The Drama of Cosmic Enlightenment

Lecture 96: The Drama of Cosmic Enlightenment

We are all human beings. And as human beings our main concern, our main function if you like, is to grow as human beings, to develop, to evolve. And that means sooner or later in one form or another following what is usually called a spiritual path or, in the terminology that we have been using more recently, pursuing the path of the Higher Evolution of Man.

In the course of the last few years, in discussing this process, this process of growth, development, Higher Evolution, we've operated, as it were, with the help of three main concepts.

First of all there's the concept of a state of unconsciousness or unawareness; secondly a state of self-consciousness or awareness, or if you like of individuality, or true individuality; and thirdly and lastly there's the concept of what we may describe, very provisionally and inadequately, as the state of universal consciousness, or Buddhahood.

And the Higher Evolution itself consists, as we have seen, on a number of occasions and from various points of view, consists in the whole overall process of development from the state of unconsciousness through self consciousness to universal consciousness or if you like from unawareness through awareness, through individuality, up to Buddhahood itself.

And as I mentioned last week, we shall soon have to start operating with the help of a fourth concept, a concept which we haven't so far introduced into our consideration of the Higher Evolution.

And that is the concept of what Jung calls - again a provisional term - The Collective Unconscious. And when we speak of the collective unconscious we include what Jung also calls the archetypes of the collective unconscious - the shadow, the anima or animus, the wise old man, the young hero, and so on.

And sometime we shall have to try to understand what part they also play in the process of the Higher Evolution. But this is something we shall have to do later on, maybe next winter.

Meanwhile, we're going to start moving in that direction. We're going to start familiarizing ourselves with, as it were, archetypal material in general. And we're going to study therefore in our present series of lectures the parables, the myths, and the symbols of the White Lotus Sutra. Now the White Lotus Sutra is a Mahayana sutra, that is to say a Mahayana scripture.

So last week, in the course of the first lecture in the series, we had something to say about the Mahayana, especially about the universal perspective of the Mahayana. And we saw that the word Mahayana itself, which is a Sanskrit word, means simply the 'Great Way', and that it constitutes, in historical terms, the second of the three great stages of the development of Buddhism in India.

We were especially concerned to point out last week that whereas all forms of Buddhism are in principle universal, Buddhism itself being a universal teaching, the Mahayana, the Great Way, is more effectively universal, more universal in practice, than the Hinayana, or the Little Way.

We saw last week that this was because the Mahayana stressed in its teaching, in its practice, in its spiritual life, both Wisdom and Compassion. And we saw that in so doing it followed faithfully the example of the Buddha himself.

We saw that after his Enlightenment, after his own awakening to the Truth, to the ultimate Reality of things, the Buddha did not remain, as it were, silent, he did not sit still, he did not wait for people to come to him.

The Buddha went out to them; he went forth to communicate the truth that he had discovered to other human beings, went forth out of compassion.

So the Mahayana is just like this; it follows the example of the Buddha. It does not wait for people to come to it. It goes out to them. And it goes out in many different ways, in many different forms.

We saw that even in ordinary linguistic terms the Mahayana goes out to people. The Mahayana doesn't expect people of different countries to learn its language in the literal sense, the language of its scriptures.

It speaks their languages, it translates its scriptures into their languages, into Tibetan, into Chinese, into Mongolian, into Japanese, and so on. And not only does it speak many different languages literally, but it speaks many different languages metaphorically too.

There are two great languages that humanity uses, that the Buddha himself used, and we find the Mahayana using, communicating in, both of them. It communicates in the language of concepts, through its intellectual teaching, its philosophy; and it also communicates in terms of images.

In the first language, the language of concepts, it addresses, we may say, the head. And in the second language, with the help of the second language, the language of images, it addresses the heart, even the unconscious. So we see that the Mahayana, like the Buddha himself, employs on occasion these two great languages, these two great means of communication - the concept and the image, or the idea and the image.

And in this way it

reaches, it is able to communicate with, a very large number of beings.

Now this week we are concerned with the White Lotus Sutra itself.

As we saw last week, this is one of the most important of all the Mahayana sutras.

There are many hundreds of Mahayana sutras. About a dozen or fifteen of them are of the greatest importance, and the White Lotus is perhaps one of the two or three most important of all.

And when we turn to the White Lotus, we find that it differs very considerably from most even of the other Mahayana sutras. We find some Mahayana sutras speaking the language of concepts almost exclusively.

We find others speaking the language of concepts and the language of images. But when we turn to the White Lotus Sutra, we find that it speaks, as it were, the language of images almost exclusively.

It contains parables, myths, symbols, but very very little in the way of conceptual exposition of the Dharma, very very little of what can be recognised as teaching in the ordinary sense of the term.

Now tonight we're concerned with the White Lotus Sutra as a whole. And, as the title of tonight's lecture tells us, we're concerned with it in a particular way, in a particular form.

We're concerned with it not just as a text or a document, much less still a teaching - we're concerned with it as nothing less than the Drama of Cosmic Enlightenment. From next week we shall be dealing with the significance of individual parables, myths, and symbols contained in the sutra.

But tonight we are still at the introductory stage. Tonight we're still trying to see the wood as a whole, rather than stopping to look at individual trees.

Now in the original Sanskrit the title of the White Lotus Sutra is Saddharma Pundarika Sutra. 'Saddharma' is usually translated as 'Good Law', or 'Good Doctrine', and it refers to the Buddha's teaching. But this translation isn't really very adequate.

'Sat' or 'sad' is derived from a Sanskrit root meaning 'to exist', and it therefore means something more like 'true' or 'real', or 'genuine' or 'authentic'.

And in the same way 'dharma' is not just 'doctrine' or 'teaching', as we usually translate the word; it's more like 'truth', it's more like, even, 'the ultimate nature of things'. So 'Saddharma', as well as the Pali equivalent 'Saddhamma', is best translated as 'the real truth' - this is what the term essentially means.

And some of you may remember that in my translation of the Dhammapada where the word often occurs in its Pali form Saddhamma, there also I've rendered it as 'the real truth'.

Now what does 'Pundarika' mean? 'Pundarika' means 'the white lotus'. In English we've got just one word for lotuses in general, but in the Sanskrit they've got a separate term, a separate word, for different lotuses of different colour.

So 'Pundarika' is the white lotus. And obviously here the white lotus is a symbol of purity. I'll have something to say about the symbol of the lotus in general when we come to lecture seven, entitled 'The Jewel in the Lotus'.

But meanwhile just one or two words. We know, I'm sure, that the lotus generally grows in ponds, generally grows, in fact, in the mud, or out of the mud. But according to Indian tradition and symbolism, though it grows in the mud and out of the mud, the lotus, the lotus flower, is never touched by the mud, it is never stained.

So in this way it becomes a symbol of purity, it becomes a symbol of the presence of the Unconditioned in the midst of the conditioned, or if you like a symbol of the spiritual in the midst of the worldly, the Transcendental or the Unconditioned or the spiritual not being touched, not being smirched, by that in the midst of which it appears.

So by describing the real truth, the Buddha's teaching that is to say, as being like a white lotus, it is suggested that that teaching, that real truth, though it appears in the world, is not affected, not tainted, by any worldly considerations.

And what about the word 'sutra'? This is the most common term for a Buddhist scripture. When we say 'the Sutras', we mean 'the scriptures', just like a Christian might say 'the Bible'.

The word 'sutra' itself is from a word meaning 'a thread', and it suggests a number of topics as it were strung together on a common thread of discourse. Now the body of a sutra, the body of a scripture in this sense of the term, usually consists of an exposition of the Dharma, of the teaching, of the real truth, by the Buddha himself.

And it's almost always preceded by an account of the circumstances in which, or under which, the discourse was delivered, and it concludes with an account of the effect produced on the auditors by the delivery of the discourse.

Sometimes, however, the Buddha himself remains in the background. He's there, but he doesn't actually speak. A disciple speaks, and at the end of the discourse the Buddha gives his approval, thereby making the discourse, as it were, his own.

And sometimes, especially in Mahayana sutras, a disciple speaks and he speaks under, as it were, the direct inspiration of the Buddha, so that it's the Buddha speaking through the disciple, and not the disciple himself speaking at all.

But whether the Buddha himself is speaking in his own person, whether he approves the words of a disciple, or whether he inspires a disciple, whatever is said in any of these ways in the body of a sutra is understood as issuing not from the ordinary level of consciousness.

It isn't just something worked out intellectually, it isn't something merely empirical in the mundane sense.

Ultimately it is a truth, a message, a revelation if you like, issuing from the depths of the Buddha's or the disciple's - at this level it doesn't make any difference - Enlightened consciousness, so that it's as it were a revelation, a communication, at least an expression, of the content of that Enlightened Consciousness, or the Buddha Nature - this is the essential content of a Buddhist scripture, its essential purpose, to communicate the nature of Enlightenment, and indicate the way leading to the realization thereof.

So if we take our whole title of this sutra in the original Sanskrit 'Saddharma Pundarika Sutra', we can render it as 'The Scripture of the White Lotus - or if you like the Transcendental lotus - of the real truth'.

This is only approximate, but it'll do . Now as a literary document, and I stress that it's as a literary document, the White Lotus Sutra belongs to the first century of the Christian Era - that is to say, it belongs to a period roughly five hundred years after the passing away of the Buddha himself.

If we look at the course of Buddhist history, if we look at what was happening in the Buddhist world in India at that time, we find that there was at that time a great writing down of Buddhist scriptures, in all sects, in all schools.

It isn't generally realized that until then, for practically the whole of that five hundred year period after the Buddha's death, the teaching, the doctrine if you like, the message, was transmitted entirely by oral means.

We know that the Buddha himself did not write anything, not a single word, not a single line. There's no actual evidence that the Buddha himself could even read and write. In those days reading and writing wasn't a very respectable sort of accomplishment.

It was the sort of thing that only those corrupt businessmen did who wanted to keep a record of their international business transactions and so on. But religious people didn't usually learn to read and write. Everything was transmitted orally.

So the Buddha taught orally. People gathered around him, listened to his words, then they repeated them to their disciples, they repeated them to their disciples, and in this way, in the case of Buddhism, and in the case of Hinduism too, over an even longer period, the message, the teaching, was transmitted from one generation to another, just like runners in a race handing a lighted torch to relay after relay.

But by the time we come to the first century of the Christian era, we find that for one reason and another the Buddhists in India started writing down their teachings, writing them down in Sanskrit, writing them down in Pali, writing them down in Prakrit, and Apabramsa, Pisachi, and so on. We don't really know why this occurred.

Some scholars suggest that memories had grown a bit weaker, not quite so good as they were in the Buddha's day.

Also, people didn't feel quite so sure, so confident.

They felt maybe there was a danger of the teaching being lost, so better write it down.

It also may be that reading and writing became generally more respectable, more cultural, and so it was a natural thing to start having the teaching in a written, recorded form. But anyway, there was this general writing down of the scriptures in the first century of the Christian Era, and amongst other scriptures this White Lotus Sutra was also written down.

Now we don't even know where it was written down. People generally assume that well, as it was an Indian Buddhist scripture it must have been written down in India, but this is not necessarily so, because by this time Buddhism had spread into central Asia, especially Mahayana Buddhism, and the White Lotus Sutra may have been written down there for the first time.

After all it was in Ceylon, not even in India at all, that the Pali scriptures were first written down, at about the same time, the same period. And the White Lotus Sutra was written down in Sanskrit, which was of course the language of ancient India.

In fact, to be perfectly accurate, the White Lotus Sutra was written down in two kinds of Sanskrit.

It was written down in what is called 'Pure Sanskrit', by which we mean Parninian Sanskrit, the form of Sanskrit which follows the rules of the great grammarian Parnini. And it was also written in down in what Egerton calls 'Buddhist Hybrid Sanskrit', which is not so pure Sanskrit, or Sanskrit written with a mixture of Prakritisms.

Now the structure of the White Lotus Sutra from a literary point of view is rather curious, not to say odd.

First of all you get a passage, say of a few pages, in prose. Then after the prose passage there comes a passage in verse. And the passage in verse repeats in verse what had already been said in prose, with very few variations, though there are some variations, including some expansions and some contractions.

Now the point is that the prose passages, the alternate prose passages, throughout the text are all in pure Sanskrit, Parninian Sanskrit; whereas the verse passages, the alternate verse passages throughout the text, alternating with the prose passages,

these are all in Buddhist Hybrid Sanskrit.

Now some scholars maintain that the verse portion is older than the prose portion, but there's no real proof of that, and this isn't accepted by all scholars. And the whole work is divided into 27 chapters - it's a quite substantial volume, the whole sutra - 27 chapters, in some recensions of the text into 28.

Now in the case of many Buddhist scriptures, especially Mahayana scriptures, we don't possess the original Sanskrit or Prakrit text. But in the case of the White Lotus Sutra, we are, well, fortunate.

The original text in these two kinds of Sanskrit does survive. Copies were discovered in the last century, and in this century also, in Nepal - many copies discovered there - in central Asia, in the sands of the desert, and also in Kashmir - the Kashmir texts were discovered only a few decades ago. There are ancient translations of the White Lotus Sutra into Chinese, into Tibetan, and into other languages.

And the standard Chinese translation of this text was the work of one of the greatest of all Buddhist translators and scholars, Kumarajiva, in the fifth century. This great translation was executed during the Tung dynasty, during which Buddhism was very predominant in China, and the translation itself is considered, by the Chinese, as a masterpiece of classical Chinese literature.

It was a very great achievement, a very great accomplishment indeed, and the work in Kumarajiva's translation exerted for hundreds of years a very great cultural influence, an influence perhaps comparable to that of the authorized version of the Bible in English.

And time and again in Chinese painting, for instance, we find great artists illustrating scenes from the White Lotus Sutra, depicting them as actually described in the text of the sutra. Unfortunately there's only one complete published English translation of this important sutra, and that is the translation made by the Dutch scholar Henrich Kern, and this translation was published by Max Muller in 1884 as Volume 21 of the Sacred Books of the East series.

As it was a first translation, and as in those days the meaning, the real meaning, of a number of important Buddhist technical, doctrinal, and spiritual terms wasn't known, it isn't surprising that the translation, though very good for its time, isn't really very adequate. It's rather unimaginative.

It's still in print, there are two prints of it current at the moment, but unfortunately the work contains, the translation contains, some very odd footnotes indeed by the translator.

The translator seems rather obsessed by the idea that the whole of Buddhism can be explained in terms of astronomy, and there were some very odd footnotes in which the translator tries to make out that Nirvana, the Buddhist state of Enlightenment, is equivalent quite literally to the state of physical extinction or death and just that, and there are many other footnotes in accordance with these sort of ideas.

There's another partial translation from Kumarajiva's Chinese translation.

That's the translation made by Soothill, who was a missionary in China; and his version, though it's a partial one, is much more readable, and has much more of the spirit of the original, and even though the translator was a Christian, and a missionary at that, he does succeed in conveying a very great deal of the devotional fervour and spiritual mood, as it were, of the original text. But his partial translation, unfortunately, is out of print.

But if you can get hold of it it certainly is worth going through.

Our celebrated Buddhist scholar and translator Dr Conze, who's translated practically all the Perfection of Wisdom texts, has also translated a few chapters, unfortunately very few chapters, of the White Lotus Sutra;

and I myself for the past many years have been trying to persuade him to complete his translation and give us the whole text, but so far he hasn't complied with these requests.

I suspect it's because in the depths of Russia somewhere there's a very important but obscure manuscript, another version of the sutra, which he hasn't had the opportunity of consulting; and until he's consulted it, he's probably not going to complete his translation.

So meanwhile we are left with Kern and Soothill, unless we can of course read the sutra in the original Sanskrit, or the Chinese translation, or the Tibetan translation.

Now the White Lotus Sutra begins with the words: 'evam me sutam' [[[Pali ]]- evan meya shrudam

(?) in Sanskrit], and it is worth noticing that all sutras whatsoever, all Buddhist scriptures whatsoever, begin with these words. As soon as you find these words occurring, you know that this is a Buddhist scripture.

And the words mean: 'Thus have I heard'.

So the question that at once springs to one's mind is:

'Who has heard? Who is the speaker who is saying:

'Thus have I heard'? Now according to tradition the speaker is Ananda.

Ananda was the cousin of the Buddha, he was his disciple, and for many many years, more than twenty years, he was his constant companion and attendant and fellow traveller. And again according to tradition Ananda, being always with the Buddha, especially in his later days, is the principal source of the oral tradition.

Ananda, we are told, was 'bahu sruta', he had heard much, and he had a very retentive memory. Whatever the Buddha said, whatever discourse he gave, Ananda was able to remember it almost word perfect and pass it on to his disciples.

He had a sort of agreement with the Buddha, a friendly understanding if you like, that if he happened to be away on any errand when the Buddha gave a teaching to anybody, then when he came back from his errand the Buddha would repeat it to him so that he had in his retentive memory a collection of all the discourses and sayings that the Buddha had ever uttered.

Now I must confess that when I first came into contact with Buddhism I did rather tend to wonder whether this was possible. But I must say that in the course of my twenty years in India I certainly did meet a number of people with very very retentive memories, not only Indians but Tibetans also who could reel off hundreds and hundreds of pages of scriptures by heart.

And not only that, but when I came back to this country, in the course of my work I got to know somebody who had a no less retentive memory, rather like a tape recorder, and rather to my surprise he'd sometimes say:

'On such-and-such date three years ago you said so-and-so', and he'd reel it off word perfect, just like that.

And apparently he remembered everything I'd ever said, on all sorts of religious and spiritual and cultural topics, it was all clearly in his mind, as I say word for word, the very order in which I had touched on certain topics, the exact nature of the argument, each stage successively, logically, and so on, all the illustrations together with dates, times, circumstances, everything.

So I thought to myself: 'Well, if this is possible even in London in the twentieth century, well, no doubt it was possible in ancient India too, and the Buddha did have in Ananda someone with this same phenomenal capacity to remember discourses and conversations and so on.

So anyway, according to tradition Ananda is the source of the teaching, it was he who remembered more than anybody else, and who after the Buddha's death taught to others what he had remembered of the Buddha's utterance.

But we can interpret these opening words: 'Thus have I heard', in a less literal, even in a more, we may say, esoteric manner. We know that the Buddha isn't outside us, ultimately, the Buddha nature isn't outside us, it's inside us.

And in the same way there's not just an Ananda outside, there's an Ananda inside. And it's also the Ananda inside who hears.

So in this way Ananda is the embodiment as it were of our own ordinary mind listening to the utterance, harkening to the utterance, of our own Enlightened Consciousness within. It's as though within us there are two minds, two consciousnesses.

There's the lower one, and the higher one. Usually the lower one ignores the higher one, it goes its own way, maybe doesn't even know that there is a higher one. But if it just stops, if it just listens, if it just, as it were, looks up then it can see, as it were, within its own mind this higher consciousness, its own higher consciousness, its own Enlightened mind - and can not only see, but can hear, can listen to, can be receptive to.

So Ananda stands for this lower mind, as it were, our ordinary mind, being receptive to the utterance, the deliverance, of the higher mind within ourselves, the Enlightened mind.

So pursuing this line of thought we can say that the whole Drama of Cosmic Enlightenment with which we are concerned this evening takes place not only without, not only on the stage of the cosmos but also within the recesses of our own heart.

Now I'm going to give a brief résumé of the sutra, and I'm afraid we shall find ourselves in a very unfamiliar world, a very strange world indeed.

I think I've mentioned before that once when I was in Bombay a friend of mine gave me to read a book which he thought I might find interesting, and it was a work, I must say a very good work, of science fiction. And he handed it to me with the words: 'You'll like this very much, I think. It's just like a Mahayana sutra.'

And it was. So it's in the same sort of world in a way, but perhaps more spiritual, more Transcendental, that we're going to find ourselves this evening. And we certainly won't be able to understand it at all well, if at all, and I'm afraid I'm not going to offer anybody very much help.

I'm going to relate as briefly as I can some of the events described in the sutra and I'm going to leave them just to make their own effect, however strange, however bizarre, however unfamiliar, however unintelligible, however incomprehensible. I'll offer a few comments only when absolutely necessary.

I'm going to ask everybody just to listen, and if you can, or if it occurs spontaneously, just to visualize the scenes described. And there's one thing that you mustn't do: you mustn't think. You mustn't try to work it all out, you mustn't ask yourself what it all means, or what the Buddha's getting at or what the Sutra's getting at. Just let the mind, in that sense of the term, stop working, stop ticking as it were.

If you want to work it out intellectually, if you can, you'll be able to do that perhaps, or at least try to do that, later on.

But for the moment, or for the rest of the hour rather, just sit back, just listen, and if you can, just visualize, and, as it were, look at the content of the Sutra just as though you were watching a film in the darkness, and as though your rational mind, your rational consciousness had gone to sleep, and you were seeing on the screen something, as it were, Transcendentally surrealistic, and you realize you haven't a hope of working it all out, so just look at the pretty pictures, and let them make their own effect. And, of course, don't be afraid of allowing oneself to feel.

Now the scene or the Sutra opens at Rajagriha. It opens on the Vulture's Peak. And in terms of mundane geography, the Vulture's Peak is an enormous rocky crag overlooking, if you like overhanging, the great city of Rajagriha.

I've been there, I've climbed up there several times, and that peak does command a really magnificent view, a view for many many miles around. In the Buddha's own day Rajagriha, which means 'royal house', was the capital of the kingdom of Magadha, which was the kingdom of Kosala, which in the Buddha's day was one of the two great kingdoms of Northern India.

And the Buddha often used to stay up on the Vulture's Peak when he wanted, as it were, to get away from it all.

And from the Vulture's Peak he could see far below in the distance the roofs, the tens of thousands of roofs, of that great city.

Well, there are no roofs there now - there's no city there any more. If you stand on the Vulture's Peak now and look down all that you will see is dense jungle, which is inhabited by leopards, and here and there a few ancient Buddhist and Jaina and even prehistoric, Cyclopean, ruins.

Symbolically speaking, the Vulture's Peak represents the summit of earthly existence. It's a peak, it's the summit, it's the pinnacle. Go beyond and you're in the world of the Transcendental, the purely spiritual.

Now the Sutra describes the Buddha as seated on the Vulture's Peak - as it were halfway between heaven and earth.

Below there's only earth; above there's only heaven. And he's surrounded by tens of thousands of disciples of various kinds - he's surrounded, we're told, by twelve thousand Arahants, by those who've reached Nirvana in the purely negative, Hinayana sense of destruction of passions, without positive knowledge and illumination.

And then there are eighty thousand Bodhisattvas, and in addition there are tens of thousands of gods and other non-human beings, as well as their retinues, as well as their followers.

And we are told the Buddha delivers a great discourse. He delivers a discourse on infinity, a very popular Buddhist topic. He speaks on infinity, and he speaks for a very long time very eloquently, and everybody is deeply moved, deeply affected, deeply impressed, so much so that we are told flowers start falling from the sky. Beautiful flowers of many colours start raining down from the heavens, and the whole universe shakes and trembles in six different ways. And then, having delivered that discourse on infinity, the Buddha enters into deep meditation.

His eyes are closed and his whole body is perfectly still, perfectly rigid. And while he is meditating, as he is meditating, there comes forth from a spot between his eyebrows a brilliant ray of pure white light.

And the brilliance of this ray of light is so intense, the ray of light is so powerful, that it illumines in all the directions of space, innumerable world systems. It's as though a great searchlight had been turned on and swept all around the universe, so that one could see millions, and tens of millions, and hundreds of millions of miles into the depths of space. And then what does one see there?

One sees in the depths of space, world systems innumerable, universes innumerable, and in each and every one of them one sees much the same sort of thing that one sees in this universe, on this earth, or at least that one saw then, in those days, one sees in each universe, in each world system, a Buddha preaching, surrounded by disciples. One sees Bodhisattvas practising the six great disciplines.

So this is the spectacle revealed by this ray of pure white light, which issues from that spot between the Buddha's eyebrows as he sits there meditating. So naturally the great assembly is really astonished.

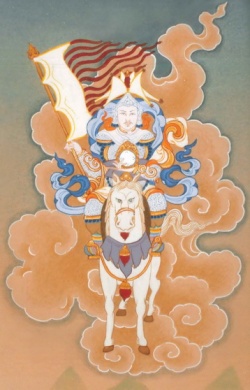

They wonder what it means, what it signifies, what's going to happen. And nobody knows. So Maitreya, one of the Bodhisattvas, the future Buddha, as he's sometimes called, asks the meaning of this phenomenon, and he asks Manjusri, the wisest of the Bodhisattvas, traditionally regarded as the incarnation of Wisdom - Manjusri is the Bodhisattva who's represented with a flaming sword, the sword of Knowledge, which cuts asunder the bonds of karma or conditionality. So Maitreya asks, 'What does it all mean? What is the significance of this great occurrence?'

So Manjusri says. 'I believe - I'm not sure - but I believe it means that the Buddha is about to proclaim the White Lotus Sutra.' So after he has said this the Buddha very slowly emerges from his meditation, and he opens his eyes and what does he say? He's as though speaking to himself, and he says, 'The Truth in its fullness is very difficult to understand.'

This is what he says, as it were spontaneously, as he comes out of his meditation - 'The Truth in its fullness is very difficult to understand' - so difficult, he says, that only the Buddhas, only the fully Enlightened ones, the perfectly Enlightened ones, are able to understand it.

Only they see, know, realize the Truth in its fullness, not others' - which is perhaps a very salutary sort of recollection for us, that it's only the Buddhas, only the fully Enlightened ones, who know the Truth in its fullness.

Everybody else, the Buddha tells the assembly, has to approach the Truth gradually, step by step, working their way into it, as it were, little by little.

And he goes on to explain that this is why he preaches the Arahant ideal, the ideal of gaining Nirvana, in the sense of extinction of passions only, first.

He doesn't preach all at once the higher, more Mahayanistic ideal of perfect Buddhahood, or realization of perfect Buddhahood by following the career of a Bodhisattva.

This he preaches only afterwards, when the lower truth, the lower ideal, has been assimilated, has been understood.

So he preaches step by step - he takes people, as it were by the hand, he says, and he leads them one stage at a time.

If he revealed the highest truth all at once people would be shocked, would be terrified, would be unable to receive, unable to assimilate.

We find something like this in the Tibetan Book of the Dead, where it is said that on death what happens first is that just in one blinding flash, as it were, Reality in its fullness dawns on the mind, but the mind is unable to receive it, it shrinks back terrified, and it falls to lower and ever lower levels of Reality, until it finds a level on which it is at home.

So the Buddha is in possession, as it were, of the full Truth, the highest Truth, but he doesn't dare, as it were, to reveal it all at once to his disciples.

He takes them step by step, stage by stage. He takes them so far first, then he shows them the next stage, and so on, until they get to the ultimate goal.

So he says on this occasion that he's not sure, looking round the assembly, he's not sure whether even now everybody is ready, everybody is prepared, to receive the highest Truth. He says, 'I've not yet given the highest Truth.

I've taken you all so far but there's still a bit farther to go, there's still a bit more to learn.

You don't know it all yet. There are many things that you don't know, which the Buddhas know, which I know, but which you do not yet know. You haven't really yet come to the ultimate goal.'

So this is what the disciples hear. And what happens? The Sutra says that at that point five thousand disciples walked out - a very dramatic little incident. They staged a walkout, and they murmured among themselves, and they said, 'Something more to learn? Good heavens, no! We know it all already.

What is the Buddha talking about? We're Enlightened, we've got Nirvana. Something more to learn? That's impossible! Maybe the Buddha's getting a bit senile. Something more to learn? - not for us!' - and out they all go, and they give, as they go out, the Buddha a very perfunctory bow, just for old times' sake as it were, and out they go, and they shake the dust of the assembly from their sandals or bare feet as the case might have been.

So here also is a lesson for us. It's only too easy to think that we know it all already, and sometimes we do intellectually, but that isn't really knowing it at all. If we're not very careful sometimes we think,

'Well, there's no further to go, I've got it, I've understood it, I'm there' - but this is the biggest danger of all. So they succumbed, those five hundred disciples, they succumbed to that danger, because they thought that they had nothing more to learn from the Buddha, that there was no Truth higher than that which they already had learned.

So the Buddha let them go. He didn't say anything, and when they had gone he simply said, 'Now the assembly is quite pure.' In other words, now the assembly consists of people who are receptive, who are prepared to consider that there may be something more for them to learn.

This rather reminds me of a little episode from English religious history, an occasion when a number of religious sectaries met with Oliver Cromwell, and they had a very terrific argument over some knotty points of scripture, and there was no moving them, they were really obstinate. And Cromwell, at the end, in desperation, said to them, 'Reverend sirs, I beg of you to consider the possibility that you may be mistaken.' So this is sometimes the point that is reached.

So, the assembly being pure, the Buddha tells them that his previous teaching of the three Yanas was only provisional, was only a temporary expedient made necessary by diversity of temperaments among the disciples.

And I must at once say that these three Yanas are not the three Yanas about which we heard last week. I'm afraid in Buddhism we get lots of terms with double meanings. In other words, these three Yanas are not the Hinayana, Mahayana, and Vajrayana.

They're a different set of three Yanas - I'm afraid I'll have to give you the Sanskrit terms first - the Sravakayana, the Pratyekabuddhayana, and the Bodhisattvayana - and these terms mean the way - Yana means way, or vehicle, or career - of the disciple, of the privately Enlightened one, as he's called, and of the Bodhisattva.

Now I don't want to go too much into technicalities. It's more important here to grasp the general principle.

The first two Yanas represent, we may say, different forms of spiritual individualism, the first perhaps being a bit more negative than the second.

The third Yana of course represents the Bodhisattva Ideal as contrasted with the other ideals.

But between them these three Yanas represent or symbolize different possible approaches to Enlightenment, so that when the Buddha says that his previous teaching about these three Yanas was only provisional, he is saying, and in fact he does say quite explicitly immediately afterwards, he is saying that in Reality there is only one way, Ekayana, one way, and this is the Great Way, Mahayana, the way leading to perfect Buddhahood. All roads go to Rome. All the other Yanas, he says, all the other ways, all

the other approaches, individualistic, altruistic and so on, they're all useful up to a point, but always ultimately merge, ultimately converge, into the way, all vehicles into the vehicle.

In other words, in our own terms, the Buddha is saying that there's only one process of Higher Evolution, and all participate in that process of Higher Evolution to the extent that they make an effort to develop.

A little later on the Buddha even tells the assembly that if anyone offers even a flower with faith and devotion then they are already, in principle, on the path to Buddhahood. One thing leads to another, as it were.

A small act of faith leads to a bigger act of faith; a small practise of the Way leads to a bigger practise of the Way, a more extensive practise of the way, and in this manner gradually, step by step, one gets into the Great Way, the One Way leading to Buddhahood, leading to perfect Enlightenment.

So that there is no good deed, the Buddha says, no religious act, no humanitarian act that falls outside the scope of the Way.

Now Sariputra, the oldest and wisest of the Buddha's disciples, hearing this teaching, this new teaching, is overjoyed. Though he's old, he's prepared to change, he's prepared to learn.

He says his only regret is that he's spent so much time in a lower stage, a lower level of understanding.

But the Buddha encourages him and the Buddha predicts that one day he will gain, he will realize, supreme Enlightenment as a perfect Buddha, at some date in the distant future, and he even tells him what his name then will be.

But not all the other disciples are like Sariputra.

Some become rather disturbed, rather perplexed, rather worried.

They don't know quite where they are. They say to themselves, 'Well, before we were given a certain teaching, we were following that; now something else is being given to us. Now we don't whether we should follow this, leaving the old practice.

We're not sure whether the old practice was completely useless. We're not sure whether we haven't wasted our time; we're not quite sure what we should do now, what we should do next.'

So to reassure them the Buddha tells the first of his great parables, and this is the parable of the burning house. And it's this parable that we shall be studying next week under the general title of 'Transcending the human predicament'.

Now four leading elders, when the Buddha has told this parable, are convinced.

They weren't so convinced by the Buddha's more abstract statement before, but they're convinced by this parable, which is perhaps significant in itself, and they realize that they can go a step further, that they can proceed beyond the purely negative state of eradication of negative emotions.

They can go on to positive illumination and supreme Knowledge, Wisdom, Enlightenment - in other words Perfect Buddhahood.

So they are very very pleased, they are overjoyed. And they give expression to their joy and they tell, or Mahakasyapa rather tells on their behalf, a parable of their own. And this is the parable, or if you like the myth, of the Return Journey.

And this parable, or this myth, will be the subject of lecture three.

The Buddha at this point praises the four elders, and he explains that he leads sentient beings to Enlightenment, to supreme Enlightenment, by adapting his teaching to their several different capacities. And to illustrate this point he relates two more parables.

These are the parable of the Raincloud, and the parable of the Sun.

We'll be dealing with these two parables in lecture four, entitled 'Symbols of Life and Growth'. And the Buddha then predicts Mahakasyapa and the others to perfect Buddhahood, and even their names are announced.

Now at this point interest shifts. It shifts from the future to the past. The Buddha turns to the whole assembly, and he starts telling them about a Buddha, another Buddha, who lived millions and millions of years before his own time.

And he tells them the story because this Buddha's career had in some respects parallelled his own.

The majority of the followers of this Buddha had followed the Hinayana path, had aimed at Arahantship, destruction of passions, and only sixteen of them, in fact his own sons from the period before he became a monk, had aspired to perfect Buddhahood as Bodhisattvas.

But he said all of them would one day enter the Great Way, the Mahayana, the One Way.

And to illustrate this point the Buddha tells the parable of the Magic City.

We're not going to have a lecture on this parable so I'll briefly recount it now.

The Buddha says that a guide is conducting a party of travellers through a dense forest. The road is very dangerous and very difficult, and the whole party is bound for a place called Ratnadvipa, which means 'the place of jewels'.

And on the way the travellers become exhausted, worn out, tired. They can't go a step further, they want to turn back. So they say to the guide, 'We're fatigued, we're exhausted, we can't go any further. Let's all go back.' So the guide thinks, 'Well, this would be a pity.

They've come so far.

Why turn back? What can I do?' So apparently he had some sort of conjuring or magic skill or power, so he conjures up a whole magic city. And he says to the travellers, 'Look, don't go back; there's a city here right in front of us.

Rest there, have something to eat, and then we'll see what is to be done.'

So the travellers are very pleased to see this magic city, and they spend the night there, they have something to eat, they have a good rest.

In the morning, of course, they feel much better, they're ready to carry on with their journey. So the guide just causes the magic city to disappear, and he leads them to the conclusion of their journey, they reach the Place of Jewels. Now in this parable, in this story, the guide is of course the Buddha, the Buddha in general, any Buddha.

The travellers are the disciples. The Place of Jewels is supreme Enlightenment, or perfect Buddhahood.

And what is the magic city? The magic city is the Hinayana Nirvana, that is to say the comparatively negative state of freedom from passions, without positive spiritual illumination.

Now the same sort of thing happens, we may say, with regard to the practice of meditation.

People come along and they want to start practising meditation, and they want to know what is the goal of meditation. So what does one say? One says that the goal of meditation is peace of mind.

This is what most people are after - they want just peace of mind. One doesn't say, when people want to come and practise meditation, one doesn't say straightaway, 'Well of course the goal of meditation is supreme Enlightenment, to become like a Buddha' - well, that's the last thing they want to become like.

They don't want to become like a Buddha, they're not interested in anything religious or spiritual, they just want peace of mind in the midst of their ordinary everyday life and work. And of course through meditation you can get peace of mind, certainly.

So they practise for a few weeks or a few months, maybe a year or two, and they get peace of mind, they experience peace of mind through the meditation.

And then when they've got so far they may one day ask, 'Well, is this all, or is there something further, something beyond?' And then it can be explained, 'Well, peace of mind is only an intermediate stage.

It's not the final goal of meditation, it's a sort of halfway house, not even halfway. Beyond peace of mind in the ordinary psychological sense there's a spiritual goal, there's Enlightenment, there's knowledge of the Truth, knowledge of Reality - what in Buddhist terms we call Perfect Buddhahood.

So having gained peace of mind, or at least having had some experience of peace of mind, one can now go on and try for Enlightenment, or at least for some deeper spiritual understanding, something above and beyond simple peace of mind in the mere psychological sense.

So this is what happens in the context of meditation.

And it's this, this is the sort of thing the Buddha is saying to his disciples happens, or at least happened in those days, in the context of the teaching as a whole.

The Buddha first of all speaks in terms of Nirvana, in the ordinary sort of psychological sense, and only when this teaching has been assimilated does he speak in terms of the higher spiritual goal of Supreme or Perfect Buddhahood.

So the Buddha having said so much, having told so many parables, the effect of all this begins to be felt by the audience, or by the assembly at large, and more and more of the disciples come forward, they confess their own shortcomings, their own limited understanding, and they announce their acceptance of this new teaching.

In this way Purna, the monk called Purna, and five other distinguished Arahants, are predicted to supreme Buddhahood, and they too give expression to their feelings by means of a parable, and this is the parable of the Drunken Man and the Priceless Jewel. And we'll be dealing with this parable in Lecture seven under the title of 'The Jewel in the Lotus'.

So as time goes on more and more disciples are predicted by the Buddha to perfect Buddhahood, and in fact all the Hinayana disciples are eventually converted. They all decide to aspire for supreme Enlightenment as Bodhisattvas.

So the Buddha at this point turns to all the Bodhisattvas present, that is, those who were Bodhisattvas from the beginning. And he impresses on them the importance of the White Lotus Sutra, and the necessity for its preservation.

And he explains that the whole text should be read, recited, copied, expounded, and even ceremonially worshipped. And all the Bodhisattvas promise to protect the Sutra.

Now at this point we come to the most dramatic scene in the whole of the White Lotus Sutra.

As they're all sitting there, something very strange happens.

From the earth, apparently from the depths of the earth, there springs up a Stupa, and it towers right up into the sky, a Stupa of stupendous size and unbelievable magnificence.

Now what is a Stupa, some of you may be wondering. We're going to learn in detail what a Stupa is in lecture six, on 'Five Element Symbolism and the Stupa', but for the present it will suffice to say that a Stupa is a sort of reliquary.

It's a monument containing, at least theoretically, relics, body relics, fragments of bone and so on, of the Buddha or his disciples. Originally, at the very beginning, following even a pre-Buddhistic practice, the Stupa was just a great heap or mound of earth, a sort of tumulus if you like.

Later on it came to be constructed of brick and stone. But this Stupa, the text says, the White Lotus Sutra says, this Stupa which appears springing out of the earth and towers up into the sky, which is so enormous and so magnificent, this Stupa is constructed not of brick, not of stone, not even of marble, but of the seven precious things, of gold, silver, crystal, lapis lazuli and so on.

And it's very very beautifully decorated with flags, and flowers and so on. And the whole Stupa emits light in all directions. It emits fragrance in all directions, and also music.

So one can just imagine the scene.

There are all these astonished disciples - only the Buddha isn't astonished - and this enormous Stupa towering from the earth into the sky, made of these seven precious things, beautifully decorated and sending forth light and fragrance and music in all directions of space.

And not only that, from the midst of the Stupa there comes forth a thunderous voice, and this voice praises the Buddha, that is to say Shakyamuni Buddha.

Shakyamuni Buddha is sometimes called 'our' Buddha, as he appeared in our world.

And this great voice, this thunderous voice, praises the Buddha, Shakyamuni Buddha, for preaching the White Lotus Sutra, and bears witness to the truth of everything that he has said.

Now all the disciples present are absolutely agog. They want to know what it all means, what is the significance, whose is the voice, whose is the Stupa, and so on.

So the Buddha explains that this Stupa contains the whole preserved body of a very very ancient Buddha called Abundant Treasures (that's the translation of his name in Sanskrit).

And the Buddha further explains that Abundant Treasures lived millions upon millions upon millions of years ago, and during his lifetime he made a vow.

And his vow was that after his death his Stupa, the monument in which his remains were enshrined, would spring forth wherever the White Lotus Sutra was being expounded. And not only that, but that he himself would bear testimony to the truth of the teaching.

So the whole assembly is very impressed by this explanation, and they ask if it isn't possible for the Stupa to be opened so that they can see the body of this ancient Buddha, Abundant Treasures, miraculously preserved after millions and millions of years.

But the Buddha says this isn't very easy, there are other conditions to be fulfilled. He says Abundant Treasures has another vow, and according to this vow his body in the Stupa, his preserved body, can only be seen under certain conditions, and these conditions have to be fulfilled by the Buddha himself, by Shakyamuni the Buddha. And the condition in this case is that he, Shakyamuni, must cause all the Buddhas who have ever emanated from him and who are preaching the Doctrine throughout the universe, to return to him and assemble together in one place - this is the great condition. So in compliance with that condition, Shakyamuni sends out a great ray of light, and this ray of light illumines the Buddha fields, the universes where Buddhas are preaching, in all the ten directions of space, so that the whole assembly once more can see the Buddhas in these far distant worlds. So when this light from Shakyamuni Buddha penetrates all these other thousands and ten of thousands of worlds and their Buddhas, the Buddhas there understand. It's a sort of signal - they know what is wanted, they know what is expected of them - so they tell their own Bodhisattvas that 'now I've got to go on a journey, thousands, millions of miles across the universe, to the other side of the universe as it were, a journey to the Saha world' - that's our world. In Buddhism, each world has got a name, each Buddha-world, each universe has got a name, and our world, our universe, is called the Saha world, which means 'the world of endurance', the world in which there's much to be endured. Because amongst all the worlds ours, we are told in the Buddhist scriptures, is not a particularly good one. It doesn't stand very high in the list of worlds, qualitatively speaking - there are lots of other worlds and universes with Buddhas and Bodhisattvas where conditions are very much better than they are in our own world. This is a world of suffering, of endurance, so it's called the Saha world. So the Buddhas in these other distant worlds tell their Bodhisattvas that they've got to go on this journey, this trip, to this distant little world, not a particularly nice one, in a distant corner of the universe, called the Saha world, because Buddha Shakyamuni has sent for them.

So Buddha Shakyamuni, as it were, doesn't like that these incoming Buddhas from all over the universe should see the imperfections of his own little universe, so he purifies the Saha world, the Sutra says, for the reception of all these Buddhas. And the whole earth is transformed into brilliant blue light, into, as it were, lapis lazuli. Everything, as it were, dissolves into a ground of brilliant blue light. And this ground of clear brilliant pure light is crisscrossed with golden cords stretching hundreds, thousands of miles in different directions, so that the whole brilliant blue ground is marked off into squares. And inside all these squares, we are told, there spring up

beautiful jewel trees, and these jewel trees, which are described at great length in many scriptures, are like trees but they're made entirely of jewels - their trunk, branches, leaves, flowers, fruits, are all made entirely of jewels, and they're hundreds and thousands of feet tall. And then, we're told, all the gods and men in the world, in this universe, other than those actually belonging to the assembly, are transferred elsewhere - we're not told precisely where, but they're sort of bundled out of the way. And all the villages in the world, all the towns, the cities, the mountains and the rivers and the forests - they all disappear. So you've got a perfect, a purified, a transfigured world left. This brilliant blue ground, crisscrossed with golden cords, and the jewel trees springing up in the squares. And the whole earth, we are told, smokes with sweet smelling incense, and the whole ground is covered and strewn with all sorts of heavenly flowers. And the preparations are barely complete when five hundred Buddhas instantly arrive from their own universes, in different directions of space, and each Buddha is attended by a great Bodhisattva, and they all take their seats on magnificent lion thrones underneath five hundred magnificent jewel trees. And such is the scale of things that with the arrival of these five hundred Buddhas all the available space is already taken up, and the Buddhas themselves have hardly begun to arrive. So what does Buddha Shakyamuni do? He hastily purifies, the Sutra says, untold millions of worlds in all the eight directions of space. And all of these, as soon as they're purified, are occupied by the streams of incoming Buddhas, who all take seats beneath innumerable jewel trees. And they all pay their respects to the Buddha Shakyamuni by offering a double handful of jewel flowers.

So when they're all gathered there, when all these Buddhas with their attendant Bodhisattvas - there must be millions of them - are all gathered together in one place, the conditions laid down by Abundant Treasures are fulfilled and the Buddha himself, Shakyamuni, rises, floats up into the sky, level with the great door of the Stupa, and he draws back the bolt, and he flings open the door, with a sound again like thunder, and that ancient Buddha, Abundant Treasures, is seen sitting crosslegged within. And even though his body is millions upon millions of years old it's perfectly preserved, perfectly intact, and he's seated crosslegged as though in meditation. And seeing this sight the assembly is of course struck with awe, and they scatter, they throw handfuls, heaps of jewel flowers over the two Buddhas. So Abundant Treasures isn't dead apparently - his body's perfectly preserved, he's still alive after millions upon millions of years, and he speaks. And he invites the Buddha Shakyamuni to come and share his throne, to sit down beside him. This is highly symbolical, highly meaningful, but we can't go into it now. You may perhaps have just a glimpse of the meaning. And this scene is very often depicted in Chinese Buddhist art, the two Buddhas seated side by side within the Stupa, sharing one and the same lion throne.

So there is the scene. There's this enormous Stupa towering up into the sky, and the two Buddhas now seated in the midst of it side by side, with all the congregation as it were, all these millions of Buddhas and Bodhisattvas on a lower level. But the whole congregation, the whole assembly, looking up into the sky, looking up at the Stupa, looking up at the two Buddhas, Abundant Treasures and Buddha Shakyamuni, desire to be raised up, lifted up, to the same level. So we are told that the Buddha puts forth his supernormal powers, and all the assembly, all the Buddhas, all the Bodhisattvas, millions upon millions of them, are lifted up into the air to the same level as Abundant Treasures and Shakyamuni himself.

And at the same time the Buddha cries out in a loud voice, saying, 'Who is able to preach the White Lotus Sutra in the Saha world?' Now, when he says that, or when he has said that, at this point in the Sutra, there occurs a whole group of episodes which may be a later interpolation, so I'm going to omit them. They rather break up the continuity of the action, and in any case our time is rather short. So continuing, in response to the Buddha's demand, 'Who is able to preach the White Lotus Sutra in the Saha world?', in response to this demand there come forward two Bodhisattvas, and they promise to preserve and propagate the White Lotus Sutra after the Buddha's death or Parinirvana. And all the Arahants who have been predicted to perfect Buddhahood, they give a similar pledge.

Now there are two women, two nuns standing to one side. These are Mahaprajapati, who was the Buddha's aunt and foster mother, and Yashodhara, who was his wife in the days before he left home. So they became nuns, or they had become nuns after the Buddha's Enlightenment, under his guidance, and they now are feeling rather sad, rather sorrowful, because they haven't been predicted to perfect Buddhahood. But the Buddha tells them that they too are sure one day of reaching perfect Buddhahood, and they too give a pledge to protect the White Lotus Sutra.

Now the Irreversible Bodhisattvas now announce their determination to disseminate the White Lotus Sutra throughout the whole universe, and the whole assembly, everybody present, Buddhas, Bodhisattvas, Irreversible Bodhisattvas, Arahants, monks, nuns, everybody, begs the Buddha to have no anxiety about the future of his teaching in the White Lotus Sutra. They say that dreadful days are coming, a very dark age is approaching, a time of war, a time of confusion, a time of bloodshed, a time of evil, but they tell the Buddha, 'Do not worry. Even in this dark age, this dreadful age that is coming, we shall remember the teaching. We shall preserve it, we shall protect it, and we shall propagate it'. And the Bodhisattva Manjusri comments that this is a tremendous responsibility, and the Buddha agrees. And the Buddha further says that in order to fulfill this mission of protecting and preserving and propagating the White Lotus Sutra, the Bodhisattvas who do this will have to be endowed with four qualities. He says first they must be perfect in conduct. Secondly, they must confine themselves to proper sphere of activity. They must avoid unsuitable company, and dwell inwardly in the true nature of Reality. Thirdly, they must maintain happy, peaceful states of mind, unaffected by zeal or envy. And fourthly and lastly they must cultivate feelings of love towards all living beings. These are the four qualities with which they must be endowed if they want to preserve and propagate the teaching of the White Lotus Sutra. And the Buddha explains each of these qualities in some detail, and ends up by telling a parable. It's the parable of the wheel-rolling king, or, as we would say, the universal monarch.

The Buddha says a certain king, a certain universal monarch, wished to extend his domains. So he went to war, and his soldiers fought heroically, so heroically, so well, so bravely that the king was very pleased with their behaviour, and he gave them all rewards according to their desserts. He gave houses, lands, clothes, slaves, conveyances, gold, silver, gems, he gave everything that he had in the palace to the soldiers because he was so pleased with their brave behaviour. But only one thing he kept back, only one thing he didn't give, and that was the magnificent crest jewel that he wore in his own turban on his own head. But eventually, the Buddha said, he was so pleased with their behaviour, they really had been so heroic, that at the end he took the crown jewel itself, the crest jewel itself, and he handed that also over to the soldiers. So in the same way the Buddha is pleased with the conduct of the disciples. He sees the effort that they have made. He sees how bravely they've fought with Mara. So he gives many more teachings, many more instructions, many more blessings as it were. And in the end, keeping nothing back, even the supreme teaching, he gives them, he teaches them, the White Lotus Sutra itself. This is the parable.

So at this point, having heard this parable, the great Bodhisattvas who've come from other world systems, other universes, with their own Buddhas, offer their services too. But Shakyamuni says no, your services are not necessary. He says, 'I have innumerable Bodhisattvas here in my own Saha world, and they will protect the White Lotus Sutra after my death.' So as he says this the universe shakes and trembles, and from the space underneath the earth there issues a great host, an incalculable host, of Irreversible Bodhisattvas, that is to say Bodhisattvas who've gone so far on the path that they cannot fall back into lower states, they're bound inevitably for perfect Buddhahood. So one by one all these Irreversible Bodhisattvas appearing from the space beneath the earth salute in turn all the Buddhas present. They then sing their praises. And these proceedings occupy fifty minor aeons. And during these proceedings the whole assembly remains silent, no one says anything. But through the power of the Buddha it all seems just like an afternoon, just like half a day.

And when all that's done, Buddha Shakyamuni and the four leaders of the great host of Irreversible Bodhisattvas exchange greetings, and everybody is amazed. The whole assembly, apart from the Irreversible Bodhisattvas, is amazed. And they wonder how the Buddha Shakyamuni can claim all these newly appeared Irreversible Bodhisattvas as his own disciples. But Shakyamuni reassures them, and he says, 'No, these are indeed my own disciples. They've all been following the Great Way for a very long time. You haven't seen them before, but they have been here. They live under the earth.'

But hearing these words the disciples become still more perplexed. They say, 'Look here. You gained Enlightenment under the Bodhi tree at Bodhgaya only forty years ago. How is it possible that you should have trained such an incalculable host of Bodhisattva disciples in a short time like that. A few hundred, a few thousand disciples even, but great hosts like that in forty years, how could you possibly train them? How could you possibly teach them? How could they possibly all be your disciples? And not only that, but they seem to belong to past ages, they seem

to belong to other world systems. How could they be your disciples?' They said, 'It's ridiculous. It's just like a young man of twenty five pointing to a whole crowd of hundred year old men and saying, 'Those hundred year old men are all my sons; and then the hundred year old men all say to the twenty five year old man "Father". It's as ridiculous as that.'

Now the Buddha has a reply. And the reply is what the Mahayana regards as a sort of central revelation, and this particular scene is therefore the climax of the whole drama of cosmic Enlightenment, and everything that's gone before leads up to this, to this moment. The Buddha says that he did not in fact gain Enlightenment forty years ago, or only forty years ago. He says that he gained Enlightenment an incalculable number of millions of ages ago. In other words, he makes the rather staggering claim that he is eternally Enlightened. Obviously it's no longer the historical Shakyamuni speaking. It's the principle, the universal, the cosmic principle of Enlightenment itself. And he says all this while, all these millions of ages, he's been teaching and preaching in many different forms, in many different worlds. That He appears as Dipankara Buddha, as Shakyamuni Buddha, and so on; that he's not really born, doesn't really attain Enlightenment, doesn't really die, only appears to do so, appears to do just so as to encourage people. He says if he remained with them all the time, never appearing or disappearing, but with them all the time, he said people will not appreciate him or follow his teaching. And he tells a parable to illustrate this, and this is the parable of the good physician. We'll be dealing with that parable in lecture number eight on 'the Archetype of the Divine Healer'.

So this great revelation of the Buddha, that he hadn't gained Enlightenment just forty years earlier, but that he was eternally Enlightened, universally Enlightened, this great revelation, this great declaration, produces a tremendous effect on the whole assembly. And hosts of disciples, hosts of those present, attain various spiritual insights, spiritual powers, understanding, blessings and so on, while showers of flowers and incense, jewels and so on fall down from the sky, and celestial canopies, the Sutra says, are raised on high. And countless Bodhisattvas then sing the praises of all the Buddhas.

The Buddha then explains that the development of faith - in the sense of emotional response to - faith in his eternal life, is equivalent to the development of Wisdom. Such faith, we may say, is Wisdom transposed into emotional terms. If one has this sort of faith, this sort of insight, then one will see the Buddha, realize the Buddha, experience the Buddha, or Buddhahood, or the universal principle of Enlightenment, will see the Buddha on the spiritual Vulture's Peak eternally preaching the White Lotus Sutra. Now the Buddha says that the merits of listening to the White Lotus Sutra are very great, and the merits of preaching it even greater. And of course it's very demeritorious to disparage the Sutra in any way.

And this warning introduces the episode of the Bodhisattva Never Direct. The Bodhisattva Never Direct, the Buddha says, lived millions of years ago, and used to go around telling the same thing to everybody. He'd say, 'It is not for me to direct you . You are free to do anything you like. But I would advise you to take up the Bodhisattva career, so that ultimately you may become perfect Buddhas.' So he used to go around saying this to everybody, and some of the people to whom he used to say this became very very angry. They didn't like to be told that they were going to be Buddhas one day, that was the last thing they wanted to become. And they became so angry that they not only abused the Bodhisattva, but they fell upon him with sticks and stones and gave him a very rough time indeed. But he didn't bear them any ill will. He retreated to a safe distance and he continued to cry out, 'It is not for me to give you any direction. You will all become Buddhas.' So he was nicknamed Bodhisattva Never Direct, and the Buddha went on to say that he himself in a previous life was Bodhisattva Never Direct. And some of his persecutors of those days were now disciples, monks, nuns, and Bodhisattvas.

Now the Irreversible Bodhisattvas from under the earth also promise to protect the White Lotus Sutra, and say that they will preach it throughout the whole universe. And this declaration, this promise of theirs, sparks off all manner of marvels and wonders. The Buddhafields in all the directions of the universe shake and tremble, and the inhabitants of all those Buddha worlds, all those universes in all directions of space, they look in to the Saha world, our world, and they all see it revealed, just like looking down through the depths of the water and seeing something at the bottom. And they all see the millions of Buddhas assembled on that occasion here in this Saha world. They see the Buddha Shakyamuni, they see the Buddha Abundant Treasures, seated on their joint lotus throne in the midst of the Stupa. And they see the countless millions of great Bodhisattvas. And Shakyamuni is joyfully hailed by all the gods, who throw flowers, incense and

jewels. And all these flowers, all the incense, all the jewels, they as it were come together in a solid mass, just like clouds massing together, and they transform themselves into a jewelled canopy. And this great jewelled canopy covers the whole sky above all those Buddhas. At this point further marvels take place, and eventually all the worlds in the universe, all the universes in the universe, reflect one another, just like mirrors, thousands, millions of mirrors all mutually reflecting one another. In this way all the universes throughout space reflect and mirror one another, so that all are seen in each one, and each one is seen in all. And all interpenetrate, like innumerable beams of coloured light intersecting, all interpenetrate without any obstruction or hindrance whatsoever. So that eventually a state is reached, a condition is reached, in which all these worlds, all these universes, with all their beings, their Buddhas, Bodhisattvas, human beings and so on, are fused into one harmonious Buddhafield, into one cosmos wherein the principle of Enlightenment reigns supreme.

So the Buddha then extols the merits of the Sutra, and finally reminds the assembly of the importance of preserving and propagating it, and the great drama then concludes. The Buddha rises from his lion throne in the midst of the sky, he places his right hand in blessing on the heads of the countless Irreversible Bodhisattvas, and he requests all the Buddhas present to return to their own domains, saying, 'Buddhas, peace be upon you. Let the Stupa of the Buddha Abundant Treasures be restored as before.' On hearing these words, everybody rejoices.

And such is the outline of the White Lotus of the Real Truth. Such in outline is the drama of cosmic Enlightenment.