecy, it was the 10th and final time he bestowed the Rinchen Terdzö during his life. Dudjom Rinpoche is also the author of the exhaustive book, The History Of The Nyingma Lineage, which was a great help in writing the blog. The longest Rinchen Terdzös have lasted six months.

This was the case when the previous Kalu Rinpoche gave the Rinchen Terdzö at Sherab Ling, near Bir, India in 1984. The six-month figure is a bit misleading because the event included a one-month break for group practice. We fell somewhere in the middle of things and concluded all but the final empowerments just before Shambhala Day, Losar, which fell on the 25th of February, the next new moon. The Tibetan New Year traditionally takes three days or more to celebrate. It is also a time when everybody, including the teachers, is ‘at home,’ spending time with family. The start of the New Year is also a chance for friends to visit one another and for people to make a personal connection with their teachers at the start of a new cycle. This afternoon’s abhishekas began with some final empowerments from Chogyur Lingpa’s cycle of seven pacifying goddesses, a terma cycle we’d started yesterday. The pacifying section of the auxiliary sadhanas section was long and the atmosphere in the shrine room has been soft for the last few days. Often pacifying practices are associated with the color white. The practices introduced to us have been for deities like White Tara and the white longlife deity name Ushnishavijaya (also called Jaya Devi) whom I’ve seen in an old Tibetan thangka painted directly above the head of one of the Rigdens of Shambhala.