The Philosophical basis of Mahayana Buddhism

1. Fundamental Philosophical Tenets Common to All Forms of Mahayana Buddhism

The advocates of Mahayana forms of Buddhism (the forerunners of which were the Mahasanghikas) accept all the philosophical tenets of Theravada Buddhism (as expressed in the Pali canon), but qualifies this acceptance by claiming to possess, in addition, a collection of the Buddha's more advanced teaching, which transcends or relativizes the teaching of what they refer to as the Lesser Vehicle (Hinayana, i.e., Theravada Buddhism). Thus, there are several significant philosophical advances that Mahayana Buddhism makes on Theravada Buddhism.

1.1. The Ideal of the Bodhisattva

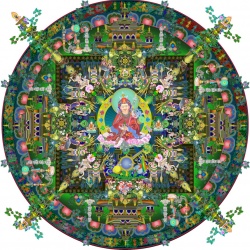

The religious ideal for human beings changed significantly during this period; in Theravada (or Hinayana) Buddhism the ideal is to become a monk (bhikku) and eventually through self-effort become an arhat, i.e., an enlightened one who would not be reborn, one who already has attained nirvana. This ideal is seen as self-centred by Mahayana Buddhism. To seek personal enlightenment and then to enter niravana upon death is seen as uncompassionate. The ideal set forth in Mahayana Buddhism is that of the bodhisattva (bodhi = enlightened; sattva = being), who is a human being who has attained enlightenment but deliberately has refrained from passing into nirvana at death, choosing rather to be reborn in order to enlighten others. The bodhisattva will not enter nirvana until all sentient beings are able to enter nirvana. Since in Buddhism the divisions between the realms are fluid, many of the boddhisattvas are seen as having been reborn in heaven and therefore become de facto gods to be venerated and petitioned. Bodhisattvas are all-compassionate beings who will help other sentient beings who call upon them in faith.

1.2. Emptiness (Sunyata)

1.2.1. Introduction

Unlike the Buddhism of the Pali canon, which is representative of Theravada Buddhism, Mahayana Buddhism concerned itself with metaphysical questions, foremost of which was the question of the nature of ultimate reality. In this later form of Buddhism, it is assumed to be impossible to separate metaphysics and the religious goal of release from samara. The ontological first principle of Mahayana Buddhism is emptiness (sunyata), which is also referred to as suchness (tathata), the body of essence (dharma-kaya) or even nirvana. (In the Mahayana sutras there are other synonymous terms used for the first ontological principle or the Absolute.) Everything in Mahayana Buddhism turns on its teaching about sunyata. The doctrine of emptiness states that ultimately all conceptual distinctions are non-existent or unreal, for everything is empty or devoid of "marks," or characteristics (lakana). In other words, everything is devoid of true individuality and own-being (svabhana) (sometimes translated as "self-nature"). All dharmas (individual things) are empty (sunya) and devoid of own-being because they are conditioned and impermanent. The assumption is that only that which is necessary and unchanging has own-being and for that reason can be said to exist in a real sense. All dharmas are without own-being (asvabhana), because nothing exists in a state of ontological permanence and independence.

1.2.2. Dharmas as Empty

The Buddha's teaching of the Chain of Causation or Dependent Origination is the presupposition of the Mahayana concept of emptiness (sunyata). In the Pali canon, the Chain of Causation or Dependent Origination is applied in particular to the human beings to explain how they are what they are in the present and how they can escape from samsara in the future; the goal of this sort of anthropological analysis is to provide insight into the ultimate empty nature of any conception of the self, which is the presupposition of the cessation of craving. What is applied primarily to the individual in the Pali canon, however, is applied to all dharmas in the Mahayana sutras. Whatever dharmas that exist in the phenomenal world (or samsara) are what they are only by virtue of being conditioned by (or dependent on) other dharmas. (By dharma is meant any entity that is wrongly assumed to have individual, separate existence, including immaterial entities as thoughts and abstract concepts.) They have come into being as conditioned (or caused) and will in turn condition other things to come into being. This is said to be the more profound truth of the Buddha's teaching about the Chain of Causation or Dependent Origination. All dharmas are conditioned diachronically in the sense that a dharma depends upon other dharmas in the past for its production. A wooden table, for example, depends for its existence upon a tree, which depends for its existence on the rain, which depends for its existence on clouds, which depends for their existence on the sun. (Of course, the wooden table also depends for its existence on the carpenter and the logger.) But dharmas are also conditioned synchronically in the sense that the parts of a system are co-dependent. A body as a system, for example, is composed a various organs that depend on one another. The heart pumps blood to the kidneys thereby providing them with oxygen and nutrients but the same kidneys purify the blood enabling it to bring oxygen and food to the other organs. What is conditioned is understood as empty (sunya), that is, empty of own-being. In the Avatamsaka (Flower Garland) Sutra, the conditioned nature of all dharmas is compared to the Jewelled Net of Indra, which is a net extending in all directions infinitely. (Indra, the Vedic high god, has a net hanging over his palace on Mt. Meru, the mythical center of the world and dwelling place of the gods.) The net has a multifaceted jewel at each vertex that is reflected in all the other jewels; in addition the reflections are also reflected in each jewel. This reflectivity gives the collection of jewels its brilliance. The point is that all the jewels are co-dependent for their quality of brilliance, just as all dharmas are co-dependent on all other dharmas for their existence and identities. Only that which is unconditioned can be said to have own-being and to exist truly.

In addition to being conditioned, dharmas are also impermanent; in fact, this is a necessary correlative of their nature as conditioned. Dharmas both come into being as conditioned or in dependence on other dharmas and also cease to exist as conditioned by other dharmas. In fact, in some cases, new dharmas cannot come into existence unless other dharmas cease to exist. (A flower, for example, ceases to exist in the process of becoming a fruit.) Only that which is permanent can be considered to have own-being and so truly exist.

In conclusion, all dharmas are characterized as both conditioned and impermanent. This is what it means to be empty of own-being. If something were not empty it would be unconditioned and permanent but there is nothing in this phenomenal world (samsara) that meets the criteria of being non-empty. It should be noted that the assertion of the emptiness of all things is not to deny the limited reality of the phenomenal world, i.e., the world of plurality and change, but only to deny that it has own-being, by which is meant true existence. This means that everything is contingent and transitory as opposed to necessary and permanent. The things in the phenomenal world arise through causes and conditions and in turn cause and condition other things to arise. This view of phenomena as existing between the absolutes of existence and non-existence is another application of the middle way of the Buddha.

The teaching about the three marks of existence likewise suggests the Mahayana concept of sunyata: impermanence, suffering (dukkha) and not-self (anatman or anatta). Not-self is the functional equivalent of not having own-being. If everything that can be identified as something is impermanent, then it follows that the only permanence is that which is devoid of all marks or distinctiveness, which is no thing or sunyata. In other words, what is real is that which is not identified as anything or as empty; only that which is devoid of all marks or characteristics is permanent and ontologically independent (but even these terms do not apply to it, and one cannot even call it an it).

1.2.3. Emptiness as the Absolute

In Mahayana Buddhism there is a subtle back and forth movement between speaking of the emptiness of all dharmas and speaking about emptiness as the Absolute, which is the unconditioned and permanent, the opposite of all dharmas. The statement that all dharmas are emptiness becomes emptiness is all dharmas. In other words, the Mahayanist is not simply claiming that all dharmas lack ultimate existence because of their conditioned and impermanent nature but also that emptiness itself, which characterizes all dharmas, is the Absolute. Without an appreciation of this continuous back and forth movement, the Mahayana teaching on emptiness (sunyata) is missed. (To give unity to this presentation, what Mahayana Buddhism describes variously shall be called the Absolute. The term the Absolute is from the Latin absolutus, meaning freed from or complete; as applied to ultimate reality the meaning is ontologically independent and unconditioned.) Since all dharmas are non-different insofar as they all are empty (sunya) it follows that they are all the same (sama) by virtue of being empty. In other words, they are all manifestations of the same emptiness, the unconditioned and permanent source of all conditioned and impermanent dharmas. No dharma has any claim to ultimate reality, because every dharma is conditioned and impermanent; only that which is the negation of all dharmas is ultimately real, and this is called emptiness, which all dharmas share and which they ultimately are. The unstated assumption is that the conditioned and impermanent requires a cause that is unconditioned and permanent. This cause cannot have any marks or essential characteristics (including the mark of being a cause!) since it would then be a dharma, an individual thing as distinguished from other individual things, and would so be conditioned and impermanent. That which supports dharmas is emptiness; it is empty because nothing can be affirmed or denied of it. In other words, emptiness is no dharma but the "cause" of all dharmas. Or, expressed differently, all dharmas are it as differentiated. (In the Pali Canon, nirvana is described as "not-born, not-brought-to-being, not-made, not-conditioned," which explains why nirvana is sometimes used in Mahayana Buddhism as a synonym for emptiness [[[Udana]] VIII. 3].)

Naturally, emptiness (sunyata) is beyond comprehension and impervious to discursive thought, since to understand and speak is to make distinctions. Even to call it emptiness is to speak falsely, because emptiness is a mark or characteristic. In Mahayana sutras, reference is sometimes made to the emptiness of emptiness, which means that emptiness is not to be considered as a dharma, or intellectual entity, something to be believed and to which to be attached. It follows that no philosophical statement, however profound, is true or false, not even statements about sunyata; thus even the basic tenets or beliefs of Buddhism are empty, without own-existence. Attachment to Buddhist teaching (dharmas) is seen as an indication of inferior understanding. When he or she turns the Buddhist teaching about sunyata into a belief to be grasped and rejects the opposite teaching as false, a person has misunderstood the teaching about sunyata. Any statements about emptiness are always to be understood as empty, as failing to point to the Absolute. It must also be stressed that an awareness of emptiness (sunyata) is intuitive and is only achieved through meditation (yoga); one does not come to know emptiness by accepting certain propositions about it. This is not enlightenment.

It is important to point out that in the teaching of emptiness (sunyata) negations are equally empty as affirmations. (One cannot even say that sunyata is absolute negation, because this is to give it a mark or characteristic. Because he or she has not affirmed anything, it does not follow that the one who has true wisdom denies that anything is true; rather such a person neither denies nor affirms anything. One must be on guard not to make the negation of all affirmations into the functional equivalent of an affirmation. According to Mahayana Buddhism, there is no dharma but also there is no no-dharma. To deny is to negate the pairing of a subject and a predicate, to say that a subject is not a particular predicate; it is the opposite of affirmation, but still shares the same nature as affirmation: to distinguish one idea from others as true or false. Denial still presupposes, in other words, the making of distinctions, the impossibility of which is the defining insight of the truly wise or enlightened. It should also be noted that logically to deny presupposes that the opposite of what is denied is true, but this would be affirmation, which is impossible given the emptiness or ultimate unreality of all distinctions. When there are no real ontological distinctions one can neither affirm nor deny. Neither to affirm nor deny is the closest that one can come by means of discursive thinking to emptiness (sunyata). Besides, to attribute being or non-being to that which is impermanent is inappropriate, since such categories can only apply to permanence; the impermanent neither is nor is not. In fact, however, the categories of existence and non-existence do not apply to sunyata. Not even the teaching about emptiness should be taken as an affirmation of negation, to be held on to as a (conceptual) dharma. Thus the doctrine of sunyata is the middle way between affirmation and denial.

In the Mahayana sutras, emptiness (sunyata) as the Absolute goes by many other names, which of course are not really names, since names signify dharmas. Of special importance is the term suchness (tathata), so used to denote a dharma such as it really is. Suchness is the most abstract term possible to designate dharmas; it becomes thereby a designation for the Absolute. The fact that all dharmas are the same insofar as they all are empty means that they are all "suchness" (tathata). Behind the facade of separateness and individuality, dharmas are all the same; when considered apart from their differences from one another all dharmas have suchness in common. (The Western equivalent of the term suchness would be "being" [esse]: all things have being in common.) To view the suchness of dharmas is to strip away all of its individual distinctives and see it in its more abstract nature. Since they are suchness, all dharmas are all manifestations of the same Absolute, which gives them their suchness. So suchness becomes another way to denote that which gives dharmas their own suchness, which is to say the Absolute. It must be noted that, although they are not different from it, dharmas are also not simply identical to suchness. This is another expression of the middle way between affirmation and denial: dharmas neither exist in an ultimate sense nor are they non-existent. Thus they have a non-ultimate existence.

Is it possible to interpret emptiness (sunyata) (or suchness) as God understood non-anthropically?

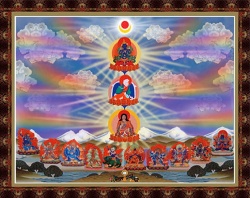

1.3. The Three Bodies of the Buddha

In Theravada Buddhism the Buddha was a human being who had reached enlightenment and sought to enlighten others, his followers. In Mahayana Buddhism, the Buddha is said to have three bodies (trikaya), by which is meant three aspects or natures. The first body is the body of essence (dharma-kaya); the Buddha's body of essence is that ultimate reality underlying all other reality. (This is essentially equivalent to Brahman in the Upanishads and any other expression of the Absolute, including sunyata and Tathata.) The second body is the body of bliss (sambhoga-kaya), which is the mode of the Buddha's existence in non-earthly realms. Emanating from and dependent on the body of essence, the body of bliss is the Buddha's existence as a supreme, god-like being. There is a multiplicity of bodies of bliss occupying different non-earthly realms, which gives rise to the view that there are many Buddhas, each of which has the same body of essence, and many Buddha-lands, or cosmic realms. As a supreme god the Buddha can be an object of worship or veneration. The third body is the transformation body (nirmana-kaya); this was the Buddha as the body of bliss appearing on earth as the historical Siddhartha Gautama. Of course, the Buddha has appeared at other periods in the past and will appear again in the future; one specific future manifestation of the body of bliss is to be Maitreya, who is almost a messianic figure. The differentiated of the three bodies of the Buddha allows the possibility of speaking of the Buddha as the Absolute, as a transcendent being and as a historical figure..

1.4. Skill in Means

Arising from the doctrine of sunyata is the idea of "skill in means" (upaya kausala). This describes the Buddha's pedagogical technique of tailoring his teaching to the level of his audience. Even though ultimately there is emptiness (sunyata), few can grasp this, so that the Buddha's teaching must assume that there are such things as the Buddha, bodhisattvas, nirvana and dharmas and so forth. Only when the people have progressed to the appropriate level will the Buddha reveal that ultimately there is nothing, not even "true" Buddhist teaching. The Theravada teaching is often explained as the Buddha's lower teaching, which should give way to the higher teaching of the Mahayana doctrine of emptiness.

Is the doctrine of the three bodies of the Buddha a reversion to polytheism? Is the Buddha's skill in means pedagogical dishonesty?

2. Selected Mahayana Sutras

There are innumerable Mahayana Buddhist sutras in existence and most of these have not been translated into European languages. There are a few important Mahayana texts that have been influential in the dissemination of Buddhist teaching.

2.1. Prajnaparamita Texts

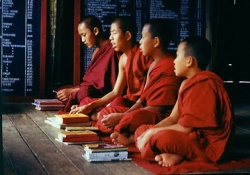

There are several Prajnaparamita (Perfection of Wisdom) Sutras of differing lengths. There is a longer Prajnaparamita Sutra, and a shorter version consisting of 8,000 stanzas (slokas) known as Astasahasrika, which is probably the earlier version, c. 100 BCE. In this Mahayana text, wisdom (prajna) is an insight into the emptiness of all dharmas, which means the rejection of the own-being (svabhana) of all dharmas. Moreover, this emptiness is the Absolute. There are also many short Prajnaparamita Sutras versions, the two most important of which are the Heart Sutra (Hridaya Sutra) and the Diamond Sutra (Vajracchedika Sutra). (The Heart Sutra is frequently recited by Buddhist monks.) The Prajnaparamita texts do not contain philosophical arguments so much as intuitional assertions (or more accurately non-assertions). They are born of meditational experience, and are full of paradoxical statements. There tends to be much repetition in the larger Prajnaparamita sutras, no doubt the result of a long process of literary growth.

2.1.1. The Heart Sutra

When avalokitesvara bodhisattva is practising the profound Prajna-paramita, he sees and illuminates to the emptiness of the five skandhas, and this attains deliverance from all suffering. Sariputra, form/matter is not different from emptiness, and emptiness is not different from form/matter. Form/matter is emptiness and emptiness is form/matter. So too are feeling, perception, mental fabrications and consciousness.

The one known as avalokitesvara bodhisattva (a particular bodhisattva) practices prajna-paramita or perfect wisdom, with the result that he understands the emptiness or ultimate unreality of the five skandhas. This means that, not only is the human being composed of the five skandhas empty of self-existence, but the skandhas themselves equally are empty of own-being. This precludes the adoption of the position that the basic elements of human existence are real in the sense of being permanent and independently existing, even if the products of their coalescing, i.e., human beings, are not. To say that emptiness is not different from the five skandhas nor the five skandhas different from emptiness is to affirm the non-dualistic nature of reality. There are not the five skandhas and emptiness as the Absolute, as if the two were two different things. One could say that the five skandhas have emptiness as their true nature in the sense that all things are one thing, emptiness as the Absolute. Emptiness does not exist apart from dharmas or phenomena but is identical with them in the sense that, to use a metaphor, it permeates them. The assertion that "Form/matter is emptiness and emptiness is form/matter" is an example of the subtle movement from emptiness as denoting the ontological state of being conditioned and impermanent to emptiness as denoting the Absolute.

Sariputra, all dharmas are marked with emptiness. They do not appear or disappear, are not tainted or pure, do not increase or decrease. Therefore, in emptiness no form/matter, no feelings, perceptions, impulses, consciousness. No eyes, no ears, no nose, no tongue, no body, no mind, no color, no sound, no smell, no taste, no touch, no object of mind, no realm of eyes, and so forth until no realm of mind consciousness. No ignorance and also no extinction of it, and so forth until no old age and death and also no extinction of them. No suffering, no origination, no stopping, no path, no cognition, also no attainment with nothing to attain.

It is said that all dharmas are characterized by emptiness. In other Mahayana texts, dharmas means entities or things assumed to exist, not simply material things but ideas or abstract concepts also. In the Heart Sutra, however, dharmas probably refers more specifically to the fundamental or simple units of reality, from which complex entities are composed, the "atoms" of existence. The point is that nothing can be said to have own-being, not even the basic elements of existence; the assumption is that there are no actually unconditioned and permanent elements of existence, contrary to the views of the Hinayanist (the term Mahayanist give to Theravada Buddhists). Rather, all dharmas have the mark of emptiness, which means that even the basic elements of existence are conditioned and impermanent. This is why the Heart Sutra goes on to affirm that dharmas "do not appear or disappear, are not tainted or pure, do not increase or decrease." Only that which has own-being can receive attributes and therefore be the true subject of propositions. Dharmas, however, as already indicated, lack own-being, and so nothing can be affirmed nor denied about them. All phenomena are ultimately ontologically derivative of emptiness, which is the Absolute. It follows that the elements of Buddhist anthropological analysis (the five skandhas and the six twelve sense fields composed the six senses and their objects) do not truly exist in the sense of having own-being, so that the concepts of fundamental Buddhist teaching are ultimately unreal. Furthermore, if all dharmas are empty, meaning that no conceptually-distinct thing exists, then there can be no reaching of the religious goal, for there is no ignorance nor liberation from it. In fact, there is no one to be liberated. In other words, there is no suffering and no cessation of suffering; in short, there is nothing to obtain.

Because there is nothing obtainable, bodhisattvas through the reliance on prajna-paramita have no attachment and hindrance in their minds. Because there is no more attachment and hindrance, there is no more fear, and far away from erroneous views and wishful thinking; ultimately: the final nirvana. Buddhas of the past, present, and future all rely on prajna-paramita to attain annutara-samyak-sambodhi (Consummation of Incomparable Enlightenment).

Therefore, realize that prajna-paramita is the great wondrous mantra, the great radiant mantra, the unsurpassed mantra, and the unequalled mantra. It can eradicate all suffering, and it is genuine and not false. Therefore, utter the prajna-paramita mantra—Chant: Gate Gate Paragate Paramsagate Bodhisvaha (gone gone totally gone totally completely gone enlightened so be it).

Only when there is nothing to obtain can there be truly no attachments. The one who believes in the reality of suffering and nirvana becomes attached to the religious goal of the elimination of suffering and obtaining nirvana; in a sense one can become just as attached to this religious goal as one can be attached to the illusory sense of Self supposed to exist as the possessor of the five skandhas. Any attachment, even "religious" attachments are hindrances to the mind and for that reason prevent enlightenment. The realization of the emptiness of all dharmas, including central and cherished Buddhist beliefs, leads to no fear of not obtaining the goal and being reborn into samsara; fear vanishes when one realizes that there is no obejct to be feared and no subject to perform the fearing. To be in this state of understanding is nirvana. This realization of the emptiness is annutara-samyak-sambodhi (unexcelled, ultimate and perfect insight). The chant "Gone gone totally gone totally completely gone enlightened so be it" describes the enlighteed one who has gone beyond views and who sees all things as empty of own-being.

2.1.2. The Diamond Sutra (Chapters 1-10)

A. Chapter One

The Convocation of the Assembly

Thus have I heard. Upon a time Buddha sojourned in Anathapindika's Park by Shravasti with a great company of bhikhus, even twelve hundred and fifty. One day, at the time for breaking fast, the World-honored One enrobed, and carrying His bowl made His way into the great city of Shravasti to beg for His food. In the midst of the city He begged from door to door according to rule. This done, He returned to his retreat and took his meal. When he had finished he put away his robe and begging bowl, washed his feet, arranged his seat, and sat down.

The following discourse is said to have been delivered by the Buddha in the Jeta Grove to a group of bhikhus, i.e., disciples. The description of the Buddha's actions are typical of Buddhist monks..

B . Chapter Two

Subhuti Makes a Request

Now in the midst of the assembly was the Venerable Subhuti. Forthwith he arose, uncovered his right shoulder, knelt upon his right knee, and, respectfully raising his hands with palms joined, addressed Buddha thus: World-honored One, if good men and good women seek the Consummation of Incomparable Enlightenment, by what criteria should they abide and how should they control their thoughts? Buddha said: Very good, Subhuti! Just as you say, the Tathagata is ever-mindful of all the Bodhisattvas, protecting and instructing them well. Now listen and take my words to heart: I will declare to you by what criteria good men and good women seeking the Consummation of Incomparable Enlightenment should abide, and how they should control their thoughts. Said Subhuti: Pray, do, World-honored One. With joyful anticipation we long to hear.

Subhuti asks the Buddha to explain how someone who has decided to pursue supreme wisdom (Consummation of Incomparable Enlightenment) should dwell and subdue the heart. How to dwell means something like how to remain in a proper state of being; to subdue the heart means how to eliminate influences that would prevent proper dwelling. The Buddha agrees to answer these questions.

C . Chapter Three

The Real Teaching of the Great Way

Buddha said: Subhuti, all the Bodhisattva-Heroes should discipline their thoughts as follows: All living creatures of whatever class, born from eggs, from wombs, from moisture, or by transformation whether with form or without form, whether in a state of thinking or exempt from thought-necessity, or wholly beyond all thought realms—all these are caused by me to attain Unbounded Liberation Nirvana. Yet when vast, uncountable, immeasurable numbers of beings have thus been taken across to extinction, verily no being has been taken across to extinction. Why is this, Subhuti? It is because no Bodhisattva who is a real Bodhisattva has a mark of self, a mark of others, a mark of living beings, or a mark of a life.

The Buddha explains that all bodhisattvas should subdue the heart by taking a vow to selfless service to all beings in order to bring them nirvana without residue, i.e., nirvana with no residue of karmic effects; this is synonymous with being taken across to extinction. This eliminates all selfish impulses.

The Buddha also says paradoxically that there is actually no being liberated or taken across to extinction. The meaning is that ultimately no individual thing exists, so that no being crosses over to extinction. He adds that a bodhisattva is no true bodhisattva if he "has a mark of self, a mark of others, a mark of living beings, or a mark of a life." The meaning is that if he has a belief in the independent and permanent existence of individual things (things with marks or characteristics), a bodhisattva is not a true bodhisattva. To have a mark of self is believe in the existence of an independent and permanent self; to have a mark of others is belief in the existence of independent and permanent being in relation to the self. Likewise, to have a mark of living beings means to believe in the existence of categories of living beings (e.g., species or some other means of classification) that are distinct from one another; to have a mark of life is to believe in the existence of a permanent entity that transmigrates from body to body.

D. Chapter Four

Even the Most Beneficent Practices are Relative

Furthermore, Subhuti, in the practice of charity a Bodhisattva should not dwell anywhere when he gives. He should not dwell in forms when he gives, nor should he dwell in sounds, smells, tastes, tangible objects, or ideas (dharmas) when he gives. Subhuti, thus should the Bodhisattva give: he should not dwell in marks when he gives, his blessings and virtues are incalculable.

Subhuti, what do you think? Can you measure all the space extending eastward?

No, World-honored One, I cannot.

Then can you, Subhuti, measure all the space extending southward, westward, northward, or in any other direction, including nadir and zenith?

No, World-honored One, I cannot.

Well, Subhuti, equally incalculable are the blessings and virtue of the Bodhisattva who does not dwell in marks when he gives. Subhuti, a Bodhisattva should only dwell in what is taught thus.

The Buddha explains that a bodhisattva should not dwell anywhere when giving (which is the first of six paramitas, i.e., perfections) (the other five paramitas are: virtue, patience, joyous effort, concentration and wisdom). Not to dwell anywhere is for the bodhisattva not to think that there is actually any giving occuring when he gives: any and all aspects of the event of giving are ultimately empty. Likewise the bodhisattva should not dwell in sounds, smells, tastes, tangible objects or dharmas, i.e., thoughts. It seems that to dwell on anything when one gives is to dwell on sight, thereby completing the list of the six external objects of the twelve sense fields. Not to dwell on these is to live in the light of the fact that all sense objects (incuding thoughts) are empty, devoid of unconditioned and permanent being. It is repeated that the bodhisattva should not dwell in marks when he gives, meaning that he should not assume that there are any unconditioned and permanent elements in any event of giving. This will produce virtue for the bodhisattva.

E. Chapter Five

Understanding the Ultimate Principle of Reality

Subhuti, what do you think? Is the Tathagata to be seen by his physical marks?

No, World-honored One; the Tathagata cannot be seen by his physical marks. And why? Because the Tathagata has said that physical marks are no physical marks.

Buddha said: Subhuti, all with marks is empty and false. If you can see all marks as no marks then you see the Tathagata.

The Buddha asks Subhuti whether he (the Tathagata) can be seen by his physical marks. In other words, can the Buddha be identified by the thirty-two physical characteristics associated with the Buddha (the body of bliss), such as long slender fingers, forty teeth and a Buddha-crown, a fleshy mound on the crown of a Buddha’s head. Presumably, it was commonly believed that every Buddha had these characteristics. The correct response is that these physical marks are no physical marks, because they are ultimately empty, devoid of independence and permanence. This assertion functions to undermine common, objectifying Buddhist teaching. Everything with marks, i.e., the appearance of own-being is actually empty, which is to say, devoid of own-being and therefore nonexistent. Paradoxically, the one who sees all marks as no marks sees the Tathagata. The Buddha in his ultimate nature, his dharma-kaya (body of essence) is empty, without marks, without distinctiveness; there is only emptiness, in the sense of non-distinctiveness. When one understands that there is only emptiness, one has understood the Buddha as emptiness, i.e., as the Absolute.

F . Chapter Six

Rare is True Faith

Subhuti said to Buddha: World-honored One, will there always be men who will truly believe after coming to hear these teachings?

Buddha answered: Subhuti, do not utter such words! At the end of the last five-hundred-year period following the passing of the Tathagata, there will be self-controlled men, rooted in merit, coming to hear these teachings, who will be inspired with belief. But you should realize that such men will have planted good roots with not just one Buddha, or two Buddhas, or three, or four, or five Buddhas, but will have planted good roots with countless Buddhas; and their merit is of every kind. Such men, coming to hear these teachings, will have an immediate uprising of pure faith, Subhuti; and the Tathagata will recognize them. Yes, He will clearly perceive all these of pure heart, and the magnitude of their moral excellences. Why? It is because such men have no further mark of self, of others, of living beings, or of a life; no mark of dharmas and no mark of no dharmas.

If living beings' hearts grasp at marks, then that is attachment to self, to others, to living beings and to a life. For that reason you should not grasp at dharmas, nor should you grasp at no dharmas. This is the reason why the Tathagata always teaches this saying: My teaching of the Good Law (dharma) is to be likened unto a raft. [Does a man who has safely crossed a flood upon a raft continue his journey carrying that raft upon his head?] Even dharmas should be relinquished, how much the more so no dharmas.

The Buddha explains that, after his extinction, there will be those who believe truly. These are said to have planted good roots with countless Buddhas, meaning that they have accumulated merit in the past in various ways that will result in being in well on the way to enlightenment. It is assumed that there have been many manifestations of the Buddha as the body of essence.The Buddha says that these people will not have any further mark of self, of others, of living beings, or of a life (These were already explained in the commentary on chapter three). In addition, these people have no mark of dharmas and no mark of no dharmas. In this context, dharma means teaching, ideas or intellectual constructs of any sort. The one who understands neither grasps at dharma nor grasps at no-dharma: One neither gives intellectual assent to an idea nor denies that intellectual assent is possible. There is no attachment to either affirmation or the denial of the possibility of affirmation. One might imagine that the doctrine of sunyata means that one must deny the truth of all affirmations, but this is not so. One must no more deny as affirm, because denial assumes a distinction between the subject and predicate, a duality, which, like every other duality is empty of reality. Also to deny an affirmation is an affirmation of its opposite, even if it is only a negation. This is the middle way between affirmation and denial. Dharma is compared to a raft used to cross over to nirvana: it is not true nor is it not true; rather it is instrumentally valuable in attaining the goal of crossing over to extinction.

G. Chapter Seven

Great Ones, Perfect Beyond Learning, Utter no Words of Teaching

Subhuti, what do you think? Has the Tathagata attained the Consummation of Incomparable Enlightenment? Has the Tathagata spoken any dharma?

Subhuti answered: As I understand Buddha's meaning there is no concrete dharma called Consummation of Incomparable Enlightenment. Moreover, there is no concrete dharma that the Tathagata has spoken. And why? Because the dharmas spoken by the Tathagata cannot be grasped and cannot be spoken. They are neither dharmas nor not dharmas. And why? Unconditioned dharmas distinguish worthy sages.

The Buddha asks Subhuti whether he (the Tathagata) has attained Consummation of Incomparable Enlightenment or whether he has spoken any dharma. In other words, the question is whether the Buddha has ever communicated true teaching, including the Buddhist fundamental soteriological teaching, the Four Noble Truths. Subhuti answers that there is no concrete dharma called Consummation of Incomparable Enlightenment and in fact no dharma at all that the Buddha has spoken. (Dharma is being used in this context to mean true teaching.) This is because the dharmas spoken by the Buddha are actually incomprehensible and incommunicable, so that what the Buddha actually teaches is not dharma at all. The result is that there are neither dharmas nor are there no dharmas: one can neither affirm or deny any teaching. The "worthy sage" realizes that dharma is "unconditioned dharma," which is to say that it is dharma that is beyond this realm of conditioned truth, i.e., statements about things that are dependent on other things for their existence, and as dependent are contingent and impermanent. Ultimate truth, if one can call it that, is unconditioned and for that reason inexpressible, because it transcends all plurality, whereas language presupposes plurality. Likewise to speak a dharma wrongly assumes a duality between subject and object, in this case between the speaker and what is spoken, when no such duality exists.

H. Chapter Eight

The Fruits of Meritorious Action

Subhuti, what do you think? If anyone filled three thousand world systems with the seven treasures and gave all away in gifts of alms, would he gain blessing and virtue?

Subhuti said: Great indeed, World-honored One! And why? Because such blessings and virtue are not of the nature of blessings and virtue. Therefore the Tathagata speaks of the many blessings and virtue.

Then Buddha said: On the other hand, if anyone received and retained even only four lines of this Sutra and taught and explained them to others, his merit would be the greater.

Why? Because, Subhuti, from this Sutra issues forth all the Buddhas and the Consummation of Incomparable Enlightenment teachings of all the Buddhas.

Subhuti, what is called the Buddhadharmas are, in fact, no Buddhadharmas.

The Buddha makes the point that his sutra is valuable, more valuable than giving of alms. Nevertheless, he concludes by saying paradoxically that Buddhadharmas are no Buddhadharmas, meaning that what the Buddha teachings is not true teaching, because true teaching is not teachable.

I. Chapter Nine

Real Designation is Undesignate

Subhuti, what do you think? Does a disciple who has entered the Stream of the Holy Life say within himself: I obtain the fruit of a Stream-entrant?

Subhuti said: No, World-honored One. Wherefore? Because "Stream-entrant" is merely a name. There is no stream-entering. The disciple who pays no regard to form, sound, odor, taste, touch, or any quality, is called a Stream-entrant.

Subhuti, what do you think? Does an adept who is subject to only one more rebirth say within himself: I obtain the fruit of a Once-to-be-reborn?

Subhuti said: No, World-honored One. Why? Because "Once-to-be-reborn" is merely a name. There is no passing away nor coming into existence. [The adept who realizes] this is called "Once-to-be-reborn."

Subhuti, what do you think? Does a venerable one who will never more be reborn as a mortal say within himself: I obtain the fruit of a Non-returner?

Subhuti said: No, World-honored One. Wherefore? Because "Non-returner" is merely a name. There is no non-returning; hence the designation "Non-returner."

Subhuti, what do you think? Does a arhat say within himself: I have obtained arhatship?

Subhuti said: No, World-honored One. Why? Because there is no such condition as that called "Arhat." World-honored one, if a holy one of Perfective Enlightenment said to himself "such am I," he would necessarily be attached to self, to others, to living beings and to life. World-honored One, when the Buddha declares that I excel amongst holy men in the Yoga of perfect quiescence, in dwelling in seclusion, and in freedom from passions, I do not say within myself: I am a arhat of Perfective Enlightenment, free from passions. World-honored One, if I said within myself: Such am I; you would not declare: Subhuti finds happiness abiding in peace, in seclusion in the midst of the forest. This is because Subhuti abides nowhere: therefore he is called, "Subhuti, Joyful-Abider-in-Peace, Dweller-in-Seclusion-in-the-Forest."

The Stream-entrant, i.e., the initiant into the Buddhist monastic order, is said not to have entered anything since there is nothing to enter. The same is true of all the other levels of monastic achievement, including "Once-to-be-reborn," "Non-returner" and Arhat. There is no dharma concerning arhantship, so that no one can say that he has attained anything; for there to be attainment, there must first be a self to attain.

J. Chapter Ten

Adorning Pure Lands

Buddha said: Subhuti, what do you think? In the remote past when the Tathagata was with Burning-Lamp Buddha, did he have any degree of attainment in dharma?

No, World-honored One. When the Tathagata was with Burning-Lamp Buddha he had no degree of attainment in dharma.

Subhuti, what do you think? Does a Bodhisattva adorn Buddha-lands?

No, World-honored One. Why? Because adorning Buddha-lands is no adorning; this is merely a name.

[Then Buddha continued:] Therefore, Subhuti, the Bodhisattva, Mahasattva, should develop a pure, lucid mind, not depending upon sound, flavor, touch, odor, or any quality. A Bodhisattva should develop a mind which alights upon no thing whatsoever; and so should he establish it.

Subhuti, this may be likened to a human frame as large as the mighty Mount Sumeru. What do you think? Would such a body be great?

Subhuti replied: Great indeed, World-honored One. This is because Buddha has explained that no body is called a great body.

The Tathagata obtained no dharma while the Burning Lamp Buddha, because there is nothing to obtain; likewise the bodhisattva does not adorn any Buddhaland, because there is nothing to adorn, which is why paradoxically it is called adornment. The assumption is that there have been many manifestations of the Buddha's body of essence and that there are realms where they dwell, i.e., Buddhalands. Therefore it is said that the bodhisattva or the mahasattva (a great bodhisattva) produces a pure heart, which is a heart free from all attachment. This is done by not dwelling in forms (sight objects), sounds, smells, tastes, tangible objects or dharmas (thoughts). The meaning is that he does not take conditioned reality as truly real.

2.1.3. Prajnaparamita Sutra in 8000 Lines

A. Perfection of Wisdom

1. The Six Perfections

Ananda: The Lord does not praise perfection of giving, nor any of the first five perfections; he does not proclaim their name. Only perfection of wisdom does the Lord praise, its name alone he proclaims.

The Lord: So it is, Ananda. For perfection of wisdom controls the five perfections. What do you think, Ananda, can giving - undedicated to all-knowledge be called perfect giving? Ananda: No, Lord.

The Lord: The same is true of the other perfections. What do you think, Ananda, is wisdom inconceivable which turns over the wholesome roots by the dedication of these to all-knowledge?

Ananda: Yes, it is inconceivable, completely inconceivable.

The Lord: Perfection of wisdom is given its name by us from supreme excellence [paramatvat]. Through perfection of wisdom these wholesome roots, dedicated to all-knowledge are given the name of 'perfections.' It is due to this dedication of wholesome roots to all-knowledge this perfection of wisdom controls, guides and leads the five perfections. The five perfections are in this manner contained in this perfection of wisdom, and the term 'perfection of wisdom' is just a synonym for the fulfilling of all six perfections. In consequence, as perfection of wisdom is proclaimed, all six perfections are proclaimed. Just as gems, scattered about in the great earth, grow as all conditions are favorable; and the great earth is their support, and these grow supported by the great earth; even so, embodied in perfection of wisdom, the five perfections rest in all-knowledge, these grow supported by perfection of wisdom; and as upheld by perfection of wisdom are these given the name of 'perfections.' So, it is just this perfection of wisdom controling, guiding and leading these five perfections. (III. 4)

In Mahayana Buddhism, to become a Bodhisattva requires the development of the six perfections (paramitas). These are giving, virtue, patience, joyous effort, concentration and wisdom (prajna). In the prajnaparamita tradition, prajna is centered out as the most important of the six perfections, without which the other six perfections would not exist. To have prajna is to understand the true nature of reality, to see things as they really are. When this occurs, then a person can and will necessarily practice the other five perfections.

2. Wisdom as All-Knowledge

So fond are Tathagatas of this perfection of wisdom, as much do these cherish and protect its process of perfection. Wisdom is mother and begetter, her process of perfection indicates and reveals to us all-knowledge, her perfection instructs us as the way of the world. As her perfection do Tathagatas appear. As her perfection begets, indicates and realizes pure cognition as all-knowing, this perfection indicates to us and as us this world as it is. This all-knowledge of Tathagatas appears as her most profound perfection. (XII)

Moreover Subhuti, due to this perfection of wisdom, Tathagatas quite naturally know immeasurable and incalculable beings as these really are. This comes about through the inevitable dissolution of obscurations. For, herein is simultaneously revealed an increase toward, or away from pure cognition, depending on one's perspective and relationship to these six perfections and Noble Eightfold Path, primarily right intention and right action. Eventually this 'pinnacle' awareness comes about as all-knowledge. This is, however, completely different and other than bits and pieces of knowing formulated of some discursive thought process. This naked realization is of an objectless and purely undifferentiated experience of this uniform non-existence of any individualized or collective own-being within any sentience whatsoever. (XII)

The Lord: So it is, Subhuti. I also do not view Tathagatahood as real, and here I do not take hold of it, do not settle down in this. For this reason all-knowledge also is a state in which one neither takes hold of anything, nor settles down in anything. (XIII)

As one does not fulfill perfect wisdom, neither can one go forth to all-knowledge, so long as one remains trying to appropriate the essentially elusive. In perfect wisdom form, feeling, perception, impulse and consciousness is/are not appropriated. So, the non-appropriation of form, etc., is not form, etc. [the five skandhas), and perfect wisdom also cannot be appropriated. It is thus which a Bodhisattva courses in perfect wisdom. This concentrated insight of a Bodhisattva is called 'the non-appropriation of all dharmas'. It is vast, noble, unlimited and steady, not shared by any of the Disciples or Pratyekabuddhas. All-knowledge cannot be taken hold of, as it cannot be seized through any sign. (I.2)

Wisdom (prajna) is the means by which one sees things as they really are (yathabhutata). It is that "perfection" whereby one penetrates through the illusion of appearance. As in many philosophical systems the assumption is that reality is different from appearance and to know the difference is wisdom. Wisdom is identified with all-knowledge (sarvajnata). From a non-ultimate point of view, one could say that wisdom is the epistemological means by which all-knowledge is reached, which, as the term implies, is to know all things. But one must not take these terms and their different nuances of meaning dualistically, as if wisdom and all-knowledge were two different things. All terms are mere nominal; the one reality is beyond all conceptuality. To have all knowledge is the same as having knowledge of the ultimate non-existence of the multiplicity of individual things of one's experience: "This naked realization is of an objectless and purely undifferentiated experience of this uniform non-existence of any individualized or collective own-being." Ultimately, wisdom understands the emptiness of all things, which is the content of all-knowledge; it is "the non-appropriation of all dharmas." As such, it follows that all-knowledge "cannot be taken hold of, as it cannot be seized through any sign," by which is meant that all-knowledge has no content and cannot be expressed.

B. Dharmas

The term dharma usually denotes a thing or entity, either material or conceptual. In other words, a dharma is an element of experience. Much is said about dharmas in this text as a prelude to understanding emptiness itelf.

1. Emptiness of Dharmas

Subhuti: How is it the Lord says full enlightenment is difficult to know, exceedingly difficult to acknowledge, as here is no one who can get at enlightenment? As emanations of emptiness are all dharmas, no dharma exists which is able to win enlightenment. All dharmas are empty. This dharma for the forsaking of which dharma is demonstrated, this dharma does not exist. As well is this dharma which [314] might have been enlightened in full enlightenment, and this which could have been enlightened, and this which might have cognized [the enlightenment), and this which could have cognized such, -all these dharmas are empty. In this manner I am inclined to think that full enlightenment is easy to win, not hard to win. (XVI)

One recognizes by innate wisdom as pure buddha-nature, all dharmas as without self, give us no hint [about their true nature or intentions]. In the conviction "any and all talk about dharmas [is extraneous to them], consists in mere words, mere conventional expressions, - but these conventional expressions do not refer to anything real, are not derived from anything real, nor are these conventional expressions anything real." In this conviction "any and all dharmas lie outside conventional expression and discourse, and it is not these which are conventionally expressed or uttered." (XXIX)

For no attachment to such objective supports exist in or for Bodhisattvas.' At this, contemplate this true reality of dharmas, which is to say, as all dharmas are without defilement or purification. As all dharmas are empty of own-being, such can 'have' no properties as appear to be these attributes of a living being, such can 'have' no life, no individuality, no personality, such are as illusion, a dream, an echo, a reflected image. As you thus contemplate this true reality of all dharmas, and follow what is spoken of Dharma, you go forth in, and as, perfection of wisdom. (XXX)

As one speaks of a 'Bodhisattva', which dharma does this word 'Bodhisattva' denote? Lord, I see neither this dharma 'Bodhisattva', nor any dharma called 'perfect wisdom'. Since I neither find, nor apprehend, nor see this dharma 'Bodhisattva', nor any dharma called 'perfect wisdom', what Bodhisattva do I instruct and admonish, in what perfect wisdom? (1.2.)

On the assumption that only that which is unconditioned and permanent can be said truly to exist, all dharmas are said to be "without self," by which is meant that all dharmas lack own-being (svabhana). In other words, all dharmas are empty. This is because all dharmas are conditioned and impermanent. For this reason, dharmas have merely nominal existence and can be spoken of so long as one recognizes that such language is merely conventional expression (vyavahara). The Bodhisattva is unattached to all dharmas because they are illusory: "such are as illusion, a dream, an echo, a reflected image." The rejection of all dharmas as having no self or own-being means that even Buddhist dharmas or "entities," such as the Bodhisattva, enlightenment and even perfect wisdom do not truly exist.

2. Dharmas as Having No Marks

The Lord: It is just through essential nature these dharmas are not some 'thing'. Nature for such as these is no-nature, and no-nature are these as nature. All dharmas have one mark only, i.e. no mark. It is for such a reason all dharmas have a character of not being fully known by Tathagatas. Here are no two natures of dharma, but just one single one is nature of all dharmas. And nature of all dharmas is not nature, and no-nature is their nature. It is thus all these points of attachment are abandoned. (VIII)

The Lord: One does not train in any dharma whatsoever. Dharmas do not exist in such a way as people without such training are accustomed to suppose.

Sariputra: So, how do these exist?

The Lord: As these do not exist, so these exist. And so, since these do not exist [avidyamana], these are called [result of] ignorance [[[avidya]]). People not diligent and untrained in such have settled down in these. Although these do not exist, these people nonetheless have constructed all dharmas. Having constructed these, yet attached to two extremes, these people neither know nor see dharmas in their true reality. So these beings construct all dharmas which yet do not exist. Having constructed these, people settle down in two extremes. Depending on this link as a basic fact, beings now construct past, future and present dharmas. Now, once constructed these settle down in name and form. Thusly constructed are any and all dharmas, which yet do not exist, and these beings as such neither know nor see any path as it truly is. In consequence these ones do not go forth from any triple world, and do not wake up to any reality-limit. For this reason ones such as these come to be styled as 'fools'. Such ones as these reveal faith neither to self nor others in the true nature of dharma. But a Bodhisattva does not settle down in any dharma. (I.2)

Beyond these mere appearances, here is no discrimination. Through this non-discrimination are all dharmas fully known to Bodhisattvas. This also is most difficult yet effortless, as Bodhisattvas meditate on all dharmas (at once), and neither realize, nor are cowed, and these meditate thus: "In this way are all dharmas fully known...and thus awakened as full enlightenment, we demonstrate and reveal these dharmas." (XV)

Because they are empty of self, dharmas are without marks except for one mark, which is no-mark. A mark is a distinctive property or essential nature that keeps a dharma apart from other dharmas. If they are really illusory, then dharmas have no essential nature: they are no-nature. If dharmas are really without marks because they are ultimately non-existent, then there is no real apprehension of them. The illusory apprehension of a multiplicity of independent dharmas characterized by marks leads away from an apprehension of true reality, which is emptiness or without marks. People who do not realize this are termed "fools." They will not ever leave samara and enter nirvana: "In consequence these ones do not go forth from any triple world, and do not wake up to any reality-limit." The triple world is the universe whereras reality-limit is a name for the Absolute. The Bodhisattva does not discriminate between one dharma and another, but knows all dharmas insofar as they are non-discriminated. This seems to mean that he knows all dharmas as emptiness, essential nature, i.e., as a manifestation of the Absolute. For this reason Bodhisattvas do not "settle down" in any dharma, which is a way of saying that they do not base on their existence on any dharma. This is unlike the unenlightened people who "settle down in two extremes," which is to say they assume the ultimate existence and non-existence of dharmas and base their existence on that assumption.

3. Dharmas as Isolated

But this non-apprehension of beings, in [[[Wikipedia:Absolute (philosophy)|ultimate]] and] absolute reality, is taught by Tathagatas. And this non-apprehension of beings is inferred from this very isolatedness, and from the isolatedness of any who are so disciplined is the isolatedness of a Bodhi-being inferred. As a Bodhisattva, while this is being taught, does not lose heart, one can know this one courses in this perfection of wisdom. For from the isolatedness of a being is known the isolatedness of form, feeling, perception, impulse, and consciousness...and this the same of all dharmas. Thus is the isolatedness of all dharmas viewed. As this isolatedness of all dharmas is thus taught, a Bodhisattva does not lose heart, and due to this, one courses in this perfection of wisdom.

The Lord: For what reason does a Bodhisattva not lose heart as the isolatedness of all dharmas is thus taught?

Subhuti: Due to isolatedness no dharma can ever lose heart. For one cannot get at any dharma as loses heart, nor at any dharma which makes a dharma lose heart.

The Lord: So it is, Subhuti. It is quite certain a Bodhisattva courses in perfect and natural wisdom as this is being taught, demonstrated, expounded and pointed out...one does not lose heart, is neither cast down nor depressed, is not cowed or stolid, does not turn one's mind away from this, does not have one's back broken, and remains unafraid. (XXVII)

Subhuti: But how can a thought which is like illusion know full enlightenment?

The Lord: Subhuti, do you see the thought which is like illusion as a separate real entity?

Subhuti: No, Lord.

The Lord: Do you see illusion as a separate real entity?

Subhuti: No, Lord.

The Lord: So, as you see neither illusion, nor the thought which is like illusion, as a real separate entity, do you now perhaps see this dharma which knows full enlightenment as something other than illusion, or as something other than the thought which is like illusion?

Subhuti: No, Lord. I do not. In consequence, to which dharma can I point, and say "it is" or "it is not?" To a dharma which is absolutely isolated one cannot attribute "it is" or "it is not." Also any absolutely isolated dharma cannot know full enlightenment. Here now, O Lord, perfect wisdom is absolutely isolated. But any dharma which is absolutely isolated, this is not a dharma which can be developed, nor does this bring about or remove any dharma. So, how can a Bodhisattva, by resorting to an absolutely isolated perfection of wisdom, know full enlightenment? Even full enlightenment is absolutely isolated. As, O Lord, the perfection of wisdom is absolutely isolated, and as full enlightenment is absolutely isolated, how can the isolated become known through the isolated?

The Lord: So it is, Subhuti. It is just as this perfection of wisdom is absolutely isolated that absolutely isolated full enlightenment is known [by this]. But as a Bodhisattva forms such a notion as "the perfection of wisdom is absolutely isolated," this is not the perfection of wisdom. It is thus certain, thanks to perfecting wisdom a Bodhisattva can know full enlightenment, and one cannot know this without resorting to this. The isolated cannot be known by the isolated, and nevertheless a Bodhisattva knows full enlightenment, and does not know this without resorting to the perfection of wisdom.

Subhuti: As I understand the meaning of the Lord's teaching, a Bodhisattva in this way courses in an unfathomable object. (XXVI)

Dharmas are also said to isolated (vivikta), which functions as a synonym for being empty. To be isolated means having no relations with any other dharmas. The point that is being made is that dharmas are isolated because they are ultimately non-existent, although they may appear to be existent; what is non-existent cannot have a realtion with something else that is non-existent. This is why there is a "non-apprehension of beings." In particular, the five skandhas are said to be isolated: " form, feeling, perception, impulse, and consciousness." As non-existent and isolated all dharmas are not apprehended in the sense of being understood as a truly existing entity. The result is that all relations between dharmas thought to exist, as explained in the teaching about conditioned co-production, are illusory; they are isolated from one another because they are not ultimately real. What does not really exist cannot be conditioned because to be conditioned is to have a relation to another dharma. The reason that a Boddhisattva does not lose heart at hearing that no dharma (including that of the Bodhisattva) truly exists is that the dharma of "losing heart" does not exist. Since every dharma is like an illusion it is inappropriate to say that "it is" or "it is not." Unlike an illusion, only real entities can exist or not exist. The conclusion is drawn that a Bodhisattva who is an isolated dharma can ever attained to enlightenment, another isolated dharma, since dharmas are isolated and have not relations. Paradoxically, it is precisely because all dharmas are isolated that there is enlightenment because enlightenment is precisely the realization that there is no separate dharmas called perfect wisdom and enlightenment. Yet paradoxically the one who says "the perfection of wisdom is absolutely isolated" does not have the perfection of wisdom because to make such a statement presupposes that perfection of wisdom is not isolated but really exists.

4. Dharmas Neither Made nor Unmade

In addition, Tathagatas fully know all dharmas as neither made [akrita] nor unmade, as not brought together....Thus perfection of wisdom acts as instructress in these worlds to Tathagatas. And how does perfection of wisdom show up this world for what it is? She shows this world as empty, unthinkable, calmly quiet. As purified of itself she shows up the world, she makes it known, she indicates it, yet does nothing. (XII)

The Lord: Here the Bodhisattva, the great being, thinks thus: 'countless beings do I lead to Nirvana yet here is neither one leading to Nirvana, nor any being led thus'. However many beings one may lead to Nirvana, yet neither has any being been led to Nirvana, nor had any led others to it. As such is this true nature of dharmas, seeing this nature as such, is illusory. Subhuti, just as a clever magician, or magician's apprentice conjures up at these crossroads a great crowd of people and makes these vanish again... What do you think, Subhuti, is anyone killed by anyone, or murdered, or destroyed, or made to vanish?

Subhuti: No indeed, Lord.

The Lord: Even so a Bodhisattva, great being, leads countless beings to Nirvana, and yet not any being has been led to Nirvana, nor has one led others to it. Hearing this exposition without fear is a great thing which entitles this Bodhisattva to be known as 'armed with the great armor'.

Subhuti: As I understand the meaning of the Lord's teaching, as certainly not armed with an armor this Bodhisattva, this great being, is known.

The Lord: So it is. As all-knowledge is not made, not unmade, not affected. Such beings also for whose sake one is armed with great armor are not made, not unmade, not effected. (I.4)

Dharmas are also designated as neither made not unmade, i.e., destroyed. If they are ultimately non-existent insofar as they are empty, without marks and isolated, then it is inappropriate to say that dharmas come into being or go out of being. Frequently, dharmas are compared to an entity that a sorcerer conjures up. Such an illusory being did not really come into being because it does not truly exist, nor is it destroyed for the same reason. This applies even to the dharma known as "all-knowledge." Likewise, there is no dharma known as a Bodhisattva nor dharmas known as the countless beings that he leads to nirvana. In fact there is no true becoming but only the eternal calmness of unthinkable emptiness.

5. Metaphors for the Ontological Status of Dharmas

In order to explain the ontologial status of dharmas, several metaphors are used. The intention is to show that non-existence of all dharmas: even though dharmas are something the something that they are does not warrant being given the title of an truly existing entity. This is because dharmas lack own-being, since they are conditioned and impermanent. Dharmas are compared to objects in a dream, illusions that are magically conjured up, echoes, shadows, reflected images, the moon in reflected the water, mirages and the legendary village of the Gandharvas (See VIII 198; IX 201, 205; XXX 484; IX205; XXVI 442; XX 484).

C. The Enlightened Attitude towards Dharmas

1. No Seeing, Apprehension, Taking Hold of or Attainment of Dharmas

Subhuti: No, Lord. I do not see any real dharma which is at any time predestined to full enlightenment. Nor do I see any real dharma which is known by the enlightened, which can be known to these, or by means of which these can even reveal full knowledge. It is such as any and all dharmas cannot be apprehended, that this does not occur to me to think, "this dharma is known to the Enlightened, this dharma can be known to such as these, by means of this dharma these recognize full knowledge." (XXII)

As a result of emptiness, isolatedness and quietude these cannot be apprehended. The lack of a basis of, or for apprehension in any and all dharmas, this is called 'perfect wisdom.'(VII)

Subhuti: As thus in ultimate truth and as things stand, no dharma is apprehended as real, what is this dharma which is turned away from full enlightenment? (XVI--319)

He takes true nature of dharmas as his standard, and resolutely believes in signlessness such as he neither takes hold of any dharma, nor apprehends any dharma which he even might appropriate or release. He does not even care about Nirvana. (1.2)

Subhuti: I do not wish for any attainment of any unproduced dharma, nor reunion with one. Further, does one attain an unproduced attainment though unproduced dharma? (I. 6)

Since all dharmas are empty of own-being, without self, have no marks and are isolated, it follows a Bodhisattva should not think that dharmas exist truly as things existing independently of the mind for which they are objects. This is expressed variously as there being no seeing, apprehension or attainment of a dharma. This would be described in Western philosophy as nominalism, that words are only names and do not signify real things. This even includes the dharmas of perfection of wisdom, all-knowledge, enlightenment or Bodhisattvahood.

2. No Settling Down in Dharmas

People not diligent and untrained in such have settled down in these. Although these do not exist, these people nonetheless have constructed all dharmas. Having constructed these, yet attached to two extremes, these people neither know nor see dharmas in their true reality. So these beings construct all dharmas which yet do not exist. Having constructed these, people settle down in two extremes. Depending on this link as a basic fact, beings now construct past, future and present dharmas. Now, once constructed these settle down in name and form. Thusly constructed are any and all dharmas, which yet do not exist, and these beings as such neither know nor see any path as it truly is.... For this reason ones such as these come to be styled as 'fools'. Such ones as these reveal faith neither to self nor others in the true nature of dharma. But a Bodhisattva does not settle down in any dharma. (I.2)

Perfection of wisdom does not follow after duality of opposites, as such does not settle down in any or all dharmas. Perfection of wisdom is undifferentiated, as all dharmas are still but speciously indicated.....Perfection of wisdom is undiscriminated, as this is basic identity to all which is discriminated. Perfection of wisdom is infinite, as any nature of dharma is unlimited. Perfection of wisdom is unattached, as this is non-attachment to all dharmas....Perfection of wisdom is Empty, as any or all dharmas are not apprehended. Perfection of wisdom is not-self, as here is no settling down in any or all dharmas. (IX)

The Lord said to Ananda: In this same way, Ananda, all dharmas do not come within the range of vision. Dharmas do not come within the range of vision of dharmas, dharmas do not see dharmas, dharmas do not know dharmas. All dharmas are of such a nature as these can be neither known nor seen, and are incapable of doing anything. All dharmas are inactive, these cannot be grasped, as these are as inactive as space. All dharmas are unthinkable, similar to illusory men. All dharmas are unfindable, as these in a state of non-existence. As one courses thus a Bodhisattva courses in perfect wisdom and does not settle down in any dharma. [466] (XXVIII)

Perfection of wisdom is unconditioned, as all dharmas are impermanent and merely an indication of such as this is. Perfection of wisdom is as space, as any nature of dharma is identical as impermanence. Perfection of wisdom is empty, as any or all dharmas are not apprehended. Perfection of wisdom is not-self, as here is no settling down in any or all dharmas. (IX)

What does not exist, in truth cannot be embraced. One thus learns not to even think to embrace anything as a result of this cognition and vision. Non-embracing is "already established" as of itself and timelessly self-existent. Once revealed, what comes about is our realization of Such. All dharmas are non-embracing for such cannot be embraced, and these are also non-arising as lacking attributes such as, coming into being (to begin with!), and consequently dwelling in time, duration and place, and ceasing to exist. (XV)

And perfect wisdom does not cling to any dharma, nor defile any dharma, nor take hold of any dharma. Any and all dharmas neither exist nor are any got at. As it is not apprehended perfection of wisdom is without any stain. (IX)

One does not go near any dharma at all as all dharma are unapproachable and unappropriatable. So, a Bodhisattva purely cognizes and is as undifferientiated concentrated insight 'Not grasping at any dharma' by name or appearance, and regardless whether vast, noble, unlimited and steady, not shared by any of the Disciples or Pratyekabuddhas. (I. 2)

When one courses thus, a Bodhisattva does not generate attachment to anything, from form to all-knowledge. For all-knowledge is unattached, it is neither bound nor freed, and here is no-thing whatsoever which can rise above or beyond this, such as this is, even unto any self. It is thus, Subhuti, Bodhisattvas course in perfect wisdom through rising completely above any and all attachments. [VIII 196]

Because they are not what they appear to be to the unenlightened, a Bodhisattva does not "settle down" (anabhinivesa) in any dharma. There should be no conviction that a dharma has reality, so that a Bodhisattva should take no interest in a dharma and form no attachment to it on the assumption that it truly exists. This applies to dharmas that are thought to exist and those thought not to exist, i.e., the two two extremes of existence and non-existence. The same thing is meant when it is said that no embracing or taking hold of, grasping at or attachment to any dharma is possible. It also follows that even perfection of wisdom does not take hold of any dharma in the sense of being defined by a set of beliefs expressed propositionally. Perfect wisdom is no dharma, nor does it rely on any dharma, since all dharmas are non-existent. It is the absence of all dharmas.

3. No Discrimination (vilkalpa)

Subhuti: No, indeed not, Sariputra, as the Tathagata is beyond reflections and discriminations. Empty awareness beyond any objective support, raises to, or rather reveals result as neither deed nor thought, as such simply cannot. A deed 'arises' only with an objective support as basis and not without one [even if such is merely assumed, as in the dream where, say, one kills another, and upon waking carries on as if having actually killed]. This result of false view, raises or reveals the assumption to reality, even though a mirage, a phantom spector now in both this objective reality, as well as the dream-world. This type of thinking arises with only a (personally) untested presumption for its objective support, not without one (and sadly in most cases, habitually left beneath any discursive perusal). As 'intellectual' acts can only refer to dharmas such as are seen, heard, felt, or known, in this unchecked thinking all results necessarily do miss the mark, and are inaccurately assumed as fact and truth, and thusly projected out onto the myriad worlds as such. (XIX 358)

Flashes of enlightening and pure undifferentiated awareness, identical with absolute emptiness, this dark as pitch notion, infinite as space. (XII)

In meditation, the Boddhisattva is characterized by an awareness that makes no discriminations, which means a consciousness in which no distinctions are found, especially the distinction between subject and object. In such a meditative state, the usual distinctions of dualistic thinking are discovered to have no basis in reality and are said to be without objective support. They are compared to the objects experienced in a dream. All deeds and thoughts are found to be without support, i.e. without any basis in reality. Consciousness freed from dualistic thinking is described as pure undifferentiated awareness, absolute emptiness and like space, unbounded and empty.

D. The Absolute

The Absolute is the truly real, and for this reason is infinite in the sense of being without limits that would define it. As such it is beyond all conception, which is why it is often called emptiness: it is empty of all marks or characteristics. The Absolute is unconditioned and permanent, the negation of all dharmas, and even the negation of the negation. All conceptual distinctives and barriers are dissolved so that there remains only pure consciousness with no content, identical to the Absolute. Such an insight is all-knowledge realized through perfect wisdom by means meditation; it is realized when the mind is free of all dualistic consciousness, having transcended not only the distinctions between dharmas as objects but even between the dharmas of subject and object.

1. Emptiness

The Lord: Are not all dharmas described as "empty"?

Subhuti: Yes, and simply so, as quite empty Tathagata describes all dharmas.

The Lord: And being empty, such are also inexhaustible of emptiness. And what is emptiness is also immeasurableness. So here and now, according to ultimate reality, neither distinction nor difference is apprehended between dharmas, nor can any 'between' dharmas even begin to be assumed. As talk these are described by Tathagata. One merely talks as one speaks of "immeasurable", or "incalculable", or "inexhaustible", or of "empty", or "signless", or "wishless", or 'this Unaffected", or "Non-production", "no-birth", "non-existence", "dispassion", "cessation", "Nirvana". This exposition is being described by Tathagata as the consummation of demonstrations. (XVIII)

The Lord: Well said Subhuti. Surely, you bring up unfathomable positions as you want to hear discoursing on this subject as well. "Unfathomable", Subhuti, is Emptiness which is a synonym of Signlessness, Wishlessness, Uneffectedness. Such is Unproduced, as in...No-birth, Non-existent, Dispassioned of Cessation, Nirvana and Departing. [342]

Perfection of wisdom is as space, as any nature of dharma is identical as impermanence. Perfection of wisdom is Empty, as any or all dharmas are not apprehended. Perfection of wisdom is not-self, as here is no settling down in any or all dharmas. Perfection of wisdom is markless, as here is no reproduction in dharmas.

Perfection of this is of total emptiness, as endless and boundless....This is perfection of Emptiness, of the Signless, of the Wishless, as the three doors to deliverance cannot be apprehended. (IX)

Sariputra: This thought which is no thought, is this something which is?

Subhuti: Is here existing, or can one apprehend in this state of absence of thought either a 'here is' or a 'here is not'?...

Sariputra: No, not this.

Subhuti: Is this now a suitable question which the Venerable Sariputra asks whether this thought which is no thought is something which is?

Sariputra: So, what is this absence of thought?

Subhuti: It is without modification or discrimination. (I.2)