The Buddhist View: Sutra, Tantra and Dzogchen

David Paul Boaz (Dechen Wangdu)

The Vajrayana, The Tibetan Buddhist Mahayana vehicle consists of the Kagyu, Sakya and Gelug Schools and are referred to as the New Translation Tantra Schools (Sarma) that developed after the translations of Rinchen Sangpo (958-1055), during the time of Atisha and Marpa. His Holiness the Dalai Lama has

shown that the view and basic structure of these schools are essentially the same as the Indian Middle Way Consequence School (Madhyamaka Prasangika) of Nagarjuna (second century), Chandrakirti (7th century), and Tsongkhapa (14th century) is considered to be the epistemic foundation of the Nyingma School's

nondual Dzogchen, the Great Perfection. H.H. the Dalai Lama has refered to the great Prasangika Middle Way teaching as “that perfect harmony between the

teachings on emptiness (Madhyamaka), and the teachings on the clear light (Yogachara).” This sutra school evolved from Nagarjuna’s 2nd Century Madhyamaka (Uma), the great Mahayana development stage teaching of the Two Truths (relative-empirical and absolute or ultimate) that grew from the ancient Pali Canon

(The Tripitaka, 4th Century B.C.E.) that continued the august tradition of the Vedas, Upanishads and Vedanta— the Sanatana Dharma or Hindu religious complex in which Buddhism arose. This Middle Way teaching then entered China with Bodhidharma (c.521 C.E.), the twenty-eighth patriarch of Indian Buddhism

and the first patriarch of the Ch’an/Zen tradition. In China, Indian Mahayana Buddhism blended with the Taoism of the T’ang and Sung periods to give rise to Ch’an and T’ien T’ai in the 6th century. In the late 12th century Ch’an entered Korea, then Japan as Zen with Eisai and Dögen, founders of the Zen

Rinzai and Soto Zen schools, respectively. T’ien T’ai entered Japan (Tendai) with Saicho in the 8th century. This great Chinese tradition is expressed in the Chinese Canon (983). The Madhyamaka teaching also entered Tibet in the 8th century from India with Shantirakshita, Kamalashila and in the Shambhala

teaching of Padmasambhava, the Second Buddha, where it assimilated the indigenous Bön religion. The Tibetan transmission reached its pinnacle through the translation and transmission of Tsongkhapa (1357-1419), the founder of the Dalai Lama’s Gelug School in the 14th century. This Tibetan tradition of the

Buddha’s teaching is voiced in the Tibetan Canon (1742). The 19th and 20th century Tibetan non-sectarian rime movement further developed and aligned the Buddhist Middle Way teaching with the nondual views of the highest or innermost tantras of both the New Translation Schools (Highest Yoga Tantra), and the

earlier Nyingma School (Dzogchen). . . . the basic thought of Ga-gyu, Sa-gya, and Ge-luk is the same with respect to the philosophical views in that they are all of the Middle Way Consequence School. - H.H. The Dalai Lama (Kindness, Clarity and Insight, 1984)

Dharma in a Cold Climate: the Supreme Teaching. But what of the Secret Mantra translations of this earlier Tibetan dissemination, the Old Translation School of Nyingma, with its supreme non-dual teaching of Dzogchen, The Great Perfection? This ancient teaching dates back to its historical founder, Garab Dorje (Prahevajra) in 2nd century C.E. Uddiyana (Orgyan). From there it spread to Zhang Zhung, and in the 8th century to Tibet with the great translations

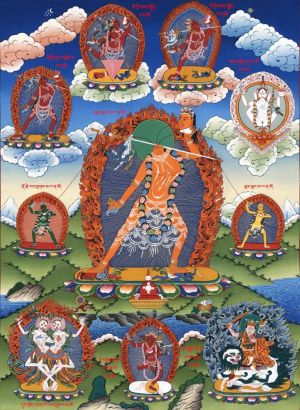

of Vairochana, Shantirakshita and Padmasambhava, as we have seen. According to Chögyal Namkhai Norbu, certain Dzogchen (Skt. Mahasandi) tantras reveal that the Dzogchen lineage includes the “Twelve Teachers of Dzogchen” (see Dodrupchen Nyima’s primary text, Tantric Doctrine According to the Nyingmapa School), prehistoric masters some of whom pre-date even the ancient Bön Dzogchen master Shenrab Miwoche who taught in Olmo Lung ring circa 1600 B.C.E.

Indeed, the Grathal gyur Tantra and other texts state that the great nondual Dzogchen Ati teaching, by whatever name, has arisen in inhabited star systems for may kalpas, and will endure long after the earth and its sun have passed. In our star system its innermost secret teaching—mengagde/upadesha—is considered by many Buddhist masters to be the quintessential nondual teaching. According to His Holiness, who bases his analysis in part upon the

definitive teaching of the aforementioned Nyingma Master, the Third Dodrupchen Jigme Tenpe Nyima (18651926), the tantric view of Dzogchen, and the Middle Way of sutra and the lower tantras are not essentially the same, although the practices of the path are similar and its Result or Fruit— Buddhahood—is the same (H.H. The Dalai Lama, Dzogchen, 2000). However, the view of the highest, non-dual teaching of both the New Translation Schools—Anuttara Yogatantra or

Highest Yoga Tantra with its Essence Mahamudra practice—and the Old Translation School’s Dzogchen do come to the same essential point. The substance of all these paths comes down to the fundamental innate mind of clear light. Even the sutras . . . have this same fundamental mind as the basis of their thought in their discussion of the Buddha nature, although the full mode of its practice is not described as it is in the systems of Highest Yoga Tantra. - H.H. The Dalai Lama (1984)

How then, do the highest tantric teachings of the ancient school’s Dzogchen, and of the New Translation School’s Essence Mahamudra differ from the sutra view of the Middle Way of Nagarjuna and Chandrakirti, and how are they the same? Is there an essential difference between Buddhist sutra and tantra? Between tantra and Ati Dzogchen? For these answers we must first look to the Buddha’s Three Turnings of the Wheel of the Dharma. The Triyana: three turnings of the Wheel of Dharma are one path. Shakyamuni (Gautama Siddhartha) the historical Buddha (circa 566-486 B.C.E.) transmitted exoteric/outer, esoteric/inner, and highest nondual or greater esoteric (“innermost secret”) teaching for followers and disciples of different levels of understanding. The

mahasiddhas of our great Perennial Wisdom Tradition have generally taught in this exoteric/esoteric “two ways at once.” The teachings of the Buddha are usually classified into The Three Vehicles (yanas) of Enlightenment—The Triyana. These “Three Turnings” present one dharma or one path with differing views. We need the “right view” for our present lifestage understanding. On the accord of the Mahayana, the Three Turnings of the Dharmachakra—broadly

construed—represent the Buddha's teaching on 1) the Four Noble Truths and The Eightfold Path of the Foundational Vehicle; 2) The Mayayana emptiness and Buddha Nature; 3) The Vajrayana Vehicle. Thus the Three Vehicles include the Foundational Vehicle or the Hinayana (Sautrantika and Vaibhashika tenet systems) of the Pali School that flourishes today in Southeast Asia alongside the Theravada, and throughout the world in Shojo Zen of both the Soto and

Rinzai schools; the Mahayana or Great Vehicle (the Causal Vehicle of the Bodhisattvas or Bodhisattvayana) of India, China and Japan (Daijo and non-dual Saijojo zen), and includes the Emptiness of Madhyamaka and the Buddha Nature of the Yogachara (Chittamatra/Mind Only) tenet systems; and finally the Vajrayana or Diamond Vehicle, the Tibetan translation and transmission of the Mahayana. This is Buddha’s third turning of the Wheel of the Dharma. It includes the subtlest tantric teachings, Dzogchen and Essence Mahamudra. The Foundational, so called Hinayana holds that there is only one turning of the Wheel of Dharma. The old Nyingma School classifies these same teachings of the Buddha into the Nine Vehicles of Enlightenment. The first three are the Shravakayana (listeners or disciples), the Pratyekayana or the vehicle of the Pratyekabuddhas (the Way of Solitary Awakening), and the Mahayana or Great Vehicle. These three vehicles comprise the Sutra Tradition or the Outer Vehicle. The Inner Vehicle or Tantric Tradition is classified into three Outer Tantras (Kriya Tantra, Carya Tantra and Yoga Tantra), and the development (creation) and completion stages of the three Inner Tantras (Mahayoga, Anuyoga, and theAtiyoga of Dzogchen). Dzogchen, the Great Completion is the great completion and perfection lifestage wisdom teaching that transcends yet includes

all of the teachings of the previous vehicles. “There is a refinement of understanding that becomes progressively more subtle through the vehicles” (Tulku Urgyen), culminating in the highest nondual teachings of both Old and New Translation Schools—Dzogchen, and Highest Yoga Tantra (Essence Mahamudra) respectively. It is sometimes said that the Buddha taught many contradictory doctrines. But it is not so. Although interpretations will differ and texts

may be deconstructed, we must remember that through all the vehicles the skillful means (upaya) of the Buddha’s teaching varies in subtlety and depth according to the capacity of his listeners. “In order to lead living beings to understanding I taught all the different yanas…” (Shakyamuni, the Buddha, Lankavatara Sutra). In the First Turning of the Wheel of the Dharma, in the Deer Park at Sarnath, the Buddha taught on karma, and the Four Noble Truths

that are the interdependent unity of samsara and nirvana. Here he taught the great truth of “no-self” (anatman, rangtong, emptiness of self), the deconstruction of self or ego-I that is the foundation of all that was to come. It is this great truth of anatman that gradually deconstructs our attachment to the sense of self, and to its impermanent world of phenomena (shentong, emptiness of other).

All the evil, fear and suffering of this world is the result of attachment to the self. - Shantideva

These primary teachings comprise the Hinayana, the “Common Vehicle” of the “listeners.”

In the Second Turning of the Wheel, at Rajagriha on Vulture Peak, the Buddha taught the Great Vehicle, the Mahayana, the subtler truth of the Great Emptiness (Mahashunyata), the Great Compassion (Mahakaruna)—ultimate bodhicitta and the relative bodhicitta that flows from it—and the Three Buddha Bodies

that are the unity of the Trikaya (nirmanakaya, sambhogakaya, dharmakaya). It is the development of bodhicitta—the wish and the action that promotes the liberation from suffering for all sentient beings that is the defining motivation of the Mahayana path. And all this is embodied in the Prajnaparamita Sutra of Transcendent Wisdom—the perfection of the transcendent wisdom that is the ultimate realization of emptiness that is the realization of no-self,

and the final cessation of suffering (nirvana). Here we discover the prior unity of the “Two Truths” (denpa nyis)—ultimate and relative, definitive and provisional—the Middle Way between the extreme views of existence (both relative and eternal, i.e. eternalism), and non-existence (solipsism, atheism, i.e. nihilism). Thus in the Heart Sutra we hear: “Form is emptiness; emptiness is also form. Emptiness is no other than form; form is no other than emptiness.”

It is this great transcendent wisdom that is “the mother of the four noble beings”: the Arhats of the Shravakayana, the Pratyekabuddha Arhats, the Bodhisattvas and the Buddhas. On the accord of the Vajrayana, on his final and subtlest, deepest teaching, the Third Turning of the Dharma chakra, the Buddha revealed that all beings are inherently endowed with “Buddha Nature” (tathagatagarbha), the indwelling capacity for the realization or enlightenment

(bodhi) that is, paradoxically, always already present—the heartseed of perfect presence within the spiritual heart of every being. It is this perfect primordial purity, utterly undefiled by any thought or action, that is our natural, original state of buddhahood, the fundamental nature of mind. And from the direct experience of this luminous awareness flows his supreme teaching that emptiness is not merely a negation of phenomenal reality, but that the

“nature of mind is clear light.” Now this is the Vajrayana or Fruitional Vehicle—the path to ultimate realization and fruition of the prior unity of the provisional and definitive meanings of the Two Truths and the Three Buddha Bodies of the highest non-dual tantras of the Great Mahayana Vehicle. . . Therefore, the ultimate nature of mind is not mere emptiness, but “the nature of mind is the unity of awareness and emptiness.” This prior unity is the

vast expanse of undifferentiated, luminous primordial awareness, the boundless luminosity of the clear light that is completely free of any fabricated object through or emotion. Thus, just as the vast expanse of sky cannot be obstructed by storm clouds, so our stainless primordial Buddha nature cannot be tainted by such adventitious phenomena. It is from this essential, perfectly subjective emptiness base (gzhi), this Supreme Source (kunjed gylpo) in whom all objective and subjective phenomena arise and participate.

One Ground, Two Truths, Three Bodies

Emptiness of mind is not a state of mind, but the original essence of mind…our original mind that includes everything within itself. -Suzuki Roshi

What then, shall we do with this precious life we’ve been given? The main point of all the vehicles of the Buddhist Path is the implicit or express wisdom

teaching of the prior unity of the Great Emptiness (mahashunyata), The Great Compassion (mahakaruna) and our inherent Buddha nature. As we have seen, the essential nature of all dependently arisen phenomenal physical and mental appearance is the vast expanse of the Great Emptiness. And this emptiness is not in any way separate from Ultimate Compassion. Thus, from this great wisdom understanding and experience of emptiness spontaneously arises everyday

lifeworld relative compassion for all unenlightened beings, and relative devotion to the master, but also to all enlightened beings (vidyadhara/rigzin) of the three times (past, present, future). Then, this compassion and devotion enhance understanding of luminous emptiness. The practice of the spiritual path includes and develops both this wisdom of ultimate emptiness, and the purifying intention and motivation of relative compassiondevotion that arises

therefrom. Our Perennial Wisdom Tradition knows this unity of basic space (Emptiness, Tao) and compassion as the Wisdom of Kindness (karuna, ahimsa, hesed/charis). All the masters have taught it. Without this view and action, spiritual practice becomes some species of spiritual materialism. Through this view and practice lies our purpose, the cause of ultimate happiness. Compassion is the “mind of enlightenment”—the loving intention, in thought and

conduct, of bodhicitta—the great “mind of light” of a buddha. “The practice of unification of emptiness and compassion is the basis of the path” (Jamgön Kongtrül, Lamrim Yeshe Nyingpo). “The true path of the Buddhas is the unity of means (upaya) and knowledge (prajna)” (Tulku Urgyen, Repeating the Words of the Buddha, 1996). Enlightenment, our ultimate happiness, rests in step-by-step compassionate activity (Apramana, The Four Immeasurables or Four Boundless

States), the relative-conventional means or method that is the expression in action of the spontaneous lived wisdom (prajna/sherab) that realizes (jnana/yeshe) the Great Emptiness (Mahashunyata) of Madhyamaka. And this emptiness is none other than the buddha nature of Yogachara. According to the Dalai Lama, there is no essential difference between these “two wisdoms”—between emptiness (shunyata), and buddha nature (tathagatagarbha). "Realizing

emptiness we realize our buddha nature. Realizing our innate buddha nature, we realize emptiness." The great teaching of no-self (anatman), impermanence (anitya) and interdependent arising (pratitya samutpada) are unified in these two wisdoms. Such is the prior unity of Buddha’s Three Turnings of the Wheel of the Dharma. So our perceptually imputed and conceptually and emotionally designated provisional meaning, the spacetime reality of the relative-conventional empirical truths (samvriti satya) of phenomenal reality arise from the emptiness of the luminous Ground or Source—

empirically—but are not ultimately findable under scientific, philosophical or noetic (mindspirit) epistemological and ontological analysis. Therefore, such spacetime reality is necessarily empty (shunya) of inherent existence or self-nature, even though such arising phenomena are undeniably “real” by our

intersubjective and interobjective conventional agreement (Chapter I). Indeed, twenty-five hundred years of our Great Perennial Wisdom’s intertheoretical, metaphysical and scientific analytic scrutiny—in both West and East—has revealed absolutely no permanent, independently existing phenomenal particulars or things—no enduring or eternal concrete physical or mental objects, selves, or souls (present company excluded, of course). Postmodern, postclassical

scientific theory—the varieties of the quantum theory—is essentially in agreement with this view. Yeshe Tsogyal, the great female Buddha expresses it definitively: Since life is conditioned by time, it has no permanence. Since objects of the senses are but relative perceptions, they have no ultimate existence. Since the spiritual path is filled with delusion, it has no essential reality. Since the ground of everything is ultimately non-dual, it has no

solidity. Since mind is only thinking, it has no basis or ground. Therefore, I find no thing that ultimately exists. - Yeshe Tsogyal If no thing ultimately exists, and if all objective and subjective phenomena are ultimately “unfindable,” we must ask, how is it that they appear to exist. The question is not whether they exist but how they exist. They exist, but not in the manner in which we perceive them. They lack any discrete, intrinsic reality. This absence, or emptiness, of inherent existence is their ultimate nature. . . It is critical to understand that Madhyamika does not say that things are absent of inherent existence mainly because they cannot be found when sought through critical analysis. This is not the full argument. Things and events are said to be absent of inherent or intrinsic existence because they exist only in dependence on other factors. . . In other words, anything

that depends on other factors is devoid of its own independent nature, and this absence of an independent nature is emptiness. . . Nagarjuna says that things and events, which are dependently originated, are empty, and thus are also dependently designated. . . [He] concludes there is nothing that is not empty, for there is nothing that is not dependently originated. Here we see the equation between dependent origination and emptiness. . . the path of the Middle Way, which transcends the extremes of absolutism and nihilism. - H.H. the Dalai Lama, Buddhadharma, Winter 2004, p.20

The true and ultimate nature and source of all relative empirical appearance therefore, is pregnant luminous emptiness (not void, empty nothingness), Ultimate or Absolute Truth (paramartha satya), the definitive meaning that is the “ultimate mode of existing of everything”— Tathata or Dharmata. Astonishingly, this luminous emptiness is intrinsically aware! And therein lives the cognition/awareness/consciousness that all sentient beings participate

in, whether or not they realize it. And this is our immediate potential for enlightenment—Buddha Nature, Christ Nature, Tao, Zen, Brahman—inherent within all self-aware beings. Tat tvam asi. That we are! Moreover, we may utilize the Sutrayana discriminating wisdom (sherab/prajna/sophia) of relative empirical truth as method (upaya) to recognize, then realize the tantrayana non-dual transcendent Primordial Awareness Wisdom (yeshe/jnana/gnosis) that is Ultimate Truth. Upaya is Ultimate Truth acting wisely, skillfully and compassionately in the everyday world of spacetime relative-conventional truth. It is this

Middle Way teaching of the unity of these Two Truths of the Buddha that extends through all the vehicles of the Dharmachakra. But, according to His Holiness the Dalai Lama, these vehicles (yanas) differ as to the subtlety or depth of their views and meditation on emptiness, on the clear light, and on the altruistic intention of bodhicitta. So the views of emptiness in sutra and tantra are the same, and they are different. How is this apparent contradiction resolved? Emptiness, Objective and Subjective. Let us now consider the Tantrayana distinction between objective and subjective emptiness. So

from the point of view of objective emptiness we can say that there is no difference between sutra and tantra with regard to the view of emptiness. However, from the view of subjective experience there is a difference in the understanding or view of emptiness between sutra and tantra. - H.H. The Dalai Lama (Dzogchen, 2000)

His Holiness teaches that the contemplative view and practice of meditation on the intrinsic emptiness of existence of appearing phenomena is essentially the same in the first six of the nine Nyingma vehicles, that is, the three sutra vehicles and the first three or outer tantric vehicles. These are the

vehicles that are founded upon the Middle Way of Nagarjuna and Chandrakirti, as we have seen. Likewise, in the final three tantric vehicles—the inner tantras of Nyingma including Dzogchen and its Ati Yoga and the Anuttara yoga/Highest Yoga Tantra (Essence Mahamudra) of the new translation tantra schools—the levels of subtlety or depth regarding emptiness as the intentional object of meditation are again the same. This is the view of “objective emptiness,”

the objective clear light (“objective luminosity”), “the emptiness which is the object of a wisdom consciousness.” Here, emptiness is viewed as a negation of phenomenal existence, and therefore of an ontologically independent perceiving self. Here, emptiness is a “non-affirming negative phenomenon,” and is not replaced with anything positive, affirming, more inclusive or transcendent. However, from the view of “subjective emptiness” (nay lug), the subjective experience of clear light mind (“subjective luminosity”) which is the more subtle wisdom consciousness of

primordial Basic Mind Itself, there is a considerable difference in view between these highest tantras—Dzogchen and Essence Mahamudra on the one hand—and the less subtle tantra and sutra vehicles on the other. As we will see, Mahashunyata, the Buddha’s Great Emptiness is not ultimately a non-affirming negative. In the highest or subtlest view, the negated phenomena appearing to a self as relative-conventional reality is replaced by the affirming

luminosity of the clear light (‘od gsal/ösel/özer/prabhasvara), the selfless, egoless positive pure bright clarity of the emptiness of form. “Form is emptiness; emptiness is form” (from Buddha’s Heart Sutra). Indeed, from the very beginning, there is no enduring permanent reality or self to negate! As we have seen, there are only these perceptually and conceptually designated relative- conventional truths of arising phenomenal appearance. So there emerges a

subtle, outshining luminosity as the Great Emptiness manifests itself from the primordial purity (kadag) of the Base or Ground (gzhi) as mere appearance of arising physical and mental forms—apparent, relative-conventionally perceived and imputed spacetime phenomenal reality. This brightness or radiance is then, the ultimate nature of Reality Itself (cho nyid), the clearlight Nature of Mind (sems nyid). But we are cautioned throughout the teaching that this

essential Nature of Mind is not an ego-self, nor is it a “Higher Self,” eternal soul or theistic creator God. Nor is this luminous continuity of Basic Mind Essence some separate thing—something “other.” Such relative-conventional dualism—attachment to appearing phenomena, attachment to our beliefs about mind-created God or gods, and attachment to our experiencing separate egoic self-sense—belies the Ultimate or Absolute Truth of the prior unity of the Two Truths that is singular Basic Mind Nature. So the two truths are in actuality this one great truth (paramartha satya)—our Basis or Supreme Source—ultimate mode of everything that appears, realized, step-by-step through the confusion of the spiritual path. Yet, paradoxically, this Absolute Truth, the ultimate Great Emptiness, is not itself an independently existing Absolute Truth. According to His Holiness, it too is subject to the prior causes and conditions of

previous universes and kalpas, that is, it too is subject to the natural law of dependent arising (pratitya samutpada). This is, from the view of conceptual, relative truth, the ultimate paradox of the “emptiness of emptiness.” However, from the non-dual view of Absolute Truth there is no dilemma, no problem, no conceptual thinking whatsoever. Do you understand the two minds: the mind which includes everything, and the mind that is related to something? - Suzuki Roshi

Hence, there is a profound difference between the direct and immediate actuality of the transcendent wisdom of natural emptiness (essential rigpa), and indirect, mind-made perceptual-conceptual emptiness. So here, in the non-dual view of subjective emptiness of the deepest or highest tantras of both the

old and the new tantra schools, the development stage Middle Way of the Madhyamikas of the Svatantrika and Prasangika Schools develops or yields to the deeper, subtler or more direct understanding that dialectically transcends, yet pervades and includes it. Here, in highest stage innermost secret Ati yoga, and Essence Mahamudra, emptiness meditation is an “affirming negative” in which the actuality—not an indirect concept and

not a direct experience (nyam)—of clear light mind appears directly to the yogin/yogini, yet is “known to be empty of inherent existence.” This then, is the essential difference between the Madhyamaka of sutra and lower tantra vis-à-vis the highest non-dual tantras with regard to the view of emptiness. . .

Relationship: Big Mind, Small Mind, and the Bridge. Can this direct, greater esoteric or non-dual (advaya, gnyis med, “not one, not two”) teaching of the innermost secret, highest tantras be reduced to the understanding of the less direct, lesser esoteric or even exoteric view and practice of the less subtle teaching of sutra or lower tantra, as Evans-Wentz, Jung and many other non-practitioner scholars have done? No. Throughout Buddhism, and indeed throughout

our great Perennial Wisdom Tradition, the exoteric outer and lesser esoteric inner view cannot accomplish the greater esoteric, innermost or non-dual realization, despite protests of the pathologically independent, facile egalitarian, antiheirarchial postmodern ego-I. Under sway of the ignorance (avidya) of this separate egoic self-sense we become the fearful, hopeful advocates of the developmental limits of our present lifestage with its uncomfortable

“comfort zones,” arguing and defending the painful result. As we have seen, cross-cultural psychospiritual development (spiritual evolution), our relative-conventional growth through culturally universal sequential lifestages and mindstates of the body-mind-spirit (gross, subtle, causal and non-dual) continuum of consciousness, is invariant and state-specific. Lifestages and their accompanying mindstates presuppose earlier, less subtle emotional,

phenomenological stages or levels of consciousness development (Appendix A). Although stages overlap, and unfinished psychoemotional business must be revisited and interpretively unpacked, lifestages cannot be skipped. While the wisdom understanding of the subtler, deeper or “higher” lifestages subsumes, includes and transcends the earlier, less subtle lifestages, the understanding of the latter cannot grasp, accomplish or realize the former. Of course

there are surface differences—relative-conventional perception, concept and belief—in the structural constitution of developmental lifestages across sociocultural space and time. But the deeper, subtler mental-emotional-spiritual structures are the same. And the surface understanding cannot comprehend the depth. For example, in the East/West stage model of our cognitive continuum of psychospiritual development, culturally conditioned relative-

conventional symbols (language) emerge before concepts, which emerge before rules and morality, which necessarily precede exoteric (outer) religious belief, and then esoteric (inner), and finally greater esoteric (non-dual or innermost/secret) subtle spiritual mindstates and lifestages (Appendix A). The surface conceptual and belief systems and deity icons differ within the numinous Depth (Bathos), primordial womb that is their singular matrix and

essential ontological structure, the very essence and nature of mind. Just so, this non-dual perfectly subjective, luminous clear light Nature of Mind (purusha/cittata/sem nyid), Suzuki Roshi’s “Big Mind,” the ultimate or “definitive meaning” of our Supreme Source subsumes pervades and embraces, yet transcends all of the dualities of conditional existence, the relative-conventional limits of the “provisional meaning” of physical and mental experience that is the dependently arisen subjective content and objective production

of dualistic “small mind” (prakriti/citta/sem). Again, conceptual small mind cannot grasp or realize Tao, the Great Emptiness that is Big Mind, although paradoxically, the “pure presence” of it is “always, already” present at the spiritual heart of each individual being. And it is the confusion of the spiritual path that is the bridge to the resolution of this paradox, and ultimately, the realization of this great truth. “Just as the steps of a

staircase, you should train step-bystep. . . steadily to the end” (Shakyamuni, the Buddha). His Holiness teaches that dependent arising or dependent origination (pratitya samutpada) of conventional reality is the “natural law” that all arising phenomena are “dependent upon their causes in connection with their particular conditions.” Without this natural, uncreated interrelationship—this contexual, interdependent and coincident aggregation of causes

and conditions—such appearing physical and mental phenomena could not, logically or empirically, arise and exist in any way at all. If we can understand that all perception and all seeing is the great truth of dependent arising, then we can understand emptiness . . . the true Nature of Reality. Why? Because dependent arising is Reality Itself. . . Emptiness and compassion must be unified. . . So develop both compassion and an understanding of emptiness. —Ad

zom Rinpoche (Upaya Zen Center Retreat, Santa Fe, NM, 2002) In the Prasannapada, Chandrakirti’s great commentary on Nagarjuna’s Exposition of the Middle Way, we learn of this natural, unseparate interrelationship of emptiness and dependent origination, and the Buddha’s Four Noble Truths. Chandrakirti reasons that, if we will first postulate the interrelated prior unity

of emptiness and its arising interdependent phenomenal appearances (“form is emptiness, emptiness is form”), we can then postulate the causal connection, the cause and effect relationship, between the first two noble truths—the Truth of Suffering and the Truth of the Cause or Origin of Suffering. This causal connection is the natural law of karma—thought, intention, action and effect (positive and negative imprints). Karma is an example, in behavioral terms

(conduct or ethics), of the general scientific law of causality that governs the realm of relative-conventional spacetime reality. Thus, from ignorance (avidya) arises concept mind (manovijnana), the egoic negative afflictive emotions—fear, anger, greed and pride—and attachment to the self (kleshamind/klishtamanovijnana) that results in the mental and emotional imbalances that produce the destructive behavior that causes suffering. The

positive emotions of tantric Buddhism’s Four Boundless States (The Four Immeasurables), our Perennial Wisdom’s Great Love—kindness, compassion, joy and equanimity—result in mental and emotional balance that produces the behavior that causes happiness. It’s so very natural and logical, so lawful. We reap what we sow. What we give is what we get. What goes around, comes around. “What you are is what you have been. What you will be is what you do now”

(Shakyamuni, the Buddha). Thus, according to Chandrakirti, from an understanding of these First and Second Noble Truths, we may consider that there may be a possible way to the final cessation of suffering—its cause or origin—a path or bridge to freedom from this ignorance and imbalance

(avidya/marigpa/ajnana) that is the root cause of suffering. Thus follows the Third Noble Truth, the Truth of the Cessation of Suffering. And if this cessation is possible—and by the demonstration of the lives of all the buddhas and mahasiddhas of our Great Perennial Wisdom Tradition, it clearly is

possible—we can then postulate the Fourth Noble Truth, the Eightfold Path that is the precise, objective, scientific mind training program that transforms habitual negative mental, emotional and attentional imbalances into our natural inherent transcendent wisdom, the Prajnaparamita, Great Mother of all the buddhas. This is the great truth that realizes and actualizes our primordial source or ground state, and beyond, to the ultimate perfection of buddhahood,

perfectly awakened state and activity of being in form that is, paradoxically, always present within each one of us from the very beginning. “The child knows its mother.” We shall not cease from exploration And the end of all our exploring Will be to arrive where we started And know the place for the first time. - T.S. Eliot (Four Quartets)

How then, does an ordinary being become a buddha? What did the Buddha have? He had the Four Noble Truths and the Eightfold Path that leads, step-by-step, to the final cessation of suffering (nirvana). What do we have? We have our Refuge in the Three Jewels (Buddha, Dharma, Sangha) that are the Three Roots

(Guru, Deva, Dakini) and the Three Buddha Bodies (the three kayas). That is, we have—here and now—our Buddha Nature, mirrored by the spiritual mentor or Vajra Master; then we have the great teaching of the Buddhadharma and the intervention of mantra and the deities; and we have the Sangha, our spiritual community that also includes our spiritual lineage and all the enlightened ones—the vidyadhara/rigzin of the three times—past, present and future. Thus, we

have always this Relationship, and the bridge that is the path of all the buddhas continuously revealing the prior and ever present unity of these precious Three Jewels. So we take Refuge in the Three Jewels, the Three Roots, and the Trikaya of the Base, and begin to develop the great intention to the compassionate heartmind that is bodhicitta, for the sake of all beings. In Tibetan Buddhism we accomplish this through ngöndro, the foundational practices

that are the prelude to the Dzogchen or to the Essence Mahamudra transmission. Then, the point of practice of the Mahayana path is recognition, then realization of this prior ultimate unity of emptiness and compassion, and thereby the gradual integration of that into our lifeworld of relative-conventional thought, intention and action. This is the integration of View and Conduct, integration of Ultimate Truth with Relative Truth, integration of

the Ground with the Fruit or Result, integration of nirvana and samsara—step-by-step, even though to the fearless warrior-yogi of “uncontrived wisdom conduct” such an integration has never left the prior unity of the perfect sphere of Dharmakaya. Herein arises the most unusual paradox of the most subtle paths of Dzogchen, and of Highest Yoga Tantra. . . The Paradox of the Path: Integrating View and Conduct. So gradually, through the practice of the path, the veils of ignorance (maya) to the great truth are lifted and the under

standing of the unity of emptiness and compassion is increased. Then, wonder of wonders, peaceful instant of emptiness equanimity, mindful non-conceptual recognition that is rigpa, “pure presence” of uncreated ineffable Basic Mind Essence. Here, the prior unity of method (upaya/function) and wisdom

(prajna/structure), of all development and completion lifestages (Mahayoga, Anuyoga and Atiyoga), mindstates, yanas and wisdoms are, just for this interior moment now (turiya), nakedly seen and known (penetrating insight) as Dharmakaya, utterly free of fear and hope, free of the duality of all emotional affliction and conceptual elaboration. “Who are you in the space between two thoughts?” In this non-dual “state of presence” egoattachment or clinging,

fear and anger “self liberate” at the very instant of their arising. Like a bird in the vast empty sky, thought and action leave “no trace.” Thoughts and appearances rise up from the great ocean of luminous clarity, then return again to this source without any change in essence. When one realizes that the actual nature of thinking and emotion is luminous clarity, there is no need to avoid thoughts, concepts and emotions. There is no need to believe that

which we think, nor to defend that which we believe. “The Nature of Mind is Buddha from the beginning.” This is the view (sho shin) and fruition of Ultimate Truth. But it’s all just very ordinary—“nothing special” (wu shin). It appears special and dramatic only when viewed egoically, from the outer exoteric condition of the prideful, egoic, self-reified truths of relative-conventional reality. So it is the ascending development stage of the path— devotion to the master, ordinary, repetitive everyday compassionate living, and the surrender or “letting go” that is renunciate practice—that transforms such extraordinary, special but temporary samadhi “states” into the permanent lifeworld “altered traits” of the meditative stabilization of completion stage realization, and compassionate lifeworld actualization. Then finally, in due course and by grace, there manifests the later bhumis, and the perfection of Buddhahood. “Descend with the view while ascending with the conduct. It is most essential to practice these two as a unity” (Padmasambhava). We must then, engage the “paradox of the path” that is the paradox of seeking—the effortful foundational practices of the Buddha’s teaching—while standing firmly in effortless view and conduct of the highest non-dual tantras. This is the Buddha’s great teaching in “two ways at once.” Thus, through skillful

effort (upaya), while “letting it be as it is”—in due course and by grace of the master—we exhaust the seeking strategies of the Great Search and awaken to our already present perfect happiness, the buddha nature within each sentient form. Here, our question posed above, the apparent contradiction between the two truths of the renunciate ascending view and conduct of the Sutrayana Theravadins, and the descending view and compassionate conduct of the Mahayana and

Tantrayana bodhisattva ideal is resolved in non-dual clarity, the prior perfection of this primordial “state of presence,” the three buddhakaya dimensions resolved and unified in pure presence of the “essential rigpa” of Dharmakaya (Svabhavakakaya). This great non-dual truth of the descent and ascent of Spirit through form is told again and again throughout the subtlest “innermost secret” teachings of our perennial Great Tradition. This is “the light of the Tao that is beyond heaven and earth,” the very “Gnosis of Light

that lighteth every one that cometh into the world.” This is Kham Brahm—“All is Brahman”— “The Bright” of the old Vedas, Upanishads, and Vedanta. In Sutra this view is Uma, Ultimate Truth, the final third truth of T’ein T’ai’s non-dual “Middle Way Buddha Nature” (Chih-i), beyond the duality of permanent, eternal existence, and nihilistic non-existence. In Dzogchen this practice is “swooping down from above (with the ideal of the view) while climbing up from

below (through the struggle of the conduct).” Padmasambhava advises, “Keep the view as high as the sky, and your deeds as fine as barley flower.” Yet here, Guru Rinpoche cautions us not to “lose the view in the conduct,” and not to lose “the conduct in the view.” We must not lose the View of Absolute Truth—The Great Emptiness—in the dualistic ignorance of the hope and fear of conceptual relative-conventional truths and the ethical conundrums of right and wrong

conduct. Just so, we must not lose the relative truths of ethical conduct—valuation, deciding on kindness while rejecting unkindness—for a political, idealized, but unrealized view of the Great Perfection of non-dual Ultimate Truth. If you lose the view in the conduct, you will never have the opportunity to be free. If you lose the conduct in the view, then you ignore the difference between good and evil . . . you stray into black diffusion. - Tulku Urgyen,

At It Is, 2000) So we just continue the compassionate ethical conduct of our relative-conventional spiritual practice, in the midst of the continuous error (shushaku

jushaku) of hope and fear, of accepting and rejecting, while making a constant mindful effort to keep the View that is utterly free of this dualistic bias—perfectly free of the three emotional poisons of ignorance, desire and anger—that mindless continuous cycle of “black diffusion” of one without a greater

view. This is the great Middle Way view that is the precursor to the nondual realization of a buddha, the “pure view” that lives, sleepwaiting at the heart of each one of us as we tread our chosen path. What a marvelous paradox! In order to integrate the two truths of View and Conduct we must distinguish the

duality of their relative difference—so that we don’t lose one in the other—while yet abiding in the continuous non-dual awareness of their prior essential unity. Step-by-step, by the grace of the spiritual master, of course. This then, is the perfect practice of the integration of view and conduct, wisdom and

merit, the prior unity of the Two Truths—ultimate and relative—that is both origin and aim of the activity or behavior (ethics) of the ascending and the descending aspects of refuge in the Three Jewels of the Buddhist Path, and indeed, of all the “greater esoteric” or non-dual innermost secret spiritual

paths of our entire great Perennial Wisdom Tradition. This unity is and has always been, “already accomplished,” nothing special, ever present and never absent from our inherent happiness, right here and now, radiating its light to all beings in the very midst of the dark night of this confusion of our

chosen lifeworld path. Wondrous paradox indeed! The Big Picture and the Middle Way. According to His Holiness the Dalai Lama, the innate clear light nature of mind, infinite, ineffable singularity of unmanifest luminosity of the primordial Ground or Base (gzhi ‘i ‘od gsal)—Buddha Nature—may be viewed from two levels

of subtlety of understanding, sutra and tantra. Sutrayana understanding is, as we have seen, the “objective clear light.” Tantrayana, especially Anuttara Yogatantra (Highest Yoga Tantra) and Dzogchen understanding is, according to His Holiness, the subjective experience of clear light (nay lug) that is the non-dual primordial awareness of the essential clarity of Mind Nature (sem nyid), or Basic Clearlight Mind. This naked awareness (rigpa jenpa) of

“fundamental innate clear light mind” is the essential, “ultimate root of consciousness,” the Ultimate Truth and definitive meaning of Reality Itself. This luminous “affirming negative” of clear light mind is the basis and essential or ultimate way of abiding for the meditator on emptiness. Here we have the ultimate solution to that really “hard problem” of the essential nature of consciousness itself, the realization and actualization of the ultimate Nature of Mind, Happiness Itself. As we have seen, in actuality this primordial Transcendent Wisdom dialectically subsumes and transcends not only the objective understanding of the less subtle teaching on emptiness, but even its direct subjective yogic experience, for such wisdom is utterly non-dual (“not two, not one,” “two in one,” neti, neti/not this, not that). This resplendent clear light awareness is, for the yogin/yogini, “essential rigpa” (paravidya)—prior

unity of appearance and emptiness, of clarity/luminosity and emptiness, of bliss and emptiness, of awareness and emptiness (the four wangs or empowerments) of development, completion and perfection lifestages of the path—just for the singularity of this timeless eternal moment now, moment to moment (“brief moments many times”) in perfect unbroken symmetry of all-embracing primordial awareness continuum of all that is. Rigpa then, is not a concept (thought) or

an experience (nyam), but the apriori, bright naked presence of the transcendent Primordial Awareness Wisdom (yeshe/jnana), Prajnaparamita—Divine Wisdom Mother of all the buddhas—prior to mindcreated thought, explanation, emotion and experience. So the transcendent unity of clearlight mind has its objective and subjective aspects. The former is the “object emptiness” (lhundrub/presence) that is always already united with the latter, the subjective aspect of

clear light (kadag/purity), Dharmakaya (chö ku), the Ultimate Reality (chö nyid). This Reality is the Absolute Truth (don dam denpa, paramartha) that is the “all empty” non-dual Ground or Emanation Base (gzhi), our Great Wisdom Mother (Yeshe), primordial womb of all the descending subtle and gross appearing phenomena of the relative truths of Sambhogakaya and Nirmanakaya. “Form is emptiness; emptiness is form.” There is no emptiness other than form. There is

no form that is not an emptiness. Yet emptiness and form are not separate “things,” as we have seen. They are utterly interdependent, a prior perfectly subjective unity. “This is the Buddha’s great truth of dependent arising—the final view that is free of the duality of the extremes of absolute permanent existence, or the nihilism of non-existence. . .” (Adzom Rinpoche, 2002). The future is entirely dependent upon what is occurring now. “What you are is

what you have been. What you will be is what you do now” (Shakyamuni, the Buddha). This great truth is the basis of our Perennial Wisdom’s natural law of cause and effect—karma—our behavior and conduct, the way we must live to be happy in this mad, mad world. Phenomena appear dualistically, as pure or impure, but their energy essence and basis or source—their actual nature—is always radiant non-dual emptiness, ever free of all the perceptual imputation, conceptual designation, and the emotional hope and

fear of “small mind.” “There is nothing other than this.” This then, is the radically postcritical, postmetaphysical great truth of Uma, the Middle Way—beyond dualistic conceptual judgment, beyond crazy or sane, beyond good and evil, utterly “gone beyond” (paragate) all concept, belief, deity, icon and

archetype. Of course, we must evaluate—polarize/dualize—to live in the realm of empirical, relative-conventional spacetime reality. As we have seen, ethical conduct requires that we discriminate between good and evil, between unifying pure view, and separative false views, between kind intention and action, and harmful destructive thought and action. Yet, there is this great primordial transcendent View—the big picture “as high as the sky”—abiding in

perfection of the non-dual Middle, always in the timeless fourth time (turiya), deep in the heart of this very moment Now, at the spiritual heart of every being. . The Triune Nature. In the classical tantric metaphor, this perfectly subjective sourceground or base (gzhi) is like the infinite expanse of cloudless sky. Rigpa is like the sun, the sky’s vast capacity for the perfect clarity of awareness. The descending light/energy/motion of this infinite

awareness continuum is like the sun’s rays (‘od gsal), transcendent Primordial Awareness Wisdom (yeshe, jnana, gnosis) penetrating and illuminating the dark clouds of ignorance (avidya/marigpa) that obscure the actual nature of Mind. These three manifest as the five rays or five colors of the great mandala of the five Buddha families, dependently arisen phenomena emerging as the five aggregates or skandas of relative-conventional, empirical spacetime reality.

These three—sky, sun and rays—are respectively, Dharmakaya, Sambhogakaya and Nirmanakaya; the Three Vajras of Body, Voice, and Mind; Om, Âh, Hum. These three buddha bodies are the inseparable, unborn Trikaya of the Base, Absolute Bodhicitta, Svabhavakakaya—The Fourth Body—prior unity of the Vast Expanse of this infinite consciousness continuum that is primordial Mind Nature Itself (sem nyid). This unified Trikaya of the Base is the perfectly subjective deep background continuum that is unobstructed Pure Alaya (amala-vijnana), the ninth consciousness revealed in the highest tantras. Its luminous presence is the buddha nature heartseed of all the tathagatas, all the buddhas of the three times—past, present and future—transcending yet pervading our waking, dreaming and deep sleep states through this timeless moment now, primordial abode of the fourth time (turiya). “The three times are one. . . Now is the time to

enter into it” (Garab Dorje). Therefore, from the view of relative-conventional truth, these three kayas or bodies are the three aspects of the great Perennial Wisdom Truth of our unseparate participation and growth through exoteric (course/outer/waking state), esoteric (subtle/inner/dream state), and ultimately, the non-dual greater esoteric (very subtle/innermost secret/deep sleep state) developmental lifestages—all the way to the end of it—Buddhahood.

(Appendix A: The Seven Stages of Life and the Dimensions of Consciousness: A Perennial Wisdom Topology of Spirit) However, from the view of absolute or ultimate truth, the view of a buddha, all of this is merely the playful display of the prior infinite unity of Dharmakaya, utterly “gone beyond” sentient perception, concept, belief, archetype and all negative afflicted emotion. The stages of the path and the Transcendent Wisdom revealed and grounded therein is perfectly expressed in Sutra in the great Prajnaparamita Mantra: Om, Gate, Gate, Paragate, Parasamgate, Bodhi Svaha

(from the Heart Sutra), and in Tantra in the Great Mantra of Avalokiteshvara: Om Mani Padme Hum (Hrih). Perhaps the most profound of Tibetan Buddhist mantras for the practitioner on the path is the Vajra Guru Mantra: Om Ah Hum Bendzra Guru Pema Siddhi Hum. It is said that the twelve syllables of this mantra bestow the complete blessing of the Buddha’s twelve kinds of teaching that entirely purifies the negative emotional obstructions of the twelve links of dependent arising on the Wheel of Becoming! It furthers one to practice these mantras. . . Such an Orphic, participatory epistemology and ontology has been called, in the gloss of the emerging noetic (mind-spirit) New Reformation view, the “wholeness principle”—telos, eros, the movement that connects (growth)—attitudinal view, meditation and action or conduct. This is the path that is the intertheoretical, meditativecontemplative and practical antidote

to thanatos, the destructive “separative principle” embodied as the three emotional poisons: avidya/ignorance that is desire/attachment and anger/aggression. Within the unbroken wholeness of the ultimate Nature of Mind arises the twelve links of mind-generated positive and negative thought and emotion. Ignorance of the essential goodness of this Ground is thanatos—evil—the incessant “black diffusion” that manifests as negative materialist idiom

and ideology of interobjective (social) and intersubjective (cultural) global massmind. Thus all limbs of the Buddha’s teaching have this one purpose—to bring us to the non-dual Transcendent Wisdom. It participates in and pervades all views and paths for one who is capable of accessing it. . . All things flow from emptiness, and return again to emptiness, like the sun and its rays. This is dependent arising. . . the dynamic display of the mind. This is the

ultimate nature of arising phenomena, the Nature of Reality Itself. - Adzom Rinpoche (2002) The Threefold Space. According to recent Dzogchen master Tulku Urgyen Rinpoche, the two innermost principles of Dzogchen are Space (ying/dhatu) and Awareness (rigpa/vidya). This Basic Space is pregnant luminous emptiness, the unity of emptiness and clear luminosity. In the Dzogchen teaching it is often

seen as a threefold unity. Outer ying is like pure vast empty sky, the Great Emptiness (Mahashunyata) in whom arises all phenomena. This is Akashadhatu. Inner ying is the emptiness of Mind Essence, the very Nature of Mind (citatta/sem nyid). This is Vajradhatu. Innermost ying is rigpa, luminous clarity of non-dual recognition, bright knowing awareness of the prior primordial unity of these three. This is Jnanadhatu. In Dzogchen, this innermost realization of

space, of the infinite “Vast Expanse” is klong (long), beyond all judgment and bias, beyond even the subtlest subject-object duality, beyond subjective and objective emptiness, beyond ground and path luminosity. As space pervades, so awareness pervades. . . like space, rigpa is allencompassing. . . Just as beings are all pervaded by space, rigpa pervades the minds of beings . . . Basic space is the absence of mental constructs, while awareness is the knowing of this absence of constructs, recognizing the complete emptiness of mind essence. . . The ultimate dharma is the re

alization of the indivisibility of basic space and awareness [that is] Samantabhadra. - Tulku Urgyen (As It Is, Vol. I, 1999; Rainbow Painting, 1995)

Here is neither samsara nor nirvana, neither self nor other, neither buddhas nor sentient beings. This state is known as primordial purity because it is not stained or obscured by any hint of confusion or dualistic thought; it is the original, pure nature of all existence . . . - Francesca Fremantle, Luminous Emptiness, 2001

“The dharmakaya arises unnecessarily out of infinite space” (Chögyam Trungpa Rinpoche). And the great beauty of it—“It is already accomplished,” here, now, for everyone. Constant human awareness of this great truth precedes the compassionate conduct that lifts the suffering of beings and generates great

happiness in the giver. No Problem. We may now review the three essential yanas of the Buddhist path— sutra, tantra and Dzogchen. According to the Third Dodrupchen, and His Holiness the Dalai Lama, the higher or Inner Tantras of both Anuttarayoga tantra or Highest Yoga Tantra (father, mother and non-dual tantras), and of Ati Dzogchen (semde, longde, mengagde/upadesha teaching series) are essentially non-dual tantras, while the less subtle, less direct outer tantras and sutras of the Triyana remain the more fundamental or foundational vehicles of the Buddha’s transmission to us. And all these vehicles of the path have the same goal—Prajnaparamita—the great primordial Transcendent Wisdom (Jnana/Yeshe), the wisdom of the buddhas. His Holiness reminds us here, that without this foundation of the path, the wisdom temple cannot be built. Thus, for Tibetan Buddhism, the preliminaries or foundational practices

(ngöndro) are actually the most profound. Indeed, they contain and introduce the very highest non-dual teaching of both sutra and tantra. They continue to be fundamental through development, completion and perfection stages of all the Vajrayana paths. The Tibetan Vajrayana or Mantrayana then, contains both Sutrayana and Tantrayana teaching vehicles: the renunciation practices of the sutras, the transformation practices of Outer and Inner Tantras and of non-

dual highest Essence Mahamudra, and the non-dual, “spontaneously self-perfected” (lhundrub) state of Ati Dzogchen. The profound paradox of the Dzogchen view is that there is no afflicted consciousness or emotion that must be renounced, purified or transformed! Indeed, there is no actual reality at all to negate, merely appearances. The Nature of Reality, its very heart-essence, is “perfect from the very beginning,” is “Buddha from the very beginning.” This

prior, inseparable unity of emptiness, luminosity and awareness is blissful primordially pure presence of androgenous Samantabhadra (Vajradhara, Dorje Chang), our Supreme Source, always present throughout the bodymind, ascending and descending upon the breath of mindfulness, indestructible thigle essence deep at the heart. This is the essence of Buddha’s third turning of the wheel of the dharma. Again we understand, this, our bright innermost presence (rigpa/vidya) is our continuous participation in the actual Nature of Mind, the ultimate nature of Reality Itself (chö nyid), just as it is (thamel gyi shepa), utterly trans

cending any thought, concept or even experience of it. Tat tvam asi. We are unseparate from That. When we forget ourselves we are actually the true activity of the big existence, or reality itself. When we realize this fact, there is no problem whatsoever in this world. The purpose of our practice is

to be aware of this fact. . . It may be too perfect for us, just now, because we are so much attached to our own feeling, to our individual existence. . . When you can sit with your whole body and mind, and with the oneness of your mind and body under the control of the universal mind, you can easily attain this kind of right understanding. . . When we reach this understanding we find the true meaning of our life. . . How very glad the water must be to come

back to the original river! - Suzuki Roshi, Zen Mind, Beginner’s Mind, 1970 In this way then, through a non-dual understanding, the two seemingly contradictory theses of the views on emptiness in Sutra and Tantra—objective and subjective, ascending and descending—are dialectically transcended, yet included and embraced in the higher or deeper synthesis of the supreme view and

practice of the subtlest highest tantras, without mistakenly reducing the great non-dual teaching to explanatory experiences and expressions of a profound, yet less subtle understanding. “No problem whatsoever.” Ultimately then, the emptiness of Madhyamaka is the emptiness of Dzogchen and of highest Essence Mahamudra, although the relative-conventional view and practice differs slightly. And the result or fruition of all three is identical—Buddhahood. Again,

this is the Buddha’s perfect teaching in “two ways at once,” the prior “natural unity of one identity with two aspects.” One ground, two truths, three bodies are a prior unity that is apriori Ultimate Truth of our perfect Sourceground, already embodied deep within us. This is the Supreme Source of arising illusion and confusion of relative-conventional reality of the spiritual path, all the way to its ultimate fruition. A most amazing paradox! Each and every

one of us has the potential to realize fruition. It is you yourself, who make the decision . . . Open the door . . . follow the path right to the end. - H.H. The Dalai Lama Ground, Path, Fruit

The Fruit is no different at the pinnacle of enlightenment than it is at the Base. - Ad zom Paylo Rinpoche

Integrating the Ground and the Fruit Through the Path. Therefore, in the Dzogchen View the Fruition—enlightenment or Buddhahood—is always already present in the very nature of our essential Base or Ground (Emptiness/Buddha Nature), but it is not yet realized and actualized through the Body, Voice and Mind of

this nature. The essence of enlightenment— the very heartseed of Buddha Nature “is a continuity that extends throughout our journey along the stages of ground, path and fruition” (Kenchen Thrangu Rinpoche). The precious samaya or covenant between Vajra Master and student facilitates the Dzogchen

development (creation) and completion stages of the path. This is absolutely necessary to integrate and accomplish the prior already perfect unity of ground and fruition in the confusion context of our everyday lifeworld. If this process is to bear the fruit of liberation, the student must continuously

dedicate the merit and benefit of these profound practices, not to the self, but to the benefit and ultimate happiness of all beings, great and small, everywhere. What then, is the Dzogchen method of clarifying the confusion of the path? It is View, Meditation, and Conduct. In Dzogchen, on the basis of

the clear light itself, the way in which the clear light abides is made vivid and certain by the aspect of rigpa or knowing. That is free from any overlay of delusion and from any corrupting effect due to conceptual thoughts, that will inhibit the experience of clear light… It is not accomplished as something

new, as a result of circumstances and conditions, but is present form the very outset... an awareness that can clearly perceive the way in which basic space and wisdom are present. On the basis of that key point, the realization of clear light radiates in splendor, becoming clearer and clearer, like a

hundred million suns. . . Here the aware aspect of clear light or effulgent rigpa (which arises from essential rigpa) is stripped bare and you penetrate further into the depths of clear light . . . even as objects seem to arise . . . It is on the basis of this that you train. - Third Dodrupchen Jigme Tenpe Nyima (quoted in H.H. The Dalai Lama, Dzogchen, 2000.) The Main Point. Dodrupchen teaches that “The main point is that the rigpa taught in the Dzogchen approach and the wisdom of clear light (Anuttarayoga tantra) are one and the same.” Twentieth Century rime (non-sectarian) master Tulku Urgyen agrees. Regarding the “three great views”:

The view of Mahamudra, Dzogchen and Madhyamaka is identical in essence. Although it is said, ‘the ground is Mahamudra, the path is the Middle Way, and the fruition is the Great Perfection,’ in the view itself there is no difference whatsoever. . . The awakened state of Mahamudra doesn’t differ from the awakened state of Dzogchen or Madhyamaka. Buddhahood is the final fruition of all these regardless of which of these paths you follow. - Tulku Urgyen (Rainbow Painting, 1995)

Thus, the awakened state of presence—rigpa—does not differ in Dzogchen, or the Essence Mahamudra of Highest Yoga Tantra, or the highest Madhyamaka of the Definitive Meaning. However, His Holiness, the Dalai Lama cautions us not to confuse this highest, greater esoteric or innermost secret non-dual teaching

with the lesser esoteric Mahamudra and Madhyamaka of sutra and lower tantra. This difference in subtlety is the essential difference between the “highest” teachings and the teachings of the “lower” tantras and sutras. Dodrupchen’s “effulgent rigpa” of the clear light is the aspect of rigpa that is

“experienced” when conceptual thoughts (vikalpa) of the less subtle mind states are present—“rigpa that arises from the ground, and is the appearance of the ground.” “Essential rigpa” is the indwelling, pure direct “experience” in the yogin/yogini—free of any conceptual elaboration— the experience of the

non-dual ultimate “fundamental innate mind of clear light.” Moreover, this tantric clearlight mind is essentially the same as the sutrayana non-dual “transcendent wisdom” of the Prajnaparamita Sutra, beyond or prior to subject and object, self and other, and all the dualities of the conditional

spacetime dimensions of the world of empirical relativeconventional truth. So there is effulgent rigpa of the appearances of the Ground or Base, and essential rigpa of the actual Ground or Base. But Dodrupchen also identifies rigpa that is both, and rigpa that is neither. In the former there is rigpa of

the conceptual appearances arising from the Base, effulgent rigpa, but here, in “rigpa attaining its full measure” the yogin/yogini has taken a “firm stance within the essence of the Base,” essential rigpa. Here then, we have both effulgent and essential qualities and experiences of rigpa. However,

Drodrupchen’s fourth alternative is rigpa that is neither effulgent nor essential rigpa. This is the “rigpa of all-embracing spontaneous presence (lhundrub), the dharmakaya wisdom of fruition” that is the “ultimate fruition. . . the ultimate state of freedom . . . exhaustion of phenomena beyond the

mind” (H.H. The Dalai Lama, 2000). . . Longchen Rabjam (1308-1364) the great synthesizer of the Dzogchen transmission teaches: Self-arising wisdom is rigpa that is empty, clear and free from all elaboration, like an immaculate sphere of crystal . . . it does not analyze objects . . . By simply identifying that

non-conceptual, pristine, naked rigpa, you realize there is nothing other than this nature. . . This is non-dual self-arising wisdom. . . Like a reflection in a mirror (melôn), when objects and percep

tions manifest to rigpa, that pristine and naked awareness which does not proliferate into thought is called the ‘inner power (tsal), the responsiveness that is the ground (gzhi) for all the arising of things’. . . For a yogin who realizes the naked meaning of Dzogpachenpo, rigpa is fresh, pure and naked,

and objects may manifest and appear within rigpa, but it does not lose itself externally to those objects. - Longchen Rabjam, The Treasury of the Dharmadhatu, (Commentary), Adzom Chögar edition, quoted in H.H. The Dalai Lama, Dzogchen, 2000 So the atavistic self-arising wisdom consciousness (rigpa) is primordially pure, and in Longchenpa’s words, “empty and clear”—the unity of emptiness and the clarity that is luminosity. Again, it is the prior “natural unity of one identity with two aspects.” Shunyata literally means empty (shunya) awareness

(ta). This Supreme Source or Primordial Base of the chaos of appearing energy forms is empty and aware—the unity of emptiness with its energy appearances arising upon the prana wind of awareness (lungta). Its essence is emptiness, primordial purity/kadag (trekchö practice): subjective “inner lucidity,” wisdom, dharmakaya ultimate truth. Its nature is awareness, spontaneous presence (lhundrub) of emptiness in every form (tögal practice): objective “outer

lucidity,” upaya/means, compassion, rupakaya, relative truth. The non-dual unity of these two truths is Dzogchen, perfect sphere of The Great Perfection of wisdom realized through the practice of Ati Yoga, utterly liberated and free of the twofold ignorance—forgetting and thinking—grasping at a self and grasping at phenomenal reality. This grasping and attachment results from the impure view that is the reifying conceptual elaboration (namtok) of relative-

conventional phenomena and states of experience of the ego-I of dualistic mind (sem) dwelling in the three times. The antidote, and beyond? “Without past, present, future; empty, awake mind.” As we have seen, this awake mind is the nondual unelaborated spontaneity of the fourth time (turiya, the fifth state of turiyatita) that abides within this relative-conventional moment, exactly as it is now. According to Tulku Urgyen, this luminous inner union of

emptiness and form is the deity Vajrayogini (Yeshe Tsogyal/Vajra Varahi). “Knowing one, liberates all.” Through knowing our Buddha Nature we are ever free. Through the path, conventional esoteric Sambhogakaya deity unites exoteric conceptually contrived Nirmanakaya form with Dharmakaya, beyond all duality, radically uncontrived ultimate truth, our singular Ultimate Basis or Sourceground. Lama Mipham on the Dzogchen view of these Two Truths of the Buddha, that

final truth of the always present unity of absolute emptiness and relative form: Within the essence, original wakefulness which is primordially pure, manifests the nature, a radiance which is spontaneously present. - Mipham Rinpoche What to Do? Choosing Our Reality. “It is only by training the mind that one reaches peace of mind” (H.H. The Dalai Lama). “The Meditation” of the path is the practice of training the mind in equanimity (upeksha/shanti), recognizing—“brief moments many times”—the “one taste” of this non-dual unity of Mind Essence, ever present state of pure presence that is the marvelous transcendent Primordial Awareness Wisdom, pointed out and mirrored (semtri/darshan/denbo) only by the Vajra Master.

Gradually through such “meditative stabilization” we learn: “Without changing anything, let it be as it is.” “Make of yourselves a light,” the Buddha’s last words to his disciples. Then let it shine. This is the difference in view and conduct between the dualistic deluded and negative materialism (“black diffusion”) of the massmind programmed individual consciousness of namshe that transmigrates through the bardo of the six realms and twelve links (nidana)

of the Bhava chakra—karmic wheel of the dependently arisen cycle of samsaric conditional existence—and our non-dual primordial wakefulness (rangjung yeshe). This beautiful original face is Yeshe, Vajrayogini, our unborn buddha nature that is the “single sphere of Dharmakaya.” Thus do we choose our destiny. Remaining naturally (in the state of rigpa) is the meditation. The nature of mind is Buddha from the beginning. . . Realizing the purity essence

of all things, to remain there without seeking is the meditation. - Garab Dorje (The Three Vajra Verses) Regarding the subject and object of meditation, this perfectly subjective transcendent wisdom consciousness—ineffable Supreme Source that is androgenous,

primordial Adi Buddha Samantabhadra—Longchenpa reveals that this fundamental ground in whom all appearing phenomena arise is without beginning and without end, unborn and uncreated, ontologically prior to the relative-conventional causality of appearing spacetime reality. What never existed, cannot cease to

exist. Therefore, arising objective phenomenal particulars and beings of the perfectly subjective Ground, who abide in an acausal spacetime transcendent relation of essential identity with this sourceground can have no creator for they are originally and primordially unseparate and ever embraced and

pervaded by this Ground. Phenomena, beings and the egoic sense of self are, in actuality, a perfectly subjective unity, beyond belief, prior to all apparent, interdependent spacetime arising. The painful perennial duality of creator/creation, of self and other—our uncomfortable “confront zones”—is

thereby transcended in its infinite non-dual Source, Ultimate Truth of Reality Itself (chö nyid). For Longchenpa Original purity in its essence has never existed as anything; rather its nature, like that of space, is primordially pure so that anything whatsoever can manifest. The origin of all samsara and nirvana is atemporal, with no beginning or end. . . The unique vast expanse . . . spontaneous presence…is not created by anyone. All things that emerge from it—all possible phenomena without exception—are one within the fundamental ground from which they emerge, since causality is negated . . . The

ultimate heart essence, which transcends existence and non-existence . . . is truly beyond all conventional expression and description. . . From the standpoint of enlightenment, the heart essence from which everything

arises, there is no duality . . . Buddhas, beings, and the universe of appearances and possibilities are evident, yet do not waver from the single nature of phenomena, just as it is. . . Leave everything as it is… Primordial buddhahood, the ground of fully evident enlightenment, unchanging, spontaneously

present, the basic space of the vajra heart essence—the nature of mind is natural great perfection. -Longchen Rabjam, The Precious Treasury of the Way of Abiding (Commentary), Padma Publishing edition, 1998 This same heart essence of innate clearlight mind, this “essential rigpa” that is the joyous blessing gift (jin lab) of the state of primordially pure

presence of the compassionate buddha nature within us was earlier transmitted directly to us through the Buddha’s Second Turning of the Wheel of the Dharma, revealed and elaborated, as we have seen, in the Prajnaparamita Sutra (The Great Sutra of Transcendent Wisdom), the heart essence of which is expressed in the Buddha’s sublime Heart Sutra. This transcendent unity of the Two Truths of Madhyamaka—the Perfection of Wisdom of sutra and tantra—and the

non-dual View of the unity of the Ground, Path and Fruit of Highest Yoga Tantra and of Dzogchen are expressed by the Buddha thusly: Form is no other than emptiness, emptiness is no other than form. . . The nature of mind is the unity of awareness and emptiness. . . The mind is devoid of mind, for the nature of mind is clear light. . . Leave everything as it is and rest your weary mind, all things are perfect exactly as they are…and all the Tathagatas will rejoice. -Shakyamuni Buddha (from the Prajnaparamita Corpus) Now, there is nothing left to do. So all that we do is selfless, authentic and kind. . . Who Is It? In whom does this all arise? -Adi Da Samraj

The primary Dzogchen tantra, The Kunjed Gyalpo (The Supreme Source), must be considered one of humankind’s great spiritual treasures. According to Chögyal Namkhai Norbu, this supreme non-dual teaching has been transmitted from master to disciple directly, heartmind to heartmind, for thousands of years. Its current tantric version dates from the 8th century C.E., and is a fundamental tantra of the Dzogchen semde teaching series. This version of the great non-

dual primordial teaching is derived from Buddhist sutra and tantra understanding of the Nature of Mind, yet its truth essence runs, like a golden thread, through the grand tapestry of humankind’s great Wisdom Tradition. Kunjed Gyalpo, The Wise and Glorious King is Samantabhadra/Samantabhadri in inseparable yabyum embrace—androgenous primordial Adi Buddha—state of pure presence, clarity and emptiness that is actually our original buddha nature, Supreme Source, Basis, primordial womb of everything. Samantabhadra, this Dharmakaya Buddha speaks to Vajrasattva, the Sambhogakaya Buddha: The essence of all the Buddhas exists prior to samsara and nirvana . . . it transcends the four conceptual limits and is intrinsically pure; this original

condition is the uncreated nature of existence that always existed, the ultimate nature of all phenomena. . . It is utterly free of the defects of dualistic thought which is only capable of referring to an object other than itself… It is the base of primordial purity. . . Similar to space it pervades

all beings. . . The inseparability of the two truths, absolute and relative is called the ‘primordial Buddha’. . . If at the moment the energy of the base manifests, one does not consider it something other than oneself . . . it selfliberates. . . Understanding the essence . . . one finds oneself always in

this state. . . dwelling in the fourth time, beyond past, present and future…the infinite space of self-perfection. . .pure dharmakaya, the essence of the vajra of clear light. - Chögyal Namkhai Norbu, The Supreme Source, (1999)

Thus do the sutras and the tantras of Buddha’s teaching, the dualities of the path— objective and subjective, self and other, observer and data, true and false, relative and ultimate—abide in the prior unity of the dependently arisen perfect sphere of infinite Mind Nature, ultimate truth, luminous innate

clearlight mind that is always the unity of awareness and emptiness. Who is it, that I am? All the masters of the three times have told it. This infinite vast expanse (longchen) of the Primordial Awareness Wisdom continuum is who we actually are. Tat tvam ami. That, I Am! Tat Tvam Asi. That Thou Art. That

(Tat) is our Supreme Identity, Great Perfection of our always present Buddha Nature, deep heartseed presence of ultimate happiness that is both origin and aim of all our seeking.

Begley, Sharon, Train Your Mind, Change Your Brain, Ballantine Books, 2007 Block, Ned (ed.), The Nature of Consciousness: Philosophical Debates, MIT, 1997 Boaz, David Paul, “Being the Whole: Toward the Emerging Noetic Revolution,” (2013) www.davidpaulboaz.org , The Noetic Revolution: Toward an

Integral Science of Matter, Mind and Spirit (2012), www.davidpaulboaz.org , Stromata, Fragments of the Whole: Selected Essays, “The Buddhist View,” (2009), “The Structures of Consciousness” (2008), www.davidpaulboaz.org Cabezon, Jose, with the Dalai Lama, Meditation on the Nature of Mind, translation and commentary of Khöntön Peljor Lhündrub, The Wish-Fulfilling Jewel of the Oral Tradition, Wisdom, 2011 Chalmers, David, The Conscious Mind,

Oxford, 1996 , “Facing Up to the Problem of Consciousness,” Journal of Consciousness Studies, 2:200-19, 1995 , “Does Conceivability Entail Possibility,” in Gendler and Hawthorne, eds., Conceivability and Possibility, Oxford, 2002 Clark and Chalmers, “The Extended Mind,” Analysis 58: 10–23, 1998, reprinted in The Philosopher’s Annual, Vol. 21, Ridgeview Press, 1999 Cushing, J. and McMullin, E. (eds.), Philosophical Consequences of Quantum Theory, 1989 Descartes, Rene, Principles of Philosophy, trans. Haldane and Ross, Cambridge University Press, 1644, 1911 Deutch, Eliot, Advaita Vedanta: A

Philosophical Reconstruction, East-West Center Press, 1969 Dōgen Zenji, Shobogenzo (edited selections), Thomas Cleary, University of Hawaii Press, 1986 Dowman, Keith, Maya Yoga (Longchenpa’s Gyuma Ngalso, translation and commentary), 2010 (manuscript, personal communication) Garfield, Jay (translation and commentary), The Fundamental Wisdom of the Middle Way (Nagarjuna’s Mulamadhyamakakarika), Oxford Press, 1995 Goldman, Steven, L., Science in the Twentieth Century, The Teaching Company, 2004 H. H. the Dalai Lama, The Universe in a Single Atom, Morgan Road, 2005

The Essence of the Heart Sutra, Wisdom, 2005

The Middle Way, Wisdom Publications, 2009 Jackson, Frank, “Epiphenomenal Qualia,” The Philosophical Quarterly, 1982 Klein, Anne C. (Rigzin Drolma) and Tenzin Wangyal Rinpoche, Unbounded Wholeness: Dzogchen, Bön, and the Logic of the Nonconceptual, Oxford University Press, 2006 Longchen Rabjam, Mind in Comfort and Ease (Samten ngalso), Commentary by H. H. The Dalai Lama, translated by M. Ricard and R. Barron, Wisdom, 2007 McGinn, Colin, “Can We Solve the Mind–body Problem,” Mind, 1989 Nagel, Thomas, “Panpsychism,” in Nagel, Mortal Questions, Cambridge, 1979 Newberg, Andrew, Principles of Neurotheology,

Ashgate, 2011 Newland, Guy, Introduction to Emptiness, (Tsongkhapa's Lamrim Chenmo, discussion), Snow Lion, 2009 Norbu, Chögyal Namkhai, Dzogchen: The Self-Perfected State, Snow Lion, 1996 Padmasambhava, Natural Liberation, trans. B. Alan Wallace, Wisdom, 1998 Penrose, Roger, Shadows of the Mind: A Search for the Missing Science of Consciousness, Oxford, 1994 Pettit, John W., Mipham’s Beacon of Certainty, Wisdom, 1999 Quine, W. V., Ontological Relativity and