The Shambhala warrior

Trungpa had told one of his pupils that during deep meditation he was able to espy Shambhala. He also said he had obtained the teachings for the “Shambhala training” directly from the kingdom.

The program consists of five levels:

The art of being human

Birth of the warrior

Warrior in the world

Awakened heart

Open sky - The big bang

Anyone who had completed all the stages was considered a perfect “Shambhala warrior”. As a spiritual hero he is freed from the repulsiveness which the military trade otherwise implies.

His characteristics are kindness, an open heart, dignity, elegance, precision, modesty, attentiveness, fearlessness, equanimity, concentration, and confidence of victory. To be a warrior, one of Trungpa’s pupils writes, irrespective of whether as a man or a woman, means to live honestly, also in regard to fear, doubt, depression, and aggression which comes from outside. To be a warrior does not mean to conduct wars. Rather, to be a warrior means to have the courage to completely fathom oneself (Hayward, 1997, p. 11).

This subjectification of the warrior ethos brings with it that the weapons employed first of all represent purely psycho-physical states: controlled breathing, the strict stance, walking upright, clear sight.

The first basic demand of the training is, as in every tantric practice, a state of "egolessness”. This is of great importance in the Shambhala teachings, writes Trungpa. It is impossible to be a warrior if you have not experienced egolessness. Without egolessness, your consciousness is always filled with your ego, your personal plans and intentions (Hayward, 1997, p. 247).

Hence the individual ego is not changed through the exercises, rather the pupil tries solely to create an inner emptiness. Through this he allows himself to be transformed into a vessel into which the cult figures of the Tibetan pantheon can flow. According to Trungpa these are called dralas. Translated literally, that means “to climb out over the enemy” or in an further sense, energy, line of force, or “gods”.

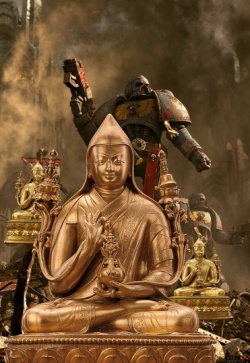

The “empty” pupils thus become occupied by tantric deities. As potential “warriors” they naturally attract all possible forms of eager to fight dharmapalas (tutelary gods). Thus a wrathful Tibetan “protector of the faith” steps in to replace the sadhaka and his previous western identity. This personal transformation takes place through a ritual which in Trungpa’s Shambhala tradition is known as “calling the gods”.

The supernatural beings are summoned with spells and burning incense. When the thick, sweet-smelling white smoke ascends, the pupils sing a long incantation, which summons the dralas. At the end of the song the warrior pupils circle the smoke in a clockwise direction and constantly emit the victory call of the warrior (Hayward, 1997, p. 275).

This latter is “Lha Gyelo — victory to the gods” — the same call which the Dalai Lama cried out as he crossed the Tibetan border on his flight in 1959.

Trungpa was even more fascinated by the ancient national hero, Gesar, whose barbaric daredevilry we have already sketched in detail, than he was by the dharmapalas. The guru recommended the atavistic war hero to his followers as an example to imitate. Time and again he proudly indicated that his family belonged to the belligerent nomadic tribe of the “Mukpo”, from whose ranks Gesar also came. For this reason he ennobled his pupils as the “Mukpo family” and thus proclaimed them to be comrades-in-arms of Gesar.

The latter — said Trungpa — would return from Shambhala,

“leading an army to conquer the forces of darkness in the world”.

(Trungpa, 1986, p. 7).

But Trungpa did not just summon up Tibetan dharmapalas and heroes with his magic, rather he also invoked the deceased spirits of an international, on closer examination extremely problematic, warrior caste: the Japanese samurai, the North American plains Indians, the Jewish King David, and the British King Arthur with his round table — all archetypal leading figures who believed that justice could only be achieved with a sword in the hand, who were all absolutely ruthless in creating peace.

These “holy warriors” always stood opposed to the “barbarians” of another religion who had to be exterminated.

The non-dualist world view which many of the original Buddhist texts so forcefully demand is completely cancelled out in the mythic histories of these warlike models.

Trungpa led his courses under the name of “Dorje Dradul” which means “invincible warrior”. Completely in accord with an atavistic fighter tradition only beasts of prey were accepted as totem animals for his pupils: the snow lion, the tiger, the dragon. Dorje Dradul was especially enthusiastic about the mythic sun bird, the garuda, about its fiery redness, wildness, and its piercing cry commanding the cessation of thought like a lightning bolt (Hayward, 197, p. 251).

Garuda is the sun bird par excellence, and since time immemorial the followers of the warrior caste have also been worshippers of the sun. Thus in the center of Trungpa’s Shambhala mission a solar cult is fostered. But it is not the natural sun which lights up all, but rather the “Great Eastern Sun” which rises at the beginning of a new world era when the Shambhala warriors seize power over the world.

It sinks as a mighty cult symbol into the hearts of his pupils:

“So, we begin to appreciate the Great Eastern Sun, not as something outside from us, like the sun in the sky, but as the Great Eastern Sun in our head and shoulders, in our face, our hair, our lips, our chest”

(Trungpa, 1986, p. 39).

Why of all people it was the chairman of the Communist Party of China, Mao Zedong, who was worshipped by the Red Guard as the Great Eastern Sun is a topic to which we shall return.

The basic ideology of the Shambhala program divides the world into two visions: Great Eastern Sun, which corresponds to enlightenment in the Buddhist path, and setting sun, which corresponds to samsara. [...]

Great Eastern Sun is cheering up; setting sun is complaining and criticizing. Great Eastern sun ist elegant und rich; setting sun is sloppy and poor. To paraphrase George Orwell:

“Great Eastern Sun good, setting sun bad.” (Butterfield, 1994, p. 96)