The Post-Soviet Treasure Hunt: Time, Space and Necropolitics in Siberian Buddhism by Anya Bernstein

Acknowledgments: I thank Bruce Grant, Donald Lopez, Fred Myers, Katherine Verdery, GrayTuttle, Michael Lempert, Nica Davidov, and three anonymous CSSH reviewers for reading versionsof this paper and offering many helpful insights and suggestions. The field research for the paper was supported by the Wenner-Gren Dissertation Fieldwork Grant and Fulbright Fellowship. Thewriting was supported by the Michigan Society of Fellows Postdoctoral Fellowship and Mellon/ ACLS Dissertation Completion Fellowship. An earlier draft was presented at the Rubin Foun-dation/TBRC Scholars Seminar, in 2009. All English translations from Russian are my own.

In September 2002, Buddhist lamas of the Ivolginsk monastery in the post-Soviet Republic of Buryatia in southern Siberia accompanied by independent forensic experts performed an exhumation of the body of Dashi-Dorzho Itige-lov, the last head lama from the time of the Russian empire, who died in 1927.[1] The body of the lama, found in the lotus position, allegedly had not deterio-rated, and soon rumors spread that the lama was alive and had returned to Buryatia, as he had promised he would. According to the stories told by senior monks, before his death Itigelov asked to have his body exhumed thirty years after. He was first exhumed in 1955 (a little short of thirty years) by his relatives and lamas, in secret for fear of being discovered by the Soviet authorities. As expected, the body was intact, so they reburied him.[2] It was only after the final exhumation in 2002 that the lamas installed the body in a glass case in the Ivolginsk monastery, which very soon became an international and domestic sensation, with articles appearing in The New York Times, and Russian politicians and oligarchs rubbing shoulders with droves of pilgrims and tourists to catch a glimpse of the lama.

While Itigelov is perhaps the best-known lama kept under glass after his return to the land of the living, similar exhumations were performed for most of the previous Khambo Lamas, although no other “incorruptible” bodies were found. Instead, subsequent excavations revealed various objects, such as Buddhist ritual implements referred to as “treasures”(Rus.sokrovishcha)and accorded revelatory status. Treasures were found in places as diverse as ruins of former monasteries and remote areas of the forest. Sometimes such findings would trigger other miraculous events, such as the appearance of religious imagery in natural phenomena, accompanied by visions and prophesies.What all of these phenomena had in common was their perceived connection to certain charismatic Buddhist personalities of the past: for example, the treasures would spring up near their former places of residence or supposed burial. Furthermore, in the local object-ideology, the treasures were believed to have a certain kind of agency in the sense that they “chose” when to reveal themselves. Not only was Itigelov believed to have “come back,” but also statues, books,lamps, and other attributes pertaining to religious life were thought to have “returned.” In this article, I propose to examine this hunt for treasures as a kind of post socialist necropolitics that aims to re-consecrate the post-Soviet landscape and create renovated cosmologies of time and space. I argue that,for participants, this effectively shifts the locus of “authentic” Buddhism from India and Tibet to contemporary Buryatia, strengthening assertions of cultural sovereignty.

Necropolitics, both in the sense of controlling mortality and as related to the activity and discourses around dead bodies, has been especially prominent in the studies of socialism and post socialism. In 1924, the Immortalization Commission, a group of Soviet scientists, revolutionized what might today still be considered the traditional perspective on a leader’s “two bodies” (Kantorowicz1957). Not only was Lenin’s body politic declared immortal through the ubiquitous slogan “Lenin lives, Lenin lived, Lenin will live!” but also his body natural was made eternal though experimental techniques of embalming. Influenced by contemporary futuristic theories claiming that technology would soon enable the resurrection of the dead, scientists considered it their moral duty to preserve great historical figures.[3] Thus, after Lenin, Stalin’s embalmed body entered the same mausoleum in 1953, while great leaders of other socialist countries were sent to Russia for mummification (Buck-Morss 2000: 78 – 79).

While socialism was characterized by the drive to immortalize “great bodies,” one of the most important processes in the post socialist period was that of exhumations and reburials. In the mid-1990s, calls to remove Lenin from the mausoleum and give him a “proper human burial” created a controversy on the Russian political scene, one which is still unresolved. Similarly, other countries in the post socialist bloc have been swept by what Katherine Verdery called a “parade of dead bodies.” Statues were toppled, and famous corpses and bones moved around — some were removed from their former places while others were brought from abroad to be reburied at home with great fanfare (Gal 1991; Todorova 2009; Verdery 1999). Why is all this activity around dead bodies happening in the post socialist period? Verdery argues that rather than being simple metaphors of the death of the communist system, these “dead-body manipulations” are crucial to the central transformations of postsocialism: they reconfigure not only the notions of authority, the sacred, and the moral order, but also those of time and space itself, as the past is being revisited and the present reoriented (ibid.: 33 – 53).

While many socialist corpses are well known, others, despite being crucial for their local communities, remain more obscure to both the broader public and scholarly investigators. When I found out about the exhumations of lamas taking place in post-Soviet Buryatia I was not surprised, given that dead bodies are ubiquitous in so many diverse postsocialist contexts. Not until I lived in Buryatia during several extended research trips between 2001and 2008 did I begin to discern a distinctive mix of practices and ideas,which, while inevitably influenced by broad notions of postsocialist necropolitics, manifest a characteristically Buddhist political theology.

The struggle for legitimacy and religious sovereignty has been the single most important process in Buryatia since the beginning of the postsocialist religious revival in the wake of the Soviet collapse in 1991, and active debates continue today. Should Buryat Buddhism be understood as adhering to a “Tibetan” model, one most recently advanced through pilgrimages by monks and well-funded laypersons to Tibetan monasteries in India? Or, as ethnonationalists argue, should it downplay its international ties to assert itself as a truly independent “Buryat” religion? Over the last decade, the official head of Buryat Buddhists, Khambo Lama Damba Aiusheev, has repeatedly expressed his dislike for the proliferation of Tibetan and other Buddhist “missionaries” in the republic, arguing that Buryat Buddhism is fully “autocephalous”(avtokefal’nyi). That is to say, it should be allowed to develop independently of the influence of other traditions. This is also Moscow’s view on the matter, which has been highly discouraging of Buryats’ international connections, with Putin’s 2000 National Security Policy calling for “counteracting the negative influence of foreign religious organizations and missions” (Ukaz Prezidenta RF 2000).[4] Despite this, since the mid-1990s Buryatia has found itself the home of a small but influential community of Tibetan émigré lamas who have relentlessly tried to bring Buddhism in Buryatia in line with what they believe to be an “authentic” Tibetan tradition. Likewise, during the last decade many Buryats, including monks and advanced lay practitioners, traveled to study Buddhism abroad and, upon their return, questioned the form the Buddhist revival has taken in the republic. The treasure hunt, I believe, is a local response to this dilemma.

Various objects such as relics of famous monks, auspicious images found on rocks, and ritual implements interred during Soviet times, create new sacred geographies and historiographies. These recent geo-imaginary formation sserve to physically inscribe Buddhism into the land, as evidenced in the continuing search for and discoveries of treasures. Given that treasures are believed to be objects with a certain kind of agency, defined here in its primary philosophical sense as the capacity to act in the world, Buddhists approach these objects as potential expressions of past intentions, such as those of previous lamas. Translating these emic beliefs into the language of anthropological theory, one can say that treasure objects possess what Gell called “distributed personhood,”where the object is viewed as an extension of a person (1998: 21;see also Strathern 1990 on partible persons). Gell provides us with a famous example of one of Pol Pot’s soldiers who distributes elements of his own agency in the form of landmines and argues that the mines present an example of a “second-class agency which artefacts acquire once they become enmeshed in a texture of social relationships” (1998: 17). Nonetheless, Gell makes a clear distinction between the “primary intentional agents” (humans) and their “secondary artefactual forms” (objects) (ibid.: 21). Buddhists, on the other hand, who already seem to have their own object-ideology in place, locate agency in the space between the deeds of enlightened beings and the capacity of the devout to perceive them. Buddhist treasure objects, in particular, relics — which in this case include both the actual physical remains of a prominent lama and objects that came in contact with him — are invested with some of the intentionality of their owners. While some Buddhist elites have instrumentalized the treasures to strengthen their own political platforms,the pursuit of buried treasures has been important for many in Buryatia in being seen as part of their effort to move from a position of marginality in the Buddhist world to one of greater prominence and to strengthen sovereignty claims within the Russian Federation and in the transnational Tibetan world.

During my field research I came across many kinds of treasures. They can be classified by type (ritual object, text, body) or by their location (ruins of former monasteries, caves, forest, hollows of trees). Some were “anonymous” in the sense that, at the time of their discovery, their importance was unclear. The treasures that gained great national fame were those linked to the agency of famous Buddhist personalities believed to have predetermined their appearances. While Itigelov’s body is viewed by many as the ultimate repository of Buryat Buddhist sovereignty, in more specific ways the stories of his multiple incarnations and reincarnations authenticate a direct transmission of Buddhism

from India to Buryatia, lengthening Buryat religious history and creating new ways to conceptualize time. Other discoveries reorder space, as evidenced by the discovery of a ritual object related to the famous lama Soodoi, which, as I will explain, transformed one of the most remote “shamanic” Buryat regions into a prominent pan-Buryat and, arguably, international Buddhist pilgrimage site. Finally, ruins, a particular kind of place in the midst of which treasures often “reveal” themselves, become dramatic instances of places that condense temporalities with crucial links not only to the past but also to the future.

TIMELINE RE-EDITED

Scholars of socialism have observed that many post-Soviet historical revisions reveal an interesting conception of time in which history may be visualized as a timeline that can be edited, with certain time periods snipped and discarded,while other, disparate periods, such as the pre-communist 1900s and post-communist 1990s, can be “pasted” together. Such excisions go beyond simply emphasizing one period over another and reveal a new understanding of time as no longer fixed and irreversible (Verdery 1999: 112 – 16). In a similar vein, many Buryat religious adepts now view the Soviet period as nothing but a brief intermission in the otherwise triumphant Buddhist march northwards, often citing the Tibetan example of Buddhist decline during the ninth and tenth centuries. While this might seem to be a linear progression,on a larger scale postsocialist Buryats reject the linear timeline of socialist progress in favor of a more cyclical, messianic conception of time, viewed as an alternation of global Buddhist declines and revivals, advents and departures of various Buddhas — most commonly, the “historical” Buddha is viewed as the fourth, while the fifth one, Buddha Maitreya, is eagerly awaited — as well as births and deaths of prominent enlightened beings. The socialist suppression of Buddhism in Buryatia is viewed as part of this cyclical trajectory. Excisions of time produce what Erik Mueggler called an “oppositional practice of time” that undermines official temporalities (2001: 7).[5]

“Have you heard that there was only one single monk left in Tibet for almost two centuries?” one Buryat monk questioned me. “And yet they recovered. We only had seventy years of atheism and suppression, and some of our lamas survived the purges. We will recover. Many today blame us for not being what proper monks ought to be. In that sense, we are not really monks, we are builders. A foundation should be laid before proper Buddhism can take off. We are just the ones who create the necessary conditions (predposylki) for the future.” This self-presentation by monks as “ builders ”and not “proper monks” is worth pausing over, since it displays a particular politics of time advanced by postsocialist Buryats in response to challenges from the transnational Buddhist establishment. Buryats’ international co-religionists often look down on them for having a “corrupt” version of Buddhism. The Geluk school of Tibetan Buddhism, established in Buryatia in the early eighteenth century, is based on celibate monasticism. However, for various reasons beyond the scope of this article, celibate monasticism never took root either in Mongolia or Buryatia, and its lack presents the greatest challenge to Buryat Buddhist legitimacy; they must “catch up” in order to reach an ideal state of Buddhist development. Many contemporary Buddhists blame the Soviet period for this state of affairs, producing this distancing discourse that is a curious inversion of the characteristic Soviet discourse of time and development.

In a recent work, Susan Buck-Morss argued that the Russian Revolution challenged the notion of space (territory) as the single determinant of sovereignty and produced a discourse of time, which in socialist states became a distinctive arena for the exercise of sovereign power (2000: 38). The revolution was understood as an advance in time, supposed to conquer backwardness,reversing the European geopolitical understanding of history as “space over time.” As Lenin famously proclaimed in 1918, commenting on his willingness to sign the treaty of Brest-Litovsk that ceded Ukraine to the Germans: “I want to concede space…in order to win time”(ibid.: 24). Space was for socialist regimes only a means to an end: the territorial isolation provided a possibility to “catch up” with the industrial West. In Stalin’s famous iteration, what had taken Western Europe one hundred and fifty years the USSR had to cover in just ten. While everyone in Russia had to speed up time, “tearing along on the fast locomotive of history,” indigenous peoples in particular had to “race like the wind,”skipping entire historical eras (conceptualized as evolutionary stages in the development of mankind) in order to emerge from their “backwardness” into socioeconomic modernization (Slezkine 1994: 200).

This formula, Buck-Morss notes, was somewhat reversed in the latter years of socialism, when indigenous peoples started questioning Soviet logics of sovereignty. These claims fashioned alternative discourses of time in which Soviet modernization was judged as reckless and destructive for both the environment and native cultures (Buck-Morss 2000: 39). While many former Soviet republics advanced their claims to sovereignty on a territorial basis,that was impossible in Buryatia, where by the fall of the Soviet Union Buryats were outnumbered by the Russian majority, constituting only 24 percent of the population. Although Buryat elites seem to have abandoned the idea of political sovereignty in the early 1990s (Hamayon 2002), assertions of cultural sovereignty — understood as self-determination, rights to land and resources, language preservation, as well as the more general desire to be fully in control over their own cultural politics — are increasingly vital in this age of Russian authoritarian revival and centralization of power.

For many religious leaders and adepts, such sovereignty hinges on their Buddhist religion, which many view as the most important indigenous heritage. While Buddhism has been officially recognized as one of Russia’s four official religions, international recognition of Buryat Buddhism as a distinctive tradition has lagged due to Buryats’ marginalized position within the transnational Tibetan Buddhist world, which often regards them as “backwards” Buddhists steeped in superstition and shamanism. This lack of recognition in the transnational arena, in turn, undermines Buryats’ claims to cultural sovereignty within the Russian Federation. It is in response to these challenges, I suggest, that Buryats developed a distinctive practice of time to advance and justify their assertions of religious and cultural autonomy. It is similar to pre-revolutionary socialist discourse in that it acknowledges its own “backwardness” (“we are not proper monks”), although the desired ideal is no longer that of modernization but that of “traditional” Buddhist societies (often associated with Geluk celibate clergy). Yet, the blame for this backwardness is placed on the “communists,” who impeded Buryat Buddhist development at the peak of its glorious age in the early twentieth century. To “catch up” in time therefore requires spatial isolation and the exclusion of more established “foreign” religious traditions.

This discourse also emphasizes a radical shift in spatial arrangements of the Buddhist world in general. The phenomenon of treasures is locally viewed as proof that, with time, the Buddhist center of gravity will move north to Buryatia and Mongolia as Tibetan Buddhism is marginalized due to the unfavorable conditions for Buddhists in Chinese Tibet and exile settlements in India. In other words, given time for development, world Buddhism will be recentered.6[6] These geo-imaginary formations are materialized through the agency of objects that began bursting forth from the earth, thus grounding these seemingly abstract space/time cosmologies.

The fact that my ethnographic consultants were inclined to think in these specific historical terms prompted me to consider the history of the decline and revival of Buddhism in medieval Tibet. At first glance this seems an unlikely intertext for postsocialist Buryatia, but a closer look at some of the interpretations of that period convinced me that following my Buryat interlocutors in thinking about this geographically and historically remote case might provide an insight into the transformations of time and space in contemporary Siberia. When my monk interlocutor drew a parallel between the current Buryat Buddhist revival and the similar period in medieval Tibet, what I found most striking was the prominence in the latter of the Tibetan “treasure” movement,which also emerged during a renaissance following a period of decline. What specific forces propel these objects to emerge from the ground during periods of religious renovation?

THE DEEPENING OF HISTORY

Analyzing the rebirth and reformation of Tibetan Buddhism after the catastrophic collapse of the Tibetan empire in the ninth century, Buddhist studies scholar Ronald Davidson raises the question of how is it that Tibet, until then an extremely peripheral place in the Buddhist world, managed to displace India itself as the source of ideal Buddhist practice and become a premiere destination of pilgrims from much of Eurasia, as well as Indians themselves(2005). Davidson focuses on the several centuries of cultural flow between Tibet, India, China, and the Mongols in the period known as “Tibetan Renaissance”(950 – 1200 CE) and unravels how complex historical interactions between Tibetan indigenous spirituality and innovations brought from the more developed Buddhist countries resulted in development of what is now taken for granted as “original” Tibetan Buddhism. Especially interesting in relation to the Buryat situation are the indigenization strategies adopted by Nyingma (literally,“ancient”), the tradition of Buddhism dominant in Tibet before its collapse. Faced with the challenge of the new religious influences that inundated Tibet during the renaissance period, the older school employed particular strategies of authenticity that simultaneously allowed for a production of new religious forms while linking them to imperial legacies and lineages (ibid.: 210 – 44). The most distinctive feature of the Nyingma school is the tradition of “treasure texts” (gter ma), texts believed to have been written at an earlier time but buried underground until the time to reveal them has come, like timed-delayed capsules guided by destiny. The discovery events are believed to be predetermined by the concealer of the treasures and are performed by a particular kind of religious practitioner known as “treasure discoverer”(gter ston), who then “translates” them into forms comprehensible to his contemporaries.

Treasure texts are usually seen by scholars to be a strategy for producing new legitimate indigenous texts while avoiding the conundrum of mandatory Indic origin for all authentic Buddhist scriptures (Gyatso 1993). Texts, however,should be viewed in relation to other kinds of “treasures” (literally, hoards of precious materials buried during the time of unrest) commonly found at Tibetan imperial sites during the time of Tibetan renaissance, such as statues, bones, and ritual implements (Davidson 2005: 213).[7] As the Tibetan popular imaginary came to conceive of the empire as the “golden age,” the link between the found treasures and fascination with old dynastic realms became a major, additional source of legitimacy. With the end of the Cultural Revolution in China in 1976 and the start of the revival of Tibetan Buddhism, the treasure movement has also been revitalized by the contemporary Nyingma leaders in present-day eastern Tibet, as artifacts and scriptures have started appearing during excavations of ruined temples (Germano 1998).[8]

As I perused these accounts of imperial collapses, religious declines and revivals, and border crossings, I was struck by their resonance with present day Buryatia. The Buryats’ own hunt for treasures such as relics, ritual objects, and texts buried during the Soviet times relates the present to the imperial past, especially the “golden age” of Buryat Buddhism believed to have been achieved under the late Russian empire, when many important indigenous intellectuals and religious leaders came to prominence. Similar to medieval Tibet, where the treasure movement was launched by the “old” school that viewed itself as a legitimate heir to the glorious imperial Buddhist period, in Buryatia the organization that claims legitimacy from the “golden age” of Buryat Buddhism — viewed by many as the early years of the twentieth century — is the Buddhist Traditional Sangha of Russia, further referred to as “the Sangha.” Just like the Nyingma school, which felt threatened by the new influences coming directly from India, the Sangha feels endangered bythe modern Tibetan currents coming to Buryatia through traveling Tibetan lamas and Buryat pilgrims and monks visiting India. Tellingly, it was the Sangha that launched the postsocialist Buryat treasure hunt.[9]

One important difference between Tibetan treasures, or terma, and Buryat treasures is that terma were believed to be hidden by an Indian master: in this sense they are not really “indigenous” but a case of magically discovering a foreign source in the native soil. In Buryatia, on the contrary, treasures are connected to famous local lamas. Still, the Indian connection is of utmost importance and, as will be shown, it is usually produced through viewing these local Buryat saints as incarnations of Indian masters. What both Tibetan and Buryat treasures also have in common is that upon their discovery both are viewed as if they were “meant” to be found at that particular time, and therefore are accorded revelatory status.[10] Similar to terma, Buryat treasures are believed to act as time-delayed mechanisms that activate during particularly “dark” times to deliver messages from the past. Specifically, in Buryatia, the agency of these treasures manifests itself as calls to action related to the spread and revival of Buddhism in a particular area. For example, if a treasure is found at a particular time at the ruins of former monasteries, these monasteries then get restored in an extremely efficient manner. Treasures are also often found near the former residences of particularly significant religious personalities of the past, near important shamanic sites, or areas, which, for one reason or another, are not yet controlled by the Sangha. The treasure finds not only signal that the time for restoration is ripe but also serve to authenticate new religious institutions through their physical link to the past. In what follows, I demonstrate how these treasures serve as an important factor in the Sangha’s consolidation of power, as it attempts to bring the whole of Buryatia under its control, reawaken the faith lost under socialism, and assert the authenticity of Buryat spirituality.

BUDDHIST NECROPOLITICS

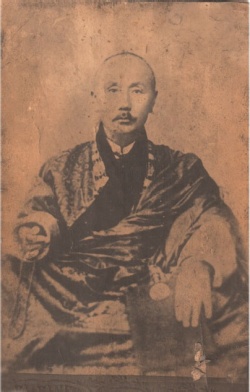

Much has changed in Buryat Buddhism since the exhumation of Itigelov’s body in 2002. First, a popular cult immediately developed around his body. Itigelov is believed to grant one’s most intimate wishes and instantaneously correct one’s karma. It is said that diseases are healed upon touching his hands, and people are reported to have left their crutches at the temple. He has been compared to Tarkovskii’s famous room in the Zone depicted in the film “Stalker (adapted from the Brother Strugatskiis’ novel) — a place every-one is trying to reach, where only one’s deepest subconscious desires are fulfilled. Pessimists worry that all sorts of unbalanced persons and “saviors of humanity” might try to abuse Itigelov’s powers. These anxieties are com- pounded by paranoid fears that either the Kremlin or a mad scientist in search of the Nobel Prize for understanding immortality might buy or steal Itigelov’s body. Until recently, it was held on the second floor of the main temple at Ivolginsk and was brought into the main temple area on major Buddhist holidays. During other times, temple visitors could touch a thread tied to his body that descended through the ceiling. In 2008, a new temple called the Palace of Itigelov opened, and it is now considered his residence. The construction of this palace, which started in 2003, is referred to as “people’s construction”(narod-naia stroika), since it was built with private donations and volunteer labor (Basaev 2008) (see image 1). [[File:Vello_vaartnou_and_his_guru_munko_lama.jpg|thumb|250px|Vello Vaartnou and Munko Tsybikov in Ivolga Monastery)] While for most believers Itigelov’s body is a vehicle of hope and enthusiasm, for the Sangha it became a new foundation of its legitimacy, which especially strengthened the institution of the Khambo Lamas. To make sense of this phenomenon, let us take a closer look at the history of the Sangha. Although it claims to be heir to the Buryat Buddhist “golden age,” technically the Sangha is a successor to the Central Spiritual Board of Buddhists (Tsentral’noe dukhovnoe upravlenie buddistov), a Soviet-era organization formed in 1922and reorganized in 1946. During the early 1990s, when Buddhist structures began to be reestablished in Buryatia, Munko Tsybikov, a lama from the older generation of Buddhists who was imprisoned in Stalin’s camps, was elected as the Khambo Lama. After his death, the Board of Buddhists was ridden with conflicts, with two Khambo Lamas in four years elected and then dismissed due to their “unsuitability to the office held” (Zhukovskaia 1997: 10). In 1995, a conflict arose among the Buddhist clergy when Khambo Lama Choi-Dordzhi Budaev was removed from office on charges of embezzlement. In his place, a little-known young lama, Damba Aiusheev,a former physical education teacher who had subsequently studied in Mongolia to become a lama, was elected as the 24th Khambo Lama and the head of the Board of Buddhists (see image 2).

At first, no one expected this inexperienced but eager lama to keep his office for more than a few years. At this time also the Board of Buddhists’ authority was being greatly undermined among lay Buryats due to widespread corruption and financial scandals. The 1990s were characterized by public disillusionment with the behavior of the Buddhist clergy, which diminished the lamas’ authority and led to widespread rumors about their inappropriate behavior. For example,the belief in the immortal soul that can leave the body at will, widespread among Buryats, is often criticized by more orthodox Buddhists as a shamanic “superstition,”and one story warned believers against selling their last possessions to visit the monastery only to be told by a moody lama that his or her soul had “jumped out”(vyskochila) of the body. Another told of a lama who hit a grandmother on the head with a sausage(kolbasa) instead of touching her head in blessing.[11] By the late 1990s, Buryat Buddhism needed not only anew leader, but also entirely new grounds for legitimacy.Once elected, Aiusheev took all of the monasteries under his personal financial control and began rebuilding monasteries and stupas all over Buryatia.Even his most vocal opponents, in interviews with me, admitted that not only had he proved himself an excellent khoziaistvennik (executive manager) and prorab (construction site supervisor), but he was also merciless in fighting corruption and embezzlement. Aiusheev reformed the Board of Buddhists and changed its name to the Buddhist Traditional Sangha of Russia, which became legitimated as the main organization representing Buddhism in Russia. Subsequently, a “schism”(raskol) occurred in Buryat Buddhism, as several Buddhist communities declared their withdrawal from the Sangha and elected an alternative organ, which claimed the older name of Board of Buddhists. Lama Nimazhap Iliukhinov was then elected as the head of that Board, which conferred on him the title of Khambo Lama. Thus there appeared two different Khambo Lamas in Buryatia. In addition, in 1998 the Khambo Lama Aiusheev entered a protracted confrontation with Buryatia’s government (see Bernstein 2002 on the conflict over the so-called "Atlas of Tibetan Medicine"). Tibetan lamas began leaving Buryat monasteries and opening their own temples, attracting large local followings.

By 2002, when Itigelov was exhumed, the reputation of Aiusheev and the Sangha had been significantly compromised, and the future of Buryat Buddhism was increasingly uncertain. The discovery of Itigelov, however, radically reversed this situation. Why did his body produce such a dramatic difference in the Sangha’s status? Writing about the circulation of relics in medieval Europe, Patrick Geary notices that relics, which he refers to as “person-objects,”are high-prestige items that served as tools for creating community identity,status, and central ecclesiastical control. Smaller monasteries competed fiercely to get certain relics due to the enormous benefits they brought in terms of revenue, prestige, and pilgrimage traffic. The exchange of relics established bonds between givers and receivers, particularly relationships of dependency and subordination (Geary 1986). Below I demonstrate how Itigelov’s body began to redefine relations between the Sangha and other Buddhist organizations in Russia.

Beyond its legitimacy problems in Buryatia proper, the status of the Buddhist Traditional Sangha of Russia headed by Aiusheev has been highly contested throughout Russia. First, the Sangha includes mostly Buryats, but not all Buryat Buddhist communities. Second, other “ethnic” Buddhists prefer to have their own, independent sanghas . For example, Kalmyk and Tuvan Buddhists do not officially recognize the sovereignty of the Sangha. However, the Sangha’s possession of Itigelov’s body is subtly pushing these relationships from equality toward subordination.For a case in point, in2009 the president of Kalmykia, Kirsan Iliumzhinov, asked to “borrow” Itigelov’s body for the celebration of the four hundred years of Kalmykia’s “ voluntary annexation [prisoedinenie]” to Russia. Iliumzhinov argued that Kalmyk believers also wanted to worship Itigelov, but could not travel thousands of miles to Buryatiato do so. The Sangha “politely declined” this request, as reported in a Buryat newspaper article under the poignant title “Nevyezdnoi Itigelov”(nevyezdnoi, lit.“banned from travel,” a Soviet-era term often applied to dissidents denied foreign visas) (Makhachkeev 2009).[12] Furthermore, today the Sangha is the only Buddhist organization that has a direct relationship to the president of Russia’s administration. Aiusheev is the only Buddhist representative at the Interreligious Council of Russia in Moscow and a member of the Public Chamber of the Russian Federation. [13]That the Sangha now possesses Itigelovis an example of how such person-objects work to structure social relationships and hierarchies, in this case mediating rivalry between the two Sanghas.

While the Sangha’s deployment of Itigelov to boost its legitimacy is hotly debated in the republic, I do not wish to describe this phenomenon exclusively in strategic terms. Aiusheev’s devotion to Itigelov is no different from that of ordinary citizens. A monk close to the Khambo Lama told me that Soviet atheism dies hard even among lamas. But thanks to Itigelov, he contended,the Khambo Lama has become a believer, perhaps for the first time in his life. As he has gained piety he seems also to have gained confidence. “Ha,no one criticizes us anymore,” Aiusheev said to me with his usual mischievous smile, when I stopped by his residence at the Ivolginsk monastery one day. “They respect us. Or maybe they are afraid. Either way, no one dares anymore to say anything against us. And you know why? Because Itigelov won’t forgive them. ”Indeed, shortly after Itigelov was found and established,after many years of bitter conflict, the president of Buryatia had for the first time paid a visit to Ivolginsk monastery while Aiusheev paid his first visit to the Ministry of the Interior of Buryatia to reconcile with the “people in uniforms”(Makhachkeev 2004c).[14] Did Itigelov indeed come back so that everyone would make peace and live happily ever after? What was it about his body that turned it into such a powerful religio-political symbol? Quoting instances of a postsocialist “parade of corpses,” Verdery contends that while being central to the rewriting of history, dead-body politics can reveal shifts in the con-ceptions of time and space themselves (1999: 25 – 26). It is to this reordering and reconfiguring of Buryat spatial and temporal universes after Itigelov’s 2002 “coming” (prikhod) that I now turn.

BUDDHISM MARCHES NORTH: ITIGELOV’S PAST LIVES

In one of his field diaries, Buryat Buddhologist Bazar Baradiin writes about a particular prophesy that circulated in Lhasa around the turn of the twentieth century and spread to the Transbaikal through lamas returning from Lhasa and Tibetans who visited. The prophesy talked about the possible demise of Central Tibet (which Baradiin places in the context of the 1904 British invasion), with the center of Buddhism moving northwards to the monastery of Labrang in Amdo (Baradiin 1904). The contemporary popular rendering of this story goes as follows:

- Buddhism had already met its demise in Chinese Tibet.

- With the death of the current Dalai Lama and India being increasingly pressed by China, it will be marginalized in India, too.

- The center of Tibetan Buddhism is now shifting north to Mongolia, the only sovereign country which has Tibetan Buddhism as a state religion, and possibly, Buryatia, where Buddhism is also one of the official state religions.

While these geopolitical imaginaries have a role in reordering Buryat cosmologies of space, Buddhists hold the issue of transmission to be crucial to religion’s authenticity, and the fact of Itigelov’s return alone has not established the lineage. Tibetans, for example, claim that Buddhism taught in Tibet and by Tibetan lamas abroad could be traced backwards in an unbroken line to the eleventh century, when the founders of the major Tibetan schools traveled to India to receive the Dharma from the great Indian masters, who were themselves direct recipients of teachings that could be traced back to the Buddha himself (Lopez 1997: 24). Buryatia might now be the center, but how to restore the link between the undisputed Indian origin of Buddhism and its current Buryat version? Treasures, I suggest, are very effective agents for establishing such a link due to their ability to shorten the path between past and present, connect them, and thereby authorize the present. They provide focal points, where the painful recent past unfolds into a deeper, more glorious “golden age,” and they simultaneously announce the future byway of their present discovery. Treasures connect Buryatia to India by linking local lama bodies to important Indian personalities.

Itigelov’s body shares important characteristics with classically known “treasure” objects. First, it serves as the physical link to the past while being oriented toward the future. This is perhaps true for all relics in general. More crucially,however, and similarly to the other treasure objects, whose concealers designed them to benefit the future generations during times of hardship, Itigelov is believed to have engineered his own burial and exhumation during a particular time after his death, thus being a kind of self-concealing treasure. Being one link in the endless “rosary of bodies,” Itigelov’s body not only stands for the authenticity of Buddhist transmission and continuity with older religious forms, but also embodies multiple temporal regimes. He is simultaneously himself and a reincarnation of the first Khambo Lama Damba-Darzha Zaiaev(1711 – 1776), credited with introducing Buddhism into Buryatia. Itigelov, as one Buryat told me, is “two in one” (dva v odnom).

Drawing on Gregory Schopen’s work, Buddhologist John Strong notes that Buddhist relics are “alive,” since they can “own property, perform miracles,inspire devotees” and are “filled with various Buddha qualities” (Schopen1990; Strong 2004: 4). Unlike other scholars of Buddhism who treated Buddhist relics as “indexical icons” and “sedimentation of charisma” (Tambiah1984: 5, 335ff), or as “memory sites” and the “ultimate embodiment of a commemorative consciousness” (Hallisey in Strong 2004: 4), Strong (who concentrates on the relics of the historical Buddha) suggests that instead of focusing on the “presence” or “absence” of the Buddha in the relics, relics should be viewed as “expressions and extensions of the Buddha’s biographical process” (see 2004: 4 – 5, for Strong’s comprehensive overview of the scholarship on Buddhist relics). Biographies of Buddhist saints do not start with their births and do not end with their deaths; they include the masters’ previous lives (incarnations) and posthumous existences (of which relics are only one aspect). Morethan just being “two in one,” Itigelov attests to the capacities of incarnate bodies to embody multiple temporalities. Worshippers who come to touch Iti-gelov are touching much more than his present body. His relics embody ahistory that is longer than his life, reaching back to the time of Zaiaev over two centuries ago. Itigelov’s body, however, does not merely evoke the past.Since he is believed by many to be “alive” and in meditation, he embodies the “slow” time of the present, unaffected by the normal rhythms of everyday life. Like other treasures, he also indicates the imagined future temporality of Buryatia’s permanent re-entry onto the Buddhist scene. And if, as Strong suggests, relics are extensions of the biographical process, in this case it did not take long for such biography to materialize, again in a mysterious way.

In 2005, a five-page text attributed to Itigelov was discovered among the thousands of manuscripts in Ivolginsk monastery. No one was able to tell me where this text had been before, and the consensus was that it had intentionally revealed itself through the agency of Itigelov. In it, he described how in one of his previous lives as Zaiaev, he had offered gifts to the Dalai Lamas and Panchen Lamas who passed to him the information about his past lives. The document provided a list of what are interpreted as his former lives, which include five Indian, five Tibetan, and two Buryat incarnations.Upon discovery of this text, the Khambo Lama declared that this piece “largely explains the subsequent history of Buryat Buddhism” (Makhachkeev2005). After the discovery, the Khambo Lama, in a provocative interview, mini-mized the role of Tibet:

- Journalist: Considering the complex situation in Tibet and uncertainty regarding the future reincarnation and the institution of the Dalai Lamas on the whole, can we definitely say that there is a decline in the influence of Tibetan religious leaders on the minds of Buryat believers?

- Khambo Lama: Buryat Buddhism has been quite self-sufficient during several centuries and reached incredible heights. The example of the Khambo Lama Itigelov, as well as our other great lamas, speaks for itself. One should not feel like a second-rate person.

- Journalist: Venerable Khambo Lama, do you mean that it is a manifestation of some kind of cultural or religious colonialism when one prefers imported ideals over his native ones? But, as we know, Buddhism has reached Buryatia from the south — through Tibet and Mongolia?

- Khambo Lama: Buryats received Buddhism from Damba-Darzha Zaiaev, who, in turn, received it in his first incarnation from Buddha Kasyapa, and in his second incarnation — from Buddha Sakyamuni! Remember this (Makhachkeev 2008a).[15]

Many people took this statement to mean that the Khambo Lama was denying the fact of Buddhism’s historical transmission from Tibet to Mongolia to Buryatia. [16] When I visited the Khambo Lama in 2008, I asked him to clarify this statement. He offered me the following interpretation:

- One peculiarity of Buryat Buddhism is that we took it ourselves. Russia was baptized by Prince Vladimir. Mongols accepted Buddhism on the orders of Khubilai and Altan Khan. It was all coming from above. In Tibet they had Padmasambhava and missionaries-pundits from India. The same in China. We, Buryats, received Buddhism thanks to the son of our people, Zaiaev, who studied in Tibet despite the will of his parents. The phenomenon of Zaiaev allowed for the spread of Buddhism after his return from Tibet. Subsequently, Buryat Buddhism received autocephality and its own institution of Khambo Lamas, because when Catherine the Great met Zaiaev, she under-stood that he was a great man.[17]

Almost three centuries after Zaiaev’s trip to Tibet, his reincarnation as Itigelov, who never traveled abroad, is becoming a sign that long-distance authorizationsmay soon be considered obsolete. One no longer needs to go to distant lands to become a great master, since by the early twentieth century Buryat Buddhismhad already reached its “golden age.” “Why do we Buryats always try to bow infront of foreigners? Look at Itigelov — he never went anywhere, ”the KhamboLama likes to say.

Itigelov’s exhumation set in motion the search for other treasures. Not only were other Khambo Lamas unearthed in an attempt to discover other incorruptible bodies, but also all over Buryatia ritual objects, old scriptures, and other attributes of pre-Soviet Buddhist life started bursting from the ground.

RUINS AND TREASURES AS GEOMANTIC AGENTS

An important place where treasures are often found is the ruins of former monasteries, which assumed special geomantic significance during the postsocialist period. They literally serve as portals into worlds past. One of the first major finds after Itigelov were 450 identical Buddha statues buried in the vicinity of the ruins of Aninsk monastery. Three of the statues were found under a stone slab in August 2002, about a month before Itigelov was exhumed. By November 2002, fifty more were found, and by February 2004 the number had reached 203. After a religious ceremony was held devoted to the Buddhist New Year, about 150 more statues were unearthed at a spot where they were not previously seen (see image 3). In fact, it is said that in the late 1990s metropolitan archeologists had looked for treasures at the same spot but had found nothing. “Before starting the dig, we conducted a ceremony and asked themain protector of the Aninsk monastery, Gombo [Skt. Mahakala)], for blessings and guidance,” said Legsok Lama, the head of the dig. “It is not we who found these Buddhas, they revealed themselves to us. It is not a coincidence that they revealed themselves to the world now, when Khambo Lama Itigelov arrived! Itigelov studied and lived in the Aninsk monastery for twenty years. We see a deep mystical connection between the advent of the incorruptible body and the appearance of the Buddhas” (Makhachkeev 2004a) (see image 4). It is said that one thousand Buddhas were buried here, and a search for the remaining 550 statues continues. While rumors of a rich collector having visited the monastery some years ago provoked much anxiety that the rest might be long gone, those 450 Buddhas at the Aninsk monastery promoted a flow of pilgrims, donations, and volunteers whose efforts eventually enabled its full restoration.

The Buddhas of Aninsk — the first widely publicized treasure to appear after Itigelov — seem to have set other treasures in motion. During the initial cleaning of the ruins of the Dzhida monastery, destroyed in the 1930s, an abandoned well covered with earth was discovered. The lamas decided to clear it in order to have access to water and discovered a colony of frogs in the state of anabiosis, with many rusty ritual Buddhist implements buried underneath. The frogs were taken away and eventually came to life, which was taken asan auspicious sign for the monastery’s full restoration.[18]

These finds reveal a particular Buddhist object-ideology, wherein objects are imbued with partial personhood and agency of past lamas (see Gell’s “distributed personhood,”1998: 21), as in the case of Aninsk treasures, where the statues were believed to be linked to Itigelov’s intentions. In this complex system of social relations between humans, objects, and enlightened beings,monasteries themselves are invested with partial personhood. They are viewed as indices of past lamas’ agency, and often serve as channels for the discovery of treasures.

The agency of ruins is not always viewed as benevolent, however. Abandoned monastery ruins are viewed as especially dangerous places that are to be treated with extreme caution and respect. Take, for example, the case of the Alar monastery, built in 1815 in the region of Ust’-Orda. Although it had been completely razed in the 1930s, its former territory has been twice reported to be the site of mysterious and sometimes tragic events. Once someone tried to dig a vault there but lost his crowbar when it was “swallowed” by the earth. In a second occurrence, a large poplar tree was toppled by strong wind. One man, despite warnings, decided to take it home and chopped it up for firewood. The next day he got into a motorcycle accident that left him handicapped (Sanzhi-khaeva 2004).

What makes these ruins places of geomantic significance? After the Soviet period, with all thirty-six monasteries destroyed (and two rebuilt after World War II), ruins became an integral part of the Buryat landscape (see image 5). Since pre-revolutionary monasteries were almost never built in towns or villages but rather at some distance from them, their ruins often appear to be blended with, and are perceived as a part of the natural landscape. A rich Western tradition of thinking about ruins, however, prompts one to reconsider ruins as a particular kind of place where multiple historical layers overlap. Ruins have been perceived as places where “history is physically merged into the setting,” which in turn casts history as a process of “irresistible decay.” Ruins thus become an allegory of history itself (Benjamin 1998:177 – 78). Other scholars interpreted ruins as focal points of remembrance that possess “multiple temporalities” (Edensor 2005), as the material debris that enable the persistence of imperial formations (Stoler 2008: 194), or, as in the case of abandoned churches in various states of disrepair in Soviet urban contexts, as ways to both encode political change and undermine the socialist master plot of progress (Schönle 2006: 665 – 66). Buryat monastic ruins became dramatic instances of places that condense temporalities, with crucial links not only to the past but also to the future, through the agency of treasures that “reveal” themselves in their midst.

Unlike some of the more static modern ruins that continue to fascinate cultural theorists, the trajectory of Buryat monastery ruins, as objects cast off by socialist modernity, is undergoing a dramatic turn. As they are gradually being turned into replicas of their former selves, what is taking place is a certain reconfiguration of not only space but also time, expressed in the virtual excision of time periods, visions of cyclical time through incarnations and reincarnations, and the “deepening” of the timeline, which changes the perception of one’s place in time and history. Many monasteries are restored to be exact copies of the pre-revolutionary structures, while others are built in a different style that nonetheless always displays linkages to specific historical occurrences. Itigelov’s new palace was built based on a photograph of a temple found in the Museum of the History of Buryatia. That former temple, a part of the Iangazhinsk monastery destroyed in the 1930s, is said to have been built by Itigelov himself when he served as an abbot at Iangazhinsk. Ianzhima Vasil’eva is the spokesperson for the Institute of Itigelov, a non-profit organization devoted to promoting the heritage of the lama, and is said to be his grand-niece. She emphasized that the new structure was not just a temple but a palace, because a palace was also built for the first Khambo Lama Zaiaev. “This way,the tradition is observed, and Khambo Lama Itigelov is moving back into his palace. As you understand, the 12th Khambo Lama Itigelov is no one else but the Khambo Lama Zaiaev in his twelfth incarnation!”(Basaev 2008, my italics) (see image 6). The number twelve here presumably refers to the document of Itigelov’s past lives, which states that he had five Indian and five Tibetan incarnations, with 11th being his first Buryat incarnation as Zaiaev. She deploys the deepest sense of “Buryat” history, starting with ancient India, and thus time, space, and one’s place in both time and space are being reconfigured. Unlike Tibet, in Buryatia the institution of the incarnate lama — with successive generations of great teachers identified while they were children — was never established. However, some lamas have been posthumously proclaimed to be embodiments of previous masters, as in the case of Itigelov being proclaimed an incarnation of the first Khambo Lama Zaiaev. Manyin Buryatia today wonder whether Aiusheev himself might eventually be pro-claimed an incarnation of Itigelov. This would not only link Aiusheev to the beginnings of Buddhism in Buryatia, but would also open the doors to conceiving origins in multiple ways: from the birth of the Buddha in the fifth century BC, to the renaissance of Buddhism in Tibet in the eleventh century, to the return of Zaiaev from Tibet in the mid-eighteenth century.

So far as the reordering of space, a key function of both treasures and ruins is that they allow for the production of the new sacred geographies while also preserving a necessary continuity with the past. Buddhist sacred places never appear on neutral lands. In twelfth-century Tibet, sacred mountains were redefined as tantric Buddhist pilgrimage sites through the process of “mandalization,” whereby mandalas were imposed on the landscape as the organizing principle (Huber 1999). Similarly, Tibetan historiographers have interpreted the placements of early temples in Tibet as having “nailed” to the ground the “supine demoness,” who inhabited this land prior to the advent of Buddhism, at various parts of her body (Davidson 2005: 87; Gyatso 1987). In Buryatia, both treasures and ruins serve as geomantic agents, indexing qualities of the land-scape into which Buddhism re-inscribes itself. While treasures found at the ruins of former monasteries allow for the restoration of these religious structures to their former glory, treasures found in the landscape with the dead bodies of famous personalities are a necessary element for the expansion of Buddhism into new territories. While the treasures discussed up to this point were used to re-consecrate former sacred spots, in what follows I give an example of how treasures are used for the development of new sacred geographies to demonstrate that the post-Soviet revival of Buddhism goes beyond a simple restoration of the past. A treasure found in a remote Barguzin forest, paired with a powerful dead body, set off a chain of magical events and eventually transformed this rugged region, still known for its powerful shamans, into arguably the second most important focal point on the map of the newest Buddhist sacred geography, rivaled only by the current location of Itigelov (see image 7).

IANZHIMA REVEALS HERSELF

The Barguzin Valley is an attractive region with dense taiga forests, snow-capped mountains, and crystal-clear blue lakes. It received Buddhism about a hundred years later than other Buryat regions, after a famous lama named Nimalain won a magical contest with shamans. Nonetheless, up to the destruction of Buddhism in the 1930s, shamanism remained quite strong in this region.During the Soviet period, in the absence of organized religion, shamanic traditions grew still stronger. They remain so today: whenever a problem arises,local custom requires people to visit a shaman first before heading to the monastery. It is shamans who are in charge of the preliminary ritual of “opening the road,” without which any services conducted by the lamas are deemed ineffective. The Khambo Lama, the most outspoken opponent of shamans, appeared to be less than pleased with this situation. Moreover, during the 1990s, Kurumkan, the only Buddhist monastery in the valley, served as a retreat base for the popular Tibetan teacher Geshe Jampa Tinley, and this made this region a sort of Mecca for esoteric devotees of all stripes, many of whom were metropolitan Russians. In other words, by 2005 the Barguzin Valley stood out like a sore thumb on the otherwise triumphant map of the Sangha’s consolidation of power. It was at this time that the Sangha lamas, headed by the Khambo Lama himself, determined to rectify this situation and conducted an arduous journey to Barguzin to look for an appropriate place to build a new monastery.

Construction of new Buddhist monasteries is a highly ritualized affair that involves a number of complex procedures leading to the determination of the proper site. Steps include astrological divinations and “taking possession” of the land, which is often referred to as “taming” (see Gardner 2006). Therefore,upon arrival in the valley the Khambo Lama immediately inquired as to whether there were any auspicious places or events in this region. Locals recalled that in 1996 Buryat hunters had in the pine forest above the village of Iarikto found a tsa tsa, a miniature Buddhist votive clay-relief, pyramid-shaped figurine of one thousand Buddhas of the kind used in large numbers to fill up the inside of a stupa. Aiusheev with his lamas immediately headed to the spot and searched for more treasures, but could find nothing. What then happened is already a canonical story: Tired from these unsuccessful searches, Khambo Lama sat down under a tree and entered a deep state of mediation, reciting the mantra of Itigelov. When he opened his eyes, he saw clearly the face of a deity that appeared on a large stone right in front of him.This was a self-arisen image, common in the Tibetan Buddhist and Hindu traditions, an image considered to be of non-human origin. The Khambo Lama pronounced in Buryat, “Endemnai Burkhan suuzha baina!” (Oh! A Buddhais sitting here!). His lamas and accompanying locals now also saw what he saw — a big stone covered with multi-colored mineral stains, which could vaguely resemble a deity if one tried hard to fill in the blanks. Later, iconographers were invited to determine which deity this was, and it was pronounced to be the goddess Ianzhima (Skt. Saraswati, Tib. Yangchenma) since she appeared to hold a lute and to stand with a raised leg, a characteristic pose recognizable from her iconography. A colorful booklet published by the Sangha soon after this discovery and sold at the site contextualized its meaning:

- Everyone understood then that the ritual pyramid-shaped figurine was left here by the great son of the Barguzin Valley, Tsyden Sodoev [Soodoi Lama), who was meditating in this place.… Barguzin Buryats believe that the treasures from the Barguzin monastery are buried around this spot.… Khambo Lama often says,

“There are no coincidences in Buddhism.” Now we understand that the goddess of Art and Wisdom Ianzhima was the main meditational deity of Soodoi Lama, and it is not a coincidence that she revealed herself to the Khambo Lama Damba Aiusheev himself (Budaeva 2006: 5).

The evocation of the famous lama-prophet of the region, Soodoi Lama (1846 – 1916), who is locally believed to be an incarnation of the famous Indian Buddhist master Nagarjuna, and his promotion to the level of a national saint, are key to the processes of space-time making and religious authorization considered in this article. A rare cosmopolitan in his times, Soodoi Lama was a prophet, a person with special powers to access a range of temporalities not only through his ability to read the future, but also, and perhaps most crucially, due to his being considered an incarnate lama (see image 8). Like Itigelov, Soodoi Lama’s persona compresses different temporal and spatial regimes. Through the initial treasure find, the tsa tsa pyramid, believed to have been left there by Soodoi Lama himself, the unique and miraculous event of a self-arisen Ianzhima is now firmly linked with his ineffable presence: the lama’s body is thought to be buried in the vicinity while his “spirit has been flying invisibly over the valley for 160 years” (ibid.: 6).[19] Thus powerful dead bodies of pre-Soviet Buryat personalities not only help establish new post-socialist religious cults and practices, but also are instrumental in creating new timelines and alternative histories. Soodoi Lama’s past lives as Nagarjuna allow once again for the minimizing of Tibet’s role in the Buryat Buddhist lineage by establishing a second line of transmission directly from India, in addition to Itigelov’s.

While the discovery of Itigelov reordered Buryat cosmologies of time, the discovery of Ianzhima turned out to be crucial for the reordering of space,since both events are locally seen as proof of Buryatia’s newly acquired status as the emerging center of the Buddhist world. Lamas invoke the fact that in Hindu mythology Saraswati was also a sacred river, worshiped as much as the Ganges. However, due to the coming of “dark times” the river dis-appeared underground and was expected to come back at a better time. The coming of Saraswati-Ianzhima to Buryatia is regarded as a sign that the locus of the authentic spirituality had definitively moved northwards from its Indian origins, once again reconfiguring the notions of religious centers and peripheries. In an interesting twist, the goddess of Art and Wisdom soon became known to locals as the patron of motherhood, since Barguzin villagers have interpreted her lute as a big round stomach signifying pregnancy. The supporting fact that the goddess was facing the village of Elysun, which reportedly boasted the highest number of “mother-heroines” in the former Soviet Union,was soon buttressed by news of women being successfully treated for infertility after visiting the site. Dolls and baby clothes were soon heaped around the site,while stories about reproductively challenged women getting pregnant with the help of Ianzhima began to circulate in the local and national press. The redefinition of this goddess, previously obscure for Buryats, as a fertility-granting deity secured the popular appeal of this newly established pilgrimage site (see images9 and 10).

As in the other cases I have presented here, this major find spearheaded the appearance of other treasures across the region. In 2008, more than one thou-sand ritual Buddhist objects, as well Russian imperial coins, musical instruments, and, curiously, a tsarist army sword (which had likely been laid as a foundation of a tantric temple of a former monastery) were unearthed. Newspapers reported that the findings were accompanied by “mystical occurrences,” such as sudden strong showers and the chimes of bells coming from underground (Makhachkeev 2008b). Popular rumors continue that Ianzhima is usually accompanied by her sister Norzhima, the goddess of Wealth, who should “self-arise” (proiavit’sia) any day now. Most importantly, a new monastery was built near Ianzhima. The Sangha named it the official legal successor to the former Barguzin monastery, whereas the Kurumkan monastery (which in fact was built at the exact site of the former monastery) lost its privileges as the representative of the Buryat Buddhist “golden age.” An official prayer service to Ianzhima marking the day of her manifestation in early May was established and is now held annually by the Khambo Lama and by abbots of all Buryat monasteries,who personally visit Barguzin on this date. By the time of my visit there in 2008, the spot was a well-established pilgrimage site, complete with prodigious local mythology, a new monastery, a pilgrim hotel, and a traditional restaurant. It received thousands of visitors from across Russia and abroad.

The discovery of Ianzhima also casts the perception of the Khambo Lama in an entirely new light. No longer simply a good khoziaistvennik, or manager, Aiusheev emerges as a charismatic religious specialist with geomantic powers like those of a Tibetan treasure revealer, a person who is able to read the landscape and make the unseen visible. As in many other cases, the revival of Buddhism in Barguzin was also accompanied by

- the discovery of a treasure;

- interpreted as being linked to the dead body of a famous saint believed to be buriedsomewhere around;

- followed by magical events (appearance of a self-arisen goddess);

- all of which gave rise to new sacred geographies, historiographies, and cosmologiesof both time and space;

- all of the above strengthened the claims to cultural sovereignty.

CONCLUSION

The “treasures” considered in this article reveal a particular Buddhist object-ideology: the objects are approached as potential expressions of past intentions, of previous lamas. The question of materiality and durability seems significant because the durable qualities of what is left behind or hidden are what make them available. Once discovered, objects — relics, self-arisen images, and ritual implements — become sensible (can be sensed) and visible. In that regard, they are different from the private visions of specialists who see what others cannot, although religious specialists are required to make the initial discovery of an object. It is this materiality that makes them ideal agents for creating new discourses of time and space (because they can move visibly through both), agents that become productive arenas for religio-political struggles.

Treasures reveal an interesting dialectic between continuity and rupture.Analyzing the discourses around treasure discovery in Greece, Charles Stewart notes that while treasures are extremely effective in providing continuity with the past, they themselves are paradoxically products of “rupture”: of ethnic cleansings, wars, and invasions (2003: 489). Indeed, in Buryatia, there would have been no treasures if not for the violence of the Russian Revolution and subsequent secularization campaigns that forced believers to inter particularly important ritual objects to prevent their being captured by the Militant Godless[20] and either destroyed or placed in the Museum of Atheism.[21] There was another reason, however, to bury the treasures in this particular context that stems specifically from the Buryat Buddhist view of objects’ personhood and agency. Buryats believe that Buddhist objects require and even demand constant use, but only by qualified specialists. Thus, Buddhist texts must be read — should one have sacred books at home that are not regularly read by a visiting lama, or ritual implements that are not used in ritual, such objects may become dangerous for their keepers. Since most Buddhist books in Buryatia were written in Tibetan, ordinary believers were not usually able to read them. As more lamas were purged and knowledge about the use of the ritual objects was gradually being lost, many believers disposed of their Buddhist objects; they buried them deep in the forest, or placed them near the sources of streams, which are locally considered to be places of power. Thus one was compelled to get rid of sacred objects out of fear of not only the Soviet authorities but also the wrath of the objects themselves. Now, with many qualified religious specialists appearing in Buryatia, it would make sense that the objects are eagerly coming back.

Since it is the powerful dead who are believed to give treasures efficacy, in Buryatia necropolitics has, as in other postsocialist contexts, been crucial in reordering time and space, revising the past, and reestablishing moral authority. Exemplary dead bodies have re-consecrated the post-Soviet Buryat landscape,setting in motion the appearance of treasure objects, which are believed to have distributed agency and intentionality through their association with past great masters. Other events around dead bodies, such as miraculous “self-arisen” images and treasure objects at the sites of ruins, have been interpreted as a proof of Buryatia’s claim to be the up-and-coming center of the Buddhist world. Treasures lengthen Buryat Buddhist history, linking Buryatia to the beginnings of Buddhism in ancient India while giving material support to the local notion that the Buddhist center of gravity has definitively shifted north-ward. These renovated time-space cosmologies are important not only as ethnographic documentations of changing Buryat universes of meaning, but as key political claims in their assertions of cultural sovereignty both within the Russian Federation and in the transnational Tibetan Buddhist world.

By subverting established hierarchies of centers and peripheries, Buryat Buddhists are rebuilding their own legitimacy, staking a place for themselvesin the global religious marketplace. On a broader scale, such processes contrib-ute to the ongoing reorganization of world religions caused by the end of social-ism, in effect by re-centering world Buddhism. The end of socialism introducednew players on the stage of world religions, as faiths that had been suppressedfor most of the twentieth century entered the now global spiritual marketplace.At the same time, formerly socialist territories attracted the attention of other religions previously excluded from proselytizing there. In this context, the “treasure” objects considered here crucially reconfigure not only Buryat, but also the global Buddhist landscape.

Footnotes

- ↑ Dashi-Dorzho Itigelov (1852 – 1927) was the Khambo Lama from 1911 to 1917.“Pandito Khambo Lama”is the supreme Buddhist ecclesiastical title in the Russian Federation. Up to the present there have been twenty-three Khambo Lamas, with the current Khambo Lama Damba Aiusheev being the twenty-fourth. Buddhism, traditionally practiced in the regions of Buryatia, Kalmykia, and Tuva, is one of the four official state religions in Russia, along with Russian Ortho-doxy, Islam, and Judaism.

- ↑ Some sources report that Itigelov was exhumed again in 1972, his body still intact, and again reburied (Badueva 2006).

- ↑ Besides cutting-edge science,a major influence upon the emergent cult of Leninin early Soviet Russia was the Russian Orthodox tradition of relics veneration (Tumarkin 1997: 4 – 6).

- ↑ After 1992, the Dalai Lama was repeatedly refused permission to visit Buryatia, while he was granted a visa for a brief visit to Kalmykia in 2004.

- ↑ See Makley (2007: 96 – 97) for the application of this notion in another Tibetan Buddhist context.

- ↑ This observation is inspired by Katherine Verdery’s analysis of “recentering” of world Christianity. In her examination of the “restless bones” of the Transylvanian Bishop Inochentie Micu, she demonstrates the manifold ways in which these religious relics on the move contributed to shifting the power balance between Catholic and Eastern Christian churches in Europe (1999: 55 – 95).

- ↑ Gyatso notes that, with time, the reasons for concealment had changed: rather than trying to simply protect the texts from present adverse conditions, the concealers of treasures refocused their concern on the future times of hardship, when these teachings would be particularly needed(1996: 152).

- ↑ See also Terrone (2008) for a more recent account of contemporary treasure revealers in Tibet.

- ↑ Here it must be noted that the Sangha has no intention to imitate strategies employed by the Nyingma school, and they do not make this connection. My point is that Buryats found a way to produce new legitimate sacred objects and sites in a structurally similar context of religious revival, as new strategies of authentication are being developed.

- ↑ Another interesting parallel is that the phenomenon of Tibetan treasures came into full flower after the demise of Buddhism in India. That is, it was no longer possible to go to the source to retrieve the Dharma, so the foreign source was discovered “at home,” much like Buryats finding treasures in Buryatia after the possibility of going to Tibet was lost. Also, just as Indian masters went to Tibet to escape Muslim persecution, so, too, Tibetan lamas are “escaping” to Buryatia.

- ↑ The touching of the head is a standard Buddhist blessing in classical Buddhist contexts deter-mined by the rank of the believer. In pre-Chinese Tibet, while lamas touched high-rank believers’ heads with both hands, less important people received a blessing with one hand or a finger, and they touched those of the lowest status with a short stick with colored ribbons.

- ↑ Aleksandr Makhachkeev is a journalist for the local weekly newspaper Inform-polis who often covers Buddhist issues in the republic.

- ↑ The Interreligious Council, an important organization for inter-religious dialogue created in1998, includes leaders of Russia’s four traditional religions. It works to develop relations between the government, religious groups, and society.

- ↑ The rapprochement started in 2004, when, for the first time since 1998, high-ranking government officials visited the Ivolginsk monastery, presumably due to their interest in Itigelov (Makhachkeev 2004b). During the visit to the Ministry of the Interior, Minister Mikhail Tsukruk told Khambo Lama that his young men who serve in Chechnya always have Itigelov’s picture on the windscreens of their Ural military trucks. “The Chechens ask them: ‘Who is it?’ And our guys reply,‘With him, no landmine can hurt us’”(Makhachkeev 2004c)

- ↑ Kasyapa is known as the Buddha who preceded Buddha Sakyamuni, who is known as the “historical Buddha.”

- ↑ Some advanced Buddhist adepts maintain that Aiusheev’s take on the role of Itigelov’s past lives in establishing the authenticity of Buryat Buddhism is egregiously ill-informed, noting that Tibetan Buddhism holds authentic transmission in this life to be crucial. That is why, they point out, it is so important that all Tibetan tulkus receive all of the teachings again , despite the fact that they might have already received them countless times in their previous incarnations (interview,Dharamsala, India, 2008).

- ↑ Interview, Ivolginsk, Buryatia, 2008. Zaiaev studied in Drepung Gomang monastery in Tibet in 1727 – 1732 and was granted the title of the Khambo Lama by the Russian empress in 1764.

- ↑ Nikolai Tsyrempilov, personal communication, Sept. 2008.

- ↑ See Makley (2007: 33) on establishing certain regions as “fields of action” of specific incarnate lamas.

- ↑ “The League of the Militant Godless” was a mass volunteer anti-religious organization started in the Soviet Union in the 1920s.

- ↑ During the Soviet times, many objects from the destroyed churches, mosques, and Buddhist temples have been exposed as part of anti-religious exhibitions at the Museum of the History of Religion and Atheism (Muzei istorii religii i ateizma) housed in the Kazan Cathedral in St.Petersburg. In Buryatia, Odigitrievsky Cathedral in Ulan-ude has been used as a museum of atheism.

ARTICLE REFERENCES

- Badueva, Nana. 2006. Chudesnaia taina roda Ulzy [Miraculous mystery of the Ulzyclan]. Inform-Polis, 8 Nov.: 8.

- Baradiin, B. B. 1904. Dnevnik Badzara Baradiina, komandirovannogo Russkim Komitetom dlia izuchenia Srednei i Vostochnoi Azii v Zabaikal’e [Diary of Badzar Baradiin, sent to the Transbaikal by the Russian Commitee for the Study of Central and Eastern Asia]. St. Petersburg Orientalist Archive, F. 87, D. 26. St. Petersburg.

- Basaev, Sergei. 2008. Dvorets dlia netlennogo tela [Palace for the incorruptible body). Inform-Polis, 2 Nov. At: http://www.infpol.ru/newspaper/number.php?ELEMENT_ ID=13237 (accessed May 7, 2009).

- Benjamin, Walter. 1998. The Origin of the German Tragic Drama. John Osborne, trans.London: Verso.

- Bernstein, Anya. 2002. Buddhist Revival in Buryatia: Recent Perspectives. Mongolian Studies 25: 2 – 11.

- Buck-Morss, Susan. 2000. Dreamworld and Catastrophe: The Passing of Mass Utopiain East and West. Cambridge: MIT Press.

- Budaeva, L. 2006. Boginia Yanzhima: Fotoal’bom [[[Goddess]] Ianzhima: a photo album]. Ulan-Ude: NovaPrint.

- Davidson, Ronald M. 2005. Tibetan Renaissance: Tantric Buddhism in the Rebirth of Tibetan Culture. New York: Columbia University Press.

- Edensor, Tim. 2005. Industrial Ruins: Space, Aesthetics, and Materiality. New York: Berg.

- Gal, Susan. 1991. Bartók’s Funeral: Representations of Europe in Hungarian Political Rhetoric. American Ethnologist 18, 3: 440 – 58.

- Gardner, Alexander. 2006. The Sa Chog: Violence and Veneration in a TibetanSoil Ritual. Études Mongoles et Sibériennes, Centrasiatiques et Tibétaines 36 – 37:283 – 323.

- Geary, Patrick. 1986. Sacred Commodities: The Circulation of Medieval Relics. In A.Appadurai ed., The Social Life of Things: Commodities in Cultural Perspective. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 169 – 95.

- Gell, Alfred. 1998. Art and Agency. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Germano, David. 1998. Remembering the Dismembered Body of Tibet: Contemporary Tibetan Visionary Movements in the People’s Republic of China. In, M. C. Goldstein and M. T. Kapstein, eds.,Buddhism in Contemporary Tibet: Religious Revival and Cultural Identity. Berkeley: University of California Press, 53 – 95.

- Gyatso, Janet. 1987. Down with the Demoness: Reflections on the Feminine Ground in Tibet.Tibet Journal 12: 38 – 53.

- Gyatso, Janet. 1993. The Logic of Legitimation in the Tibetan Treasure Tradition. History of Religions 33, 2: 97 – 133.

- Gyatso, Janet. 1996. Drawn from the Tibetan Treasury: The gTer ma Literature. In J. I.Cabezón and R. R. Jackson, eds., Tibetan Literature: Studies in Genre. New York:Snow Lion, 147 – 70.

- Hamayon, Roberte N. 2002. Emblem of Minority, Substitute for Sovereignty: The Case of Buryatia. Diogenes 49, 2: 16 – 21.

- Huber, Toni. 1999. The Cult of Pure Crystal Mountain: Popular Pilgrimage and Visionary Landscape in Southeast Tibet. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Kantorowicz, Ernst. 1957. The King's Two Bodies: A Study in Mediaeval Political Theology. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Lopez, Donald S. 1997. Introduction. In D. S. Lopez, ed., Religions of Tibet in Practice. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 3 – 39.

- Makhachkeev, Aleksandr. 2004a. Buddiiskie sokrovishcha v Khorinske [[[Buddhist]] treas-ures in Khorinsk]. InformPolis, 3 Mar. At: http://www.infpol.ru/newspaper/number.php?ELEMENT_ID=2864 (accessed 7 May 2009).

- Makhachkeev, Aleksandr. 2004b. Prezident i Khambo Lama poshli na sblizhenie[[[President]] and Khambo Lama started the rapprochement].Inform-Polis, 22Dec.: 6.

- Makhachkeev, Aleksandr. 2004c. MVD i lamy: konflikt ischerpan [MVD and lamas:conflict is over].Inform-Polis, 29 Dec. At: http://www.infpol.ru/newspaper/number.php?ELEMENT_ID=3415 (accessed 7 May 2009).

- Makhachkeev, Aleksandr. 2005. Naidena unikal’naia kniga Itigelova [A unique book byItigelov has been found].Inform-Polis, 6 Apr.: 5.

- Makhachkeev, Aleksandr. 2008a. Voprosy k ierarchu [Questions to the hierarch].MK v Buriatii, 26 Mar. At: http://mk.burnet.ru/index.php?option=com_content&task=view&id=1663&Itemid=12, (accessed 7 May 2009).

- Makhachkeev, Aleksandr. 2008b. Buddy i sablia [The buddhas and a sword].MK v Buriatii, 3 Dec. At: http://mk.burnet.ru/index.php?option=com_content&task=view&id=2348&Itemid=12#comment-847 (accessed 9 May 2009).

- Makhachkeev, Aleksandr. 2009. Nevyezdnoi Itigelov [Itigelov’s travel banned].Inform- Polis, 3 June. At: http://www.infpol.ru/news/number.php?dd=1243999800&ELE-MENT_ID=20100&PAGEN_2=2 (accessed 4 June 2009).