The Buddhist I-Ching and the Tibetan Image of Confucius

Buddhist tradition

The depictions of Kong tse 'phrul gyi rgyal po (i.e. the Tibetan name of the Chinese sage Confucius) in the Tibetan literature of the Buddhist tradition are found mainly in the context of Sino-Tibetan divination (nag rtsis). The Sino-Tibetan divination is said to have originated in China.

Fascinating passages in Tibetan literature show how Tibetans relate China with divination and Buddhism. According to bShad mdzod yid bzhin nor bu (The Treasury of Sayings, the Wish-Fulfilling Gem), which was probably written in the sixteenth century,[1] the element-divination ('byung rtsis) appears in China in the following circumstances:

"Since the (people living on the] land of the Chinese king cling overtly to the heretic knowledge, they do not involve in the Dharma of the Bhagavan. To this [observable fact], [the Buddha) prophecied to Mañjusri by saying that ‘Since the (people living on the] land of China will not believe in my Dharma of the ultimate reality and the elements of the conventional reality are included in the science of calculation, Mañjusri! Subdue them with your (knowledge of the science of] calculation!'"[2]

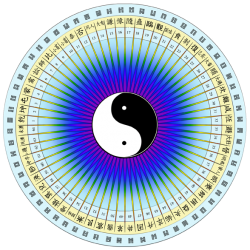

Mañjusri, the Bodhisattva symbolizing wisdom, was assigned by Buddha to subdue the Chinese by means of the science of calculation (rtsis), because the Chinese are fond of heretic knowledge rather than Buddhist teachings. Therefore, the narration which follows the above citation portrayed how Mañjusri emerged from a gold-colored lotus in a lake situated on the eastern side of the Chinese sacred mountain Wutai shan 五台山 (Tibetan name: ri bo rtse lnga) and the appearance of a divinational turtle.[3] These all aimed at subduing the Chinese people. At the same time, the science of divination was adopted into the scope of Buddhism. This was undertaken by way of corresponding the terms of element-divination with the Buddhist concepts, e.g. the five elements ('byung ba lnga) to the five wisdoms (ye shes lnga); the eight spar kha to the "Eight-fold Noble Path" ('phags pa'i lam brgyad); the nine sme ba to the "Nine stages of vehicles" (theg pa rim dgu); the twelve year-cycles (lo skor bcu gnyis) to the twelve deeds of Buddha (mdzad pa bcu gnyis); the twelve months (zla ba bcu gnyis) to the twelve links of interdependent arising (rten 'brel bcu gnyis); the eight planets (gza' chen brgyad) to the eight collections of conciousnesses (rnam par shes pa tshogs brgyad); the 28 constellations (rgyu skar nyi shu rtsa brgyad) to the 28 Ishvaris (dbang phyug ma nyi shu rtsa brgyad) etc.[4] Mañjusri's instruction in the element-divination ('byung rtsis) was given upon the request of several groups of supernatural beings. After the requests of such groups led respectively by the goddess lHa mo rnam rgyal ma, the king of Nagas Klu rgyal 'jog po sbrul mgo bdun pa and the Brahman Bram ze gser kya, Kong tse[5] 'phrul gyi rgyal po together with three other kings of magic ('phrul gyi rgyal po) also asked for instruction in elementdivination from Mañjusri.[6] In a reply, Mañjusri expounded 31 tantra sections of element-divination as well as 360 gab rtse. The term gab rtse, which appears quite often in passages relating to Kong tse 'phrul gyi rgyal po in Bonpo literature, comes into sight along with "element-divination" ('byung rtsis) in bShad mdzod yid bzhin nor bu. In later Buddhist literature, "gab rtse" disappears and "element-divination" ('byung rtsis) is often replaced by its equivalence "Sino-Tibetan divination" (nag rtsis). Nevertheless, every now and then "'byung rtsis" is still used. According to the 5th Dalai Lama Ngag dbang blo bzang rgya mtsho (1617-1682), after Mañjusri handed down the Sino-Tibetan divination in Wutai shan, the teaching prospered in China. Texts of Chinese divination were brought to Tibet first by Princess Wencheng, the Chinese wife of Srong btsan sgam po.[7] By applying the concepts which Mañjusri passed on to Kong rtse 'phrul gyi rgyal po as foundation of calculation, like those of year (lo), month (zla), day (zhag), time (dus tshod), "vital force" (srog), "body" (lus), "prosperity" (dbang thang), "fortune" (rlung rta), spar kha, sme ba, etc., diverse calculations were developed in[8] Tibet. The proposition that Mañjusri handed down the knowledge of calculation to Kong tse 'phrul gyi rgyal po is modified by the regent of the 5th Dalai Lama sde srid Sangs rgyas rgya mtsho (1653-1705) in his monumental work about Tibetan science of calculation Baidurya dkar po (The White Beryl): "As to Kong tse 'phrul gyi rgyal po, by merely meeting [with Mañjusri) he understood spontaneously the 84000 dPyad and 360 gTo."[9] In agreement with the above mentioned two works, Kong tse 'phrul gyi rgyal po also appears in a context of the transmission of element-divination in Bai rya dkar po. Yet his role as a student of element-divination changed in Sangs rgyas rgya mtsho's depiction. Instead of learning from Mañjusri by listening to his instruction of element-divination, Kong tse 'phrul gyi rgyal po knew how to perform the dPyad healing method and the gTo-ritual by merely seeing Mañjusri. gTo refers to a certain type of ritual performed to avoid or to eliminate disaster as well as to bring about luck and happiness. The meaning of dPyad is, according to the Bonpo tradition, related to medical treatment.[10] The association of Kong tse 'phrul gyi rgyal po with gTo reminds us of the texts in Bonpo brTen 'gyur attributed to Kong tse/ Kong tse 'phrul rgyal. (.....)

Footnotes

- ↑ E. Gene Smith (Among Tibetan Texts, History and Literature of the Himalayan Plateau, Boston: Wisdom Publications, 2001, 213) dates the writing of this work to the last half of the fifteenth century or the early years of the sixteenth. According to a paragraph in bShad mdzod yid bzhin nor bu, the exact date and time of writing was recorded in the Tibetan way of dating: at the iron-dog time on the irondragon day of the earth-rabbit month in the fire-tiger year, when the author was 50 years old. See the Tibetan text in Among Tibetan Texts, History and Literature of the Himalayan Plateau, 212. Believing they all refer to years, Smith failed to identify the date of writing in four compartments of year, month, day and time. Instead, he provided four sets of four years in western calender with which he himself was not satisfied (213). According to Table 8 in Te-ming Tseng, Sinotibetische Divinationskalkulation (Nag-rtsis) dargestellt anhand des Werkes dPag-bsam ljon-šiṅ von bLo-bzaṅ tshul-khrims rgya-mtsho (Halle, Saale: IITBS GmbH, International Institute for Tibetan and Buddhist Studies, 2005, 78-79), the firetiger year with sme ba two-black are the years of 1026, 1206, 1386, 1566, instead of 1086, 1266, 1446, 1626 as suggested by Smith. Combining these dates with the other information provided (212), one could conclude that bShad mdzod yid bzhin nor bu was finished in 1566 and that Don dam smra ba’i seng ge was born in 1516.

- ↑ Don dam smra ba'i seng ge, Lokesh Chandra, ed., A 15th Century Tibetan Compendium of Knowledge, The bShad mdzod yid bzhin nor bu by Don dam smra ba'i seng ge. Śata-piṭaka Series, vol. 78. (New Delhi: Jayyed Press, 1969), 418.2: "/rgya nag rgyal po'i rgyal khams de mu teg [read "stegs"] gi rig byed la mngon par zhen pas/ bcom ldan 'das kyi chos la ma tshud par/ 'jam dpal la lung bstan pa/ rgya nag po'i rgyal khams 'di/ nga'i don dam chos la mi mos shing/ kun rdzob 'byung bas rtsis la 'dus pas/ 'jam dpal khyod kyi rtsis kyis thul cig gsungs nas lung bstan te/ ".

- ↑ Don dam smra ba'i seng ge, bShad mdzod yid bzhin nor bu, 209v6-210v1.

- ↑ Don dam smra ba'i seng ge, bShad mdzod yid bzhin nor bu, 210v1-210v4.

- ↑ In bShad mdzod yid bzhin nor bu "Kong tse" was written as"Gong rtse".

- ↑ Don dam smra ba'i seng ge, bShad mdzod yid bzhin nor bu, 212v2: "/de nas gong rtse 'phrul gyi rgyal po dang/ byi nor 'phrul gyi rgyal po dang/ ling tshe 'phrul gyi rgyal po dang/ dbang ldan 'phrul gyi rgyal po dang bzhis/ rang rang gi ci phrod phrul nas nas zhus pa/ kyai ma ho/ /'jam dbyangs gzhon nu lha mi 'dren pa'i dpal/ thams cad mkhyen pa'i the tshom so sor gcod/ 'dod pa'i don grub dgos 'dod skong mdzad pa'i/ bdag cag 'gro ba mi'i rigs rnams ni/ ma rig dbang gis bdag tu 'dzin pa skyes/ 'khrul pa'i dbang gis rtag tu 'khor bar 'khyams/ skye rga na 'chi'i sdug bsngal dang/ dar (213r1) gud phyugs dbul rnams dang gdon la sogs/ 'jigs pa brgya dang bcu gnyis las bsgral phyir/ 'byung rtsis chen po bdag la stsal du gsol/ zhes zhus pas/ 'phags pas bka' stsal pa/ 'gro ba sems can 'byung ba lnga las grub/ 'byung ba lnga rnams 'byung bdud 'byung bas gcod/ de phyir 'byung rtsis chen po bshad/ ces gsungs nas/ ma hā nag po rtsa ba'i rgyud/ 'jig rten sgron ma sngar rtag gi rgyud/ rdo rje gdan phyi rtag gi rgyud/ 'byung don bstan pa thabs kyi rgyud/ mkhro' ma rdo rje'i gtsug gi rgyud dang/ yang rgyud bar ma gsungs/ ging sham rin po che'i dmigs gsal kyi rgyud/ zang ta rin po chen gson gyi rgyud/ a tu rin po che dmigs gsal gyi rgyud/ phung shing nag po ngan thabs kyi rgyud/ zlog rgyud nag po lto'i rgyud lnga (213v1) gsung/ yang rgyud phyi ma 'byung ba lnga rtsegs kyi rgyud/ 'jam yig chen po phyi'i rgyud/ ka ba dgu gril spar sme'i rgyud/ sdong po dgu 'dus rab chad bu gso'i rgyud/ gser gyi nyi ma gying shong bag ma'i rtsis dang lnga gsungs so/ /de ltar lto 'byung rtsis kyi rgyud sde sum bcu rtsa cig gsungs so/ /gab rtse sum brgya drug cu gsungs so/ ".

- ↑ Ngag dbang blo bzang rgya mtsho, rTsis dkar nag las brtsams pa'i dris lan nyin byed dbang po'i snang ba (in Thams cad mkhyen pa rgyal ba lnga pa chen po Ngag dbang blo bzang rgya mtsho'i gsung 'bum, reproduced from Lhasa edition, Gangtok, Sikkim: Sikkim Research Institute of Tibetology, 1991-1995, vol. wa: 568), 3v6: "rgya nag gi rtsis gzhung yang 'phags pa 'jam dpal dbyangs kyis ri bo rtse lngar gsungs nas/ ma hā tsi na'i rgyal khams su dar ba rgya mo bza' kong jos thog mar bod du bsnams (4r1) nas mchog dman kun gyis spang blang bya bar med du mi rung ba ste". See also Giuseppe Tucci, Tibetan Painted Scrolls, 2 vols. (Rome: La Libreria della Stato, 1949; repr., Bangkok: SDI Publications, 1999), 136.

- ↑ Ngag dbang blo bzang rgya mtsho, rTsis dkar nag las brtsams pa'i dris lan nyin byed dbang po'i snang ba, 10r1: "/'phags pa 'jam dpal gyis kong rtse 'phrul gyi rgyal po la gnang ba'i/ lo zla zhag dus tshod/ srog lus dbang thang rlung rta spar rme sogs rtsis gzhir bzung nas/ gson rtsis la mi 'gyur rtsa ba'i rde'u drug/ gcod dral gyi rde'u nyi shu rtsa gcig/ rda'u zhe bdun ma/ bcu bzhi ma/ brgyad ma/ nad rtsis la/ thang shing gi rtsis/ tshe rtsis la/ rgya ma phang gi rtsis/ gza' bzhi ma klung gi rtsis/ lha dpal che gsum gyi rtsis/ ging gong gnyen sbyor gyi rtsis/ gshin rtsis la/ zang 'khyam rnam grangs mi 'dra ba bcu gsum sogs rgya nag gtsug lag gi rtsis rnams kyang gong du bshad pa ltar yid bzor bsdu nus so/". Tucci (Tibetan Painted Scrolls, 136) claimed that the "system (of nag rtsis) is founded on the works of Kong tse, the incarnation of 'Jam dbyangs, who revealed it on the Ri bo rtse lnga". I have not found the corresponding passage in Ngag dbang blo bzang rgya mtsho's work.

- ↑ Sangs rgyas rgya mtsho, Phug lugs rtsis kyi legs bshad bai dūr dkar po, 2 vols. (Bod kyi shes rig dpe skrun khang, 1996), sTod cha, 237: "/Kong tse 'phrul gyi rgyal po ni/ /mjal ba tsam gyis dpyad brgyad khri/ /bzhi stong sum brgya drug cu'i gto/ /rang bzhin babs kyis thugs su chud/".

- ↑ Both Snellgrove (The Nine Ways of Bon, Excerpts from gZi-brjid, 301) and Karmay ("A General introduction to the History and Doctrines of Bon," 141) interpreted dPyad as "diagnosis/ diagnoses". An example of illness management by employing a four-fold method, in which gTo and dPyad are applied, was illustrated by Karmay (141).

Source

Excerpt from: The Tibetan Image of Confucius By Shen-yu Lin

v-age.travelblog.fr