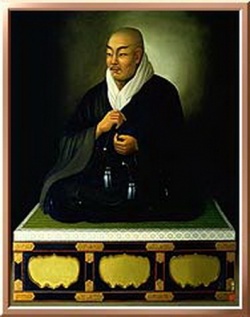

Shinran Shonin

Shinran Shonin (1173-1262) was the founder of Shin Buddhism. He was born at the close of the Heian period, when political power was passing from the imperial court into the hands of warrior clans. It was during this era when the old order was crumbling, however, that Japanese Buddhism, which had been declining into formalism for several centuries, underwent intense renewal, giving birth to new paths to enlightenment and spreading to every level of society.

Shinran Shonin was the founder of Shin Buddhism.

Life of Inspiration

Shinran was born into the Hino family and his father at one time served at court. At the age of nine, however, Shinran entered the Tendai temple on Mt. Hiei, where he spent twenty years in monastic life. From the familiarity with Buddhist writings apparent in his later works, it is clear that he exerted great effort in his studies during this period. He probably also performed such practices as continuous recitation of the nembutsu for prolonged periods.

Conversion

After twenty years, however, he despaired of ever attaining awakening through such discipline and study; he was also discouraged by the deep corruption that pervaded the mountain monastery. Years earlier, Honen Shonin (1133-1212) had descended Mt. Hiei and begun teaching a radically new understanding of religious practice, declaring that all self-generated efforts toward enlightenment were tainted by attachments and therefore meaningless. Instead of such practice, one should simply say the nembutsu, not as a contemplative exercise or means of gaining merit, but by way of wholly entrusting oneself to the great compassionate activity of the ultimate dimension, symbolized by Amida's Vow, to bring all beings to enlightenment and spiritual liberation.

When he was twenty-nine, Shinran undertook a long retreat at Rokkakudo temple in Kyoto to determine his future course. At dawn on the ninety-fifth day, Prince Shotoku , the founder of Japanese Buddhism, appeared to him in a dream. Shinran took this as a sign that he should seek out Honen, and went to hear his teaching daily for a hundred days. He then abandoned his former Tendai practices and joined Honen's movement.

Exile

At this time, however, the established temples were growing jealous of Honen, and in 1207 they succeeded in gaining a government ban on his nembutsu teaching. Several followers were executed, and Honen and others, including Shinran, were banished from the capital.

Shinran was stripped of his priesthood, given a layman's name, and exiled to Echigo (Niigata) on the northern hinder lands of the Japan Sea coast. About this time, he married Eshinni and began raising a family. He declared himself "neither monk nor layman." Though incapable of fulfilling monastic discipline or good works, precisely because of this, he was grasped by Amida's compassionate activity. Later, he chose for himself the name Gutoku, "foolish/bald one," indicating the futility of attachment to one's own intellect and goodness.

He was pardoned after five years, but decided not to return to Kyoto. Instead, in 1214, at the age of forty-two, he made his way into the Kanto region, where he spread the nembutsu teaching for twenty years, building a large movement among the peasants and lower samurai.

Return to Kyoto

Then, in his sixties, Shinran began a new life, returning to Kyoto to devote his final three decades to writing. He did not give sermons or teach disciples, but lived with relatives, supported by gifts from his followers in the Kanto area. It is from this period that most of his writings stem. He completed his major work, popularly known as Kyogyoshinsho, and composed hundreds of hymns in which he rendered the Chinese scriptures accessible to ordinary people. His creative energy continued to his death at ninety, and his works manifest an increasingly rich, mature, and articulate vision of human existence that reveals him to be one of the world’s most profound and original religious thinkers. His last words were,

"Though I return to the Pure Land of Eternal Peace after my life is at an end,

Yet shall I return to this world, again and again,

Just as the waves of Wakanoura Bay return to the beach....

When you rejoice in the Nembutsu, consider that two actually rejoice

When you rejoice with another, consider that there are three,

And that other is Shinran…Thank You, Namo Amida Butsu."