The Inner Kālacakratantra - A Buddhist Tantric View of the Individual: The Transformative Body

The Inner Kālacakratantra

A Buddhist Tantric View of the Individual

A. Wallace

The Transformative Body

The Path of Actualizing Gnosis, the Individual, and the Path as the Individual

The Kālacakratantra's theory of the nature of gnosis, prāṇas, spiritual ignorance, and mental afflictions, as well as the relationship among them, provides the rationale for the Kālacakratantra practices for eliminating mental afflictions and actualizing the four bodies of the Buddha. Among the Kālacakratantra's multifaceted approach to the eradication of mental afflictions, several are especially significant. First, the path of eliminating mental afflictions is the path of sublimating the afflictive nature of mental afflictions into the peaceful and pure nature of the enlightened beings who are the pure aspects of the elements from which mental afflictions arise. Second, the path of sublimating mental afflictions in the Kālacakra tradition is the path of recognizing the ultimate nature of one's own mental afflictions, which is gnosis. This path is comprised of two methods. One is a conceptual method of familiarizing oneself with the ultimate nature of one's own mind by means of autosuggestion, specifically by means of generating oneself in the form of the deities of the kālacakra-maṇḍala. The other method is a nonconceptual method of spontaneous and direct recognition of gnosis as the ultimate nature of one's own mind. The first method, which is characteristic of the stage of generation (utpattikrama), is contrived and based on one's faith in the innately pure nature of one's own mind, and it uses primarily one's powers of imagination. Even though it is characterized by freedom from grasping onto one's own ordinary psycho-physical aggregates, or one's self-identity as an ordinary being, it is still characterized by holding onto the imagined self-identity. The second method, which is characteristic of the stage of completion (saṃpatti-krama), draws upon the experience of imperishable bliss and the direct perception of the innately pure nature of one's own mind, which is devoid of grasping onto any identity. Thus, on the path of sublimating mental afflictions, the Kālacakratantra adept starts the purificatory practices using one type of conceptualization in order to eliminate another type of conceptualization, and concludes with the eradication of all conceptualization. In this tantric tradition then, mental afflictions are nothing other than conceptualizations that obstruct the unmediated perception of the empty and blissful nature of one's own mind.

In the anuttara-yoga-tantras other than the Kālacakratantra, the primary goal of the path of sublimating mental afflictions is the purification of their immediate causes, beginning with the prāṇas. In those tantras, the purified prāṇas eventually become a purified material substance of the mind of clear light, and one's pure illusory body arises from this substance. In the Kālacakratantra, on the other hand, the primary goal of sublimating mental afflictions is the complete eradication of all present and future prāṇas. It is upon such complete eradication that the body of empty form, called “the form of emptiness” (śūnyatā-bimba), and the mind of immutable bliss arise. Since the cessation of the circulation of the prāṇas induces the actualization of Buddhahood in the form of Kālacakra, Buddhahood is characterized here as the “windless state” (avāta) that one attains by means of wind. Similarly, the nonabiding nirvāṇa (apratiṣṭhita-nirvāṇa) of the Buddha is also explained in terms of the absence of the wind of the prāṇas. 1 The eradication of the prāṇas is characterized by two conditions of the mind. First, due to the destruction of the prāṇas, one's dualistic mind becomes unified, and it becomes both the apprehending subject and the apprehended object. In this way, one's own mind becomes a form of emptiness (śūnyatā-bimba), in which conceptualizations cannot arise. Second, the destruction of the prāṇas and the elements that they carry eradicates the five psychophysical aggregates and, in their absence, imperishable bliss arises.

Thus, in the context of the Kālacakratantra, by completely extinguishing one's own psychophysiological constitution and processes, one extinguishes the source of one's own cycle of rebirth and attains the state of the eternal manifestation of the gnosis of supreme, immutable bliss. From the premise that one's ordinary psychophysical factors, which are composed of atomic particles, are the source of one's mental obscurations, arises the necessity of transforming the ordinary, physical nature of one's body and mind into their blissful nature. The Kālacakra tradition considers that process of transformation as the most direct means to the state of the mutual pervasiveness and unification of one's own body, speech, and the mind of immutable bliss.

The diverse aspects of this tantric path of actualizing the gnosis of immutable bliss are closely related to the previously described views of the Kālacakra tradition on the ways in which the four bodies of the Buddha are present within the individual and on the manners in which their powers manifest in the bodily, verbal, and mental capacities of the human being. In light of the Kālacakra tradition's identification of the individual with the four bodies of the Buddha, the path of actualizing the gnosis of immutable bliss can be seen as the path of bringing forth the true nature of one's own bodily, verbal, and mental capacities. The path of actualizing the four bodies of the Buddha is the path of the purification of the previously mentioned four bodily drops from the habitual propensities of spiritual ignorance, which are sustained by prāṇas. Therefore, in the Kālacakra tradition, the path of actualizing the fourfold mind of the Buddha is inseparable from the path of the sublimation, or transformation, of the prāṇas and nāḍīs in the body. In that regard, the phenomenal forms of the four bodies of the Buddha and the manners in which they manifest within every individual are most intimately related through their common causal relationship to the prāṇas. Their interrelation is even more clearly demonstrated in the Kālacakratantra's multifaceted, practical approach to the actualization of the four bodies of the Buddha. With regard to this, one may say that in this tantric system, the transformative body of the path of actualizing blissful gnosis is the path of the mind's self-discovery through the elimination of its inessential ingredients with which the mind falsely identifies itself. Thus, the transformative body of the Kālacakratantra path is nothing else than the gnostic body revealing itself in the process of elimination until there is nothing left to be identified with, until the basis for self-affirmation, or self-identification, ceases and nondual self-awareness arises.

As in other related tantric systems, here too, the transformative path of actualizing the gnosis of immutable bliss consists of the three main stages of practice: the initiation (abhiṣeka), the stage of generation, and the stage of completion. However, the contents of these three main stages of Kālacakratantra practice differ from those in the other anuttara-yoga-tantras, since the form of Buddhahood that is sought in this tantric tradition differs from those in the other related tantras. In this tantric tradition, the actualization of the four bodies of the Buddha as the four aspects of the Jñānakāya is instantaneous, but the path of purifying the four drops, which are the inner supports of the four types of the Jñānakāya, is gradual. The process of sublimating the four drops is characterized by the Kālacakratantra's unique path consisting of three types of accumulations: the accumulations of merit (puṇya), ethical discipline (śīla), and knowledge (jñāna). For this tantric system, the accumulation of merit results in the attainment of the first seven bodhisattva-bhūmis, and the accumulation of ethical discipline leads to the attainment of the eighth, ninth, and tenth bodhisattva-bhūmis. The accumulation of ethical discipline is defined here as meditation on reality (tattva), 2 and it is said to result from observing the tantric vows (vrata) and pledges (niyama), especially those related to the practices with a consort. Lastly, the accumulation of knowledge results in the attainment of the eleventh and twelfth bodhisattva-bhūmis, which are characterized by the actualization of the gnosis of imperishable bliss and by the unification of one's own mind and body. Consisting of not two but three types of accumulations, this tantric path is closely related to the yogic practices that are specific to the anuttara-yoga-tantras and to the relevant schema of the twelve bodhisattva-bhūmis.

Likewise, this entire tantric path of spiritual transformation is seen as being of two kinds, mundane and supramundane, due to the differing qualities of tantric disciples. Thus, the stage of initiation is said to be of two kinds: mundane (laukika) and unexcelled (anuttara). The mundane initiations are those that involve the generation of bliss by means of sexual union with an actual consort (karmamudrā). Due to their involvment with union with an actual consort, these mundane initiations are considered ineffective in bringing forth nondual gnosis, without which there is no Buddhahood; and their inefficacy is explained as follows. If in the union of the tantric couple, the bliss of the male consort that has arisen due to the female consort is the gnosis of the female consort, then the bliss of the female consort that has arisen due to the male consort is the gnosis of the male consort. In that case, there are two types of gnosis between the two consorts, which means that there is an absence of nonduality. Accordingly, the Vimalaprabhā asserts that the mundane initiations are taught not for the sake of bringing about the experience of nonduality but for converting people to this tantric path. 3 The unexcelled initiations, on the other hand, do not involve the union of two sexual organs but are practiced by means of the mahāmudrā-consort, or the empty form consort, and these initations do give rise to the nondual gnosis of imperishable bliss.

Similarly, the stage of generation, in which one meditates on the sexual union of oneself and an imagined consort (jñāna-mudrā) is regarded as a mundane sādhana, for it brings about only mundane results, such as the perishable experience of innate bliss and the mundane siddhis. The stage of completion, on the other hand, in which one meditates by means of the mahāmudrā-consort, is seen as the supramundane path to Buddhahood, for it induces the realization of the supramundane gnosis. Thus, the transformative body of the path takes on first a mundane form that is accessible to the tantric practitioner who is new to the Kālacakratantra theory and practice; and it gradually evolves into the supramundane form by means of which the mundane person is transformed into a supramundane being.

The Transformative Body of the Path of Initiation

This tantric path of the accumulation of merit, ethical discipline, and knowledge begins with the sevenfold initiation into the kālacakra-maṇḍala, and this is seen as the first step in enabling the individual's four vajras to eventually arise as the four bodies of the Buddha. It ends with two sets of the four higher initiations, intended for the advanced Buddhist practitioners. The first seven initiations authorize the initiate to engage in the meditations on mantras, mudrās, and maṇḍalas that will facilitate the elimination of mental afflictions and the consequent accumulation of merit. According to the Kālacakra tradition, they are given for the sake of converting sentient beings to this body of the path and for providing the initiate with an understanding of this tantric path. The four higher initiations authorize the initiate to engage in the meditation on emptiness that has the best of all aspects, which facilitates the accumulation of knowledge; 4 and the four highest initiations authorize the initiate to become a tantric master, a vajrācārya.

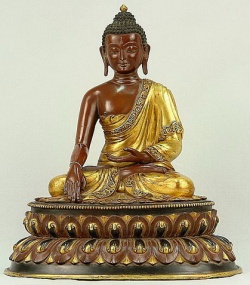

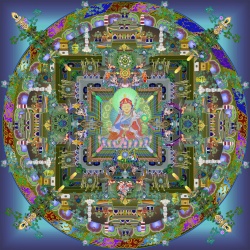

The initial method of manifesting the four bodies of the Buddha is characterized by the initiate's entrance into the kālacakra-maṇḍala through the four gateways of the maṇḍala-palace, which symbolize the four gates of liberation corresponding to the four bodies of the Buddha, and by the initiate's visualization of his own psycho-physical constituents in the form of deities. This visualization during the stages of initiation of one's entire psycho-physical makeup in the form of deities is unique to Kālacakratantra practice.

1. The first two initiations, the Water (udaka) and Crown (mukuṭa) initiations, are designed to induce the initial eradication of the obscurations of the drop in the lalāṭa cakra by sublimating the initiate's elements and psycho-physical aggregates, respectively. Thus, these two initiations, during which the initiate is led into the maṇḍala through the northern gate, are said to facilitate the transformation of the initiate's body and the eventual actualization of the five Tathāgatas. Thus, this initial purification of the drop in the lalāṭa is believed to empower the initiate to actualize the Nirmāṇakāya of the Buddha. 5

The other two initiations, the Crown-pendant (patta) and the Vajra-and-Bell (vajra-ghaṇṭā) initiations, are designed to purify the drop in the throat-cakra by purifying the right and left nāḍīs. In doing so, these two initiations, which are performed at the southern gate of the kālacakramaṇḍala, are said to facilitate the purification of the initiate's speech-vajra and the actualization of the Saṃbhogakāya. The Crownpendant initiation is said to empower the initiate to attain the ten powers that are for the sake of attaining the ten perfections; whereas the Vajra-and-Bell initiation is said to empower the initiate to attain imperishable bliss by purifying the semen and uterine blood. 6

Likewise, the Vajra-Conduct (vajra-vrata) and Name (nāma) initiations, which are performed at the eastern gate of the kālacakra-maṇḍala, are designed to facilitate the purification of the drop at the heart-cakra, which is the mind-vajra, and the actualization of the Dharmakāya. The Vajra- Conduct initiation is said to induce the initial sublimation of the sense-faculties and their objects and to empower the initiate to attain the divine eye (divya-cakṣu) and other divine faculties. The Name initiation is believed to purify the faculties of action (karmendriya) and their activities and to empower the initiate to attain the four Immeasurables (brahma-vihāra). 7

Lastly, the Permission (anujñā) initiation, which is performed at the western gate of the kālacakra-maṇḍala, is designed to remove the defilements of the drop at the navel-cakra and to facilitate the actualization of the Jñānakāya. It is said to empower the initiate to set the Wheel of Dharma in motion.

In this tantric system, the initiate who has undertaken this initial purification of the body, speech, mind, and gnosis by means of the seven initiations is considered authorized to practice the sādhanas for the sake of the mundane siddhis (laukika-siddhi). 8 While receiving these seven initiations, the initiate takes the twenty-five tantric vows (vrata) and the pledges to avoid the fourteen root downfalls (mūlāpatti). In this manner, he increases his store of merit. 9 The power of merit that the initiate accumulates by means of the first seven initiations is considered effective in facilitating the attainment of the first seven bodhisattva-bhūmis, either in this life or in a future rebirth. If the initiate visualizes the kālacakra-maṇḍala while he is being initiated into it, then he accumulates enough merit to empower him to attain mastery over the seven bodhisattva-bhūmis in his present life. But, if the initiate who is free of the ten nonvirtues dies, he attains mastery over the seven bodhisattva-bhūmis in the next life. 10

2. The two higher initiations, the Vase (kumbha) and Secret (guhya) initiations, are designed to increase the initiate's ethical discipline that qualifies him to eventually attain permanent mastery over the other two bodhisattva-bhūmis, Acalā and Sādhumatī. In terms of the sexual yoga of Kālacakratantra practice, attaining Acalā (“Immovable”) entails the immovability, or nonemission, of semen; and attaining Sādhumatī (“Good”) entails the attainment of the mind of sublime bliss (mahāsukha-citta) during sexual intercourse. 11 Likewise, the other two higher initiations, the Wisdom and Gnosis initiations, are believed to facilitate the attainment of the tenth bodhisattva-bhūmi, Dharmameghā, which is described in this tradition as “the rain of sublime bliss that brings forth one's own well-being and the well-being of others, ” “the state of Mañjuśrī that removes the fear of cyclic existence. ” 12 These empowerments are said to be effective due to the power of the ethical discipline that the initiate accumulated during the two earlier higher initiations.

The four higher initiations are believed to empower the initiate to attain the remaining bodhisattvabhūmis by further purifying the habitual propensities of the previously accumulated impurities. In the course of these four higher initiations, the initiate engages in sexual union with an actual consort (karma-mudrā), experiences sexual bliss, and at the same time meditates on emptiness. At the same time, the initiate identifies himself with the Buddha's four vajras—the vajras of the body, speech, mind, and gnosis, respectively. Thus, in the Vase initiation, the initiate identifies himself with the bodyvajra, and he mentally offers to his spiritual mentor the young consort, the maṇḍala, and prayers. When the offered consort returns, the initiate gazes at the imagined consort, whom he visualizes as Viśvamātā, and imagines caressing her breasts. By doing so, the initiate brings forth the experience of bliss (ānanda), and while experiencing that bliss, he meditates on emptiness. This unified manner of experiencing bliss and cognizing emptiness during the Vase initiation is believed to facilitate the purification of the drop at the forehead-cakra and to further empower the initiate to attain the Nirmāṇakāya.

During the Secret initiation, the initiate identifies himself with the speechvajra and visualizes his spiritual mentor engaging in sexual union with his own consort. Subsequently, he visualizes that rays of light, which are emitted from the spiritual mentor's heart, bring all the deities of the kālacakramaṇḍala into the spiritual mentor's mouth. Those deities descend into the spiritual mentor's heart, and from there they arrive at the tip of his sexual organ, at which point, the initiate imagines the spiritual mentor placing a drop of purified semen into the initiate's mouth. The initiate gazes at the sexual organ of the consort and experiences sexual bliss, due to which the drop of bodhicitta from the throat-cakra descends into the initiate's heartcakra and causes the initiate to experience supreme bliss (paramānanda). While experiencing supreme bliss, the initiate meditates on emptiness. Thus, by unifying the initiate's experience of great bliss with his cognition of emptiness, the Secret initiation facilitates the purification of the drop in the throat-cakra and further empowers the initiate to attain the Saṃbhogakāya.

During the Wisdom initiation, the initiate identifies himself with the mindvajra. Here, the initiate enters into sexual union with the imagined consort (prajñāmudrā) whom he offered to his spiritual mentor during the Vase initiation. During the imagined sexual union, the initiate visualizes his sexual organ as a five-pointed vajra and the organ of his consort as light out of which arises a red lotus with three petals, with the yellow syllable phaṭ in its center. Due to this sexual union, the initiate experiences innate bliss (sahajānanda) as the drop of bodhicitta descends from the heartcakra into the navel-cakra. While experiencing this innate bliss, the initiate meditates on emptiness. Unifying the initiate's experience of bliss with his cognition of emptiness in this manner, the Wisdom initiation is said to facilitate the purification of the drop in the heart-cakra and to empower the initiate to attain the Dharmakāya.

During the Gnosis initiation, the initiate identifies himself with the gnosisvajra, and he identifies his consort with Viśvamātā. He enters into sexual union with the consort and experiences supreme, immutable bliss (parama-sama-sukha). Due to the experience of this bliss, a drop of bodhicitta descends from the navel-cakra to the tip of his sexual organ and remains there without being emitted. While experiencing the moment of supreme, immutable bliss, the initiate meditates on emptiness. In this manner, the Gnosis initiation facilitates the purification of the drop in the navelcakra and empowers the initiate to attain the Jñānakāya.

Thus, one may say that in the four higher initiations, it is the initiate's experience of the four types of bliss 13 and emptiness that induces the further purification of the four drops. In the Vase initiation, it is the experience of sexual bliss induced by the imagined caressing of the body and breasts of the consort; in the Secret initiation, it is the experience of sexual bliss induced by the imagined sexual union; in the Wisdom initiation, it is the experience of sexual bliss induced by the pulsation (spanda) of the tip of the sexual organ; and in the Gnosis initiation, it is the experience of sexual bliss induced by nonpulsation (niḥspanda) that is caused by passion for the mahāmudrā consort. In light of this, the four higher initiations themselves can be classified into the two types of path. The first two higher initiations can be characterized as the mundane, or conceptual, path, and the other two as the supramundane, or nonconceptual path. The four types of blissful experiences then are seen as the means by which these four initiations contribute to the removal of the habitual propensities of former mental obscurations and counteract their further emergence.

The initiate's progress through the eleven initiations is seen in the Kālacakra tradition as a symbolic representation of one's spiritual progress on the Buddhist path from a lay person to a monastic novice, to a fully ordained monk, and finally, to a Buddha. This symbolic progression is considered to be related to the initiate's empowerment to eventually attain the twelve bodhisattva-bhūmis. Thus, one who is initiated in the first seven initiations is referred to as a “lay Buddhist” (upāsaka), for he is predicted to attain the first seven bodhisattva-bhūmis. One who is initiated in the higher Vase initiation is referred to as a “novice” (śrāmaṇera), a “Buddha's son” (buddha-putra), or a “youth, ” since he is predicted to attain the eighth bodhisattva-bhūmi. Similarly, one who is initiated in the higher Secret initiation is referred to as a “fully ordained monk” (bhikṣu), “an elder” (sthavira), or “a crown-prince (yuva-rāja) of the Buddha, ” for he is predicted to attain the ninth bodhisattva-bhūmi. One who is initiated in the higher Wisdom and Gnosis initiations is referred to as a “Buddha, ” or “a teacher of the Dharma, ” since he is predicted to attain the tenth bodhisattva-bhūmi. 14 The four highest initiations empower the initiate to attain the remaining two bodhisttava-bhūmis.

This analogy of the progression through the eleven initiations to the progression from a Buddhist lay life to Buddhahood is one of many internal indications of the Kālacakra tradition's strong monastic orientation. This analogy is similar to the Sekoddeśa's analogy of the four higher initiations to the four stages of life—childhood, adulthood, old age, and Buddhahood. However, the Sekoddeśa draws its analogy on the basis of the experience of the four types of bliss during the four higher initiations, whereas the Kālacakratantra's analogy is based on the predicted attainment of the bodhisattva-bhūmis. Therefore, in the Sekkodeśa, one who is initiated in the higher Vase initiation is called a “child” (bāla), since he attains sexual bliss merely by touching the consort. One who is initiated in the higher Secret initiation is called an “adult” (prauḍha), for he experiences his bliss due to the imagined sexual union. One who is initiated in the higher Wisdom initiation is called an “old person” (vṛddha), for he experiences bliss caused by bodhicitta touching the tip of his sexual organ. Lastly, one who is initiated in the higher Gnosis initiation is called “the progenitor of all Protectors, ” “Vajrasattva, ” “a great being” (mahā-sattva), “Bodhisattva, ” “the nondual, ” “the indestructible, ” “the fourfold vajra-yoga, ” “Kālacakra, ” and so on, since his experience of bliss is caused by his passion for the mahā-mudrā consort. 15

The four highest initiations (uttarottarābhiṣeka) have the same names as the four higher initiations. They are said to induce the further purification of the four drops from their obscurations. In the four highest initiations, the initiate is given ten consorts, representing the ten powers (śakti), or ten perfections. As in the earlier Vase initiation, here too the initiate experiences sexual bliss by arousing sexual desire due to mentally gazing and caressing the breasts of a consort who is chosen from among the ten. Due to the aroused desire, a drop of bodhicitta descends from his uṣṇīṣa into the lalāṭa and gives rise to bliss (ānanda). During the other three highest initiations, due to the imagined sexual union with the remaining nine of the ten consorts and due to the retention of semen, he sequentially experiences supreme bliss (paramānanda), extraordinary bliss (viramānanda), and innate bliss (sahajānanda). As in the four higher initiations, which came earlier, here too the experience of the four types of bliss is accompanied by meditation on emptiness. Due to this, the experience is believed to further facilitate the transformation of the vajras of the body, speech, mind, and gnosis into the four bodies of the Buddha. 16 As with the preceding path of the four higher initiations, due to the experience of the four types of bliss, this fourfold path of initiation has both aspects: mundane and supramundane. In this way, the four highest initiations are the preliminary practices for the stage of completion.

In the four higher and the four highest initiations, the experience of the four types of bliss becomes the means of purifying one's own mental obscurations and facilitating the nondual vision of reality. As indicated earlier, the experience of sexual bliss is thought to exert its purifying power only when it is accompanied by both the retention of semen and meditation on emptiness. The following verses from the Ādibuddhatantra express this in the following manner:

- In the union with an actual consort (karma-mudrā) and in desiring a gnosis-consort (jñāna-mudrā), those who firmly hold the vows should guard their semen (bodhicitta), the great bliss.

- Upon placing one's own sexual organ into the vulva, one should not emit bodhicitta. Rather, one should meditate on the entire three worlds as the body of the Buddha. Due solely to that guarded [ bodhicitta ], Buddhahood, which is completely filled with the accumulation of ethical discipline and is fully endowed with merit and knowledge, comes about in this lifetime.

- The Samyaksambuddhas, who have attained the ten perfections, abide in the three times. By means of this [ guarded bodhicitta ], all Samyaksaṃbuddhas turn the Wheel of Dharma.

- There is no greater gnosis than this, which is the lord of the three worlds and is not devoid of emptiness and compassion for the sake of accomplishing its own well-being and the well-being of others. 17

Thus, already in the stage of initiation, one's own gnosis that manifests as both sexual bliss, or passion, characterized by seminal nonemission, and as the cognition of emptiness, or dispassion, acts as the means for actualizing the gnosis of imperishable bliss.

The Transformative Body of the Path of the Stage of Generation

The second phase of the transformative body of the path of actualizing the four bodies of the Buddha is the stage of generation (utpatti-krama). It consists of four main phases of practice, which are classified as the four types of sādhanas:

- 1. the generation of the body, or the supreme king of maṇḍalas (maṇḍalarājāgrī), which is specified as the “phase of worship” (sevāṅ (ga),

- 2. the generation of the speech, or the supreme king of actions (karmarājāgrī), which is specified as the “auxiliary sādhana” (upasādhana),

- 3. the yoga of the drops (bindu-yoga), which is characterized by the generation of the drops of semen and is specified as a “sādhana, ”

- 4. and the subtle yoga (sūkṣma-yoga), which is characterized by the arising of bliss and is specified as the “sublime sādhana” (mahā-sādhana). 18

This fourfold classification of the stage of generation corresponds to the fourfold classification of the Buddha's bodies, and it delineates the body of the path which is made up of progressively more subtle forms of tantric practice. The first two types of sādhana, which involve meditation on the fourfold kālacakra-maṇḍala and all its indwelling deities, are based on intricate mental imagery, which cannot be maintained without adequate meditative quiescence (śamatha). Moreover, the symbolic implications of the mental imagery sustained by meditative quiescence facilitate the contemplative's insight (vipaśyanā) into the empty and blissful nature of that imagery and its referents. Investigating the impermanent nature of the imagined deities of the kālacakramaṇḍala, and thereby realizing his own impermanence and the impermanence of all sentient beings abiding within the triple world, the tantric contemplative realizes that nothing in the kālacakra-maṇḍala or in the three worlds is of enduring essence. Therefore, on the stage of generation, the path of the purification of the four drops is uniquely characterized by the simultaneous development of quiescence and insight. This path is complemented by the practice of the meditator's self-identification with the visualized deities, or the cultivation of divine pride, which is necessarily based on some conceptual understanding of the emptiness of inherent existence of the deities with whom the contemplative identifies himself.

The visual formation of the kālacakra-maṇḍala is called “the supreme sovereign maṇḍala” because it corresponds to the generation of the four bodies of the Buddha. 19 When this mentally created, supreme, sovereign maṇḍala is conceived as the visual representation of the pure aspects of the contemplative's own gnosis, mind, speech, and body, it acts as the purifying agent of the meditator's four drops. The transformative power of the visualized kālacakra-maṇḍala is believed to lie in its efficacy to partially eradicate the obscurations of conventional reality (samvrtyāvarana), by allowing ultimate reality to manifest itself through the generated maṇḍala.

However, as indicated earlier, its purifying efficacy is believed to be contingent upon the contemplative's own understanding of emptiness. The Kālacakratantra asserts that one should engage in meditation on the kālacakra-maṇḍala only after one has understood that “the entire world is empty, ” that ultimately “there is neither a Buddha nor spiritual awakening. ” 20 The transformative power of this practice is also said to lie in the contemplative's understanding that the entire kālacakra-maṇḍala, which is a mere illusion (māyā) and an ideation (kalpanā), is nothing other than the manifestation of one's own mind. Accordingly, the contemplative must understand that in order to free his mind from ideation, he must eventually leave behind this form of practice and, in order to transform his mind into the actual Kālacakra, the unity of bliss and emptiness, he must engage in nonconceptual meditation. In light of this, the Kālacakratantra states:

- Because the entire sādhana of a vajrī is an illusion, o king, one should make one's own mind free of impurities; one should make it the lord of the maṇḍala. 21

On the grounds that the visualized kālacakra-maṇḍala is a mere mental construct that arises nondually with the meditator's own mind, one may say further that in this stage of practice the transformative agent of the meditator's four drops is his own mind.

1. In the first phase of the stage of generation, the method of purifying the four drops is characterized by the visualization of the kālacakra-maṇḍala and its diverse classes of deities, who represent the enlightened aspects of the meditator's body and of the cosmic body. As in the case of many Buddhist Mahāyāna meditational practices, here too, the confession of sins, rejoicing in virtue, taking refuge, and arousing the spirit of awakening (bodhicitta) precede the practice of meditative visualization. The path of the actualization of the four bodies of the Buddha on the stage of generation involves meditative practices during which the tantric adept imaginatively dies as an ordinary person and arises as the Buddha Kālacakra. For that reason, the stage of generation begins with a meditation in which the tantric adept mentally casts off his transmigratory psycho-physical aggregates in order to obtain the supramundane aggregates (lokottara-skandha). In this phase of practice, prior to visualizing the kālacakra-maṇḍala as the sublimated aspect of his own body and of the cosmic body, the tantric adept imaginatively dissolves the atomic structure of his own body and the body of the universe. In order to relinquish his habituated sense of self-identity and establish his new identity, the meditator mentally disintegrates his body in the same manner that the body dissolves by itself during the dying process. By meditating on the water-element, he eliminates first the fire-element; then when the earth-element has lost its solidity due to the absence of fire and it becomes liquid, he dries it up by meditating on the wind-element, which he disperses afterward into space. After that, he meditates on the space-element as the reflection of emptiness, or as empty form, which transcends the reality of atoms. 22 This manner of settling one's own mind on empty form and establishing it as one's true identity is a prerequisite for adequate meditative practice of generating oneself in the form of the deities of the kālacakra-maṇḍala. Whereas the first phase of the stage of generation is analogous to the stage of dying and the dissolution of the cosmos, the second phase of the stage of generation is analogous to conception in the womb and to the formation of the cosmos. It entails the mental generation of the four divisions of the kālacakra-maṇḍala as the mother's body and as the cosmic body. In this phase of practice, the tantric practitioner visualizes first the mind-maṇḍala, at the center of which is gnosis, which has the form of a lotus within the tetrahedral source of wisdom (prajñā-dharmodaya). In this way, he symbolically generates the Dharmakāya and the Jñānakāya of the Buddha, the sublimated aspects of the wind and earth maṇḍalas of the universe and of the mother's forehead and navel cakras. After mentally generating the mind-maṇḍala, the tantric contemplative visualizes the speech-maṇḍala encircling the mind-maṇḍala. By visualizing the speech-maṇḍala, he generates the Sa bhogakāya of the Buddha, t ṃ he sublimated aspect of the fire-maṇḍala of the universe and of the mother's throat-cakra. He further visualizes the body-maṇḍala encircling the speechmaṇḍala, and in this way, he generates the Nirmāṇakāya of the Buddha, the sublimated aspect of the water-maṇḍala of the cosmic body and of the mother's heart-cakra. Visualizing these four maṇḍalas of the gnosis, mind, speech, and body, together with their individual sets of four gates, portals, and the like, the tantric yogī mentally generates the sublimated universe and the mother's body, as well as his transformed environment, in which he will arise as the Buddha Kālacakra in the next phase of the stage of generation practice.

The following verses from the Ādibuddhatantra indicate the manner in which a tantric adept should understand that the maṇḍalas that he generates as the purified aspects of the mother's body and the cosmos are the symbolic representations of the Buddhahood into which he will arise as the Śuddhakāya:

- The maṇḍalas of the mind, speech, and body correspond to the Buddha, Dharma, and sublime Saṅgha. The four vajra-lines correspond to the four divine abidings (brahmavihāra).

- A quandrangular (form within the maṇḍala ] entirely corresponds to the four applications of mindfulness (smrtyupasthāna), 23 and the twelve gates correspond to the cessation of the twelve links [of dependent origination ].

- Likewise, the exquisite portals correspond to the twelve bhūmis, and the cremation grounds in the eight directions correspond to the Noble Eightfold Path.

- The sixteen pillars are [sixteenfold] emptiness, and the upper floors correspond to the elements. The crests correspond to the eight liberations, to the eight corporeals (rūpin), 24 and to the eight qualities. 25

- The face and the sides [of the gates] accord with the classification of the mind, speech, and body. The five pure colors correspond to the five: ethical discipline (śīla), and the like.

- The three fences in the maṇḍalas of the mind, speech, and body correspond to the three Vehicles, to the five faculties of faith, and the like, and to the five powers (bala) of faith, and so on.

- The pavilions in the three maṇḍalas correspond to the samādhis and dhāraṇī. The variegated jeweled strips of fabric correspond to all of the ten perfections.

- The pearl-garlands and the half [ pearl-garlands ] correspond to the eighteen unique qualities [of the Buddha) ( āveṇikā-dharma ). Bakulī flowers correspond to the [ten] powers. 26 The balconies correspond to virtues.

- [Balconies] filled with the sounds of bells and the like correspond to liberation through emptiness, and so on. Their state of being full of victory-banners corresponds to the [four] bases of supernatural powers (ṛddhi-pāda), and their glistening with mirrors corresponds to the [four] exertions (prahāṇa).

- The vibration of their yak-tail whisk corresponds to the [seven] limbs of enlightenment, and their decorative garlands correspond to the nine divisions [of the Buddha's teaching). The corners that are adorned with variegated vajras correspond to the four means of assembly (saṃgraha).

- Their being studded with the four jewels of [the Four Noble) Truths at the junctures between the gates and crests and always being surrounded by five great circles (symbolizes) the five extrasensory perceptions (abhijñā).

- They are surrounded by the vajra -chain of the constituents of enlightenment ( bodhyaṅga ) of one who knows all aspects, by a single wall of bliss, and by the light-rays of the gnosis vajra.

- The ever-risen moon and sun are in accordance with the division of wisdom and method. The pure mind, speech, and body are the Wheel of Dharma, the great pitcher, drum, tree of spiritual awakening, its wish-fulfilling jewels, and the like. This is a maṇḍala of splendid Kālacakra, which is the dharma-dhātu. 27

After purifying one's own perception and conception of the environment in this way, the tantric practitioner enters the next phase of the stage of generation, in which he imagines himself as an enlightened being arising in a pure environment. Therefore, this phase of the stage of generation is analogous to the individual's development in the mother's womb and to the origination of cosmic time. At this phase of practice, the tantric yogī generates the body of the Buddha Kālacakra as the sublimated form of the universe and of his own body by visualizing Kālacakra standing on the discs of the sun, moon, and Rāhu and emanating the five rays of light. This phase of visualization is analogous to the moment of conception in the womb. Thus, the sun, moon, and Rāhu represent the purified aspects of the mother's uterine blood, the father's semen, and the meditator's consciousness, which are joined in the purified mother's body that was generated earlier as the four maṇḍalas. The five rays of light symbolize the five types of gnosis, the purified aspects of the meditator's psycho-physical aggregates.

The next phase of visualization, which is analogous to the third month in the womb, represents the sublimation of the three links of dependent origination. In that phase, the meditator visualizes the Buddha Kālacakra standing in the ālīdha posture, 28 which symbolizes the flow of the prāṇas in the meditator's right nāḍī and their retraction in his left nādī. With his feet, the Buddha Kālacakra crushes the hearts of Rudra and Māra , the meditator's mental defilements. Here the tantric contemplative visualizes Kālacakra in union with Viśvamātā, the personified representation of the perfection of wisdom, or gnosis, who is standing in the pratyālīḍha posture, 29 which symbolizes the flow of the prāṇas in the contemplative's left nāḍī and their retraction in his right nāḍī. By visualizing Kālacakra and Viśvamātā, the tantric adept mentally generates the two aspects of the Buddha's mind: bliss and emptiness. According to the Vimalaprabhā, Kālacakra represents innate bliss (sahajānanda), or supreme, imperishable bliss (aksara-sukha); and Viśvamātā represents the gnosis of the emptiness that has all aspects (sarvākāra-śūnyatā-jñāna), which perceives the three times and is “purified by the elimination of the obscurations of conceptualizations (vikalpa) and the bliss of seminal flow (cyavanasukha). ” 30 Their sexual union within the pericarp of the lotus of the maṇḍala symbolizes the union of these two aspects of the Buddha's mind. The presence of these two deities in the heart of the kālacakramaṇḍala is to remind the meditator that gnosis, characterized by bliss and emptiness, is the ultimate nature of all other deities in the maṇḍala, that is to say, of all other aspects of Buddhahood and of the meditator's own psycho-physical constituents. In other words, all other deities in the maṇḍala are to be understood as the emanations of the two principal deities. For example, Viśvamātā, who is the perfection of wisdom, becomes Vajradhātvīśvarī for the sake of destroying ordinary hatred (prākṛtadveṣa) and bringing forth sublime hatred ( mahā-dveṣa ), which is the absence of hatred. She becomes Locanā for the sake of destroying ordinary delusion. Due to her sublime compassion, she becomes Māmakī for the sake of destroying ordinary pride, Pāṇḍarā for the sake of destroying ordinary attachment, and Tārā for the sake of eradicating ordinary envy, and so on. Likewise, Vajrasattva becomes Vairocana for the sake of illuminating the minds of deluded people, Amitābha for the sake of those afflicted by attachment, Ratnasambhava for the sake of generosity toward suffering beings, Amoghasiddhi for the sake of removing obstacles, and so on. 31 In this way, unified bliss and emptiness, symbolized here by the two principal deities in sexual union, free the mind from its obscurations by sublimating the elements that give rise to mental obscurations.

At times, the two principal deities are also identified with the contemplative's aggregate of gnosis (jñāna-skandha) and the element of gnosis (jñāna-dhātu), respectively; and at other times, they are both referred to as the element of gnosis that gives rise to the individual's mental sense-faculty (manoindriya). For this reason, they are also called “the gnostic deities” (jñāna-devatā). 32

The subsequent phases of the visualization of the deities accompanying Kālacakra and Viśvamātā are viewed as analogous to the further development of the fetus in the womb and to the sublimation of the remaining links of dependent origination. Thus, the tantric adept further visualizes the two principal deities surrounded by the eight goddesses who stand on the eight petals of the lotus and represent eight perfections. As he visualizes the other deities of the mind-maṇḍala—the four Buddhas and their consorts, the Vidyās, the deities with a tree and a pitcher (sataru-sakalaśā), the male and female Bodhisattvas, and the five male and female wrathful deities (krodhendra)—the tantric adept generates the sublimated aspects of his elements, sense-bases (āyatana), and other bodily constituents. The generation of the four Buddhas and their consorts and the male and female wrathful deities within the mind-maṇḍala is said to be analogous to the fourth month in the womb and to the sublimation of the fourth link of dependent origination. 33 Whereas the generation of the male Bodhisattvas is seen as analogous to the fifth month in the womb and to the sublimation of the fifth link of dependent origination or the six sense-faculties. The generation of their female consorts is analogous to the sixth month in the womb and to the sublimation of the sixth link of dependent origination.

In the schema of the fourfold kālacakra-maṇḍala, the gnostic couple, Kālacakra and Viśvamātā, who are the meditator's sublimated gnosis-aggregate and element, represent the Sahajakāya of the Buddha; all other deities of the mind-maṇḍala represent the Dharmakāya of the Buddha. The sequential visualization of the deities of the gnosis and mind-maṇḍalas illustrates the Kālacakra tradition's view of the Dharmakāya arising from the Sahajakāya as analogous to the arising of the sense-faculties and their objects from the elements. Accordingly, the Kālacakra tradition views the mental generation of the mind-maṇḍala as the sublimation of the meditator's conceptual and perceptual types of awareness. Every deity in the kālacakra-maṇḍala corresponds to the specific component of the human body or to its functions. Table 8.1 illustrates the manner in which the Kālacakra tradition identifies the six Buddhas and their consorts with the six elements, and the six male and female Bodhisattvas with the twelve sense-bases that arise from the six elements, respectively. 34

Upon generating this mind-maṇḍala, the contemplative generates the goddesses of the nāḍīs of time ( kāla-nāḍī ) within the speech- maṇḍala , in addition to the eight goddesses ( devī ) and their attending sixty-four yoginīs as standing on the eight petals of the speech- maṇḍala . The visualization of the eight principal goddesses and their retinue of yoginīs of the speech- maṇḍala is analogous to the seventh month in the womb and to the sublimation of the seventh link of dependent origination. By visualizing the goddesses of the speech- maṇḍala , the tantric adept generates the Saṃbhogakāya of the Buddha. 35

After visualizing the speech-maṇḍala, the meditator visualizes the diverse classes of deities of the body-maṇḍala: namely, the naiṛtyas, sūryadevās, nāgas, and pracaṇḍās. Visualizing the twelve naiṛtyas, the tantric practitioner generates the sublimated aspects of the twelve main nāḍīs of his body; and visualizing the twelve lotuses on which they are standing, he generates the twelve purified aspects of the cakras within the twelve joints of his arms and legs, which are called the action-cakras (karmacakra) and the activity-cakras (kriyā-cakra). Similarly, mentally creating the sūryadevas, the contemplative generates the purified aspects of the nāḍīs of his hands, feet, crowncakra, and anus. The generation of these two classes of deities, naiṛtyas and sūryadevas, is viewed as analogous to the eighth month in the womb and to the sublimation of the eighth link of dependent origination. Visualizing the ten nāgas and ten pracaṇḍās within the body-maṇḍala, the yogī generates the sublimated nāḍīs of his ten fingers and ten toes. This visualization is said to be analogous to the ninth month in the womb and to the sublimation of the ninth link of dependent origination. Visualizing the deities of the body-maṇḍala in this way, the contemplative generates the Nirmānakāya of the Buddha.

Just as all of the aforementioned deities of the four maṇḍalas symbolize the purified aspects of the four bodies of the Buddha that are latently present in the body of the fetus, so do they symbolize the purified aspects of the four bodies of the Buddha that are latent in the body of the individual born from the womb. The deities of the gnosis and mind maṇḍalas symbolize the four bodies of the Buddha latently present in the body of a young child; and the deities of the speech and body Maṇḍalas symbolize the actualized aspects of the four bodies of the Buddha that are present in the body of the individual. 36 Thus, by mentally generating the deities of the four maṇḍalas, the tantric adept imaginatively transmutes his entire life, from the time of conception until death, into the state of Buddhahood.

The Kālacakra tradition sees this entire phase of the generation of the body of Kālacakra as the fourfold kālacakra-maṇḍala as a meditation on perfect awakening with five aspects (pañcākāra-saṃbodhi); and it considers the following phase of upasādhana to be a meditation on perfect awakening with twenty aspects. 37

- 2. The upasādhana phase of the stage of generation practice involves a sādhana on the enlightened activities of the deities of the kālacakra-maṇḍala, that is, the activities of the four bodies of the Buddha. In this phase of practice, the tantric contemplative imaginatively awakens his consciousness, which has fallen into stupor and is unaware of its true nature, and he stimulates it to engage in enlightened activities. For example, he imagines the female consorts of the four Buddhas, who symbolize the four Immeasurables, the pure aspects of the four bodily elements, as standing in his four cakras and sexually inciting the Buddha Kālacakra, that is, his own mind- vajra , with

these songs:

- I am Locanā, the mother of the world, present in the yogī's seminal emission. O Kālacakra, arise with the nature of my maṇḍala and desire me.

- I am Māmakī, a sister, present in the yogīs' spiritual maturation. O Kālacakra, arise with the nature of my maṇḍala and desire me.

- I am Pāṇḍarā, a daughter, present in any man among the yogīs. O Kālacakra, arise with the nature of my maṇḍala and desire me.

- I am Tāriṇī, a wife, present in the yogīs' purity. O Kālacakra, arise with the nature of my maṇḍala and desire me.

- Protector of the world, whose intention is the deliverance of the world, upon perceiving the empty maṇḍala, expand the maṇḍalas of the body, speech, and mind. 38

Hearing their songs, one's own mind—the Buddha Kālacakra who is absorbed in emptiness—awakes, perceives that the entire world is like an illusion, and engages in activities for the benefit of all sentient beings. 39 This arousing of one's own awareness to engage in enlightened activities is closely related to the mutual union of the kālacakra-maṇḍala's female and male deities, which are the wisdom and method aspects, or the mind and body aspects, of the Buddha. The sexual union of the male and female deities, who belong to different families, is pertinent to the Kālacakra tradition's view of the ways in which the mutual pervasion of the four bodies of the Buddha gives rise to their enlightened activities. For example, the union of the deities comprising the Sahajakāya and the body-vajra gives rise to Kālacakra's body, just as their phenomenal aspects give rise to the body of the fetus. Likewise, the mutual pervasion of the deities representing the Dharmakāya and the speech-vajra is for the sake of teaching the Dharma, just as their phenomenal aspects within the body of the individual give rise to the prattling of a child. The union of the deities symbolizing the Saṃbhogakāya and the mind-vajra acts for the well-being of all sentient beings. The union of the deities who comprise the Nirmāṇakāya and the gnosis-vajra is said to bring about the liberation of sentient beings, just as their phenomenal aspects in the body of the individual give rise to the capacity for sexual bliss at the age of sixteen. 40

Upon generating the kālacakra-maṇḍala and all its deities in this way, the tantric adept performs a self-empowerment. He first purifies his bodily and mental constituents by invoking the deities that represent the vajras of the enlightened body, speech, and mind, and he requests the initiation from the goddess who belongs to the maṇḍalas of the body, speech, and mind. This imagined initiation is said to further purify the contemplative's cakras and facilitate the actualization of the four bodies of the Buddha. Thus, the eight divyās purify his eight-spoked heart-cakra and facilitate its transmutation into the Dharmakāya of the Buddha. The four Buddhas and their consorts, who are collectively multiplied by two due to being classified in terms of body and mind, purify the sixteen-spoked lalāṭa and facilitate its transmutation into the Sahajakāya. The six Bodhisattvas, their consorts, and the four krodhas, who become thirty-two when multiplied by two due to being classified in terms of wisdom and method, purify the thirty-two spoked throat-cakra and facilitate its transformation into the Saṃbhogakāya. Similarly, the sixty-four yoginīs purify the sixty-four spoked navel- cakra and facilitate its transformation into the Nirmāṇakāya. All other cakras in the joints of the contemplative's arms and legs, all the nāḍīs in the body, and the psycho-physical aggregates are purified by other deities of the kālacakramaṇḍala . 41 Upon imagining himself being initiated and purified in this manner, the tantric adept identifies himself with the body, speech, mind, and gnosis of all the Buddhas in order to further diminish his grasping onto his ordinary psycho-physical aggregates.

The two aforementioned phases of the stage of generation, the sevāṅga and upasādhana, constitute the Kālacakratantra's deity-yoga (devatā-yoga), which is believed to give mundane siddhis. Therefore, in this tantric system, a sādhana on the kālacakramaṇḍala is referred to as “a mundane sādhana” (laukika-sādhana). In light of the fact that meditation on the kālacakra-maṇḍala is a conceptual meditation that involves mental visualization and imagination, the Vimalaprabhā speaks of the first two types of sādhanas of the stage of generation as the sādhanas in which the object of meditation lacks duration, for it is characterized by origination and cessation. The kālacakramaṇḍala as the object of a sādhana is understood to lack duration in the sense that in the moment in which the tantric contemplative concentrates on the principal deity in the center of the maṇḍala, he is no longer aware of the other deities in the maṇḍala. Likewise, when the yogī concentrates on the blue face of Kālacakra, he is not cognizant of Kālacakra's red, white, and yellow faces, and so on. Since meditation on the kālacakra-maṇḍala is characterized by limited and momentary cognition, it is considered ineffective in directly inducing the state of nonconceptual and imperishable gnosis. From this vantage point, the Vimalaprabhā speaks of the sādhanas of the stage of generation as inferior sādhanas, which are designed for spiritually less mature practitioners. It comments in this regard:

- The Bhagavān, who knows reality, upon resorting to conventional truth in accordance with the power of sentient beings' inclinations, taught this truth as dependently originated gnosis —which is the domain of the dependently originated sensefaculties and is limited and capable of limited functions—to simple-minded people who are lacking in courage, who do not seek ultimate reality, whose minds are intimidated by deep and profound gnosis, who are satisfied with sādhanas for pacification and other such acts, who are attached to the pleasures of sense-objects and delight in the sādhanas for mundane siddhis, alchemy, eyeointment, pills, and the magic daggers. 42

On the one hand, the Vimalaprabhā acknowledges that there are inconceivable powers in this limited, conceptual meditation, along with the mantras, gems, pills, magical daggers, alchemical substances, and similar objects that are of limited functions. On the other hand, it affirms that the mundane knowledge and mundane siddhis that one acquires through the practice of conceptual meditation cannot perform the limitless functions of supramundane omniscience and the supramundane siddhi. 43 The limited knowledge and mundane siddhis do not bring about the omniscient language or supernatural powers (ṛddhi), because they are not free of mental obscurations. Therefore, the yogī who practices conceptual meditation is thought to be unable to bring about the well-being of all limitless sentient beings in the way that the Jñānakāya, which is free of coneptualizations, is able to do. Since the imagined Kālacakra-maṇḍala is a reflection of the contemplative's own mind, which is shrouded with obscurations, then the kālacakra maṇḍala is also a manifestation of the contemplative's mental obscurations. The Vimalaprabhā explains this in the following manner:

- When a phenomenon (dharma) that is with obscurations is made manifest, the yogī does not become omniscient; when a phenomenon that is free of obscurations becomes manifest, the yogī becomes omniscient. The omniscient one has the divine eye and ear, knowledge of others' minds, recollection of former lives, omnipresent, supernatural powers, the destruction of defilements (āsrava), ten powers, twelve bhūmis, and the like. He who meditates on the maṇḍala-cakra, on the other hand, does not become Vajrasattva who has ten powers, but destroying his path to omniscience and being overcome by false selfgrasping, he thinks: “I am Vajrasattva who has ten powers. ” 44

This assertion not only reveals the Vimalaprabhā's view of the stage of generation practice as inferior to that of the stage of completion, but it also suggests that the stage of generation can be detrimental to the realization of the ultimate goal of Kālacakratantra practice. Further analysis of the text indicates that this is the kālausing the maṇḍala, the contemplative's psycho-physical aggregates will actually become transformed into the aspects of the maṇḍala and will thereby directly cause Buddhahood. Therefore, the Vimalaprabhā also asserts that the contemplative cannot become a Buddha by the power of the generation stage practice alone and without the accumulation of merit and knowledge, just as a pauper who is devoid of merit cannot become a king by merely imagining that he is the king. 45 Although it denies the efficacy of the sādhana on the kālacakra-maṇḍala for eliminating all of one's mental obscurations, it never denies that it has certain purificatory powers, if practiced with the understanding that the imagined deities are not ultimate truth and that one's own impure body is not manifestly the pure body of the deity.

The deity-yoga of the stage of generation is followed by two yogic practices: the yoga of drops (binduyoga) and the subtle yoga (sūksṃa-yoga). The yoga of drops and the subtle yoga are designed to facilitate the purification of the four drops by inducing an experience of the four types of bliss. The yoga of drops directly induces the emergence of the drops of semen, and the subtle yoga induces the attainment of bliss caused by the flow of semen. The Ādibuddhatantra defines these two types of yogas in this manner:

- That which makes the ambrosia that is of the nature of semen flow in the form of a drop and that holds the four drops is called the “yoga of drops. ” That which, transcending any partition, is partless and holds the highest point of the four dhyānas is called the “subtle yoga, ” because it transcends [seminal] emission. 46

The practice of the two yogas involves a sādhana on sexual bliss with a consort who in this stage of practice is commonly an imagined consort, also called a “gnosisconsort” (jñāna-mudrā). According to the Vimalaprabhā, an actual consort is prescribed for simple-minded practitioners, an imagined consort for medially mature yogīs , and the mahāmudrā consort, who is implemented in the stage of completion, is prescribed for superior yogīs . 47

3. In the yoga of drops, during union with a consort, the contemplative visualizes himself as Vajradhara and meditates on the three worlds as being a reflection of the Buddha. Not emitting semen, he generates heat, called “caṇḍālī, ” in his navelcakra. Upon generating caṇḍālī, the contemplative imagines that in the left nāḍī of his navel-cakra, it incinerates the five maṇḍalas of the prāṇas, which are the phenomenal aspects of the five Tathāgatas, and that in the right nāḍī of the same cakra, it incinerates the prāṇas of the sense-faculties and their objects, which are the phenomenal aspects of the consorts of the five Tathāgatas. The incineration of the consorts of the five Tathāgatas implies here the cessation of activity of the sense-faculties, because the mind apprehends the dharma-dhātu. When caṇḍālī incinerates the consorts of the five Tathāgatas, semen begins to flow in the form of a drop. The drop of semen (bodhicitta) flows to the top of the head, and from there it sequentially flows into the throat, heart, navel, and secret cakras, bringing forth the experience of the four types of bliss: bliss (ānanda), supreme bliss (paramānanda), extraordinary bliss (viramānanda), and innate bliss (sahajānanda), respectively. When a drop of bodhicitta descends into the throat and melts there, it becomes the purified drop of speech (vāg-bindu); when it melts in the heart, it becomes the purified drop of the mind (citta-bindu); when it melts in the navel, it becomes the purified drop of gnosis (jñānabindu); and when it melts in the secret-cakra, it becomes the purified drop of the body (kāyabindu).

4. In the practice of subtle yoga, the drop of purified bodhicitta that descends into the secret cakra during the practice of the yoga of drops, now sequentially ascends into the navel, heart, throat, and uṣṇīṣa, bringing forth the experience of the aforementioned four types of bliss, which melt the atomic nature of the four drops and facilitate their transformation into the four bodies of the Buddha. 48 Thus, in the practice of these last two yogas, the path of the sublimation of the four drops is the path of the generation of sexual bliss, and the agent of sublimation is that very bliss. It is said that as the tantric adept purifies the drops of the body, speech, and mind in this manner, he also purifies the desire, form, and formless realms, which he previously imagined as the reflection of the Buddha. Mentally retracting the purified three realms with the light rays of his gnosis, or sexual bliss characterized by seminal nonemission, the tantric contemplative brings forth the gnosis of the three times (trikālya-jñāna). 49

The Transformative Body of the Path of the Stage of Completion=

The deity-sādhana of the stage of generation is viewed in this tantric system as characterized by ideation or imagination (kalpanā). As such, it is considered to induce directly the attainment of mundane siddhis and only indirectly to induce the attainment of spiritual awakening as the supramundane siddhi (lokottara-siddhi) or the mahāmudrā-siddhi. The preceding practices of the yoga of drops and the subtle yoga mark a transitional process from the stage of generation and its conceptualized sādhana to the stage of completion and its nonconceptualized sādhanas. The practice of the stage of completion is seen as the most pertinent to the attainment of spiritual awakening, for it is free of ideation and is uncontrived. It is free of ideation because it entails meditation on the form of emptiness ( śūnyatā-bimba ), or empty form, in which one does not imagine the deity's bodily form .

Thus, due to the absence of the yogī 's imagination of the bodily form, there is no appearance of empty form; and since the tantric yogī meditates on the empty form, it cannot be said that there is an absence of appearance of empty form. In this regard, the meditation on empty form is meditation on the nonduality of existence and nonexistence and on cyclic existence as devoid of inherent existence. In light of this, the Vimalaprabhā characterizes meditation on empty form as a nonlocal, or nonlimited ( apradeśika ), meditation since it is devoid of all mundane conventions. It also interprets this form of meditation as a tantric implementation of the Mādhyamika doctrine. 50 Therefore, it is considered here inappropriate for one who wishes to attain the supramundane siddhi to imagine the empty form—which is the universal form that has all aspects and holds all illusions—in terms of limited shapes, colors, symbols, and the like. In contrast to the sādhana on the kālacakra-maṇḍala , due to the absence of all conceptualizations, meditation on empty form is not characterized by the origination or cessation but by the absence of everything. Just as it excludes the visualization of Kālacakra and other deities, so does it exclude one's self-identification with Kālacakra. 51 Due to these characteristics, meditation on empty form is called the “ sādhana of supramundane reality” ( lokottara-tattva-sādhana ), the “gnosis sādhana , ” or the “ sādhana on the form of emptiness” ( śūnyatā-bimba-sādhana ). 52

Contrary to the sādhana on the kālacakra-maṇḍala, the gnosis-sādhana of the stage of completion is believed to lead to achieving the mahāmudrā-siddhi. The mahāmudrā is understood here as the perfection of wisdom, characterized by the absence of inherent existence of all phenomena, the source of all phenomena (dharmodaya), which is the Buddha-field, the place of joy (rati-sthāna), and the place of birth (janmasthāna). It is not a field of the transmigratory beings' attachment and aversion, nor is it an outlet of the ordinary bodily constituents, because it is the mind of imperishable time (aksarakāla), free of origination and cessation, embraced by the body that is free of obscurations as its wheel (cakra). It is said that whoever frequently and steadily meditates on this sublime emptiness, “the mother of innate bliss, who is a measure of the manifestation of one's own mind and is devoid of ideation with regard to all phenomena, and whoever embraces her, is called the omniscient Bhagavān who has attained the mahāmudrā-siddhi. ” 53 Thus, by practicing a sādhana on the mahāmudrā, one practices a sādhana on the ultimate nature of one's own mind; whereas by practicing the sādhana on the kālacakra-maṇḍala, one meditates on the conventional nature of one's own mind. These defining characteristics of conceptual and nonconceptual types of meditative practices are the most crucial factor in determining their soteriological efficacy with regard to their ability to provide one with the adequate accumulations of merit and knowledge. The Kālacakra tradition strongly affirms that just as the accumulation of merit does not take place without service to sentient beings, so the accumulation of knowledge does not take place without meditation on supreme, imperishable gnosis.

The practice of the stage of completion entails abandoning conceptual meditation, as well as sexual practices with the actual and imagined consorts. The union with either one of these two consorts is believed to induce perishable bliss only, the bliss characterized by pulsation ( spanda ). In contrast, union with the mahāmudrā consort, or the “empty form-consort , who is of the nature of a prognostic mirror and is not imagined, ” 54 is believed to induce supreme , imperishable bliss that is devoid of puslation ( niḥspanda ). 55

The gnosis-sādhana is divided into four main phases: worship (sevā), the auxiliary sādhana (upasādhana), the sādhana, and the supreme sādhana (mahā-sādhana). This four-phased sādhana describes the six-phased yoga (saḍ-aṅga-yoga) of the Kālacakratantra, which consists of the following six phases: retraction (pratyāhāra), meditative stabilization (dhyāna), prāṇāyāma, retention (dhāraṇā), recollection (anusmṛti), and concentration (samādhi).

The first two phases of the six-phased yoga, retraction and meditative stabilization, constitute the worship phase of the gnosis-sādhana. They are also called the “tenfold yoga, ” since by means of these two phases, the contemplative mentally apprehends the ten signs, including smoke, and so on. The subsequent phases of prānāyāma and retention constitute the upasādhana, which is characterized by perception of the subtle prāṇic body. The recollection phase constitutes the sādhana stage and is characterized by the experience of the three imperishable moments of bliss within the secret, navel, and heart cakras. Finally, the concentration phase of the six-phased yoga constitutes the mahā-sādhana, which is characterized by the unity of gnosis and its object and is accompanied by imperishable mental bliss. 56 These four categories of the six-phased yoga are said to correspond to the body, speech, mind, and gnosis vajras of the Buddha, or to his four faces in the kālacakra-maṇḍala, for they bring forth the manifestation of the four bodies of the Buddha.

On the stage of completion, the path of the purification of the four drops is characterized by meditation on the four drops. The final purification of the four drops takes place in the final phase of the sixphased yoga. Since the practice of the six yogas is believed to bring about the purification of the six aggregates—the aggregates of gnosis, consciousness, feeling, mental formations, discernment, and the body—it is interpreted in this tantric tradition as the way of actualizing the six Tathāgatas: namely, Vajrasattva, Akṣobhya, Amoghasiddhi, Ratnasambhava, Amitābha, and Vairocana.

The Six-Phased Yoga

The Kālacakratantra's ṣaḍ-aṅga-yoga begins with the manifestation of the mentally nonconstructed appearances of one's own mind, that is to say, the nighttime and daytime signs, and ends with the manifestation of one's universal form (viśva-bimba). In this way, the whole process of the ṣaḍ-aṅgayoga is a meditative process of bringing into manifestation the successively more subtle and more encompassing aspects of one's own mind.

1. The yoga of retraction (pratyāhāra) involves the meditative practice of retracting the prāṇas from the right and left nāḍīs and bringing them into the central nāḍī. In this phase of practice, the contemplative stabilizes his mind by concentrating on the aperture of the central nāḍī in the lalāṭa, having the eyes opened with an upward gaze called the gaze of the ferocious deity, Uṣṇīṣacakrī. As a result of that, the prāṇas cease to flow in the left and right nāḍīs and begin to flow in the central nāḍī . The cessation of the prāṇa 's flow within the left and right nāḍīs severs the connections between the five sensefaculties and their objects. Consequently, the five sense-faculties and their objects become inactive, meaning, the six types of consciousness cease to engage with their corresponding objects, and bodily craving for material things diminishes. This disregard for the pleasures of the body, speech, mind, and sexual bliss is what is meant here by worship. As the ordinary sense-faculties disengage, the extraordinary sense-faculties arise. Due to that, the ten sequential signs—the signs of smoke, a mirage, fire-flies, a lamp, a flame, the moon, the sun, the supreme form, and a drop—spontaneously appear; but these images are none other than appearances of one's own mind. As the contemplative's mind becomes more stabilized, the ten signs appear more vividly, and the contemplative's perception of external appearances diminishes. Wisdom and gnosis become the apprehending mind, and the ten signs, which are like an image in a prognostic mirror, become the apprehended objects. Thus, gnosis apprehends itself in the same way that the eye sees its own reflection in a mirror. This entering of the apprehending mind ( grāhaka-citta ) into the apprehended mind ( grāhya-citta ) constitutes its nonengagement with external objects.

The first four signs appear during the practice of retraction at nighttime or in a dark and closed space. Their appearance indicates that the prāṇas within the nāḍīs in the intermediate directions of the heartcakra have entered the madhyamā. The other six signs appear during the practice of retraction-yoga during the daytime and in open space. 57 A drop appears as the tenth sign with the form of the Buddha in its center. This Buddha is the Nirmāṇakāya, which is devoid of sense-objects due to its freedom from matter and ideation (kalpanā). Afterward, the yogī hears a sound that is not produced by any impact (anāhata-dhvani), which is the Saṃbhogakāya. The appearance of the first four of the six daytime signs indicates that the prāṇas within the nāḍīs in the cardinal directions of the heart-cakra have entered the central nādī; and the appearance of the last two signs indicates that the winds of prāṇa and apāna have been dissolved. Due to the spontaneity of this arising of the ten signs, the purified aggregate of gnosis (jñāna-skandha) is considered to be uncontrived or nonconceptualized (avikalpita). 58

The yoga of retraction is said to induce the state of Kālacakra and lead to the attainment of the body of Kālacakra by purifying the aggregate of gnosis (jñānaskandha). In terms of mundane results, such a yoga can accomplish a siddhi by which all one's words come true. This occurs due to the inactivity of the ordinary sense-faculties, which empowers the contemplative's speech with mantras.

2. The yoga of meditative stabilization (dhyāna) refers here to a meditative absorption on the allpervading form (viśva-bimba), which is also practiced with the gaze of Uṣṇīṣacakrī. It is designed to unify the five sense-faculties and their objects. Due to the tenfold classification of the sense-faculties and their objects as the apprehending subjects and the apprehended objects, meditative stabilization is considered here to be of ten kinds. It is also interpreted as a mind that has become unified with empty form as its meditative object and is characterized by the five factors of wisdom (prajñā), investigation (tarka), analysis (vicāra), joy (rati), and immutable bliss ( acala-sukha ). According to the Vimalaprabhā , wisdom here means observing the empty form; investigation means apprehending its existence; analysis implies ascertainment of that empty form; joy means absorption into the empty form; and immutable bliss is the factor that unifies the mind with empty form. 59 During the initial practice of the yoga of meditative stabilization, the ten signs, which appeared earlier during the retraction phase, spontaneously reappear. During the daytime yoga , the tantric yogī gazes at the cloudless sky either during the morning or afternoon, with his back turned to the sun, until a shining, black line appears in the center of the drop. Within the central nāḍī , the body of the Buddha, which is the entire three worlds, appears. It looks clear like the sun in water, and it has all aspects and colors. It is identified as one's own mind that is free of the sense-objects and not as someone else's mind, because it lacks knowledge of other beings' minds. Thus, in the sixphased yoga , one first perceives the appearance of one's own mind with the physical eye ( māṃsa-cakṣu ) of the Buddha, and at the culmination of the yoga , one perceives the minds of others with the divine eye of the Buddha.

The yoga of meditative stabilization is said to induce the state of Akṣobhya, for it purifies the aggregate of consciousness (vijñāna-skandha), and to induce the actualization of the five kinds of extrasensory perception (abhijñā). In terms of mundane results, it is believed to induce the experience of mental and physical well-being.

3. The yoga of prāṇāyāma is thought to be effective in unifying the ten right and left maṇḍalas by bringing the prāṇas into the central nāḍī. For this reason, it is said to be of ten kinds. In the practice of this yoga, the contemplative stabilizes the prāṇas within his navel-cakra by concentrating on the center of that cakra, which is regarded as the seat of the drop associated with the fourth state of the mind (turīya). In this phase of the yoga, the tantric adept practices the gaze of the ferocious being Vighnāntaka, directing his gaze toward the lalāṭa. During inhalation, the contemplative apprehends the arisen form of the Kālacakra's Saṃbhogakāya and brings it from his nostril into the navel, where Kālacakra and his consort merge with the drop. As the Saṃbhogakāya descends into the navel and merges into the drop there, the drop disappears, but Kālacakra and his consort remain in the navelcakra. During exhalation, Kālacakra and Viśvamātā rise above the level of the drop that has reappeared and ascend along the central nāḍī. When they ascend during pūraka, 60 the tantric adept concentrates first on the lower aperture of the madhyamā, wherefrom Kālacakra is brought into the navel; during recaka, 61 he brings it down into the lower cakra. Practicing in this way, the tantric contemplative brings the prāṇas into the navel-cakra and stabilizes them there. As a result of this, the external breath ceases, and the contemplative engages in the practice of kumbhaka. 62 After perceiving the Saṃbhogakāya, by means of kumbhaka, in the drop of the navel-cakra, he unifies the wind of the prāṇa that flows above the navel with the wind of the apāna that flows below the navel until a circle of the rays of light appears surrounded by his own body. After the contemplative stabilizes his mind on that drop in the navel-cakra, the abdominal heat (caṇḍālī) arises, melts the drop at the top of the uṣṇīṣa, and induces the experience of the previously mentioned four types of bliss. When the drop reaches the throat-cakra, the tantric adept experiences bliss (ānanda); when it reaches the heart-cakra, he experiences the sublime bliss (mahānanda); when it reaches the navel- cakra , he experiences the extraordinary bliss ( viramānanda ); and when it reaches the secret cakra , he experiences the innate bliss ( sahajānanda ). By melting the four drops, the caṇḍālī melts the afflictive and cognitive obscurations.

The yoga of prāṇāyāma is said to induce the state of Amoghasiddhi, for it purifies the aggregate of mental formations (saṃskāra-skandha); and in terms of mundane benefits, it is believed to purify the right and left nāḍīs by conveying the prāṇas into the central nāḍī, and it makes the tantric adept worthy of being praised by Bodhisattvas.