Sinicizing Buddhist concepts

Since the time of Mencius, the ultimate ontological issue in China was the question of human nature and mind (which Mencius and most Chinese thinkers treated as synonyms). Pre-Han Chinese philosophers had debated whether human nature was originally good, bad or neutral. The written Chinese character for ‘nature’, xing, consists of two parts: the left side means ‘mind’ and the right side means ‘birth’, which led Chinese thinkers to debate whether human nature was determined by what one is born with, namely appetites and desires, or whether it reflects the nature of one’s mind, which in Chinese thought invariably carried an onto-ethical rather than strictly cognitive connotation. The word xin literally means ‘heart’, indicating that – unlike Western conceptions that draw a sharp line between the head and the heart – for the Chinese, thinking and feeling originated in the same bodily locus. Feeling empathy or compassion as well as rationally abstracting principles and formulating ethical codes were all activities of xin, heart-and-mind (see Xin; Xing).

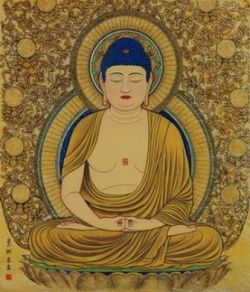

Indian Buddhism had little to say about human nature, with many forms of Buddhism rejecting the very concept of essential nature. Some of the early polemics against Buddhism in China explicitly attacked it for neglecting to address the question of human nature. The notion of Buddha-nature was developed, in part, to redress that failing. Since Indian Buddhists were deeply interested in the mind in terms of cognitive processes such as perception, thinking, attention and so on (see Mind, Indian philosophy of; Sense perception, Indian views of), it was a natural step for the Chinese to read these initially in the light of the Chinese discourse on mind, and to further develop interpretations of this material in line with Chinese concerns. Hence passages that in Sanskrit dealt primarily with epistemology or cognitive conditions often became, in their Chinese renderings, psycho-moral descriptions. The Sanskrit term ekacitta, a mind with singular focus (but literally meaning ‘one mind’) becomes the metaphysical one mind of the Awakening of Faith in Mahāyāna. Similarly, Indian and Chinese philosophers had developed very different types of causal theories. Indian Buddhists accepted only efficient causes as real, while Chinese Buddhists tended to interpret Buddhist causal theories as examples of formal causes.

Source

LUSTHAUS, DAN (1998). Buddhist philosophy, Chinese. In E. Craig (Ed.), Routledge Encyclopedia of Philosophy. London: Routledge. Retrieved May 21, 2013, from http://www.rep.routledge.com/article/G002SECT11