The Bodhisattva Concept by Robert Ellis

Written for the AQA syllabus by Robert Ellis, formerly a member of the Triratna Buddhist Order and a former Head of RS in a 6th-form college.

Revision of the Mahayana

We will now move on to consider aspects of Buddhist thought that are specific to the Mahayana. It will be helpful to revise your work from last year about the features of the Mahayana before going on. See if you can answer these questions at least briefly:

1. When and how did the Mahayana begin to be separated from the Hinayana?

2. What are the differences between the terms Hinayana, Theravada and Early Buddhism to describe non-Mahayana types of Buddhism?

3. What emphases are distinctive of Mahayana teaching?

4. What are the Mahayana scriptures, and what attitude do Mahayanists take to them?

5. What similarities and differences are there broadly between Theravada and Mahayana monasticism?

We will now be focussing particularly on three areas: the Mahayana doctrines concerning the Bodhisattva (which apply to nearly all schools of the Mahayana), The Mahayana view of the status of the Buddha (particularly that of the Yogacara School) and the Doctrine of Emptiness (which is specific to the Madhyamika School but widely influential across the Mahayana).

What is a bodhisattva?

The term 'bodhisattva' literally means 'one who has enlightenment as his/her essence', from bodhi (awakening or enlightenment) and sattva (essence). It is not simply another term for a Buddha, though: a bodhisattva is a being who is destined for enlightenment rather than one who has gained it already. A bodhisattva is also normally thought of as consciously working towards enlightenment: you can’t call someone a bodhisattva just because they might be enlightened in the future if they haven’t started making an effort yet. For this reason, the earliest use of the term 'bodhisattva' refers to Siddhartha Gautama before he gained enlightenment, and also in his previous lives.

In the Theravada, as in Early Buddhism, though, this is the only use of the term. There is only one Buddha per age, who is the trailblazer who discovers the Dharma. So for each age, at any rate, there is only one bodhisattva.

One of the difficulties this created in Early Buddhism was that there seemed to be two classes of enlightenment: the trailblazer’s enlightenment of the Buddha and the follower’s enlightenment of the arhat. At the same time, by about 500 years after the death of the Buddha, a reaction was developing against a narrowness that it was thought was developing in the tradition. To become an arhat, it seemed, all one needed to do was to become a monk or nun, follow the rules, get on with your practice of the Eightfold Path and you’d get there. To the early Mahayanists, this seemed a bit over-focussed on self-fulfilment to the exclusion of the Enlightenment of others. Mixed in with this there may have been some lay resentment of over-sheltered monks. After all, the Buddha had devoted fifty years of his life after enlightenment to helping others.

So, as an alternative two interlinked new ideas developed: Firstly, that the arhat had not gained full enlightenment, and that everyone could go on to gain the full enlightenment of the Buddha. To become a full Buddha, not just an arhat, was the ideal for everyone, whether monks or lay-people. This was the ideal expressed particularly in the Lotus Sutra. Secondly, that until such time as we all reach Buddhahood, we should become bodhisattvas. This meant that there was no longer only one bodhisattva per age, but potentially any number. The bodhisattva is striving for enlightenment for all sentient beings from the start.

The bodhisattva vow

The mark of a bodhisattva in the Mahayana is that he/she has taken the bodhisattva vow. The bodhisattva vow is solemnly made before one’s master in a special ritual, and involves four pledges:

- To save all beings from difficulties.

- To destroy all evil passions.

- To learn the truth and teach others.

- To lead all beings to Buddhahood.

This is obviously a mind-bogglingly immense undertaking, but the bodhisattva vows to do it nevertheless. However many beings there may be, the bodhisattva will save them from samsara and lead them not just to arhatship, but to Buddhahood. What’s more, the bodhisattva will not 'cross the threshold' into enlightenment him/herself, until this goal is achieved. If the bodhisattva were to do this, they would pass into parinirvana and no longer be reborn, and so would no longer be able to help other beings, so the bodhisattva is traditionally envisaged as pausing on the brink, turning back, and voluntarily taking rebirth to help others.

However, the bodhisattva does not work for himself or herself alone until he/she reaches this exalted point: rather he/she sets out from the start to save all sentient (i.e. conscious) beings and is as much concerned with their progress as his/her own. Related to this is the doctrine of anatta (insubstantiality) and the implications the Mahayana believe this to have: that we are not in fact ultimately distinct from others, but actually our interests are at one with theirs. If the idea that we exist separately from others is ultimately one of the illusions of samsara, it would seem contradictory that we should gain enlightenment for ourselves. The Mahayana doctrine of the bodhisattva faces this difficulty head-on.

For this reason it may be helpful not to take the idea of the bodhisattva pausing at the threshold of enlightenment too literally. This may simply be a way of expressing the insight that our enlightenment is ultimately one with that of others. To follow the bodhisattva ideal, then, we may need to give up the idea of 'gaining enlightenment' (as though enlightenment was a sort of thing one gains), and simply think of making progress alongside others.

Preparation for the vow

Naturally, such an enormous vow is not to be undertaken lightly, and in the Mahayana tradition it is only taken as the culmination of a period of intense preparation. This preparation attempts to bring about the arising of the Bodhicitta (the aspiration towards enlightenment), the desire to bring about the enlightenment of all sentient beings which should accompany a sincerely-made bodhisattva vow. The vow should only be made as the external sign of this internal opening, which involves a shift in perspective rather like that of a religious conversion. Sangharakshita describes the arising of the bodhicitta as 'the most important event that can occur in the life of a human being'.

The period of preparation preceding the vow is thus devotional in nature, attempting to open the heart to the spark of enlightenment which arises from the development of wisdom and compassion. This devotional practice is known as the Supreme Worship. One of the most important texts in the Mahayana, the Bodhicaryavatara, was written in the eighth century by Shantideva to be used as a liturgy in this supreme worship.

Task

Look at the Bodhicaryavatara on the web. Take brief notes on anything you find which helps to illustrate the nature of the bodhisattva or the bodhisattva vow (there are various details you can skip here).

Bodhisattvas of the Path

A person who has taken the vow then becomes a Bodhisattva of the Path. This person will have a genuine aspiration to bring all beings to enlightenment, but may still have a long way to go themselves. According to Mahayana tradition, the bodhisattva needs to practise the 6 or the 10 Perfections and ascend through the Ten Bhumis, which are levels of attainment of a bodhisattva.

Take notes from Cush p. 102-104 on the 6 or 10 Perfections and the 10 Bhumis. Alternative sources are Peter Harvey An Introduction to Buddhism p.122-4, or (for more detail) Paul Williams Mahayana Buddhism p.204-214.

Life as a bodhisattva is tough. According to Mahayana tradition, a bodhisattva needs to be able to give up absolutely anything for the sake of other beings, including his own life over and over again. If the bodhisattva is not yet generous enough to do this, he/she still has a way to go. The bodhisattva also needs infinite reserves of patience, because it will take a countless number of lifetimes to reach his/her goal, and humble: he/she can’t even take pride in saving sentient beings who really ultimately exist (see following section on Emptiness). The bodhisattva should even be willing to save others from bad karma by doing necessary deeds for which they would subsequently suffer (such as murder), on the occasional extreme occasion when this would be helpful to leading all beings to enlightenment.

In one Mahayana text, the Perfection of Wisdom in 8000 verses, the bodhisattva is compared to a hero who is lost in a terrible forest with his family. Here the forest represents samsara and his family is all other beings. The hero wouldn’t think of abandoning his family there to save himself. Instead he would do his utmost to reassure them and save them from peril.

Advanced and symbolic bodhisattvas

Bodhisattvas who have got close to the brink of enlightenment, beyond the sixth bhumi, are sometimes known as transcendental bodhisattvas. It is these bodhisattvas that are really in a position to start saving all sentient beings using their skilful means without making mistakes. It is these advanced bodhisattvas which are believed in the Tibetan tradition to take voluntary rebirth as incarnate lamas (tulkus), and to have control over the point of their new birth. The Fourteenth Dalai Lama, the religious leader of Tibetan Buddhists and former political leader of Tibet, is believed to be one such bodhisattva.

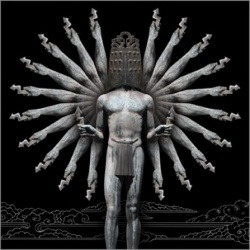

Advanced bodhisattvas are also widely represented symbolically in the Mahayana, both in visualisation practices and in art. These figures represent enlightenment generally, as do Buddha figures of various types, but in particular the qualities of the bodhisattva, of endless dedication to bringing all beings to Buddhahood. Some of the most widely known of these are Avalokiteshvara (“Lord who looks down”), the Bodhisattva of Compassion, and Manjushri, the Bodhisattva of Wisdom. Avalokiteshvara is often represented with 1000 arms, each of which is reaching out to help all sentient beings. In Chinese Buddhism, Avalokiteshvara became the widely revered female bodhisattva Kwan-Yin, and in Japanese Buddhism Kannon (after which the electronics company Canon is named!).