Six Noble Qualities of the Bodhisattva-Warrior by Mipham J. Mukpo

“We might think that helping others will drain us. But when we become bodhisattva-warriors—using our wisdom and compassion to extend our lives to others—our own suffering is relieved.”

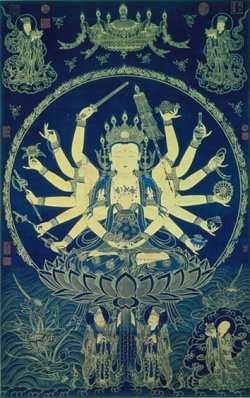

Mahayana Buddhist teachings encourage us on the path of the bodhisattva-warrior, one who is brave and confident enough to overcome self-centeredness in order to help others. The activity of the bodhisattva-warrior happens on many different levels, and bodhisattvas can manifest in all kinds of ways—even as a sun or moon. A bodhisattva could say, "I wish to be a cool breeze that gives sentient beings comfort from the heat of suffering," and manifest as the wind. That's how far the bodhisattva path extends.

Becoming a bodhisattva is a matter of opening our hearts, and that can be as simple as opening our eyes. The essence of bodhisattva activity is prajna, which means "best knowledge," "the best thing to know." The "best thing to know" is the truth. All of us want to know that. To know the truth is to see the transitory nature of who we are—the selflessness of ourselves and others. It's to see the suffering that comes from imagining we are solid and permanent entities. It's to cultivate the mind of enlightenment: love, compassion, joy and equanimity. This is the notion of prajna and the path of the bodhisattva.

Opening our eyes to the truth is the first step on the bodhisattva path. It begins with the process of meditation. In peaceful abiding, or shamatha meditation, we learn to stop, look and listen. We discover that the mind is fluid; we can always work with it. We see that when we harden ourselves, we experience turmoil and suffering. After we've practiced like this for a while, things begin to lighten up. Understanding the transitory nature of everything, we're in tune with the truth. Our minds are more relaxed and open. When we interact with other people, we can begin to go beyond our discursiveness and see the bottom line, which is that all of us want to be happy. We all want to be relieved of suffering. The truth is very simple in this way.

When we open our eyes to the truth—that people are in pain at a very basic level—we feel a natural response. This response is called compassion. It's called love. We want to help. Compassion and love have no limit, especially if we encourage their growth with the practice of stepping beyond ourselves. This is bodhisattva activity, which is endless, for as we practice this way, our courage and willingness to help others grow. Our mind and motivation only get bigger.

The way we proceed on this path is with prajna, the inquisitive mind that sees the wisdom in each situation. We practice and study to sharpen this mind so that we can know what is appropriate action. Taking the appropriate action is a powerful tool: in one moment we can cross into the mind of enlightenment. What do we do in that one moment? We move from being self-centered to considering the other person. There are six ways to do this on the bodhisattva path. They're called paramitas, a Sanskrit word that means "that which has reached other shore."

The first paramita is generosity. Instead of being selfish, we're generous. With generosity we overcome attachment. It can be as simple as saying something positive instead of something negative. When we run into an acquaintance, instead of saying, "Oh, there's so-and-so, still doing that same old thing," we can look at them saying, "There goes the Buddha." Try it. If nothing else, it will make you laugh.

Next is discipline. With discipline we know what to accept and what to reject. We know how karma works. If we're thinking only of ourselves and getting mad at everybody else, enlightenment will never come about. The way we use discipline to transport us to the other shore in a moment is to look at our mind, speech and activity with this question, "Is this taking me toward enlightenment or suffering?"

The next paramita is patience, which has a very practical purpose: it overcomes anger. Anger in a moment can destroy a lot of positive actions, because it makes our mind hard. All the flexibility and openness that we've created through meditation becomes tight and stiff. Everything becomes difficult. People ask me what to do when they feel really angry; should they do shamatha practice or tonglen (the practice of taking in others’ negative or painful energy and sending out to them positive, healing energy)? Being angry and wanting to be peaceful all of sudden doesn't usually work. If we're about to blow up, the best thing to do is just sit there, settle, breathe. The best technique may well be patience.

The next paramita is exertion, which has an element of joy. The myth of selfhood is like a veil that keeps us from seeing enlightened mind. Going beyond ourselves brings pleasure. In one moment we can wake up to the dilemma of suffering and take the happiness of others to be our own responsibility. We can exert ourselves endlessly. A bodhisattva looks up at the sky and says, "After I'm done with planet Earth, I'm going to get on that spaceship and go help all those beings on other planets." The fifth paramita is meditation. With the practice of meditation we discover our mind's inherent stability, clarity and strength. We contemplate the truth that there's no way to find this individual self that we protect, feed and clothe. We see how clinging to the illusion of solidity causes suffering. This is how we sharpen our prajna, wisdom. In order for the other paramitas to take us toward the mind of enlightenment, we need this wisdom to break down and dismantle our conceptual ideas of who we are and what we're doing. We slowly begin to understand that things are not as they seem. Compassion arises. We gain insight into our experience, which allows us to apply generosity, discipline, patience and exertion in helping others. We might think that helping others will drain us. But when we use prajna and compassion to extend our lives to others in this way, our own suffering actually becomes relieved. Just placing our mind on others is a kind of meditation. Mind is like a muscle that relaxes that way. When we begin to think about ourselves it tightens up, until we can't even help ourselves properly. But working for the happiness of others brings lightness of mind. When we know this truth, extending love and compassion is all there is to do. Then everything we encounter becomes part of our journey as practitioners of meditation. We can look at each other, at our children and at the world, and see it all as an opportunity to experience the joy of the bodhisattva path. We see this joy in the faces of great spiritual teachers and other bodhisattvas. The most basic thing is having the open and curious mind of prajna, because that's what shows us how to move forward. Bodhisattva activity is how we move forward into enlightenment.