THE THREE VEHICLES OF BUDDHIST PRACTICE

THE THREE VEHICLES OF BUDDHIST PRACTICE

by The Venerable Thrangu Rinpoche Geshe Lharampa

Translated by Ken Holmes

The technical words are italicized the first time they are used to alert the reader that their definition can be found in the Glossary.

Tibetan words (which contain numerous silent letters) are given as they are roughly pronounced, not spelled. For their exact spelling please see the Glossary of Tibetan Terms.

We use the convention of B.C.E. (Before Current Era) for B.C.. and C.E. (Current Era) for A.D. Table of Contents

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the persons who helped make this book possible. First of all, we would like to thank Ken Holmes for translating this work. We would also like to thank Gaby Hollmann for transcribing the tapes and Jean Johnson and Dr. Alta Brown for editing the manuscript. We would also like to thank Tom Leeser for the cover design. The cover photo is of Thrangu Rinpoche’s Vajra Vidya monastery in Sarnath, India. The three calligraphies by Thrangu Rinpoche were made specifically for this book.

Foreword

In the 1970s when a non-scholar was curious about Buddhism, there were only about a dozen books on Buddhism readily available. Then over the next twenty years the West began to invite masters from the East who had actually practiced and studied Buddhist meditation and this changed the number and quality of books on this subject. What emerged from inviting actual practitioners in Buddhism to the West was the understanding that Buddhism was a vast and diverse subject. While Christianity was based on teachings

given in the last few years of the life of Christ, the Buddhist teachings consisted of almost fifty years of teachings of the Buddha filling over forty volumes. What was also surprising was that while the Buddha was an Indian and taught all over Northern India with his teachings becoming vastly important in Indian culture, by the 14th century of our era Buddhism had virtually disappeared from India. Not only had Buddhism left India to the surrounding countries, but all the extensive Buddhist teachings

which had been written down since the first century C.E. were almost completely destroyed in India. The Buddhist teachings both in the original Sanskrit and translated into other languages existed almost exclusively outside India. It was these historical conditions that lead to thinking about Buddhism as having three vehicles which, of course, is the topic of this book. The first migration of Buddhist teachings occurred about 200 years after the Buddha had passed away. The brother of the famous Buddhist

emperor Ashoka took the teachings to the island of Shri Lanka and these teachings were written down in the first century of our era in Pali. These teachings became the basis of what we now call the Theravada school and these - vii - The Three Vehicles of Buddhist Practice teachings spread primarily to the “southern” lands of Thailand, Burma, Cambodia, and Vietnam. Because these teachings were taken to Sri Lanka so early, they are considered to be the earliest teachings of the Buddha. In the third century C.E. a new

movement occurred in which many Buddhist shifted their attention from the Vinaya, which concerned the strict discipline of monks and nuns and the Four Noble Truths towards the teachings of the Buddha on compassion and helping others. This shift was not the creation of a new Buddhism as some have suggested because the Vinaya was still strictly observed and Buddhist teachers even to this day often begin with the Four Noble Truths as the foundation of their teachings. Rather it was more like the establishing of

monasteries and nunneries and the setting up of the rules governing these had been established in the first centuries of Buddhism and now it was time to reach out to others which had always been an important aspect of the Buddha’s teachings. This movement lead to the Mahayana or the second vehicle of Buddhist teachings. A few centuries of elaborating the Mahayana teachings lead to an extraordinary movement called the Madhyamaka school. This school was founded by Nagarjuna and was located in Northern India and

used the scholarly language of the time—Sanskrit. To greatly simplify, up to this time the Buddhist scholars had been building up the Abhidharma teachings which classified all the concepts and ideas of Buddhism. For example, mind was classified into over 100 factors and each of these were classified into wholesome, unwholesome, and neutral states of mind. Furthermore, the followers of the Abhidharma relied heavily on the teachings of the Buddha which taught that the outside world, or phenomena as it is called in

this text, was solid and real, while ideas and thoughts in the mind were impermanent and not real. The Madhyamaka school using teachings of the Buddha not emphasized by the Theravada school were able to show that not only was the mind not solid and “empty,” but also all of

external phenomena was empty as well. Thrangu Rinpoche has said that even when he was learning Buddhism from a great Buddhist master, he had doubts about the emptiness of phenomena. However, with careful study and meditation on this topic, he was convinced and presents some of the most lucid teachings on this subject. In summary, the Mahayana school emphasized compassion and helping

others and the importance of understanding emptiness to achieve enlightenment. To do any work on the Mahayana path one must begin with the accumulation of merit and wisdom and adhere to strict conduct both of which are part of the Theravada level of Buddhism. The development of the Mahayana level of teachings led to the establishment of great monastic universities such as Nalanda University which contained over 10,000 students and teachers. Here philosophical views of followers of various Hindu traditions,

followers of the Theravada, and followers of the Mahayana studied and debated with each other. Outside these scholarly institutions there was another type of Buddhist practitioner whom we would call a “yogi” today. These practitioners did not put on monastic robes and debate each other on the fine points of Buddhist logic, but lived as villagers, often married with children, and practiced a profound type of Buddhism called tantrism. For example, there was Naropa, a famous scholar who spent his days defeating

non-believers in debates at Nalanda University. Then one day after meeting a dakini he left the university and went in search of Tilopa who was a yogi and then spent the rest of his years in the forests of India and practicing tantric Buddhism until he eventually reached enlightenment. The Theravada teachings of the Vinaya along with the Mahayana teachings of compassion and emptiness were carried to the “northern” countries of Pakistan, China, Japan, and Korea. All these teachings and also the Buddhist tantric practices were carried to Tibet in a series of waves that lasted from the 8th century until the 12th century. After the 12th - ix - The Three Vehicles of Buddhist Practice century, there was a Moslem invasion of India in which all the Buddhist colleges and monasteries were destroyed, and almost all of the Buddhist writings were obliterated in India. When early Western scholars first studied Buddhism, they immediately jumped to the conclusion that the Theravada teachings, because they left India

first were the “true Buddhist teachings,” and that the Mahayana teachings, which came later were “invented” in Northern India. They furthermore concluded that the Vajrayana teachings because they resembled Indian tantrism were a “degenerated” form of Buddhism. Many arguments can be advanced to refute these early views.

However, nowadays it seems ridiculous to say that a Zen Buddhist practitioner was practicing an “invented” Buddhism or that the

Dalai Lama who practices the Vajrayana is practicing a “degenerated” form of Buddhism. In 1969 Thrangu Rinpoche was invited to the West and began a series of yearly visits to Samye Ling in Scotland where he shared his vast knowledge with Western students. He first taught the Uttaratantra and the Jewel Ornament of Liberation.

Interspersed with commentaries on these ancient works, he also gave teachings on dharma topics to the Western students. This book, the Three Vehicles of Buddhist Practice or The Three Yanas, was one of these teachings. The Three Vehicles of Buddhist Practice takes the reader through the levels of practice—all of which are essential to master if one is to achieve enlightenment. The Theravada level of teachings explain in detail the Four Noble Truths and the foundational methods of meditation practices. Thrangu Rinpoche has told his students that they should not in any way consider the Theravada teachings a lower or inferior path.

Rather it is more like the lower rungs in a ladder, you cannot reach the top without using them. Rinpoche then describes the path of the bodhisattva—that Buddhist practitioner who has vowed to help all beings reach enlightenment before he or she reaches enlightenment. Here Thrangu Rinpoche gives a very

clear and lucid account of that hard-to-define topic of “emptiness” and “non-self.” Finally, Thrangu Rinpoche gives a clear account of what is perhaps the most misunderstood level of Buddhist practice— the Vajrayana. Being an accomplished Vajrayana practitioner, he is able to describe this level in experiential terms. Throughout this book Thrangu Rinpoche points out that all three of the vehicles of practice were practiced and preserved in Tibet. These levels are just three different ways that the Buddha explained the path to enlightenment. The level a reader actually takes depends entirely on his or her own needs, inclinations, and capabilities.

The Three Vehicles of Buddhist Practice

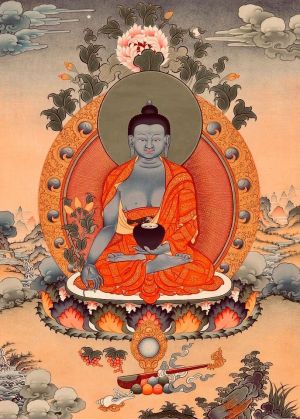

The Buddha in the “touching the earth” position. When the Buddha reached enlightenment, after meditating under the bodhi tree for six weeks, and was asked how he knew he was enlightened, he touched the earth and said, “As the earth is my witness.” The First Vehicle of Buddhist Practice The Theravada Path The Three Vehicles of Buddhist Practice

Thegpa chungngu (Hinayana) by Thrangu Rinpoche

Some say Tibetan Buddhism is the practice of Maha-yana1 Buddhism. Others say that Tibetan Buddhism is actually the practice of Vajrayana Buddhism. Really one cannot say that Tibetan Buddhism is just Mahayana or just Vajrayana Buddhism. The teachings of dharma in Tibet are called the “three immutables” or the “three-fold vajra” meaning the dharma of Tibet contains the teachings of the Theravada, of the Mahayana as well as of the Vajrayana. More specifically, Tibetan Buddhism has the outer practice of the

Theravada, the inner motivation or bodhichitta of the Mahayana, and the view and practice of the Vajrayana known as the secret or essential view. This is why it is necessary to study these three main levels or vehicles (Skt. yanas) of Buddhist practice. One needs to understand that when the Buddha taught, he was not teaching as a great scholar who wanted to demonstrate a particular

philosophical point of view or to teach for its own sake. His desire was to present the very essence of the deep and vast teachings of realization. For this reason he gave teachings which matched the abilities of his disciples. All the teachings he gave, some long and some short, were a direct and appropriate response to the development of the disciples who came to listen to him. Of

course, people have very different capacities and different levels of understanding. They also have very different wishes and desires to learn and understand the dharma. If the Buddha had taught only the very essence of his - 1 - The Three Vehicles of Buddhist Practice own understanding of those vast and far-reaching teachings, then apart from a small number of disciples who had

great intelligence and diligence, few people would have ever entered the path. The Buddha taught whatever allowed a person to develop spiritually and progress gradually towards liberation. When we analyze all the Buddha’s teachings, we see that they fall into three main approaches or vehicles. The Buddha’s teachings helped each student in a way appropriate for the level he or she was at. Because of that, one finds that on the conventional level each student received some benefit from what Buddha taught. On the ultimate level, one finds all of the Buddha’s teachings have the same goal.

When one analyzes the Buddha’s teachings on the relative level, one finds that there are three levels. But, when one examines them from the ultimate level, one sees all levels are directed towards the same goal.

The Theravada Path Of the three yanas the first is the Theravada path which is often called the “Hinayana.” “Hinayana” literally

means “lesser vehicle” but this term should in no way be a reproach or be construed to in any way diminish the importance of these teachings. In fact, the teachings of the Hinayana are very important because they suit the capacities and development of a great number of students. If it weren’t for these teachings, which are particularly appropriate for those with limited wisdom or diligence, many persons would never reach the Mahayana path. Without the Theravada teachings there would be no way for

practitioners to enter the dharma because they would not have had a way to enter the Buddhist path. This path is similar to a staircase: the lower step is the first step. This doesn’t mean it is not important or should be ignored because without these essential steps one can never gain access to the upper stories. It should be very clear that this term “lesser”

vehicle is in no way a pejorative term. It provides the necessary foundation on which to build. The fundamental teachings of the Theravada are the main subject matter of the first turning of the wheel of dharma.

These teachings were given mainly in India in the town of Sarnath which is near the Indian city of Varanasi which is also called Benares. The main subject matter of these teachings were the Four Noble Truths.

The Four Noble Truths If the Buddha had taught his disciples principally by demonstrating his miraculous abilities and powers, this would not have been the best way to demonstrate the path to liberation. The best way to help them attain wisdom and liberation was to point out the very truth of things; to point out the way things are. So he taught the Four Noble Truths and the two truths (conventional and ultimate truth).

By seeing the way things really are, the students learned how to eliminate their wrong view and perceive their delusion. By eliminating wrong views and the causes of the delusion automatically the causes of one’s suffering and hardships will be destroyed. This allows one to progressively reach the state of liberation and great wisdom. That is why the Four Noble Truths and the two truths are the essence of the first teachings of the Buddha.

The First Noble Truth The first noble truth is the full understanding of suffering. Of course, in an obvious way, people are aware of suffering and know when they have unpleasant sensations such as hunger, cold, or sickness. But the first noble truth includes awareness of all the ramifications of suffering. It encompasses the very causal nature of suffering. This includes knowledge of the

subtle and the obvious aspects of suffering. The obvious aspect of suffering is immediate pain or difficulty in the moment. - 3 - The Three Vehicles of Buddhist Practice Subtle suffering is more difficult to recognize because it begins with happiness. But by its very nature this happiness must change because it can’t go on forever. Because it must change into suffering, this subtle suffering is the impermanence of pleasure. For example, when I went to Bhutan with His Holiness the Sixteenth Karmapa, I was

invited to the palace of the king of Bhutan. The palace of the king was magnificent, the king’s chambers were beautiful, there were many servants who showed complete respect and obedience. But we found that even though there was so much external beauty, the king himself was suffering a great deal mentally. The king said that he was quite relieved that His Holiness had come and emphasized how much the visit meant to him because of the various difficulties with which he had been troubled. This is the subtle aspect of

suffering. One thinks that a particular situation will give one the most happiness one can ever imagine, but actually, within the situation, there is a tremendous amount of anguish. If one thinks of those who are really fortunate—gods or human beings with a very rich and healthy life—it seems as though they have nothing but happiness. It is hard to understand that the very root, the very fiber of what is taking place is suffering because the situation is subject to change. What is happiness? By its very nature

it can often mean that there will be suffering later on. There is no worldly happiness that lasts for a very long time. Worldly happiness includes an element of change, of built-in suffering. For that reason the first noble truth of the awareness of suffering refers not just to immediate suffering, but also to the subtle elements of suffering. The Buddha taught the truth of suffering because everything that takes place on a worldly level is a form of suffering. If we are suffering but are not aware of it, we

will never have the motivation to eliminate this suffering and will continue to suffer. When we are aware of suffering, we can overcome it. With the more subtle forms of suffering, if we are - 4 - The Theravada Path

happy and become aware that the happiness automatically includes the seed of suffering, then we will be much less inclined to become attached to this happiness. We will then think, “Oh, this seems to be happiness, but it has built-in suffering.” Then we

will want to dissociate from it. The first truth is that we should be aware of the nature of suffering. Once we have a very clear picture of the nature of suffering, we can really begin to avoid such suffering. Of course, everyone wants to avoid suffering and to emerge from suffering, but to accomplish this we need to be absolutely clear about its nature. When we become aware that the nature of day-to-day existence is suffering, we don’t have to be miserable with the thought that

suffering is always present. Suffering doesn’t go on forever because the Buddha entered our world, gave teachings, and explained clearly what suffering is. He also taught the means by which suffering can end and described a state of liberation which is beyond suffering. We do not have to endure suffering and can, in fact, be happy. Even though we cannot immediately eliminate suffering by practicing the Buddha’s teachings, we can gradually eliminate suffering in this way, and move towards eventual liberation. This

fact in itself can help us gain peace of mind even before we have actually emerged completely from suffering. Applying the Buddha’s teachings, we can be happy in the relative phase of our progress and then at the end we will gain wisdom and liberation and be happy in the ultimate sense, as well. [[The first

noble truth]] makes it clear that there is suffering. Once we know what suffering is, we must eliminate that suffering. It is not a question of eliminating the suffering itself, but of

eliminating the causes of suffering. Once we remove the causes of suffering, then automatically the effect, which is suffering, is no longer present. This is why to eliminate this suffering, we must become aware of the second noble truth, the truth of interdependent origination (Tib. tendrel).

The Second Noble Truth The truth of interdependent origination is an English translation of the name the Buddha gave to this noble truth. It means “that which is the cause or origin of absolutely everything.” The truth of universal origination indicates that the root cause of suffering is karma and the disturbing emotions (Skt. kleshas). Karma is a Sanskrit word which means “activity” and

klesha in Sanskrit means “mental defilement” or “mental poison.” If we do not understand the Buddha’s teachings, we would most likely attribute all happiness and suffering to some external cause. We might think that happiness and suffering come from the environment, or from the gods, and that everything that happens originates from some source outside of our control. If we believe this, it is extremely hard, if not impossible, to eliminate

suffering and its causes. On the other hand, when we realize that the experience of suffering is a product of what we have done, that is, a result of our actions, eliminating suffering becomes possible. Once we are aware of how suffering takes place, then we can begin to remove the causes of suffering. First we must realize that what we experience is not dependent on external forces, but on what we have done previously. This is the understanding of karma. Karma produces suffering and is driven by the disturbing emotions. The term “defilement” refers mainly to our negative

motivation and negative thoughts which produce negative actions.

The Third Noble Truth The third noble truth is the cessation of suffering through which the causes of karma and the disturbing emotions can be removed. We have control over suffering because karma and the disturbing emotions take place within us—we create them, we experience them. For that reason, we don’t need to depend on anyone else to remove the cause of suffering. The truth of -

interdependent origination is that if we do unvirtuous actions, we are creating suffering. It also means that if we abandon unvirtuous actions, we remove the possibility of experiencing suffering in the future. What we experience is entirely in our hands. Therefore the Buddha has said that we should give up the causes of karma and the disturbing emotions. Virtuous actions result in

happiness and unvirtuous actions result in suffering. This idea is not particularly easy to grasp because we can’t see the whole process take place from beginning to end. There are three kinds of actions: mental, verbal, and physical. These are subdivided into virtuous and unvirtuous physical actions, virtuous and unvirtuous verbal actions, and virtuous and unvirtuous mental actions. If we abandon the three types of unvirtuous actions, then our actions become automatically virtuous. There are three unvirtuous

physical actions: the harming of life, sexual misconduct, and stealing. The results of these three unvirtuous actions can be observed immediately. For example, when there is a virtuous relationship between a man and woman who care about each other, who help each other, and have a great deal of love and affection for each other, they will be happy because they look after each other. Their wealth will usually increase and if they have children, their love and care will result in mutual love in the family. In the

ordinary sense, happiness develops out of this deep commitment and bond they have promised to keep. Whereas, when there is an absence of commitment, there is also little care and sexual misconduct arises. This is not the ground out of which love arises, or upon which a home in which children can develop happiness can be built. One can readily see that a lack of sexual fidelity can create many kinds of difficulties. One can also see the immediate consequences of other unvirtuous physical actions. One can see that those who steal have difficulties and suffer; those who don’t steal experience happiness and have a good state of mind. Likewise, those who

The Three Vehicles of Buddhist Practice kill create many problems and unhappiness for themselves, while those who support life are happy. The same applies to our speech although it is not so obvious. But on closer examination, we can also see how happiness develops out of virtuous speech and unhappiness results from unvirtuous speech. At first, lying may seem to be useful because we

might think that we can deceive others and gain some advantage. But the Sakya Pandita said that this is not true. If we lie to our enemies or persons we don’t get along with very well, because they are our enemies they are not going to pay attention to what we are saying anyway. It will be quite hard to deceive them. If they are our friends, we might be able to deceive them at first by

telling a lie. But after the first time, they won’t trust us any more and may see us as untrustworthy. Lying therefore doesn’t really accomplish anything. Then if we look at the opposite, a person who takes pains to speak the truth will develop a reputation for being a truthful person and out of this trust many good things will emerge. Once we have considered the example of the

consequences of lying, we can think of similar consequences relating to other kinds of damaging speech: slander, and coarse, aggressive, and useless speech. In the long term virtuous speech produces happiness and unvirtuous speech produces suffering. When we say “useless speech,” we mean speech that is really useless, not just conversational. So, if we have a good mind and want

someone to relax and be happy, even though the words may not have great meaning, our words are based on the idea of benefit and goodness. By useless speech we mean chatter for no reason at all. Worse than that is “chatter rooted in the disturbing emotions.” When we say bad things about other people because of a dislike or jealousy of them. We just gossip about people’s character. That

is really useless speech. Besides being useless, this very often causes trouble because it sets people against each other and causes bad feelings.

The same applies to “harmful speech.” If there is really a loving and beneficial reason for talking, for example, scolding a child when the child is doing something dangerous or scolding a child for not studying in school, that is not harmful speech because it is devoid of the disturbing emotions, rather it is a skillful way of helping someone. If there is that really genuine, beneficial

attitude and love behind what we say, it is not harmful speech. But if speech is related to the disturbing emotions such as aggression or jealousy, then it is harmful speech and should be given up. We can go on to examine the various states of mind and see that a virtuous mind produces happiness and unvirtuous states of mind create unhappiness. For instance, strong aggression will

cause us to lose our friends. Because of our aggressive-ness, those who don’t like us or our enemies will become even worse enemies and the situation will become inflamed. If we are aggressive and hurt others and they have friends, eventually those friends will also become enemies. On the other hand, goodness will arise through our caring for our loved ones and then extending this by

wishing to help others. Through this they will become close and helpful friends. Through the power of our love and care, our enemies and people we don’t get along with will improve their behavior and maybe those enemies will eventually become friends. If we have companions and wish to benefit others, we can end up with very good friends and all the benefits which that brings. In this

way we can see how cause and effect operate, how a virtuous mind brings about happiness and how an unvirtuous mind brings about suffering and problems. There are two main aspects of karma: one related to experience and one related to conditioning. The karma relating to experience has already been discussed. Through unvirtuous physical actions we will experience problems and unhappiness.

Likewise, through unvirtuous speech such as lying, we will experience unhappiness and sorrow. With an unvirtuous state of mind, we will also experience unhappiness as was - 9 - The Three Vehicles of Buddhist Practice demonstrated by the example of having an aggressive attitude.

All of this is related to the understanding that any unvirtuous activity produces unhappiness and pain. The second aspect of karma relates to conditioning. By acting unvirtuously with our body, speech, or mind, we habituate ourselves to a certain style of behavior. Unvirtuous physical or verbal behaviors create the habit of this type of behavior. For example, each time one kills, one

is conditioned to kill again. If one lies, that increases the habit of lying. An aggressive mind conditions one’s mind so one becomes more aggressive. In our later lives, that conditioning will continue on so that we will be reborn with a great tendency to kill, to lie, to engage in sexual misconduct, and so on. These are the two aspects to karma. One is the direct consequence of an act and the other is the conditioning that creates a tendency to engage in behavior of that kind. Through these two aspects karma

produces all happiness and suffering in life. Even though we may recognize that unvirtuous karma gives rise to suffering and virtuous karma gives rise to happiness, it is hard for us to give up unvirtuous actions and practice virtuous actions because the disturbing emotions exercise a powerful influence on us. We realize that suffering is caused by unvirtuous karma, but we can’t give up the karma itself. We need to give up the disturbing emotions because they are the root of unvirtuous actions. To give up the

disturbing emotions means to give up unvirtuous actions of body (such as killing, stealing, and sexual misconduct), the unvirtuous actions of speech (such as lying, slander and harmful and useless speech), and the unvirtuous aspects of mind (such as aggression, attachment, or ignorance). Just wanting to give up the disturbing emotions does not remove them. However, the Buddha in his great kindness and wisdom has given us a very skillful way to eliminate the very root of all the disturbing emotions through the examination of the belief in the existence of an ego or a self.

The False Belief in a Self We cannot easily understand this belief in a self because it is very deep-rooted. But if we search for this self that we believe in, we will discover that the self does not actually exist. Then with careful examination we will be able to see through this false belief in a self. When this is done, the disturbing emotions are diminished and with the elimination of a

belief in self, negative karma is also eliminated. This belief in a self is a mistaken perception. It’s an illusion. For example, if one has a flower and were to interrogate one hundred people about it, they would all come to the same conclusion that it is indeed a flower. So one could be pretty sure that it is a flower. But, if one asked a person “Is this me?” he would say, “No, it’s you.” A second person would say, “It’s you.” One would end up with one hundred persons who say its “you” and only oneself would consider it as “me.” So statistically one’s self is not verifiable through objective means. We tend to think of “me” as one thing, as a unity. When we examine what we think of as ourselves, we find it is made up of many different components: the various parts of the body, the different organs, and the different elements. There are so many of them, yet we have this feeling of a single thing, which is “me.” When we examine any of these components and try to find something that is the essence of self, the self cannot be

found in any of these parts. By contemplating this and working through it very thoroughly, we begin to see how this “I” is really a composite. Once we have eliminated this incorrect way of thinking, the idea of an “I” becomes easy to get rid of. So, all of the desire rooted in thinking, “I must be made happy” can be eliminated as well as all the aversion rooted in the idea of “this difficulty must be eliminated.” Through the elimination of the idea of “I” we can annihilate the disturbing emotions or

defilements.3 Once the disturbing emotions are gone, then the negative - 11 - The Three Vehicles of Buddhist Practice karma which is rooted in the disturbing emotions will cease.

Once the negative karma ceases, suffering will no longer take place. This is why Buddha said that the root of suffering needs to be abandoned. The first two noble truths may be summed up with two statements: One should be aware of and know what suffering is. One should give up the origin of suffering.

To summarize, once we recognize what suffering really is, then we begin by removing its causes. We do this by stopping doing unvirtuous actions which create suffering. To stop these unvirtuous activities, we eliminate them at their root which is the disturbing emotions and various unhealthy attitudes. To eradicate the disturbing emotions we need to remove their heart, which is

the belief in a self. If we do that, then we will eventually come to realize the wisdom of non-self. By understanding the absence of a self, we no longer create the disturbing emotions and bad actions and brings an end to that whole process. This is highly possible to achieve; therefore there is the third noble truth, the truth of cessation. The very essence and nature of cessation is

peace (Tib. shewa).4 Sometimes people think of Buddhahood in terms of brilliant insights or something very fantastic. In fact, the peace we obtain from the cessation of everything unhealthy is the deepest happiness, bliss, and well-being. Its very nature is lasting in contrast to worldly happiness which is satisfying for a time, but then changes. In contrast, this ultimate liberation and omniscience is a very deeply moving peace. Within that peace all the powers of liberation and wisdom are developed. It is a very definitive release from both suffering and its effect is a definitive release from the disturbing emotions which are the cause of suffering. There are four main qualities of this truth of cessation. First, it is the cessation of suffering. Second, it is peace. Third, it is the deepest liberation and wisdom. Fourth, it is a very definitive release from cyclic existence or samsara.

Cessation is a product of practicing the path shown to us by the Most Perfect One, the Buddha. The actual nature of that path is the topic of the fourth noble truth, which is called the truth of the path because it describes the path that leads to liberation. The Fourth Noble Truth The fourth noble truth is called “the truth of the path” because the path leads us to the ultimate goal. We do this step by step, stage by stage, progressively completing our journey. The Buddha’s teaching5 are called “the dharma,” and the symbol of these teachings is the wheel that you see on the roofs of temples and monasteries (as shown on the cover of this book). This is the symbol of the Enlightened One’s teachings.

For instance, if you go to Samye Ling, you will see on the roof of the temple the wheel of the dharma supported by two deer.

Why a wheel? Wheels take you somewhere, and the dharma wheel is the path that takes us to the very best place along the finest road. This wheel of the Buddha’s teaching has eight spokes because the path that we follow as Buddhists has eight major aspects known as “the eight-fold path of realized beings” or “the noble eight-fold path.” We need to follow this eight-fold path and it is essential that we know what this path is and how to practice on this path.

These eight aspects to the noble eight-fold path can be grouped into three areas: superior conduct, superior concentration, and superior wisdom which make up seven of the eight spokes with the eighth spoke, superior effort which is the quality that supports the other seven. Superior effort is needed for achieving correct conduct, correct concentration, and the development of correct wisdom.

1. Correct Meditation. When we practice the dharma it is most important to stabilize our mind. We are human beings and we have this very precious human existence with the wonderful faculty of intelligence. Using that intelligence we can, for instance, see our own thoughts, examine them, and analyze our thinking process so we can determine what are good thoughts and what are bad thoughts. If

we look carefully at mind we can see that there are many more bad thoughts than good ones. The same is true with our feelings. We find that sometimes we are happy, sometimes we are sad, and sometimes we are worried, but if we look carefully we will probably find that the happier moments are rarer than those of suffering and worry. To shift the balance so that our thoughts are more

positive, and happier, we need to do something and this is where samadhi or meditative concentration comes in, because samadhi is the root for learning how to relax. When our mind is relaxed, we are happier and we are more joyous. The word “samadhi” means “profound absorption.” If we can learn how to achieve samadhi then even if we apply this samadhi to worldly activities, it will

benefit us greatly. With samadhi our work will go well and we will find more joy and pleasure in our worldly activities. Of course, if we can use samadhi for dharma, then it will bring about really good results in our life. Some people may have been practicing dharma for some years and might feel they have achieved few results from the practice and think, “Even after all these years that I

have been meditating, there is not much to show for it. My mind is still not stable.” This thinking shows us the real need to learn how to develop samadhi or concentration so that samadhi becomes a great support for our meditation. No matter what time we can give to meditation, that time is very well-spent. Often if we do an hour of meditation it doesn’t mean we did one hour of perfect samadhi. Rather it probably means we had a half hour engaged with a lot of thoughts and a half an hour of what we could call good sitting of which about 15 minutes of this was

good samadhi. So it is really important to learn how to meditate properly, so our time meditating is most fruitful. 2. Correct Mindfulness. How do we achieve superior concen-tration? That is where the second factor of correct mindfulness is necessary. It is through mindfulness that we will be able to actually achieve samadhi. When we have mindfulness, we are very clear about what is

happening in our meditation. Also between our meditation sessions we shouldn’t lose the thread of meditation, so we should with mindfulness carry this power of the meditation into our daily life. Our mindfulness needs to be very stable, it needs to be clear, and it needs to be the strongest mindfulness so that we can achieve the highest samadhi. In the Mo onbeams of Mahamudra by the great Takpo Tashi Namgyal it says, “When one meditates one needs mindfulness which is clear and powerful. It needs to have the

quality of clarity and at the same time it needs to be stable.” Mindfulness can be just clear, but if there isn’t enough force to the mindfulness, it won’t be effective. For there to be a change in our postmeditation behavior, we need to have mindfulness and awareness. Without this clarity of awareness and without the strength of mindfulness, we won’t recognize the subtle thoughts that keep our samadhi from developing. So with these subtle thoughts, we become accustomed to a very superficial kind of meditation that will keep us from progressing. Clear and strong mindfulness, however, will allow us to recognize the obstacle of these subtle thoughts. So, strong and clear mindfulness is very important.

Normally when we speak about wisdom in Buddhism we speak of the three knowledges (Skt. prajnas) of study, contemplation, - 15 - The Three Vehicles of Buddhist Practice and meditation. Reading and studying in all sorts of Buddhist books will develop a certain kind of wisdom, but this wisdom is never advanced enough to lead us to enlightenment, or Buddhahood. So, wisdom received from books and

contemplating these teachings is limited. To develop superior wisdom that will allow us to become enlightened can only be obtained through meditation. So far we have discussed the excellent training that develops correct samadhi and correct mindfulness. Now we need the most excellent training to develop correct intention and correct view. 3. Correct Intention. Through our meditation, the

realization of the true nature of reality will develop. Actually in the meditation itself, when we have a direct awareness of reality, we may wonder, “Is this it? Is this not it? ” We will have all sorts of subtle thoughts and we need to confirm the accurateness, the rightness of the meditation that we are achieving. With time and with the right instruction we will gain

confidence and come to know what in meditation is the finest, clearest, highest view of the true nature of phenomena. There will be confidence and conviction in our belief due to primordial wisdom (Skt. jnana). The development of wisdom at this stage is called “the very best philosophical view.” After attaining this state of jnana, our postmeditation sessions will contain wisdom about the

relationship of conventional reality which allows us to cultivate the very best intention. These two together make the very best wisdom: one applies to the depth of meditation and the other to the postmeditation state. So we need to develop these and strive whole-heartedly to cultivate these two wisdoms. 4. Right View. There are many levels of the Buddha’s teachings each which has its

own way of describing what the highest view of reality is. There are the Theravada teachings, the Mahayana teachings, the Vajrayana teachings, and the Mahamudra teachings. Each Buddhist tradition has its own - 16 - The Theravada Path way of defining what is the highest view, and whichever view we hold we need to strive in developing the right view during the meditation and to develop right view during postmeditation experience.

C. Superior Conduct

We definitely need to meditate in order to train our mind. But the training of meditation needs the support of right conduct.

The importance of right conduct is not mainly for meditation but to the rest of our life, our interaction with the rest of the world. The importance of right conduct is illustrated by the fact that it has three aspects of its own. Whereas wisdom and meditation concern cultivating the finest understanding of our mind, right conduct concerns the actions of body and speech and our interrelation with other beings around us. It would be an error to think that the mind is the main thing to work on and what we do with our body and speech doesn’t matter much.

What we do with our body and speech is very important and that is what the last three paths of the eight-fold path concern themselves. There are many, many ways of explaining right conduct, but the eight-fold path does it through correct speech, correct action, and correct livelihood. 5. Correct Speech. Speech is very important to us. For instance, we can’t see another person’s mind so we judge and are judged by behavior and speech. Speech can also be very powerful.

Whether we are addressing 100 or 1,000 people, if the speech is good and beneficial then 100 or 1,000 people will be benefited; but if the speech is harmful then it can hurt 100 or 1000 people, which is much more than we can do physically. So we need to have not just correct speech, but we must train in the very best speech so that when we speak, we know what our speech is doing. Is it harming? Is it benefiting?

What techniques can we use to develop this most excellent speech? We can say prayers, such as, “Great Vajradhara, Tilopa, Naropa, Gampopa” and we can recite mantras like OM MANI PEDME HUNG. These prayers and mantras show us how to express thoughts which are most noble, which are completely beneficial, pure, and good. Part of our dharma practice is the study, the reciting of texts,

prayers and mantras which brings about the very excellent training of the best of speech. All of these activities sow the seeds for the good and right things in our mind which will afterwards become the basis for the expression of what will benefit ourselves and others. This is perhaps even more important today than it was in the past because we have such powerful means of communi-cation.

With the telephone we can contact people all over the world. With Internet and faxes the power of speech is really important, so there is even more reason to be mindful, aware, and careful of how we use this tremendous power of communication and speech. We should always be aware of its potential to either benefit or to harm others. So, training in correct speech is the first of the

three paths of right conduct. 6. Correct Action. In our busy lives, we need to do many different things and everything we do has a consequence to others and ourselves. So training to engage in the very best actions is to do what will not only bring benefit to oneself but to others. So with an excellent motivation we do excellent actions which benefit ourself and others. We need to

therefore analyze the quality of actions and to be able to discern between what is right and what is wrong. 7. Correct Livelihood. Closely connected to right conduct is having a correct livelihood. Of course, livelihood means not just our job, but also all our main daily activities that we do to have food, clothes, a roof over our head and so on. Because we do this day after day and

because it involves by its very nature our speech and our physical actions, we need to learn what is a - 18 - The Theravada Path correct and what is a negative livelihood that brings harm to others. We need, of course, to give up anything that harms others and to adopt a livelihood that is beneficial either directly or indirectly for us and for others. 8. Correct Effort. Let us go back to

the first spoke of the wheel of dharma—samadhi—that comes through the second spoke of mindfulness. These qualities won’t come by themselves unless there is the greatest effort applied to bring these qualities out. The next three spokes of wisdom, correct view, and correct thought won’t just come about one day by themselves without a great deal

of skillful, intelligent, hard work. Then the last three spokes of correct conduct, correct speech, and correct livelihood also need a great deal of effort for these values to come about. So this eighth spoke, best effort or diligence, is a support for all the other spokes. We could say that there are two types of effort. In Tibetan the word for “effort” (tsultrim) has the notion of

joy and enthusiasm, while in English “effort” has the notion of drudgery. So there are two kinds of effort. One is a vacillating sort of effort in which we jump into something and then when it becomes more difficult we slack off and the other is a steady, constant sort of effort. The first kind is more with what we associate with “enthusiasm” and the other is more stable and the very best support for the other seven spokes.

The Five Paths We can also divide the Buddhist path into five main stages because by traversing them we eventually reach our destination which is cessation of suffering. The Buddhist path can be analyzed through these stages called the five paths. The names of the five paths are the stage of accumulation, the stage of junction, the stage of insight, the stage of cultivation, and

the stage of nonstudy. Properly speaking, the first four of these are the path with the fifth one being the fruition of the other four paths. The first path is called the “path of accumulation” because we gather or accumulate a great wealth of many things. This is the stage in which we try to gather all the positive factors which enable us to progress. We try to cultivate diligence, the good qualities, and the wisdom which penetrates more deeply into the meaning of things. We commit ourselves to accumulate all

the various positive aspects of practice. We gather the positive elements into our being while at the same time working in many different ways to remove all the unwanted elements from one’sour life. We also apply various techniques to eliminate the various blockages and obstacles which are holding us back. This is called the stage of accumulation because we engage in this manifold activity which gathers these new things into our life. In ordinary life we are caught up in the level of worldliness. Even though we don’t want to be, we are still operating on a level of cyclic existence (Skt. samsara) because we are still under the influence of the disturbing emotions.

They have a very strong habitual grip on our existence. We need to get rid of these disturbing emotions in order to find our way out of samsara. Of course, we want to find happiness and peace and we know it is possible. But even with the strongest will in the world, we cannot do it overnight. It is like trying to dye a large cloth that contains many oil stains on it. It requires a great deal of effort to change its color.

So, first of all, in order to achieve the good qualities, we need to work on creating all the different conditions which will make these qualities emerge. To develop the various insights of meditation and real wisdom, we need to develop great faith and confidence in the validity and usefulness of this wisdom. Once we are convinced of its value, we need to change our habits so that

we have the diligence to do all the things necessary to make insight and wisdom emerge. Therefore, there are many factors and conditions we must generate within our life to bring about our happiness. To remove all the unwholesome factors binding us in samsara, we must uproot belief in a solid self, eliminate the various disturbing emotions which hinder us, and bring together the

many different conditions that make this trans-formation and purification possible. We talk about accumulation because we are assembling all the different conditions that make this transformation possible. We won’t be able to progress in a significant manner until we have gathered all these causes and conditions properly, completely and perfectly within ourselves. For that reason

the purpose of this stage of accumulation is to complete all the necessary conditions by gathering them into our existence. Eventually, because of the complete gathering of favorable conditions, we will reach the third path which is the “path of insight.” This is the stage during which insight into the true nature of phenomena are developed. This insight is beyond the veil of delusion. Linking the path of accumulation and the path of insight is the second path of junction. Here our inner realization, the

very way we perceive things, begins to link up with the truth of the actual nature of phenomena because we are gathering all the favorable circumstances that will eventually lead us to the actual insight itself. When we attain insight into the way things really are and this insight develops beyond the level of delusion and mistaken views, we realize that there is no self. Once there is no longer a belief in self, there are no longer any root disturbing emotions of attachment, of

Buddhist Practice aggression, or ignorance associated with the false belief in a solid self. Once there are no longer any disturbing emotions, we do nothing unvirtuous and have no more suffering. Now, it is true that once we have that insight, all suffering is immediately removed, but in another way, that is not true. This is because the delusion of a self is a habit which has been built up for such a long time and is very, very hard to remove.

For example, when we have realized that an unchanging self is a delusion fabricated by our mind, still when we hit our finger with a hammer, we experience pain. We still have the feeling, “I am suffering” because there is an enduring built-up association of “I” with the flesh of our body. Removal of that long established conditioning of self occurs through a long process of cultivating the truth of non-self. This is the fourth stage of the cultivation of insight. The fourth stage is called the path of cultivation

(gom lam in Tibetan). The word gom is usually translated as “meditation” but actually means “to get used to something” or “to accustom oneself.”6 This is why it is translated here as “the path of cultivation,” while other texts translate it as “the path of meditation.” But in this stage it is the insight into the nature of phenomena and getting used to that insight. By becoming more and more familiar with the truth of phenomena, we can remove the very fine traces of disturbing emotions and the subconscious

conditioning that still exist. Through gradual working on these, the goal of enlightenment will be attained. Through the cultivation of insight we eventually reach the goal of the fifth path which is called “the path of no more study.” Through cultivation we remove even the subtlest causes of suffering. Once this is completed we have reached the highest state and there are no more new paths to traverse making this “the path of no more study” or “the path of no more practice.” To the first two quotations from the Buddha which have already been presented, two more can be added to sum up the last two noble truths:

One should be aware of and know what suffering is.

One should give up the origin of suffering.

One should make cessation of suffering manifest.

One should establish the path thoroughly in one’s being.

We need to make the truth of cessation real, to manifest it in ourselves. We can’t just make it manifest by wishing, hoping, or praying for it. We can’t just pray to the three jewels (the Buddha, dharma, and sangha) for cessation and through their kindness they will just give it to us. The law of cause and effect, karma, makes that impossible. To attain the goal of cessation, we must

be thoroughly established on the path and the path must be properly and thoroughly developed in ourselves. One may wonder if the five paths overlap. Generally speaking, for nearly everyone, the stages of the path are consecutive and separate. Having finished the first stage, one progresses to the second stage and so on. Some texts such as the Abhidharma say that there are some individuals who can travel the paths simultaneously. But they are very exceptional persons; most persons need to complete one path

at a time. For instance, in the path of accumulation one can start on the work that is primarily associated with the path of junction, developing insight into the truth. The principle purpose for separating these two stages is to enumerate the positive factors one must gather to complete the path of accumulation and to distinguish them from the development of insight and the level of the path of junction. These paths are not completely separate. So one cannot say they do not overlap, that there aren’t several things taking place at the same time. The Four Noble Truths taught by the Buddha are very important. One can compare them to someone who is sick.

When someone is sick and has much discomfort, the first thing to do is to investigate the nature of the problem. What is the sickness? Is it in the brain? In the heart? etc. One needs to - 23 - The Three Vehicles of Buddhist Practice locate the actual problem and investigate the symptoms of the illness. Then in order to cure that person one also needs to know what is producing the

disease. Only by attacking the cause of the symptoms can one actually cure the person. This is a very good analogy for the first two noble truths. One needs to understand the nature of suffering and to know just what it entails. But just understanding the problem is not enough to bring an end to the suffering because one also needs to understand the causes of suffering, which are karma and the disturbing emotions. Then one needs to be able to eradicate the causes. The inspiration to overcome illness is, of

course, to understand all the qualities of good health and to be free from the sickness. To continue the example, the Buddha shows one all the qualities of cessation (enlightenment); that is a healthy and wonderful thing. Once one knows that the remedy exists, then one applies the remedy to what has been blocking the state of good health. One applies the very skillful remedies of the path making it possible to deal with karma and the disturbing emotions in order to obtain that good mental health. For that reason the

last two truths are like the medicine whose result is cessation of suffering. The order of working through the Four Noble Truths is not a chronological order. They are ordered logically to help us understand. The first two truths relate to suffering and its cause (samsara). First of all, the character of suffering is explained.

Once one understands the character of suffering, one will want to know what causes it so the suffering can be eliminated. The second two truths are related to nirvana. These are not arranged in order of experience because the cause of suffering must obviously come before the suffering itself.

Meditation of the Theravada Path When we study the Theravada path, we study it in the beginning from the viewpoint of intellectual understanding.

Then through meditation practice, we investigate the results that emerge. The Four Noble Truths, which are the heart of the Theravada are the view of the Theravada vehicle. The principle focus of Theravada practice is the validity of the Four Noble Truths. The actual practice of meditation within the Theravada is a little bit different from the understanding of the truths themselves. When we understand suffering and its causes, we realize that as long as we are involved with worldly affairs, we will continue creating the causes of suffering, which means we will be reborn over and over again in this vortex of samsara.

Therefore the way out is to cut this attachment to samsara.

There are several meditation practices which enable us to do this. The principle practice which enables us to cut attachment to samsara is to meditate on the impermanent nature of samsara. By meditating on impermanence, we will be less inclined to become involved in worldly activities. Attachment becomes less attractive as we begin to appreciate how quickly circumstances change. We

can see that even though kings and heroes of the past might have been very famous and wealthy, their fame and wealth did not go on forever but eventually ended. In meditation we contemplate people and the changes they undergo; we contemplate objects and their changes and the ways in which they change. When we see that there is nothing that stays the same, we begin to realize that activities and objects in samsara are not worth that much involvement and attachment. The liberation of the mind then begins to

take place. We do not completely give up everything overnight but realize that too much involvement and attachment are not very beneficial. We realize that it’s not worth spending much time with samsaric conditioning. The second principle meditation practice is on the nature of suffering in samsara. Previously, it has been explained how we can directly experience the actual emergence of suffering. As explained before, things which seem quite pleasant initially, by their very nature, must bring about suffering later.

We realize that suffering is inherent even in pleasant things. Therefore this contemplation on suffering, which is part of all samsaric phenomena, is the second point. It helps us to realize to not spend so much time and involvement in worldly things. It also helps us realize that by devoting energy to these contemplations we can profit greatly. The third main meditation is on emptiness and the fourth meditation is on the absence of ego or self. As was explained

previously, meditation on emptiness is mainly concerned with realizing that the inner phenomena which we think of as “mine” and the outer phenomena which we think of as “belonging to me” has no validity. The fourth meditation on non-self is concerned more with the idea of the “self” itself, the owner of those things. Through this meditation the delusion of self is seen.

The Examination of the Self We must separate the belief of self from the cause from which it springs. The idea of the self is

principally derived from a deluded apprehension of the aggregates (Skt. skandhas). The various aggregates, of which we are composed, are made up of many, many different individual elements. Because of the gross way in which we perceive, we don’t see the actual composite nature of reality. We tend to form these elements together and see them as just one single individual thing. Once we see these composites as one, we tend to name it, define it, and give it an identity. So when we see things with our deluded

perception we do not see many minute, short-lived components, but tend to see them as a whole and solidify them as real and existent. It is because we relate to gross wholes and give them an identity that we develop this idea of a self.

Beginningless Time

We also have a problem with time. There is no point at which we could say, “At this point there wasn’t that delusion and then at this point this mistaken view took place.” The mistake is beginningless. When we first see this word “beginningless” in Buddhist texts, it seems a rather unusual idea that a delusion could not have a beginning. However, if we examine almost anything we find

that it is beginningless. For example, take a brass pot.7 It was probably made in India, but that was not its beginning because in India that brass came from ore and we can trace the ore back through time by tracing all the minute particles of which it is made up going back forever. Nearly everything we examine is beginningless. So it is the same with the concept of self. We can trace it back, and keep going back and back and back. It is not as though there is one point in which its there and in the next moment delusion occurs. We can never find the beginning. There is something happening all the time. Because of the grossness of our perception and the mistaken consciousness that labels all objects of perception. For instance, consider the example of a flower and its seed.

This example demonstrates that one thing originates from another. Now there is a flower but when we trace back, we find there was a seed and the seed itself came from a flower and so on. The same with a brass pot, we can trace it back to some geological time and never find a point where the pot actually began. The point is that it is beginningless. When we examine our own existence, we say

there is suffering because of karma and that there is karma because of the disturbing emotions and the disturbing emotions are there because of ignorance. But we cannot find one point where this process began because if we trace it back we find that each step involves more history. We can keep going back and back and each event has even more history behind it and so on. That is why we say it is “beginningless” because we cannot answer the question, “What happened in the beginning?” It is not as though there was one ignorant thought and that was the beginning of everything.

Ignorance is taking place continually and has been occurring since this beginning without beginning. Ignorance is then a continuing mistaken perception of the minute aggregates. We conceptualize the idea of a thing which isn’t there except in the mind of the observer. That is the actual process of ignorance which takes place over and over again. Even though there are so many

different components in the skandhas, we conceive them as a mistaken “I.” Perceiving the millions and millions of particles of the pot as a single idea of “a pot” is a mistaken perception. This faulty perception continues into the future and we can trace it back into the past. The inability to perceive correctly is continuous, that process occurs again and again.

All the problems have come from that ignorance. We can never find a beginning but it does have an end because once we pierce this

delusion and reach the truth, we can find liberation from this deluded process.

The Aggregates We can make that split between the perception and what is perceived. At the beginning we may think that the perceiver is the actual self and the delusion involves only the object of perception. But actually when we examine the perception of the perceiver, we discover that this same mistake is taking place. The many minute particles are mistaken for solid things.

An analysis of the five aggregates reveals that the first aggregate deals with form and the way in which things are perceived externally. The other four skandhas deal with the internal mind—feelings, the process of perception, cognition, and consciousness. There are many elements that come together which can be mistaken for a self in just the same way one mistakes collections of minute particles as just one thing.

For instance, if we look at the aggregate of consciousness, there are many different elements of consciousness and they are always changing. For example, we have happy feelings, unpleasant feelings, fearful feelings and so on. When we look at all the contradictions which make up the mind, we see that

there is not just one unique, unchanging perceiver, but that the perceiving mind is made up of many different changing elements. We could never say any one of these are consciousness of a self. If there were a self, we could say, “Oh, yes, that is definitely the self, that is the consciousness of a self.” In fact, what we sometimes think of

as the “I” is a feeling associated with happiness or sadness or a certain kind of consciousness. Sometimes the “I” seems to be the body, sometimes the “I” seems to be the mind which perceives the body, sometimes it seems to be both. That is why the perception of a self is a delusion. The “I” is never constant. It is simply an idea associated with what is happening. If it were the same all the time, then we could point to it very clearly and say, “This is I.”

But when we think about “I” or when we talk about “I” w e continually shift from one identification to another never really establishing what is “I.” Once there is this delusion of “I,” there is the idea of “mine” and the process becomes even more complicated.

The Self in Reincarnation We may wonder if there is no “self,” then what is it that passes on in rebirth or reincarnation.8 There is rebirth, but this reincarnation is not particularly linked to a self or ego. It is not that there is a self which creates one life after another so that one develops the idea, “I have been reborn, I have been somebody else before I was reborn.” But actually what transmigrates is not the same self; it is not the same “I”

which crops up again and again or the same “I” which provokes all these different rebirths. To explain what actually happens, the Buddha taught the idea of interdependence or what is also called “interdependent origination.” Interdependent origination explains the arising of one thing from another; how one thing depends upon another for its existence. For example, a flower comes from a seed.

There is a seed which makes a shoot. The shoot sprouts leaves which eventually become flowers. The flower will then create more seeds and so on. So there is a continuity, but apart from this continuity there are great differences between the seed and the flower in shape, color, nature, etc. So there is a continuity which is a process of dependence and a process of origination.

Change takes place all the time within the context of this dependence. In the same way ignorance occurs, and because of ignorance certain actions and activities follow. And because of these actions eventually there will be some sort of rebirth.

Because of the rebirth there is aging, sickness, death, and so on. All of these factors are interdependent. One is caused by the other. There is a continuum, but there is not one thing which carries on and one thing that is unchanging. The Buddha taught that what happens from one lifetime to another occurs because of interdependence,

not a “self” which is an entity that goes on and on manifesting continuously. To understand this form of rebirth, the fact that there have been so many different Karmapas9 does not mean that they are emanations of a self. First we must examine the deluded idea of self on the level of ordinary people. We think,

“This is me, this is my one life and it has been one single life.” We think we have a self which is this life. However, when we examine this life, we find everything is changing; we do not have the same physical body; when we were a tiny baby we were only two feet tall, later growing to five feet tall. The same is true of our mind. When we were a baby, we could not even say our mother’s

name and were very ignorant. When we grew up, we learned to read and write and our mind underwent a tremendous change. We take this “me” and “mine” as being ourselves. However, when we look at this carefully, apart from the continuity that took place from one step to the other, there is not a single thing that stayed the same. Nevertheless, we tend to think of “me” as though “me” had been

the same all the time. That is an incorrect belief we have about ordinary people and about ourselves. The same is true of tulkus and the great rinpoches. Apart from the fact that there is a continuity of their - 30 - The Theravada Path noble mind and their activity which benefits beings, there is no self, no constant entity which is continuously present. Because we are deluded, we think of them as being one fixed person. The word skandha is a Sanskrit word for “aggregate” or “heap” and provides an image of a pile of different things.

Because it is a whole heap, we can say, “This is one pile.” But when we examine the heap carefully, we discover it includes many different types of things. Yet from the gross point of view we globalize and think of a heap as just one entity and relate to it as if it were just one thing. So when we examine our own existence and what is taking place from one lifetime to another, we see

millions of individual instances of many different things, so many different minutiae. Because there are so many different elements, our gross perception tends to label them as simply “I.” This process of contemplating the skandhas shows us how this delusion of self occurs. It is like a mountain which consists of many different pieces of dirt and rocks. We give this the name

“mountain” even though it is made up of millions of different particles. Because we have developed the idea of “I,” we also develop desire and these desires eventually lead to the disturbing emotions that cause suffering. The liberation from suffering (enlightenment) consists in the realization that this “I” is a delusion, a mistake, and that there is no “I” or a permanent self.

Once we have seen through that, there is no more “I” to want anything, no more “I” to dislike anything, no more “I” to possess the disturbing emotions, and therefore no more negative karma. We shouldn’t take the continuity as being unchanging. When we have the delusion of a self, for instance, between being a baby and a grown person, many things change and are different, yet we have this deluded projection about self which appears to be the same. We might say that the “I” has been there all the time

but this is not true because the continuum is not the same as an idea of self. It is not that there is a continuum which carries on in something, which would be another word for self. A continuum by its very continuity - 31 - The Three Vehicles of Buddhist Practice implies change and difference. So a continuum is tracing the way one thing changes into another and then into something else. We follow through the connection of one thing to another.

But it doesn’t mean that because there is a continuity, there is something which is the same and present all the time. So with reincarnated lamas there is just this unbroken Buddha activity. This also happens when we die. When we die, our body is no longer useful but our mind carries on. It is not as though there is a mind as a fixed entity that carries on and on. It is that there is a continuity; we can trace the change from one state of mind to another and that is what carries on. That mind carries on through

future lives, but it is not as though there is a constant thing like a self or a continuum which is nothing more than a synonym for self. To summarize, impermanence, suffering, emptiness, and absence of ego are the four main aspects of meditation which helps us to realize the truth of suffering. When we understand more about the emptiness of phenomena, we begin to see the absence of ego automatically and we will have less aggression, attachment, and ignorance. When these diminish, there will be less suffering.

Meditation on the Four Noble Truths There is nothing wrong with worldly happiness and all the good and nice things in life per se. It is very good to be happy and content and to have happiness in life. The only problem comes when we are trying to train ourselves for something higher, deeper, and more beneficial; if we become too involved with happiness and the good things of life, then they

will hold us back from our training and development. It is like a young child. If the child is playing, the child and parents are very happy. There is nothing at all wrong with that. But if the child is going to grow up, obviously the child has to learn his lessons and go to school. If the lessons are jeopardized because the child is playing all the time, he or she will never develop and go onto something useful and productive. Likewise, worldly things are not bad in themselves, but if we are aiming for something deeper and beneficial, we do not take too much time being involved with worldly things. The realization of the truth is very slow

because we are apathetic. The remedy to this apathy is to realize the Four Noble Truths completely, not superficially. When we clearly see the first truth of suffering and realize what it is and how much there is to it, we will really work to remove the causes and actually traverse the path. It is the wisdom of seeing things as they are which causes us to develop our practice. When

the Buddhist teachings say that we need to leave samsara, they point to the urgency of getting out of samsara. It is not that they are saying we have to give up eating, wearing clothes, and other worldly things. Rather we should not greatly involved and attached to samsara. The understanding of the second noble truth of universal origination involves two meditations. These two are

realizing the existence of interdependent origination and realizing the complete manifestation of interdependent origination. For the first meditation one realizes that karma and the disturbing - 33 - The Three Vehicles of Buddhist Practice emotions are the cause of all suffering and suffering doesn’t come from outer conditions, but rather from one’s previous karma. For the second

meditation one realizes that karma comes from the disturbing emotions, so one realizes the universal origination of suffering. Then one sees how powerful karma is in one’s life and this is the complete manifestation of origination. The Third Noble Truth To understand the third noble truth of the cessation of suffering, one meditates to appreciate what happens once all these difficulties and their causes have been removed. One meditates on the cessation from the view of taking away all these blocks and veils so that the good qualities will emerge.

One meditates on how one can eliminate suffering and the cause of suffering. Through this one realizes the positive quality of this cessation which is the very best peace for oneself. Realizing cessation is possible and these positive qualities will emerge and inspire one to strive on the path and develop all the qualities of peace.

The Fourth Noble Truth There are four main points to meditation on the fourth noble truth which is the path. One needs first to contemplate the presence and validity of the path to develop an intelligent awareness of the path itself and to realize that without the path of dharma one will never achieve complete liberation or freedom from one’s problems. Next one needs to be very aware of the value of the path in relation to other activities. Third, by realizing its value, one needs to actually put the path into practice. Finally, one needs to contemplate how the path is a complete release from samsara. It is actually the path which leads one to freedom from all the problems of samsara.

The Practice of the Theravada Path One of the key practices of the Theravada path is the following of the Vinaya10 which in Tibetan is dulwa which means “taming oneself.” The word is very appropriate if we consider, for example, the taming of an elephant. An elephant is very wild at first and if we want to ride it, to get it to do work, or lead it somewhere, we can’t do it. But by

gradually taming the elephant we can ride it, we can get it to work, and we can lead it around. In fact, it becomes very docile and controllable. We can apply this analogy to ourselves. At first our mind, body, and speech are very coarse and wild. Before we begin to meditate even small physical irritations can cause us to flare up and to want to fight. Even minor verbal irritation upsets us and we begin to shout, scream, and abuse others. Small mental irritations make us think all sorts of nasty and aggressive things. So in the beginning, our mind is very wild and out of control. The Theravada practice is designed to train our mind so that eventually it becomes very docile and workable and we are able to cope properly with any situation. The process of training is related to the commitments we make. We take certain vows and precepts to train ourselves.

We do this because we have become used to doing unvirtuous actions and to get rid of that habit, we make certain promises or commitments to do virtuous actions and bind ourselves to that virtuous activity. This is a very practical way of training ourselves to refrain from unvirtuous activities and accustoming ourselves gradually to virtuous activities. At first glance we may think that

the commitments and vows are really restrictive and difficult and this keeps us from doing beneficial actions. It seems like being put into a straightjacket or a prison. Actually, it is not like that at all. The Sanskrit word for this training which covers making vows and commitments is shila which means “coolness.” That was translated into Tibetan as tsultrim which means “keeping one’s discipline” in the way taught by the Buddha. This idea of coolness gives the impression of