The Basic Body

WITH THE PREPARATION we have made in the foregoing talks, perhaps at this point we could discuss tantra.

Fundamentally, tantra is based on a process of trust in ourself that has developed within us, which is like a physical body. Tantra involves respect for

our body, respect for our environment. Body in this sense is not the physical body alone; it is also the psychological realization of the basic ground of sanity that has developed within us as a result of hinayana and mahayana practice. We have finally been able to relate with the basic form, the basic norm, basic body. And that body is what is called tantra, which means “continuity,” “thread.” That body is a sense of a working base that continues all through tantric practice. Thus tantric practice becomes a question of how to take care of our body, our basic psychological solidity, our solid basic being. In

this case, the solidity is comprised of sound, sight, smell, taste, feeling, and mind. Body here is the practitioner’s fundamental sanity. The practitioner has been able to relate with himself or herself to the extent that his or her basic being is no longer regarded as a nuisance. One’s basic being is experienced as highly workable and full of all kinds of potentialities. On the tantric level, this sense of potential is called vajra, which means, “adamantine,” or “diamond,” or “indestructible.” A sense of indestructibility and a strong continuous basic body has developed.

The notion of mahamudra is prominent in tantric teaching. Maha means “great” and mudra means “symbol.” Maha here means “great” not in the sense of “bigger than a small one,” but in the sense of “none better.” And “better” even has no sense of comparison. It is “nonebetter,” on the analogy of “nonesuch.” And mudra is not a symbol as such. It refers to a certain existence we have in ourselves, which is in itself a mudra. Eyes are the mudra of vision and nose is

the mudra of smell. So it is not a symbol in the sense of representing something or being an analogy for something. In this case, mudra is the actualization of itself. The idea is that physical activity has been seen as something workable; it is something very definite and at the same time highly charged with energy.

Particularly in Buddhist tantra, a lot of reference is made to the idea that pleasure is the way, pleasure is the path. This means indulgence in the sense perceptions by basic awakened mind. This is the mahamudra attitude. Things are seen clearly and precisely as they are. One does not have to remind oneself

to be in the state of awareness. The sense objects themselves are the reminder. They come to you, they provide you with awareness. This makes awareness an ongoing process. Continuity in this sense does not need to be sought but just is.

Nobody has to take on the duty of bringing the sun up and making it set. The sun just rises and sets. There is no organization in the universe that is responsible for that, that has to make sure that the sun rises and sets on time. It just happens by itself. That is the nature of the continuity of tantra that we have been talking about. Discovering this is discovering the body.

We have a basic body, which is very intelligent, precise, sensitive to sense perceptions. Everything is seen clearly and the buddha-family principles are acknowledged. There is vajra intellect, ratna richness, padma magnetizing, karma energy of action, and the basic, solid, contemplative being of buddha.1 We have acquired such a body, which is not a new acquisition. It is the rediscovery of what we are, what we were, what we might be. With the rediscovery of

that, a sense of being develops, a sense of vajra pride, to use tantric language. That is, there is a sense of dignity, of joy, a sense of celebrating the sense perceptions, sense consciousnesses, and sense objects, which are part of the coloring of the mandala experience.

Now the dawn has awakened us. We see light coming from the east. We see the reflections on our window, showing that the light is coming out. It is about to be daytime, and we begin to wake up. That is the discovery of the basic body. In the tantric tradition, it is called the dawn of Vajrasttva. The basic discovery has been made that daylight is just about to come, and one is ready to work with one’s sense perceptions.

We wake up and then we get out of bed. The next thing, before eating breakfast, is to take a shower. That corresponds to what is called kriyayoga, the first tantric yana, which is connected with cleanness, immaculateness. You have woken up and discovered that you have a body, that you’re breathing and are

well and alive again and excited about the day ahead of you. You might also be depressed about the day ahead of you, but still there is daylight happening, dawn is taking place. Then you take a shower. This is the kriyayoga approach to life, which has to do with beautifying your body, taking care of your body, that is, the basic body we’ve been talking about.

The basic idea of kriyayoga is to purify our being of anything unnecessary. Such dirt does not provide any necessary steps toward enlightenment, but is just neurosis. Here of course we do not mean physical dirt. This is a psychological, psychosomatic type of dirt. It is neither transmutable nor workable. So we jump in the shower.

You can’t take a shower with fire and you can’t take a shower with earth or air. You have to take a shower with water, obviously. In this case water is the basic crystallization of one’s consciousness of waterness, the water element, which is connected with basic being. The chillness of water, the coldness of water, and its sparkliness are also a process of cleaning oneself, cleaning one’s body. When you take a cold shower you wake up. You’re less sleepy when the water from a cold shower pours over you. So this is also a waking-up process as well as a cleansing one.

You can’t take a shower with just water pouring on your body. You also have to use soap of some kind. The soap that you use in this case is mantras, which go between your mind and your body. Mantras are an expression of unifying body and mind. The Sanskrit word mantra is composed of mana, which means “mind,” and traya, which means “protection.” So the definition of mantra is “mind protection.” Here protecting does not mean warding off evil but developing the

self-existing protection of beingness. You are proclaiming your existence. You proclaim that you are going to take a shower because you have soap and water and body there already. Water as a symbol is related with consciousness in general; and body is the thingness, the continuity of thisness, solid basic sanity; and mantra is the tune, the music you play. When you dance, you listen to music. And you dance in accordance with the music.

At a certain point, mantra becomes a hang-up. It becomes another form of dirt. Like soap. If you don’t rinse it off, soap becomes a hangup, a problem, extra dirt on your body. So you apply the soap thoroughly and then you rinse it off with water.

The idea here is that mantra is the communicator. You make a relationship between the elements and basic sanity. The elements are the sense perceptions, the projections. This is the water. The projector is your state of mind. That which relates the projection and the projector is the energy that the mantra

brings. When communication between those two—or rather those three, including the energy of mantra—have happened properly, then the soap—the mantra—has already fulfilled its function. Then you have a rinse. You take a further shower to clean away the soap, clean away the method. At some point the methodology itself becomes a hang-up, so you rinse it away.

Having brought mind, body, and energy together properly, one begins to develop the appreciation of one’s basic being further. Your body is already clean, immaculate, and beautiful.

Now we come to the next situation, which is putting on clean clothes. That corresponds to the next yana, upayoga—putting clean clothes on your naked body, which has been beautifully cleaned and dried and is in absolutely good condition. Upayoga is basically concerned with working with action. Action here is connected with fearlessness. You are no longer afraid of relating with sense perceptions, sense pleasures, at all. You are not ashamed of putting a

beautiful garment on your body. You feel you deserve to put on beautiful clothes, clothes that are beautifully cleaned and pressed, straight from the dry cleaners. The action of upayoga is further excellent treatment of one’s body, one’s basic sanity. There is a need to be clothed, rather than presenting oneself naked all the time. Exposing one’s body without clothes becomes purely showmanship,

chauvinism. It becomes another form of ego-tripping. So the body has to be wrapped in the beautiful garment of action. This involves a sense of awareness. Every action you take is noticed; you have awareness of it. None of the actions you take is a threat to your basic sanity. Every action you take in your life situation is highly workable—there’s no conflict between the mind and the body at all. In fact, your action is another way of glorifying the beauty of your body.

This kind of appreciation of action is not a matter of watching yourself act, but rather of taking pride in your basic being in action. You don’t have a prefabricated attitude; your action is spontaneous action. In this case the point of action is dealing with emotions. Aggression arises, passion arises, jealousy arises—let them be as they are. Purified aggression is energy, purified passion is compassion, purified ignorance is wisdom, inspiration. Your

clean body is the best of your existence. On top of that you put clean clothes, which are a further adornment of your body. This is the action aspect. There is some sense of reality at this point, and that reality is that you are no longer afraid to perform your actions. You are no longer afraid of your emotions at all. The emotions are further fuel for your inspiration.

The next tantric yana is yogayana. You have bathed and put on clean clothes, and you look magnificent. You have realized your own beauty, but putting on clean clothes does not express it fully. You should take a further step, which is to put on ornaments—a beautiful necklace, beautiful rings, beautiful bracelets. Adorning your body in this way is a further way of taking care of it and appreciating its beauty, a further way of celebrating the continuity of your basic sanity. That is the yogayana.

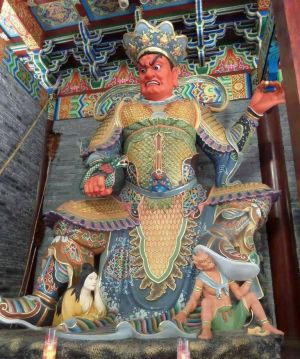

The sense of cleanness and the sense of being beautifully clothed produce the sense of ornament. They are a definite statement of the purity of basic sanity. In putting on these ornaments, you begin to associate yourself with the buddhas, the tathagatas, the bodhisattvas of the higher realms. You put on crowns and tiaras, earrings and necklaces. You behave like a king or queen on the throne. There is a complete sense of trust, a complete sense of the obviousness of your basic sanity. That is why the Buddhist tantra is pleasure-oriented.

The pleasure orientation is very important, very powerful, and very basic. If you are not pleasure-oriented, you can’t understand tantra. You have to be pleasure-oriented, because otherwise you are pain- and misery-oriented. But this is not a psychological trick of convincing yourself through positive thinking. It is an obvious, reasonable, and real thing. When you treat yourself well, you feel good. When you feel good, you dress yourself in good clothes and adorn yourself with beautiful ornaments. It is a very natural and basic way of relating to oneself.

The main qualities of tantra that come out here are basic trust and basic elegance. Elegance here means appreciating things as they are. Things as you are and things as they are. There is a sense of delight and of fearlessness. You are not fearful of dark corners. If there are any dark, mysterious corners, black and confusing, you override them with our glory, your sense of beauty, your sense of cleanness, your feeling of being regal. Because you can override fearfulness in this way, tantra is known as the king of all the yanas. You take an attitude of having perfectly complete and very rich basic sanity.

Ordinarily, this is very hard to come by. When we begin to appreciate our richness and beauty, we might get trapped in ego-tripping, because we no longer have enough hinayana and mahayana discipline related to pain and hopelessness. Pain and hopelessness have to be highly emphasized, if possible to the level of 200 percent. Then we become tamed, reduced to a grain of sand. The saint knows that he is a grain of sand and therefore is no longer afraid of ornamenting himself with all kinds of beautiful things. There is a sense of dignity, of sophistication, a sense of celebration. So one of the basic points of tantra is to learn how to use pleasure fully.

Here we are not just talking about sexual pleasure. We’re not just talking about the pleasure of being rich, or about pleasure in terms of getting high in a cosmic way. We are talking about pleasure in the sense that everything can be included. There is a sense of reality involved in pleasure. There is a sense of truth in it. As we said in talking about mahamudra, it is nonesuch, nothing better. It’s self-existingly great, not in a comparative sense. As it is, it is great and dynamic.

Student: It seems that it could be misleading to have even an intellectual understanding of this tantric material, because it would make you want to get out of your pain and suffering. So what use is it at this point?

Trungpa Rinpoche: You cannot get into it unless you have a good and real understanding of pain and hopelessness. Without that, you are nowhere near it. It would be misleading if we presented it right at the beginning and you had no idea at all of hinayana and mahayana. That would be misleading and very dangerous. You would turn into an egomaniac. But once you have an understanding of the necessity and simplicity of pain and the necessity and simplicity of compassion of the bodhisattva’s path, you can begin to look into other areas. Hinayana and mahayana are necessary and very important.

Student: Rinpoche, what is the relationship between negativity and the energies that are transformed into the five wisdoms?2 I’ve been becoming more aware of the energy of negativity and how alive it is, but I don’t see where it fits into the pattern of the five wisdoms.

Trungpa Rinpoche: The whole point is that within itself, negativity is self-existing positive energy. If you have a really clear and complete understanding of negative energy, it becomes workable as a working base, because you have basic ground there already. Do you see what I mean?

S: No.

TR: Negative energy is no longer regarded as threatening. Negative energy is regarded as fuel for your fire, and it is highly workable. The problem with negative energy is that negative energy does not enjoy itself. It doesn’t treat itself luxuriously—sybaritically, one might say. Once the negative energy begins to relate to itself sybaritically in its own basic being, then negative energy becomes a fantastic feast. That’s where tantra begins to happen. S: Okay. So much for negativity in itself. What then is the relationship to the five wisdoms?

TR: The five wisdoms begin to act as the clear way of seeing your negativity. In mirrorlike wisdom, vajra, aggression is seen as precise, clear-cut intellect. The wisdom of equanimity, ratna, is related with a sense of indulgence and richness; at the same time, everything is regarded as equal, so there’s a sense of openness. In discriminating awareness, padma, passion is seen as wisdom in that passion cannot discriminate itself anymore, but this

wisdom does perceive it discriminatingly. In the wisdom of the fulfillment of action, karma, instead of being speedy, you see things as being fulfilled by their own means, so there is no need to push, to speed along. In the wisdom of dharmadhatu, all-encompassing space, which is related with the buddha family, rather than just seeing stupidity, you begin to see its all-encompassingness, its comprehension of the whole thing.

The wisdoms become a glorified version of the emotions, because you are not a miser. One of the problems is that in relating with the samsaric emotions, we behave like misers; we are too frugal. We feel that we have something to lose and something to gain, so we work with the emotions just pinch by pinch. But when we work on the wisdom level, we think in terms of greater emotions, greater anger, greater passion, greater speed; therefore we begin to lose our

ground and our boundaries. Then we have nothing to fight for. Everything is our world, so what is the point of fighting? What is the point of segregating things in terms of this and that? The whole thing becomes a larger-scale affair, and ego’s territory seems very cheap, almost inapplicable or nonexistent. That is why tantra is called a great feast.

Student: Is the thing that prevents us from relating to the world in a tantric way right now the fact that we have a sense of self? Are you saying that we have to go through the hinayana and the mahayana first in order to break down our sense of self so that we can relate to tantra? Trungpa Rinpoche: If you think on a greater scale as vajrayana, or tantra, does, you have no idea of who is who and what is what, because no little areas

are kept for a sense of self. Mahayana works with more developed people, hinayana with people who are less developed but still inspired to be on the path. Each time they relate with the path, they lose a pinch of self, selfishness. By the time people get into vajrayana, the selfishness doesn’t apply anymore at all. Even the path itself becomes irrelevant. So the whole development is a gradual process. It is like seeing the dawn, then seeing the sunrise, then seeing the sun itself. Greater vision develops as we go along.

Student: How can you have a sybaritic relationship with negativity. Trungpa Rinpoche: That’s the greatest of all.

S: I’m sure it is, but I don’t understand it.

TR: It’s like putting seasoning on your food; if you don’t, you have a bland meal. You add color to it, and it’s fantastic. It’s very real and alive. You put salt and spices on your dish, and that makes it a really good meal. It’s not so much a sense of indulgence as of appreciating the meal. Student: So far in this seminar, you have skirted the use of the word shunyata.3 I was wondering about the shunyata experience, which you have characterized in the past as appalling and stark. How does that relate with the sense of isness or being? I had a nihilistic feeling about shunyata. It seemed very terrifying and claustrophobic, whereas the idea of isness seems very comfortable and expansive.

Trungpa Rinpoche: Isness feels good because you know who you are and what you are. Shunyata is terrifying because you have no ground at all; you are suspended in outer space without any relationship at all to a planet.

S: Shunyata is characterized in some literatures as ultimate point, a final attainment.

TR: That’s a misunderstanding, if I may say so. Shunyata is not regarded as an ultimate attainment at all. Shunyata is regarded as no attainment. Student: I’m wondering about the transition to tantra from the earlier discipline. It seems one might get hung up on the hinayana and mahayana. The hopelessness begins to have a kind of dignity, and you might get attached to it. It seems to be a very abrupt kind of transition, and it could be very hard to switch over.

Trungpa Rinpoche: You are able to switch over because of your sense of sanity. You are no longer interested in whether the different yanas are going to be kind to you or unkind. You don’t care anymore. You are willing to face the different phases of the various yanas. And you end up with vajrayana. S: That takes a lot of bravery.

TR: That is the whole point. Relating with the samaya vow and the vajra guru takes a lot of discipline and a lot of bravery.4 Even the highlevel bodhisattvas supposedly fainted when they heard the message of vajrayana.

Student: When you reach the point of transition between mahayana and vajrayana, do you have to give up your cynicism about the teachings and the teacher and about yourself that you have during hinayana and mahayana?

Trungpa Rinpoche: I think so. A that point you become very clear, and cynicism becomes self-torture rather than instructive and enriching. At that point, it is safe to say, there is room for love and light. But it is sophisticated love and light rather than simple-minded lovey-lighty.