Difference between revisions of "Svasaṃvedana"

(Created page with "thumb|250px|Indian philosopher [[Dignaga]] In Buddhist philosophy, Svasaṃvedana (also Svasaṃvitti) is a term which refers to the self-reflexive nature...") |

|||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

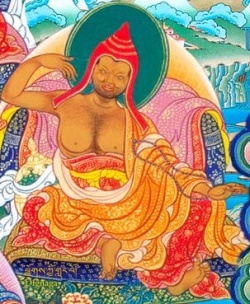

[[File:Dignaga.JPG|thumb|250px|Indian philosopher [[Dignaga]]]] | [[File:Dignaga.JPG|thumb|250px|Indian philosopher [[Dignaga]]]] | ||

| − | In Buddhist | + | In [[Buddhist Philosophy]], Svasaṃ[[Vedana]] (also [[Svasaṃvitti]]) is a term which refers to the self-reflexive nature of consciousness. Introduced by the Indian philosopher Dignaga, it is an important doctrinal term in Indian [[Mahayana]] thought and [[Tibetan Buddhism]]. It is also often translated as self apperception. |

| − | + | Svasaṃ[[Vedana]] is at the root of a major doctrinal disagreement in Indian [[Mahayana Buddhism]]. While defended by the [[Yogacara]] thinkers such as Dharmakirti and the eclectic Santaraksita, it was attacked by 'Prasangika [[Madhyamika]]' thinkers such as Candrakirti and Santideva. Since in Mādhyamika thought all dharmas are empty of inherent essence ([[Svabhava]]), they argued that consciousness could not be an inherently reflexive ultimate reality since that would mean it was self validating and therefore not characterized by emptiness. | |

| − | In Tibetan Buddhism there are various competing views regarding | + | In [[Tibetan Buddhism]] there are various competing views regarding svasaṃ[[Vedana]] (Tibetan: Ranggi [[Rig pa]]). |

| − | In the Nyingma school's Dzogchen tradition, | + | In the Nyingma school's Dzogchen tradition, svasaṃ[[Vedana]] is often called 'the very nature of mind' (sems kyi chos nyid) and metaphorically referred to as 'luminosity' (gsal ba) or 'clear light' ('od gsal). A common Tibetan metaphor for this reflexivity is that of a lamp in a dark room which in the act of illuminating objects in the room also illuminates itself. Dzogchen meditative practices aim to bring the mind to direct realization of this luminous nature. In Dzogchen (as well as some Mahamudra traditions) Svasaṃ[[Vedana]] is seen as the primordial substratum or ground (gdod ma'i gzhi) of mind. |

| − | Following Je Tsongkhapa's interpretation of the Prasaṅgika Madhyamaka view, the Gelug school completely denies even the conventional and the ultimate existence of reflexive awareness. This is one of Tsongkhapa's "eight difficult points" that distinguish the Prasaṅgika view from others. The Nyingma philosopher Jamgon Ju Mipham Gyatso defended the conventional existence of reflexive awareness as per the Madhyamaka two truths doctrine. According to Mipham, the Prasangika critique of reflexive awareness only applied to it's ultimate inherent reality and not it's conventional status. | + | Following [[Je Tsongkhapa]]'s interpretation of the [[Prasaṅgika]] [[Madhyamaka]] view, the Gelug school completely denies even the conventional and the ultimate existence of reflexive awareness. This is one of [[Tsongkhapa]]'s "eight difficult points" that distinguish the [[Prasaṅgika]] view from others. The Nyingma philosopher [[Jamgon Ju Mipham Gyatso]] defended the conventional existence of reflexive awareness as per the [[Madhyamaka]] two truths doctrine. According to Mipham, the Prasangika critique of reflexive awareness only applied to it's ultimate inherent reality and not it's conventional status. |

{{W}} | {{W}} | ||

| − | + | [[Category:Buddhist Philosophy]] | |

[[Category:Buddhist philosophical concepts]] | [[Category:Buddhist philosophical concepts]] | ||

[[Category:Buddhist Terms]] | [[Category:Buddhist Terms]] | ||

Revision as of 05:10, 23 February 2013

In Buddhist Philosophy, SvasaṃVedana (also Svasaṃvitti) is a term which refers to the self-reflexive nature of consciousness. Introduced by the Indian philosopher Dignaga, it is an important doctrinal term in Indian Mahayana thought and Tibetan Buddhism. It is also often translated as self apperception.

SvasaṃVedana is at the root of a major doctrinal disagreement in Indian Mahayana Buddhism. While defended by the Yogacara thinkers such as Dharmakirti and the eclectic Santaraksita, it was attacked by 'Prasangika Madhyamika' thinkers such as Candrakirti and Santideva. Since in Mādhyamika thought all dharmas are empty of inherent essence (Svabhava), they argued that consciousness could not be an inherently reflexive ultimate reality since that would mean it was self validating and therefore not characterized by emptiness.

In Tibetan Buddhism there are various competing views regarding svasaṃVedana (Tibetan: Ranggi Rig pa).

In the Nyingma school's Dzogchen tradition, svasaṃVedana is often called 'the very nature of mind' (sems kyi chos nyid) and metaphorically referred to as 'luminosity' (gsal ba) or 'clear light' ('od gsal). A common Tibetan metaphor for this reflexivity is that of a lamp in a dark room which in the act of illuminating objects in the room also illuminates itself. Dzogchen meditative practices aim to bring the mind to direct realization of this luminous nature. In Dzogchen (as well as some Mahamudra traditions) SvasaṃVedana is seen as the primordial substratum or ground (gdod ma'i gzhi) of mind.

Following Je Tsongkhapa's interpretation of the Prasaṅgika Madhyamaka view, the Gelug school completely denies even the conventional and the ultimate existence of reflexive awareness. This is one of Tsongkhapa's "eight difficult points" that distinguish the Prasaṅgika view from others. The Nyingma philosopher Jamgon Ju Mipham Gyatso defended the conventional existence of reflexive awareness as per the Madhyamaka two truths doctrine. According to Mipham, the Prasangika critique of reflexive awareness only applied to it's ultimate inherent reality and not it's conventional status.