“From one perspective, the six-syllables are the name mantra of Chenrezik. From another, Chenrezik is a bodhisattva who embodies the great compassion of all the buddhas and incorporates their bodhichitta and activities as well as all of their power. This means that his mantra has the potency of what are known as truthful or powerful words. His strength and commitment to help others was inconceivable and so the benefits of his mantra, these words of truth, are wondrous.” – Karmapa

![]()

Contents

Happiness and Suffering

Creating the causes for happiness

Who is Chenrezik?

Correctly understanding the bodhisattva

The Preliminaries

Refuge, Bodhicitta, and how to visualize Chenrezik

The Background of the Practice

A history of the sadhana by Thangtong Gyalpo

Meditating on the Deity

How to correctly meditate during the practice

Reciting the Mantra

The stages of reciting the mantra

The Meaning of Om Mani Padme Hung

Six different ways of understanding Chenrezik’s mantra

Bringing Activity on the Path

How to meditate after concluding the practice

Dedication of Virtue

Dedicating the merit of the practice

![]()

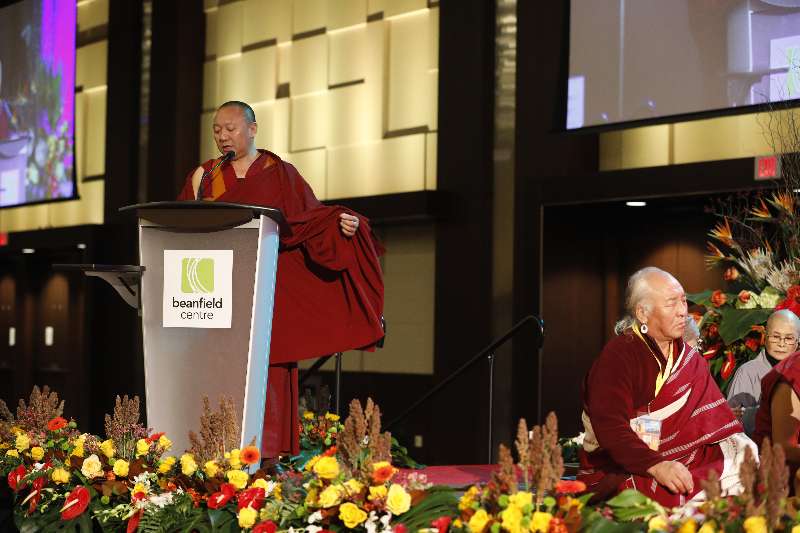

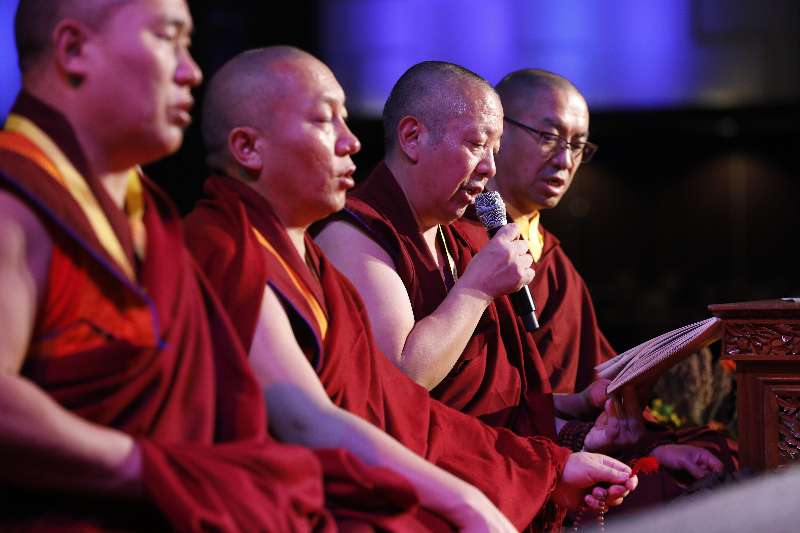

Session One, Refuge and Bodhicitta

Beanfield Centre, Toronto, Canada on October 27, 2018

The Karmapa warmly welcomed all who had come from near and far to the teaching and acknowledged all the effort and expense they had made to be in Toronto. He expressed his great disappointment in not being able to come himself, explaining that when he was about to depart, his doctor advised him that, given his physical condition, he should not board a plane at this time. He was extremely sorry not to be in Toronto with everyone; however, he was inspired and delighted to teach so that people are not left empty-handed.

He commented, “It’s also true that you have gathered here to hear the teachings of the Buddha and not so much to see me. In order that the genuine Dharma continue, I wanted to teach here to day on the topic we had chosen, the practice of Noble Chenrezik known as ‘the All-Pervading Benefit of Beings.’ I will explain it briefly for those who wish to practice.”

Happiness and Suffering

“In general, all living beings, not just humans,” the Karmapa continued, “are the same in that they seek happiness and wish to avoid suffering. We are all like travelers on a large ship, and we could be old or young, rich or poor, beautiful or not. No matter how different our physical forms might be from the outside, we are all the same on the inside: our feelings of happiness and suffering are the same and our wish for happiness and our desire to avoid suffering are the same. Like all the passengers on a boat, the path we are following and the goal we seek are identical.”

However, we have a problem. The Karmapa explained, “We may wish for happiness but we do not know its actual cause, and therefore, do not seek it out. We may wish to avoid suffering but do not know what causes it.

“The main difficulty is that we want happiness but do not know its cause nor how to create it. We wish to be free of suffering but do not know its cause or how to remove it. We encounter difficulties because what we wish for and what we practice contradict each other: seeking superficial happiness, we create the causes for our own suffering. From another perspective, you could say that what we want is not in harmony with the way things actually are.

“For example, we get sick and do not want to be ill but we do not know the cause of our disease, and so the result—this painful suffering—does not cease. And merely wanting to be free of suffering is not enough.

“If you compare human beings with animals, humans know what to take up and what to give up,” the Karmapa explained. “Humans have the ability to distinguish between good and bad, which animals lack. For this reason, humans have the possibility to create what the texts call ‘a precious human birth.’ This means that we have not just attained a human body but also the wisdom that knows how to distinguish between what to adopt and what to reject. This is what makes for a precious human birth.

“Simply being born a human does not guarantee that we will make our lives meaningful as a precious human birth. For a human birth to be come meaningful means that in line with our wish to be happy, we know how to create the cause of that happiness, virtuous actions; in line with our wish not to suffer, we know how to give up negative actions. If this happens, then we have a precious human birth that accords with the meaning of the term.

“Actually, ‘a precious human birth’ has two meanings: the key points are first knowing what to adopt and reject, and then knowing how to do this. We want happiness and not suffering, but merely seeking what we want and do not want does not benefit us. We need to know which causes to take up and which ones to reject. We are all aware of the good results we want but we are ignorant of their true causes. It is crucial that we learn to correctly deal with the causes of happiness and suffering. This is why Buddhist treatises teach extensively about what to adopt and what to reject—it is the key point.”

Who is Chenrezik?

“Today, the topic is the practice of Chenrezik,” the Karmapa began. “In general, among mahayana Buddhists, whether Tibetan or Chinese, there is not one follower who has not heard of Chenrezik. Many people think of Chenrezik as a deity but who is he really? Chenrezik is widely known as a bodhisattva; however, if we speak of Chenrezik as a practice, how do we understand this figure? If we look at his name, it refers to the one who gazes with eyes of love and compassion on all beings in the six realms of samsara. He is continually concerned about and wishes to protect every living being. We can say then that the practice of Chenrezik is one of love and compassion.

“Many people understand the practice of a deity to be supplicating them, prostrating and making offerings to them. But actually, this kind of practice that sets the deity apart from us and makes them into a separate entity to be the object of our actions is not the true practice of the deity. The real practice of Chenrezik is one that develops within our being the qualities of love, compassion, and altruism. We are able, for example, to speak kindly to others and benefit them. This is the actual practice of Chenrezik, and we should begin with this foundation in mind.

“Lacking this understanding and just doing the sadhana, reciting the mantra, and counting the numbers will not benefit us. When someone asks us, “Who is Chenrezik?” it is not enough if all we can reply is, ‘Chenrezik is a bodhisattva with four arms.’ We should be able to respond, ‘Doing the practice of Chenrezik means developing our love and compassion, and giving rise to bodhichitta. Accomplishment means being able to manifest the level of Chenrezik.’ This is the kind of understanding we should have. Before we do any practice, it is essential that we look into the correct view and how to hold it.

The Practice of Refuge and Bodhicitta

“There are many short and long sadhanas of Chenrezik composed in Tibet and many have been translated from Sanskrit into Tibetan. From among all of these, we are looking at the practice written by the Siddha Thangtong Gyalpo (1361-1485) known as ‘the All-Pervading Benefit of Beings.’ The instructions on how to practice this sadhana are divided into sections. The first one is the preliminaries that include going for refuge and generating bodhichitta; this is followed by (2) the main part, meditating on the deity; (3) reciting the mantra, and so forth.

“The two parts of the first section, refuge and bodhichitta, are held in high esteem in Buddhist texts. Why? Because whether or not you have taken refuge determines whether or not you are a Buddhist. Whether you are on the mahayana path or not is measured by whether or not relative bodhichitta is present in your being. Both of these points are essential. Whether we are a Buddhist or not comes down to taking refuge; whether we are on the mahayana path or not, comes down to having bodhichitta. Refuge and bodhichitta provide the very foundation of our practice.

Going for Refuge

“How to understand going for Refuge? To state it simply, we take refuge in the Three Jewels, the Buddha, Dharma, and Sangha. To apply the metaphor of the path, the Buddha is the guide who shows the path to take, the Dharma is the path to take, and the Sangha is the group of people who accompany us along the path. To apply the metaphor of being sick, the Buddha is like a doctor, the Dharma is like medicine, and the Sangha is like our caregivers. These examples can open our understanding through the different perspectives they offer.

“The Buddha has been famous for over 2,500 years as the guide, explaining to us, ‘If you are looking for full awakening, here’s the path of practice you should take.’ The path is the Dharma, the way that leads to liberation or omniscience. While we are traveling that path, our companions who help us on the way are the Sangha.

“If we look at these three in this present time and ask, ‘who is the Buddha’s representative now?’ It is the authentic spiritual friend, who shows us an unmistaken path. The Dharma is the advice and key instructions the friend gives that lead us to enlightenment. The Sangha are those who sustain us with spiritual or material support. We need all three of these Jewels: If we are sick, we need a doctor to diagnose, medicine to heal, and caregivers to support us.

“Going for refuge, therefore, is not just pronouncing some words but stepping forward and engaging in activity. We think, ‘My teacher, you have given me guidance and I will put it into practice.’ We think of this person as a guide we should follow, someone capable of giving good counsel and worthy of respect. We need to recognize that their advice is exactly what we should be practicing and that the Sangha is the group of people who support our virtuous activity. Just pronouncing the words is not enough.

Awakening Bodhichitta

“The second key point is bringing bodhichitta to life or awakening bodhichitta. On the relative level, this is the resolve, the dedicated effort, to bring all living beings to buddhahood. It could also be defined as the mind that is turned toward benefiting others. Having this bodhichitta determines whether or not we are on the Mahayana path.

The teachings often present a greater and a lesser path. What mainly differentiates the two is a higher or lower view, a more vast or narrow perspective. If we consider the definitive meaning, the view is that of emptiness. ‘A vast or narrow view’ refers to a mind that is broad and spacious or quite limited. In the realm of practice, there are several ways to understand the scope of mind; basically, it refers to the range of responsibility that we can take on. If we can assume an immense responsibility, we belong to the mahayana (the greater vehicle). If we are confined to a smaller responsibility, we belong to the hinayana (the foundational vehicle). The greater and lesser paths, therefore, are distinguished by the amount of responsibility we can carry.

“Differentiating levels of awakening bodhichitta, therefore, depends on our minds. We have to look into ourselves to see how much the courage (literally “strength of heart”) we have. This is not something we show to others in the same way that we might exhibit our wealth or fame. It is not a question of what we are displaying on the outside, but of how we really are on the inside. We must turn and look into ourselves to see if we actually have this type of courage, ‘Can I really take on this responsibility?’ If we find that we can, we are on the Mahayana path; if not, we have not yet arrived.

“Discussions about the preliminaries often deal with gauging their importance. Some think that because they are preliminaries, they are not very important, but this is mistaken. The preliminaries are essential and should be deeply anchored within us. They are the very basis of practice. When we are building a house, the greatest expense is for the foundation. With a very stable basis, a house will remain a long time. If the basis is not stable, the house will be unsteady and soon collapse. This is why the Kagyu tradition teaches that the preliminaries are more profound than the main practice.

“The Kadampa scriptures state that if we do not comprehend the preliminary practice of death and impermanence (the second of the Four Thoughts that Turn the Mind), Guhyasamaja practice will not be profound or powerful. Comprehending death and impermanence eliminates the need for complex practices like Guhayasamaja. All we will need are the words of refuge—such is its immense importance.”

Visualizing Chenrezik for Refuge and Bodhicitta

The Karmapa then turned to the next stage of the practice, the visualization. “We begin,” he explained, “by imaging that in front of us is a brilliant white cloud and the space surrounding it above is filled with rainbows and many brilliant lights, among which are arrays of beautiful flowers. In this most pleasant environment, we imagine our root lama inseparable from Chenrezik, present not as an ordinary person but as the essential nature of the three supreme ones, the Buddha, Dharma, and Sangha. We visualize a single bodhisattva but actually, Chenrezik is the embodiment of all the buddhas and all the bodhisattvas of the ten directions. We imagine that he is present before us and gazing at us with compassion.”

“We are surrounded many people: those whom we are fond of, those with whom we do not have close relationships, and those whom we find difficult or off-putting. Beyond these groups, all living beings—without distinguishing between friends or enemies—are gathered around us. We might feel that we do not have a good relation with them or perhaps none at all, but in terms of our shared nature, we all seek happiness and wish to avoid suffering. It is as if we all belonged to the same family, so we image all of us together. We are not alone; everyone wishes to be happy and free of suffering. Imagining all this, we supplicate Chenrezik asking for the power to benefit others as he does. Placing one hundred percent of our hopes in him, we recite the refuge prayer.

“Some people find it difficult to imagine a deity such as Chenrezik. In my opinion, however, this is not the most important aspect if the practice. What is important is that we have the feeling that Chenrezik is nearby and present just as a person might be, and also that all living beings (friends the same as enemies) are nearby and surrounding us, sharing our wish for happiness and well-being.”

The Karmapa then recited the well-known text for refuge and awakening bodhichitta:

In the supreme Buddha, Dharma, and Sangha,

I take refuge until attaining full awakening.

Through the merit of practicing meditation and mantras,

May I attain buddhahood for the benefit of all living beings.

The first two lines refer to taking refuge and the Karmapa commented, “When we take refuge, it is not the numbers of repetitions that count but the way we are thinking. In the line, ‘In the supreme Buddha, Dharma, and Sangha,’ the supreme Sangha refers to bodhisattvas. We can single them out in this way or just refer to the Sangha more generally as our companions on the path. As for how long we go for refuge, it is for lifetime after lifetime.”

“We can say the refuge prayer three times or just once, depending on how much time we have and our inclination. We take refuge with great certainty, calling forth one hundred percent of our being. If we can do this, Chenrezik will look after and care for us, so we can rest at ease, feeling stable trust in him. Briefly, this section has described the way we should think about going for refuge, which is expressed in the first two lines of the verse and relies mainly on the visualization of Chenrezik in front of us.

“The last two lines relate to the awakening of bodhichitta, and the focus is on both Chenrezik and all the living beings surrounding us, everyone of whom has been our father or mother. This statement implies past and future lives, which may be difficult for some to accept, so we could also recall that all the living beings around us are similar to us in their wish to be happy and avoid suffering.”

But people are not creating the causes for this to happen. On the contrary, the Karmapa remarked, “they are accumulating the causes that result in misery, so they will not find supreme, unchanging happiness, which is needed to attain buddhahood.

“Just having the thought, ‘Wouldn’t it be wonderful if living beings attained supreme happiness?’ is not enough, because at this point in our practice, we are not able to bring this about. Therefore, we study about Chenrezik and engage in the practice to develop our love and compassion. We make a wholehearted commitment to visualizing him and reciting his mantra, so that we will become like Chenrezik embodying universal love and compassion for the benefit of all living beings. Having generated bodhichitta, we dedicate all our practice of meditation and mantra recitation so that we may attain the level of buddhahood for the benefit of all. We repeat this generation of bodhichitta as often as time permits.

“After taking refuge and awakening bodhichitta, we imagine the following. From the body of Chenrezik present in front of us radiates an abundance of beautiful light rays, which purify all living beings of every negative action, suffering, and discomfort, and bring them happiness. The purpose of this thought is to fill our minds with delight. It does not necessarily mean that our goal will be accomplished right away, but it does bring benefits. We tend to think depressing thoughts when we are feeling down and happy thoughts when we are feeling upbeat. The thought of bringing happiness to others brings us happiness and lifts us up as well.

“At the end of the practice, we imagine that Chenrezik dissolves into light and then into us. This purifies whatever is impure or not beneficial from our body, speech, and mind and endows us with greater power to benefit others.” With this, His Holiness concluded a brief explanation of refuge and awakening bodhichitta.

Session Two

Beanfield Centre, Toronto, Canada on October 27, 2018

The Background of the Practice

This afternoon, His Holiness continued his explanation of “the All-Pervading Benefit for Beings,” a practice of noble Chenrezik, who is the embodiment, or the expression of the compassion of all the buddhas in the form of a yidam deity. For the inhabitants of the six realms, his great compassion is swift. In particular, since the Land of Snows is the area of his activity, he has become the special deity of the Tibetans, who have a karmic connection with him. Further, Chenrezik has made aspiration prayers to help those who have committed negative actions. For all these reasons, it is important to supplicate him.

“In general, the four classes of tantra contain different sadhanas of Chenrezik, and here we are looking specifically at the one made famous by the siddha Thangtong Gyalpo. It is said that he did not compose it on his own initiation. He had a history of meeting, as if in person, buddhas and bodhisattvas, such as Chenrezik, Hayagriva, Tara, and others. Thangtong Gyalpo often had visions of Chenrezik, who once told him, ‘I’m your spiritual friend. You should create a vast benefit for all living beings through teaching my six-syllable mantra and bringing all wanders in samsara to liberation.’ At this urging, Thangtong Gyalpo wrote ‘the All-Pervading Benefit of Beings,’ which has a vibrant power that brings actual blessings and a deep meaning to all who make a connection with it. They will be cared for by Chenrezik, so it is important to realize this.”

Meditating on the Deity

During the morning session, the discussion of refuge and awakening bodhichitta has been completed, and now the Karmapa turned to an explanation of how to meditate on the deity. This section of the text begins, “On the crown of myself and others” and ends twelve lines later with “He is the embodiment of all objects of refuge.”

His Holiness explained, “We remain in our usual form as ordinary people, so this is not a self-visualization as the deity. Similar to taking refuge, we are surrounded by all living beings, friends and enemies alike. First, we bring all of this clearly to mind and then we imagine that above our crown and those of all living beings is an eight-petaled, white lotus with its round corona in the center. On top of this is the mandala of a full-moon disk, and at its midpoint is the letter HRIH, luminous with its lights of pearl-white and emblematic of all buddhas’ compassion. It is as if universal compassion has manifested as a letter.

“The clear white HRIH radiates innumerable rays of moonlight that travel out to pervade all the realms in the ten directions; they imbue with light all the buddhas and bodhisattvas residing in these realms. Imagine that at the tips of the rays are innumerable offerings extended to all of them. The rays of light also reach out to all ordinary living beings, and as the lights connect with them, they are liberated from all disease, discomfort, negative forces, and so forth. Likewise, all their abodes in the six realms are purified and transformed into the realm of Amitabha or into pure lands filled with bliss and delight.

“These lights carrying all the blessings of the buddhas and bodhisattvas are drawn back into ourselves and dissolve in the letter HRIH. It becomes so filled with this light and charged with power that it breaks open, transforming into noble Chenrezik. White in color, he has four arms and radiates everywhere clear white light reflecting the five colors.

“His smile is filled with love for us and all living beings. Of his four arms, the hands of the first two are joined in prayer, the lower right hand holds a crystal mala, and the lower left hand, a long-stemmed white lotus with eight petals. On his upper body, he wears a garment of white silk and on his lower body, silk skirts. He is adorned with the eight types of ornaments, the jeweled crown, necklaces, and so forth. His left shoulder is covered by the skin of a trinasara (a kind of antelope), and on the crown of his head is his Lord of the Family, the Buddha Amitabha in a nirmanakaya form and red in color. His hands rest in the mudra of equipoise and his legs are crossed in the vajra posture. A luminous white moon disk free of stains serves as his backrest. Imagine that Chenrezik is the very essence of all the buddhas and bodhisattvas of the ten directions. This is the description of the yidam deity for the meditation.”

The Karmapa then read the visualization from the text:

On the crown of my head and those of all beings pervading space

Is a white lotus and moon, on which appears the syllable HRIH.

It turns into noble and supreme Chenrezik,

Radiating white light that shines in five colors.

Handsome and smiling, his gaze is filled with compassion.

Of his four hands, the first two are joined in prayer

While the lower two hold a crystal mala and white lotus.

Adorned with all the silks and jewels,

He wears an upper robe of antelope skin

While Amitabha resides as his crown ornament.

Chenrezik’s his legs are crossed in the vajra posture

And his backrest is a full moon, free of stains.

He is the essential nature of all objects of refuge.

The Karmapa continued, “As you slowly chant these words, reflect clearly on the meaning of each one. As I had mentioned this morning, depending on their physical condition, some people can more easily create the visualizations and others find it difficult. Of course, it is important to work with the form of the deity; however, I wonder if it is that important to see them exactly as in the paintings or statues. What is important is to imagine a white lotus on our crowns and on those of all living beings. A white lotus is something we all have actually seen, so it is easy to imagine, whereas Chenrezik with four arms is not what we normally see.

“You might task, ‘What’s the point of imagining a white lotus?’ ‘How could this possibly benefit my mind?’ In the mantrayana, we speak of what illustrates and what is illustrated or the symbol and its referent. These two make connections between our outer and inner worlds, establishing mutual relationships. It is not the shape of the image that is central but its inner meaning. If we can work with our minds in the right way, then over time, the symbolic form will naturally appear imbued with its meaning. Focusing our attention on the form does not help; we should reflect deeply on its significance.

“It is essential to understand what a symbol represents. The roots and stalk of a white lotus live in a muddy pond or swamp, but the white flower itself rises above the surface as something delightful and beautiful to see. Therefore, here in the practice of Chenrezik, the white lotus signifies the mind filled with renunciation (the purity of the white lotus) or the wish to be free of samsara (the muddy water). We meditate on a white lotus and simultaneously on its meaning.

“Above the white lotus is the mandala or disk of the full moon, the seat of Chenrezik. Here, again, we might ask, ‘Why meditate on a moon disk?’ Because it symbolizes relative bodhichitta. All beings are capable of love, for example, for their parents or for their children but this kind of love is biased or one-sided since we feel it only for those who are close to us and not for others. The moon, however, is full and round, open on all sides. It symbolizes relative bodhichitta, which encompasses all living beings with the wish to bring everyone to full awakening. By meditating on this meaning, the image acquires an emotional coloring, something we can feel, and then slowly, if we reflect well, the form will appear with its meaning clear to us.

“The next step is to move beyond our particular situation and see that residing above the crowns of all living beings is noble Chenrezik, the essence of love and the embodiment of great blessings. Through feeling this, our concepts and afflictions naturally subside, because our intellect is engaged in a vast visualization that leaves no room for concepts to arise. For this reason, it is critical to imagine that Chenrezik—the union of the love and power of all buddhas and bodhisattvas—is present everywhere.

“To recap, our mind is trained on the visualization and that focus closes out the constant stream of concepts and afflictions that move through our mind. We also move along the way to becoming like Chenrezik since this practice increases the power of our love. Meditating on a deity is not recalling or fabricating a drawing, painting, or sculpted image. It is not just a thought in our mind. Rather, the visualization feels vivid, alive, truly present, and full of power. Relative bodhichitta is likened to a moon because moonlight has the power to shine all over the earth. Likewise, relative bodhichitta is dynamic and strong like a powerful tool placed in our hands that we could use to benefit others. For all these reasons, we practice meditating on the deity.

Reciting the Mantra

Part One of Two Parts: Supplicating and Invoking the Mind of Chenrezik

“The next section of the practice is Reciting the Mantra and this has two parts: Supplicating and Invoking the Mind of Chenrezik, and the Practice of Realizing the Deity’s Body, Speech, and Mind through Radiating Light and Drawing It Back In.”

The Karmapa read the supplication:

Lord, white in color, untouched by faults,

A perfect Buddha adorns your head.

Looking upon beings with eyes of compassion,

To you, Chenrezik, we prostrate.

“We have been imagining Chenrezik above our heads and those of all living beings, and now we think of him as also present in the space in front of us—we are supplicating him and he is looking at us with compassion. Together with all the living beings who surround us, we recite the supplication as one voice, dedicating ourselves 100% to our resolution of freeing all living beings of the six realms of samsara. We pray to Chenrezik that he will bring them all to his level of omniscience. This supplication can be recited 7, 21 or 100 times or, until this feeling arises in our minds, which is the best way.

“As a supplement to this section, we can recite other praises of Chenrezik that are imbued with blessings; for example, the praise in the White Lotus Sutra, ‘the Praise of Noble Chenrezik’ by Gelongma Palmo, or ‘the Lamentation Requesting Blessings from Chenrezik’ by Chandrakirti. The main point here is that we discover and feel confidence and trust in Chenrezik as we think, ‘You are the one who knows.’ ‘Through this and all my many lives, I trust in you completely.’ It does not make any difference which praise you recite as long as it is one that you know and one that moves you deeply. This ends this section, Supplicating and Invoking the Mind of Chenrezik.

Reciting the Mantra Part Two: The Practice of Realizing the Deity’s Body, Speech, and Mind through Sending Out and Drawing Light Back In.

“Through our supplicating Chenrezik one-pointedly, we have invoked his mind, and from his body above our crown, infinite white lights hued in five colors radiate and permeate us and all living beings. This clears away the thick darkness of ignorance, present for infinite eons and never before illuminated. Also purified are the actions of immeasurable consequences, the ten misdeeds and similar actions of body, speech, and mind as well as the vows and commitments that we have transgressed. We feel that we have received all the blessings of Chenrezik’s body, speech, and mind.

“By meditating in this way, we have become inseparable from Chenrezik and our body is transformed into his. Likewise, the beings of the six realms surrounding us are permeated by his blessing and they, too, turn into Chenrezik, so that all living beings take his form. The place where they reside, the container of the external world, is also transformed into a pure land or Dewachen, the pure land of Amitabha. Further, the speech that is orchestrated by our mind and the sounds that are not (such as those of the natural elements) become the six-syllable mantra, the very essence of Chenrezik’s speech. Finally, everything that comes to mind, all memories and concepts, turn into awareness and emptiness inseparable, the very essence of Chenrezik’s mind. In brief, we imagine that all appearance, sound, and thought are transformed into the great bliss that is the deity; we have become the very nature of Chenrezik’s body, speech, and mind.

“Transforming ourselves into the essence of Chenrezik has specific purposes. The heart of the matter is that we are thinking of ourselves as Chenrezik. Since we are imagining ourselves as the embodiment of all the buddhas’ compassion, it does not quite feel right to get angry or jealous. Further, the usual way of seeing our appearance and thinking of ourselves as an ordinary person are shifted by the thought that all phenomena are like an illusion and not truly existent. Thinking this way does require a certain comprehension of emptiness, because this mitigates against our strong attachment and continual grasping onto things. Emptiness allows phenomena to appear as illusions. It is also true that imagining ourselves as Chenrezik will enliven our enthusiasm and bolster our inner strength.”

The relevant part of the text for this practice is:

By supplicating one-pointedly in this way,

Rays of light stream forth from the body of the Noble One

Purifying tainted karmic appearance and confused consciousness.

The outer world becomes the pure land of Dewachen;

The body, speech, and mind of those dwelling within

Become the body, speech, and mind of Chenrezik—

Appearance, sound, and awareness are inseparable from emptiness.

The Karmapa continued, “After this comes the recitation of Chenrezik’s 6-syllable mantra Om Mani Padme Hung, which can be explained in many different ways. This is the main part of the practice, which we will look at tomorrow.

“Before closing this session, let us review what we have considered so far. First came the preliminaries of going for refuge and awakening bodhichitta, then the visualization of the deity, followed by reciting the mantra. Following this sequence will give us a feeling for the practice. Further, the sections of the practice build on one another. If the preliminaries do not go well, the visualization of the deity will not effective either. And if that is not successful, we will have trouble engaging in the recitation of the mantra. The earlier parts of the practice are a foundation for what comes later. If we can recognize this and increase our interest and involvement, the practice will go well.”

At the end of his talk, the Karmapa asked that the audience write down their questions they might have and give them to the organizers. Since not all of them could be answered, they will chose among them the ones that are not personal but relevant to many. The Karmapa said he would answer them the next day in the afternoon and hoped that this would be helpful to all the people who had come.

Session Three, The meaning of Om Mani Padme Hung

Beanfield Centre, Toronto, Canada on October 28, 2018

The Karmapa began this morning’s teaching by discussing Chenrezik’s six-syllable mantra, Om Mani Padme Hung, famous throughout Tibet. When children are about two years old and learning to speak, they learn this mantra, and so it can be found basically wherever Tibetans are living. The practice of Chenrezik’s mantra is also part of Tibet’s tradition of the secret mantrayana, which has preserved the profound oral instructions of the tantra related to Chenrezik.

The Karmapa continued, “As I had mentioned earlier, Tibet is considered the realm to be tamed by Chenrezik. Since this has been the case for centuries, it is not a question of whether a Tibetan has taken up the practice of Chenrezik or not; the very fact of being born Tibetan means that Chenrezik is one’s spiritual sovereign and guide. For a long arc of time, Tibetans have had a strong belief in Chenrezik.

“There is a close connection between the Karmapas and Chenrezik. The Fifth Karmapa, Deshin Shekpa (1384–1415) was invited to the court of the Ming Emperor Yongle (1360–1424). Knowing that the Karmapa was an emanation of Chenrezik, the emperor asked, ‘What is the best? Shall I recite supplications and praises to Karmapa or repeat a mantra based on his name?’ The answer was ‘Recite the six-syllable mantra.’ (The name mantra, ‘Karmapa khyenno’ came later.) At that time in China, the practice of the six-syllable mantra was not very widespread, and the interest in tantra was also limited. Due to the Karmapa’s visiting the emperor, many people began reciting the mantra and it became an important practice.

“From one perspective, the six-syllables are the name mantra of Chenrezik. From another, Chenrezik is a bodhisattva who embodies the great compassion of all the buddhas and incorporates their bodhichitta and activities as well as all of their power. This means that his mantra has the potency of what are known as truthful or powerful words. His strength and commitment to help others was inconceivable and so the benefits of his mantra, these words of truth, are wondrous.

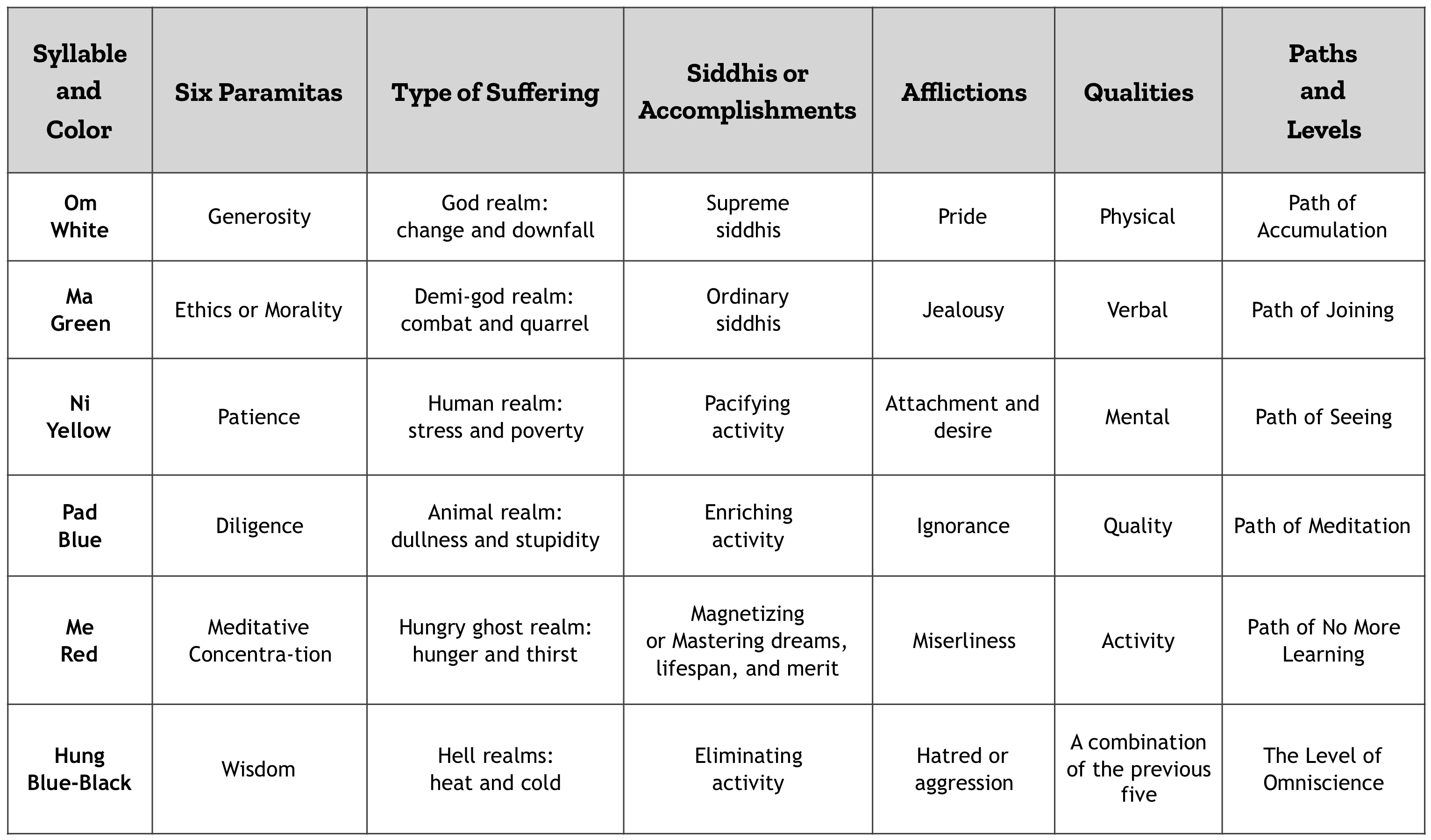

“One way of understanding the vast power of the mantra is to relate various sets of six qualities to the six syllables of the mantra. The first set is the Six Paramitas or Perfections. In their respective order, Om refers to the Perfection of Generosity; Ma to the Perfection of Ethics; Ni to the Perfection of Patience; Pad to the Perfection of Diligence; Me to the Perfection of Meditative Concentration; and Hung to the Perfection of Wisdom. The second set of six refers to the sufferings of the six realms that are eliminated through the power of the mantra. Om refers to the suffering of change and downfall in the god realm; Ma to the suffering of combat and quarrel in the demi-god realm; Ni to the suffering of stress and poverty in the human realm; Pad to the suffering of dullness and stupidity in the animal realm; Me to the suffering of hunger and thirst in the hungry ghost realm; and Hung to the suffering of heat and cold in the hell realms.

“The third set of six relates to the various kinds of siddhis or accomplishments. The first two are known as the ordinary and supreme siddhis or the mundane and transcendent siddhis. The last four of the six syllables are particular instances of the common siddhis, referring to the four types of action—pacifying, extending (or enriching), magnetizing (or mastering), and eliminating. Specifically, Om refers to the supreme siddhi; ma to the ordinary siddhis in general; Ni to the siddhi of pacifying sickness and negative spirits; Pad to the siddhi of extending life and merit; Me to the siddhi of magnetizing (dbang ’gyur) or mastering dreams, lifespan, and merit; and Hung to eliminating enemies and obstructers.

“The fourth set of six refers to the afflictions that are eliminated. Om purifies pride, Ma purifies jealousy, Ni purifies attachment, Pad purifies ignorance, Me purifies miserliness, and Hung purifies hatred. The fifth set of six refers to the benefits of various qualities. Om refers to the quality related to the body; Ma, the one related to speech; NI, the one related to the mind; Pad, the one related to qualities; Me, the one related to activity; and Hung represents the combination of them all. The sixth set of six is drawn from the context of the paths and levels. Om refers to the path of accumulation; Ma to the path of joining; Ni to the path of seeing; Pad to the path of meditation; Me to the path of no more learning; and Hung to the level of omniscience.

![]()

A syllable-by-syllable explanation of the mantra of Chenrezik, Om Mani Padme Hung.

A syllable-by-syllable explanation of the mantra of Chenrezik, Om Mani Padme Hung.![]()

“These sets of six lay out the numerous benefits that reciting Chenrezik’s mantra can bring. But merely saying, ‘These are the benefits’ will not make them happen. We need to learn how to do the practice. Of the six sets we just looked at, the most important here is the second one of purifying the six realms and clearing away their specific type of suffering.

“The practice is done in the following way. From the white Om, white light radiates and purifies the god realm, clearing away the suffering of change and downfall. From the green Ma, green light radiates and purifies the demi-god realm, clearing away the suffering of combat and quarrel. From the yellow Ni, yellow lights radiate and purify the human realm, clearing away the suffering of stress and poverty. From the blue Pad, blue lights radiate and purify the animal realm, clearing away the suffering of dullness and stupidity. From the red Me, red lights radiate and purify the hungry ghost realm, clearing away the suffering of hunger and thirst. Finally, from the blue-black Hung, blue-black lights radiate and purity the hell realms, clearing away the suffering of heat and cold.

“While we are reciting the mantra, we visualize ourselves as Chenrezik and clearly imagine in our heart the six syllables facing inward, set up in a circle like a wheel and turning clockwise. Alternatively, reciting the mantra and visualizing ourselves as Chenrezik, we bring to mind clearly an Om arising in our heart. It radiates brilliant white light that clears away the suffering of the gods. Then, for the remaining five syllables, we visualize in the same way but change the respective colors, realms, and sufferings.

“How many mantras should we recite? When on retreat, we can divide the day into four sessions (two in the morning and two in the evening) or into six sessions (three in the morning and three in the evening) and also decide on set a number of repetitions to do. If not on retreat, we can repeat as many mantras as time allows—the number is not predetermined. When we have finished the number of repetitions we set out to do, or if the time of a session has come to an end, we start the dissolution phase. From the body of Amitabha, the Lord of Chenrezik’s Family, red light radiates and transforms the world into the pure land of Dewachen and all beings into Chenrezik. This visualization then dissolves into light, or you could say it takes the form of light, and further dissolves into the Chenrezik, visualized in front of us, who dissolves into light and into us.

“Finally, we dissolve into light that has the nature of emptiness and clear light inseparable like luminous space. We reflect on emptiness and the sequence of visualizations that has brought us to the place where the meditator does not truly exist, the object of meditation, Chenrezik, does not truly exist, and the activity of meditating does not truly exist. Within this utter purity, freed of grasping onto subject, object, and action, we rest evenly in the dharmata (suchness).

This line of the text states:

Appearance, sound, awareness are inseparable from emptiness.

“While we are meditating like this, thoughts will come and go. They are the delusions of concepts or our relative truth. Our visualizations also arise from thinking; however, in the end, we must be able to return to what is present as the nature of the dharmata. If we are just moving from one thought to another, remaining stuck in the deluded world of our thinking, we will not be able to abandon our self-fixation. If we cannot do that, we will never come to the level of liberation. It is crucial to rest evenly in emptiness (or non-self) exactly as it truly is. Therefore, keep in mind that after dissolving the visualization, we should reflect for a few moments on no self or emptiness and then rest evenly in meditation. This is the key point.

“We have looked now at the benefits of reciting the six-syllable mantra, yet what determines whether we will realize them or not? A verse states:

The outer, inner, and secret conditions

Will remain successively in our minds.

The results will depend on

The aspirations we have made.

The treatises of scholars and the key instructions of past lamas speak of similar ideas: Our wishes, interests, and aspirations determine the result we find. The thoughts we have, the goals we set, and the plans we make will shape the outcomes we experience. Even if we are practicing for just one session, the attitude we have before starting it will color that time and its result.

“Often the Kadampa texts speak of the three types of individuals (lower, middling, and superior), based on what kind of intention they have. The lower type practices to be free of the sufferings in lower realms (hell, hungry ghost, and animal) and that is the extent of their benefit. The average type sees that samsara is nothing but suffering and practices to be free of it; this intention will set the limit of their result. Finally, the superior type practices to attain buddhahood or omniscience, and their result will harmonize with their intention.

“Clearly then, it is important to consider and set our intention before we start a practice, checking to see if it is pure or not. If it is not pure, we can revise it into a pure one that harmonizes with the Dharma. For example, if we are practicing in the mahayana, we look to see of our intention matches this path. It is the same if we are practicing the hinayana (foundational vehicle) or the vehicle of the mantrayana. We are always checking to see of our intention accords with our practice. If it does not, then the Dharma will not really be the Dharma. From the outside it may look like Dharma, but ultimately it is not true as Dharma.

“The results of our practice depend on our motivation and way of thinking. Especially, when we are reciting mantra, our mind should not stray elsewhere: Our awareness is fine-tuned and our attention is focused precisely on what we are practicing. If, however, we are saying the mantra while our mind is wandering, that discrepancy between what we are saying and thinking will keep our practice from becoming powerful. How we express ourselves physically and verbally is important; however, what really counts is remedying our minds, transforming ourselves from the inside. If we cannot do this, no matter how much we alter how we appear outside, we will have difficulties changing ourselves on a deep level.

“If we wish to change ourselves fundamentally, we need to look inward and see our basic motivation, attitudes, and character. With sincerity a Dharma practitioner should watch and correct their mind, continually checking: ‘Is it aligned with my intentions or not?’ ‘Is it correct or not?’ We should investigate like this while reciting the mantra. This completes the third section on reciting the mantra.

Subsequent Activity or Bringing Activity onto the Path

“We imagine that the mantra dissolves into emptiness, becoming inseparable from it, and we rest in that state. When we arise from it, infinite appearances emerge fresh and clear. These are pure appearances, different from the everyday phenomena of our surroundings that we usually encounter and take to be real and existent. The pure appearances are inseparable from emptiness, arising like the moon’s reflection in water.

Or one could say that pure appearances relate to the body, speech, and mind of Chenrezik: all forms are the form of Chenrezik; all sounds are the sound of the six-syllable mantra, and all memories and thoughts are the mind of Chenrezik, which is awareness and emptiness inseparable or bliss and emptiness inseparable. We should rest in our mind that does not move from this state. Whatever we are doing—going, staying, lying down, or moving about—we are not taking appearances to be ordinary, but see them as pure. This is known as the practice of pure appearance. This is described in the next lines of the practice:

The bodies of others and myself appear in the form of the Noble One,

Sounds are the melody of his six-syllable mantra,

Memory and thought are the immense expanse of primordial wisdom.

Since it might be a bit difficult to meditate on all forms as forms of Chenrezik, we could recall that just as we had imagined that our body like Chenrezik’s was emptiness and appearance inseparable, we could also imagine that all appearances are emptiness and appearance inseparable. Chenrezik’s body resembles the reflection of the moon in water—appearing while empty, and empty while appearing—and we can imagine that all appearances are like this.

It is the same for sound. It might seem a bit strange to meditate on all sound and speech as the six-syllable mantra, thinking that this is all that will reach our ears. Ultimately, however, the mantra is not something superior to ordinary sounds and speech. They all are the same—sounds appearing while empty, and empty while appearing. The essential nature of Chenrezik’s mantra is inseparable from all sound and we rest in meditation on this.

Likewise, we have various thoughts that come and go, yet no matter how numerous they might be, they are all thoughts appearing while empty and empty while appearing. They do not move beyond the expanse of having the same nature. If we can have this kind of awareness of emptiness, remaining alert and attentive to, or mindful of emptiness, we will be doing the practice well. The way we work with our mind is critical. It is not that we coerce ourselves to meditate that all we see has the physical form of Chenrezik or that all that we hear is the six syllables. It would be useful to study and reflect on these points. That concludes the fourth section

The Dedication of Virtue

The Dedication reads:

By this virtue may I swiftly

Become similar to the powerful Chenrezik

And place every living being, not one left out

On his noble level.

“This means, ‘May whatever virtue I have gathered through this practice as well as all the roots of virtue in my mindstream be dedicated for the benefit of all living beings, who all, in numbers vast as space, have been my mother. May they all swiftly attain the level of Chenrezik. May they all become similar to him.’ Essentially, we are praying for the ability to place all living beings on the level of Chenrezik. We could make other dedications similar to this as it does not make any difference which one we do. It is our intention that counts. This is the same with aspiration prayers.

“In our daily life, we might think, ‘Wouldn’t it be amazing to be like Chenrezik?’ and then make efforts to become someone on the mahayana path and turn into a bodhisattva. Though we might try hard to embody these ideals, we have deep-seated habits and a powerful ignorance that work against us, so we are continually defeated and victory is elusive. In the beginning of practicing Dharma, we want it to go well and we are happy to meditate. But gradually as time passes, we often become distracted, and so it is difficult to achieve our goal.

“At the start, we think it will be easy, but as we actually engage in meditation, it turns out to be more difficult than we had thought, so we worry. ‘It’s too difficult. I’m not up to this. It’s only for people with high realization and refined awareness.’ If we have such thoughts, we shouldn’t pay too much attention to them. No matter what work we may do, sometimes we will succeed and sometimes not. That is just the way things are.

“When we are practicing the Dharma, one of the most important things is that we have a deep-seated confidence in ourselves and our practice. No matter how often we might fail, the courage of our Dharma practice gives us the confidence to try again. We can be inspired, thinking ‘I’m going to succeed. I will make it happen.’ No matter how many problems we might have, we do not get discouraged, thinking ‘It’s just not working,’ but we simply continue to make an effort. Why? Not just this lifetime, but from beginningless time, we have been dealing with difficulties. When we remember this simple fact, having a rough time will not make us downhearted. We can motivate ourselves to keep going, knowing that like before, even if we have problems, we can eventually succeed.

“From another perspective, having difficulties is a sign that we are making an effort. If we were not trying to do something, there would be no problems. When they arise, it means that we are on the road to accomplishing some objective, so we need not feel despondent, but see these complications as part of a larger picture.

“In general, it is important to have a stable trust in our lama or spiritual friend, and we should also understand what this means. Many people place their trust in a teacher thinking that everything depends on that person. But if something happens that is a little bit out of line with their wishes, their trust in the lama immediately comes into question. Given this instability, we should look into the reasons why we placed our trust in the first place. We could be transferring the burden of responsibility for our lives onto the lama and then assuming that we have nothing to do. This will not work out. The reason we should be trusting our lama is that we are confident that they will give us oral instructions in harmony with the Dharma. Then we have to see if we can practice these instructions correctly or not.

“If we do apply them properly and the expected results do not come, then we might have a reason for saying that these instructions from the lama I trusted do not help. The problem is that many of us do not practice following the lama’s counsel, but do what accords with our own wishes. When this does not work, we blame the lama for our failure. This is not right. How is it then that we understand ‘having trust in the lama’? Whatever practice or project the lama gives us that accords with the Dharma, we carry it out as it was explained and blend it into the experience of our daily lives.

“In sum, before we can trust others, we need to trust in ourselves. Usually, however, we do not trust but carry a lot of doubt about ourselves. Without self-confidence, it is difficult to find trust in others. This is something we should reflect upon.

The Gyalwang Karmapa teaching the practice of Chenrezik and the mani mantra via live video stream.

“Since I have the name of the Karmapa, many people think, ‘He must not have any problems. He can do whatever he wishes and never suffers.’ Since the Karmapas have reincarnated for hundreds of years, they are considered very special and prestigious, worthy of veneration. But over time, this type of thinking morphs into seeing the Karmapa as so highly honored that he transcends the human condition.

“But if you take me for example, I am actually a regular human being, to whom a huge responsibility and an impressive name have been given, and that is what would differentiate me from others. Nevertheless, in people’s minds, this responsibility and importance are so spectacular that they pass beyond the human realm. It is difficult for me to perform the activity of someone who transcends this world.

“Every human being has faults and various kinds of suffering. I have experienced many of these and also many problems that others to not face and so people worry about me. Since I am at the center of many different situations, I know difficulties that almost no one else would know in their entire lifetime. In addition, most people have someone, their friends or parents, to whom they can talk about their problems, but I do not since no one else is dealing with a similar situation and it is difficult to really understand what I tell them. When difficulties arise that are as huge as Mt. Meru, I am expected to solve them like a superhuman being, but I do not have those qualities, so these situations are hard to work with.

“Nevertheless, no matter what expectations people might have of me as a human or superhuman, I try to do my best. If one day people would come to me and say, ‘You’re not the person in whom we placed our hopes. You’re just ordinary and you deceived us,’ it would not make a difference because though I’ve made mistakes, I have made a considerable effort to help others. I understand that no matter now hard I try, I cannot fulfill everyone’s expectations. For a long time, I have not practiced a lot of Dharma, but I have studied quite a lot so I think, ‘Let whatever problems there are come, I will not mind because I have the motivation to continually benefit others and to be loving and kind to them for all of my lifetimes. I will not stop doing this because there are obstacles or blocks in the road.

“The situation is similar for all of you. You might think that you are the only one who suffers so greatly but everyone knows suffering no matter what their stature might be. We all experience hardships and misery, and we all have faults. It could also be that we are not developing good qualities as quickly as we would wish. None of these, however, is any reason to become discouraged. We should continuously try to do our best. If we are defeated by one problem, we make twice the effort. If we are defeated ten times, we make twenty times the effort. If we continue in this way, one day we will be completely victorious and be able to benefit ourselves and others. Please keep this in mind.”

With this morning talk His Holiness finished teaching on the practice of Chenrezik. The session was followed by everyone engaging in the practice of Tara with the aspiration of benefiting his health and well-being.

General Comments on Visualization and Mantra Practice from the Question and Answer Session on October 27, 2018

How to practice the view of emptiness during the visualization of a deity or a mantra practice?

His Holiness explained, “In the Secret Mantrayana, when we are practicing visualization or mantra, it is important that the practice reverses our attachment to ordinary appearances. Whatever arises is mere appearance—emptiness and appearance inseparable—but due to our clinging to these appearances as real, the moment they arise, we immediately grasp them as truly existent and so we impair our ability to see their true nature. Things are not the way we think they are; we fixate on ordinary appearances and miss their actual nature because we do not comprehend emptiness.”

He continued, “Visualizing a deity or reciting a mantra stand in direct contradiction to our usual way of perceiving.” Before we do these practices, we must first reflect on the actual nature of things, on emptiness or the dharmata, and from within this true nature, arise the appearances of the deity, the support for our Dharma practice. With these, we think that we have created a new world, which arises out of emptiness and is inseparable from it.”

The next question asked about the practice of Chenrezik and radiating lights to all beings to eliminate their suffering, which in actuality seems impossible. Why do we do this?

The Karmapa replied, “The purpose is to train our minds. Our compassion is developed through the aspiration to eliminate all the suffering of living beings. Even if this does not actually happen, the thought, ‘Wouldn’t it be wonderful if it came true?’ gives us joy. Even if it is difficult to actually acomplish something or if they cannot, bodhisattvas still try to make it happen. Their aspirations are limitless, not restricted by ‘can’ or ‘cannot’; they work on what cannot be accomplished until it can be.

Video Teachings on the Chenrezik Practice

You can watch the video recording of this teaching on Chenrezik over at YouTube. Subscribing to the channel will ensure you receiving notifications of any new uploads.