THE SHADOW OF THE DALAI LAMA: SEXUALITY, MAGIC AND POLITICS IN TIBETAN BUDDHISM; THE DALAI LAMA (AVALOKITESVARA) AND THE DEMONESS (SRINMO), Part 2

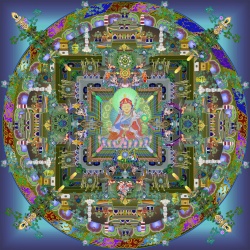

Alongside the “time tower” she built a huge metal pillar (the so-called “heavenly axis”). This was supposed to depict Mount Meru, the center of the Buddhist universe. Just as the tiantang symbolized control over time, the metallic “heavenly axis” announced the Empress’s control of space. Correspondingly her palace was also considered to be the microcosmic likeness of the entire universe. She declared her capital, Liaoyang, to be not just the metropolis of China, but also the domicile of the gods. Space and Time were thus, at least according to doctrine, firmly in Wu Zetian’s hands.

It will already have occurred to the reader that the religious/political visions of Wu Zetian correspond to the spirit of the Kalachakra Tantra in so many aspects that one could think it might have been a direct influence. However, this ruler lived three hundred years before the historical publication date of the Time Tantra. Nevertheless, the influence of Vajrayana (which has in fact been found in the fourth century in India) cannot be ruled out. Hua-yen Buddhism, from the ideas of which the Empress derived her philosophy of state, is also regarded as “proto-tantric” by experts: “Thus the Chou-Wu theocracy [of the Empress) is the form of state in China which comes closest to a tantric theocracy or Buddhocracy: the whole world is considered as the body of a Buddha, and the Empress who rules over this sacramentalized political community is considered to be the highest of all Buddhas and Bodhisattvas” (Brück and Lai, 1997, p. 630). [6]

Although no historical connection between the Kalachakra Tantra and the “proto-tantric” world view of Wu Zetian can be proved, striking parallels in the history of ideas and symbols exist. For example, alongside the claim to the “world throne” as Chakravartin, the implied control over time and space, we find a further parallel in Wu Zetian’s grab for the two heavenly orbs (the sun and moon) which is characteristic of the Time Tantra. She let a special Chinese character be created as her own name which was called “sun and moon rising up out of the emptiness” (Franke, 1961, p. 415).

But the final intentions of the two systems are not compatible. The Empress Wu Zetian is hardly likely to have striven towards the Buddhocracy of an androcentric Lamaism. In contrast, it is probable that gynocentric forces were hidden behind her Buddhist mask. For example, she officially granted her female (!) forebears bombastic titles and epithets of “Mother Earth” (Franke, 1961, p. 415). In the patriarchal culture of China this feminist act of state was perceived as a monstrous blasphemy. Hence, with reference to this naming, we may read in a contemporary historical critique that, “such a confusion of terms as that of Wu had not been experienced since records began” (Franke, 1961, p. 415).

The unrestrained ruler usurped for herself all the posts of the masculine monastic religion. In her hunger for power she even denied her femininity and let herself be addressed as “old Buddha lord” — an act which even today must seem evilly presumptuous for the androcentric Lamaists. At any rate it was seen this way by an exile Tibetan historian who, a thousand years after her death, portrayed the Chinese Empress as a monstrous, man-eating dragon obsessed with all depravities. “The Empress Wu,” K. Dhondup wrote as recently as 1995 in the Tibetan Review, “one of the most frightening and cruel characters to have visited Chinese history, awakened her sexual desire at the ripe old age of 70 and pursued it with such relentless zeal that the hunger and voracity of her sexual fulfillment into her nineties became the staple diet of street whispers and gossips, and the powerful aphrodisiacs that she medicated herself gave her youthful eyebrows ...” (Tibetan Review, January 1995, p. 11).

Did Wu Zetian stand in religious and symbolic competition with the cosmic ambitions of the ruler of the great Tibetan kingdom of the time? We can only speculate about that. Aside from the fact that she was involved in intense wars with the dreaded Tibetans, we know only very little about relations between the “world views” of the two countries at the time of her reign. It is, however, of interest for our “symbolic analysis” of inner-Asian history that the Lamaist historians posthumously declared the Tibetan king, Songtsen Gampo, who died forty years before the reign of Wu Zetian in the year 650, a Chakravartin. It was Songtsen Gampo (617-650) — the reader will recall — who as the incarnation of Avalokiteshvara nailed the mother of Tibet (Srinmo) to the ground with phurbas (ritual daggers) so as to build the sacred geography of the Land of Snows over her.

Behind the life story of Wu Zetian shines the archetypal image of Guanyin as the female, Chinese opponent to the male, Tibetan Avalokiteshvara. She herself pretended to be the incarnation of a Buddha (Vairocana or Maitreya), but since she was a female it is quite possible that she was the historical phenomenon which occasioned Avalokiteshvara’s above-mentioned sex change into the principal goddess of Chinese Buddhism (Guanyin).

At any rate Songtsen Gampo and Wu Zetian together represent the cosmic claims to power of Avalokiteshvara and Guanyin. We can regard them as the historical projections of these two archetypes. Their metapolitical competition is currently completely overlooked in the conflict between the two countries (China and Tibet), which leads to a foreshortened interpretation of the Tibetan/Chinese “discordances”. In the past the mythical dimensions of the struggle between the “Land of Snows” and the “Middle Kingdom” have never been denied by the two parties; it is just the western eye for “realpolitik” cannot perceive it.

Wu Zetian was not able to realize her Buddhist gynocentric visions. In the year 691 the tiantang (time tower) and the clock within it were destroyed in a “terrible” storm. Her reign was plunged into a dangerous crisis, then, as several influential priests claimed, this “act of God” showed that the gods had rejected her. But she retained sufficient power and political influence to be able to reassemble the tower. However, in 694 this new Tiantang was also destroyed, this time by fire. The court saw a repetition of the divine punishment in the flames and concluded that the imperial religious claim to power had failed. Wu Zetian had to relinquish her messianic title of “Buddha Maitreya” from then on.

Ci Xi (Guanyin) and the Thirteenth Dalai Lama (Avalokiteshvara)

One thousand years later, the cosmological rivalry between China (Guanyin) and Tibet (Avalokiteshvara) was tragically replayed in the tense relation between the Thirteenth Dalai Lama and the Empress Dowager Ci Xi (1835-1908).

Ci Xi appeared on the political stage in the year 1860. Like her predecessor, Wu Zetian, she started out as a noble-born concubine of the Emperor, and even as a seventeen year old she had worked her way up step by step through the hierarchy of his harem and bore the sole heir to the throne. The imperial father, Emperor Xian Feng, died shortly after the birth, and the ambitious mother of the new son of heaven took over the business of governing the country until he came of age, and de facto beyond that. When her son died suddenly at the age of 18 she adopted her nephew, who ascended the Dragon Throne as Emperor Guangxu but likewise remained completely under her influence until his death.

Officially, Ci Xi supported Confucianism, but privately, like many members of the Manchu dynasty (1644-1911) before her, she felt herself attracted to the Lamaist doctrine. She was well-versed in the canonical writings, wrote Buddhist mystery plays herself, and had these performed by her eunuchs. Her apartments were filled with numerous Buddha statues and she was a passionate collector of old Lamaist temple flags. Her favorite sculpture was a jade statue of Guanyin given to her by a great lama. She saw herself as the earthly manifestation of this goddess and sometimes dressed in her robes. "Whenever I have been angry, or worried over anything,” she said to one of her ladies in waiting, "by dressing up as the Goddess of Mercy it helps me to calm myself and to play the part I represent ... by having a photograph taken of myself dressed in this costume, I shall be able to see myself as I ought to be at all times” (Seagrave, 1992., p. 413).

Ci Xi and attendants

Such dressings-up were in no sense purely theatrical, rather Ci Xi experienced them as sacred performances, as rituals during which the energy of the Chinese water goddess (Guanyin) flowed into her. She publicly professed herself to be a Buddhist incarnation and likewise affected the male title of “old Buddha lord” (lao fo yeh), a label which became downright vernacular. We are thus dealing with a gynocentric reversal of the androgynous Avalokiteshvara myth here, as in the case of the Empress Wu Zetian. Guanyin, the Chinese goddess of mercy, makes an exclusive claim for masculine control, and thus has, within the body of a woman, the gender of a male Buddha at her disposal. In the imperialist, patriarchal West, Ci Xi was, as the American historian Sterling Seagrave has demonstrated, the victim of a hate-filled, defamatory, sensationalist press who insinuated she was guilty of every conceivable crime. "The notion,” Seagrave writes, "that the corrupt Chinese were dominated by a reptilian woman with grotesque sexual requirements tantalized American men” (Seagrave, 1992, p. 268). Just like her predecessor, Wu Zetian, she became a terrible "dragoness”, a symbol of aggressive femininity which has dominated masculine fantasies for thousands of years: "By universal agreement the woman who occupied China’s Dragon Throne was indeed a reptile. Not a glorious Chinese dragon — serene, benevolent, good-natured, aquarian – but a cave-dwelling, fire-breathing Western dragon, whose very breath was toxic. A dragon lady” (Seagrave, 1992, p. 272).

Thus, in mythological terms the two Bodhisattvas, Avalokiteshvara and Guanyin, met anew in the figures of the Thirteenth Dalai Lama and the Empress Dowager. From the moment Ci Xi realized her claim to power the two historical figures thus faced one another in earnest competition and a discord which extended far beyond questions of practical politics. The chief imperial eunuch, Li Lien Ying, foresaw this conflict most clearly and warned Ci Xi several times against meeting the Tibetan god-king in person. He even referred to an acute mortal danger for both the Empress and her adoptive son, the Emperor Guangxu. The following words are from him or another courtier: “The great lama incarnations are the spawn of hell. They know no human emotion when matters concern the power of the Yellow Church” (Koch, 1960, p. 216).

But Ci Xi did not want to heed such voices of warning and peremptorily required the visit of the Hierarch from the “roof of the world”, so as to discuss with him the meanwhile internationally very complex question of Tibet. Only after a number of failed attempts and many direct and indirect threats was she able to motivate the mistrustful and cautious prince of the church to undertake the troublesome journey to China in the year 1908.

The reception for the Dalai Lama was grandiose, yet even at the start there were difficulties when it came to protocol. Neither of the parties wanted with even the most minor gesture to make it known that they were subject to the other in any way whatsoever. In the main, the Chinese maintained the upper hand. It was true that the Hierarch from Lhasa was spared having to kowtow, then after lengthy negotiations it was finally agreed that he would only have to perform those rituals of politeness which were otherwise expected of members of the imperial family — an exceptional privilege from Beijing’s point of view, but from the perspective of the god-king and potential world ruler an extremely problematic social status. Did the Thirteenth Dalai Lama revenge himself for this humiliation?

On October 30, Ci Xi and Guangxu staged a banquet in the “Hall of Shining Purple”. The Dalai Lama was already present when the Emperor cancelled at the last minute due to illness. Three days later, on the occasion of her 74th birthday, the Empress Dowager requested that the ecclesiastical dignity conduct for her the “Ceremony for the Attainment of Long Life” in the “Throne Hall of Zealous Government”. This came to pass. The Dalai Lama offered holy water and small cakes which were supposed to grant her wish for a long life. Afterwards tea was served and then Ci Xi distributed her gifts. At midday she personally formulated an edict in which she expressed her thanks to the Dalai Lama and promised to pay him an annuity of 10,000 taels. Additionally he was to be given the title of “Sincerely Obedient, through Reincarnation More Helpful, Most Excellent through Himself Existing Buddha of the Western Heavens”.

This gift and the bombastic title were a silk-clad provocation. With them Ci Xi did not at all want to honor the Dalai Lama, rather, she wished in contrast to demonstrate Tibet’s dependency upon the “Middle Kingdom”. For one thing, by being granted an income the god-king was degraded to the status of an imperial civil servant. Further, in referring to the incarnation of Avalokiteshvara as a “Sincerely Obedient Buddha”, she left no doubt about to whom he was in future to be obedient. Just how important such “clichés” were for the participants is shown by the reaction of the American envoy present, who interpreted the granting of the title as marking the end of the Dalai Lama’s political power. The latter protested in vain against the edict and “his pride suffered terribly” (Mehra, 1976, p. 20). All of this took place in the world of political phenomena.

From a metaphysical point of view, however, Guanyin Ci Xi wanted to make the powerful Avalokiteshvara her servant. The actual “match of the gods” took place on the afternoon of the same day (November 3) during a festivity to which the “Obedient Buddha” was once again invited by Her Imperial Highness. Ci Xi, as the female “old Buddha lord” dared to appear before the incarnation of the humiliated fire god, Avalokiteshvara (the Thirteenth Dalai Lama), in the costume of the water goddess Guanyin, surrounded by dancing Bodhisattvas and sky walkers played by the imperial eunuchs. There was singing, laughter, fooling around, boating, and enormous enjoyment. There had been similar such “divine” appearances of the Empress Dowager before, but in the face of the already politically and religiously degraded god-king from Tibet, the mocked patriarchal arch-enemy, the triumphal procession of Guanyin became on this occasion a spectacular and provocative climax.

The Empress Dowager probably believed herself to be protected from any attacks upon her health by the longevity ceremony which she had cajoled from the Dalai Lama the day before. In the evening, however, she began to feel unwell, and became worse the next day. Forty-eight hours later the Dalai Lama came to the Empress and handed her a statuette of the “Buddha of Eternal Life” (a variant of Avalokiteshvara) with the instruction that she erect it over the graves of the emperors in China’s east. Prince Chong, although he objected strongly because of premonition, was with harsh words entrusted by Ci Xi to do so nonetheless. When he returned to the imperial palace on November 13, the female “old Buddha lord” felt herself to be in a good mood and was fit again, but the Emperor (her adoptive son) now lay dying and passed away the next day. He had been prone to illness for years, but the fact that his death was so sudden was also found most mysterious by his personal doctors and hence they did not exclude the possibility that he had been poisoned. [7]

But the visit of His Holiness brought still more bad luck for the imperial family, just as the chief eunuch, Li Lien Ying, had prophesied. On November 15, one day after the death of the regent, the Empress Dowager Ci Xi suffered a severe fainting fit, recovered for a few hours, but then saw her end drawing nigh, dictated her parting decree, corrected it with her own hand and died in full possession of her senses.

It should be obvious that the sudden deaths of the Emperor and his adoptive mother immediately following one another gave rise to wild rumors and that all manner of speculations about the role and presence of the Dalai Lama were in circulation. Naturally, the suspicion that the “god-king” from Tibet had acted magically to get his cosmic rival out of the way was rife among the courtiers, well aware of tantric ideas and practices. On the basis of the still to be described voodoo practices which have been cultivated in the Potala for centuries, such a suspicion is also definitely not to be excluded, but rather is probable. At any rate, Avalokiteshvara the Hierarch likewise represents the death god Yama. Even the current, Fourteenth Dalai Lama sees — as we shall show — with pride a causal connection between a tantric ritual he conducted in 1976 and the death of Mao Zedong. Even if one does not believe in the efficacy of such magical actions, one must concede an amazing synchronicity in these cases. They are also, at least for the Tibetan tradition, a taken-for-granted cultural element. The Lamaist princes of the church have always been convinced that they can achieve victory over their enemies via magic rather than weapons.

What is nonetheless absolutely clear from the events in Beijing is the result, namely the triumph of Avalokiteshvara over Guanyin, the patriarch destroying the matriarch. Perhaps Guanyin had to lose this metaphysical battle because she had not understood the fine details of energy transfers in Tantrism? As Ci Xi she had grasped masculine power, as water goddess, fire, and then in her superhuman endeavors she allowed herself to be set alight by the flames of ambition. Perhaps she played the role of the ignited Candali (of the “burning water”), without knowing that it was the tantra master from the Land of Snows who had set her alight ?

But the Dalai Lama’s political plans did not work out at all. The new Regency held him in Beijing until he agreed to the Chinese demand that Tibet be recognized as a province of the Chinese Empire. England and Russia had also given the Chinese an undertaking that they would not interfere in any way in their relations with Tibet, so as to avoid a conflict with each other. Only in 1913, two years after the final disempowerment of the Manchu dynasty (1911) did it come to a Tibetan declaration of independence, and that with an extremely interesting justification. The Thirteenth Dalai Lama issued a proclamation which said literally that the Manchu throne, which had been occupied by the legal Emperor as “world ruler” (Chakravartin), was now vacant. For this reason the Tibetan had no further obligations to China and worldly power now automatically devolved to him, the Hierarch in the Potala — reading between the lines, this means that he himself now performs the functions of a Chakravartin (Klieger, 1991, p. 32).

Jiang Qing (Guanyin) and the Fourteenth Dalai Lama (Avalokiteshvara)

There is an amazing repetition of the problematic relation of the Thirteenth Dalai Lama (Avalokiteshvara) to the Empress Dowager Ci Xi (Guanyin) in the 1960s. We refer to the relation of Jiang Qing (1913–1991), the wife of Mao Zedong, to His Holiness the Fourteenth Dalai Lama. To this day the Kundun remains convinced that the chairman of the Communist Party of China was not completely informed about the vandalistic events in Tibet in which the “Red Guard” ravaged the monasteries of the Land of Snows, and that he probably would not have approved of them. He sees the Chinese attacks against the Lamaist clergy as primarily the destructive work of Jiang Qing. Mao’s companion did in fact drive the rebellion of the young to a peak without regard for her own party or the populace, significantly worsening the chaos in the whole country. In this assessment the Tibetan god-king agrees, completely unintentionally, with the official criticism from contemporary China: “During the cultural revolution the counter-revolutionary clique around ... Jiang Qing helped themselves to the left error under concealment of their true motives, and thus deliberately kicked at the scientific theories of Marxism-Leninism as well as the thoughts of Mao Zedong. They rejected the proper religious politics which the Party pursued directly following the establishment of the PR China. Thereby they completely destroyed the religious work of the Party” — it says in a Chinese government document from 1982 (MacInnis, 1993, p. 46).

In these contemporary events, so significant for the history of the Land of Snows, the feminine also appears -- in accordance with the tantric pattern and the androcentric viewpoint of the Dalai Lama -- as the radical and hate-filled destructive force which (like an uncontrollable “fire woman”) wants to destroy the Lamaist monastic state. Then in the view of the Tibetans in exile the Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution is regarded as the beginning of the “cultural genocide” which is supposed to have threatened Tibet since this time. Not without bitterness, the current god-king thus notes that the Red Guard gave Mao’s wife the chance, “to behave like an Empress” (Dalai Lama XIV, 1993a, p. 267).

In the case of Jiang Qing it is nevertheless not as easy to see her as an incarnation of Guanyin and an opponent of Avalokiteshvara (the Dalai Lama) as it is with Ci Xi, who deliberately took on this divine role. With her Marxist-Leninist orientation, the Communist Jiang Qing can only unconsciously or semiconsciously have become a “vessel” of the Chinese water goddess. Publicly, she projected an atheist image — at least from a western viewpoint. But this fundamentally anti-religious attitude must — more and more historians are coming to agree — be exposed as a pretence. Maoism was — as we shall later discuss at length — a deeply religious, mythic movement, located totally within the tradition of the Chinese Empire. The Dalai Lama’s suspicion that Jiang Qing felt like an Empress is thus correct.

Incidentally, she did so quite consciously, when she openly compared herself to the Empress Wu Zetian, who — as we have shown — tried as a female Buddha to seize control of the world, and who symbolically preempted the ideas of the Kalachakra Tantra in the construction of a time tower. Jiang Qing also wanted to seize the time wheel of history. In accordance with the Chinese predilection for all manner of ancestral traditions, she (the Communist) had clothes made for her in the style of the old Tang ruler (Wu Zetian).

“Jiang Qing, who had previously taken little interest in Chinese history, became an avid student of the career of Wu [Zetian] and the careers of other great women near the throne. Her personal library swelled with books on the subject. Teams of writers from her fanatically loyal faction scurried to prepare articles showing that Empress Wu, until then generally regarded as a lustful, power-hungry shrew, was ‘anti-Confucian’ and hence ‘progressive’. ‘Women can become emperor,’ Jiang would say to her staff members. ‘Even under communism there can be a woman ruler.’ She remarked to Mao’s doctor that England was not as feudal as China because it was ‘often ruled by queens.’“ (Ross, 1999, p. 273) - “Jiang Qing was deeply interested in the ideas and methods of Empress Dowager Ci Xi. But it was impossible for her to praise Ci Xi publicly because ultimately Empress Dowager Ci Xi failed to keep the West at bay and because she was too vivid a part of the ancien régime that the Communist Party had gloriously buried.” (Ross, 1999, p. 27)

But can we conclude from Jiang Qing’s preference for the imperial form of power that she is an incarnation of Guanyin? On the basis of her own view of things, we must probably reject the hypothesis. But if — like the Buddhist Tantrics — we accept that deities represent force fields which can be embodied in people, then such an assumption seems natural. The only question is whether it is in every case necessary that such people deliberately summon the gods or whether it is sufficient when their spirit and energy “inspire” the people in their possession to act. What counts in the final instance for a Tantric is a convincing symbolic interpretation of political events: The mythic competition between China and Tibet, between the Chinese Emperor and the Dalai Lama, between the Empress Wu Zetian and the Tibetan kings, between the Empress Dowager Ci Xi and the Thirteenth Dalai Lama, all give the conflict between the Fourteenth Dalai Lama and Jiang Qing a metapolitical meaning and render it comprehensible within a tantric scheme of things. The parallels between these conflicts are so striking that from an ancient viewpoint they can without further ado be seen as the expression of a primordial, divine scenario, the dispute between Avalokiteshvara and Guanyin over the world throne of the Chakravartin.

Before we in conclusion compare the religious-political role of the three “Empresses” with one another, we would like to once more emphasize that it is not us who see in China a matriarchal power which opposes a patriarchal Tibet. In contrast we plan in the rest of this study to report several times upon Chinese androcentrism. What we nonetheless wish to convey is the fact that from a Lamaist/tantric viewpoint the Chinese-Tibetan conflict is perceived as a battle of the sexes. Tantrism does not just sexualize landscapes, the elements, time, and the entire universe, but likewise politics as well.

From a Chinese (Taoist, Confucian, or Communist) viewpoint this may appear completely different. But we must not overlook that two of the female rulers we have introduced were fanatic (!) Buddhists with tantric (Ci Xi), or proto-tantric (Wu Zetian) ideas. Both will thus have perceived their political relationship to Tibet through Vajrayana spectacles, so to speak.

Wu Zetian let herself be worshipped as an incarnated Buddha and a Buddhist messiah. Her religious-political visions display an astonishing similarity to those of the Kalachakra Tantra, although this was first formulated several centuries later. As Chakravartin she stood in mythically irreconcilable opposition to the Tibetan kings, who, albeit later (in the 17th century), were entitled to the same designation. Admittedly, one cannot speak of her as an incarnation of Guanyin, since the cult of the Chinese goddess first crystallized out of her time. But there are a number of indications that she was the historical individual in whom the transformation of Avalokiteshvara into Guanyin took place. She was — in her own view — the first “living Buddha” in female form, as is likewise true of Guanyin.

Most unmistakably, Guanyin is “incarnated” in Ci Xi, since the Empress Dowager openly announced herself to be an embodiment of the goddess. There are many indications that the Chinese autocrat was deeply familiar with the secrets of Lamaist Tantrism. She must therefore have seen her encounter with the Thirteenth Dalai Lama as an elevated symbolic game for which in the end she had to pay with her life.

With Jiang Qing, the statement that she was an incarnation of Guanyin is no longer so convincing. The fanatical Communist was no follower of Buddha like her two predecessors and maintained an atheist image. But in her “culturally revolutionary” decisions and “proletarian” art rituals, in her contempt for all clergy, she acted and thought like a “raging goddess” who revolted with hate and violence against patriarchal traditions. Her radical nature made her into an avenging Erinnye (or an out-of-control dakini) in a tantric “match of the gods” (as the Tantrics saw history to be). There is no doubt that high-ranking Tibetan lamas interpreted the historical role of Jiang Qing thus. All three “Empresses” failed with their politics and religious system.

Wu Zetian had to officially renounce her title as “Coming Buddha”. After her death, Confucianism regained its power and began a countrywide persecution of the Buddhists.

Ci Xi died during the visit of her “arch-enemy” (the Thirteenth Dalai Lama). Within a few years of her death the reign of the Manchu dynasty was over (1911).

Jiang Qing was condemned to death by her own (Communist) party as a “left deviationist”, and then pardoned. Even before she died (in 1991), the Maoist regime of “the Red Sun” had collapsed once and for all.

Starting once more from a tantric view of things, one can speculate as to whether all three female historical figures (who as incarnations of Guanyin are to be assigned to the element of “water”) had to suffer the fate of a “fire woman”, a Candali. Then in the end, like the Candali, they founder in their own flames (political passion). All three, although staunch opponents of a purely men-oriented Buddhism, deliberately grasped the religious images and methods of the patriarchally organized world. Wu Zetian and Ci Xi let themselves be addressed with a male title as “old Buddha lord”; Jiang Qing drove all feminine, erotic elements out of the Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution and issued the young women of the Red Guard with male uniforms. In light of the three Chinese “Empresses” the thought occurs that an emancipatory women’s movement cannot survive when it seizes and utilizes the androcentric power symbols and attitudes for itself. We turn to a consideration of these thoughts in the chapter which follows.

Once the majority of the high-ranking Tibetan lamas had to flee the Land of Snows from the end of the 1950s and then began to disseminate Tantric Buddhism in the West, they were willingly or unwillingly confronted with modern feminism. This encounter between the women’s movement of the twentieth century and the ancient system of the androcentric monastic culture is not without a certain delicacy. In itself, one would have to presume that here two irreconcilable enemies from way back came together and that now “the fur would fly”. But this unique relation — as we shall soon see — took on a much more complicated form. Yet first we introduce a courageous and self-confident woman from Tibetan history, who formulated a clear and unmistakable rejection of Tantric Buddhism.

Tse Pongza — the challenger of Padmasambhava

Shortly after Padmasambhava (Guru Rinpoche), the founder of Tibetan Buddhism, entered the “Land of Snows”, a remarkable woman became his decisive opponent. It was no lesser figure than Tse Pongza, the principal wife of the Tibetan king, Trisong Detsen (742–803), and the mother of the heir apparent. The ruler had brought the famous vajra master into the country from India in order to weaken the dominant Bon religion and the nobility. With his active assistance the old priesthood (of the Bon) was banished and the cult was suppressed by drastic measures. A proportion of the Bonpo (the followers of Bon) succumbed to the pressure and converted, another division fled the country, some were decapitated and their bodies thrown into the river. Yet during the whole period of persecution Tse Pongza remained a true believer in the traditional rites and tried by all means to drive back the influence of Guru Rinpoche.

To throw a bad light on her steadfastness, later Buddhist historians accused her of acting out of unrequited love, because Padmasambhava had coldly rejected her erotic advances. Whatever the case, the queen turned against the new religion with abhorrence. “Put an end to these sorcerers” — she is supposed to have said — “... If these sort of things spread, the people’s lives will be stolen from them. This is not religion, but something bad!” (Hermanns, 1956, p. 207). The following open and pointed rejection of Tantrism from her has also been preserved:

What one calls a kapala is a human head placed upon a stand; What one calls basuta are spread-out entrails, What one calls a leg trumpet is a human thighbone What one calls the ‘Blessed site of the great field’ is a human skin laid out. What one calls rakta is blood sprinkled upon sacrificial pyramids, What one calls a mandala are shimmering, garish colors, What one calls dancers are people who wear garlands of bones. This is not religion, but rather the evil, which India has taught Tibet.

(Hoffmann, 1956, p. 61)

With great prophetic foresight Tse Pongza announced: “I fear that the royal throne will be lost if we go along with the new religion” (Hoffmann, 1956, p. 58). History proved her right. The reign of the Yarlung dynasty collapsed circa one hundred years after she spoke these words (838) and was replaced by small kingdoms which were in the control of various Lamaist sects. But it was to take another 800 years before the worldly power of the Tibetan kings was combined with the spiritual power of Lamaism in the institution of the Dalai Lama, and a new form of state arose which was able to survive until the present day: the tantric Buddhocracy.

As far as we are aware, Tse Pongza, the courageous challenger of the Guru Rinpoche (Padmasambhava), has not yet been discovered as a precursor by feminism. In contrast, there is not a feminist text about Tibetan Buddhism in which great words are not devoted to the obedient servant of the guru, Yeshe Tsogyal (the contemporary of Tse Pongza and her counterpole). Such writings are also often full of praise for Padmasambhava. This is all the more surprising, because the latter — as the ethnologist and psychoanalyst, Robert A. Paul, has convincingly demonstrated and as we shall come to show in detail — must be regarded as a sexually aggressive, women and life-despising cultural hero.

We can distinguish four groups in the modern western debate among women about tantric/Tibetan Buddhism and Tibetan history:

The supporters, who have unconditionally subjected themselves to the patriarchal monastic system.

The radical feminists, who strictly reject it and unconditionally damn it.

Those women who strive for a fundamental reform so as to attain a partnership with equal rights within the Buddhist doctrine.

The feminists who have penetrated the system so as to make the power methods developed in Tantrism available for themselves and other women, that is, who are pursuing a gynocentric project.

Outside of these groups one individual towers like a monolith and is highly revered and called as a witness by all four: Alexandra David-Neel (1868–1969). At the start of this century and under the most adventurous conditions, the courageous French woman illegally traversed the Tibetan highlands. She was recognized by the Tibetans as a female Lama and — as she herself notes — revered as an incarnation from the “Genghis Khan race”. (quoted by Bishop, 1989, p. 229).

In 1912 she stood before the Thirteenth Dalai Lama as the first western woman to do so. Despite her fascination with Tibet and her in-depth knowledge of the Lamaist culture she never allowed herself to become completely captivated or bewitched. When it appeared there would be a second audience with His Holiness, the Frenchwoman, the daughter of a Calvinist father and a Catholic mother, said : “I don't like popes. I don't like the kind of Buddhist Catholicism over which he presides. Everything about him is affected, he is neither cordial nor kind” (Batchelor, 1994, p. 311).

Alexandra David-Neel had both a critical and an admiring attitude towards Lamaism and the tantric teachings. She was also repulsed by the dirty and degrading conditions under which the people of Tibet had to live, and thus approved of the Chinese invasion of 1951. On the other hand, she was so strongly attracted to Tibetan Buddhism that she proved to be its most eager and ingenious student. We are indebted to her for the keenest insights into the shady side of the Lamaist soul. Today the author, who lived to be over 100, has become a feminist icon.

Let us now take a closer look at the four orientations of women towards Lamaism described above:

1. The supporting group first crystallized out of a reaction to the other three positions mentioned. It has solely one thing in common with a “feminist” stance, namely that it’s proponents dare to speak out in matters of religion, which was very rarely permitted of Tibetan women in earlier times. The group forms so to speak the female peace-keeping force of patriarchal Buddhism. Among its members are authors such as Anne Klein, Carole Divine, Pema Dechen Gorap, and others. Their chief argument against the claim that woman are oppressed in Vajrayana is that the teaching is fundamentally sexually neutral. The Dharma is said to be neither masculine nor feminine, the sexes forms of appearance in an illusionary world. Karma Lekshe Tsomo, a Buddhist nun of western origin, thus reacts to modern radical feminist current with the following words of rejection: “A growing number of women and also some men feel the need to identify enlightenment with a feminine way. I reject the idea that enlightenment can be categorized into gender roles and identified with these at all. ... Why should the awareness be so intensely bound to a form as the genitals are?” (quoted by Herrmann-Pfand, 1992, p. 11). With regard to the social situation of women in the Tibet of old, the authors of the first group proclaim, in comparison with those in other Asian countries they enjoyed the greatest freedoms.

2. The discrimination against the female sex in all historical phases of Buddhism is, however, so apparent that it has given rise to an extensive, in the meantime no longer surveyable, literature of feminist critiques, which very accurately and without holding back unmask and indict the system at all levels. For early Buddhism, it is above all Diana Y. Paul who has produced a sound and significant contribution. Her book, Women in Buddhism, has become a standard work in the meantime.

The sexual abuse of women in the modern Buddhist centers of the West has been made public by, among others, the American, Sandy Boucher. In many of these feminist critiques social arguments — on the one side an androcentric hierarchy, on the other the oppressed woman — are as frequent as theological and philosophical ones.

The points which the neo-shaman and Wicca Witch, Starhawk, brings against the Buddhist theory of suffering seem to us to be of such value that we would like to quote them at length. Starhawk sees herself as a representative of the witch (Wicca) movement, as a feminist dakini: “Witchcraft does not maintain, like the First Truth of Buddhism, that 'all life is suffering'. On the contrary, life is a thing of wonder. The Buddha is said to have gained this insight [about suffering) after his encounter with old age, disease and wealth. In the Craft [i.e., the witch movement], old age is a natural and highly valued part of the cycle of life, the time of greatest wisdom and understanding. Disease, of course, causes misery but it is not something to be inevitably suffered: The practice of the Craft was always connected with the healing arts, with herbalism and midwifery. Nor is death fearful: It is simply the dissolution of the physical form that allows the spirit to prepare for new life. Suffering certainly exists in life — it is part of learning. But escape from the wheel of Birth and Death is not the optimal cure, any more than hara-kiri is the best cure of menstrual cramps.” (quoted by Gross, 1993, p. 284).

This radical feminist critique naturally also extends to Vajrayana: the cynical use of helpless girls in the sexual magic rituals and the exploitation of patriarchal positions of power by the tantric gurus stand at the center of the “patriarchal crimes”. But the alchemic transformation of feminine energy into a masculine one and the “tantric female sacrifice”, both of which we discussed so extensively in the first part of our study, are up until now not a point of contention. We shall soon see why.

3. The authors Tsultrim Allione, Janice Willis, Joana Macy, and Rita M. Gross can be counted among the third “reform party”. The latter of these believes it possible that a new world-encompassing vision can develop out of the encounter between feminism and Buddhism. She thus builds upon the critical work of the radical feminists, but her goal is a “post-patriarchal Buddhism”, that is, the institutionalization of the equality of the sexes within the Buddhist doctrine (Gross, 1993, p. 221). This reform should not be imposed upon the religious system from outside, but rather be carried through in “the heart of traditional Buddhism, its monasteries and educational institutions” (Gross, 1993, p. 241). Rita Gross sees this linkage with women as a millennial project, which is supposed to continue the series of great stages in the history of Buddhism.

For this reason she needs no lesser metaphor to describe her vision than the “turning of the wheel”, in remembrance of Buddha’s first sermon in Benares where, with the pronouncement of the Four Noble Truths, he set the “wheel of the teaching” in motion. If, as is usual in some Buddhist schools, one sees the first turning as the “lesser vehicle” (Hinayana), the second as the “great vehicle” (Mahayana), and the third as Tantrism (Tantrayana), then one could, like Gross, refer to the connection of Buddhism and feminism as the “fourth vehicle” or the fourth turning of the wheel. “And with each turning,” this author says, “we will discover a progressively richer and fuller basis for reconstructing androgynous [!] Buddhism” (Gross, 1993, p. 155). Many of the fundamental Buddhist doctrines about emptiness, about the various energy bodies, about the ten-stage path to enlightenment, about emanation concepts would be retained, but could now also be followed and obeyed by women. But above all the author places weight on the ethical norms of Mahayana Buddhism and gives these a family-oriented twist: compassion with all beings, thus also with women and children, the linking of family structures with the Sangha (Buddhist community), the sacralization of the everyday, male assistance with the housework, and similar ideas which are drawn less from Buddhism as from the moderate wing of the women’s movement.

Like the Italian, Tsultrim Allione, Gross sees it as a further task of hers to seek out forgotten female figures in the history of Buddhism and to reserve a significant place for them in the historiography. She takes texts like the Therigatha, in which women in the Hinayana period already freely and very openly discussed their relationship to the teachings, to be proof of a strong female presence within the early phase of Buddhism. It is not just the lamas who are to blame for the concealment of “enlightened women”, but also above all the western researchers, who hardly bothered about the existence of female adepts.

She sees in Buddhist Tantrism a technique for overcoming the gender polarity, in the form of an equality of rights of course. One can say straight out that she has not understood the alchemic process whereby the feminine energy is sucked up during the tantric ritual. Like the male traditionalists she seizes upon the image of an androgyny (not that of a gynandry), of which she erroneously approves as a “more sexually neutral” state.

4. Fourthly, there are those women who wish to reverse the complex of sexual themes in Buddhism exclusively for their own benefit. The American authors, Lynn Andrews and, above all, Miranda Shaw, can be counted among these. In her book, Passionate Enlightenment — Women in Tantric Buddhism, she speaks openly of a “gynocentric” perspective on Buddhism (Shaw, 1994, p. 71). Shaw thus stands at the forefront of western women who are attempting to transform the tantric doctrine of power into a feminist intellectual edifice. With the same intentions June Campbell subtitles her highly critical book, Traveller in Space, as being “In Search of Female Identity in Tibetan Buddhism”. She too renders tantric practices, which she learned as the pupil of the Kagyu master, Kalu Rinpoche, over many years, useful for the women’s movement. Likewise one can detect in the German Tibetologist, Adelheid Herrmann-Pfand’s study about the dakinis the wish to detect female alternatives within the tantric scheme of things.

But of all of these Miranda Shaw has the most radical approach. We shall therefore concentrate our attention upon her. Anybody who reads her impassioned book must gain the impression that it concerns the codification of a matriarchal religion to rival Vajrayana. All the feminine images which are to be found in Tantrism are reinterpreted as power symbols of the goddess. The result is a comprehensive world view governed by a feminine arch-deity. We may recall that such a matriarchal viewpoint need not differ essentially from that of an androcentric Tantric. He too sees the substance of the world as feminine and believes that the forces which guide the universe are the energies of the goddess. Only in the final instance does the vajra master want to have the last say.

For this reason the “tantric” feminists can without causing the lamas any concern reach into the treasure chest of Vajrayana and bring forth the female deities stored there, from the “Mother of all Buddhas”, the “Highest Wisdom”, the goddess “Tara”, to all conceivable kinds of terror dakinis. These formerly Buddhist female figures — the nurturing and protective mother, the helper in times of need, and the granter of initiations — apparently stand at the center of a new cult. Shaw can rightly draw attention to numerous cases in which women were inducted into the secrets of Tantrism as the dakinis of Maha Siddhas. It was they who equipped their male pupils with magic abilities. Their powers, the legends teach us, vastly exceeded those of the men. The tantra texts are also said to have originally been written by women. The ranks of the 84 official Maha Siddhas (great Tantrics) at any rate include four women, one of whom, Lakshminkara, is considered to be the founder of a teaching tradition of her own. In the more recent history of Vajrayana as well, “enlightened women” crop up again and again: the yoginis Niguma, Yeshe Tshogyal, Ma gcig, and others.

As evidence for the hypothesized power of women in Buddhist Tantrism the feminist side likes to parade the Candamaharosana Tantra with those passages in it in which the man is completely subordinate to the dictates of the woman. But the hymn to the goddess quoted in the following is still no more a sequence in the tantric inversion process, despite its depiction of the servitude of the male lover: as usual, in this case too it is not the female deity but rather the central male who is the victor in the guise of a guru. Here are the words, which the goddess addresses to her partner:

Place my feet upon your shoulders and Look me up and down Make the fully awakened scepter (Phallus) Enter the opening in the center of the lotus (Vagina) Move a hundred, thousand, hundred thousand times in my three-petaled lotus of swollen flesh.

(Shaw, 1994, pp. 155-156)

Shaw comments upon this erotic poem with the following revealing sentences: “The passage reflects what can be called a 'female gaze' or gynocentric perspective, for it describes embodiment and erotic experience from a female point of view. ... [The man] is instructed not to end the worship until the woman is fully satisfied. Only then is he allowed to pause to revive himself with food and wine — after serving the woman and letting her eat first, of course! Selfish pleasure-seeking is out of the question for him, for he must serve and please his goddess” (Shaw, 1994, p. 156). But the tantra is in fact dedicated to a wrathful and extremely violent male deity and differs from other texts solely in that the adept has set himself the difficult exercise of being completely sexually subordinate to the woman so as to then — in accordance with “law of inversion” — be able to celebrate an even greater victory over the feminine and his own passions. The woman’s role as dominatrix, which Shaw proudly cites, must also be seen as an ephemeral moment along the masculine way to enlightenment.

Yet Miranda Shaw sees things differently. For her it was women who invented and introduced Tantrism. They had always been the bearers of secrets. Thus nothing in the tantras must be changed in the coming “age of gynandry” other than that the texts once more lay the foundations for the supremacy of the woman, so that she can take up her former tantric post as teacher and grasp anew the helm which had slipped from her hands. From now on the man has to obey once more: “Tantric texts “, Shaw says, “specify what a man has to do to appeal to, please and merit the attention of a woman, but there are no corresponding requirements that a woman must fulfill” (Shaw, 1994, p. 70). At another point we may read that, “the woman may also see her male partner as a deity in certain ritual contexts, but his divinity does not carry the same symbolic weight. She is not required to respond to his divinity with any special deference, respect, or supplication or to render him service in the same way that he is required to serve her.” (Shaw, 1994, p. 47). In place of the absolute god, the absolute goddess now strides across the cosmic stage alone and seizes the long sought scepter of world dominion.

Such feminist rapprochements with Vajrayana Buddhism, however, prove on closer inspection to walk right into a well-disguised tantric trap. Precisely in the moment where the modern emancipated woman believes she has freed herself from the chains of the patriarchal system, she becomes without noticing even more deeply entangled in it. This effect is caused by the tantric “law of inversion”. As we know, within the logic of this law, the yogini must be elevated to a goddess before her defeat and domination at the hands of the guru, and the vajra master is under no circumstances permitted to recoil if she comes at him in a furious and aggressive form. In contrast, he is — if he takes the “law of inversion” seriously — downright obliged to “set fire to” the feminine, or better, to bring it to explosion. The hysterical terror dakinis of the rituals are just one of the indicators of the “inflaming” of female emotions during the initiations. In our analysis of the feminine inner fire (the Candali) as a further example, we showed how the “fire woman” ignited by the yogi stands in radical confrontation to him who has set fire to her, since she is supposed to burn up all of his bodily aggregates. On the astral plane the tantra master likewise uses the feminine “apocalyptic fire” (Kalagni) to reduce the cosmos to smoking rubble. The aggressively feminine, which can find its social expression in the form of radical gynocentric feminism, is thus a part of the tantric project. Who better represents a flaming, wrathful, dangerous goddess than a feminist, who furiously turns upon the fundamental principles of the teaching (the Dharma)?

If we consider the feminist craving for fire as an element of power in the work of such a prominent figure as the American cultural researcher Mary Daly, then the question arises whether such radical women have not been outwitted by the Tibetan yogis into doing their work for them. Daly even demands a “pyrogenetic ecstasy” for the new woman and calls out to her comrades: "Raging, Racing, we take on the task of Pyrognomic Naming of Virtues. Thus lightning, igniting the Fires of Impassioned Virtues, we sear, scorch, singe, char, burn away the demonic tidy ties that hold us down in the Domesticated State, releasing our own Daimons/Muses/Tidal Forces of creation ... Volcanic powers are unplugged, venting Earth’s Fury and ours, hurling forth Life-lust, like lava, reviving the wasteland, the World” (Daly, 1984, p. 226). Such an attitude fits perfectly with the patriarchal strategy of a fiery destruction of the world such as we find in the Buddhist Kalachakra Tantra and likewise in the Christian Book of Revelations. In their blind urge for power, the “pyromaniac” feminists also set Mother Earth, whom they claim to rescue, on fire. In so doing they carry out the apocalyptic task of the mythic Indian doomsday mare, from whose nostrils the apocalyptic fire (Kalagni) streams and who rises up out of the depths of the oceans. They are thus unwilling chess pieces in the cosmic game of the ADI BUDDHA to come.

Let us recall Giordano Bruno’s statements about one of the fundamental features of a manipulator: the easiest person to manipulate is the one who believes he is acting in his own egomaniac interests, whilst he is in fact the instrument of a magician and is fulfilling the wishes of the latter. This is the “trick” (upaya) with which the yogi dazzles the fearsome feminine, the “evil mother”, and the dark Kali. The more they gnash their razor-sharp teeth, the more attractive they become for the tantra master. According to the “law of inversion” they play out a necessary dramaturgical scene on the tantric stage. As magic directors, the patriarchal yogis are not only prepared for an attack by radical feminism, but have also made it an element in their own androcentric development. Perhaps this is the reason why Miranda Shaw was allowed to conduct her studies in Dharamsala with the explicit permission of the Dalai Lama.

There are internal and external reasons for this unconscious but effective self-destruction of radical feminism. Externally, we can see how in contest with patriarchy they grasp the element of fire, which is also seen as a synonym of the term “power” by the followers of the great goddess. The element of water as the feminine counterpart to masculine fire plays a completely subordinate role in Daly’s and Shaw’s visions. Thus the force under which the earth already suffers is multiplied by the fiery rage of these women. Avalokiteshvara and Kalachakra are — as we have shown — fire deities, i.e., they feed upon fire even if or even precisely because it is lit by “burning” women.

The internal reason for the feminist self-destruction lies in the unthinking adoption of tantric physiology by the women. If such women practice a form of yoga, along the lines Miranda Shaw recommends, then they make use of exactly the same techniques as the men, and presume that the same energy conditions apply in their bodies. They thus begin — as we have already indicated — to destroy their female bodies and to replace it with a masculine structure. This is in complete accord with the Buddhist doctrine. Thanks to the androcentric rituals her femininity is dissolved and she becomes in energy terms a man.

Between March 30 and April 2, 2000, representatives from groups three and four convened in Cologne, Germany at a women-only conference. Probably without giving the matter much thought, the Buddhist journal Ursache & Wirkung (Cause and Effect) ran its report on the meeting at which 1200 female Buddhists participated under the title of “Göttinnen Dämmerung” [Twilight of the Goddesses) — which with its reference to the götterdämmerung signified the extinction of the goddesses (Ursache & Wirkung, No. 32, 2/2000).

Now whether the yogis can actually and permanently maintain control over the women through their “tricks” (upaya) is another question. This is solely dependent upon their magical abilities, over which we do not wish to pass judgment here. The texts do repeatedly warn of the great danger of their experiments. There is the ever-present possibility that the “daughters of Mara” see through the tricky system and plunge the lamas into hell. Srinmo, the fettered earth mother, may free herself one day and cruelly revenge herself upon her tormentors, then she too has meanwhile become a central symbol of the gynocentric movement. Her liberation is part of the feminist agenda. "One senses a certain pride”, we can read in the work of Janet Gyatso, "in the description of the presence of the massive demoness. She reminds Tibetans of fierce and savage roots in their past. She also has much to say to the Tibetan female, notably more assertive than some of her Asian neighbours, with an independent identity, and a formidable one at that. So formidable that the masculine power structure of Tibetan myth had to go to great lengths to keep the female presence under control. […. Srinmo) may have been pinned and rendered motionless, but she threatens to break loose at any relaxing of vigilance or deterioration of civilization” (Janet Gyatso, 1989, p. 50, 51).

The Fourteenth Dalai Lama and the question of women's rights

The relationship of the Fourteenth Dalai Lama to the female sex appears sincere, positive, and uninhibited. Leaving the tantric goddesses aside, we must distinguish between three categories of women in his proximity: 1. Buddhist nuns; 2.Tibetan women in exile; 3. Western lay women.

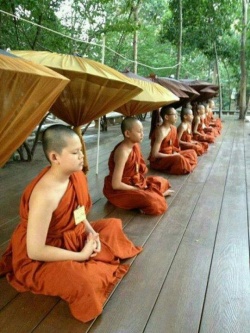

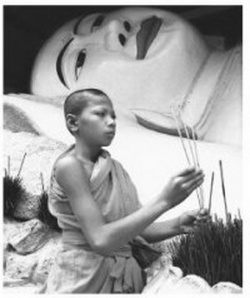

At the outset of our study we described the extremely misogynist feelings Buddha Shakyamuni exhibited towards ordained female Buddhists. In a completely different mood, the Fourteenth Dalai Lama succeeded in becoming a figure of hope for all the women assembled at the first international conference of Buddhist nuns in 1987 in Bodh Gaya (India). It was the Kundun and not a nun (bhiksuni) who launched proceedings with his principal speech. It surely had a deep symbolic/tantric significance for him that he held his lecture inside the local Kalachakra temple. There, in the holiest of holies of the time god, the rest of the nuns’ events also took place, beginning each time with a group meditation. It is further noteworthy that it was not just representatives of Tibetan Buddhism who turned to the god-king as the advocate of their rights at the conference but also the nuns of other Buddhist schools. [8]

In his speech the Kundun welcomed the women’s initiative. First up, he spoke of the high moral and emotional significance of the mother for human society. He then implied that according to the basic principles of Mahayana Buddhism, no distinction between the sexes may be made and that in Tantrayana the woman must be accorded great respect. The only sentence in which the Kundun mentioned Tantrism in his speech was the following: “It is for example considered an infringement when tantra practitioners do not bow down before women or step around them during their accustomed practice of the yoga [in their meditations)" (Lekshe Tsomo, 1991, p. 34). The Buddhist women present would hardly have known anything about real women (karma mudras) who participate in the sexual magic practices, about the ceremonial elevation of the woman by the lama so as to subsequently absorb her gynergy, or about the “tantric female sacrifice”.

The Dalai Lama continued his speech by stressing the existence of several historical yoginis in the Indian and Tibetan traditions in order to prove that Buddhism has always offered women an equal chance. In conclusion he drew attention to the fact that the negative relationship to the female sex which could be found in so many Buddhist texts are solely socially conditioned.

When the decisive demand was then aired, that women within the Buddhist sects be initiated as line-holders so that they would as female gurus be entitled to initiate male and female pupils, the Kundun indicated with regret that such a bhiksuni tradition does not exist in Tibet. However, as it can be found in China (Hong Kong and Taiwan), it would make sense to translate the rules of those orders and to distribute them among the Tibetan nuns. In answer to the question — “Would they [then] be officially recognized as bhiksunis [[[Wikipedia:female|female]] teachers)?” — he replied evasively — “Primarily, religious practice depends upon one’s own initiative. It is a personal matter. Now whether the full ordination were officially recognized or not, a kind of social recognition would at any rate be present in the community, which is extremely important” (Lekshe Tsoma, 1991, p. 246). But he himself could not found such a tradition, since he saw himself bound to the traditional principles of his orders (the Mulasarvastivada school) which forbade this, but he would do his best and support a meeting of various schools in order to discuss the bhiksuni question. Ten years later, in Taiwan, where the “Chinese system” is widespread, there had indeed been no concrete advances but the Kundun once again had the most progressive statement ready: “I hope”, he said to his listeners, “that all sects will discuss it [the topic] and reach consensus to thoroughly pass down this tradition. For men and women are equal and can both accept Buddha's teachings on an equal basis.” (Tibetan Review, May 1997, p. 13).

Big words — then the reformation of the repressive tradition of nuns dictated to by men is fiercely contested within Lamaism. But even if in future the bhiksunis are permitted to conduct rituals and are recognized as teachers in line with the Chinese model, this in no way affects the tantric rites, which do not even exist within the Chinese system and which downright celebrate the discrimination against women as a cultic mystery.

Tibetan women in exile

As far as their social and political position is concerned, much has certainly changed for the Tibetan women in exile in the last 35 years. For example, they now have the right to vote and to stand as a candidate. Nonetheless, complaints about traditional mechanisms of suppression in the families are a major topic, which thanks to the support of western campaigners for women’s rights do not seldom reach a wider public. Nonetheless, here too the Kundun plays the reformer and we earnestly believe that he is completely serious about this, then he has had for many years been able to experience the dedication, skillfulness, and courage of many women acting for his concerns. All Tibetan women in exile are encouraged by the Kundun to participate in the business of state. The Tibetan Women's Association, extremely active in pursuing societal interests, was also founded with his support.

Despite these outwardly favorable conditions, progress towards emancipation has been very slow. For example, the three permanent seats reserved for women in the parliament in exile could not be filled for a long period, simply because there were no candidates. (There are 130,000 Tibetans living in exile.) This has improved somewhat in the meantime. In 1990 the Kundun induced his sister, Jetsun Pema, to be the first woman to take up an important office in government. In 1996 eight women were elected to the public assembly.

Sometimes, under the influence of the western feminism, the question of women’s rights flares up fiercely within the exile Tibetan community. But such eruptions can again and again be successfully cut off and brought to nothing through two arguments:

1. The question of women’s rights is of secondary nature and disrupts the national front against the Chinese which must be maintained at all costs. Hence, the question of women’s rights is a topic which will only become current once Tibet has been freed from the Chinese yoke.

2. The chief duty of the women in exile is to guarantee the survival of the Tibetan race (which is threatened by extinction) through the production of children.

The Kundun’s encounters with western feminism

In the West the Dalai Lama is constantly confronted with emancipation topics, particularly since no few female Buddhists originally hailed from the feminist camp or later — the wave has just begun — migrated to it. As in every area of modern life, here too the god-king presents an image of the open-minded man of the world, liberal and in recent times even verbally revolutionary. In 1993, as critical voices accusing several lamas of uninhibited excessive and degrading sexual behavior grew louder, he took things seriously and promised that all cases would be properly investigated. In the same year, a group of two dozen western teachers under the leadership of Jack Kornfield met and spoke with His Holiness about the meanwhile increasingly precarious topic of “sexual abuse by Tibetan gurus”. The Kundun told the Americans to “always let the people know when things go wrong. Get it in the newspapers themselves if needs be” (Lattin, Newsgroup 17).

In 1983, at a congress in Alpach, Austria, His Holiness came under strong feminist fire and was attacked by the women present. One of the participants completely overtaxed him with the statement that, “I am very surprised that there is no woman on the stage today, and I would have been very glad to see at least one woman sitting up there, and I have the feeling that the reason why there are no female Dalai Lamas is simply that they are not offered enough room” (Kakuska, 1984, p. 61). Another participant at the same meeting abused him for the same reasons as “Dalai Lama, His Phoniness!” (Kakuska, 1984, p. 60).

The Kundun learned quickly from such confrontations, of which there were certainly a few in the early eighties. In an interview in 1996, for example, he described with a grin the goddess Tara as the “first feminist of Buddhism” (Dalai Lama XIV, 1996b, p. 76). In answer to the question as to why Shakyamuni was so disdainful of women, he replied: "2500 years ago when Buddha lived in India he gave preference to men. Had he lived today in Europe as a blonde male he would have perhaps given his preference to women” (Tibetan Review, March 1988, p. 17). His Holiness now even goes so far as to believe it possible that a future Dalai Lama could be incarnated in the form of a woman. “In theory there is nothing against it” (Tricycle, 1995, V (1), p. 39; see also Dalai Lama XIV, 1996b, p. 99). In 1997 he even enigmatically prophesied that he would soon appear in a female form: “The next Dalai Lama could also be a girl” (Tagesanzeiger, June 27, 1995).

According to our analysis of Tantrism, we must regard such charming flattery of the female sex as at the very least a non-committal, albeit extremely lucrative embellishment. But they are more likely to be a deliberately employed manipulation, so as to draw attention away from the monstrosities of the tantric ritual system. Perhaps they are themselves a method (upaya) with which to appropriate the “gynergy” of the women so charmed. After all, something like that need not only take place through the sexual act. There are descriptions in the lower tantras of how the yogi can obtain the feminine “elixir” even through a smile, an erotic look or a tender touch alone.

It has struck many who have attended a teaching by the Dalai Lama that he keeps a constant and charming eye contact with women from the audience, and is in fact discussed in the Internet: “Now it is quite possible”, Richard P. Hayes writes there regarding the “flirts” of the Kundun, “that he was making a fully conscious effort to make eye-contact with women to build up their self-esteem and sense of self-worth out of a compassionate response to the ego crushing situations that women usually face in the world. It is equally possible that he was unconsciously seeking out women's faces because he finds them attractive. And it could well be that he finds women attractive because they trigger his Anima complex in some way” (Hayes, Newsgroup 11). Hayes is right in his final sentence when he equates the female anima with the tantric maha mudra (the “inner woman”). With his flirts the Kundun enchants the women and at the same time drinks their “gynergy”.

The role of women in the sacred center of Tibetan Buddhism can only change if there were to be a fundamental rejection of the tantric mysteries, but to date we have not found the slightest indication that the Kundun wants to terminate in any manner his androcentric tradition which at heart consists in the sacrifice of the feminine.

Nevertheless, he amazingly succeeds in awakening the impression — even among critical feminists — that he is essentially a reformer, willing and open to modern emancipatory influences. It seems the promised changes have only not come about because, as the victim of a traditional environment, his hands are tied (Gross, 1993, p. 35). This pious wishful notion proves nothing more than the fascination that the great “manipulator of erotic love” from the “roof of the world” exercises over his female public. His charming magic in the meantime enables him to enthuse and activate a whole army of women for his Tibetan politics in the most varied nations of the world.

The “Ganachakra” of Hollywood

Relaxed and carefree, with a certain spiritual sex appeal, the Kundun enjoys all his encounters with western women. As the world press confirms, the “modest monk” from Dharamsala counts as one of the greatest charmers among the current crop of politicians and religious leaders. "Any woman”, Hicks and Chogyam write in their biography of the Dalai Lama, "who has had been fortunate enough to be granted an audience will tell you what a charming host he is” (Hicks and Chogyam, 1990, p. 66). But Alexandra David-Neel had a completely different opinion of his previous incarnation, the Thirteenth Dalai Lama, whom she described as stiff, obsessed by power, and heartless.

Just as a major film star is surrounded by enthusiastic fans, so too the Dalai Lama — at a higher level — attracts a crowd of enthusiastic male and female film stars. The proportion of world-famous actresses and singers in his “retinue” has notably increased in the meantime, and among them are to be found many of the most well-known faces: Sharon Stone, Anja Kruse, Uma Thurman, Christine Kaufmann, Sophie Marceau, Tina Turner, Doris Dörrie, Koo Stark, Goldie Hawn, Meg Ryan, Shirley MacLaine and a number of others count among them. “Even Madonna has ‘come out’ spiritually”, the Spiegel reflects, “The 'Material Girl' soon possibly a Tibet sister?” (Spiegel, 16/1998, p. 109). “In Hollywood the leader of Tibet is currently revered like a god”, writes Playboy (Playboy (German edition], March 1998, p. 44).

But what motivates these international celebrities to join the Kundun and his tantric Buddhist teachings with such enthusiasm? We shall speak later about the male stars who are followers in particular, and thus in this section cast a glance at the famous women who have adopted the Buddhist faith in recent years. Bunte, a high-circulation German magazine, has attempted to identify the female stars’ motives for their change of faith. Alongside the usual descriptions of peace, calm, and quiet, we can also read the following:

"More and more women are turning to Buddhism, both in Europe and America. And when you look at them, you might think: hello, looks like she’s had a facelift? — No, it’s the teaching of Buddha which is making her desirable and attractive. Buddhism ... gives them peace — and peace is the basis of the harmony from which alone erotic love can grow. ... In the great religions of the world people, in particular women, are constantly under siege: from commandments, bans, taboos, guilt complexes and mystic visions of purgatory, Judgment Day, and hell. But Buddhism does not threaten, does not punish, does not damn. ... And then — the “boss”: Buddha is no invisible, punitive, wrathful or even loving god. He is a visible person ... a person, who has found his way and is therefore constantly smiling in likenesses of him. But you don’t have to pray to him — you’re supposed to follow him. For women, Buddha is not the omnipotent patriarch in heaven, but rather a living guru [!]. This makes him especially appealing to women. In Buddhism women do not have to deny their sensuality”. Goldie Hawn, Hollywood sex comedian, rapturously claims, “I meditate and I feel sexy, I am sexy”. Anja Kruse, a German film star, enthuses that through Buddhism she has “gained more positive energy and erotic radiance”. The singer Laurie Andersen believes “Buddhism is so antiauthoritarian that it is attractive”. The actress Shirley MacLaine knows that “You learn that you are also god” (all quotations are from Bunte, no. 46, November 6, 1997, pp. 20ff.).

The manipulation of the feminine sense of the erotic can hardly be better demonstrated than through such articles. Here, the whole misogynist history of Buddhism is transformed into its precise opposite with a few snappy words. This is only one of the deceptions, however. The other is the fact that according to such statements Buddhism holds the dolce vita of the “rich and the beautiful” to be an elevated “spiritual” goal. “For Christians and Moslems”, it says further in Bunte, “paradise beckons from the beyond. Celebrities already have it on earth — completely in accord with the beliefs of Buddhism” (Bunte, no. 46, November 6, 1997, p. 22). The historical Buddha’s rejection of the comforts of life — an important dogma for his salvational way — is turned into its blatant opposite here: Buddhism, the stars would like us to believe, means luxury and complete independence.

This is deliberate and very successful manipulation. The western press is certainly not responsible for this alone. In that the Tibetan lamas further intensify the egocentricity and the secret wishes of the celebrity women and guarantee their fulfillment through Buddhism, they bring them under their control with a similar method (upaya = trick) to that with which they elevate the karma mudras (real women) to goddesses in their tantric rituals. Who as woman would not reach out for the offers which are promised them, according to Bunte, by the monks in orange robes: “Buddhism is eternal life. If one is lucky, eternal youth as well” (Bunte, no. 46, November 6, 1997, p. 22).

In light of the hells, the taboos, the day of judgment, the homelessness, the apocalyptic battle, the absolute obedience, the unconditional worship of the gurus, the patriarchal authority, the disdain for women and for life and much more of the like, with which the “true” doctrine is traditionally weighed down, the temptations offered by Bunte magazine are purely illusory, especially when we consider the harsh discipline and the strictness which must be borne in the Buddhist lamaseries. Perhaps one of the most famous Buddha legends has now been reversed: A future Buddha who wishes to attain enlightenment will no longer be tempted by the “daughters of Mara” (the daughters of the devil), rather, the “daughters of Mara” (the female stars of Hollywood) who are prepared to step out along the path to enlightenment are tempted by Buddha (the Dalai Lama). It only remains to hope that they like the historical Shakyamuni succeed in seeing through the sweet and charming “devil ghost” of the “sincere” and smiling Kundun.

If we adopt a tantric viewpoint then we may not rule out that all these famous women have in a most sublime manner been made a part of the worldwide Kalachakra project by the lamas. They form — if we may exaggerate slightly — a kind of symbolic ganachakra which is supposed to support the apotheosis of the Dalai Lamas (Avalokiteshvara) into the ADI BUDDHA. With the example of the pop singer Patty Smith we would like to demonstrate how finely and “cleverly” feminine energies can be steered by the Kundun in the meantime.

Patty Smith and the Dalai Lama

Already anticonventional to the point of radicalism in her youth, a great fan of the poètes maudits — Arthur Rimbaud, Frederico Garcia Lorca, Jean Genet, William S. Burroughs and others, Patty Smith grew up in the Factory of Andy Warhol, where she learned her “antiauthoritarian” attitude to life. Anarchist and libertarian, she built a career upon a repertoire which opposed every social norm. Outside of society is where I want to be is the name of one of her most famous pieces. In the eighties her spouse and several of her closest friends died suddenly, which affected her deeply. In order to overcome her pain she turned to Tibetan Buddhism. She remembered having wept and prayed as a twelve-year-old girl at the fate of the Dalai Lama. But she first met the god-king in September 1995 in Berlin and was spellbound: “"I learned quite a bit from that man”, she later said, “he had to be constantly putting things into balance” (Shambhala Sun, July 1996).

The antiauthoritarian Patty Smith had met her master. In the face of the smiling Kundun she would hardly have thought that she had before her a pontiff whose history, ideology and visions opposed all of her libertarian and anarchic freedoms as their exact opposite. No — like a compliant mudra this social rebel bowed to the omnipotent tantra master, without asking where he came from, who he is, or where he is headed. In a poem she wrote about His Holiness she shows how unconditionally she as a woman submits to the divine guru and coming ADI BUDDHA. It opens with the lines

May I be nothing but the peeling of a lotus papering the distance for You underfoot

In this poem the entire sexual magic dramaturgy of Tantrism is played out in an extremely fine way. “Peeling” can suggest “peeling off” in the sense of “stripping naked so as to make love”. The “lotus” is a well-known symbol for the “vagina”. Underfoot also connotes being “under (his) control”. Patty Smith, the social rebel and poet of freedom has become an obedient dakini of the Tibetan god-king.

All these beautiful singers and actresses have forgotten or never even known about the heart of their nailed down sister, Srinmo, which still bleeds beneath the Jokhang (the sacred center of Tibetan Buddhism). The lamentations of the Tibetan earth mother, waiting to be rescued and freed from the daggers which nail her down, do not reach the ears of the unknowing film stars. Also forgotten are all the anonymous girls who over the course of centuries have had to surrender their feminine energies to the tantric clergy, so that the latter could construct its powerful Buddhocracy. Palden Lhamo, who still rides through a sea of boiling blood, driven by the terrible trauma of having murdered her son, is forgotten. The apocalyptic future which threatens us all if we follow the way to Shambhala is forgotten. These women — as many say of them — believe they have escaped the Christian churches and the “white pontiff” but have run directly into the net (in Sanskrit: tantra) of the “yellow pontiff”.

_______________

Footnotes:

[1] A terrible sister of the Palden Lhamo is the goddess Ekajati, the “Protector of the Mantra”. One-eyed and with only one tooth she dances on bodies covered in scratches, swinging a human corpse in one hand, and placing a human heart in her mouth with the other. As adornment she wears a chain of skulls. She is a kind of war goddess and is thus also worshipped under the name of “Magic Weapon Army”.

[2] But Tara like all Tibetan Buddhas and Bodhisattvas also has her terrible side. If this breaks out, she is known as the red Kurukulla, who dances upon corpses and holds aloft various weapons. A rosary of human bones hangs around her neck, a tiger skin covers her hips. In this form she is often surrounded by several wild dakinis. She is invoked in her cruel form to among other things destroy political opponents.