Sects at the time of the Buddha

The two main religious movements at the time of the Buddha were those of the brahmans and the samaṇas. The brahmans adhered to Brahmanism and considered the Vedas to be the ultimate spiritual authority. However, the more forward-looking brahmans of the day were starting to doubt the efficacy of Vedic rituals and to give more attention to ethics and meditation. In particular, they were increasingly uneasy about Vedic sacrifices, which involved the slaughter of animals. Some of these liberal brahmans founded schools, but saw themselves as still within Vedic orthodoxy.

The samaṇas on the other hand, rejected the Vedas and most Brahmanical beliefs and practices and were considered unorthodox, even heretical, by the brahmans. This brahman disapproval of samaṇas is well illustrated by Ambattha’s comment that the Buddha and his disciples were ‘petty, shaven menial samaṇas, the black scum of Brahma’s foot.’ (D.I,90). The last part of this insult refers to the belief that low caste people were created from the feet of Brahma, the supreme god. Because most samaṇas ignored caste rules, this put them on a par with low castes and outcastes in the eyes of the brahmans.

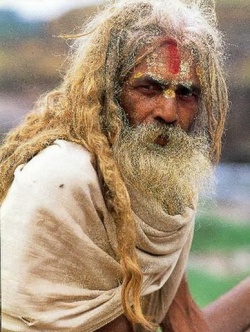

The samaṇas ignored social norms and expectations, they were usually celibate, and in spiritual matters they gave precedence to experience rather than scriptural authority. They experimented with meditation, self-mortification, yogic breathing, fasts and sensory deprivation. When, as a result of such practices, an individual had some kind of mystical experience which led him to believe he had attained enlightenment or liberation, he would attract disciples and this would lead to the founding of a new sect. Some of the sects mentioned in the Tipiṭaka include the Ajīvaka (Those of the Pure Life), the Muṇḍaka Sāvaka (the Shaven Disciples), the Jaṭila (the Matted-hair Ones), Paribbājaka (the Wanderers), the Māgaṇḍka, the Medaṇḍika (the Trident-bearers), the Aviruddhaka (the Free Ones), the Gotamaka (Gotama’s Followers), the Devadhammika (the Godly Ones), and the disciples of the mysterious Dārupāttika (He of the Wooden Bowl, A.III,276; D.I,157). These and other samaṇa sects were also collectively known as ‘ford-makers’ (titthiya) because they claimed to be able to show the way to ‘cross over’ from this world to the next. Later, Buddhists used this term for any non-Buddhist samaṇas. The two dominant samaṇa sects of the time, and the only ones to survive to the present, were the Nigaṇṭhas (the Bondless Ones, A.III,276), later known as the Jains, and the Sakyaputtas, i.e. the Buddhists. The Buddha was often referred to as ‘the samaṇa Gotama.’ (D.I,4).

There was a great deal of religious switching at the 5 th and 4 th centuries BCE. The Buddha himself was the disciple of two different teachers, Ālāra Kālāma and Uddaka Rāmaputta, during his six-year search for truth (M.I,164-5). Early in the Buddha’s career three famous brothers, the Kassapas, who were the leaders of a band of Jaṭilas, became his disciples bringing all their followers with them (Vin.I,24-5). It was this incident more than any other that drew widespread attention to the Buddha so soon after he started teaching. The two men who later became Buddha’s senior disciples, Sāriputta and Moggallāna, had both been Ajīvakas before becoming Buddhists. Occasionally, those who had been the Buddha’s disciples joined other sects, Sunakkhatta being an example of this (D.III,2).

Sramana Tradition: Its History and Contribution to Indian Culture, G. C. Pandey, 1978.