The Kali Practice: Revisiting Women's Roles in Tantra

The Kall Practice: Revisiting Women's Roles in Tantra

Loriliai Biernacki

-Parvati's question to Siva, Yoni Tantra

On the peaks of the holy mountain, Mount Kailas, the center of the world, the god Siva and his wife Parvati discuss the secrets of Tantric practice. In the middle of talking about a Tantric rite that involves worshipping a woman, the usually diffident and domesticated goddess Parvati asks her husband this curious question about women worshipping. "Should she herself worship the woman or should the male seeker [[[Wikipedia:worship|worship]]]?" (Yoni&Tantra, vs. 5.23. )The god's reply to the question is,

Theyoni,2 which makes up the whole world- jaganmayi- should be worshipped by the male seeker and the linga, the male organ, should be worshipped by her... By the mere worship of these two one becomes liberated while in the body(Yoni Tantra, vs. 5.23-5.25b).

Does a woman participate in worship or is she only the object of worship? If she does worship, what or whom should she worship? Parvati's question here presumes the worship of the yoni, that is, the worship of the female, as the normative practice. Her question seems to suggest that women and men, as equal actors in Tantric ceremonies, would perform the same normative ceremony of worshipping the yoni. So she asks if a woman participates in the Tantric ceremony the same way that a man does, where she would worship a woman.

Siva replies to the contrary, and the question disappears. The very question, however, signals that something is awry. Typically in Sanskrit Tantric textual sources, we find that women were the objects of male worship, but not worshippers themselves. Hindu Tantric texts generally assume a male perspective, male practitioners and a male audience, as we see in well-known texts like the Kularnava Tantra and the Kulacudamani Tantra.

In light of this general relegation of women to a passive role, Parvati asks an odd, even inconceivable, question. Are women, she asks, actors or agents in the Tantric context? In the heady Tantric quest for magical powers and enlightenment, do women themselves engage in ritual worship? Or are they merely passive objects, simply used by men in a male- dominated conquest for magical powers and otherworldly states?

Textually, we commonly see women represented in transgressive, "left-handed" Tantras as preeminently suppliers of potent fluids, menstrual blood, and conduits for male ecstatic (and enstatic) experience. David White in particular, compellingly argues for the position that women especially were the suppliers of fluids for "left-handed" Tantra (White 2003). On the other side, in the "right-handed" traditions, which do not employ liquor, meat or sexual rites, usually woman is displaced by the metaphor of feminine imagery. She is an inner principle, the goddess within the (male) practitioner. She is an energy, which rises up the spine of the practitioner to join in ecstatic unity with the God Siva in the practitioner's head. One sees the focus on women as an inner principle in esoteric, inner forms of "right-handed" worship, for instance, in much of the scholarship addressing the Abhinavaguptian corpus of Tantric texts.4 In this case, as bodied living females, women are absent.

The question, of course,& is&a&charged&one,&if&only&because&the&Tantric& proclivity&for&goddesses&has&been&on&some&fronts&understood&as&a&reclamation&of& feminine&power,&and&the&answer&to&whether&the&"Goddess&is&a&Feminist,"&to&borrow& from&the&title&of&an&important&exploration&of&this&topic,&is&one&that&that&can&and&will& be&used&by&feminists&today&in&creating&strategies&for&social&change.& This&chapter&addresses&the&theme&of&women&as&actors&in&Tantra.&I&suggest&that&a& particular form of Tantric practice, named the Kall Practice. presents a textual view of women we do not often see: one that acknowledges women's capacities for spiritual attainment-acknowledging women as practitioners and as gurus5 -- and recognizes the rights and wishes women may have in the daily business of living life.

Working with eight published texts associated with the Kamakhya temple and dating to the 15th-18th centuries, this chapter demonstrates the presence of an alternative view of women. This Kall Practice especially proposes a view of women which, I suggest shifts deeply engrained attitudes towards women to a position that grants women autonomous importance. Parvatl's question signals this shift. Her question jars us into considering the uncommon possibility that women may have actively participated in the Tantric rites described here, in ways that construed women as peers of men, rather than mere objects, and as having the same goals as men. In her question, Parvatl presumes that since the worship of the yoni leads to enlightenment for the male, the same will hold true for the woman. Her question asks us to reconsider how we have understood women's roles.

Siva's response, in any case, clearly affirms her suggestion that women functioned as actors. So, while women, at least in this roughly 15th-18th century text, do not seem to perform worship exactly as men do, Siva, nevertheless, goes on to emphasize women as active participants. Only by the worship of both- that is both men and women worshipping their respective opposite genders- does the prized attainment of enlightenment while still alive jvan mukti) occur.

Now, in reading Western scholarly literature on Tantra, one usually finds two salient arguments employed that mitigate against construing Tantric traditions as either affording or recognizing the agency of women. The first often runs: Yes, Tantrics venerated the goddess, but this veneration did not actually carry over into a veneration of actual living women. To examine this another way, at least literarily, the veneration of a goddess recognizes her capacity to effect events in a practitioner's life; one venerates a goddess precisely because she has power to make things happen and one seeks to win her favor so that she will choose to use her power to fulfill the desires of the practitioner. While this attitude assumes a sense of power and concomitant agency for the goddess from the standpoint of the believer, this sense of agency typically does not transfer to ordinary women. Neither does it typically transfer to the living woman who temporarily houses this goddess in a state of trance. She may be an incarnate goddess, but unlike the disembodied goddess, the ordinary woman is simply the object of veneration, not a subject or agent capable of choosing a particular course of action.

The second usually goes: Yes, women were necessary to the Tantric rite, but only as vehicles for male attainment. They were conduits of power, vehicles which males used to obtain especially potent magical powers. However, outside the limited sphere of the rite, their importance dwindled.6 In this view women's own attainment of spiritual power does not actually figure in the image of women.

These&views&certainly&accurately&portray&a&specific&body&of&Tantric&literature,& especially that produced several centuries earlier and in different locations than the 15th- 18th century texts I focus on here.7 However, we find here also an alternative view-including, for instance, an acknowledgement of women's special capacity to perfect mantras, and a reassessment of the status of women. This reassessment both extends to ordinary women and is not confined to the limited time and space of the rite.

It is important to stress that my sources are textual. So, to frame this use of textual sources, we should keep in mind that just as the Kall of the 21st century West is in some respects an imagined construction proliferating especially through written words on the internet, so what we address here are texts, and as such, simply claims by these Tantric writers about how one should respond to women. Given that this is the case, it is beyond the purview of the evidence to make claims regarding the actual historical behavior of actual women or male Tantric practitioners. We can only recover a semblance of the "what really happened" through the refractory lens of the text, and we also need to keep in mind that the views presented here only form one element in what is otherwise an unwieldy and often contradictory potpourri of practices and views in these texts.

In conjunction with this lack of other substantive forms of evidence of social practice, I use the terms "subject" and "agency" here not so much as a designation of some sort of "real," or existentially autonomous entity-certainly there are also considerable philosophical and cultural problems entailed in assigning these notions to a non-modern non-Western context. Nor do I use these terms to designate a sovereign, intact self which exists prior to any relation to a world outside itself. So, not so much about actual or historical subjects, I point instead to a textual portrayal that signifies a slippery but rhetorically something not present even in earlier Tantras such as the Kulacudamani Tantra (KCT) or the Kularnava Tantra (KuT), from which some of these eight texts borrow extensively, let alone in a more normative Hindu text like Manu's Dharma Sastra. This difference, which recognizes living women as venerable, may be read as representing a shift in attitudes towards women as a class. However, further than this, I make a different sort of argument than one which hinges upon the reconstruction of 17th century Tantric practice. Rather I suggest that we understand the Kall Practice as a form of representation of which the value lies perhaps most in terms of its historical value as a reference to the propagation of discourse. These texts reflect the emergence of a discourse addressing social relations between the genders, and I suggest that its importance lies in the challenge, as discourse, that it presents to normative classifications. For Western women today, Rachel Mcdermott notes that "the symbolism of Kall offers healing in a male-dominated world" (1996:291), a trend that she sees expanded on some fronts via the new internet culture (2003: 276ff) In a variety of ways this 21st century Western image of Kall appears constructed out of thin air. Yet, in an unexpected way, this use of Kall may not be entirely inconsistent with the advocacy of respect towards women that we find in the Kall Practice.

With this in mind, this essay also strives to propose an intersubjective engagement with these 15th-18th century texts. They offer us, in the 21st century West, unexpected ways of looking at gender--for instance the notion of woman as one among five categories instead of one among two. Specifically, I suggest these texts offer us today ways for rethinking our own categories of gender. In the rest of the essay, I first look briefly at what comprises the Kall Practice and at the texts that present the Kall Practice. Following this I address the notion of the gender binary and an alternative model also present in these texts. I then discuss elements of the Kall Practice as well as specific instances of women in venerable positions, women as proficient with mantras, and women as gurus. Finally I conclude with evidence that suggests the model for understanding the veneration of women in these texts finds a parallel in the veneration of the Brahmin.

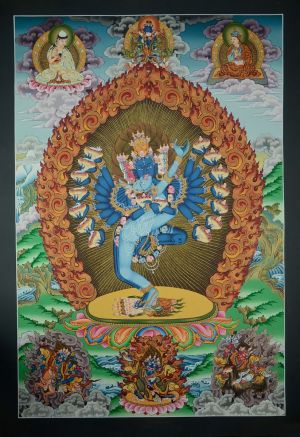

This particular form of Tantric praxis prescribing "left-handed" Tantric rites, including a particular focus on women, is named variously in the texts as the "Kall Practice." (Kalisadhana) the "Great Mantra Practice" (mahamantrasadhana) and the "Chinese Way," (cinacara) and rarely, the "Sakta Conduct" (saktacara). The “Chinese Way” is the most common expression used in these texts. This is not to suggest that this nomenclature in any way indicates actual Chinese practice. This last expression -cinacara- sometimes translated as the "Tibetan method" (Goudriaan 1981: 153)--looks suspiciously like a species of medieval "Orientalism" where a repressed exoticism and eroticism is, within official discourse, in the space of the written text, displaced and projected outward onto someone else, in this case onto the neighboring Chinese. We might find a contemporary example of this, in V.V. Dvivedi's 1978 Sanskrit introduction to the Saktisangama Tantra where he notes that the description of the “Chinese Way” (cinacara) approximates Muslim practice. He tells us, in Sanskrit, “here the Chinese bath and bowing resembles the action of namaz, [daily practice] following along with the Muslim religion.”8 For the sake of convenience I will refer to this practice throughout as the Kall Practice. This nomenclature is preferable to "The Chinese Conduct/Way" or "The Tibetan Way," even though the praxis is most frequently named this in the texts, since so much of Chinese and Tibetan Tantric practice does not in the slightest resemble this particular praxis and it would be confusing and misleading to label this practice with a contemporary national identity. The "Great Mantra Practice" and the "Sakta Conduct" are also not as frequently used to name this praxis as is Kall Practice, and since the essence of the practice revolves around the worship of primarily three female goddesses, Kall, the Blue Goddess of Speech, and Tara, taking this particular name from the texts captures the general impetus of the praxis best.

Five key elements make up the Kall Practice. I list these here below. Due to space constraints for this essay I will not be able to address all five,although I do address them elsewhere (Biernacki 2007).

1) The practice centers on women and stresses seeking out women and treating women with respect.

2) The practice is especially a mental practice; therefore, none of the ordinary rules for time, place or purity apply.

3) The Kall Practice is a rite that involves the worship of women, frequently incorporating the rite of sexual union, but at times simply limited to the worship of living women without including the rite of sexual union, particularly in the case of the worship of a young girl (kumaripuja), where sex is not included.

4) The praxis involved in the Kall Practice explicitly goes beyond the limited time and place of the rite. The attitude of reverence and respect towards women should be maintained constantly, twenty-four hours a day. I suspect this particular rule is especially important in ritually habituating an attitude, which shifts the position of women and the relation to women, in contrast to what we see in an earlier text like the Kularnava Tantra, where after the conclusion of the rite, normative hierarchies are reinstated, both with respect to gender and caste.

5) Finally, in the Kall Practice, the Goddess is viewed as embodied in living women. It is not simply that women who are worshipped in the rite are considered divine, but rather that women as a category are revered, whether worshipped individually or not. Further, as a category, women get assimilated to Brahmins. This last point in particular is structurally key to the shift these texts present for women..

Sources

The texts consulted for this study include especially the (l)Brhannila Tantra (BT), a long text published in 1984 and based in part on an earlier and shorter published version entitled the Nila Tantra (NT);9 and also, (2)Cinacara Tantra (CT); (3) Gandharva Tantra (GT); (4) Gupta Sadhana Tantra (GST); (5) Maya Tantra (MT); (6) Nilasaraswati Tantra (NST); (7) PhetkariniTantra (PhT); (8) Yoni Tantra (YT). They areall Sanskrit Tantric texts, that is, texts titularly self-identified as Tantras and containing explicitly Tantric elements also found in other Tantric texts, such as ritual prescriptions, discussion of the six Tantric acts,10 and an emphasis on mantras. They are also generally classified as Tantric texts in the extant scholarship (Goudriaan 1981, Kaviraj 1972). They present an uncommon attitude towards women typically not found elsewhere in classical Hindu texts such as, for example, Manu's Dharma Sastra and in Vedic Sanskrit texts11, and, for that matter, not common in a variety of other Tantric texts as well.

These texts also share a number of formal features, suggesting that we understand them in terms of a particular historical movement. Thy all are from approximately the same historical period and geographic region,12 Furthermore, they all include some mention of left-handed Tantra, i.e., specifically the inclusion of the five transgressive substances known as the 5 "m's,"13 including the use of liquor and a form of the rite of sexual union. Most of them consider the pilgrimage site of Kamakhya in Assam to be of preeminent importance. Additionally, one particular verse is replicated across several texts within this genre, but I have not come across the verse elsewhere either in general Hindu sources or in general Sakta sources, such as the Devi Mahatmya,14 or elsewhere among Hindu Tantric sources--and not even in much earlier Tantric Sources such as the Kulacudamani Tantra (KCT) or the Kularnava Tantra (KT), from which some of these eight texts borrow extensively. Given the verse's repetition across several texts, and given that many of these texts do borrow from older sources, what is probably most interesting is the singular absence of this verse elsewhere among older Hindu Tantric sources, and particularly its absence in other "left-handed" Tantric texts not from this time period. This verse reads, "Women are Gods, women are the life breath" and while the verse is not reproduced in all of the texts consulted here, it nevertheless encapsulates and nearly always accompanies, when it is found, the elements of the Kall Practice which we find in these eight texts. Also with some variation, and greater or lesser frequency the same goddesses keep popping up. Particularly important are Kall, Nllasaraswatl (the Blue Goddess of Speech) and Tara/Tarinl.

One more point of interest is that none of these texts have been translated yet into English, or any other European language, but all of them have been published. Several have been published multiple times; for instance, the Brhannila and its earlier version, the Nila Tantra, has been published five times since the 1880's, and the Gandharva&Tantra four times. That none are manuscripts suggests that at least for an indigenous audience they have been considered important enough to merit space on the printed page- and from a publisher's point of view, an expectation of an audience in India interested in buying these texts, an expectation voiced also in the eminent Tantric scholar V.V. Dvivedi's mention of the popularity (lokapriyata) of several of these texts (Dvivedi 1996: 1).15 Binaries

The dialogue between Siva and Parvatl presented above frames gender in terms of a binary. This model probably originally derives from the well-known classical cosmological and philosophical system of Samkhya, with its notion of male spirit (purusa) and female matter/Nature (prakrti). In the model here, male and female are two elements of a binary, and this notion of a binary pervades these texts. However, working against this notion of a binary, we also find inscribed within these texts a separate, different model of the relation of women to men, one that constructs women as comparable to a particular caste. In this case women are not the lesser member of a binary, but rather, women function as one group among several.

In some ways the notion of caste appears to be just as fundamental a division to Indian society as the gender divide. A contemporary anthropologist, Anjali Bagwe, titled a recent book, Of&Woman&Caste, where she draws from current colloquialisms that represent women as a caste group (Bagwe 1995: vi). Apart from this, a designation of women as akin to one of the castes is something we find elsewhere in Sanskrit texts, as early as the Vedas, where we find women lumped in with the lowest of the four castes, the servants (sudras) (Jamison 1996: 261). In the earlier, classical representations, the primary division among humans has to do with which caste one is. In this context all women and some men get grouped into this lowest class of persons, the servants. So in terms of ritual praxis, women are not treated as members of the caste to which their (blood) father or male guardian belong, but rather as a whole group they are treated as members of the lowest caste of males.

In contrast, the suggestion we find here instead is that women as a group form a separate caste apart from the lowest servant caste and that this special caste of women ought to be treated more like Brahmins than like servants (sudras). This grouping does not take into account differences between women, just as it does not take into account differences between Brahmins. In this configuration women as a separate class, like Brahmins, warriors, etc., possess innate capacities that elevate their status as a whole class. When a text extols women's competence with mantras and advocates respecting them, women here begin to move up, just as historically, redefining the collective identity of a particular caste subgroup facilitated an upward move along the continuum of the caste system for that group. Again, notably we find here that in certain respects, the treatment accorded women--as a class--at some places in these texts parallels that of the highest caste, the Brahmin.

From our own view in the 21st century West, perhaps the most salient element of this reconfiguration is that it affords a competing model of gender difference. While it certainly elides the no doubt real differences of status and wealth between different women, nevertheless, the presence of an alternative model, women as one group among several, presents an alternative to the nearly universal construction of women as the second sex, the perennially inferior member of a gender binary. So the view here is not like one particularly common and dominant view found in America, where the means of overcoming the gender binary is through an emphasis on the individual. In the American case the individual is of primary significance, and consequently, gender is a contingent and secondary category assigned to the individual, and one capable of being transcended. Indeed, it is frequently argued that we ought to transcend gender as a category in order to achieve the goals of equality. This blanket equality of the individual is a different model than the model of women as one group among several.

Nor is the difference that gender makes in this alternative model like a view often found in some forms of French feminism,16 modeled on a duality based on a gender essentialism, although, as I note above, we also find more commonly a binary model in these texts, encoding an essentialist gender binary. Neither do these texts propose a binary which then also allows space for a third neuter gender, though this is common enough in Indian texts elsewhere. Rather, in this particular alternative model, women are one group among five, which include Brahmins, warriors, merchants, servants and women. The groups are generally hierachically ordered with Brahmins at the top and servants at the bottom; women in this case form a fifth and are likened to the Brahmins, rather than being lumped in with servants.

Social classification often implies a social functionality, and this functionality typically encodes hierarchies of value. Setting women off as one group among several affords a reconsideration of their social functionality, and one that in this case shifts their social value, as a class. That the classification includes more than three is important because it tends to diffuse relationships away from an oppositional model, something that a number of scholars have noted (e.g., Prokhovnic 1999).

Both models, a binary and women as one category among several, operate throughout these texts, and a binary model is certainly much more pervasive in general. On the other hand, the presence of an alternative competing model helps to circumvent the familiar and inherent problematic dialectic of the binary, which unfolds as center and margin, self/other (male/female, mind/body, and so forth). The writers of these texts do not try to integrate these two different models. No authorial voice notices the disjunction between these separate models. They coexist without comment.

On the other hand, an alternative model of women as one of five groups offers ways of thinking about gender that a view of two precludes. It offers a view that by its contrast may shed light on our own 21st century understandings of gender. While this Indian model appears to still incorporate an essentialist model of women, which does not account for differences between women, nevertheless it does offer a move away from an idea of gender as a binary, which in turn affords a structural problematization of the idea of woman as the other of maleness.

A binary insinuates a structural pattern where normative (male) identity is established through the exclusion of what is not normative, that is, through the exclusion of female as a category. This entails definitionally a devaluation of the non-normative other; this devaluation is what founds the possibility of a valued normative identity. To put this another way, implicit in the structure of a binary is the notion that the two categories are opposed, and one of the two usually predominates. Further, implicitly the dominant category defines itself by what it is not, by what it excludes. This is one of the lessons Hegel so profusely iterated, that a binary implicitly incorporates an agonistic relationship. A multiplicity, on the other hand, diffuses the intensity of opposition (unless all the "others" are lumped again together, just as we see that the classical Hindu tradition lumps women and servants together). It may be that the stipulation of women as one class among a multiplicity (that is, they are comparable to Brahmins, but not lumped together with them) contributes to their greater valuation as a class of persons in these texts.

The Key: Women are gods

The Kali Practice. centers around women,both the worship of women and worship with women. Thus, the Gandharva&Tantra (GT) tells us:

Together with a woman, there [he should]reflect [on the mantra or practice]; the two of them together in this way [they do] worship. Without a woman, the practitioner cannot perfect [the mantra] at all. He should mentally evoke [the mantra] together with a woman and together with her, he should offer into the sacrificial fire as well. Without her the practitioner cannot perfect

[the mantra] at all. Women are gods; women are the life-breath (GT 35.54-GT 35.56).

Again we see in the Gupta&Sadhana&Tantra (GST), "Together with the woman, one should recite the mantra. One should not recite the mantra alone."&(GST&5.11.&) That the practitioner performs the practice with women--and here it appears women are doing the same things men are doing, contemplating the deity, saying the mantra, and making offerings into the fire-means that women play an important role in the practice.

Further, we should also note that the attitude of reverence towards women is inculcated outside the rite of sexual union as well and also towards all women, even women with whom one has no relations:

Having bowed down to a little girl, to an intoxicated young woman, or to an old woman, to a beautiful woman of the clan (kula), or to a contemptible, vile woman, or to a greatly wicked woman, one should contemplate the fact that these [women] do not appreciate being criticized or hit; they do not appreciate dishonesty or that which is disagreeable . Consequently, in every way possible one should not behave this way towards them.19

In this way the BT establishes a respectful attitude towards women, and in this context not just towards desirable woman with whom the male aspirant might perform the rite of sexual union, but towards all women, including a woman who is "kutsita," vile and contemptible, and whom one does not worship or engage in the rite of sexual union. At this point the BT iterates, "Women are gods, women are the life-breath" (BT 6.75). Now when does this contemplation happen? This bowing and this contemplation is what one does on a morning walk (BT 6.69-6.72, NST 11.116-11.122).21 The practitioner gets up in the morning and bows to the special tree of the clan. This particular bowing does not involve a mental visualization as does the next thing he does in the morning which is to visualize the guru. Hence, if we reconstruct his morning, he walks outside to the "clan tree" and then visualizes the guru and contemplates his main personal mantra. He then bows to the women in the quote above and then he reflects upon the fact that these women do not appreciate being lied to or hit, as we saw above. This part of the Kali Practice is also not connected with the performance of the rite of sexual union but is rather part of a habitual morning contemplation.

The worship gets extended further, even to the females of other species, of birds and animals. "The females of beasts of birds and of humans- these being worshipped, one's ineffective, incomplete deeds always become full of merit."22 What this does is to encode and highlight the female as a separate class. It also makes it clear that the rite of worship does not necessarily entail the rite of sexual union.

Also, one more point of interest, as the Maya&Tantra (MT) notes, is that the rite of sexual union that the Kali Practice prescribes is different from the infamous cakra&puja, the rite probably best known in the West as the "depraved" Tantric "orgy", where a group of men and women perform a ritual that includes feasting and orgiastic rites. The MT first describes the rite of sexual union connected with the Kali Practice. After the author finishes this description, the MT's author continues on to say, "now, I am going to tell you a different practice. Pay close attention. One should worship a woman who is the wife of another (parakiya)in the circle (cakra), and after this, [he should worship] his own beloved deity" (MT 11.17). The "cakra" or circle worship involves the wife of someone else chosen among the partners in the circle. This "circle" rite, which was simultaneously sensationalized and presented as a scandal, informed much of what was imagined in the West about Tantra (Dubois 1906: 286; Bharati 1975) For our purposes here, the scandal attached to the cakra& puja is not important, but rather that the spatial organization of these two rites differ fundamentally and as a result, the rhetorical effects of the rites, the "messages" they give, also differ.

In the cakra&puja, the participants are arranged in a circle and a centrally located altar instantiates the goddess. The goddess is invoked for the rite, usually into a pot of water, which is worshipped as temporarily housing her. So she is present in the rite, but present as separate from the participants, including the women participants. In the version of the cakra&puja that we find in the earlier KuT, in a carnivalesque fashion, the women are made to drink as the men pour liquor into their mouths (KuT 8.70); general drunkenness ensues. The “yogis dance, carrying pots of liquor on their heads” (KuT 8.71b). Then, “the yogis, drunk with wine fall down intoxicated on their chests; and the yoginls of the group, intoxicated, fall on top of the men. They mutually engage in the happy fulfilment of pleasure” (KuT 8.73-8.74).

In contrast, in the Kall Practice. there is not a group of women. Moreover, in the Kall Practice the woman is at the center of the rite, both spatially and ideologically. In this case, the living woman is&the goddess, not considered separate from the goddess. She herself is considered and worshipped as the goddess instantiated. And aside from the woman, only the person worshipping her is present.26 Spatially she takes the center, the place of importance, not the image of the goddess, and ideologically she is the center because she is the goddess. The ritual and spatial encoding of the two rites send different messages with respect to the status of ordinary women. In the cakra&puja, the woman is not particularly venerable and one can see how, for such a rite, it would be easy to view women as necessary tools during the course of the rite, who would then be unimportant after its conclusion. The rite described in the BT (6.20ff), on the other hand, inculcates a more psychologically durable reverence for the living woman who is worshipped.27 What is also important to recognize with this is that the practice of the rite of sexual union was by no means monolithic in its performance or function. Here, even one of our medieval sources points out that the rite had more than one version.

How is She a goddess?!!

Now a question arises: if the woman is worshipped as the goddess, exactly how is she the goddess? Does she get possessed by the goddess in the course of the rite? We might venture this, and elsewhere, apart from this particular Kall Practice this is likely the case. Interestingly, however, here the texts are explicit about precisely not viewing the woman as a medium for the goddess. "And there [in this rite] one does not do the invocation" of the goddess."28 This suggests that it is as a woman in her ordinary non-altered state, not when she is speaking in tongues, nor when some special external divinity empowers her, but that as herself, that she is divine. The difference between a rite which features the woman as a medium, possessed by the goddess, and a rite which considers an ordinary woman herself as divine is salient. If she is possessed, then this state is temporary and ultimately, not hers, not her own subjectivity. Here however, the point is to see a normal, non-possessed woman as divine.

In this context, the practice of constantly viewing women as goddesses starts to make sense. If a woman is the goddess only at a specific time, if only during the rite is she a medium for the goddess, then only at that time would it be necessary to treat her with the reverence due to a deity. There would be no need to maintain this attitude beyond the confines of the rite. On the other hand, if the divinity, which is the goddess, is intrinsic to her being, something she carries around with her all the time, something she is, then her status in general shifts. Then one would need to be vigilant, constantly maintaining an attitude of listening to her to make sure that the goddess standing before one will be pleased and therefore benevolent. It is precisely the act of looking to her, as ordinary woman, which affords a shift in the normative discourse between the genders and which allows for a recognition of her as a subject, as a person to whom one should listen.

This practice of listening to her is key. It doesn't matter how much other spiritual practice one does, because, as the MT says, "one's worship is in vain, one's mantra recitation is useless, the hymns one recites are in vain, the fire ceremonies with gifts to priests; all these are in vain if one does that which is offensive to a woman" (MT 11.34).

In addition the texts direct the practitioner to respect the rights of the bodies and minds of women. So as we saw earlier with the BT we also see elsewhere in other texts that the practitioner "should not treat hit women or criticize women or lie to women or do that which women find offensive"30 The GT and NST advise, "never should one strike a woman, with an attitude of arrogance, not even with a flower."31 Even further, the BT tells us, "not even mentally, should one harm a woman."32

Even if the practitioner feels that a woman has hurt him, or has violated his rights, the response should never be to harm her. "Even if she has committed an extreme offense, one should not have hatred for her. One should never hate women; rather one should worship women" (BT 7.111. Also, NST 16.7).

Now, this is not done out of a sense of superiority, in the sense of a chivalrous behavior towards women which accepts their offenses without striking back because women are the "weaker" sex. We might expect this because we are familiar with this attitude in the West. However, here it is exactly the opposite. One doesn't harm a woman, not because she's weak, but rather more like the reason one doesn't harm a powerful yogin or a sage like the cranky Durvasas. She has power, and she might get offended and then one had better be wary of her curse. So the NST tells us, "when a woman gets angry, then I [[[Siva]]], who am the leader of the pack, always get angry. When she [a woman] is upset or afflicted, that goddess who gives curses is always upset" (NST 16.11b-16-12a ). So if a woman is offended, she brings the ire of both the God Siva and the curse-giving dess on to the offender.

This shift in attitude is crucial, precisely because it sees women not as weaker but as stronger. She has power, power which, in itself, entails the prerogatives both of subjectivity and social clout. The disempowered may not have a voice, and the refinement of civilization commends the strong for taking pity upon the disempowered. And a chivalraic discourse, especially one easily recognized in the West, recommends treating women mildly for just this reason. On the other hand, here we have a different matter. In this case it is a different emotion than pity; it is fear which drives one to accept the offenses she may give.

Women and Their Mantras

Perhaps what's most important here, however, is the way that this power is coded. The MT tells us, "A woman who is engaged in practicing the Durga mantra is able to increase well¬being and prosperity, however if she gets angry at a man then she can destroy his wealth and life" (MT 11.33). What is key here is that the source of her power is her spiritual practice, the fact of her repetition of the Durga mantra (durgamantrarata). Like the yogin, and like the Brahmin, she has a power in her due to her spiritual attainment and her anger carries an edge. Just as the curse of the peevish Brahmin sage Durvasas sticks, so her anger will stick, whether one deserves the curse or not.

Now this is incredibly important because we see here an instance where women have power and it is not connected to their sexuality or to their capacity to be faithful to their husbands. These two types of feminine power are ubiquitous in South Asia, and one can see these two as part of a continuum. That is, a woman has a dangerous power in her sexuality, which, if tamed into a faithfulness towards her husband, as in the case of Kannagi (Holmstrom 1980), and notably also for the sati,36 can become a potent force for cursing, even for burning down a whole city- but here we have something quite different. That is, contrary to the normative coding of a woman as a sexual being and dangerous because of her sexuality--or because she's managed to effectively channel and bottle up her sexuality- here we have a perilous leap into a world where a woman is dangerous because, like the Brahmin priest, like the guru and like the yogin, she knows how to wield a mantra.

We also find that women as a class have a special ability to master mantras effortlessly. The BT tells us,

The restrictions that men contend with [in the practice of] mantras are not at all there for women. Anything whatsoever, by whichever [means], and moreover in all ways [is attained], for women magical attainment (siddhi) occurs, without any doubt... for a woman, by merely contemplating [on the

mantra] she in this way becomes a giver of boons. Therefore one should make every effort to initiate a woman in one's own family.37 The GT iterates this as well, "she doesn't have to do worship (puja), or meditate, or purify herself with a bath; just by merely thinking of a mantra women quickly get the power to give boons" (GT 35b-36a ). We discuss this more below in the context of women's initiation; here we can note that it is her gender, her status as a woman which entails this power, yet not her sexuality. Rather more like the Brahmin, who simply because he is born into the Brahmin caste, he has a tendency to tell the truth, as we see in the Upanisadic story of Satyakama Jabala, 39 so a woman, because of her status as woman, naturally can perfect a mantra. Similarly, persons by fate born into the caste of warriors have the capacity to endure pain, as we see in the well-known story of Karna with his guru Parasurama, who realizes that he is of the warrior caste despite his claim otherwise, because he can endure pain. Similarly, simply being born a woman, that is, woman as a species, affords this facility with mantras (Biernacki 2007).

Women as Practitioners, as Gurus

We also find women in an uncommon role in these texts: as gurus and as practitioners. With this, women are accorded subjectivity through a recognition of their spiritual competence. Now, we do find evidence in contemporary Western scholarship that women play key roles in Tantra today, even taking the esteemed role of guru. The data is readily available and clear in modern and contemporary anthropological studies (Erndl 2000 :92; Shaw 1994 ), especially in anthropological evidence focusing on modern saints like Anandamayi Ma. We find evidence for this also from the 19th century, in the case of Ramakrishna's Tantric guru, the Bhairavi and Gauri Ma (Anderson 2004: 65-84), also from the 16th century in the case of Slta Devl (Manring 2004: 51-64). We also see this in Assam in the 16th century where we find two women, Kanaklata and Bhubaneshwari, who become leaders of Vaisnava groups, in the role of gurus for the groups (Barpujari 2004: 236-237) Here we find this also in our Sanskrit Tantric texts associated with the Kall Practice.

We will look first at the Blue&Goddess&of&Speech&Tantra (NST). The NST presents women as gurus in a casual way, which suggests that something is ubiquitous and taken for granted. The NST tells us the appropriate honorific endings to tag onto the name of one's guru and gives the endings for a male guru and for a female guru "The male gurus who give all magical attainments have 'lord of bliss' attached to end of their names. If the guru is a woman, then 'mother' is attached to the end of her name" (NST 5.70). Without any fanfare, this text assumes that women function in that most esteemed of roles, as guru, and the text's reader ought to be aware of the proper ending for the guru's name.

In the Gupta&Sadhana&Tantra (GST), more is made of the notion of a female guru. After the God Siva gives the visualization of the male guru, the Goddess Parvatl responds,

The initiation given by a woman is proclaimed to be auspicious and capable

of giving the results of everything one wishes for, if, from the merit accumulated in many lives and by dint of much good luck, a person can acquire a woman as guru. Oh lord, what is the visualization of the woman guru? Now I want to hear the visualization one uses in the case of a woman guru. If I am your beloved, then tell me.41

Siva gives the visualization,

Listen, Parvatl, overflowing with love for you, I will tell you this secret, which is the visualization of a woman guru, where she is to be meditated upon as the guru. In the great lotus in the crown of the head on a host of shining filaments, is the female guru, who is auspicious (siva). Her eyes are like the blossoming petals of a lotus. She has firm thick breasts, a thousand faces,42 a thin waist. She is eternal. Shining like a ruby, wearing beautiful red clothing, wearing a red ring on her hand and beautiful jeweled anklets, her face shines like the autumn moon adorned with bright shining earrings. Having her lord seated on her left side, her lotus hands make the gestures of giving boons and removing fear. Thus I have told you, oh Goddess, this supreme meditation on the female guru. It should be guarded strenuously. It should not be revealed at all (GST 2.21- 2.26).

A number of elements are similar in both the visualizations of the male and female gurus. For instance, both their faces shine like the autumn moon, and they both have eyes like lotuses. They both have the same hand gestures, of giving boons and the gesture of removing fear, and they both have on their left side their partner. Also, the practitioner meditates in both cases on the guru as being located in the crown of the practitioner's head.44 The visualization of the female guru takes an extra verse, and this extra verse includes the description of her red clothing and ruby ring.

This visualization of the female guru and its source text, the GST, was also well known enough for Ramatosana Bhattacarya to cite this visualization in his well known Sanskrit compendium on Tantra, the Pranatosini in 1820. In this context he also cites a hymn from the Matrkabhedatantra, which gives the "armor" of protection (kavaca), sung to the female guru as well as a hymn which is the "Song of the Female Guru" (Striguru Gita) from the KankalamaliniTantra. 45 Interestingly, the hymn to the female guru apostrophizes the female guru as the Goddess Tarini, a goddess strongly associated with the Kali Practice and the hymn is mythically sung by Siva to Tarini. That this female guru is not simply the wife of the male guru, who, because she is his wife, also receives worship, Ramatosana makes clear by including a few pages later the specific form of worship which one offers to the wife of the guru (Ramatosana Bhattacarya 2000: 479). This separate praise of the female guru who is precisely not the guru's wife is important because it indicates a female authority not dependent upon or derived from a male relative.

Moreover, that it is the goddess Parvati who takes the time to frame the insertion of the visualization of a female guru also deserves attention on our part. It suggests a reflexive self-consciousness on the part of this section's author. The author is aware of the relative rarity of the female guru and yet chooses to gloss the fact that we do not frequently see female gurus as a sign of the general lack of attainment of the practitioners. It takes many lives of good deeds, as Parvati says, "the merit acquired from many lives," (GST 2.19) and most people simply do not have this "right stuff." We may read this as a species of historical revisioning found in the 17th century, but in any case it highlights a vision of women that does not denigrate them but rather elevates them.

In this context it is a female, the goddess Parvati, who asks for the visualization of a female guru, suggesting that it might be women who would articulate the need for this type of representation, and further, that women are able to speak for women.

Even considering that Parvati is a goddess, nevertheless, two other things need to be taken into account. First, in the Indian context the line between gods and humans is not so rigid, and certainly not rigid to the degree that it is in the West. Secondly, since in this context women are goddesses embodied, and vice versa, it makes sense to read this preeminently as a woman speaking in this context--and especially so since, of all the goddesses, Parvatl tends to be one of the most docile and domesticated, a saumya (benevolent)&goddess, not noted for her independence from a dominating male spouse. In this sense she stands as a good representational figure for the role that the majority of ordinary women in the Indian context play, i.e., not independent from their husbands. Furthermore, that we see a woman speaking up for women-indeed a woman praising the power and efficacy of a woman guru-hints at a sense of solidarity among women. Women can exist in relation to other women, not in competition for male favor. They are capable of promoting the status of women in general. Elsewhere I have written about a reference to a woman as the initiating guru in the Rudrayamala, so I will not address this here (Biernacki 2007). &

Now, what does it mean for women to be gurus? The guru holds spiritual authority as well as authority in the social and public sphere. The guru also represents a moral authority, a voice in the lives of his or her followers, which is construed as looking to the interests of the followers. The inclusion of women into this space of public authority, I propose, is part of the same configuration that enjoins the worship of women. That is, it is not an accident that the same texts which propose the Kall Practice also take for granted the presence of women as gurus. The fact of women in this position both signals a marker of an increase in status on public and social levels for women, at least for these writers, and further catalyzes a process which acknowledges the competence that women possess, and by dint of their intrinsic nature, ought to possess.

It is not just that women figure as gurus; they also figure all the way down, suggesting that not just exceptional women were accorded respect, but ordinary women as well. We find references to the process of initiating women, to women as practitioners, and to the exceptional facility with mantras that women as a class possess. So, we find that "one should make every effort possible to initiate the women of one's clan, one's family (kula)."46 Indeed, this act of initiating women is a great blessing for the family, and it will affect future generations. "Whoever does this auspicious act [of initiating women]-- in this lineage are born men equal to Brhaspati. There is no doubt about this. This is the truth, this is the truth, oh Goddess" (BT 7.199b ). Brhaspati is the guru of the gods and noted for his learning and eloquence. So it is interesting that initiating a woman will not bring sons who will become emperors or great warriors but rather sons who will be learned.

The Key Again: Women Are Gods !

Earlier I mentioned a particular signature half-verse that is repeated across several texts and that signals a rescripting of the view of women. "Women are gods; women are the life-breath" the verse proclaims.48 Since women are gods, it makes sense to both honor women and to construct an ethic in relation to them whereby one does not offend them, in other words, to treat a woman as one treats a god. And indeed we find that this innate and divine power that women have is profound. Women are, after all, like gods, since as the Gupta Sadhana Tantra (GST) tells us, "women are the source of the world, women are the source of everything, oh Goddess" (GST 1.9a ). With this statement the GST assimilates women as a class to the level of creator deity, which may partially help to explain their apotheosis into divinity. The innate and divine power women possess is so great, in fact, that in the Blue Goddess of Speech Tantra (NST) and the Maya Tantra (MT) women head the list of gods and god-like figures to whom one owes allegiance, even displacing the great gods Siva and Visnu.

Thus we see that the NST advises one to sooner abandon one's mother and father and even one's guru, rather than to insult one's female partner. "Better to abandon one's mother and father and one's guru... than that one should insult one's beloved (fem.)" (NST 16.12b-16.14a ). This, in fact, precisely inverts the common Hindi proverb that Gloria Raheja gives us: “Whoever kicks [i.e., offends] his mother and father to strengthen his relationship with his wife, his sin will not go away even if he wanders through all the pilgrimage places [where sins are said to be removed]” (Raheja and Gold 1994 : 121).

In contrast, in the&Blue&Goddess&of&Speech&Tantra (NST), Siva says:

Better to abandon Brahma, Sambhu and Hari, better that I (Bhairava) myself be abandoned, than that one should insult one's beloved (fem.). One's worship is in vain, one's mantra recitation is useless, the hymns one recites are in vain, the fire ceremonies with gifts to priests; all these are in vain if one does that which is offensive to a woman (NST 16.12b-16.14a).

If one insults a woman, then all one's spiritual endeavors are useless. In this instance one can imagine this playing out on the domestic front- a husband all wrapped up in his spiritual quest, worshipping the gods while his wife tries to get him to take care of her and the family's needs (the husband protagonist in Deepa Mehta's Fire (1998) comes to mind). In our scenario here, this wife would have a scriptural injunction to back her case. Siva, however, goes further than this; he continues, "it is better to die than to do that which is offensive to a woman" (NST 16.15).

The MT offers the same advice as the NST, and then goes even further. Here, not only are the male gods second fiddle, and one should give up one's life rather than insult a woman, but more than this, even the goddess is relegated to a secondary position. "Better even that one should abandon the Goddess (Devi); but one should not in any way abandon one's own beloved female partner" (MT 11.36b ). The MT also supplies the rationale for prioritizing one's female partner:

Not the creator, not Visnu, not Siva, not the beautiful Goddess, not the

primeval eternal Goddess-none of these [[[gods]] or goddesses] will be able to protect the person who does that which is offensive to women.( MT 11.37f ).

So women are accorded this respect because intrinsically they are gods, "striyo devah.” However, it is rather curious that the texts all use the masculine word "god" (deva). That is, women are gods and not goddesses. Elsewhere in these texts in profusion, women are assimilated to goddesses. For instance Siva says to the goddess, women are "in their essence, you" (GT 35.8: tvatsvarupini ) using the feminine form. Why are they here in the Kall Practice indicated by the masculine term "god"?55!

I'm going to suggest that the use of the masculine here is a linguistic marker referencing another class of gods, and that as a class of gods, women resemble this other class of living breathing gods. That is, the status that we find for women in these texts in many respects parallels the bhu-deva, the "earth-gods”, i.e., Brahmins, that class of humans who are like gods, but walk the face of the earth.

This is corroborated in other ways; for instance, the GST applies the same procedure of feeding Brahmins for the attainment of religious merit to women. "Earlier the rules were given that one should feed a Brahmin according to one's ability. In the same way one should feed a woman" (GST 5.9bf). Women are like Brahmins, and just as feeding a Brahmin brings merit, so does feeding a woman. Similarly, the BT also tells us that worshipping a woman brings results equal to that which one gains by giving a learned Brahmin a field rich with grain (BT 6.7f). Elsewhere, in a list where we might expect to find Brahmins listed, women take their place. The CT says "one should make great efforts and with devotion worship the guru, goddess, sadhus (itinerant practitioners), women, and the immortal self" (CT 5.7). It would not have been at all against normative expectations to find Brahmins in this fourth position slot; instead here we find the category "women." Again, the GST describes for each of the four castes the state of beatitude one can expect from the repetition of the mantra associated with the five m's.56 Here, the Brahmin is absorbed into the supreme self; the warrior caste (ksatriya) gets to dwell with the Supreme Goddess eternally; the merchant attains the same form as the supreme Goddess (svarupa); the servant caste (sudra) gets to live in the same general world as the Goddess (saloka). The text then includes women as a fifth caste, who get absorbed into the body of the Goddess (GST 7.15ff).57

The point of interest for us here is that women are marked as a class, like Brahmins, like the other three castes. They function as a category, just as Brahmins function as a category. One should not harm women as a class, because women are a class. Like Brahmins who should also not be harmed because they are earth-walking gods (bhu- devah), women are also a class of gods who happen to be walking on earth. And again, just as we find in normative Hinduism that serving Brahmins, these earth-walking gods, leads a person to salvation, so similarly, all "beings reach salvation by serving women" (CT 4.23b ; 2.44-Adhika Patha ). Earlier I noted a verse from the GST that assimilates women as a class to the creator god. In fact, this is precisely what we find with Brahmins who get linguistically and otherwise assimilated to the creator god Brahma.

This class action reverence is not at all like the respect accorded to the guru or the yogin. In the case of the guru especially, most Tantric texts, including these, are eminently cognizant of the existence of both good and false gurus, and take no pains to supply us with lists of the qualities we might expect to see in both. Gurus are individuals and individually merit worship and respect. Not so the case with Brahmins, and here with women. Just as Brahmins as a class are categorically offered respect, so these texts enjoin this sort of class based respect towards women. We should keep in mind here how radically this diverges from normative Hindu tradition where women as a caste are mostly lumped in with, or place on a par with the lowest of the four castes, the sudras (Smith 1991: 18).59 Likewise, women's facility with mantras extends to members of the class as a whole and not specifically to particular women.

What does this class action reverence mean for women? It affords a way for shifting the status women have in the social sphere. For our own purposes, what's interesting about this is precisely that it does not rely especially upon a version of gender founded on a duality. This non-binary model, I suspect, is part of what's key in the reconfiguring of women's roles. A dualistic model one could argue, implicitly structures itself around a notion of self and other which inevitably encodes an agonistic model, which by its very form as duality resists reconciliation. It may be that, as Kristeva and Lacan argue, that in so far as we construct our sense of self out of an element which must be extruded outside and alienated as "other" to our selves--and as an other which has historically taken the form of woman, as both Lacan and Kristeva note (Lacan 1998: 6, 11, 73; Kristeva 1982) -this

"other", as a perpetually alienated "other", then becomes and remains intrinsic to the stability of self. That is, we can't rid of the "other" without destabilizing our sense of self. This indeed presents a formidable psychological barrier to seeing women as equal, to releasing them from the category of "other." On the other hand, the model which these texts present offers one possible way out of the impasse we find with the binary self/other (echoed in the binary of man/woman). The very multiplicity of the terms destabilizes the system. This may offer possibilities for rethinking gender outside a dualist hierarchy.

2 The word "yoni" here may refer to the woman or it may refer to the female sex organ, though in this case, the reply appears to suggest that it refers to the sex organ.

4 See for instance, Muller-Ortega 1989.

5 Dimock's (Dimock 1989:215-216) research on the Sahajiyas in the Bengali region in the 15th-17th centuries supports the claims for women's roles as teacher I make here.

6 David White's analysis (White 2003) is probably one of the best representations of this view, but his is not isolated. See also Agehananda Bharati (Bharati 1965 (1993 repr): 304ff) and Davidson (Davidson 2002: 92ff, especially 97). White, in particular, admirably pays attention to historical shifts and nuances in the use of Tantric sex, contrasting, for instance, the view of the Kularnava Tantra and other Kaula texts with Abhinavagupta's school; although his examination of texts has tended to exclude the group of texts I examine here. See also Humes, (Humes 2000).

7 And it differs from some contemporary anthropological research (i.e., Humes 2000, and Caldwell 1999).

8 I give here also Dvivedi's original Sanskrit for this quote since this is such a striking claim he makes: “ityatra varnitau cTnasnananamaskarau islamadharmanuyayinam vaju-namaj-karmanT anuharatah” (Dvivedi 1978: 42).

9 Edited by Rasik Mohan Chattopadhyaya in Tantrasara, (1877-84) Calcutta, a text to which I did not have access.

10 The satkarman, a term referring to the sixfold division of goals in Tantric praxis.

11 For information on attitudes towards women in Vedic Sanskrit texts, see for examples, especially Jamison 1991 and 1996:Patton 2002; and Smith 1991.

12 The Gandharva Tantra differs from the other sources in that it strongly affiliates itself with the SrT Vidya tradition and has less association with the Northeastern region. I discuss the dating of these texts elsewhere (Biernacki 2007).

13 The "5 m's" --each of the words in Sanskrit begins with the letter "m"--include meat (mamsa), fish (matsya), liquor (madya), parched grain (mudra), and sexual intercourse (maithuna).

14 Notably many of these texts reference the DeviMahatmya and some, such as the Maya Tantra 3.12-3.20 directly quote the Devi Mahatmya. However, nearly all of these texts date much later, to probably not earlier than the 16th century, suggesting a late date for this signature verse. I discuss the dating and location elsewhere (Biernacki 2007). The Gandharva and Phetkarini Tantra are both cited in Brahmananda Giri's Saktanandatarangini, suggesting an earlier date for these two texts, especially for the Gandharva Tantra which Brahmananda Giri cites extensively. The verse is discussed below.

15The Cinacara Tantra presents an exception, since there is a German translation of it. See References below. Also, I heard of a popular non-scholarly English translation of the Cinacara Tantra, but was not able to track it down.

16 Luce Irigaray is probably one of the best examples of the articulation of this model (see especially Irigaray 1985), though its proponents are numerous.

19 BT 6.74-75: NT p.28, ln.14, also BT 6.300, NST11.120-11.121, CT 2.23, MT 11.38. Literally the second line says: "hitting them, criticizing them, dishonesty and that which is disagreeable to them--in every way these are not to be done"- balam va yauvanonmattam vrddham va kulasundarTm II kutsitam va mahadustam namaskrtya vibhavayet I tasam praharo ninda va kautilyamapriyam tatha II sarvatha ca na kartavyam "

21 See Biernacki 2007:40-41 for the Sanskrit and translation of this passage.

22 BT 6.301-6.302. See also BT 6.57.

26 The guru may optionally be present, and it appears was probably a necessary presence when the couple first began performing the rite. See YT 1.19.

27 I discuss this durable reverence in detail elsewhere (Biernacki 2007).

28 CT 3.16; again at YT 1.16. The Sanskrit for CT 3.16 is: tatra cavahanam nasi The line in the YT is identical (shifting slightly in the next portion of the verse). The emphatic use of the verb Jas in these cases emphasizes that this runs counter to a more usual practice of possession. Hence my italics for "not" is actually marked in the text, as the use of the verb Jas is reserved mostly for when one wishes to add emphasis.

30 CT: 2.24: tasam praharo nindanca kautilyamapriyantatha II sarvatha ca na kartavyam I; CT 2.24, NST 11.121, NT p.28, ln.14, BT 8.91 as well as BT 6.74, GT 35.9, NT p.9, PhT 11.17 for no hatred towards women and GST 5.17-5.20 cautioning the practitioner to worship and feed women, and if one out of anger or delusion neglects to worship women, the practice is useless.

31 GT 35.8a : kadacid darparupena puspenapi na tadayet I, NST 16.7: sataparadhasamyuktam puspenapi na tadayet. As I discuss (Biernacki 2007), this line in the NST, though not that in the GT, is lifted from KuT 11.95.

32 BT 6.300.The line here continues, "especially not the women who are his."

36 See especially Lindsay Harlan's interesting discussion of the cursing power of the sati (Harlan 1996).

37 BT 7.188: niyamahpurusairjneyo na yositsu kadacana II yadva tadva yena tena sarvatahsarvato

> pi ca I yositam dhyanamatrena siddhayahsyur na samsayahll ... yosiccintanamatrena tathaiva varadayinT I tasmat sarvaprayatnena dTksayet nija kaulikTm Here "siddhi" is plural, but for the sake of syntax I translate it as singular, "magical attainment."

39 Chandogya Upanisad 4.4.3ff (Olivelle 1998).

41 GST 2.18-2.20 We should also note here that Siva initially does not want to reveal the visualizations to ParvatT because women's natures are wavering, and they might tell the secret. GST 2.9b

42 A variant reading the editors give here is prasannavadanam, "a smiling face."

44 The verses giving the visualization of the male guru are GST 2.12-2.15. I discuss this in greater detail elsewhere (Biernacki 2007:48-49).

45 Ramatosana Bhattacarya 2000: 473; and for the hymn of "armor" and for the song sung to the woman as a guru (strTgurugTta, Ramatosana Bhattacarya 2000: 475ff; for the wife of the guru, sapatnikagurupujanam, Ramatosana Bhattacarya 2000: 479. This stotram in the KankamalinT

Tantra (TripathT 1996: 3.27-3.34) is not framed in this text as a hymn to a female guru, but rather as a hymn to ParvatT as the guru.

46 BT 7.198; and also GT 36.2. See also NST 14.50. 48 CT 2.25, NST 11.122, NST 16.6, GT 35.56, BT 6.75b, BT 8.90. The Sanskrit here is "striyo devahstriyahpranahstriya eva vibhusanam": "Women are Gods; women are the life-breath; women in this way are a splendor, a beauty." "vibhusanam" alternatively means "ornament". NST 16.6 reverses the word order with "striya< (sic) pranahstriyo devahstriya eva vibhusanam".

55 We should also note here that the text uses the term "god," rather than the feminine abstractive devata, which tends to carry a diminished importance in relation to the term deva. In this context see also Weinberger-Thomas (1999: 172) for a contemporary instance of women, in this case, the sat, designated with the male term dev (the Hindi version of the Sanskrit), rather than the female form devl. 56 The pancatattva in these texts usually refers to the 5 m's discussed earlier. However, it may also refer to the five elements or five principles of the cosmos.

57 This reading comes from two manuscripts the editors titled "k" and "n". Recension "g" also lists women as a fifth group, though here they do not get absorbed in the body of the Goddess. The editors printed an alternative version that lists the fifth category as "army generals" (apparently the "kha" manuscript). Now as far as the logic of categories go, it seems rather far¬fetched to list the four well-known castes and then as a fifth add the category of "army generals"--given that three of the five manuscripts give the fifth category as women. This editorial decision likely reflects an uneasiness on the part of this text's editors and one of this text's redactors to the more symmetrical idea of women as constituting a fifth caste. Also, "army generals" as a category is generally subsumed under the warrior caste. Finally, given that what the fifth caste obtains, absorption into the body of the Goddess (devTdehe pralyate), it appears rather more likely that women would attain this state than would army generals.

59 See Smith 1991: 18. We should note also GST 11.13 where women are still conceived of as a group like the four castes, however here rather than treated more like Brahmins, they again get lumped together with Sudras, as prohibited