Starbucks at the Stupa: Neo-Buddhism

Starbucks at the Stupa: Neo-Buddhism

By Indrajala (Jeffrey Kotyk)

In contemporary Japanese there is a relatively new term Shin Shūkyō 新宗教 which is nominally translated as “New Religion”. It often comes with a negative connotation in common speech (something like “cult” in English), though scholars objectively characterize such movements as simply possessing certain characteristics that differentiate them from older more traditional religious groups. Given the East Asian context, the term more specifically refers to movements with religious and philosophical elements originating from that region of the world, though not restricted to Japan.

Looking through several Japanese dictionaries and considering my own observations I would highlight some features of a Shin Shūkyō as follows.

- Generally initiated by a charismatic leader during the 19th or 20th centuries who founds the tradition on older religious elements from Christianity, Shintō, Daoism and/or Buddhism before adding their own innovative ideas and reforms.

- Possesses a stated interest in salvation in the present world and perhaps a very strong interest in modernization, largely driven by past or present turbulence, be it social or political.

- Makes a clear effort to be global and embracing of various cultures. They might fail at this, but nevertheless internationalization is still an evident point on their agenda.

- Exclusive in the sense of discouraging their members from participating in outside religious groups or receiving teachings from outsiders.

- Assertive proselytizing and propaganda efforts. Strong personality cult surrounding the founder discernible and tied in with their propaganda.

I think any organization matching this description and identifying themselves as Buddhist might be identified as a Neo-Buddhism to distinguish it from older developments.

For example, in contrast to Neo-Buddhism(s), older forms of Buddhism generally do not make noteworthy efforts at proselytizing. They generally trace their lineages back to long dead ancestors and actively aggrandize ancient masters more than modern individuals. Proselytizing and propaganda efforts are also minimal if not non-existent.

Traditional Theravāda communities generally raise Śākyamuni Buddha above everyone else past and present. They might then defer to Buddhaghoṣa as a secondary canonical figure. Modern day masters will be venerated, but not to the extent you see in Neo-Buddhism(s).

We might also consider that the flourishing of Sōtō Zen in the west is largely to be attributed to a few maverick Zen monks from Japan and a whole lot of westerners who have translated the texts, practiced zazen extensively and built the institutions rather than a core policy of expansion from the central Sōtō administration. Foreigners are welcome to enrol at Komazawa University (Sōtō's university in Tokyo) as I did or train at a prominent Zendō in Japan, but as far as I know the upper echelons of leadership do not actively encourage this. They are certainly not opposed, but it is simply not on their priority list. Likewise, in Dōgen's day he went to China on his own to get the teachings. China's Chan masters at the time did not seem to have any policy of sending their monks abroad to spread their lineages and have people join them. You can even see the emphasis on the past in the Sōtō museums at Komazawa University and Sōji-ji in Yokohama – there are mostly images of long dead masters alongside Dōgen, as if present developments and leaders are ignored except for maybe a small tribute to DT Suzuki.

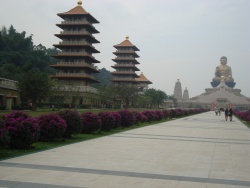

So which major Buddhist organizations in Asia might qualify as Neo-Buddhist? In my mind, the most prominent example of a Neo-Buddhism is Foguang Shan (FGS), based out of Taiwan but with a global network of well-managed temples plus their international network called Buddha's Light International.

In the last few years I have had some dealings with the organization both directly and indirectly. I have also met a number of former FGS monastics (Taiwanese and non-Chinese) who for various reasons abandoned the organization and were willing to tell me a lot of their thoughts, both positive and negative, on FGS. I further know some non-FGS persons who have had dealings with them. I consider their testimonies reliable and valuable as most of them were insiders to varying degrees. They are also all devoted Buddhist monks and nuns who I trust would not lie.

In 2010 I participated in FGS's month long summer student program called the Woodenfish Program where we got a taste of their version of monastic life before going through a week long Chan retreat followed by an international youth seminar which many of the western students ditched in favour of going to the beach to smoke, eat cheeseburgers and maybe express romantic affections (all of which were strictly forbidden during the program and were said to result in immediate ejection). All the participants received US$500 cash to offset travel expenses. We were told this was “a gift from Master Xingyun”.

It was this Master Xingyun (born 1927 in Jiangsu, China), otherwise romanized as Hsing Yun, who founded the organization and started building FGS monastery in 1967. Following this FGS monasteries were rapidly built around the world in such places like Hong Kong, Malayasia, Singapore, USA, South Africa, UK, Canada, Japan and elsewhere. They recently inaugurated their new university Foguang University in Yilan, Taiwan, too. In the English speaking Buddhist world it is not a well-known organization, though it is somewhat influential amongst the Chinese diaspora and the greater Buddhist world around Asia. In Taiwan Xingyun is a household name.

Xingyun has led an active life as an administrator and has attracted tens of thousands of monastic and lay devotees. He is the symbolic figurehead of the worldwide organization and in my observations there is a strong personality cult surrounding him. In the Chinese speaking world a lot of devotees find him charismatic and appealing. He is normally referred to in Chinese as a da-shi 大師, which for better or worse in English is normally rendered as “Grand Master”. The museum at FGS in Taiwan describes him in glowing, almost non-human, terms and their propaganda materials likewise are no different.

On the main website's biography page they describe his childhood as follows:

- 1. Born in a rural village, the poverty of his family and influence of his maternal grandmother helped him nurture a compassionate and hardworking nature.

- 2. Being Hardworking: He would tidy up the house while his family was out to work, hoping to give his parents a pleasant surprise when they got home. His experiences in boiling water, cooking meals,chopping woods, herding cattles, ploughing fields and so on, enabled him to focus on being practical rather than theoretical.

- 3. Being Compassionate: Venerable Master's maternal grandmother was a pious and devoted Buddhist who had a compassionate heart. Being influenced by her, he never dared to kill a mosquito, a fly, or an ant, and was very loving towards small animals. He once took care of an injured chick until it was able to lay eggs. Injured pigeons and squirrels could often be found inside the Founding Master's House up at Fo Guang Shan. The number of animals that have been taken care by him over the past thirty years is hard to keep count of. Fo Guang Shan went from a place where no birds laid their eggs to today's home to hundreds of birds.

Apparently as a young man he was so important the military even escorted him around:

- 3. Between the age of 23 and 30, he visited various Buddhist temples throughout Taiwan. He has taken many kinds of transportation vehicles and received military invitation to give Dharma talks to the armed forces of the land, sea, and air, where he was escorted by military aircrafts and battleships.

What is remarkable about this comical hagiography is the emphasis given to just one man, who is still living, rather than his lineage (he is identified by FGS as the 48th patriarch of the Linji school; see the site). Traditionally in Chinese Buddhism, as one also finds in Japan incidentally, the emphasis is laid on the lineage and patriarchs, i.e., dead masters who cannot defend themselves against aggrandized hagiographies.

When I was at Woodenfish I got to attend two audiences with Xingyun. Prior to this I had read Stuart Chandler's work on FGS entitled Establishing a Pure Land on Earth: The Foguang Buddhist Perspective on Modernization and Globalization, which is a key work on the group as Chandler spent a few years at the main temple doing a thorough anthropological study. What struck me reading this was Xingyun's non-opposition to the death penalty. Chandler writes,

Capital punishment is also permissible in Master Xingyun's view. In fact, according to the law of cause and effect, executing a murder fulfills the natural consequence of that person's act. So long as the executioner holds no enmity or grudge against the person being executed, little individual karmic effect will adhere, for he or she is merely carrying out the country's law. Those involved in handing down the death penalty may even accumulate positive karma if their intentions are as pure as those of Shakyamuni Buddha, who, according to the Jataka tales, had, in one of his previous lives, killed a bandit to prevent him from massacring five hundred merchants. (p144)

So, I had the opportunity to put the question to Xingyun and I asked him if he supported or opposed the death penalty. He initially appeared shocked and a few moments later he explained his reasoning that if you kill someone, why can't you be killed? While Buddhists supporting the death penalty is nothing new, his little nuanced straightforward view on the matter, especially as an eminent leader in the Chinese Buddhist world, perhaps reveals a lack of western liberal influences in his thought.

FGS, like several other Chinese Buddhist organizations, embraces an ideology called Humanistic Buddhism. Humanistic Buddhism was formulated in the 20th century by figures like Yinshun, Taixu and later developed by Xingyun, Shengyan and others. The basic premise is that instead of seeking rebirth in a distant pure land, we as Buddhists might build or bring the pure land here. The FGS website states the following about Xingyun:

- In Taiwan, he began fulfilling his long-held vow of promoting Humanistic Buddhism, which takes to heart spiritual practice in daily life. With an emphasis on not needing to "go some place else" to find enlightenment, we can realize our true nature in the here and now, within this precious human birth and this world. When we actualize altruism, joyfulness, and universality, we are practicing the fundamental concepts of Humanistic Buddhism. When we give faith, hope, joy, and service, we are helping all beings, as well as ourselves. For nearly a half century, Venerable Master Hsing Yun has devoted his efforts to transforming this world through the practice of Humanistic Buddhism.

Humanistic Buddhism is essentially aimed at building a Buddhist utopia on earth, which strangely is not so unlike communists who would make a utopia out of an oppressed world. This corresponds to the aforementioned definition of a Neo-Buddhism where there is a stated interest in salvation in the present world rather than an aim at gaining transcendental experiences or postmortem benefits (like a favourable rebirth).

While the process of rationalization and disenchantment following modernization has not been so strong in Asia as it has been in the western world, there is still a discernible increased desire for religious projects to present immediately tangible results. This might be tied in with secularization and a lack of concern for postmortem possibilities, hence less interest in merit making to secure a favourable rebirth (these beliefs still exist, just less so than in previous eras). The same process can be seen at work in other Buddhist countries like Sri Lanka where Buddhist organizations often justify their existence by doing immediately visible social work in the community.

In relation to this, Humanistic Buddhism generally asserts an idea of “work as practice” and this usually means traditional practices, such as meditation, are relegated to secondary importance in favour of social and administrative work. Some of the former FGS monastics I know complained that during their time with the organization they were forced to constantly work without having time to engage in traditional practices. The needs of the organization are in part met through the unpaid labour of volunteer monastics. One present FGS monk has explained to me their ordination system as being an “investment” where the organization invests resources in someone and expects a return on what they put into them. The management, he explained, hates it when someone gets a free education from them and then leaves.

Another related feature is that monastics are expected to stay within FGS for life. Anyone who leaves without permission is permanently exiled and their colleagues within the organization are not supposed to continue communicating with them. One monk did however inform me that a nun was let back in after she crawled on her hands and knees through the dining room and begged for forgiveness. This is quite different from the older Chinese system where you could basically sign into any public monastery and come and go as you pleased. Ordination halls existed, but were not monopolized by any overarching organization. It was just where you went for a few weeks as an ordinand to get formally ordained.

The older decentralized system in China was that of master and disciples. A novice would study under their master and later go their own way before taking on their own disciples. FGS is similar to the Catholic Church in having a centralized administrative system with a charismatic figurehead being deferred to when making major decisions. Education of monastics is conducted in programs not so unlike a Catholic seminary. For various reasons, the old novice-apprentice system was largely abandoned in Taiwan in favour of the Buddhist college system with well-defined requirements, curriculum and strict expectations, though some older monks and nuns were still brought up through the older novice-apprentice system.

The old model was for better or worse far less homogenized and disciplined. Not so long ago I met a former FGS nun who was watching television. She joked that at FGS she was not allowed to watch TV. She also mentioned restrictions on travel and the severely strict regulations she was subject to.

A few months later I met yet another nun who explained how inside the nun's quarters there was internal policing where they would go into rooms and photograph contraband items and then confront the person in question. In one case, a Tibetan thangka was photographed and the nun in question was told this was heretical and not permitted. This sort of approach is of course not universal in modern Taiwan. You can find plenty of Chinese monks and nuns who take an interest in Tibetan Buddhism and this is visibly clear at some talks in India given by His Holiness the Dalai Lama. The Catholic influences in this respect should be apparent: an emphasis on orthodoxy and exclusion of the heterodox, even if they are Buddhist.

It was a few months ago that I paid a visit to FGS again with a friend to show him what at least one form of Buddhism in Taiwan looks like. I was also interested in seeing their Buddha Memorial Center, which I had seen a few years prior when it was under construction. As the story goes Xingyun received a genuine Buddha tooth relic from Kunga Dorje Rinpoche following the ordination ceremonies that had been conducted in Bodhgaya in 1998. The official FGS history states the following (see here):

- Buddha's tooth relic was once kept at the Namgyal Monastery in Tibet. During the Cultural Revolution, however, the monastery was destroyed, and Kunga Dorje Rinpoche found the precious tooth, one of the only three Buddha's tooth relics in the world. To protect this holy relic, he fled to India, a journey that was fraught with much hardship. Once there, several highly cultivated Tibetan rinpoches authenticated the relic and advised him to build a pagoda so that the public could pay their respects and make offerings to the Buddha's tooth relic.

- Unfortunately, Kunga Dorje Rinpoche never got the opportunity to build a pagoda as he had vowed, because old age caught up with him. In February 1998, Venerable Master Hsing Yun of Fo Guang Shan Monastery held the Bodhgaya International Full Ordination in India, which drew the attention of Kunga Dorje Rinpoche. He, together with twelve highly cultivated Tibetan rinpoches, reached a consensus to donate the Buddha's tooth relic to Venerable Master Hsing Yun. They knew that Venerable Master Hsing Yun had embraced a vow to benefit all sentient beings in the universe. The rinpoches felt assured that he would be able to perpetuate the Dharma and let the value of the relic be recognised once again. Because of these causes and conditions, the Buddha's tooth relic was escorted to Fo Guang Shan in Taiwan on 8 April 1998.

The story, at least to me, sounds dodgy and even comical. Who were these "highly cultivated" rinpoches and did they really think so highly of Xingyun who has vowed to benefit all sentient beings in the universe? One senior monk in Bodhgaya that I spoke to also related his doubts about the authenticity of this tooth, stating he was unaware of any history behind it. John Buescher in "The Buddha's Conventional and Ultimate Tooth" (Changing Minds: Contributions to the Study of Buddhism and Tibet in Honor of Jeffrey Hopkins) details how at the time the Tibetans, from Sakya lamas to His Holiness the Dalai Lama and his staff, knew nothing of this tooth or "Kunga Rinpoche". As it turns out this Kunga figure was just a monk who had been living in Nepal for decades:

- He is a monk, a Sa skya monk, named Kunga. But he's not a lama, not a rin po che. And he's not from India, but from Nepal, where he has lived for decades. On the day of the handover of the tooth, this monk Kunga flew to Bangkok, not from New Delhi, but from Kathmandu, and he flew out of Taiwan almost immediately after the ceremony at Chiang Kai-shek Airport. All this would explain why no one, especially no one in India, had ever heard of him before.

From a critical point of view, this official narrative sounds a bit too good to be true, but nevertheless it generated plenty of interest in Taiwan and elsewhere. It was cause for building the enormous stūpa and shopping complex housing the relic. An FGS monk told me that the main purpose behind the complex was to ensure that FGS would continue receiving funding after Xingyun passes away at it is anticipated donations to the organization will significantly drop. It is located in a neighbouring valley next to the main FGS temple complex.

It has a wide open parking lot suitable for plenty of tour buses. Walking up towards the first building you enter a shopping mall before moving onward to the path leading to the stūpa itself. On the left-hand side of there is a fully operational Starbucks cafe, which are now seemingly ubiquitous around much of Taiwan. This is especially remarkable given how such a global franchise represents aggressive capitalism and consumerism. I would venture to say that a lot of more traditionally minded Buddhist organizations would frown on having a Starbucks outlet inside a complex intended to house and celebrate a Buddha relic. Nevertheless, the mall also has a gourmet chocolate shop, vegetarian restaurant, Seven Eleven (no alcohol or meat available of course) and several gift shops. FGS is a capital intensive religious organization and visibly endorses the modern consumer lifestyle, which again contrasts with the former small-scale decentralized system of autonomous temples which had to look after their finances through donations and priestly services (prayers for the dead, rites for longevity, etc.).

This endorsement is even more evident when you walk through the doors into the stūpa facility and see yet another gift shop on the left and signs pointing to another cafe (not Starbucks). My personal feeling at that point was that this Buddha Memorial Center was only partly to celebrate the Buddha – it seemed to me that one major point of it all was to generate income, which confirmed what the FGS monk had told me earlier. Deep inside the building there is indeed a tooth encased high above in a carpeted room where the pilgrims gather. As they would be in most Buddhist temples, donation boxes are strategically placed at the front of such an important room.

At that point one of the FGS nuns on duty surveyed my friend about his thoughts. She then cheerfully discussed how modern the new facility was and asked what he thought about it. This typifies another part of the aforementioned definition of a Neo-Buddhism: concern, even obsession, for modernization and adaptation to contemporary circumstances. This is different from traditional forms of Buddhism which organically evolve rather than declaring their intention to adapt and conform to changing circumstances.

Of course FGS is not the only form of Neo-Buddhism that has come to prominence in recent times. Tzu Chi, founded by Venerable Zhengyan, is another noteworthy Chinese organization based in Taiwan with its international network of facilities, personality cult around the founder and private university.

Another more well-known organization from Japan is Sōka Gakkai International (SGI), a lay Buddhist organization based on the teachings of the 13th century monk Nichiren. It traces itself back to Tsunesaburō Makiguchi who in 1930 founded Sōka Gakkai. Its expansionism across the globe came under the third president Daisaku Ikeda who founded SGI, the international organization.

My first contact with the organization was as an undergrad at the University of Manitoba where I was invited into the SGI student office. We chatted for a bit and then I was asked to chant with them. I was unprepared for this and could only sit still while they loudly recited Namu Myō Hō Renge Kyō for a few minutes. They then explained how chanting had changed their lives for the better. At the time I was not so familiar with Buddhism in general, but felt uncomfortable and never returned. However, later on in Japan I was cheerfully invited to talks by Daisaku Ikeda, though my research into the group and its activities had only affirmed my discomfort with the organization at that point.

SGI diligently attempts to recruit people. They will have parties where they casually invite newcomers to attend and then ask everyone to join hands and chant. Proselytizing is evidently a key component to their expansionist strategy. They furthermore have made inroads abroad and become a truly international organization, translating their material and making their project available to various cultures outside Japan, even as far as India. This is much like FGS which has branch temples in foreign countries, but also recruit foreigners into their monastic college from India and Africa.

Traditional forms of Japanese and Chinese Buddhism naturally have gone abroad as well, but clergy usually followed immigrants or arrived in sparse numbers at the request of devotees abroad, their temples often remaining “ethnic temples” not catering to the greater community for any number of years, if ever.

SGI Buddhist doctrine as declared on their public website is rather secularized sounding and, from a more traditional approach, highly reformed. They are interested in immediate this-worldly benefits – for instance, the SGI homepage prominently states "Engaged Buddhism for a Changing World" (not unlike the socially engaged programs of Humanistic Buddhism out of Taiwan). On their FAQ they also speak on behalf of Buddhists and in response to the question of "What is enlightenment?" they state, "Buddhists believe that each individual has limitless positive potential and the power to change his or her life for the better. Through their practice people can become more fulfilled and happier and also able to contribute more to the world."

In respect to desire they state, "Desires are integral to who we are and who we seek to become. Were we to completely rid ourselves of desire, we would undermine our individual and collective will to live."

For newcomers such a message would not doubt sound easier on the ears than the traditional line of the Buddha concerning the need to abandon desire and gain freedom from passions. The site presents a rather comforting and appealing message, which I would imagine is specifically crafted as such so as to attract new recruits.

SGI is closely tied to the New Kōmeitō Party and a lot of Japanese are aware SGI is heavily involved in politics. SGI also has private universities. One is in America. During my three years in Japan I often heard negative statements about SGI and their political activities from Japanese people. There are also communities which denounce the whole organization as a cult.

I believe SGI is easily identified as a Shin Shūkyō given the stated definition above. It would also thus qualify as a Neo-Buddhism. Generally speaking, Japanese scholars would regard it as such as well.

We might wonder if Neo-Buddhism(s) will become increasingly popular and influential in the years to come. Is the future of Buddhism, at least in Asia, going to be dominated by such organizations? Will older institutions take note of their success and emulate them? Having a highly organized and centrally-administered institution capable of acquiring and rapidly moving vast sums of capital would no doubt appeal to a lot of ambitious Buddhist leaders. The inevitable organizational maintenance (internal politics) and the opportunism that comes with such favourable conditions are challenges that are not likely to be addressed in public discourse however. The larger an organization grows, the greater their internal problems become. The natural result in a given human society under such circumstances is to increase resources devoted to policing and legitimization. Insisting on orthodox doctrine, as Neo-Buddhisms usually do, also leads to rigidity and ironically despite all the talk of adapting to modernity such inflexibility has been the undoing of many a community past and present.

I expect Neo-Buddhist organizations to continue growing for the foreseeable future and other groups, particularly within Theravada and Tibetan Buddhism, to emulate them in various ways as a means of acquiring their own capital and membership bases with which to expand their institutions and influence. If successful, they will also have gain further power in the political sphere, as SGI has done with their political party.

One ultimate flaw, however, with capital intensive Buddhism is that if economic problems arise then, regardless of whatever sum of money exists in the bank, assets can quickly be erased and the means to maintain just the status quo, let alone expansionist activities, will quickly vanish. Decentralized and autonomous communities with relatively small membership bases are less efficient than capital intensive mega-organizations, but nevertheless they are generally more resilient and adaptive given their individual capacity to make decisions freely and direct themselves. Also, if one fails, then there are still others which will survive.